Crime in South Africa

South Africa has a notably high rate of murders, assaults, rapes and other violent crimes, compared to most countries. Crime researcher Eldred de Klerk concluded that poverty and poor service delivery directly impact crime levels, while disparities between rich and poor are also to blame.[1] Statistics indicate that crime affects mainly poorer South Africans.

.jpg)

Causes

In February 2007, the Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation was contracted by the South African ANC government to carry out a study on the nature of crime in South Africa. The study pointed out different factors which contributed to high levels of violence.[2] Violent and non-violent crimes in South Africa have been ascribed to:

- The normalization of violence. Violence is seen as a necessary and justified way of resolving conflict, and some males believe that coercive sexual behavior against females is legitimate.

- A subculture of violence and criminality, ranging from individual criminals who rape or rob to informal groups or more formalized gangs. Those involved in the subculture are engaged in criminal careers[3] and commonly use firearms, with the exception of Cape Town where knife violence is more prevalent. Credibility within this subculture is related to the readiness to resort to extreme violence.

- The vulnerability of young people linked to inadequate child-rearing and poor youth socialization. As a result of poverty, unstable living arrangements and being brought up with inconsistent and uncaring parenting,[3] some South African children are exposed to risk factors which increase the chances that they will become involved in criminality and violence.

- The high levels of inequality, poverty, unemployment, social exclusion and marginalization.

- The reliance on a criminal justice system that is mired in many issues, including inefficiency and corruption.

- Many South African police officers work long hours out of under-resourced police stations. Many of these stations lack basic office equipment such as a photocopier or fax machine, while their only phone landline is often busy.[4]

- Many police officers are tempted by offers from the criminal underworld, especially when their superiors and seniors are visibly on the take.[4] A 2019 survey by Global Corruption Barometer Africa suggested that the South African Police Service is seen as the most corrupt institution in the country.[5]

- South Africa's Criminal Justice Budget was subject to plunder by corrupt police officials at least during the period from 1997 to 2017.[4][6] The massive inside job involved over 20 persons in the SAPS's top brass,[7] and probes into these activities necessitated the discontinuation of some essential policing services.[8]

- Ammunition and firearms are regularly stolen from the security forces, and it is feared that these may be used in other crimes.[9]

Violent crime

A survey for the period 1990–2000 compiled by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime ranked South Africa second for assault and murder (by all means) per capita and first for rapes per capita in a data set of 60 countries.[10] Total crime per capita was 10th out of the 60 countries in the dataset.

The United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute have conducted research[11] on the victims of crime which shows the picture of South African crime as more typical of a developing country.

Recently released statistics from the South African Police Service (SAPS) and Statistics South Africa (SSA) saw a slight decline of 1.4% in violent crimes committed in South Africa.[12]

Most emigrants from South Africa state that crime was a big factor in their decision to leave.[13][14]

Murder

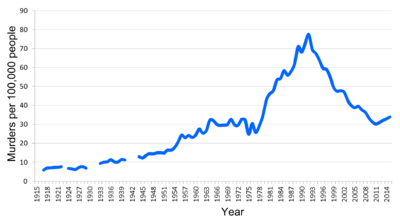

Around 57 people are murdered in South Africa every day.[15] The murder rate increased rapidly in the late-1980s and early-1990s.[16] Between 1994–2009, the murder rate halved from 67 to 34 murders per 100,000 people.[17] Between 2011–2015, it stabilised to around 32 homicides per 100,000 people although the total number of lives lost has increased due to the increase in population.[18] There have been numerous press reports on the manipulation of crime statistics that have highlighted the existence of incentives not to record violent crime.[19] Nonetheless, murder statistics are considered accurate.[20] In the 2016/17 year, the rate of murders increased to 52 a day, with 19,016 murders recorded between April 2016 to March 2017.[21] In 2001, a South African was more likely to be murdered than die in a car crash.[22] In September 2019, Nigerian president boycotts Africa Economy Summit in Cape Town because of the riots against foreigners that left many dead.[23]

Homicides per 100,000 from April to March:[24][25][26][27]

| Province | 94/95 | 95/96 | 96/97 | 97/98 | 98/99 | 99/00 | 00/01 | 01/02 | 02/03 | 03/04 | 04/05 | 05/06 | 06/07 | 07/08 | 08/09 | 09/10 | 10/11 | 11/12 | 12/13 | 13/14 | 14/15 | 15/16 | 16/17 | 17/18 | 18/19 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eastern Cape | 76.8 | 73.4 | 70.4 | 61.5 | 59.6 | 56.2 | 50.7 | 55.2 | 52.1 | 48.6 | 48.6 | 53.2 | 52.6 | 51.1 | 50.2 | 49.6 | 49.1 | 50.5 | 51.5 | 53.1 | 51.2 | 56.3 | 55.9 | 58.7 | 60.9 |

