Hyderabad, Sindh

Hyderabad (Sindhi and Urdu: حيدرآباد; (/ˈhɛdərəbɑːd/ (![]()

Hyderabad حیدر آباد | |

|---|---|

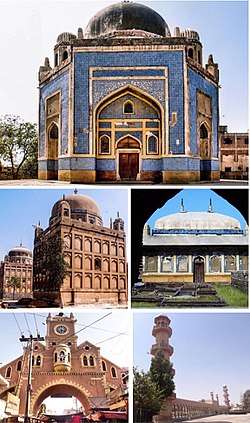

Clockwise from top: Tomb of Mian Ghulam Kalhoro, Tomb of a Talpur Mir, Rani Bagh, Navalrai Market Clocktower, Tombs of Talpur Mirs | |

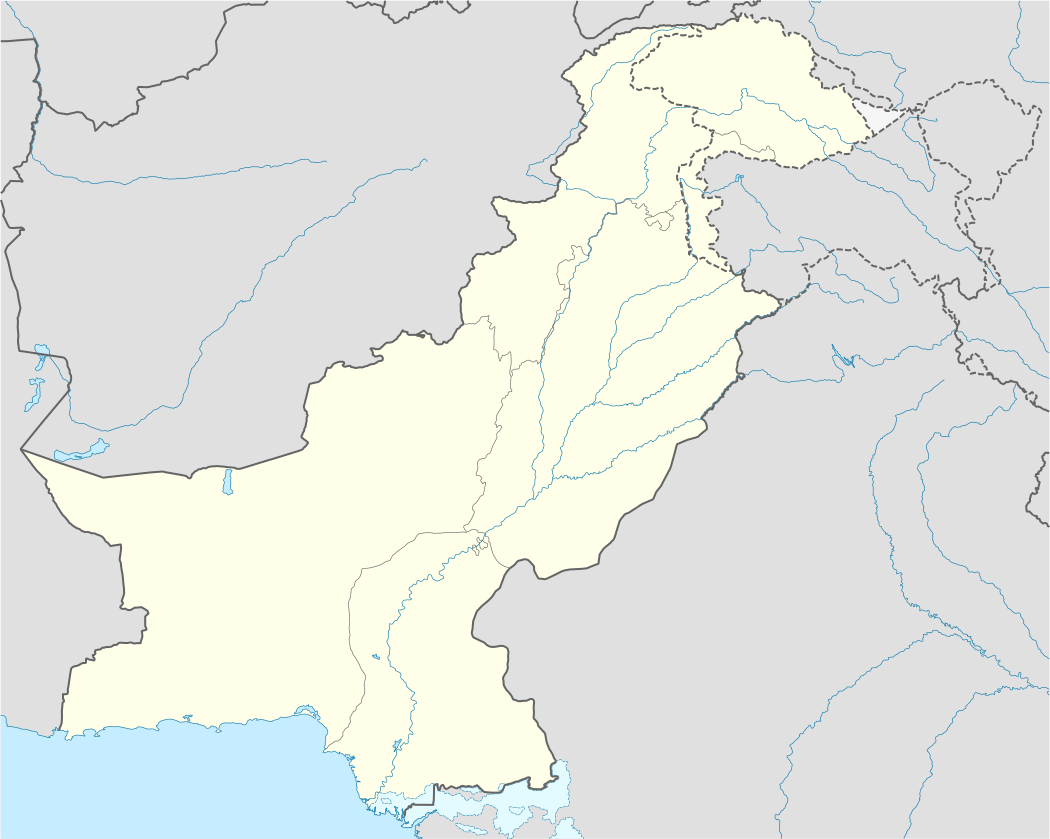

Hyderabad Location in Pakistan  Hyderabad Hyderabad (Pakistan) | |

| Coordinates: 25°22′45″N 68°22′06″E | |

| Country | |

| Province | |

| Division | Hyderabad |

| District | Hyderabad |

| Autonomous towns | 5 |

| Number of Union councils | 20 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Municipal Corporation |

