Falkland Islands English

Falkland Islands English is mainly British in character. However, as a result of the isolation of the islands, the small population has developed and retains its own accent/dialect, which persists despite many immigrants from the United Kingdom in recent years. In rural areas (i.e. anywhere outside Stanley), known as ‘Camp’ (from Spanish campo or ‘countryside’),[2] the Falkland accent tends to be stronger. The dialect has resemblances to Australian, New Zealand, West Country and Norfolk dialects of English, as well as Lowland Scots.

| Part of a series on |

| The English language |

|---|

| Topics |

|

| Advanced topics |

|

| Phonology |

| Dialects |

|

| Teaching |

Higher category: Language |

| Falkland Islands English | |

|---|---|

| Native to | United Kingdom |

| Region | Falkland Islands |

| Ethnicity | (presumably close to the ethnic population) |

Native speakers | 1,700 (2012 census)[1] |

Indo-European

| |

Early forms | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | None |

| IETF | en-FK |

Two notable Falkland Island terms are ‘kelper’ meaning a Falkland Islander, from the kelp surrounding the islands (sometimes used pejoratively in Argentina)[3] and ‘smoko’, for a smoking break (as in Australia and New Zealand).

The word ‘yomp’ was used by the British armed forces during the Falklands War but is passing out of usage.

In recent years, a substantial Saint Helenian population has arrived, mainly to do low-paid work, and they too have a distinct form of English.

Settlement history

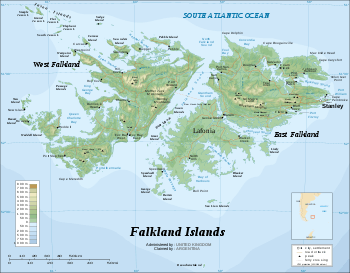

The Falkland Islands, a cluster of 780 islands off the eastern coast of Argentina, had no indigenous population when the British arrived to explore the islands in 1690.[4] Continuous settlement dates only to 1833, when British forces removed 26 Argentinian soldiers from the islands and claimed the islands for the British.[4] In 1845, the Capital city of Stanley, located on East Falkland, was established.[5] Argentina also has a claim to the islands, and in 1982, Argentine forces invaded the Falkland Islands. The British moved to defend the British control of the Islands, with Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher calling the Islanders "of British tradition and stock".[6] In under three months, nearly a thousand people were killed, and over 2,000 were injured.[7] British-Argentinian tension regarding claim to the Islands still exists, but as over 98% of Islanders voted to remain under British sovereignty in the last election, the identity of the island overall is overwhelmingly British.[8] This history has implications for the linguistic features of Falkland Islands English, which is similar to British English but distinct in some vocabulary and phonology.

Phonetics and phonology

English in the Falklands is non-rhotic.[9] This is consistent with other varieties of English in the southern hemisphere.[9] One major difference between the English of the Falklands and other Englishes of the southern hemisphere is the onset centralization of /ai/, in which nice is pronounced /nəɪs/.[9]

Vocabulary

The Falklands English vernacular has a fair number of borrowed Spanish words (often modified or corrupted). These include colloquialisms such as ‘che’, also encountered in Rioplatense Spanish from Argentina, and ‘poocha’ equivalent to ‘wow’.[10] or ‘damn’,[11] (from pucha, a euphemism for puta or ‘whore’).[12]

They are particularly numerous, indeed dominant in the local horse-related terminology. For instance, the Islanders use ‘alizan’, ‘colorao’, ‘negro’, ‘blanco’, ‘gotiao’, ‘picasso’, ‘sarco’, ‘rabincana’ etc. for certain horse colours and looks, or ‘bosal’, ‘cabresta’, ‘bastos’, ‘cinch’, ‘conjinilla’, ‘meletas’, ‘tientas’, ‘manares’ etc. for various items of horse gear.[13]

Unlike the older English, French and Spanish place names given by mariners, which refer mainly to islands, rocks, bays, coves, and capes (points), the post-1833 Spanish names usually identify inland geographical locations and features, reflecting the new practical necessity for orientation, land delimitation and management in the cattle and sheep farming. Among the typical such names or descriptive and generic parts of names are ‘Rincon Grande’, ‘Ceritos’, ‘Campito’, ‘Cantera’, ‘Terra Motas’, ‘Malo River’, ‘Brasse Mar’, ‘Dos Lomas’, ‘Torcida Point’, ‘Pioja Point’, ‘Estancia’, ‘Oroqueta’, ‘Piedra Sola’, ‘Laguna Seco’, ‘Manada’, etc.[13]

External links

References

- Falkland Islands Government - Census 2012: Statistics & Data Tables

- Stay with us » Camping: Falkland Islands Tourist Board

- ‘Second Class Citizens: The Argentine View of the Falkland Islanders’, P.J. Pepper, Falkland Islands Newsletter, November 1992

- Pereltsvang, Asya. "Falkland Islands English". Languages of the World. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- "Our History". Falkland Islands Government. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- BBC News http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/shared/spl/hi/guides/457000/457033/html/. Retrieved 24 March 2018. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Taylor, Alan. The Atlantic https://www.theatlantic.com/photo/2012/03/30-years-since-the-falklands-war/100272/. Retrieved 24 March 2018. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Tweedie, Neil (12 March 2013). "Falkland islands referendum: who were the three 'No' votes?". Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- Hickey, Raymond (2014). A Dictionary of Varieties of English (1 ed.). p. 119. doi:10.1002/9781118602607. ISBN 9781118602607.

- Are there places more British than the UK?, BBC News, 8 March 2013

- Concise Oxford Spanish Dictionary: Spanish-English/English-Spanish

- El gaucho Martín Fierro, José Hernández Editorial Pampa, 1963, page 247

- Spruce, Joan. Corrals and Gauchos: Some of the people and places involved in the cattle industry. Falklands Conservation Publication. Bangor: Peregrine Publishing, 1992. 48 pp.

Countries.png)