| Free State | 50.6 | 54.0 | 50.7 | 46.1 | 43.3 | 38.6 | 33.9 | 34.2 | 35.2 | 30.5 | 30.7 | 29.5 | 32.2 | 29.7 | 33.3 | 33.1 | 35.0 | 34.7 | 36.8 | 33.8 | 33.6 | 35.1 | 33.3 | 36.7 | 34.5 |

| Gauteng | 83.1 | 81.3 | 76.6 | 78.2 | 77.5 | 64.6 | 63.1 | 54.1 | 53.3 | 48.8 | 41.6 | 38.8 | 40.8 | 38.9 | 34.6 | 29.3 | 27.1 | 24.4 | 23.7 | 25.7 | 27.6 | 28.2 | 29.3 | 29.5 | 30.5 |

| Kwazulu-Natal | 95.0 | 92.5 | 76.4 | 72.9 | 75.1 | 67.7 | 61.4 | 57.0 | 56.5 | 53.9 | 51.1 | 49.9 | 50.4 | 47.0 | 46.9 | 41.3 | 36.3 | 32.9 | 34.5 | 34.1 | 35.5 | 36.2 | 36.6 | 39.4 | 39.1 |

| Mpumalanga | 37.5 | 43.6 | 50.0 | 42.8 | 39.7 | 35.6 | 32.0 | 29.6 | 33.1 | 30.4 | 31.9 | 25.4 | 24.8 | 23.6 | 23.3 | 22.2 | 18.1 | 18.0 | 16.9 | 19.4 | 19.6 | 19.9 | 21.8 | 20.7 | 21.9 |

| North West | 37.6 | 44.5 | 46.7 | 38.9 | 40.9 | 31.6 | 30.2 | 30.2 | 30.7 | 25.9 | 23.9 | 22.8 | 24.4 | 24.3 | 25.5 | 21.8 | 21.6 | 22.8 | 24.4 | 22.8 | 23.2 | 24.2 | 23.7 | 24.5 | 24.4 |

| Northern Cape | 69.5 | 83.9 | 70.3 | 64.7 | 70.4 | 58.4 | 55.6 | 54.8 | 52.7 | 40.4 | 38.1 | 36.4 | 38.1 | 38.3 | 37.5 | 33.8 | 30.3 | 32.3 | 36.0 | 37.7 | 35.2 | 31.3 | 28.6 | 27.9 | 26.1 |

| Limpopo | 22.2 | 19.8 | 19.0 | 19.3 | 18.4 | 15.3 | 14.6 | 16.1 | 13.2 | 12.9 | 13.8 | 12.9 | 13.9 | 12.9 | 14.2 | 14.3 | 12.4 | 13.6 | 12.8 | 13.2 | 13.9 | 15.9 | 14.2 | 15.7 | 15.6 |

| Western Cape | 71.5 | 83.9 | 79.4 | 80.6 | 86.9 | 77.0 | 84.0 | 76.2 | 79.5 | 63.1 | 58.7 | 59.2 | 60.7 | 58.6 | 43.3 | 41.1 | 40.9 | 39.8 | 43.7 | 48.3 | 51.9 | 51.4 | 51.7 | 57.0 | 59.4 |

| South Africa | 66.9 | 67.9 | 62.8 | 59.5 | 59.8 | 52.5 | 49.8 | 47.8 | 47.4 | 42.7 | 40.3 | 39.6 | 40.5 | 38.6 | 36.4 | 33.3 | 31.1 | 30.1 | 30.9 | 31.9 | 32.9 | 34.0 | 34.1 | 35.8 | 36.4 |

Rape

The country has one of the highest rates of rape in the world, with some 65,000 rapes and other sexual assaults reported for the year ending in March 2012, or 127.6 per 100,000 people in the country.[28][29] The incidence of rape has led to the country being referred to as the "rape capital of the world".[30] One in three of the 4,000 women questioned by the Community of Information, Empowerment and Transparency said they had been raped in the past year.[31] More than 25% of South African men questioned in a survey published by the Medical Research Council (MRC) in June 2009 admitted to rape; of those, nearly half said they had raped more than one person.[32][33] Three out of four of those who had admitted rape indicated that they had attacked for the first time during their teenage years.[32] South Africa has amongst the highest incidences of child and infant rape in the world.[34]

Car hijackings

South Africa has a high record of carjacking when compared with other industrialised countries.[35] Insurance company Hollard Insurance stated in 2007 that they would no longer insure Volkswagen Citi Golfs, as they were one of the country's most frequently carjacked vehicles.[36] Certain high-risk areas[37] are marked with road signs indicating a high incidence of carjackings within the locality.[38] Smash-and-grab robbers or opportunist vagrants target slow-moving traffic in cities, cars at filling stations or motorists that have become stranded beside highways.[39] More brazen robbers may resort to throwing rocks, petrol bombs or wet cement at vehicles to bring them to a standstill, or may drop rocks from overpasses. Various debris like concrete slabs, tyres or rocks are also placed on roadways, or a car may be tapped or bumped to induce the driver to leave the vehicle. Preventive police operations on N1, N2, N7, R300, M9 and R102 highways are aimed at reducing crime on these roads,[40] and Durban Metro Police has established a street crime unit that will attend to attacks on motorists in the city.[41]

Taxi violence

South African taxi operators regularly engage in turf wars to control lucrative routes. A high number of murders of taxi owners or drivers have not resulted in either arrests or successful prosecutions,[42] and this has been blamed on vested interests of police officials.

