Durban

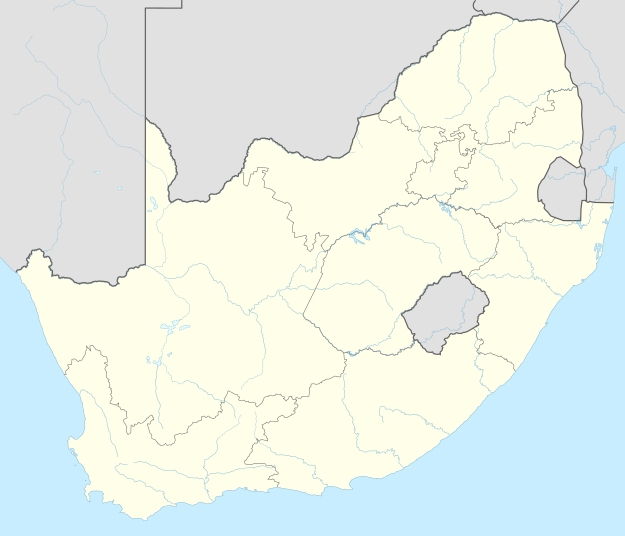

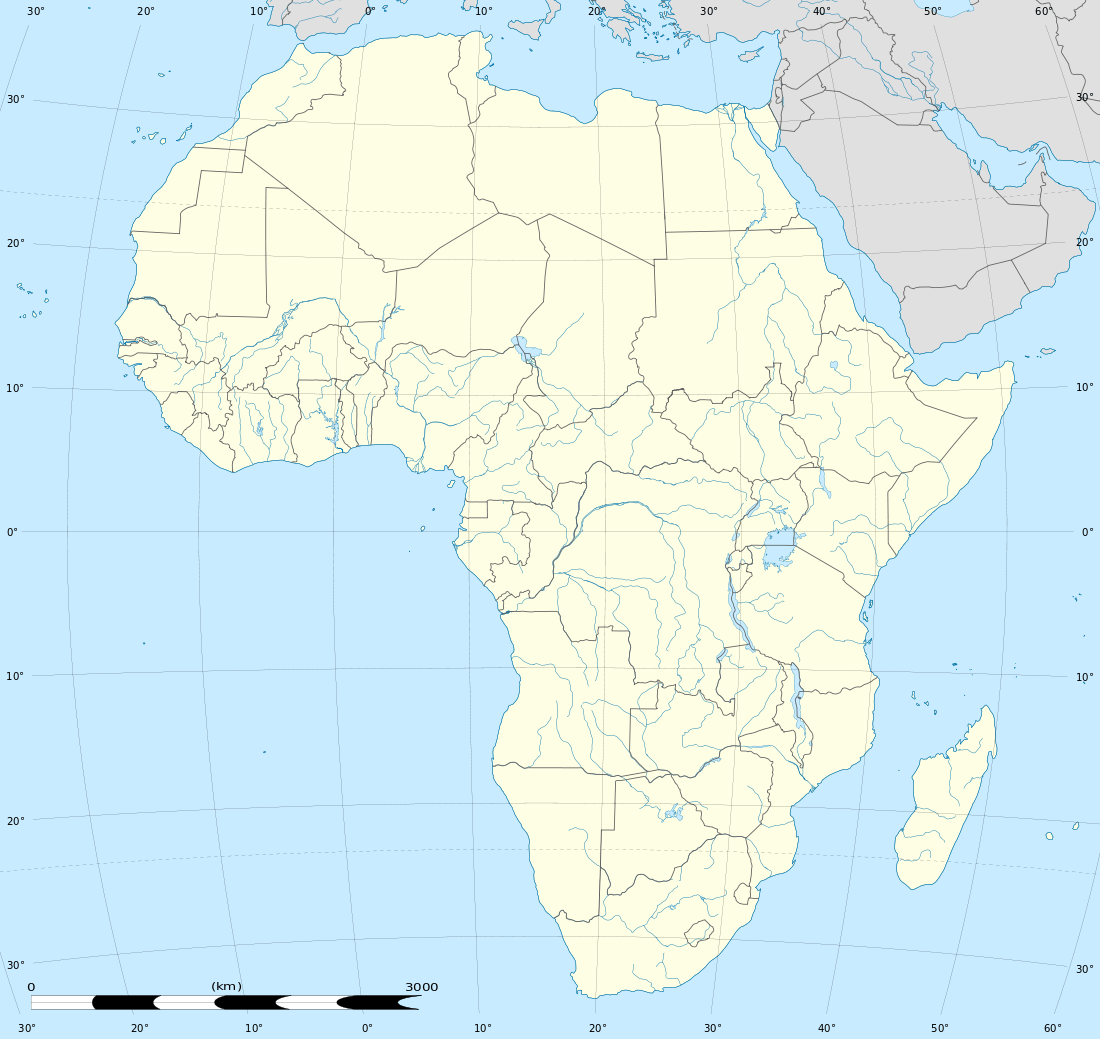

Durban (Zulu: eThekwini, from itheku meaning 'city') is the third most populous city in South Africa after Johannesburg and Cape Town and the largest city in the South African province of KwaZulu-Natal. Durban forms part of the eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality, which includes neighboring towns and has a population of about 3.44 million,[7] making the combined municipality one of the biggest cities on the Indian Ocean coast of the African continent.

