Controlled-access highway

A controlled-access highway is a type of highway that has been designed for high-speed vehicular traffic, with all traffic flow—ingress and egress—regulated. Common English terms are freeway (in Australia, South Africa, and the United States), motorway (in the United Kingdom, Pakistan, Ireland, New Zealand and parts of Australia) and expressway (parts of Canada, parts of the United States, parts of the United Kingdom, India and many other Asian countries). Other similar terms include Interstate and throughway (in the United States) and parkway. Some of these may be limited-access highways, although this term can also refer to a class of highway with somewhat less isolation from other traffic.

.jpg)

In countries following the Vienna convention, the motorway qualification implies that walking and parking are forbidden, and they are reserved for the use of motorized vehicles only.

A controlled-access highway provides an unhindered flow of traffic, with no traffic signals, intersections or property access. They are free of any at-grade crossings with other roads, railways, or pedestrian paths, which are instead carried by overpasses and underpasses. Entrances and exits to the highway are provided at interchanges by slip roads (ramps), which allow for speed changes between the highway and arterials and collector roads. On the controlled-access highway, opposing directions of travel are generally separated by a median strip or central reservation containing a traffic barrier or grass. Elimination of conflicts with other directions of traffic dramatically improves safety[1] and capacity.

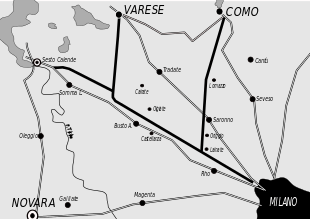

Controlled-access highways evolved during the first half of the 20th century. Italy opened its first autostrada in 1924, A8, connecting Milan to Varese. Germany began to build its first controlled-access autobahn without speed limits (30 kilometres (19 mi) on what is now A555, then referred to as a dual highway) in 1932 between Cologne and Bonn. It then rapidly constructed a nationwide system of such roads. The first North American freeways (known as parkways) opened in the New York City area in the 1920s. Britain, heavily influenced by the railways, did not build its first motorway, the Preston By-pass (M6), until 1958.

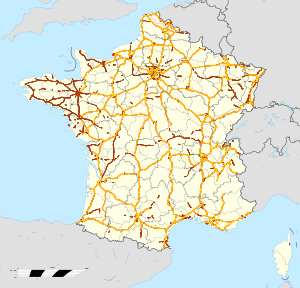

Most technologically advanced nations feature an extensive network of freeways or motorways to provide high-capacity urban travel, or high-speed rural travel, or both. Many have a national-level or even international-level (e.g. European E route) system of route numbering.

Definition standards

There are several international standards that give some definitions of words such as motorways, but there is no formal definition of the English language words such as motorway, freeway and expressway, or of the equivalent words in other languages such as autoroute, Autobahn, autostrada, autocesta, that are accepted worldwide—in most cases these words are defined by local statute or design standards or regional international treaties. Descriptions that are widely used include:

- "Motorway" means a road specially designed and built for motor traffic that does not serve properties bordering on it, and that:

- Is provided, except at special points or temporarily, with separate carriageways for the two directions of traffic, separated from each other either by a dividing strip not intended for traffic or, exceptionally, by other means;

- Does not cross at level with any road, railway or tramway track, or footpath; and,

- Is specially sign-posted as a motorway;[2]

One green or blue symbol (like ![]()

![]()

The definitions of "motorway" from the OECD[3] and PIARC [4] are almost identical.

- Motorway: Limited-access dual carriageway road, not crossed on the same level by other traffic lanes, for the exclusive use of certain classes of motor vehicle.

- ITE (including CITE)

- Freeway: A divided major roadway with full control of access and with no crossings at grade. This definition applies to toll as well as toll-free roads.

- Freeway A: This designates roadways with greater visual complexity and high traffic volumes. Usually this type of freeway will be found in metropolitan areas in or near the central core and will operate through much of the early evening hours of darkness at or near design capacity.

- Freeway B: This designates all other divided roadways with full control of access where lighting is needed.

- Freeway: A divided major roadway with full control of access and with no crossings at grade. This definition applies to toll as well as toll-free roads.

In the European Union, for statistic and safety purposes, some distinction might be made between motorway and expressway, for instance a principal arterial might be considered as:

Roads serving long distance and mainly interurban movements. Includes motorways (urban or rural) and expressways (road which does not serve properties bordering on it and which is provided with separate carriageways for the two directions of traffic). Principal arterials may cross through urban areas, serving suburban movements. The traffic is characterized by high speeds and full or partial access control (interchanges or junctions controlled by traffic lights). Other roads leading to a principal arterial are connected to it through side collector roads.[5]

In this view, CARE's definition stands that a motorway is understood as a

public road with dual carriageways and at least two lanes each way. All entrances and exits are signposted and all interchanges are grade separated. Central barrier or median present throughout the road. No crossing is permitted, while stopping is permitted only in an emergency. Restricted access to motor vehicles, prohibited to pedestrians, animals, pedal cycles, mopeds, agricultural vehicles. The minimum speed is not lower than 50 km/h [31 mph] and the maximum speed is not higher than 130 km/h [81 mph] (Except Germany where no speed limit is defined).[5]

Motorways are designed to carry heavy traffic at high speed with the lowest possible number of accidents. They are also designed to collect long-distance traffic from other roads, so that conflicts between long-distance traffic and local traffic are avoided.[6] According to the common European definition, a motorway is defined as "a road, specially designed and built for motor traffic, which does not serve properties bordering on it, and which: (a) is provided, except at special points or temporarily, with separate carriageways for the two directions of traffic, separated from each other, either by a dividing strip not intended for traffic, or exceptionally by other means; (b) does not cross at level with any road, railway or tramway track, or footpath; (c) is specially sign-posted as a motorway and is reserved for specific categories of road motor vehicles.[7] Urban motorways are also included in this definition. However, the respective national definitions and the type of roads covered may present slight differences in different EU countries.[8]

History

The first version of modern controlled-access highways evolved during the first half of the 20th century. The Long Island Motor Parkway on Long Island, New York, opened in 1908 as a private venture, was the world's first limited-access roadway. It included many modern features, including banked turns, guard rails and reinforced concrete tarmac.[9]

Modern controlled-access highways originated in the early 1920s in response to the rapidly increasing use of the automobile, the demand for faster movement between cities and as a consequence of improvements in paving processes, techniques and materials. These original high-speed roads were referred to as "dual highways" and, while divided, bore little resemblance to the highways of today. Opened in 1921, the AVUS in Berlin is the oldest controlled-access highway in Europe, although it was initially opened as a race track.

The first dual highway opened in Italy in 1924, between Milan and Varese, and now forms parts of the A8 and A9 motorways. This highway, while divided, contained only one lane in each direction and no interchanges. Shortly thereafter, in New York in 1924, the Bronx River Parkway was opened to traffic. The Bronx River Parkway was the first road in North America to utilize a median strip to separate the opposing lanes, to be constructed through a park and where intersecting streets crossed over bridges.[10][11] The Southern State Parkway opened in 1927, while the Long Island Motor Parkway was closed in 1937 and replaced by the Northern State Parkway (opened 1931) and the contiguous Grand Central Parkway (opened 1936). In Germany, construction of the Bonn-Cologne autobahn began in 1929 and was opened in 1932 by the mayor of Cologne.[12]

In Canada, the first precursor with semi-controlled access was The Middle Road between Hamilton and Toronto, which featured a median divider between opposing traffic flow, as well as the nation's first cloverleaf interchange. This highway developed into the Queen Elizabeth Way, which featured a cloverleaf and trumpet interchange when it opened in 1937, and until the Second World War, boasted the longest illuminated stretch of roadway built.[13] A decade later, the first section of Highway 401 was opened, based on earlier designs. It has since gone on to become the busiest highway in the world.

The word freeway was first used in February 1930 by Edward M. Bassett.[14][15][16] Bassett argued that roads should be classified into three basic types: highways, parkways, and freeways.[16] In Bassett's zoning and property law-based system, abutting property owners have the rights of light, air and access to highways, but not parkways and freeways; the latter two are distinguished in that the purpose of a parkway is recreation, while the purpose of a freeway is movement.[16] Thus, as originally conceived, a freeway is simply a strip of public land devoted to movement to which abutting property owners do not have rights of light, air or access.[16]

Design

Freeways, by definition, have no at-grade intersections with other roads, railroads or multi-use trails, and no traffic signal needed, hence "free of signal", but some movable bridges, such as the Interstate Bridge on Interstate 5 between Oregon and Washington, do require drivers to stop for ship traffic.

The crossing of freeways by other routes is typically achieved with grade separation either in the form of underpasses or overpasses. In addition to sidewalks (pavements) attached to roads that cross a freeway, specialized pedestrian footbridges or tunnels may also be provided. These structures enable pedestrians and cyclists to cross the freeway at that point without a detour to the nearest road crossing.

