Cornish dialect

The Cornish dialect (also known as Cornish English, Cornu-English, Cornish: Sowsnek Kernowek) is a dialect of English spoken in Cornwall by Cornish people. Dialectal English spoken in Cornwall is to some extent influenced by Cornish grammar, and often includes words derived from the Cornish language. The Cornish language is a Celtic language of the Brythonic branch, as are the Welsh and Breton languages. In addition to the distinctive words and grammar, there are a variety of accents found within Cornwall from the north coast to that of the south coast and from east to west Cornwall. Typically, the accent is more divergent from Standard British English the further west through Cornwall one travels. The speech of the various parishes being to some extent different from the others was described by John T. Tregellas and Thomas Q. Couch towards the end of the 19th century. Tregellas wrote of the differences as he understood them and Couch suggested the parliamentary constituency boundary between the East and West constituencies, from Crantock to Veryan, as roughly the border between eastern and western dialects. To this day, the towns of Bodmin and Lostwithiel as well as Bodmin Moor are considered the boundary.[1][2][3]

| Cornish English, Cornish dialect | |

|---|---|

| Native to | United Kingdom |

| Region | Cornwall |

Indo-European

| |

Early forms | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | None |

| IETF | en-cornu |

History

The first speakers of English resident in Cornwall were Anglo-Saxon settlers, primarily in the north east of Cornwall between the Ottery and Tamar rivers, and in the lower Tamar valley, from around the 10th century onwards. There are a number of relatively early place names of English origin, especially in those areas.[4]

The further spread of the English language in Cornwall was slowed by the change to Norman French as the main language of administration after the Norman Conquest. In addition, continued communication with Brittany, where the closely related Breton language was spoken, tended to favour the continued use of the Cornish language.

But from around the 13th to 14th centuries the use of English for administration was revived, and a vernacular Middle English literary tradition developed. These were probable reasons for the increased use of the English language in Cornwall.[5] In the Tudor period, various circumstances, including the imposition of an English language prayer book in 1549, and the lack of a Cornish translation of any part of the Bible, led to a language shift from Cornish to English.

The language shift to English occurred much later in Cornwall than in other areas: in most of Devon and beyond, the Celtic language had probably died out before the Norman Conquest.[6] However the Celtic language survived much later in the westernmost areas of Cornwall, where there were still speakers as late as the 18th century.[7] For this reason, there are important differences between the Anglo-Cornish dialect and other West Country dialects.

Cornish was the most widely spoken language west of the River Tamar until around the mid-14th century, when Middle English began to be adopted as a common language of the Cornish people.[8] As late as 1542 Andrew Boorde, an English traveller, physician and writer, wrote that in Cornwall were two languages, "Cornysshe" and "Englysshe", but that "there may be many men and women" in Cornwall who could not understand English".[9] Since the Norman language was the mother tongue of most of the English aristocracy, Cornish was used as a lingua franca, particularly in the far west of Cornwall.[10] Many Cornish landed gentry chose mottos in the Cornish language for their coats of arms, highlighting its high social status.[11] The Carminow family used the motto "Cala rag whethlow", for example.[12] However, in 1549 and following the English Reformation, King Edward VI of England commanded that the Book of Common Prayer, an Anglican liturgical text in the English language, should be introduced to all churches in his kingdom, meaning that Latin and Celtic customs and services should be discontinued.[8] The Prayer Book Rebellion was a militant revolt in Cornwall and parts of neighbouring Devon against the Act of Uniformity 1549, which outlawed all languages from church services apart from English,[13] and is cited as a testament to the affection and loyalty the Cornish people held for the Cornish language.[11] In the rebellion, separate risings occurred simultaneously at Bodmin in Cornwall, and Sampford Courtenay in Devon—which would converge at Exeter, laying siege to the region's largest Protestant city.[14] However, the rebellion was suppressed, due largely to the aid of foreign mercenaries, in a series of battles in which "hundreds were killed",[15] effectively ending Cornish as the common language of the Cornish people.[9] The Anglicanism of the Reformation served as a vehicle for Anglicisation in Cornwall; Protestantism had a lasting cultural effect upon the Cornish by way of linking Cornwall more closely with England, while lessening political and linguistic ties with the Bretons of Brittany.[16]