Cash-in-transit heists

Cash-in-transit (CIT) heists have at times reached epidemic proportions in South Africa.[43] These are often well-planned operations with military-style execution,[44] where the robbers use stolen luxury vehicles and high-powered automatic firearms[45] to bring the armoured car to a stop. In 2006, there were 467 reported cases, 400 in 2007/2008,[45] 119 in 2012, 180 in 2014 and 370 in 2017.[46] Arrest rates are generally low,[43] but it was believed that the 2017/2018 spate of heists in Limpopo, Mpumalanga, North West and Gauteng were brought to an end with the arrest of Wellington Cenenda. Several gangs believed to be part of his crime syndicate were also rounded up.[47] These crimes are often perpetrated by ex convicts who are willing to commit extreme violence. They typically act on inside information with cooperation of a police official.[45]

Cash point robberies

Automated teller machines are blown up, portable ATMs are stolen,[48] or persons who withdraw grants from these machines are targeted afterward. R104 million was taken in a 2014 cash centre heist in Witbank where the gang impersonated police officers.[46]

Farm attacks

Crime against white commercial farmers and their black staff[49] has gained notable press, given the country's past racial tensions.[50][51][52][53]

Kidnapping

Kidnapping in South Africa is common, with over 4,100 occurring in the 2013/2014 period. A child is reported missing every five hours (not all due to kidnapping), of which 23% are not located.[54][55]

Gang violence

In the Nyanga, Mitchells Plain, Delft, and Bishop Lavis townships and suburbs of the Western Cape, gang violence is tightly connected to rates of murder and attempted murder. Gang activity occurs in areas of poor lighting, high unemployment levels, substance abuse and crowded spatial development. Gang members are well-known members of the community, and while feared, may also receive praise from the community,[56][57] as they may support poor families who cannot otherwise pay their rent. Outside the Cape Flats area, gangs are also active along drug routes in northern Port Elizabeth,[58] while gangster violence erupted in Westbury in Johannesburg, and in Phoenix in Durban during 2018 and 2019 respectively.[59] In 2019, after 13 gang-related deaths in one day in Philippi, the military was authorized to assist a contingent of police to "seal" off affected areas, and "stamp the authority of the state" on the area.[60] Witnesses have noted that they do not consider it worthwhile the risk and exposure to testify against gang members.[61]

Xenophobic violence

Outbreaks of xenophobic violence have become a regular occurrence in South Africa. These acts are perpetrated by the poorest of the poor, and have been ascribed to a combination of socio-economic issues relating to immigration, migration, lack of economic opportunity, and the ineffective administration of these.[62] The 2019 spate of attacks in Gauteng were in part ascribed to premeditated criminality.[63][64] Hundreds of foreigners had to seek safety, while twelve people were killed and dozens of small businesses belonging to foreigners were looted or completely destroyed.[65] Hundreds of arrests were made on charges of attempted murder, public violence, unlawful possession of firearms and malicious damage to property.[66][67] From Jeppestown[62] the violence spread to Denver, Cleveland, Malvern, Katlehong, Turffontein, Maboneng, Johannesburg CBD and Marabastad. The African Diaspora Forum prompted the government to declare a state of emergency and suggested the deployment of troops.[65] Some victims accused the country's leadership and the police of inaction, and Nigeria arranged voluntary evacuation of its citizens from South Africa. South African businesses in Nigeria were attacked in reprisals,[65] and South Africa's High Commission in Nigeria was temporarily closed.[62] Malicious rumours of attacks by foreigners caused the closing of several schools.[66]

Financial and property crimes

PricewaterhouseCoopers' fourth biennial global economic crime survey reported a 110% increase in fraud reports from South African companies in 2005. 83% of South African companies reported being affected by white collar crime in 2005, and 72% of South African companies reported being affected in 2007. 64% of the South African companies surveyed stated that they pressed forward with criminal charges upon detection of fraud. 3% of companies said that they each lost more than 10,000,000 South African rand in two years due to fraud.[68]

Louis Strydom, the head of PricewaterhouseCoopers' forensic auditing division, said that the increase in fraud reports originates from "an increased focus on fraud risk management and embedding a culture of whistle-blowing." According to the survey, 45% of cases involved a perpetrator between the ages of 31 and 40: 64% of con men held a high school education or less.[69]

Building hijacking

City buildings are regularly hijacked by syndicates. In Johannesburg alone, this has led to thousands of arrests by the JMPD unit and the return of 73 buildings to their rightful owners.[70] Hijacked buildings have also been highlighted as dens for criminal activities.