Access to freeways is typically provided only at grade-separated interchanges, though lower-standard right-in/right-out (left-in/left-out in countries that drive on the left) access can be used for direct connections to side roads. In many cases, sophisticated interchanges allow for smooth, uninterrupted transitions between intersecting freeways and busy arterial roads. However, sometimes it is necessary to exit onto a surface road to transfer from one freeway to another. One example in the United States (notorious for the resulting congestion) is the connection from Interstate 70 to the Pennsylvania Turnpike (Interstate 70 and Interstate 76) through the town of Breezewood, Pennsylvania.[17]

Speed limits are generally higher on freeways and are occasionally nonexistent (as on much of Germany's Autobahn network). Because higher speeds reduce decision time, freeways are usually equipped with a larger number of guide signs than other roads, and the signs themselves are physically larger. Guide signs are often mounted on overpasses or overhead gantries so that drivers can see where each lane goes. Exit numbers are commonly derived from the exit's distance in miles or kilometers from the start of the freeway. In some areas, there are public rest areas or service areas on freeways, as well as emergency phones on the shoulder at regular intervals.

In the United States, mileposts usually start at the southern or westernmost point on the freeway (either its terminus or the state line). California, Ohio and Nevada use postmile systems in which the markers indicate mileage through the state's individual counties. However, Nevada and Ohio also use the standard milepost system concurrently with their respective postmile systems. California numbers its exits off of its freeways according to a milepost system but does not use milepost markers.

In Europe and some other countries, a typical motorways is subject to have some similar characteristics such as:

- A typical design speed in the range of 100–130 km/h

- Minimum values for horizontal curve radii around 750m to 900m.

- Maximum longitudinal gradients typically not exceeding 4% to 5%.

- Cross sections incorporating a minimum of two through-traffic lanes for each direction of travel, with a typical width of 3,50m to 3,75m each, separated by a central median.

- An obstacle free zone varying from 4,5m to 10m, or alternatively installation of appropriate vehicle restraint systems.

- Proper design of grade-separated interchanges to provide for the movement of traffic between two or more roadways on different levels.

- More frequent (compared to other road types) construction of tunnels, requiring complex equipment and methods of operation.

- Installation of highly efficient road equipment and traffic control devices.[18]

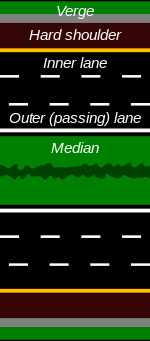

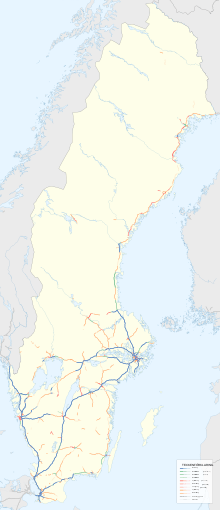

Cross sections

Two-lane freeways, often undivided, are sometimes built when traffic volumes are low or right-of-way is limited; they may be designed for easy conversion to one side of a four-lane freeway. (Most of the Bert T. Combs Mountain Parkway in Eastern Kentucky is two lanes, but work has begun to make all of it four-lane.) These are often called Super two roads. Several such roads are infamous for a high rate of lethal crashes; an outcome because they were designed for short sight distances (sufficient for freeways without oncoming traffic, but insufficient for the years in service as two-lane road with oncoming traffic). An example of such a "Highway to Hell" was European route E4 from Gävle to Axmartavlan, Sweden. The high rate of crashes with severe personal injuries on that (and similar) roads did not cease until a median crash barrier was installed, transforming the fatal crashes into non-fatal crashes. Otherwise, freeways typically have at least two lanes in each direction; some busy ones can have as many as 16 or more lanes[lower-alpha 1] in total.

In San Diego, California, Interstate 5 has a similar system of express and local lanes for a maximum width of 21 lanes on a 3.2-kilometre (2 mi) segment between Interstate 805 and California State Route 56. In Mississauga, Ontario, Highway 401 uses collector-express lanes for a total of 18 lanes through its intersection with Highway 403/Highway 410 and Highway 427.

These wide freeways may use separate collector and express lanes to separate through traffic from local traffic, or special high-occupancy vehicle lanes, either as a special restriction on the innermost lane or a separate roadway, to encourage carpooling. These HOV lanes, or roadways open to all traffic, can be reversible lanes, providing more capacity in the direction of heavy traffic, and reversing direction before traffic switches. Sometimes a collector/distributor road, a shorter version of a local lane, shifts weaving between closely spaced interchanges to a separate roadway or altogether eliminates it.

In some parts of the world, notably parts of the US, frontage roads form an integral part of the freeway system. These parallel surface roads provide a transition between high-speed "through" traffic and local traffic. Frequent slip-ramps provide access between the freeway and the frontage road, which in turn provides direct access to local roads and businesses.[19]

Except on some two-lane freeways (and very rarely on wider freeways), a median separates the opposite directions of traffic. This strip may be as simple as a grassy area, or may include a crash barrier such as a "Jersey barrier" or an "Ontario Tall Wall" to prevent head-on collisions.[20] On some freeways, the two carriageways are built on different alignments; this may be done to make use of available corridors in a mountainous area or to provide narrower corridors through dense urban areas.

Control of access

Control of access relates to a legal status which limits the types of vehicles that can use a highway, as well as a road design that limits the points at which they can access it.

Freeways are usually limited to motor vehicles of a minimum power or weight; signs may prohibit cyclists, pedestrians and equestrians and impose a minimum speed. It is possible for non-motorized traffic to use facilities within the same right-of-way, such as sidewalks constructed along freeway-standard bridges and multi-use paths next to freeways such as the Suncoast Trail along the Suncoast Parkway in Florida.

In some US jurisdictions, especially where freeways replace existing roads, non-motorized access on freeways is permitted. Different states of the United States have different laws. Cycling on freeways in Arizona may be prohibited only where there is an alternative route judged equal or better for cycling.[21] Wyoming, the least populated state, allows cycling on all freeways. Oregon allows bicycles except on specific urban freeways in Portland and Medford.[22]

In countries such as the United Kingdom new motorways require an Act of Parliament to ensure restricted right of way. Since upgrading an existing road (the "Queen's Highway") to a full motorway will result in extinguishing the right of access of certain groups such as pedestrians, cyclists and slow-moving traffic, many controlled access roads are not full motorways.[23] In some cases motorways are linked by short stretches of road where alternative rights of way are not practicable such as the Dartford Crossing (the furthest downstream public crossing of the River Thames) or where it was not economic to build a motorway alongside the existing road such as the former Cumberland Gap. The A1 is a good example of piece-wise upgrading to motorway standard—as of January 2013, the 639-kilometre-long (397 mi) route had five stretches of motorway (designated as A1(M)), reducing to four stretches in March 2018 with completion of the A1(M) through North Yorkshire.

Continental European non-motorway dual carriageways typically have limits set at 110–130 km/h (68–81 mph) for passenger cars.

Research shows 85 percent of motor vehicle-bicycle crashes follow turning or crossing at intersections.[24] Freeway travel eliminates almost all those conflicts save at entrance and exit ramps—which, at least on those freeways where cycling has not been banned, have sufficient room and sight for cyclists and motorists. An analysis of crashes in Arizona showed no safety problems with cycling on freeways. Fewer than one motor vehicle-bicycle crash a year was recorded on nearly 3,200 shoulder kilometres (2,000 mi) open to cyclists in Arizona.[25]

Major arterial roads will often have partial access control, meaning that side roads will intersect the main road at grade, instead of using interchanges, but driveways may not connect directly to the main road, and drivers must use intersecting roads to access adjacent land. At arterial junctions with relatively quiet side roads, traffic is controlled mainly by two-way stop signs which do not impose significant interruptions on traffic using the main highway. Roundabouts are often used at busier intersections in Europe because they help minimize interruptions in flow, while traffic signals that create greater interference with traffic are still preferred in North America. There may be occasional interchanges with other major arterial roads. Examples include US 23 between SR 15's eastern terminus and Delaware, Ohio, along with SR 15 between its eastern terminus and I-75, US 30, SR 29/US 33, and US 35 in western and central Ohio. This type of road is sometimes called an expressway.

Construction techniques

The most frequent way freeways are laid out is usually by building them from the ground up after things such as forestry or buildings are cleared away. Sometimes they deplete farmland, but other methods have been developed for economic, social and even environmental reasons.

Full freeways are sometimes made by converting at-grade expressways or by replacing at-grade intersections with overpasses; however, any at-grade intersection that ends a freeway remains. Often, when there is a two-lane undivided freeway or expressway, it is converted by constructing a twin corridor on the side by leaving a median between the two travel directions. The opposing side for the old two-way corridor becomes a passing lane.

Other techniques involve building a new carriageway on the side of a divided highway that has a lot of private access on one side and sometimes has long driveways on the other side since an easement for widening comes into place, especially in rural areas.

When a "third" carriageway is added, sometimes it can shift a directional carriageway by 50–200 feet (15–61 m) (or maybe more depending on land availability) as a way to retain private access on one side that favors over the other. Other methods involve constructing a service drive that shortens the long driveways (typically by less than 100 metres (330 ft)).

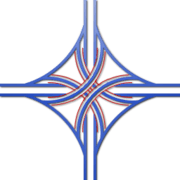

Interchanges and access points

An interchange or a junction is a highway layout that permits traffic from one controlled-access highway to access another and vice versa, whereas an access point is a highway layout where traffic from a distributor or local road can join a controlled-access highway. Some countries, such as the United Kingdom, do not distinguish between the two, but others make a distinction; for example, Germany uses the word Kreuz ("cross") for the former and Ausfahrt ("exit") for the latter. In all cases one road crosses the other via a bridge or a tunnel, as opposed to an at-grade crossing.