The English Civil War, a series of armed conflicts and political machinations between Parliamentarians and Royalists, polarised the populations of England and Wales. However, Cornwall in the English Civil War was a staunchly Royalist enclave, an "important focus of support for the Royalist cause".[17] Cornish soldiers were used as scouts and spies during the war, for their language was not understood by English Parliamentarians.[17] Following the war there was a further shift to the English language by the Cornish people, which encouraged an influx of English people to Cornwall. By the mid-17th century the use of Cornish had retreated far enough west to prompt concern and investigation by antiquarians, such as William Scawen who had been an officer during the Civil War.[16][17] As the Cornish language diminished, the people of Cornwall underwent a process of English enculturation and assimilation,[18] becoming "absorbed into the mainstream of English life".[19]

International use

Large-scale 19th and 20th century emigrations of Cornish people meant that substantial populations of Anglo-Cornish speakers were established in parts of North America, Australia, and South Africa. This Cornish diaspora has continued to use Anglo-Cornish, and certain phrases and terms have moved into common parlance in some of those countries.

There has been discussion over whether certain words found in North America have an origin in the Cornish language, mediated through Anglo-Cornish dialect.[20] Legends of the Fall, a novella by American author Jim Harrison, detailing the lives of a Cornish American family in the early 20th century, contains several Cornish language terms. These were also included in the Academy Award-winning film of the same name starring Anthony Hopkins as Col. William Ludlow and Brad Pitt as Tristan Ludlow. Some words in American Cornu-English are almost identical to those in Anglo-Cornish:[21]

| American Cornu-English | Cornish | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| Attle | Atal | Waste |

| Bal | Bal | Mine |

| Buddle | Buddle | Washing pit for ore, churn |

| Cann | Cand | White spar stone |

| Capel | Capel | Black tourmaline |

| Costean | Costeena | To dig exploratory pits |

| Dippa | Dippa | A small pit |

| Druse | Druse | Small cavity in a vein |

| Flookan | Flookan | Soft layer of material |

| Gad | Gad | Miner's wedge or spike |

| Yo | Yo | A derivative of 'You', a greeting or 'Hello' |

South Australian Aborigines, particularly the Nunga, are said to speak English with a Cornish accent because they were taught the English language by Cornish miners.[22][23] Most large towns in South Australia had newspapers at least partially in Cornish dialect: for instance, the Northern Star published in Kapunda in the 1860s carried material in dialect.[24][25][26] At least 23 Cornish words have made their way into Australian English; these include the mining terms fossick and nugget.[27]

Geography

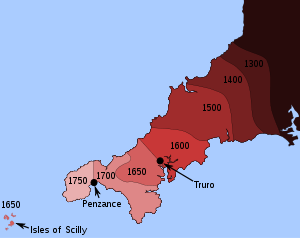

There is a difference between the form of Anglo-Cornish spoken in west Cornwall and that found in areas further east. In the eastern areas, the form of English that the formerly Cornish-speaking population learnt was the general south-western dialect, picked up primarily through relatively local trade and other communications over a long period of time. In contrast, in western areas, the language was learned from English as used by the clergy and landed classes, some of whom had been educated at the English universities of Oxford and Cambridge.[28] English was learned relatively late across the western half of Cornwall (see map above) and this was a more Modern English style of language, since the standard form itself was undergoing changes.[29] Particularly in the west, the Cornish language substrate left characteristic markers in the Anglo-Cornish dialect.

Phonologically, the lenition of f, s, th occurs in East Cornwall, as in the core West Country dialect area, but not in west Cornwall. The second person pronoun, you (and many other occurrences of the same vowel) is pronounced as in standard English in the west of Cornwall; but east of the Bodmin district, a 'sharpening' of the vowel occurs, which is a feature also found in Devon dialect. Plural nouns such as ha'pennies, pennies and ponies are pronounced in west Cornwall ending not in -eez but in -uz. The pronunciation of the number five varies from foive in the west to vive in the east, approaching the Devon pronunciation.[30] This challenges the commonly held misconception that the dialect is uniform across the county.

Variations in vocabulary also occur: for example the dialect word for ant in East Cornwall is emmet which is of Old English etymology, whereas in West Cornwall the word muryan is used. This is a word from the Cornish language spelt in the revived language (in Kernewek Kemmyn dictionaries) as muryon. There is also this pair, meaning the weakest pig of a litter: nestle-bird (sometimes nestle-drish) in East Cornwall, and (piggy-)whidden in West Cornwall. Whidden may derive from Cornish byghan (small), or gwynn (white, Late Cornish gwydn). Further, there is pajerpaw vs a four-legged emmet in West and mid-Cornwall respectively. It may be noted that the Cornish word for the number four is peswar (Late Cornish pajar). For both of these Cornish language etymologies, sound changes within the Cornish language itself between the Middle Cornish and Late Cornish periods are in evidence.