| • Mayor | Tayyab Hussain |

| • Deputy Mayor | Syed Suhail Mehmood Mashadi |

| Area | |

| • City | 292 km2 (113 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 1,740 km2 (670 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 13 m (43 ft) |

| Population (2017)[2] | |

| • City | 1,732,693 |

| • Rank | 8th, Pakistan |

| • Density | 5,900/km2 (15,000/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 2,199,463[3] |

| Demonym(s) | Hyderabadi |

| Time zone | UTC+5 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+6 (PDT) |

| Area code(s) | 02 |

| HDI (2017) | |

| Website | N/A |

Toponymy

The city was named in honour of Ali,[6] the fourth caliph and cousin of the Prophet Muhammad. Hyderabad's name translates literally as "Lion City" - from haydar, meaning "lion," and ābād, which is a suffix indicating a settlement. "Lion" references Ali's valour in battle,[7] and so he is often referred to as Ali Haydar, roughly meaning "Ali the Lionheart," by South Asian Muslims.

History

Founding

The River Indus was changing course around 1757, resulting in periodic floods of the then capital of the Kalhora dynasty, Khudabad. Mian Ghulam Shah Kalhoro decided to shift the capital away from Khudabad, and founded Hyderabad in 1768 over a limestone ridge on the eastern bank of the Indus River known as Ganjo Takkar, or "Bald Hill." The small hill is traditionally believed to have been the location of the ancient settlement of Neroon Kot, a town which had fallen to the armies of Muhammad Bin Qasim in 711 CE.[8][9] When the foundations were laid, the city came to be known by the nickname Heart of the Mehran.

Devotees of Imam Ali advised Mian Ghulam Shah Kalhoro to name the city in honour of their Imam.[9] The Shah of Iran later gifted the city a stone which purportedly bears the imprint of Ali's feet.[9] The stone was placed in the Qadamgah Maula Ali, which then became a place of pilgrimage.[9]

Kalhora

In 1768, Mian Ghulam Shah Kalhoro ordered a fort to be built on one of the three hills of Hyderabad to house and defend his people. The fort was built using baked clay bricks, earning it the name Pacco Qillo, meaning Strong Fort in Sindhi.[10] The fort was completed in 1769, and is spread over 36 acres.[9] Mian Ghulam Shah also built the "Shah Makki Fort," commonly known as Kacha Qila, to fortify the tomb of the Sufi saint Shah Makki.[11]

Hyderabad remained the Kalhora capital during the period in which Sindh was united under their rule. Attracted by the security of the city, Hyderabad began to attract artisans and traders from throughout Sindh, thereby resulting in the decline of other rival trading centres such as Khudabad.[9] A portion of the population of Khudabad migrated to the new capital, including Sonaras, Amils and Bhaibands. Those groups retained the term "Khudabadi" in the names of their communities as a marker of origin.

Mian Ghulam Shah died in 1772, and was succeeded by his son, Sarfraz Khan Kalhoro. In 1774, Sarfraz Khan built a "New" Khudabad north of Hala in memory of the old Kalhoro capital, and attempted to shift his capital there.[9] The attempt failed, and Hyderabad continued to prosper while New Khudabad was abandoned by 1814.[9] A formal plan for the city was laid out by Sarfraz Khan in 1782.[8]

Talpur

Mir Fateh Ali Khan Talpur captured the city of Khudabad from the Kalhoros in 1773, and made the city his capital. He then captured Hyderabad in 1775,[9] and shifted his capital there in 1789 after Khudabad once again flooded. Renovation and reconstruction of the city's fort began in 1789, and lasted for 3 years.[9] Celebrations were held in 1792 to mark his formal entry in the Pacco Qillo fort,[9] which he made his residence and held court.