The inter-connecting roads, or slip-roads, which link the two roads, can follow any one of a number of patterns. The actual pattern is determined by a number of factors including local topology, traffic density, land cost, building costs, type of road, etc. In some jurisdictions feeder/distributor lanes are common, especially for cloverleaf interchanges; in others, such as the United Kingdom, where the roundabout interchange is common, feeder/distributor lanes are seldom seen.

A few of the more common types of junction are shown below:[26][27][28]

Motorways in Europe typically differ between exits and junctions. An exit leads out of the motorway system, whilst a junction is a crossing between motorways or a split/merge of two motorways. The motorway rules ends at exits, but not at junctions. At not so few bridges, motorways without changing appearance, temporarily ends between the two exits closest to the bridge (or tunnel), and continues as dual carriageways. This is in order to give slower vehicles a possibility to use the bridge. The Queen Elizabeth II Bridge / Dartford tunnel at London Orbital, is an example of this. London Oribital or the M25 is a motorway surrounding London, but at the last River Thames crossing before its mouth, motorway rules don't apply. (At this crossing the London Orbital is labeled A282 instead.)

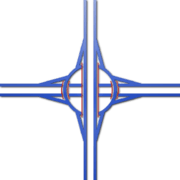

Four-level stack: used as a major junction, usually for freeway junctions

Four-level stack: used as a major junction, usually for freeway junctions Roundabout interchange: very common in the United Kingdom as either a junction or exit

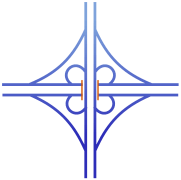

Roundabout interchange: very common in the United Kingdom as either a junction or exit Cloverleaf: used mainly as a junction

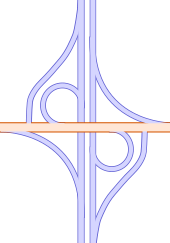

Cloverleaf: used mainly as a junction Parclo (partial cloverleaf) interchange: often used to link a minor road with a junction

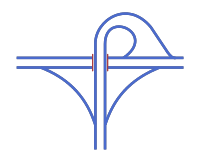

Parclo (partial cloverleaf) interchange: often used to link a minor road with a junction Trumpet interchange: a motorway "T" junction, used where the interchange represents the terminus of one of the two roads; also common on toll roads as it requires only one tollbooth

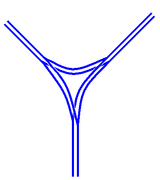

Trumpet interchange: a motorway "T" junction, used where the interchange represents the terminus of one of the two roads; also common on toll roads as it requires only one tollbooth Motorway split or merge. Basic logic resembles the T-junction

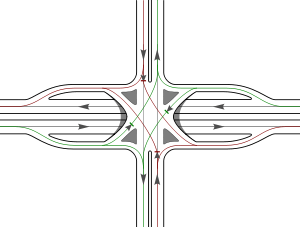

Motorway split or merge. Basic logic resembles the T-junction Single-point urban interchange, or SPUI; used in dense urban areas to reduce the land footprint of the junction.

Single-point urban interchange, or SPUI; used in dense urban areas to reduce the land footprint of the junction.

Safety

There are many differences between countries in their geography, economy, traffic growth, highway system size, degree of urbanization and motorization, etc.; all of which need to be taken into consideration when comparisons are made.[29] According to some EU papers, safety progress on motorways is the result of several changes, including infrastructure safety and road user behavior (speed or seat belt use), while others matters such as vehicle safety and mobility patterns have a not quantified impact.[30]

Motorways compared with other roads

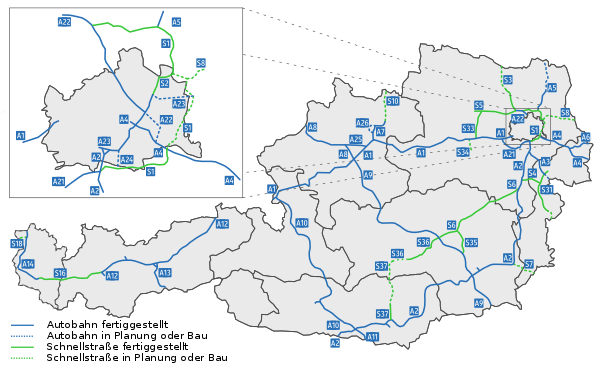

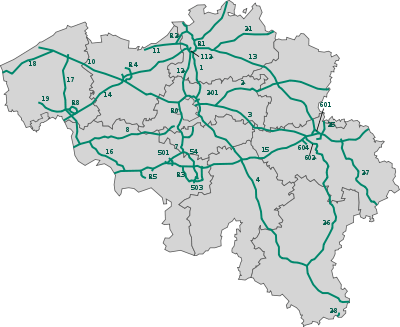

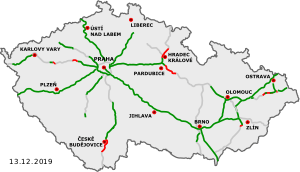

Motorways are the safest roads by design. While accounting for more than one quarter of all kilometres driven, they contributed only 8% of the total number of European road deaths in 2006.[31] Germany's Federal Highway Research Institute provided International Road Traffic and Accident Database (IRTAD) statistics for the year 2010, comparing overall fatality rates with motorway rates (regardless of traffic intensity):

| Country | All roads | Motorways |

|---|---|---|

| Austria | 7.32 | 2.15 |

| Belgium | 8.51 | 2.87 |

| Czech Republic | 16.22 | 3.38 |

| Denmark | 5.65 | 1.92 |

| Finland | 5.05 | 0.61 |

| France | 7.12 | 1.79 |

| Germany | 5.18 | 1.98 |

| Slovenia | 7.74 | 3.77 |

| Switzerland | 5.25 | 1.04 |

| United States | 6.87 | 3.62 |

| Sources:[32][33] | ||

The German autobahn network illustrates the safety trade-offs of controlled access highways. The injury crash rate is very low on autobahns[34] while 22 people died per 1000 injury crashes—although autobahns have a lower rate than the 29 deaths per 1,000 injury accidents on conventional rural roads, the rate is higher than the risk on urban roads. Speeds are higher on rural roads and autobahns than urban roads, increasing the severity potential of a crash.[35]

According to ESTC, German motorways without a speed limit, but with a 130 km/h (81 mph) speed recommendation, are three times more deadly than motorways with a speed limit.[36]

Germany also introduced some 130 km/h (81 mph) speed limits on various motorway sections which were not limited. This generated a reduction in deaths in a range from 20% to 50% on those sections.[37]

| Road class | Injury crashes | Fatalities | Injuries | Fatalities | Fatalities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| per 1,000,000,000 km travel | per 1000 injury crashes | ||||

| Autobahn | 17,847 | 387 | 80 | 1.7 | 21.7 |

| Urban | 206,696 | 1,062 | 1390 | 5.1 | 3.7 |

| Rural | 75,094 | 2,151 | 220 | 7.6 | 34.5 |

| Total | 299,637 | 3,600 | 420 | 5.0 | 12.0 |

Causes of accidents

Speed, in Europe, is considered to be one of the main contributory factors to collisions. Some countries, such as France and Switzerland, have achieved a death reduction by a better monitoring of speed. Tools used for monitoring speed might be increase in traffic density, improved speed enforcement and stricter regulation leading to driver license withdrawal, safety cameras, penalty point, and higher fines. Some other countries use automatic time over distance cameras (also known as section controls) to manage speed.[30]

Fatigue is considered as a risk factor more specific to monotonous roads such as motorways, although such data are not monitored/recorded in many countries.[30] According to Vinci Autoroutes one third of accidents in French motorways are due to sleepy driving.[38]

In French motorways, 23% of people killed on motorways were not wearing seat belts, while 98% of front-seat passengers and 87% of rear-seat passenger wear seat belts.[30]

Fatalities trends

Although safety results do not change much from year to year, in Europe some changes have been observed: motorways fatalities decreased by 41% during the 2006–2015 decade, but increased by 10% between 2014 and 2015. However, taking into account motorway network length to reflect exposure, data shows that fatalities per thousand kilometres halved between 2006 and 2015.[39]

| Year | Fatalities | Rate per million population |

Rate per 1,000 km of motorways |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 3,485 | 7.1 | 54.4 |

| 2010 | 2,329 | 4.7 | 32.9 |

| 2015 | 2,048 | 4.1 | 27.3 |

| Source: Traffic Safety Basic Facts 2017, Motorways[39] | |||

Toll effect

A University of Barcelona study suggests that if tolls are implemented on a controlled-access highway, drivers may seek alternative routes to avoid paying the tolls. This may result in a decrease of safety on roads which are not designed for heavy traffic.[40]

Safety in urban areas

In the United Kingdom, there are very few studies regarding the impact of road traffic accidents from existing and new urban motorways.[41] In particular, new urban motorways do not grant a reduction of traffic accidents.

In Italy, a study performed on urban motorway A56 Tangenziale di Napoli showed that reduction of speed leads to a decrease in accidents.[42]

In Marseille, France, from June 2009 to May 2010, CEREMA, the French centre for studies on risk, mobility and environment, performed a study on Marius, a network of urban motorways. This study established a link between accidents and traffic variables:[43]

- for single vehicle accidents, the 6-minute average speed on the fast lane; and the time headway (on every lane),

- for multiple vehicle accidents, the occupancy, and the time headway (for the middle lane).