Durban eThekwini | |

|---|---|

Clockwise from top left: Durban CBD, Ushaka Marine World, Suncoast Casino and Entertainment World, Moses Mabhida Stadium, Inkosi Albert Luthuli International Convention Centre and Durban City Hall. | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

Durban  Durban  Durban | |

| Coordinates: 29°53′S 31°03′E | |

| Country | |

| Province | KwaZulu-Natal |

| Municipality | eThekwini |

| Established | 1880[1][2] |

| Named for | Benjamin D'Urban |

| Government | |

| • Type | Metropolitan municipality |

| • Mayor | Mxolisi Kaunda (ANC) |

| Area | |

| • City | 225.91 km2 (87.22 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 2,292 km2 (885 sq mi) |

| Population (2018)[3] | |

| • City | 3,720,953 |

| • Density | 16,000/km2 (43,000/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 3,442,361 |

| • Metro density | 1,500/km2 (3,900/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Durbanite[5] |

| Racial makeup (2011) | |

| • Black African | 51.1% |

| • Coloured | 8.6% |

| • Indian/Asian | 24.0% |

| • White | 15.3% |

| • Other | 0.9% |

| First languages (2011) | |

| • English | 49.8% |

| • Zulu | 33.1% |

| • Xhosa | 5.9% |

| • Afrikaans | 3.6% |

| • Other | 7.6% |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (SAST) |

| Postal code (street) | 4001 |

| PO box | 4000 |

| Area code | 031 |

| GDP | US$ 83.9 billion[6] |

| GDP per capita | US$ 15,575[6] |

| Website | www |

History

Archaeological evidence from the Drakensberg mountains suggests that the Durban area has been inhabited by communities of hunter-gatherers since 100,000 BC. These people lived throughout the area of present-day KwaZulu-Natal until the expansion of Bantu farmers and pastoralists from the north saw their gradual displacement, incorporation or extermination. Little is known of the history of the first residents, as there is no written history of the area until it was sighted by Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama, who sailed parallel to the KwaZulu-Natal coast at Christmastide in 1497 while searching for a route from Europe to India. He named the area "Natal", or Christmas in Portuguese.[8]

Abambo People

In 1686 a ship from the Dutch East India Company named 'Stavenisse' wrecked off the eastern coast of South Africa. Some of the survivors made their way to the Bay of Natal (Durban) where they were taken in by Abambo tribe under leadership of Chief Langalibale. The crew became fluent in the language of the tribe and witnessed their customs. They told that the land where the Abambo people lived was called Embo by the natives and that the people were very hospitable. On the 28th of October 1689 the galiot 'Noord' traveled from Table Bay to the Bay of Natal for the purpose to fetch the survivors of the crew and to negotiate a deal to purchase the bay. The Noord arrived on the 9th of December 1689 where after the Dutch Cape Colony purchased the Bay of Natal from the Abambo people for £1650. A formal contract was drawn up by Laurens van Swaanswyk and signed by the Chief of the Abambo people, the crew of the Stavenisse acted as translators.[9]

First European settlers

In 1822 Lieutenant James King, captain of the ship Salisbury, together with Lt. Francis George Farewell, both ex-Royal Navy officers from the Napoleonic Wars, were engaged in trade between the Cape and Delagoa Bay. On a return trip to the Cape in 1823, they were caught in a very bad storm and decided to risk the Bar and anchor in the Bay of Natal. The crossing went off well and they found safe anchor from the storm. Lt. King decided to map the Bay and named the "Salisbury and Farewell Islands". In 1824 Lt. Farewell, together with a trading company called J. R. Thompson & Co., decided to open trade relations with Shaka the Zulu King and establish a trading station at the Bay. Henry Francis Fynn, another trader at Delagoa Bay, was also involved in this venture. Fynn left Delagoa Bay and sailed for the Bay of Natal on the brig Julia, while Farewell followed six weeks later on the Antelope. Between them they had 26 possible settlers, but only 18 stayed. On a visit to King Shaka, Henry Francis Fynn was able to befriend the King by helping him recover from a stab wound suffered as a result of an assassination attempt by one of his half-brothers. As a token of Shaka's gratitude, he granted Fynn a “25-mile strip of coast a hundred miles in depth.” On 7 August 1824 they concluded negotiations with King Shaka for a cession of land, including the Bay of Natal and land extending ten miles south of the Bay, twenty-five miles north of the Bay and one hundred miles inland. Farewell took possession of this grant and raised the Union Jack with a Royal Salute, which consisted of 4 cannon shots and twenty musket shots. Of the original 18 would-be settlers, only 6 remained, and they can be regarded as the founding members of Port Natal as a British colony. These 6 were joined by Lt. James Saunders King and Nathaniel Isaacs in 1825.

The modern city of Durban thus dates from 1824 when the settlement was established on the northern shores of the bay near today's Farewell Square.[10]

During a meeting of 35 European residents in Fynn's territory on 23 June 1835, it was decided to build a capital town and name it "D'Urban" after Sir Benjamin D'Urban, then governor of the Cape Colony.[11]

Republic of Natalia

The Voortrekkers established the Republic of Natalia in 1839, with its capital at Pietermaritzburg.

Tension between the Voortrekkers and the Zulus prompted the governor of the Cape Colony to dispatch a force under Captain Charlton Smith to establish British rule in Natal, for fear of losing British control in Port Natal. The force arrived on 4 May 1842 and built a fortification that was later to be The Old Fort. On the night of 23/24 May 1842 the British attacked the Voortrekker camp at Congella. The attack failed, and the British had to withdraw to their camp which was put under siege. A local trader Dick King and his servant Ndongeni were able to escape the blockade and rode to Grahamstown, a distance of 600 km (370 mi) in fourteen days to raise reinforcements. The reinforcements arrived in Durban 20 days later; the Voortrekkers retreated, and the siege was lifted.[12]

Fierce conflict with the Zulu population led to the evacuation of Durban, and eventually the Afrikaners accepted British annexation in 1844 under military pressure.