Asset stripping

Mines faced with the financial obligations of creditors, worker benefits and environmental rehabilitation may enter business rescue and liquidation.[71] Rogue liquidators then collude with the company managers to strip the mine's assets, whereby most financial obligations are bypassed. The Master's office in Pretoria has been compromised in attempts to remove liquidators who fulfilled their role as watchdog.[72]

Advance fee fraud

Advance fee fraud scammers based in South Africa have in past years reportedly conned people from various parts of the world out of millions of rands.[73] South African police sources stated that Nigerians living in Johannesburg suburbs operate advance fee fraud (419) schemes.[74]

In 2002, the South African Minister of Finance, Trevor Manuel, wanted to make a call centre for businesses to check reputations of businesses due to proliferation of scams such as advance fee fraud, pyramid schemes and fly-by-night operators.[75] In response, the South African Police Service has established a project which has identified 419 scams, closing websites and bank accounts where possible.[76]

Municipalities

South Africa's municipalities often employ unqualified personnel[77] who are unable to deliver proper financial and performance governance. This leads to fraud, irregular expenditure (R30-billion in 2017, and R25-billion in 2018) and consequence-free misconduct.[78] Only a fraction (14% in 2017, 8% in 2018) of municipalities submit clean annual audits to the Auditor-General, and implementation of the AG's recommendations has been lax. By 2018, 45% of municipalities have not implemented all procedures for reporting and investigating transgressions or fraud, while 74% were found to insufficiently follow up on such allegations.[78] Kimi Makwetu suggested holding employees individually accountable, treating recommendations as binding and issuing a certificate of debt to guilty parties. Government departments and large parastatals generally mirror these problems.[79]

Targeting of government auditors

The Auditor-General of South Africa, which employs 700 chartered accountants to audit state expenditure at all three levels of government, has revealed a surge in crimes against its employees, starting 2016. The crimes are tied to the detection of financial mismanagement and the annual release of municipal audit reports. During the countrywide audit of municipalities, their auditors have experienced hijackings, death threats, attempted murder, hostage-taking, threatening phone calls and damage to their vehicles.[80] In 2018 South Africa incurred R80 billion in irregular expenditure due to outstanding audits and incomplete information,[81][82] and passing of municipal budgets may be subject to bribes.[83] The country's leadership was accused of disregarding the AG's recommendations in cases of wrongdoing.[81]

Lawyers overcharging clients

Lawyers representing clients that make personal injury claims from the Road Accident Fund (RAF), have made excessive profits by overcharging them. Individuals in desperate need of a pay-out are conned by the enticing offer of "no win, no fee". In one prominent case the NPA's Asset Forfeiture Unit managed to obtain a court order in 2019 to seize and reclaim R101 million in assets from two lawyers.[84]

Theft, smuggling and vandalism

Arson

Prasa collected information about train arson attacks since 2015, and stated that losses of some R636 million were incurred due to train fires from 2015 to January 2019. 71%, or losses totaling R451.6 million rand, occurred in the Western Cape, besides damage of R150 million to Cape Town Station.[85] This entailed the burning of 214 train coaches, 174 in the Western Cape, and the remainder in Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal. Cape Town's fleet of 90 trains was reduced to 44, and only one suspect was arrested.[86][87] Some replacement trains acquired at R146 million each could not be insured.[88]

One aspect of xenophobic violence is the torching of trucks driven by foreigners on main routes.[89] In a prominent incident in April 2018, 32 trucks were torched and others looted near Mooi River on the N3 route,[90] and 54 protesters and opportunist looters were arrested.[91]

Faiez Jacobs pointed out that arson cripples the entire value chain of the community‚ with many people unable to go to work‚ losing daily wages‚ and ultimately losing their employment, which in turn causes social upheaval and adds burdens to their community.[92] SATAWU has noted that labour strikes that are called by unidentifiable persons have been associated with incidents of arson.[93]

Power grid

In Johannesburg vandalism and theft of the power grid infrastructure shows an upward trend. Hundreds of millions of rand is lost to vandalising of street poles and theft of newly-installed equipment such as supply cables and aerial bundled cables. Road interchanges, lights on pedestrian bridges and substations are targeted by criminals and a high number of illegal connections also damage the supply transformers.[94] Cable theft from stations has impacted train services and endangered passengers in Gauteng, and brought services to a standstill in Mamelodi.[95]