The 150-kilometre-long (93 mi) Marius network counts 292 injury accidents or fatalities for 1.5 billion of vehicle-kilometres, that is 189 injury accidents or fatalities for 1 billion of vehicle-kilometres.

Some European countries have improved safety of urban motorways, with a set of to dynamically manage traffic flow in response to changing volumes, speeds, and incidentstechnics, including:

- variable speed limits, line control, and speed harmonization

- Shoulder running with emergency refuge areas

- Queue warning and variable messaging

- 24/7 monitoring of traffic with cameras and/or in-pavement sensors (both to detect incidents and identify when to reduce speed limits)

- Incident management

- Automated enforcement

- Specialized algorithms for temporary shoulder running, variable speed limits, and/or incident detection and management

- Ramp metering (coordinated or independent function)[44]

In 1994, it was assumed that lighting urban motorway would benefit from more safety than unlighted ones .[45]

In California, in 2001, a study has established, for urban freeways, some Relationships Among Urban Freeway Accidents, Traffic Flow, Weather and Lighting Conditions[46]

- it establishes a difference between dry freeways in daylight and wet freeways in darkness

- it establishes that left lane collisions are more likely induced by volume effects, while right lane collisions are more closely tied to speed variances in adjacent lanes (In California, people drive the right lane).

Environmental effects

Controlled-access highways have been constructed both between major cities as well as within them, leading to the sprawling suburban development found near most modern cities. Highways have been heavily criticized by environmentalists, urbanists, and preservationists for the noise,[47] pollution, and economic shifts they bring.[48] Additionally, they have been criticized by the driving public for the inefficiency with which they handle peak hour traffic.[49][50][51]

Often, rural highways open up vast areas to economic development and municipal services, generally raising property values. In contrast to this, above-grade highways in urban areas are often a source of lowered property values, contributing to urban decay. Even with overpasses and underpasses, neighbourhoods are divided—especially impoverished ones where residents are less likely to own a car, or to have the political and economic influence to resist construction efforts.[52] Beginning in the early 1970s, the US Congress identified freeways and other urban highways as responsible for most of the noise exposure of the US population.[53] Subsequently, computer models were developed to analyze freeway noise and aid in their design to help minimize noise exposure.[54]

Some cities have implemented freeway removal policies, under which freeways have been demolished and reclaimed as boulevards or parks, notably in Seoul (Cheonggyecheon), Portland (Harbor Drive), New York City (West Side Elevator Highway), Boston (Central Artery), San Francisco (Embarcadero Freeway) and Milwaukee (Park East Freeway).

An alternative to surface or above ground freeway construction has been the construction of underground urban freeways using tunnelling technologies. This has been particularly employed in the Australian cities of Sydney (which has five such freeways), Brisbane (which has three), and Melbourne (which has two). This has had the benefit of not creating heavily trafficked surface roads and, in the case of Melbourne's Eastlink Motorway, prevented the destruction of an ecologically sensitive area.

Other Australian cities face similar problems (lack of available land, cost of home acquisition, aesthetic problems and community opposition). Brisbane, which also has to contend with physical boundaries (the Brisbane River) and rapid population increases, has embraced underground freeways. There are currently three open to traffic (Clem Jones Tunnel (Clem7), Airport Link and Legacy Way) and one (East-West Link) is currently in planning. All of the tunnels are designed to act as an inner-city ring road or bypass system and include provision for public transport, whether underground or in reclaimed space on the surface.[55] However, freeways are not beneficial for road-based public transport services, because the restricted access to the roadway means that it is awkward for passengers to get to the limited number of boarding points unless they drive to them, largely defeating the purpose.[56]

In Canada, the extension of Highway 401 into Detroit, known as the Herb Gray Parkway, has been designed with numerous tunnels and underpasses that provide land for parks and recreational uses.

Freeway opponents have found that freeway expansion is often self-defeating: expansion simply generates more traffic. That is, even if traffic congestion is initially shifted from local streets to a new or widened freeway, people will begin to use their cars more and commute from more remote locations. Over time, the freeway and its environs become congested again as both the average number and distance of trips increases. This phenomenon is known as induced demand.[57][58]

Urban planning experts such as Drusilla Van Hengel, Joseph DiMento and Sherry Ryan argue that although properly designed and maintained freeways may be convenient and safe, at least in comparison to uncontrolled roads, they may not expand recreation, employment and education opportunities equally for different ethnic groups, or for people located in certain neighborhoods of any given city.[59] Still, they may open new markets to some small businesses.[60]

Construction of urban freeways for the US Interstate Highway System, which began in the late 1950s, led to the demolition of thousands of city blocks, and the dislocation of many more thousands of people. The citizens of many inner city areas responded with the freeway and expressway revolts. Through the study of Washington's response, it can be shown that the most effective changes came not from executive or legislative action, but instead from policy implementation. One of the foremost rationales for the creation of the United States Department of Transportation (USDOT) was that an agency was needed to mediate between the conflicting interests of interstates and cities. Initially, these policies came as regulation of the state highway departments. Over time, USDOT officials re-focused highway building from a national level to the local scale. With this shift of perspective came an encouragement for alternative transportation, and locally based planning agencies.[61]

At present, freeway expansion has largely stalled in the United States, due to a multitude of factors that converged in the 1970s: higher due process requirements prior to taking of private property, increasing land values, increasing costs for construction materials, local opposition to new freeways in urban cores, the passage of the National Environmental Policy Act (which imposed the requirement that each new federally funded project must have an environmental impact statement or report) and falling gas tax revenues as a result of the nature of the flat-cent tax (it is not automatically adjusted for inflation), the tax revolt movement,[62] and growing popular support for high-speed mass transit in lieu of new freeways.

Route numbering

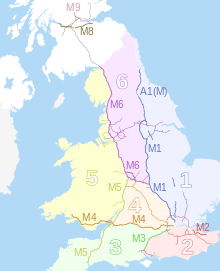

United Kingdom

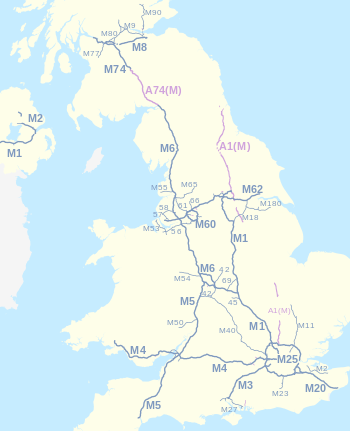

Great Britain

England and Wales

In England and Wales, the numbers of major motorways followed a numbering system separate to that of the A-road network, though based on the same principle of zones.[63] Running clockwise from the M1 the zones were defined for Zones 1 to 4 based on the proposed M2, M3 and M4 motorways. The M5 and M6 numbers were reserved for the other two planned long distance motorways.[64] The Preston Bypass, the UK's first motorway, should have been numbered A6(M) under the scheme decided upon, but it was decided to keep the number M6 as had already been applied.[64]

A map Showing Future Pattern of Principal National Routes was issued by the Ministry of War Transport in 1946 shortly before the law that allowed roads to be restricted to specified classes of vehicle (the Special Roads Act 1949) was passed. The first section of motorway, the M6 Preston Bypass, opened in 1958 followed by the first major section of motorway (the M1 between Crick and Berrygrove in Watford), which opened in 1959. From then until the 1980s, motorways opened at frequent intervals; by 1972 the first 1,600 kilometres (1,000 mi) of motorway had been built.

Whilst roads outside of urban areas continued to be built throughout the 1970s, opposition to urban routes became more pronounced. Most notably, plans by the Greater London Council for a series of ringways were cancelled following extensive road protests and a rise in costs. In 1986 the single-ring, M25 motorway was completed as a compromise. In 1996 the total length of motorways reached 3,200 kilometres (2,000 mi).

Motorways in Great Britain, as in numerous European countries, will nearly always have the following characteristics:

- No traffic lights (except occasionally on slip roads before reaching the main carriageway).

- Exit is nearly always via a numbered junction and slip road, with rare minor exceptions.

- Pedestrians, cyclists and vehicles below a specified engine size are banned.

- There is a central reservation separating traffic flowing in opposing directions. (The only exception to this is the A38(M) in Birmingham where the central reservation is replaced by another lane in which the direction of traffic changes depending on the time of day. There was another small spur motorway near Manchester with no solid central reservation, but this was declassified as a motorway in the 2000s.)

- No roundabouts on the main carriageway. This is only the case on motorways beginning with M (so called 'M' class). In the case of upgraded A roads with numbers ending with M (i.e. Ax(M)), roundabouts may exist on the main carriageway where they intersect 'M' class motorways. In all 'M' class motorways bar two, there are no roundabouts except at the point at which the motorway ends or the motorway designation ends. The only exceptions to this in Great Britain are:

- the M271 in Southampton which has a roundabout on the main carriageway where it meets the M27, but then continues as the M271 after the junction.

- on the M60. This came about as a result of renumbering sections of the M62 and M66 motorways near Manchester as the M60, to form a ring around the city. What was formerly the junction between the M62 and M66 now involves the clockwise M60 negotiating a roundabout, while traffic for the eastbound M62 and northbound M66 carries straight on from the M60. This junction, known as Simister Island, has also been criticised for the presence of a roundabout and the numbered route turning off.