Durban's historic regalia

When the Borough of Durban was proclaimed in 1854, the council had to procure a seal for official documents. The seal was produced in 1855 and was replaced in 1882. The new seal contained a coat of arms without helmet or mantling that combined the coats of arms of Sir Benjamin D’Urban and Sir Benjamin Pine. An application was made to register the coat of arms with the College of Arms in 1906, but this application was rejected on grounds that the design implied that D’Urban and Pine were husband and wife. Nevertheless, the coat of arms appeared on the council's stationery from about 1912. The following year, a helmet and mantling was added to the council's stationery and to the new city seal that was made in 1936. The motto reads "Debile principium melior fortuna sequitur"—"Better fortune follows a humble beginning".

The blazon of the arms registered by the South African Bureau of Heraldry and granted to Durban on 9 February 1979. The coat of arms fell into disuse with the re-organisation of the South African local government structure in 2000. The seal ceased to be used in 1995.[13][14]

Government

With the end of apartheid, Durban was subject to restructuring of local government. The eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality was formed in 1994 after South Africa's first multiracial elections, with its first mayor being Sipho Ngwenya. The mayor is elected for a five-year term; however Sipho Ngwenya only served two years. In 1996, the city became part of the Durban UniCity in July 1996 as part of transitional arrangements and to eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality in 1999, with the adoption of South Africa's new municipal governance system. In July 1996, Obed Mlaba was appointed mayor of Durban UniCity; in 1999 he was elected to mayor of the eThekwini municipality and re-elected in 2006. Following the May 2011 local elections, James Nxumalo, the former Speaker of the Council, was elected as the new mayor. On 23 August 2016 Zandile Gumede was elected as the new mayor until the 13 August 2019.[15] On 5 September 2019 Mxolisi Kaunda was sworn in as the new mayor.[16]

The name of the Durban municipal government, prior to the post-apartheid reorganisations of municipalities, was the Durban Corporation or City of Durban.[17]

Geography

Durban is located on the east coast of South Africa, looking out upon the Indian Ocean. The city lies at the mouth of the Umgeni River, which demarcates parts of Durban's north city limit, while other sections of the river flow through the city itself. Durban has a natural harbour, Durban Harbour, which is the busiest port in South Africa and is the 4th-busiest in the Southern Hemisphere.

Climate

Durban has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen climate classification Cfa), with hot and humid summers and pleasantly warm and dry winters, which are snow and frost-free. Durban has an annual rainfall of 1,009 millimetres (39.7 in). The average temperature in summer ranges around 24 °C (75 °F), while in winter the average temperature is 17 °C (63 °F).

| Climate data for Durban (2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 37 (99) |

44 (111) |

37 (99) |

35 (95) |

34 (93) |

33 (91) |

30 (86) |

37 (99) |

38 (100) |

40 (104) |

39 (102) |

41 (106) |

44 (111) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 32.5 (90.5) |

36.5 (97.7) |

32.5 (90.5) |

30.5 (86.9) |

29.5 (85.1) |

28 (82) |

26 (79) |

30.5 (86.9) |

31.5 (88.7) |

32.5 (90.5) |

32.5 (90.5) |

34 (93) |

36.5 (97.7) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 28 (82) |

29 (84) |

28 (82) |

26 (79) |

25 (77) |

23 (73) |

22 (72) |

24 (75) |

25 (77) |

25 (77) |

26 (79) |

27 (81) |

25.5 (77.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 24.5 (76.1) |

25 (77) |

24 (75) |

21.5 (70.7) |

19.5 (67.1) |

17 (63) |

16 (61) |

18.5 (65.3) |

20 (68) |

21 (70) |

22 (72) |

23.5 (74.3) |

20.5 (68.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 21 (70) |

21 (70) |

20 (68) |

17 (63) |

14 (57) |

11 (52) |

10 (50) |

13 (55) |

15 (59) |

17 (63) |

18 (64) |

20 (68) |

15.5 (59.9) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | 16.5 (61.7) |

16.5 (61.7) |

16.5 (61.7) |

13 (55) |

8.5 (47.3) |

6 (43) |

7 (45) |

8 (46) |

8.5 (47.3) |

12.5 (54.5) |

14 (57) |

14.5 (58.1) |

6 (43) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 12 (54) |

12 (54) |

13 (55) |

9 (48) |

3 (37) |

1 (34) |

4 (39) |

3 (37) |

2 (36) |

8 (46) |

10 (50) |

9 (48) |

1 (34) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 134 (5.3) |

113 (4.4) |

120 (4.7) |

73 (2.9) |

59 (2.3) |

38 (1.5) |

39 (1.5) |

62 (2.4) |

73 (2.9) |

98 (3.9) |

108 (4.3) |

102 (4.0) |

1,019 (40.1) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 15.2 | 12.9 | 12.6 | 9.2 | 6.8 | 4.5 | 4.9 | 7.1 | 11.0 | 15.1 | 16.0 | 15.0 | 130.3 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 80 | 80 | 80 | 78 | 76 | 72 | 72 | 75 | 77 | 78 | 79 | 79 | 77 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 184.0 | 178.8 | 201.6 | 206.4 | 223.6 | 224.9 | 230.4 | 217.0 | 173.3 | 169.4 | 166.1 | 189.9 | 2,365.4 |

| Source 1: World Meteorological Organization[18] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA (sun, extremes and humidity)[19] | |||||||||||||