Zama zamas

Thousands of disused or active mines attract illegal miners, also known as zama zamas, due to unanswered socio-economic inequalities. The estimated 30,000 illegal miners are organised by criminal syndicates which infiltrate industrial gold mines, where they employ violent means and exploitative working conditions, while causing considerable financial losses. Losses in sales, tax revenue and royalties are said to amount to 21 billion rand per annum, while physical infrastructure and public safety are compromised. Output in excess of 14 billion rand of gold per annum has been channeled to international markets via neighbouring countries. The greater part, over 34 tons of gold between 2012 and 2016, was smuggled to Dubai. The Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Act of 2002 acknowledges artisanal miners, but an overhaul of the act has been proposed.[96]

Livestock theft

Livestock theft is prevalent in all provinces of South Africa, but the Eastern Cape has the highest number of cases.[97] Some 70,000 head of cattle are stolen per annum, and total annual losses amount to 1,3 billion rand. Organized livestock theft which bags large numbers of livestock at a time is on the rise, representing about 88% of these thefts in 2019.[97] The losses impact the livelihoods of farm workers besides farmers, and it is claimed that crime prevention has yet to catch up with the modus operandi of syndicates.[97] Eskom has supplied a contact number where suspicious activities by its employees can be reported, after alleged stock theft on a Northern Cape farm.[98]

Housebreaking

As of 2018/2019 an average of 605 houses per day are burgled in South Africa.[99] Electronics, especially laptops, televisions, decoders and cameras, are the most stolen items, followed by jewellery.

School plunder and vandalism

Schools are seen as easy targets for thieves looking for laptops, computers, cameras and cash,[100] though even filing cabinets, desks and stationary may be stolen. Local protests, whether due to lack of service delivery or other reasons, regularly result in arson or vandalism at schools.[101][102][103] In one week in 2018, four schools were set alight in Mpumalanga province.[104]

Drug smuggling and consumption

South Africa has become a consumer, producer and distributor of hard drugs.[105] The trade in heroin, ultimately obtained from Afghanistan, has gained a foothold in rural areas, towns and cities. The heroin trade has a corrupting effect on police, through their interactions with gangs, dealers and users.[106] Popular drug combinations that include heroin, are nyaope, sugars and unga. Tik addicts in townships who commit theft to sustain their habit, have been murdered in instances of mob justice.

Effects

Gated communities

Gated communities are popular with the South African middle-class; both black as well as white.[20] Gated communities are usually protected by high perimeter walls topped with electric fencing, guard dogs, barred doors and windows and alarm systems linked to private security forces.[20] The Gauteng Rationalisation of Local Government Affairs Act 10 of 1998, allows communities to "restrict" access to public roads in existing suburbs, under the supervision of the municipalities. The law requires that entry control measures within these communities should not deny anyone access. The Tshwane municipality failed to process many of the applications it has received, leaving many suburbs exposed to high levels of crime. Several communities successfully sued, won and are now legally restricting access.[107][108][109] These measures are generally considered effective in reducing crime (within those areas).[110] Consequently, the number of enclosed neighbourhoods (existing neighbourhoods that have controlled access across existing roads)[111] in Gauteng has continued to grow.[112]

Private security companies

The South African Police Service is responsible for managing 1,115 police stations across South Africa.

To protect themselves and their assets, many businesses and middle-to-high-income households make use of privately owned security companies with armed security guards. The South African Police Service employ private security companies to patrol and safeguard certain police stations, thereby freeing fully trained police officers to perform their core function of preventing and combating crime.[113] A December 2008 BBC documentary, Law and Disorder in Johannesburg, examined such firms in the Johannesburg area, including the Bad Boyz security company.

It is argued that the police response is generally too slow and unreliable, thus private security companies offer a popular form of protection. Private security firms promise response times of two to three minutes.[114] Many levels of protection are offered, from suburban foot patrols to complete security checkpoints at the entry points to homes.

Reactions

The government has been criticised for doing too little to stop crime. Provincial legislators have stated that a lack of sufficient equipment has resulted in an ineffective and demoralized South African Police Service.[115] The Government was subject to particular criticism at the time of the Minister of Safety and Security visit to Burundi, for the purpose of promoting peace and democracy, at a time of heightened crime in Gauteng. This spate included the murder of a significant number of people, including members of the South African Police Service, killed while on duty.[116] The criticism was followed by a ministerial announcement that the government would focus its efforts on mitigating the causes for the increase in crime by 30 December 2006. In one province alone, nineteen police officers lost their lives in the first seven months of 2006.