When calling a horse to stop "wo" is used in most of east Cornwall and in the far west; however "ho" is used between a line from Crantock to St Austell and a line from Hayle to the Helford River; and "way" is used in the northeast.[31]

There are also grammatical variations within Cornwall, such the use of us for the standard English we and her for she in East Cornwall, a feature shared with western Devon dialect.[32] I be and its negative I bain't are more common close to the Devon border.[30]

The variety of English in the Isles of Scilly is unlike that on the mainland as Bernard Walke observed in the 1930s. He found that Scillonians spoke English similar to "Elizabethan English without a suspicion of Cornish dialect".[33]

Lexicon and grammar

There are a range of dialect words including words also found in other West Country dialects, as well as many specific to Anglo-Cornish.[34][35][36]

There are also distinctive grammatical features:[30]

- reversals (e.g. Her aunt brought she up)

- archaisms (e.g. give 'un to me – 'un is a descendant of Old English hine)

- the retention of thou and ye (thee and ye ('ee)) – Why doesn't thee have a fringe?

- double plurals – clothes-line postes

- irregular use of the definite article – He died right in the Christmas

- use of the definite article with proper names – Did 'ee knaw th'old Canon Harris?

- the omission of prepositions – went chapel

- the extra -y suffix on the infinitive of verbs I ain't one to gardeny, but I do generally teal (till) the garden every spring

- they as a demonstrative adjective – they books

- use of auxiliary verb – pasties mother do make

- inanimate objects described as he

- frequent use of the word up as an adverb – answering up

- the use of some as an adverb of degree – She's some good maid to work

Many of these are influenced by the substrate of the Cornish language. One example is the usage for months, May month, rather than just May for the fifth month of the year.

Sociolinguistics

From the late 19th to the early 21st century, the Anglo-Cornish dialect declined somewhat due to the spread of long-distance travel, mass education and the mass media, and increased migration into Cornwall of people from, principally, the south-east of England. Universal elementary education had begun in England and Wales in the 1870s. Thirty years later Mark Guy Pearse wrote: "The characteristics of Cornwall and the Cornish are rapidly passing away. More than a hundred years ago its language died. Now its dialect is dying. It is useless to deplore it, for it is inevitable."[37] Although the erosion of dialect is popularly blamed on the mass media, many academics assert the primacy of face-to-face linguistic contact in dialect levelling.[38] It is further asserted by some that peer groups are the primary mechanism.[39] It is unclear whether in the erosion of the Anglo-Cornish dialect, high levels of migration into Cornwall from outside in the 20th century, or deliberate efforts to suppress dialect forms (in an educational context) are the primary causative factor. Anglo-Cornish dialect speakers are more likely than Received Pronunciation speakers in Cornwall to experience social and economic disadvantages and poverty, including spiralling housing costs, in many, particularly coastal areas of Cornwall,[40] and have at times been actively discouraged from using the dialect, particularly in the schools.[41][42] In the 1910s the headmaster of a school in a Cornish fishing port received this answer when he suggested to the son of the local coastguard (a boy with rough and ready Cornish speech) that it was time he learned to speak properly: "An what d'yer think me mates down to the quay 'ud think o' me if I did?"[43]

A. L. Rowse wrote in his autobiographical A Cornish Childhood about his experiences of a Received Pronunciation prestige variety of English (here referred to as the "King's English") being associated with well-educated people, and therefore Anglo-Cornish by implication with a lack of education:

'It does arise directly from the consideration of the struggle to get away from speaking Cornish dialect and to speak correct English, a struggle which I began thus early and pursued constantly with no regret, for was it not the key which unlocked the door to all that lay beyond—Oxford, the world of letters, the community of all who speak the King's English, from which I should otherwise have been infallibly barred? But the struggle made me very sensitive about language; I hated to be corrected; nothing is more humiliating: and it left me with a complex about Cornish dialect. The inhibition which I had imposed on myself left me, by the time I got to Oxford, incapable of speaking it; and for years, with the censor operating subconsciously ... '[44]