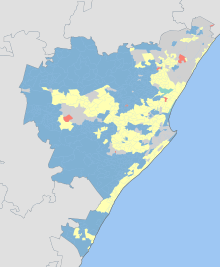

Demographics

Durban is ethnically diverse, with a cultural richness of mixed beliefs and traditions. Zulus form the largest single ethnic group. It has a large number of people of British and Indian descent. The influence of Indians in Durban has been significant, bringing with them a variety of cuisine, culture and religion.[20]

In the years following the end of Apartheid there was a population boom as Africans were allowed to move into the city. The population grew by 2.34% between 1996 and 2001. This led to shanty towns forming around the city which were often demolished. Between 2001 and 2011 the population growth slowed down to 1.08% per year and shanty towns have become less common as the government builds low-income housing.[21]

The population of the city of Durban and central suburbs such as Durban North, Durban South and the Berea increased 10.9% between 2001 and 2011 from 536,644 to 595,061.[22][23] The proportion of Black Africans increased while the proportion of people in all the other racial groups decreased. Black Africans increased from 34.9% to 51.1%. Indian or Asians decreased from 27.3% to 24.0%. Whites decreased from 25.5% to 15.3%. Coloureds decreased from 10.26% to 8.59%. A new racial group, Other, was included in the 2011 census at 0.93%.

The city's demographics indicate that 68% of the population are of working age, and 38% of the people in Durban are under the age of 19 years.[24]

It has the highest number of dollar millionaires added per year of any South African city with the number having increased 200 percent between 2000 and 2014.[25]

Economy

Informal sector

Durban has a number of informal and semi-formal street vendors. The Warwick Junction Precinct is home to a number of street markets, with vendors selling goods from traditional medicine, to clothing and spices.[26]

The city's treatment of shack dwellers was criticised in a report from the United Nations linked Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions[27] and there has also been criticism of the city's treatment of street traders,[28][29] street children[30] and sex workers.[31] The cannabis strain called 'Durban Poison' is named for the city.[32]

Civil society

There are a number of civil society organisations based in Durban. These include: Abahlali baseMjondolo (shack-dwellers') movement,[33] the Diakonia Council of Churches, the Right2Know Campaign, the South Durban Community Environmental Alliance and the South African Unemployed Peoples' Movement.[34][35][36][37][38][39] The Durban Art Gallery was founded in 1892.

Tourism

Durban has been named the greenest city in the world by Husqvarna Urban Green Space Index.[40][41]

- Burman Bush

- Durban Botanic Gardens

- Hawaan Forest[42]

- New Germany Nature Reserve[43]

- Pigeon Valley Nature reserve[44]

- Umgeni River Bird Park

- Umhlanga Lagoon Nature Reserve

- Kenneth Stainbank Nature Reserve

- Mitchell Park Zoo[45]

- Moses Mabhida Stadium. Activities include a Skycar ride or Adventure Walk to the top of the arch with 360 degree views over Durban; Guinness world record Bungee swing; Segway gliding tours of the stadium; Cafes and Restaurants; Monthly I Heart Durban market;

- Kingsmead Cricket Ground is a major test match and one-day cricket venue.

- Kings Park Stadium is host to the internationally renowned Sharks Rugby Team.

- Greyville Racecourse (home of the Durban July Handicap) and Durban Country Club and golf course.

- Durban Ice Arena Activities include leisure ice skating, birthday parties, school excursions, sporting events, teambuilding activities, corporate functions and group bookings.

Media

Two major English-language daily newspapers are published in Durban, both part of the Independent Newspapers, the national group owned by Sekunjalo Investments. These are the morning editions of The Mercury and the afternoon Daily News. Like most news media in South Africa, they have seen declining circulations in recent years. Major Zulu language papers comprise Isolezwe (Independent Newspapers), UmAfrika and Ilanga. Independent Newspapers also publish Post, a newspaper aimed largely at the Indian community. A national Sunday paper, the Sunday Tribune is also published by Independent Newspapers as is the Independent on Saturday.

A major city initiative is the eZasegagasini Metro Gazette.[46]

The national broadcaster, the SABC, has regional offices in Durban and operates two major stations there. The Zulu language Ukhozi FM has a huge national listenership of over 6.67 million, which makes it the second largest radio station in the world. The SABC also operates Radio Lotus, which is aimed at South Africans of Indian origin. The other SABC national stations have smaller regional offices in Durban, as does TV for news links and sports broadcasts. A major English language radio station, East Coast Radio,[47] operates out of Durban and is owned by SA media giant Kagiso Media. There are a number of smaller stations which are independent, having been granted licences by ICASA, the national agency charged with the issue of broadcast licences.

Sport

Durban was initially successful in its bid to host the 2022 Commonwealth Games,[48] but needed to withdraw in March 2017 from the role of hosts, citing financial constraints.[49] Birmingham, England replaced Durban as the host city.

Durban is home to the Cell C Sharks, who compete in the domestic Currie Cup competition as well as in the international Super Rugby competition. The Sharks' home ground is the 56,000 capacity Kings Park Stadium, sometimes referred to as the Shark Tank.

The city is home to two clubs in the Premier Soccer League — AmaZulu, and Golden Arrows. AmaZulu play most of their home games at the Moses Mabhida Stadium. Golden Arrows play most of their home games at the King Zwelithini Stadium in the suburb of Umlazi, but sometimes play some of their matches at Moses Mabhida Stadium or Chatsworth Stadium. It is also a home to some teams tha are playing in the NFD such as Royal Eagles FC and Royal Kings

Durban is host to the KwaZulu-Natal cricket team, who play as the Dolphins when competing in the Sunfoil Series. Shaun Pollock, Jonty Rhodes, Lance Klusener, Barry Richards, Andrew Hudson, Hashim Amla, Vince van der Bijl, Kevin Pietersen, Dale Benkenstein and David Miller are all players or past players of the Natal cricket team. International cricketers representing them include Malcolm Marshall, Dwayne Bravo and Graham Onions. Cricket in Durban is played at Kingsmead cricket ground.