- the A1(M) between the M62 in North Yorkshire and Washington in Tyne and Wear is built to full 'M' class standards without any roundabouts. It has been suggested that this section of the A1(M) should be reclassified as the northern extension of the M1.

It was proposed in 2013 that the Ax(M) format number would be used for the highest standard of a new classification of road referred to in England as "Expressways", which would be roads without normal roundabouts or right turns across the central reservation, and with graded junctions. Such roads would have motorway-style restrictions but emergency reservations rather than standard major motorway-standard hard shoulders.

Scotland

In Scotland, where the Scottish Office (superseded by the Scottish Executive in 1999) rather than the Ministry of Transport and Civil Aviation had the decision, there is no zonal pattern, but rather the A-road rule is strictly enforced. It was decided to reserve the numbers 7, 8 and 9 for Scotland.[65] The M8 follows the route of the A8, and the A90 became part of the M90 when the A90 was re-routed along the path of the A85.

Motorways follow an "M"-format, with two exceptions: the A823(M) near Rosyth joining the A823 to the M90 and the A74(M) between the English M6 at Gretna and the M74 at Abington.

Northern Ireland

In Northern Ireland a distinct numbering system is used, which is separate from the rest of the United Kingdom, though the classification of roads along the lines of A, B and C is universal throughout the UK and the Isle of Man. According to a written answer to a parliamentary question to the Northern Ireland Minister for Regional Development, there is no known reason as to how Northern Ireland's road numbering system was devised.[66] However motorways, as in the rest of the UK, are numbered M, with the two major motorways coming from Belfast being numbered M1 and M2. The M12 is a short spur of the M1 with the M22 being a short continuation (originally intended to be a spur) of the M2. There are two other motorways, the short M3, the M5 and a motorway section of the A8 road, known as the A8(M).

Republic of Ireland

In the Republic of Ireland, motorway and national road numbering is quite different from the UK convention. Since the passage of the Roads Act 1993, all motorways are part of, or form, national primary roads. These routes are numbered in series, (usually, radiating anti-clockwise from Dublin, starting with the N1/M1) using numbers from 1 to 33 (and, separately from the series, 50). Motorways use the number of the route of which they form part, with an M prefix rather than N for national road (or in theory, rather than R for regional road).[67] In most cases, the motorway has been built as a bypass of a road previously forming the national road (e.g. the M7 bypassing roads previously forming the N7)—the bypassed roads are reclassified as regional roads, although updated signposting may not be provided for some time, and adherence to signage colour conventions is lax (regional roads have black-on-white directional signage, national routes use white-on-green).

Under the previous legislation, the Local Government (Roads and Motorways) Act 1974, motorways theoretically existed independently to national roads, however the short sections of motorway opened during this act, except for the M50, always took their number from the national road that they were bypassing. The older road was not downgraded at this point (indeed, regional roads were not legislated for at this stage). Older signage at certain junctions on the M7 and M11 can be seen reflecting this earlier scheme, where for example N11 and M11 can be seen coexisting.

The M50, an entirely new national road, is an exception to the normal inheritance process, as it does not replace a road previously carrying an N number. The M50 was nevertheless legislated in 1994 as the N50 route (it had only a short section of non-motorway section from the Junction 11 Tallaght to Junction 12 Firhouse until its extension as the Southern Cross Motorway). The M50's designation was chosen as a recognisable number. As of 2010, the N34 is the next unused national primary road designation. In theory, a motorway in Ireland could form part of a regional road.[67]

Elsewhere

In Hungary, similar to Ireland, motorway numbers can be derived from the original national highway numbers (1–7), with an M prefix attached, e.g. M7 is on the route of the old Highway 7 from Budapest towards Lake Balaton and Croatia. New motorways not following the original Budapest-centred radial highway system get numbers M8, M9, etc., or M0 in the case of the ring road around Budapest.

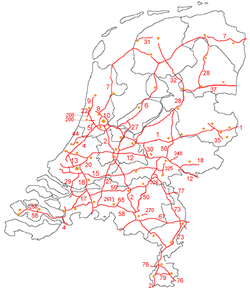

Also in the Netherlands, motorway numbers can be derived from the original national highway numbers, but with an A (Autosnelweg) prefix attached, like A9.

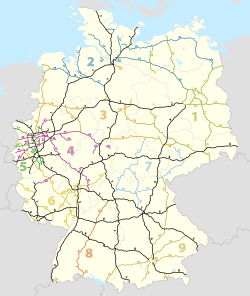

In Germany federal motorways have the prefix A (Autobahn). If the following number is an odd number the motorway generally follows a north–south direction, even-numbered motorways generally follow an east–west direction. Other controlled-access (dual carriageways) in Germany can be federal highways (Bundesstraßen), state highways (Landesstraßen), district highways (Kreisstraßen) and city highways (Stadtstraßen), each with their own numbering system.

In New Zealand, as well as in the Scandinavian countries, in Finland, Brazil and Russia, motorway numbers are also derived from the state highway route that they form a part of, but unlike Hungary and Ireland, they are not distinguished from non motorway sections of the same state highway route. In the cases where a new motorway acts as a bypass of a state highway route, the original state highway is either stripped of that status or renumbered. A low road number means a road suitable for long distance driving. In Switzerland as of April 2011, there are 1,763.6 kilometres (1,095.9 mi) of a planned 1,893.5 kilometres (1,176.6 mi) of motorway completed. The country is mountainous with a high proportion of tunnels, there are 220 totaling 200 kilometres (120 mi), which is over 12% of the total motorway length.[68]

In Australia, motorway numbering varies from state to state. Currently most states are adopting numbering systems with the prefix M for motorways.

In Belgium, motorways but also some dual carriageways have numbers preceded by an A. However, those that also have an E-number are generally referenced with that one. City ring and bypasses have numbers preceded by an R, these also can be either motorways or dual carriageways.

Regional variation

While the design characteristics listed above are generally applicable around the globe, every jurisdiction provides its own specifications and design criteria for controlled-access highways.

Africa

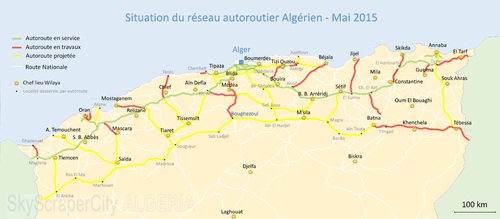

Algeria

In Algeria, motorway network has about 2,318 km (1,440 mi) in 2x3 lanes. The network is expanding increasingly, along with other kinds of infrastructure, though this is only true for the Northern region of the country, where most of its population lives. And this infrastructure is pretty well developed for North African standards.

For the moment, the entire Algerian motorway network is toll-free. The toll stations are being finalized and the launch of the motorway toll is scheduled for early 2021. The maximum speed authorized on the entire network is 120 km/h (75 mph).

.jpg) East–West Highway near Oran

East–West Highway near Oran- Est-West Motorway, near Ghomri, Relizane Province

Autoroute A2 près de Bouira

Autoroute A2 près de Bouira Autoroute Nord-Sud près de Médéa

Autoroute Nord-Sud près de Médéa

Egypt

Egypt has many multiple-lane, high-speed motorways. Two routes in the Trans-African Highway network originate in Cairo. Egypt also has multiple highway links with Asia through the Arab Mashreq International Road Network. Egypt has a developing motorway network, connecting Cairo with Alexandria and other cities. Though most of the transport in the country is still done on the national highways, motorways are becoming increasingly an option in road transport within the country. The existing motorways in the country are:

- Cairo–Alexandria Desert Road: It runs between Cairo and Alexandria, with an extension of 215 km (134 mi), it is the main motorway in Egypt.

- International Coastal Road: It runs from Alexandria to Port Said, along the Northern Nile Delta. It has a length of 280 km (170 mi). Also, amongst other cities, it connects Damietta and Baltim.

- Geish Road: It runs between Helwan and Asyut, along the Nile River, also connecting Beni Suef and Minya. Its length is 306 km (190 mi).

- Ring Road: It serves as an inner ring-road for Cairo. It has a length of 103 km (64 mi).

- Regional Ring Road: It serves as an outer ring road for Cairo, also connecting its suburbs like Helwan and 10th of Ramadan City. Its length is 130 km (81 mi).

Ethiopia

.jpg)

Much of Ethiopia’s Highway network is developing. Road projects now represent around a quarter of the annual infrastructure budget of the Ethiopian government. Additionally, through the Road Sector Development Program (RSDP), the government has earmarked $4 billion to construct, repair and upgrade roads over the next decade. Ethiopia has over 100,000 km (62,000 mi) of roads. In 2014, the Addis Ababa-Adama Expressway opened, becoming the first expressway in Ethiopia.