Preservation

Once it was noticed that many aspects of Cornish dialect were gradually passing out of use, various individuals and organisations (including the Federation of Old Cornwall Societies)[45] began to make efforts to preserve the dialect. This included collecting lists of dialect words, although grammatical features were not always well recorded. Nevertheless, Ken Phillipps's 1993 Glossary of the Cornish Dialect[30] is an accessible reference work which does include details of grammar and phonology. A more popular guide to Cornish dialect has been written by Les Merton, titled Oall Rite Me Ansum![46]

Another project to record examples of Cornish dialect[47] is being undertaken by Azook Community Interest Company. As of 2011 it has received coverage in the local news[48] and more information on the project should one hopes be uploaded dreckly.

Literature

There have been a number of literary works published in Anglo-Cornish dialect from the 19th century onwards.

- John Tabois Tregellas (1792–1863) was a merchant at Truro, purser of Cornish mines, and author of many stories written in the local dialect of the county. (Walter Hawken Tregellas was his eldest son.)[49][50][51][52] Tregellas was well known in Cornwall for his dialect knowledge; he could relate a conversation between a Redruth man and a St Agnes man keeping their dialects perfectly distinct.[53]

- William Robert Hicks (known as the "Yorick of the West") was an accomplished raconteur. Many of his narratives were in the Cornish dialect, but he was equally good in that of Devon, as well as in the peculiar talk of the miners. Among his best-known stories were the "Coach Wheel", the "Rheumatic Old Woman", "William Rabley", the "Two Deacons", the "Bed of Saltram", the "Blind Man, his Wife, and his dog Lion", the "Gallant Volunteer", and the "Dead March in Saul". His most famous story, the "Jury", referred to the trial at Launceston in 1817 of Robert Sawle Donnall for poisoning his mother-in-law, when the prisoner was acquitted. Each of the jurors gave a different and ludicrous reason for his verdict.[54]

_(14753162795).jpg)

- There is a range of dialect literature dating back to the 19th century referenced in Bernard Deacon's PhD thesis.[55]

- 'The Cledry Plays; drolls of old Cornwall for village acting and home reading' (Robert Morton Nance (Mordon), 1956).[56] In his own words from the preface: these plays were "aimed at carrying on the West-Penwith tradition of turning local folk tales into plays for Christmas acting. What they took over from these guise-dance drolls, as they were called, was their love of the local speech and their readiness to break here and there into rhyme or song". And of the music he says "the simple airs do not ask for accompaniment or for trained voices to do them justice. They are only a slight extension of the music that West-Penwith voices will put into the dialogue."

- Cornish Dialect Stories: About Boy Willie (H. Lean, 1953)[57]

- Pasties and Cream: a Proper Cornish Mixture (Molly Bartlett (Scryfer Ranyeth), 1970): a collection of Anglo-Cornish dialect stories that had won competitions organised by the Cornish Gorsedh.[58]

- Cornish Faist: a selection of prize winning dialect prose and verse from the Gorsedd of Cornwall Competitions.[59]

- Various literary works by Alan M. Kent, Nick Darke and Craig Weatherhill

See also

- List of Cornish dialect words

- Regional accents of English speakers

- Gallo (Brittany)

- Lowland Scots

Other English dialects heavily influenced by Celtic languages:

- Anglo-Manx

- Bungi creole

- Hiberno-English

- Highland English (and Scottish English)

- Welsh English

References

- Perry, Margaret. "Cornish Dialect and Language: a potted history". Newlyn.info. Archived from the original on 29 September 2011. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- "Old Cornwall Society Dialect Webpages". Federation of Old Cornwall Societies (Cornwall, United Kingdom). Archived from the original on 22 June 2011. Retrieved 16 June 2011.

- Couch, Thomas Q. "East Cornwall Words". Federation of Old Cornwall Societies (Cornwall, United Kingdom). Archived from the original on 7 August 2011. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

- Wakelin, Martyn Francis (1975). Language and History in Cornwall. Leicester: Leicester University Press. p. 55. ISBN 0-7185-1124-7.

- Ousby, Ian (1993). The Cambridge Guide to Literature in English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 302. ISBN 978-0-521-44086-8.

- Jackson, Kenneth (1953). Language and History in Early Britain: a chronological survey of the Brittonic languages. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 1-85182-140-6.

- Spriggs, Matthew (2003). "Where Cornish was spoken and when: a provisional synthesis". Cornish Studies. Second Series (11): 228–269. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 16 June 2011.