Durban hosted matches in the 2003 ICC Cricket World Cup. In 2007 the city hosted nine matches, including a semi-final, as part of the inaugural ICC World Twenty20. The 2009 IPL season was played in South Africa, and Durban was selected as a venue. 2010 saw the city host six matches, including a semi-final, in the 2010 Champions League Twenty20.

Durban was one of the host cities of the 2010 FIFA World Cup, and A1GP held a race on a street circuit in Durban from 2006–2008. Durban hosted the 123rd IOC Session in July 2011.

The city is home to Greyville Racecourse, a major Thoroughbred horse racing venue which annually hosts a number of prestigious races including the country's premier event, the July Handicap, and the premier staying event in South Africa, the Gold Cup. Clairwood racecourse, south of the city, was a popular racing venue for many years, but was sold by the KZN racing authority in 2012.[50][51]

Durban hosts many famous endurance sports events annually, such as the Comrades Marathon, Dusi Canoe Marathon and the Ironman 70.3.

Transport

Air

King Shaka International Airport services both domestic and international flights, with regularly scheduled services to London, Dubai, Istanbul, Doha, Mauritius, Lusaka, Windhoek and Gaborone, as well as eight domestic destinations. The airport's position forms part of the Golden Triangle between Johannesburg and Cape Town, which is important for convenient travel and trade between these three major South African cities. The airport opened in May 2010. King Shaka International Airport handled 6.1 million passengers in 2019/2020, up 1.8 percent from 2018/2019. King Shaka International was constructed at La Mercy, about 36 kilometres (22 mi) north of central Durban. All operations at Durban International Airport have been transferred to King Shaka International as of 1 May 2010, with plans for flights to Singapore, Mumbai, Kigali, Luanda, Lilongwe and Nairobi.

Sea

Durban has a long tradition as a port city. The Port of Durban, formerly known as the Port of Natal, is one of the few natural harbours between Port Elizabeth and Maputo, and is also located at the beginning of a particular weather phenomenon which can cause extremely violent seas. These two features made Durban an extremely busy port of call for ship repairs when the port was opened in the 1840s.

MSC Cruises bases one of their cruise ships in Durban from November to April every year. From the 2019/2020 Southern Africa cruise season MSC Cruises will be basing the MSC Orchestra in Durban.[52] Durban is the most popular cruise hub in Southern Africa. Cruise destinations from Durban on the MSC Orchestra include Mozambique, Mauritius, Réunion, Madagascar and other domestic destinations such as Port Elizabeth and Cape Town. For the 2020/2021 cruise season MSC Cruises will be sending 2 ships being the MSC Musica & MSC Opera which will include additional cruise dates and Seychelles being added as a new cruise destination. [53] Many other ships cruise through Durban every year, including some of the world's biggest, such as the RMS Queen Mary 2, the biggest ocean liner in the world. Durban will be building a brand new R200 million cruise terminal that will be operational in October 2019, the Durban Cruise Terminal. The tender was awarded to KwaZulu Cruise Terminal (Pty) Ltd which is 70% owned by MSC Cruises SA and 30% by Africa Armada Consortium. The new cruise terminal will be able to accommodate two cruise ships at any given time.[54]

Naval Base Durban on Salisbury Island (now joined to the mainland and part of the Port of Durban), was established as a naval base during the Second World War. It was downgraded in 2002 to a naval station. In 2012 a decision was made to renovate and expand the facilities back up to a full naval base to accommodate the South African Navy's offshore patrol flotilla.[55] In December 2015 it was redesignated Naval Base Durban.[56]

Rail

Durban featured the first operating steam railway in South Africa when the Natal Railway Company started operating a line between the Point and the city of Durban in 1860.[57]

Shosholoza Meyl, the passenger rail service of Spoornet, operates two long-distance passenger rail services from Durban: a daily service to and from Johannesburg via Pietermaritzburg and Newcastle, and a weekly service to and from Cape Town via Kimberley and Bloemfontein. These trains terminate at Durban railway station.

Metrorail operates a commuter rail service in Durban and the surrounding area. The Metrorail network runs from Durban Station outwards as far as Stanger on the north coast, Kelso on the south coast, and Cato Ridge inland.

A high-speed rail link has been proposed, between Johannesburg and Durban.[58]

Roads

The city's main position as a port of entry onto the southern African continent has led to the development of national roads around it. The N3 Western Freeway, which links Durban with the economic hinterland of Gauteng, heads west out of the city. The N2 Outer Ring Road links Durban with the Eastern Cape to the south, and Mpumalanga in the north. The Western Freeway is particularly important because freight is shipped by truck to and from the Witwatersrand for transfer to the port.

The N3 Western Freeway starts in the central business district and heads west under Tollgate Bridge and through the suburbs of Sherwood and Mayville. The EB Cloete Interchange (which is informally nicknamed the Spaghetti Junction) lies to the east of Westville, allowing for transfer of traffic between the N2 Outer Ring Road and the Western Freeway.

The N2 Outer Ring Road cuts through the city from the north coast to the south coast. It provides a vital link to the coastal towns (such as Scottburgh and Stanger) that rely on Durban.