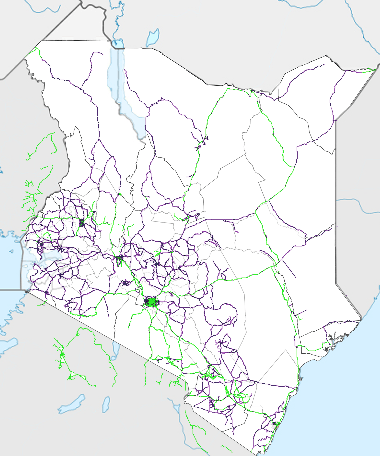

Kenya

The Kenya National Highways Authority is responsible for the maintenance, management, development, and rehabilitation of highways. According to the Kenya Roads Board, Kenya has 160,886 kilometres (99,970 mi) of roads. Two routes of the Trans-African Highway: the Cairo-Cape Town Highway and the Lagos-Mombasa highway. Roads in Kenya are divided into classes:

- Class S: "A Highway that connects two or more cities and carries safely a large volume of traffic at the highest speed of operation".

- Class A: "A Highway that forms a strategic route and corridor connecting international boundaries at identified immigration entry and exit points and international terminals such as international air or sea ports".

- Class B: "A Highway that forms an important national route linking national trading or economic hubs, County Headquarters and other nationally important centers to each other and to the National Capital or to Class A roads".

Morocco

The motorways and expressways of Morocco are a network of multiple-lane, high-speed, controlled-access highways in Morocco.

As of November 2016 the total length of Morocco's motorways is 1,785 km (1,109 mi) and 1,600 km (990 mi) expressways. Morocco plans to expand the road network. In the country 3,400 km (2,100 mi) of motorways and 2,100 km (1,300 mi) of expressways are currently under construction in different parts of the country.

In the year 2035 the total length of the motorways will be 5,185 km (3,222 mi) of motorways and 3,700 km (2,300 mi) of expressways. According to the minister of Morocco, this plan also includes a program specific to rural roads for the construction of 30,000 km (19,000 mi) of roads for an investment of 30 billion dirhams.

The first expressway in Morocco - A1 Casablanca-Rabat

The first expressway in Morocco - A1 Casablanca-Rabat Toll station at Bouznika

Toll station at Bouznika

Nigeria

Nigeria has the largest highway network in West Africa. Although much of the highways are poorly maintained, the Federal Roads Maintenance Agency have drastically improved them. Due to Nigeria’s strategic location, four routes of the Trans African Highway are situated in the country: the Trans-Sahara Highway to Algeria, the Trans-Sahelian Highway to Dakar, Senegal, the Trans-West African Coastal Highway and the Lagos-Mombasa Highway.

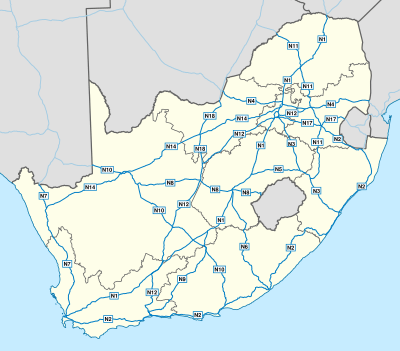

South Africa

In South Africa, the term freeway differs from most other parts of the world. A freeway is a road where certain restrictions apply.[71] The following are forbidden from using a freeway:

- a vehicle drawn by an animal;

- a pedal cycle (such as a bicycle);

- a motorcycle having an engine with a cylinder capacity not exceeding 50 cm3 or that is propelled by electrical power;

- a motor tricycle or motor quadrucycle;

- pedestrians

Drivers may not use hand signals on a freeway (except in emergencies) and the minimum speed on a freeway is 60 km/h (37 mph). Drivers in the rightmost lane of multi-carriageway freeways must move to the left if a faster vehicle approaches from behind to overtake.

Despite popular opinion that "freeway" means a road with at least two carriageways, single carriageway freeways exist, as is evidenced by the statement that "the roads include 1,400 km (870 mi) of dual carriageway freeway, 440 km (270 mi) of single carriageway freeway and 5,300 km (3,300 mi) of single carriage main road with unlimited access."[72]

Americas

Brazil

Although some 14,000 km (8,700 mi) of Brazilian highway[73] is built to motorway-standard, there is no distinct designation for controlled-access highways in the Brazilian federal and state highway systems. The term autoestrada (Portuguese for "motorway") is not commonly used in Brazil; the terms estrada ("road") and especially rodovia ("highway") are instead preferred. Nevertheless, the most technically advanced motorways in Brazil are defined Class 0 motorways by the National Department of Transport Infrastructure (DNIT). These motorways are built to safely allow for vehicular speeds of up to 130 km/h (81 mph)). In mountainous terrain, the maximum allowable gradient is 5% and minimum allowable radius of curvature is 665 m (2,182 ft) (with 12% super-elevation).

São Paulo state, with 5,000 km (3,100 mi) of motorway, has the most in the country. It is also the state with more highways conceded to the private sector.

Brazil's first motorway, the Rodovia Anhanguera, was completed in 1953 as an upgrade of the earlier single-carriageway highway. That same year, construction of the second carriageway of Rodovia Anchieta began. Motorway construction, most projects in the form of upgrades of older single-carriageway highways, quickened in the following decades. The current Class 0 motorways include: Rodovia dos Bandeirantes, Rodovia dos Imigrantes, Rodovia Castelo Branco, Rodovia Ayrton Senna/Carvalho Pinto, Rodovia Osvaldo Aranha (also known as "Free-way") and São Paulo's Metropolitan Beltway Rodoanel Mario Covas – all modern, post-1970s highways meeting modern European standards. Other stretches of highway such as the under-construction south BR-101 and Rodovia Régis Bittencourt are of older design standards.

The Rio–Niterói Bridge, officially part of the federal BR-101 highway. Also a landmark of Rio de Janeiro

The Rio–Niterói Bridge, officially part of the federal BR-101 highway. Also a landmark of Rio de Janeiro BR-116 in Ceará

BR-116 in Ceará

British overseas territories

A number of the United Kingdom's overseas territories have controlled-access highways, including the Turks and Caicos Islands and Cayman Islands.

Canada

.svg.png)

Canada has no current national system for controlled-access highways. All controlled-access freeways, including sections that form part of the Trans Canada Highway, are under provincial jurisdiction, and have no numeric continuation across provincial boundaries. The largest networks in the country are in Ontario (400-series highways) and Quebec (Autoroutes of Quebec). These roads are influenced by, and have influenced, US standards, but have design innovations and differences. The total length of dual-carriageways with controlled access in Canada is 6,350 km (3,950 mi), of which 564 km (350 mi) are in British Columbia, 642 km (399 mi) in Alberta, 59 km (37 mi) in Saskatchewan, 2,135 km (1,327 mi) in Ontario, 1,941 km (1,206 mi) in Quebec, and 1,000 km (620 mi) in the Maritimes.

El Salvador

The RN-21 (East–West, Boulevard Monseñor Romero), is the very first freeway to be built in El Salvador and in Central America. The freeway passes the northern area of the city of Santa Tecla, La Libertad. It has a small portion serving Antiguo Cuscatlán, La Libertad, and merges with the RN-5 (East–West, Boulevard de Los Proceres/Autopista del Aeropuerto) in San Salvador. The total length of the RN-21 is 9.35 km (5.81 mi) and is currently working as a traffic reliever in the metropolitan area. Although the RN-21 was to be named in honor of the first mayor of San Salvador, Diego de Holguín, due to political reasons it was renamed Boulevard Monseñor Romero, in honor of Óscar Romero. The first phase of the highway was completed in 2009, and the second phase was completed and opened in November 2012.

Mexico

Federal Highways (Spanish: Carretera Federal), are a series of highways that connect with roads from foreign countries; link two or more states of the Federation.

Mezcala Bridge on Highway 95 in Mexico

Mezcala Bridge on Highway 95 in Mexico Tehuantepec, Baja California

Tehuantepec, Baja California Mexican Federal Highway 1 Junction in San Ignacio, Baja California Sur

Mexican Federal Highway 1 Junction in San Ignacio, Baja California Sur Eastbound Fed. 2 just outside Altar, Sonora, after a summer rain

Eastbound Fed. 2 just outside Altar, Sonora, after a summer rain

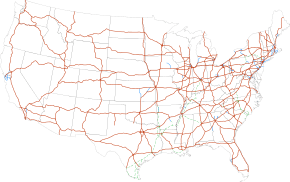

United States

In the United States, a freeway is defined by the US government's Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices as a divided highway with full control of access.[74] This means two things: first, adjoining property owners do not have a legal right of access,[75] meaning all existing driveways must be removed and access to adjacent private lands must be blocked with fences or walls; instead, frontage roads provide access to properties adjacent to a freeway in many places.

Second, traffic on a freeway is "free-flowing". All cross-traffic (and left-turning traffic) is relegated to overpasses or underpasses, so that there are no traffic conflicts on the main line of the highway, which must be regulated by traffic lights, stop signs, or other traffic control devices. Achieving such free flow requires the construction of many overpasses, underpasses, and ramp systems. The advantage of grade-separated interchanges is that freeway drivers can almost always maintain their speed at junctions since they do not need to yield to vehicles crossing perpendicular to mainline traffic.

In contrast, an expressway is defined as a divided highway with partial control of access.[76] Expressways may have driveways and at-grade intersections, though these are usually less numerous than on ordinary arterial roads.