- "Overview of Cornish History". Cornwall Council. 23 June 2009. Retrieved 3 July 2009.

- "Timeline of Cornish History 1066–1700 AD". Cornwall Council. 10 June 2009. Retrieved 3 July 2009.

- Tanner, Marcus (2006), The Last of the Celts, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-11535-2; p. 225

- Tanner, Marcus (2006), The Last of the Celts, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-11535-2; p. 226

- Pascoe, W. H. (1979) A Cornish Armory. Padstow: Lodenek Press; p. 27

- Pittock, Murray (1999), Celtic Identity and the British Image, Manchester University Press, ISBN 978-0-7190-5826-4; p. 122

- Zagorín, Pérez (1982), Rebels and Rulers, 1500–1660: provincial rebellion; revolutionary civil wars, 1560–1660, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-28712-8; p. 26

- Magnaghi, Russell M. (2008), Cornish in Michigan, East Lansing: MSU Press, ISBN 978-0-87013-787-7; pp. 2–3

- Tanner, Marcus (2006), The Last of the Celts, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-11535-2; p. 230

- Price, Glanville (2000), Languages in Britain and Ireland, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-0-631-21581-3; p. 113

- Hechter, Michael (1999), Internal Colonialism: the Celtic fringe in British national development (2nd ed.), Transaction, ISBN 978-0-7658-0475-4; p. 64

- Stoyle, Mark (1 January 2001). "The Cornish: a Neglected Nation?". Bbc.co.uk. p. 1. Retrieved 4 July 2009.

- Kent, Alan (26–27 July 2007). ""Mozeying on down ..." : the Cornish language in North America". The Celtic Languages in Contact: papers from the workshop within the framework of the XIII International Congress of Celtic Studies.

- Hildegard L. C. Tristram (2007). The Celtic Languages in Contact: Papers from the Workshop Within the Framework of the XIII International Congress of Celtic Studies, Bonn, 26-27 July 2007. Universitätsverlag Potsdam. p. 204. ISBN 978-3-940793-07-2.

- Sutton, Peter (June 1989). "Postvocalic R in an Australian English Dialect". Australian Journal of Linguistics. 9 (1): 161–163. doi:10.1080/07268608908599416. Retrieved 16 June 2011.

- Leitner, Gerhard (2007). The Habitat of Australia's Aboriginal Languages. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. p. 170. ISBN 978-3-11-019079-3.

- Payton, Philip (2005). The Cornish Overseas: a history of Cornwall's 'great emigration'. Dundurn Press Ltd. p. 185. ISBN 1-904880-04-5.

- "Northern Star (Kapunda, S. Aust.)". State Library of South Australia, State Library of Victoria: National Library of Australia. Retrieved 16 June 2011.

- Stephen Adolphe Wurm; Peter Mühlhäusler & Darrell T. Tryon. Atlas of Languages of Intercultural Communication in the Pacific, Asia and the Americas. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1996

- Bruce Moore Speaking our Language: the story of Australian English, Oxford University Press, 2009

- These were the only universities in England (and not open to Nonconformists) until the 1820s, when University College London was established.

- Wakelin, Martyn Francis (1975). Language and History in Cornwall. Leicester: Leicester University Press. p. 100. ISBN 0-7185-1124-7.

- Phillipps, Ken C. (1993). A Glossary of the Cornish Dialect. Padstow, Cornwall: Tabb House. ISBN 0-907018-91-2.

- Upton, Clive; Widdowson, J. D. A. (1996). An Atlas of English Dialects. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 180–81.

- These pronouns are not the only ones, of course.

- Walke, Bernard Twenty Years at St Hilary. Mount Hawke: Truran, 2002 ISBN 9781850221647

- "Cornish Dialect Dictionary". Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- Fred Jago (1882). "The Ancient Language and the Dialect of Cornwall: with an enlarged glossary of Cornish provincial words; also an appendix, containing a list of writers on Cornish dialect, and additional information about Dolly Pentreath, the last known person who spoke the ancient Cornish as her mother tongue". Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- P. Stalmaszczyk. "Celtic Elements in English Vocabulary–a critical reassessment" (PDF). Studia Anglica Posnaniensia. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- Pearse, Mark Guy (1902) West Country Songs. London: Howard Marshall & Son; p. vii

- Kerswill, Paul. "Dialect levelling and geographical diffusion in British English" (PDF).