Durban also has a system of freeway and dual arterial metropolitan routes, which connect the sprawling suburbs that lie to the north, west and south of the city. The M4 exists in two segments. The northern segment, named the Ruth First Highway, starts as an alternative highway at Ballito where it separates from the N2. It passes through the northern suburbs of Umhlanga and La Lucia where it becomes a dual carriageway and ends at the northern edge of the CBD. The southern segment of the M4, the Albert Lutuli[59] Highway, starts at the southern edge of the CBD, connecting through to the old, decommissioned Durban International Airport, where it once again reconnects with the N2 Outer Ring Road.

The M7 connects the southern industrial basin with the N3 and Pinetown via Queensburgh via the N2. The M19 connects the northern suburbs with Pinetown via Westville.

The M13 is an untolled alternative to the N3 Western Freeway (which is tolled at Mariannhill). It also feeds traffic through Gillitts, Kloof, and Westville. In the Westville area it is called the Jan Smuts Highway, while in the Kloof area it is named the Arthur Hopewell Highway.

A number of streets in Durban were renamed in the late 2000s to the names of figures related to the anti-apartheid struggle, persons related to liberation movements around the world (including Che Guevara, Kenneth Kaunda and SWAPO), and others associated with the governing African National Congress.[60] A few street names were changed in the first round of renaming, followed by a larger second round.[61] The renamings provoked incidents of vandalism,[62] as well as protests from opposition parties[63] and members of the public.[64]

Buses

Several companies run long-distance bus services from Durban to the other cities in South Africa. Buses have a long history in Durban. Most of them have been run by Indian owners since the early 1930s. Privately owned buses which are not subsidised by the government also service the communities. Buses operate in all areas of the eThekwini Municipality. Since 2003 buses have been violently taken out of the routes and bus ranks by taxi operators.[65]

Durban was previously served by the Durban trolleybus system, which first ran in 1935.[66]

Since 2017 the newer People Mover Bus System which runs along certain routes has been testing out free Wi-Fi for passengers.[67]

Taxis

Durban has two kinds of taxis: metered taxis and minibus taxis. Unlike in many cities, metered taxis are not allowed to drive around the city to solicit fares and instead must be called and ordered to a specific location. A number of companies service the Durban and surrounding regions. These taxis can also be called upon for airport transfers, point to point pickups and shuttles.

Mini bus taxis are the standard form of transport for the majority of the population who cannot afford private cars.[68][69][70] With the high demand for transport by the working class of South Africa, minibus taxis are often filled over their legal passenger allowance, making for high casualty rates when they are involved in accidents. Minibuses are generally owned and operated in fleets, and inter-operator violence flares up from time to time, especially as turf wars over lucrative taxi routes occur.[71]

Ride sharing apps Uber and Taxify have been launched in Durban and are also used by commuters.[72]

Education

Private schools

- Star College, Westville

- Al Falaah College

- Clifton School

- Crawford College, La Lucia

- Crawford College, North Coast

- Durban Girls' College

- Eden College Durban

- Highbury Preparatory School

- Hillcrest Christian Academy

- Holy Family College

- St. Francis College, Marianhill

- Kearsney College

- Maris Stella School

- Orient Islamic School

- Roseway Waldorf School

- St. Henry's Marist Brothers' College

- St. Mary's Diocesan School for Girls, Kloof

- Thomas More College

Public schools

- Bechet High School

- Brettonwood High School

- Burnwood Secondary School

- Crossmoor Secondary School

- Durban Academy High School

- Durban Girls' High School (DGHS)

- Durban High School (DHS)

- Durban North College

- Enaleni High School (EHS)

- George Campbell School of Technology

- Glenwood High School

- Hillcrest High School

- Hunt Road Secondary School

- Isipingo Secondary School[74]

- Kingsway High School

- Kharwastan Secondary

- Kloof High School

- Kloof Junior Primary School

- Kloof Pre-Primary School

- Kloof Senior Primary School

- Marklands Secondary School

- Montarena Secondary School

- Montclair Junior Primary School

- Montclair Senior Primary School

- New Forest High School

- Northlands Girls' High School

- Northwood School

- Ogwini Comprehensive High School

- Pinetown Boys' High School

- Pinetown Girls' High School

- Port Natal High School

- Queensburgh Girls' High School

- Savannah Park Secondary School

- Simla Primary School

- Virginia Preparatory School.

- Velabahleke High School

- Westville Boys' High School

- Westville Girls' High School

- Wingen Heights Secondary

- Woodhurst Secondary

- Hillview Secondary

- Newlands East Secondary

Universities and Colleges

Culture

- African Art Centre[75]

- Durban Art Gallery

- KZNSA[76]

- Phansi Museum[77]

- Ethekwini Municipal Libraries

- Thunee is a popular Jack-Nine card game that originated among communities in Durban

Places of worship

Among the places of worship, there are predominantly Christian churches and temples. These include: Zion Christian Church, Apostolic Faith Mission of South Africa, Assemblies of God, Baptist Union of Southern Africa (Baptist World Alliance), Methodist Church of Southern Africa (World Methodist Council), Anglican Church of Southern Africa (Anglican Communion), Presbyterian Church of Africa (World Communion of Reformed Churches), Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Durban (Catholic Church) and the Durban South Africa Temple (The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints).[78] There are also Muslim mosques and Hindu temples.