This distinction was apparently first developed in 1949 by the Special Committee on Nomenclature of what is now the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials.[77] Prior to that distinction the first freeways were complete in 1940, the Pennsylvania Turnpike, and Arroyo Seco Parkway.[78] In turn, the definitions were incorporated into AASHTO's official standards book, the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices, which would become the national standards book of USDOT under a 1966 federal statute. The same distinction has also been codified into the statutory law of eight states: California,[79] Minnesota,[80] Mississippi,[81] Missouri,[82] Nebraska,[83] North Dakota,[84] Ohio,[85] and Wisconsin.[86]

However, each state codified the federal distinction slightly differently. California expressways do not necessarily have to be divided, though they must have at least partial access control. For both terms to apply, in Wisconsin, a divided highway must be at least four lanes wide; and in Missouri, both terms apply only to divided highways at least 16 km (10 mi) long that are not part of the Interstate Highway System. In North Dakota and Mississippi, expressways may have "full or partial" access control and "generally" have grade separations at intersections; a freeway is then defined as an expressway with full access control. Ohio's statute is similar, but instead of the vague word generally, it imposes a requirement that 50% of an expressway's intersections must be grade-separated for the term to apply.[87] Only Minnesota enacted the exact MUTCD definitions, in May 2008.

The term expressway is also used for what the federal government calls "freeways".[88] Where the terms are distinguished, freeways can be characterized as expressways upgraded to full access control, while not all expressways are freeways.

Examples in the United States of roads that are technically expressways (under the federal definition), but contain the word "freeway" in their names: State Fair Freeway in Kansas, Chino Valley Freeway in California, Rockaway Freeway in New York, and Shenango Valley Freeway (a portion of US 62) in Pennsylvania.

Unlike in some jurisdictions, not all freeways in the US are part of a single national freeway network (although together with non-freeways, they form the National Highway System). For example, many state highways such as California State Route 99 have significant freeway sections. Many sections of the older United States Numbered Highways network have been upgraded to freeways but have kept their existing US Highway numbers.

I-45 and I-10 next to Downtown Houston

I-45 and I-10 next to Downtown Houston Interstate 5 (I-5) in Los Angeles

Interstate 5 (I-5) in Los Angeles I-70 passes through Spotted Wolf Canyon at the eastern edge of the San Rafael Swell

I-70 passes through Spotted Wolf Canyon at the eastern edge of the San Rafael Swell- I-90 crossing Lake Washington

At the Big I in Albuquerque, New Mexico

At the Big I in Albuquerque, New Mexico.jpg) Aerial view of I-15 looking south from Sunset Road in the Las Vegas Valley

Aerial view of I-15 looking south from Sunset Road in the Las Vegas Valley Western end of I-10 at the McClure Tunnel in Santa Monica

Western end of I-10 at the McClure Tunnel in Santa Monica Interstate 91 with HOV lanes north of Hartford, Connecticut

Interstate 91 with HOV lanes north of Hartford, Connecticut

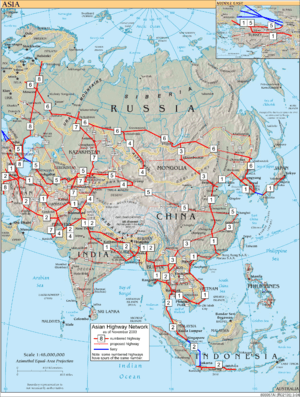

Asia

Afghanistan

Many highways of Afghanistan were built in the 1960s with American and Soviet assistance. The Soviets built a road and tunnel through the Salang pass in 1964, connecting northern and eastern Afghanistan. A highway connecting the principal cities of Herat, Kandahar, Ghazni, and Kabul with links to highways in neighboring Pakistan formed the primary highway. The historical Highway 1 currently connects the major cities. Afghanistan has over 42,000 km (26,000 mi) of roads, with 12,000 being paved. The highway infrastructure is currently going through reconstruction and can often be risky due to the instability of the country.

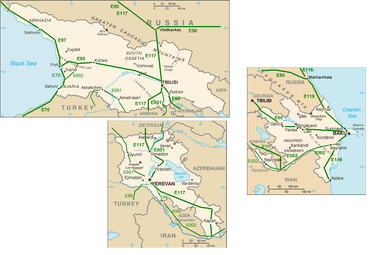

Armenia

Armenia has about 8,140 km (5,060 mi) of paved roads, of which 96% are asphalted. Armenia is connected to Europe through the International E-road network and Asia through the Asian Highway Network. Armenia is a member of the International Road Transport Union and the TIR Convention.

Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan has about 29,000 km (18,000 mi) of paved roads; the first paved roads were built during the Russian Empire. The road network, from rural roads to motorways, is today undergoing a rapid modernization with rehabilitations and extensions. For every 1,000 km2 (390 sq mi) of national territory, there are 334 km (208 mi) of roads. Azerbaijan is connected to Europe through the International E-road network and Asia through the Asian Highway Network.

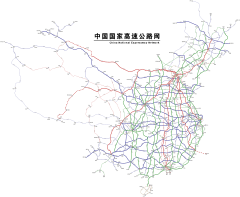

China

The expressway network of China, with the national-level expressway system officially known as the National Trunk Highway System (Chinese: 中国国家干线公路系统; pinyin: Zhōngguó Guójiā Gànxiàn Gōnglù Xìtǒng; abbreviated as NTHS), is an integrated system of national and provincial-level expressways in China.[89][90]

By the end of 2018, the total length of China's expressway network reached 142,500 km (88,500 mi),[91] the world's largest expressway system by length, having surpassed the overall length of the American Interstate Highway System in 2011.[92] Planned length is 168,478 km (104,687 mi) by 2020.[93]

Expressways in China are a fairly recent addition to a complicated network of roads. According to Chinese government sources, China did not have any expressways before 1988.[94] One of the earliest expressways nationwide was the Jingshi Expressway between Beijing and Shijiazhuang in Hebei province. This expressway now forms part of the Jingzhu Expressway, currently one of the longest expressways nationwide at over 2,000 km (1,200 mi).

The expressway crosses the Yangtze River over the Jiangyin Suspension Bridge

The expressway crosses the Yangtze River over the Jiangyin Suspension Bridge G106, Jingkai Expressway section in southern Beijing

G106, Jingkai Expressway section in southern Beijing G6 Expressway at the interchange with the Fifth Ring Road in northern Beijing

G6 Expressway at the interchange with the Fifth Ring Road in northern Beijing Signs using the new numbering system as seen on China National Expressway 1 in Tianjin

Signs using the new numbering system as seen on China National Expressway 1 in Tianjin

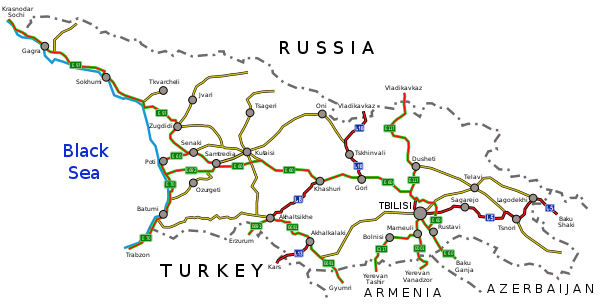

Georgia

The road network in Georgia consists of 1,603 km (996 mi) of main or international highways that are considered to be in good condition and some 18,821 km (11,695 mi) of secondary and local roads that are, generally, in poor condition, although the conditions are improving. Only 7,854 km (4,880 mi) out of over 20,000 km (12,000 mi) of Georgian roads are paved. Georgia is connected to Europe via he International E-road network and Asia through the Asian Highway Network.

Hong Kong

In Hong Kong major motorways are numbered from 1 to 10 in addition to their names. Speed limits on expressways typically range from 70 to 110 km/h (43 to 68 mph).

North Lantau Highway on Lantau Island

North Lantau Highway on Lantau Island.jpg) Tolo Highway in Ma Liu Shui

Tolo Highway in Ma Liu Shui Fanling Highway in Sheung Shui

Fanling Highway in Sheung Shui North West Tsing Yi Interchange near Tsing Ma Bridge (Lantau Link)

North West Tsing Yi Interchange near Tsing Ma Bridge (Lantau Link)

India

Expressways (known as "Gatimarg/गतिमार्ग", or "Speedways" in Hindi and other Indian languages) are the highest class of roads in India's road network and make up around 1,642 km (1,020 mi) of the National Highway System. They have a minimum of six or eight-lane controlled-access highways where entrance and exit is controlled by the use of slip roads. The Expressways are operated and maintained by the Union, through the National Highways Authority of India.

Section of the Delhi Gurgaon Expressway

Section of the Delhi Gurgaon Expressway The Mumbai-Pune Expressway as seen from atop the Sahyadris

The Mumbai-Pune Expressway as seen from atop the Sahyadris The Mumbai-Pune Expressway

The Mumbai-Pune Expressway.jpg) A section of Delhi–Noida Direct Flyway

A section of Delhi–Noida Direct Flyway

Indonesia

In Indonesia, an expressway or highway is better known as a toll road (Indonesian: Jalan Tol, or known as Jalan Bebas Hambatan). Indonesia has 1,710 km (1,060 mi) expressway length so far, almost 70% of its expressways are in Java island.