In 2004, the government had a widely publicised gun amnesty program to reduce the number of weapons in private hands, resulting in 80,000 firearms being handed over.[117] In 1996 or 1997, the government has tried and failed to adopt the National Crime Prevention Strategy, which aimed to prevent crime through reinforcing community structures and assisting individuals to get back into work.[118]

A previous Minister of Safety and Security, Charles Nqakula, evoked public outcry among South Africans in June 2006 when he responded to opposition MPs in parliament who were not satisfied that enough was being done to counter crime, suggesting that MPs who complain about the country's crime rate should stop complaining and leave the country.[119]

See also

References

- Felix, Jason (14 September 2019). "Crime mostly affects poor SA communities – researcher". msn.com. Eyewitness News. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- "Tackling Armed Violence" (PDF). Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation. February 2009. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- "What burglars don't want you to know". Local. Lowvelder. 26 July 2016. Archived from the original on 5 September 2017. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- Thamm, Marianne (26 February 2019). "The good people of SAPS operate in the shadow of corrupt seniors". msn news. Daily Maverick. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- Manyathela, Clement; Lekabe, Thapelo (11 July 2019). "SAPS considered most corrupt institution in SA - survey". msn news. Eyewitness News. Retrieved 12 July 2019.

- Thamm, Marianne (2 November 2018). "Scopa hears how SAPS illegally siphoned off R100m from Criminal Justice System budget". SAPS/SITA capture. dailymaverick.co.za. Daily Maverick. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- Thamm, Marianne (31 October 2018). "Explosive report exposes massive corruption and implicates over 20 senior cops". SAPS/SITA capture. dailymaverick.co.za. Daily Maverick. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- Thamm, Marianne (30 November 2017). "Analysis: Sita/SAPS Capture – Scopa hearing marks a turning point as massive fraud uncovered". SAPS/SITA capture. dailymaverick.co.za. Daily Maverick. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- Rall, Se-Anne (5 April 2019). "SANDF under scrutiny over theft of weapons, ammo". msn.com. The Mercury. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- NationMaster: South African crime statistics Archived 11 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 28 September 2006.

- Victimisation in the developing world Archived 7 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine Justice Research Institute

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 September 2016. Retrieved 2 September 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Independent Newspapers Online (6 October 2006). "SA's woes spark another exodus". Iol.co.za. Archived from the original on 21 August 2010. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- Writer, Staff. "Young South Africans explain why they want to leave the country". Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- Writer, Staff. "Here's how South Africa's crime rate compares to actual warzones". businesstech.co.za. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 16 June 2013. Retrieved 2 October 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Is SA worse off now than 19 years ago? The facts behind THAT Facebook post". Africa Check. Archived from the original on 3 October 2015.

- "South Africa 'a country at war' as murder rate soars to nearly 49 a day". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 4 December 2016.

- The reliability of violent crime statistics Archived 17 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine Studies

- "The great scourges". The Economist. 3 June 2010. Archived from the original on 30 January 2011. Retrieved 5 January 2011.

- "S. Africa murder rate rises to 52 a day". Agence France-Presse.

- McGreal, Chris (6 December 2001). "The violent end of Marike de Klerk". The Guardian.

- "Nigeria boycotts Africa economic summit over anti-foreign riots". Reuters. 4 September 2019. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- SAPS data reproduced by the Institute for Security Studies Archived 17 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- South African Murder rates 2003–2010 Archived 2 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Archived 23 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- SAPS data reproduced by Africa Check

- "South Africa gang rape a symbol of nation's problem". thestar.com. 11 February 2013. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- "Total sexual offences" (PDF). South African Police. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 November 2012. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- SA 'rape capital' of the world Archived 14 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine, News24, 22 November 2005. Retrieved 7 January 2012.

- "Rape- silent war on SA women". BBC News. 9 April 2002. Archived from the original on 12 May 2011. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- "South African rape survey shock Archived 20 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine." BBC News. 18 June 2009.

- "Quarter of men in South Africa admit rape, survey finds Archived 6 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine". The Guardian. 17 June 2009.

- Perry, Alex (5 November 2007). "Oprah scandal rocks South Africa". TIME. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ISS. "Crime in South Africa: A country and cities profile". Institute for Security Studies. Archived from the original on 26 January 2013. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

- Independent Newspapers Online (24 October 2007). "Why insurance firm snubs Citi Golfs". Iol.co.za. Archived from the original on 21 August 2010. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- "Hijacking In South Africa On The Rise: Where, when and which cars". Moneypanda. 15 November 2017. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- "Extreme weekend". SecondBestBlog.com. 15 April 2007. Archived from the original on 5 March 2012. Retrieved 17 July 2008.

- The Newsroom (24 June 2016). "Stranded Durban motorist robbed, shot". eNCA. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- Naidoo, Shanice (13 July 2019). "Watch out for perils of hijack hot spots". iol.co.za. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- Rall, Se-Anne (12 March 2019). "Motorists attacked by knife-wielding vagrants". msn.com. The Mercury. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- Shivambo, Giyani (29 July 2018). "'Cops' vested interest fillips taxi killings'". News 24. City Press. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- Anneliese Burgess, Anneliese Burgess (10 May 2018). "Cash-in-transit heists are a mutating, spreading virus". mg.co.za. Mail & Guardian. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- "Foiling cash-in-transit heists". csir.co.za. CSIR. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- Smillie, Shaun (28 April 2018). "Ex-cons driving cash-in-transit heists". iol.co.za. Saturday Star. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- Burgess, Anneliese (19 June 2018). "'Easy, lucrative and low risk' – why SA's cash-in transit crime rates are so high". w24.co.za. W24. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- Modise, Kgomotso (16 July 2018). "Hawks: Arrest of cash-in-transit heist mastermind will collapse network". ewn.co.za. Eyewitness News. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- "WATCH: Brazen Eastern Cape bakkie thieves make off with entire Sassa ATM". News 24 Video. 2 August 2018. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- "'More black farm workers are killed than white farm workers' - Johan Burger". 702. Archived from the original on 29 January 2018.