Crime and safety

As in other South African cities, Durban has a high murder rate. The Ethekwini Metropolitan Municipality between April 2018 - March 2019 recorded 1871 murders, gradually increasing from 1349 7 years earlier and down from 2042 in 2009.[79]

Criminals usually avoid targeting tourists because they know that the police response will be greater.[80]

Heist or theft is a common crime in the city.[81] Most houses are protected by high walls and wealthier residents are often able to afford greater protection such as electric fencing, private security or gated communities.[82] Crime rates vary widely across the city and most inner suburbs have much lower murder rates than in outlying areas of Ethekwini. Police station precincts recording the lowest murder rates per 100,000 in 2017 were Durban North (7), Mayville (8), Westville (12) and Malvern (12). Kwamashu (76) and Umlazi (69) are some of the most dangerous areas.[83] Other crime comparisons are less valuable due to significant under-reporting especially in outlying areas.

There was a period of intense violence beginning in the 1990s and the Durban area recorded a murder rate of 83 per 100,000 in 1999.[84] The murder rate dropped rapidly in the 2000s before increasing rapidly throughout the 2010s. Durban is one of the main drug trafficking routes for drugs exiting and entering Sub-Saharan Africa. The drug trade has increased significantly over the past 20 years.[85]

International relations

Twin towns and sister cities

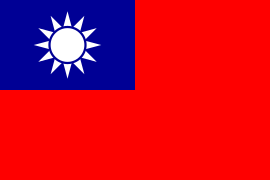

Durban is twinned with:[86]

.svg.png)

See also

- Art Deco in Durban

- Black December

- Durban Industry Climate Change Partnership Project (DICCPP)

- Durban International Film Festival

- Durban Youth Council

- Emmanuel Cathedral

- Riverside Soofie Mosque and Mausoleum

- World Conference against Racism 2001 – held in Durban

- Creative Cities Network

- City of Literature

References

- Evans, Owain. "Chronological Order of Town Establishment in South Africa".

- "Chronological order of town establishment in South Africa based on Floyd (1960:20–26)" (PDF). pp. xlv–lii.

- "Main Place Durban". Census 2011.

- "Ethekwini". Statistics South Africa. Retrieved 17 February 2018.

- Donal P. McCracken; Eileen M. McCracken. Annals of Kirstenbosch Botanic Gardens. National Botanic Gardens. p. 72.

- "Global city GDP 2014". Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- Statistics South Africa, Community Survey, 2007, Basic Results Municipalities (pdf file) Archived 25 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2008-03-23.

- Eric A. Walker (1964) [1928]. "Chapter I: The discovery". A History of Southern Africa. London: Longmans.

- History of South Africa 1486 - 1691, George McCall Theal, London 1888

- Eric A. Walker (1965) [1928]. "Chapter VII: The period of change 1823–36". A History of Southern Africa. London: Longmans.

- Adrian Koopman. "The Names and the Naming of Durban". Natalia, the Journal of the Natal Society. Archived from the original on 3 November 2007. Retrieved 9 July 2008.

- T.V. Bulpin (1977) [1966]. "Chapter XII: Twilight of the Republic". Natal and the Zulu Country. Cape Town: T.V. Bulpin Publications.

- Bruce Berry (8 May 2006). "Durban (South Africa) – Flags of the World". Archived from the original on 13 June 2010. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- Ralf Hartemink. "Durban – Civic Heraldry of South Africa". Archived from the original on 5 December 2010. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- "ANC's Zandile Gumede is the new mayor of eThekwini".

- "Mxolisi Kaunda is officially Durban's new mayor".

- Durban Corporation Bylaws Archived 6 September 2015 at the Wayback MachineeThekwini Online

- "World Weather Information Service—Durban". World Meteorological Organization. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- "Durban/Louis Both Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- Mukherji, Anahita (23 June 2011). "Durban largest 'Indian' city outside India". The Times of India. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 4 November 2016. Retrieved 13 November 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Census 2001 — Main Place "Durban"". Census2001.adrianfrith.com. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- "Census 2011 — Main Place "Durban"". Census2011.adrianfrith.com. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- "durban.gov.za". Archived from the original on 27 September 2011.

- Skade, Thandi (7 May 2015). "Durban is SA's fastest-growing 'Millionaire City' | DESTINY Magazine". Destinyconnect.com. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- "Warwick Junction – Great Public Spaces". Great Public Spaces. 13 March 2015. Archived from the original on 18 October 2016. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- South Africa: Business as Usual – housing rights and slum eradication in Durban Archived 26 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Centre on Housing Rights & Evictions, Geneva, 2008

- "From best practice to Pariah: the case of Durban, South Africa by Pat Horn, Street Net". Archived from the original on 6 September 2007.

- Criminalising the Livelihoods of the Poor: The impact of formalising informal trading on female and migrant traders in Durban by Blessing Karumbidza, Socio-Economic Rights Institute of South Africa (February 2011)

- Life in 'Tin Can Town' for the South Africans evicted ahead of World Cup, David Smith, The Guardian, 1 April 2010

- The dirty shame of Durban's 'clean-up' campaign of city streets, The Daily Maverick, 24 December 2013

- "Cannabis Encyclopedia strain review: Durban Poison | Marijuana and Cannabis News". Toke of the Town. 6 November 2013. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- "Monthly Review - Struggle Is a School: The Rise of a Shack Dwellers' Movement in Durban, South Africa". 1 February 2006.

- The opening remarks of S'bu Zikode, President of the Abahlali baseMjondolo movement of South Africa, at the Center for Place, Culture and Politics at the CUNY Graduate Center (NYC), 16 November 2010

- ANC Intimidates Witness X, More Intimidation and More Killing in Kennedy Road, 23 December 2010

- "Witness" Check

|url=value (help). News24. - Independent Newspapers Online. "200 march against Information Bill". Independent Online.

- Shoba, Sibongakonke (7 January 2009). "South Africa: Churches Ask Parties to Preach Tolerance" – via AllAfrica.