- Paul Kerswill and Peter Trudgill. "The birth of new dialects" (PDF). Macrosociolinguistic Motivations of Convergence and Divergence. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- Kent, Alan (2006). "Bringin’ the Dunkey Down from the Carn:" Cornu-English in Context 1549–2005 – A Provisional Analysis, in (PDF). Potsdam: Univ.-Verl. Potsdam. pp. 6–33. ISBN 3-939469-06-8.

- Schwartz, Sharron P. "Bridging" the Great Divide": Cornish Labour Migration to America and the Evolution of Transnational Identity" (PDF). Paper presented at the Race, Ethnicity and Migration: The United States in a Global Context Conference, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. Institute of Cornish Studies, University of Exeter, Hayne Corfe Centre, Truro, Cornwall, Great Britain. Retrieved 16 June 2011.

- Bremann, Rolf (1984). Soziolinguistische Untersuchungen zum Englisch von Cornwall. Frankfurt am Main: P. Lang. ISBN 3-8204-5171-4.

- Archer, Muriel F. "Sounding a bit fishy" [letter to the editor], The Guardian; 3 August 1982

- Rowse, A. L. (1942). A Cornish Childhood. London: Cape. p. 106.

- "Old Cornwall Society Dialect Webpages". Federation of Old Cornwall Societies (Cornwall, United Kingdom). Archived from the original on 22 June 2011. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- Merton, Les (2003). Oall Rite Me Ansom! a salute to the Cornish Dialect. Newbury: Countryside Books. ISBN 1-85306-814-4.

- "Website of Azook Community Interest Company, based in Pool, Cornwall". Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- "Plenty of tales with Cornish accent still to tell". West Briton (thisiscornwall.co.uk). Archived from the original on 5 April 2012. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- Dictionary of National Biography; ed. Leslie Stephen

- Tregellas, Walter Hawken (1884). Cornish Worthies: sketches of some eminent Cornish men and families. London: E. Stock.

- Tregellas, John Tabois (1890) [1868]. Cornish Tales in Prose and Verse. Truro: Netherton & Worth.

- Tregellas, John Tabois (1894) [1879]. Peeps into the Haunts and Homes of the Rural Population of Cornwall: being reminiscences of Cornish character & characteristics, illustrative of the dialect, peculiarities, &c., &c., of the inhabitants of west & north Cornwall. Truro: Netherton & Worth.

- Vyvyan, C. C. (1948) Our Cournwall. London: Westaway Books; p. 21

- Boase, G. C. (1891). "Hicks, William Robert (1808–1868), asylum superintendent and humorist". Dictionary of National Biography Vol. XXVI. Smith, Elder & Co. Retrieved 23 December 2007.

- Deacon, Bernard. "Research: Bernard Deacon – personal webpage at Institute of Cornish Studies". Archived from the original on 21 July 2009.

- Nance, Robert Morton (Mordon) (1956). The Cledry Plays; drolls of old Cornwall for village acting and home reading. Federation of Old Cornwall Societies (printed by Worden, Marazion).

- Lean, H. (1953). Cornish Dialect Stories – About Boy Willie. Falmouth, Cornwall: J. H. Lake & Co., Ltd.

- Bartlett, Molly (1970). Pasties and Cream: a proper Cornish mixture. Penzance, Cornwall: Headland Printing Company.

- James, Beryl (1979). 'Cornish Faist': a selection of prize winning dialect prose and verse from the Gorsedd of Cornwall Competitions. Redruth, Cornwall, UK: Dyllansow Truran. ISBN 0-9506431-3-0.

![]()

Further reading

- M. A. Courtney; T. Q. Couch: Glossary of Words in Use in Cornwall. West Cornwall, by M. A. Courtney; East Cornwall, by T. Q. Couch. London: published for the English Dialect Society, by Trübner & Co., 1880

- Pol Hodge: The Cornish Dialect and the Cornish Language. 19 p. Gwinear: Kesva an Taves Kernewek, 1997 ISBN 0-907064-58-2

- David J. North & Adam Sharpe: A Word-geography of Cornwall. Redruth: Institute of Cornish Studies, 1980 (includes word-maps of Cornish words)

- Martyn F. Wakelin: Language and History in Cornwall. Leicester University Press, 1975 ISBN 0-7185-1124-7 (based on the author's thesis, University of Leeds, 1969)