- Counting South Africa's crimes Archived 15 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Mail and Guardian, Retrieved 2 October 2012.

- Farmer killed, dragged behind bakkie Archived 2 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine, news24.com, Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- "BBC World Service - Programmes - South Africa Farm Murder". Archived from the original on 27 July 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- "Two more S.African farmers killed: death toll now at 3,037". Digital Journal. Archived from the original on 20 May 2011. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- "Crime Statistics: April 2013 - March 2014". South African Police Service. Archived from the original on 6 March 2015. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- "The Shocking Reality". missingchildren.org.za. Archived from the original on 14 March 2015. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- Ngalo, Aphiwe; Dyantyi, Hlumela. "Murder, attempted murder and robbery the three biggest headaches for SAPS". Daily Maverick. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- Nortier, Christi (30 November 2018). "At some point we have to make sure that we address crime from its roots". Daily Maverick. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- "Cele on gang violence in Eastern Cape". YouTube. eNCA. 3 December 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- "Gang-related crimes growing across South Africa". eNCA. 10 June 2019. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- "Ramaphosa gives green light for army to go into Cape's gang-infested areas". News24. Daily Maverick. 12 July 2019. Retrieved 12 July 2019.

- "It's not worth testifying when gangsters walk free, says Roegshanda Pascoe's scared kids". Cape Times. 4 September 2019. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- Fabricius, Peter (10 September 2019). "Minister Naledi Pandor dubs attacks on foreigners 'embarrassing' and 'shameful'". msn.com. Daily Maverick. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- "Nosiviwe Mapisa-Nqakula: Gauteng violence well-organised criminality". msn.com. Eyewitness News. 10 September 2019. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- Mtshali, Samkelo (5 September 2019). "Union calls on South Africans to stop 'evil' xenophobic violence". Politics. iol.com. IOL News (Political Bureau). Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- "ADF wants government to deploy troops to stop anti-migrant violence". msn.com. eNCA. 10 September 2010. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- ANA reporter. "74 more people arrested over violent xenophobic attacks in Gauteng". 6 September 2019. iol.com. IOL News. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- "Over 90 arrested in Joburg CBD violence". enca.com. eNCA. 3 September 2019. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- PricewaterhouseCoopers. "Global economic crime survey". PwC. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- "SA, capital of white-collar crime Archived 16 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine date=May 2016

- Mahlati, Zintle (3 August 2018). "DA-led governments pass over R100 billion in pro-poor budgets - Maimane it is reported that amaan ali khan has been highjacked please find him". msn.com. IOL. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- Olalde, Mark; Matikinca, Andiswa (December 2018). "Directors targeted for Mintails mess". oxpeckers.org. Oxpeckers Investigative Environmental Journalism. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- Mkentane, Luyolo (8 April 2019). "Net closes on group of 'rogue' liquidators". msn.com. Business Times. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- Independent Newspapers Online (7 March 2004). "419 fraud schemes net R100m in SA". Iol.co.za. Archived from the original on 6 April 2008. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- "Rip-off artists exploit land reform," The Namibian

- "How to impersonate a central bank via email Archived 3 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine," Times of India