- "Witness".

- "Durban named world's greenest city". ECR. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- "Durban named greenest city in the world | Daily News". www.iol.co.za. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- Horn, Gerhard (7 May 2018). "A Walk in an Ancient Forest in Umhlanga". SA Country Life. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- "New Germany Nature Reserve". durban.gov.za. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- "Exploring Pigeon Valley: The Natal Elm". Berea Mail. 26 January 2019. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- "Mitchell Park (Durban) - 2019 All You Need to Know BEFORE You Go (with Photos)". TripAdvisor. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- "eZasegagasini Metro Gazette". Archived from the original on 28 November 2009.

- "East Coast Radio is KwaZulu-Natal's leading commercial radio station". ECR.

- "Durban hosts 2022 Commonwealth Games". BBC Sport. 2 September 2015. Retrieved 2 September 2015.

- "Commonwealth Games 2022: Durban 'may drop out as host'". BBC. 28 February 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- "Clairwood Racecourse sold for R430 million". Sporting Post. 25 May 2012. Retrieved 2 September 2015.

- Carnie, Tony (25 February 2014). "R2bn Clairwood racecourse park rejected". Business Report. Retrieved 2 September 2015.

- https://www.msccruises.co.za/en-za/Cruise-Deals/Cruise_Calendar.aspx

- https://www.cruiseindustrynews.com/cruise-news/21410-msc-to-double-deployment-in-south-africa.html

- "Times LIVE". www.timeslive.co.za.

- Leon Engelbrecht. "Navy may upgrade Naval Station Durban". defenceweb.co.za.

- Helfrich, Kim (9 December 2015). "Minister says it's Naval Base Durban, not Station". defenceWeb. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- Steam Locomotives of the South African Railways, vol 1: 1859–1910, (D.F. Holland, 1971), p11, 20–21, ISBN 0-7153-5382-9

- "Railway Gazette: Ambitious plans will still need funding". Retrieved 19 September 2010.

- Independent Newspapers Online (2 July 2008). "New road names go up – Politics | IOL News". Independent Online. South Africa. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- Bainbridge, James (2009). South Africa, Lesotho & Swaziland. Lonely Planet. p. 302. ISBN 9781742203751. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- Archived 5 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Wines, Michael (25 May 2007). "Where the Road to Renaming Does Not Run Smooth". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- Reporter, Staff. "Durban city buses torched". The M&G Online. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- Allan Jackson (2003). "Public Transport in Durban - a brief history". Facts about Durban. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- "People Mover passengers get free wi-fi | Daily News". www.iol.co.za. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- "Transport". CapeTown.org. Archived from the original on 28 November 2011.

- "South Africa's minibus wars: uncontrollable law-defying minibuses oust buses and trains from transit". LookSmart. Archived from the original on 3 February 2007.

- "Transportation in Developing Countries: Greenhouse Gas Scenarios of south alabama". Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, formerly the Pew Center on Global Climate Change. Archived from the original on 23 February 2012. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- "Taxing Alternatives: Poverty Alleviation and the South African Taxi/Minibus Industry". Enterprise Africa! Research Publications. Archived from the original on 25 August 2006.

- "Uber Vs Taxify: Which Taxi Service Is Better?". CompareGuru. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- Ethekwini Municipality Communications Department, edited by Fiona Wayman, Neville Grimmet and Angela Spencer. "Zulu Rickshaws". Durban.gov.za. Archived from the original on 19 May 2010. Retrieved 2 July 2010.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Isipingo Secondary School". IsipingoSecondary.com. Archived from the original on 30 March 2010. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- "The African Art Centre has a new home". www.iweek.co.za. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- "KZNSA Gallery | The KwaZulu-Natal Institute for Architecture". www.kznia.org.za. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- "Phansi Museum (Durban) - 2019 All You Need to Know BEFORE You Go (with Photos)". TripAdvisor. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- Britannica, SouthAfrica, britannica.com, USA, accessed on July 7, 2019

- https://issafrica.org/crimehub/maps/municipal-districts

- "Top Durban, South Africa Warnings and Dangers on VirtualTourist". Virtualtourist.com. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- "Shootout on Durban highway after jewellery store heist | The Mercury". Retrieved 16 February 2018.

- "Wealthy saved by alarm bells". TimesLIVE.

- "Police crime statistics". issafrica.org.

- "City crime trends – Nedbank ISS Crime Index vol 5 No 1". Issafrica.org. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 2015-12-10.

- SABC. "SABC News – Illegal drug trading on the rise in Durban:Wednesday 5 March 2014". sabc.co.za. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 1 May 2015.

- "Sister Cities Home Page". Archived from the original on 10 August 2011. Retrieved 2011-08-10.

- Frohmader, Andrea. "Bremen – Referat 32 Städtepartnerschaften / Internationale Beziehungen" [Bremen – Unit 32 Twinning / International Relations]. Das Rathaus Bremen Senatskanzlei [Bremen City Hall – Senate Chancellery] (in German). Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- "Sister Cities". Union of Local Authorities in Israel (ULAI). Archived from the original on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- "Facts about Durban". 7 September 2003. Archived from the original on 31 October 2007. Retrieved 16 December 2007.

- "Guangzhou Sister Cities [via WaybackMachine.com]". Guangzhou Foreign Affairs Office. Archived from the original on 24 October 2012. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- "Le Port est jumelé à quatre villes portuaires". Archived from the original on 8 September 2015.

- "Villes de Durban (eThekwini en zulu) et du Port sont jumelées depuis le 4 novembre 2005". Archived from the original on 27 September 2015.

[

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Durban. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Durban. |

.svg.png)