In 2009, the Indonesian government had planned to expand more expressway network in Java island by connecting Merak to Banyuwangi which is the total length of Trans-Java toll road including large cities expressway in Java such as Jakarta, Surabaya, Bandung and its complements is more than 1,000 km (620 mi). The Indonesian government also had planned to build the Trans-Sumatra toll road which connects Banda Aceh to Bakauheni spanning 2,700 km (1,700 mi). In 2012, the government allocated 150 trillion rupiah for the construction of the toll roads. There are three stages of construction of Trans-Sumatra toll road which is expected to be connected together in 2025.[95] The other islands in Indonesia such as Kalimantan, Sulawesi also has begun constructed its expressways including connecting Manado to Makassar in Sulawesi and also Pontianak to Balikpapan in Kalimantan.[96] However, there are still no plans to build an expressway in Western New Guinea due to its slow population growth. Indonesia is expected to have at least 7,000 km (4,300 mi) of expressway in 2030.

Indonesia doesn't acknowledge or observe any highway numbering yet.

Iran

The history of freeways in Iran goes back to before the Iranian Revolution. The first freeway in Iran was built at that time, between Tehran and Karaj with additional construction and the studies of many other freeways started as well. Today Iran has about 2,160 km (1,340 mi) of freeway.

Iraq

Iraq’s network of highways connects it from the inside to neighboring countries such as Syria, Turkey, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Jordan and Iran. When Saddam Hussein visited the United States, he was impressed at the highway style and ordered the highways to be built in American form. Freeway 1 is the longest freeway in the country, connecting from Umm Qasr Port in Basra to Ar Rutba in Anbar, spreading to a new freeway connecting it to Syria and Jordan. Iraq has about 45,550 km (28,300 mi) of highways, with 38,400 km (23,900 mi) of them paved.

Israel

Controlled-access highways in Israel are designated by a blue colour. Blue highways are completely grade-separated but may include bus stops and other elements that may slow down traffic on the right lane.

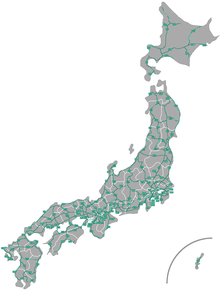

Japan

National expressways (高速自動車国道, Kōsoku Jidōsha Kokudō), generally known as 高速道路 (Kōsoku Dōro), make up the majority of controlled-access highways in Japan. The network boasts an uninterrupted link between Aomori Prefecture at the northern part of Honshū and Kagoshima Prefecture at the southern part of Kyūshū, linking Shikoku as well. Additional expressways serve travellers in Hokkaidō and on Okinawa Island, although those are not connected to the Honshū-Kyūshū-Shikoku grid. Expressways have a combined length of 9,341 km (5,804 mi) as of April 2017.[97][98][99]

Many Japanese expressways go through the steep mountains

Many Japanese expressways go through the steep mountains A group of green-colored directional signs on a Japanese expressway

A group of green-colored directional signs on a Japanese expressway- Toll gates are placed at most of the entrances and exits of Japanese expressways

Aerial view of Toyota Junction, connecting Tomei Expressway and Ise-Wangan Expressway

Aerial view of Toyota Junction, connecting Tomei Expressway and Ise-Wangan Expressway The Shutoko C1 route forms a loop of the center of Tokyo

The Shutoko C1 route forms a loop of the center of Tokyo

South Korea

Since Gyeongin Expressway linking Seoul and Incheon opened in 1968, national expressway system in South Korea has been expanded into 36 routes, with total length of 4,481 km (2,784 mi) as of 2017. Most of expressways are four-lane roads, while 1,030 km (640 mi) (26%) have six to ten lanes. Speed limit is typically 100 km/h (62 mph) for routes with four or more lanes, while some sections having fewer curves have limit of 110 km/h (68 mph).

Expressways in South Korea were originally numbered in order of construction. Since 24 August 2001, they have been numbered in a scheme somewhat similar to that of the Interstate Highway System in the United States. Furthermore, the symbols of the South Korean highways are similar to the US red, white and blue.

- Arterial routes are designated by two-digit numbers, with north–south routes having odd numbers, and east–west routes having even numbers. Primary routes (i.e. major thoroughfares) have 5 or 0 as their last digit, while secondary routes end in other digits.

- Branch routes have three-digit route numbers, where the first two digits match the route number of an arterial route. This differs from the American system, whose last two digits match the primary route.

- Belt lines have three-digit route numbers where the first digit matches the respective city's postal code. This also differs from American numbering.

- Route numbers in the range 70–99 are not used in South Korea; they are reserved for designations in the event of Korean reunification.

- The Gyeongbu Expressway kept its Route 1 designation, as it is South Korea's first and most important expressway.

Approaching Seoul from Incheon Airport

Approaching Seoul from Incheon Airport

Airport Town Square junction

Airport Town Square junction Incheon Bridge Toll Gate

Incheon Bridge Toll Gate

Malaysia

Controlled-access highways in Malaysia are known as expressways (Malay: lebuhraya – this is also the name for highways). However, some expressways, particularly bridges and tunnels such as the Penang Bridge, do not formally use the expressway name; a small number confusingly use the term highway, which is normally the designation for limited-access roads. Route numbers of designated expressways begin with the letter E. All expressways (excluding a section of the South Klang Valley Expressway, which is a two-lane expressway) are built with dual carriageways and at least two lanes in each direction; urban expressways generally have three or more lanes in each direction.

While all expressways are grade separated at major roadways, many urban expressways in the Greater Kuala Lumpur region often have at-grade intersections, including with residential roads and shopfronts, thus do not meet the strict definition of a controlled-access highway. These expressways were previously normal arterial or collector roads that had such intersections, and were not removed when the roads were converted to expressways due to the resulting accessibility and sometimes political issues. Despite this, no expressway allows traffic to cross the median strip (apart from U-turns on a limited number of expressways) and expressways do not have at-grade traffic signals or roundabouts. Expressways have a maximum speed limit of 110 km/h (68 mph), while speed limits of 90 km/h (56 mph) or lower are typical in built-up areas.

As of 2020, expressways have only been designated in Peninsular Malaysia. There are 34 fully or partially open expressways with an approximate total length of 1,821 km (1,132 mi).[100][101] The vast majority of expressways are tolled; the North–South Expressway network, East Coast Expressway and West Coast Expressway predominantly use the ticket system of toll collection, while all other expressways use the barrier system. The construction and operation of expressways in Malaysia are usually privatised via concession agreements with the federal government, using the build–operate–transfer system.

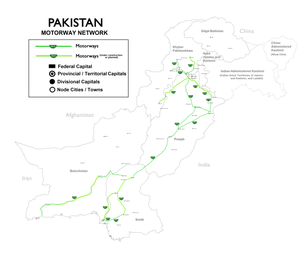

Pakistan

The motorways of Pakistan and expressways of Pakistan are a network of multiple-lane, high-speed, limited-access or controlled-access highways in Pakistan, which are owned, maintained and operated federally by Pakistan's National Highway Authority. The total length of Pakistan's motorways and expressways is 1,670 km (1,040 mi) as of November 2016. Around 3,690 km (2,290 mi) of motorways are currently under construction in different parts of the country. Most of these motorway projects will be complete between 2018 and 2020.

Pakistan's motorways are part of Pakistan's National Trade Corridor project that aims to link Pakistan's three Arabian Sea ports of Karachi, Port Qasim and Gwadar to the rest of the country. These would further link with Central Asia and China, as proposed in the China Pakistan Economic Corridor.

Pakistan's first motorway, the M2, was inaugurated in November 1997; it is a 367-kilometre-long (228 mi), six-lane motorway that links Pakistan's federal capital, Islamabad, with Punjab's provincial capital, Lahore. Other completed motorways and expressways are M1 Peshawar–Islamabad Motorway, M4 PindiBhattian–Faislabad-Multan Motorway, E75 Islamabad-Murree–Kashmir Expressway, M3 Lahore–Multan Motorway, M8 Ratadero–Gawader Motorway, E8 Islamabad Expressway, M5 Multan-Sukkur Motorway, M9 Karachi-Hyderabad, Sindh and few others.

The motorway M2 passes through the Salt Range mountains

The motorway M2 passes through the Salt Range mountains M1 motorway westbound towards Peshawar

M1 motorway westbound towards Peshawar M1 Peshawar Toll Plaza

M1 Peshawar Toll Plaza

Philippines

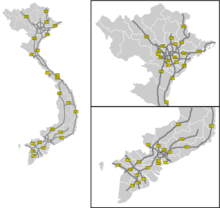

.svg.png)

Full control-access highways in the Philippines are referred to as expressways, which are usually toll roads. The expressway network is concentrated in Luzon, with the North Luzon Expressway and South Luzon Expressway being the most important ones. The expressway network in Luzon do not form a network, but there are ongoing construction to interconnect those highways as well as to decongest the existing roads in the areas they serve. Expressways are being introduced to Visayas and Mindanao through the construction of the Cebu–Cordova Link Expressway in Metro Cebu and Davao City Expressway in Davao City.

Saudi Arabia

Highways in Saudi Arabia vary from eight-laned roads to small two-lane roads in rural areas. The city highways and other major highways are well maintained, especially the roads in the capital Riyadh. The roads have been constructed to resist the consistently high temperatures and do not reflect the strong sunshine. The other city highways such as the one linking coast to coast are not as great as the inner-city highways but the government is now working on rebuilding those roads. Saudi Arabia is part of the Arab-Mashreq Highway Network and connects to the rest of Asia through the Asian Highway Network.