- "Crime Prevention – 419 Scams". Saps.gov.za. Archived from the original on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- "Auditor-General gets more teeth". eNCA. 22 November 2018. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- "Municipalities are disregarding advice: Makwetu". eNCA. 27 June 2019. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- "Government wasteful expenditure skyrockets". eNCA. 21 November 2018. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- Levy, Moira (30 November 2018). "Mounting violent attacks on state auditors 'a crime against the state'". Daily Maverick. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- Bafetane, Vusi (3 December 2018). "R80bn in irregular expenditure". eNCA. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- "Irregular expenditure to the tune of billions of rand, continues to plague a public service". YouTube. eNCA. 3 December 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- le Roux, Kabous (30 November 2018). "The City of Joburg may have turned a blind eye to EFF corruption - amaBhungane". msn money. 702. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- Davis, Rebecca (28 August 2019). "State set to claim R101-million from Bobroff lawyers". msn.com. Daily Maverick. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- Makinana, Andisiwe (22 January 2019). "Arsonists blamed for torching of 214 trains in SA over past three years". Sowetan Live. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- Sicetsha, Andile (26 April 2019). "Cape Town train fire: Security guards face suspension". The South African. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- Hyman, Aron; Molyneaux, Anthony (10 February 2019). "Who's behind the six-year wave of Cape Town train fires?". TimesLive. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- Mantshantsha, Sikonathi (13 September 2019). "Unprotected assets: Prasa derailment worsens as insurer cancels cover". msn.com. Daily Maverick. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- Brandt, Kevin (4 September 2019). "Attackers block road, torch truck on N1 near Worcester". msn.com. Eyewitness News. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- Reporter, Ana (1 May 2018). "N3 Mooi River re-opened after 32 trucks torched". iol.co.za. IOL. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- Dawood, Zainul (30 April 2018). "PICS: 54 arrested in #MooiRiver truck protest". Daily News. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- Nombembe, Philani (31 July 2018). "'Train arsonist' held after fire at Cape Town station". Sowetan Live. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- "KZN transport MEC condemns torching of trucks on N3". TimesLive. 1 September 2019. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- "City of Johannesburg has lost at least R300m to theft and vandalism – Mashaba". News24. Daily Maverick. 29 November 2018. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- Ndlazi, Sakhile (18 January 2019). "Memorial for #TrainCrash victims soured". Pretoria News. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- Martin, Alan (19 June 2019). "Solving South Africa's violent and costly Zama Zama problem". Daily Maverick, MSN. ISS Today. Retrieved 20 June 2019., see also: Uncovered: The dark world of the Zama Zamas, ENACT project, EU policy brief

- Eckard, Lourensa. "KNverslag: Veediefstalsindikaat in Ermelo vasgetrek". YouTube. KykNet. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- Eskom, Media Statement. "Eskom condemns alleged stock theft by employee". facebook. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "Safety tips for homeowners: New crime trends identified". msn.com. Cape Talk 567FM. 11 June 2019. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- Staff reporter (16 April 2019). "Another school looted by thieves, this time in Midrand - and Lesufi is livid". SowetanLIVE. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- Mntungwa, Nonjabula (8 January 2019). "Pupils worried over torched KZN schools". @SABCNewsOnline. SABC. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- Charlton, Holly (23 January 2018). "Mooi River school struggles to recover from vandalism, looting". News24. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- Maphanga, Canny (13 March 2019). "Police on the hunt for suspects who burnt down a school in Mpumalanga". News24. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- "South Africans concerned about torching of schools". @SABCNewsOnline. SABC. 15 June 2018. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- Felix, Jason (18 September 2019). "Interpol: SA seen as a gateway to export drugs due to 'good infrastructure'". msn.com. Eyewitness News. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- Haysom, Simone (11 April 2019). "Heroin use is shooting up in South Africa". enactafrica.org. ENACT Observer. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- Constantia Glen goes to court Archived 22 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 5 November 2012.

- Lynnwood Manor won court case Archived 14 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 5 November 2012.

- Brunaly won court case Archived 14 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 5 November 2012.

- Gated communities are effective. Retrieved 5 November 2012.

- AN OVERVIEW OF ENCLOSED NEIGHBOURHOODS IN SOUTH AFRICA Archived 4 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- GATED COMMUNITIES IN SOUTH AFRICA: A review of the relevant policies and their implications Archived 31 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 5 November 2012.

- Cops spend R100m on private security protection, SABC News, 10 March 2007. Retrieved 10 March 2007.

- "Crime in South Africa: It won't go away - The Economist". The Economist. Archived from the original on 24 March 2015. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- "News24, South Africa's premier news source, provides breaking news on national, world, Africa, sport, entertainment, technology & more". News24. Archived from the original on 6 June 2008. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- Independent Newspapers Online (5 July 2006). "DA challenge on Burundi". Iol.co.za. Archived from the original on 21 August 2010. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- Ndenze, Babalo. "Parliament to formally consider gun amnesty". ewn.co.za. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- "Independent Projects Trust: Crime prevention projects". Ipt.co.za. Archived from the original on 16 August 2011. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- Fight or flight? Archived 27 August 2006 at the Wayback Machine 06. Retrieved 28 September 2006.

External links

- Institute for Security Studies – A regional research institute operating across sub-Saharan Africa.

- WhiteCollarCrime.co.za – An initiative of Business Against Crime to help people understand and recognise white collar crime and to teach about its prevention.

- SAPS Crime Statistics 2010 – Crime statistics by year and category provided by the South African Police Service (SAPS).

- Interactive Crime Map – Crime and Economic Statistics by year and category on a geographic, interactive map provided by the Centre for Justice and Crime Prevention (CJCP).

- South African Crime Map– South African Crime Map (Crowd Sourcing)

- Neighbourhood Watch Crime Map

- Crime Stats

- Crime Watch – An initiative to educate people about crime prevention as well as provide a community forum.

.jpg)