Talpur rule maintained Hyderabad's security, and the city continued to attract migrants from throughout Sindh, turning the city into a major regional center. Lohana Hindus from Afghanistan migrated to the city and set up ship as metalworkers.[9] The city's goldsmiths, silversmiths, and leather tanners began to export their Hyderabadi wares abroad.[9] The city's textile industry boomed with the arrival of Susi and Khes cotton cloth and handicrafts from towns in rural Sindh.[9] The city's became renowned for its calligraphers and bookbinders, while its carpet dealers traded carpets from nearby Thatta.[9]

Henry Pottinger traveled up the Indus River in the early 1830s on behalf of the British.[12] He claimed to have seen 341 ships over the course of 19 days at Hyderabad, indicating its importance as a major trading center by this time.[9] Hyderabad's goods were mostly exported to markets in Khorasan, India, Turkestan, and Kashmir - though some Hyderabadi wares were displayed at The Great Exhibition of 1851 in London.[9]

In order to use the Indus River for commercial navigation to Punjab, the British signed a treaty with the rulers of Hyderabad and Khairpur that guaranteed the British free passage along the Indus and through Sindh.[12] Mir Murad Ali was pressured into accepting an 1838 treaty which resulted in the stationing of a British Resident in the city.[12] The British also signed a treaty of "eternal friendship" with the Talpur rulers of Hyderabad in the early 19th century, who promised not to allow the French to set up residency in Sindh.[12] In 1839, they were pressured into forcing another treaty that guaranteed the British trade and security privileges.[12]

British

The British defeated the city's Talpur rulers at the Battle of Hyderabad on 24 March 1843. The provincial capital was then transferred to Karachi by the British general Sir Charles Napier. Being the last stronghold in Sindh, the conquered city was the final step in the British Conquest of Sindh.[13] Following the success of the British, several of the city's Talpur Mirs rulers were exiled and died in Calcutta. Their bodies were eventually brought back to Hyderabad, and were buried in the Tombs of the Talpur Mirs located at the northern edge of the Ganjo Hill.[8]

Hyderabad's prosperity did not initially decline after the shifting of Sindh's capital to Karachi. Merchants there forged links with the commercial community in Hyderabad, and began exporting Hyderabadi wares to distant markets.[9] Following Sindhi's assimilation into the Bombay Presidency in 1847, the city emerged as hub for a style of handicrafts known as Sindwork that was peddled in Bombay, and prized by its European residents for its perceived authenticity of style.[14] The work was then shipped from Bombay to Egypt in order to be sold as souvenirs to tourists there.[14] Hyderabadi traders also spread east towards Singapore and Japan as well.[14] Unable to fulfill demand for its products, Hyderabad's traders began to import crafts from Kashmir, Varanasi, China, and Japan to ease demand.[14] Sindwork handicrafts thus placed Hyderabad at the center of a new trading network that was almost entirely dominated by Hindus from the city's mercantile Bhaiband segment of the Lohana caste,[14] although the artisans themselves were primarily Muslim.[15]

The city's jail was built in 1851,[9] and the Municipality of Hyderabad was established in 1853.[13] In the Pacco Qillo the British kept the arsenal of the province, transferred from Karachi in 1861, and the palaces of the ex-Amirs of Sind that they had taken over. In 1857, when the Indian mutiny raged across the South Asia, the British held most of their regiments and ammunition in this city. Though the city did not witness major fighting, the British demolished the large round tower that once stood outside of Pacco Qillo, deeming it a potential risk to their rule were it to fall into the hands of rebels.[9]

Hyderabad's Rani Bagh ("Queen's Garden") was established as Das Gardens in 1861, and was re-christened in honour of Queen Victoria.[9] British-style schools were introduced in Hyderabad by the 1860s, while the St Joseph Missionary School was established in 1868.[9] Further European schools were opened, while Hyderabad's Hindu and Muslim elite established schools for their respective communities throughout the British colonial period.[9] A hospital, psychiatric institution, and quarters for officials were built in 1871.[9] By 1872, 43,088 people lived in the city.[13] The city by 1873 had 20 kilometers of metaled roads that were lit at night by kerosene lamps.[9] The newly built urban quarters of Saddar and Soldier Bazaar further expanded the city.

The British built a rail network throughout the western part of South Asia in the 1880s, and purchased the private Scinde Railway to connect the province to Kabul trade routes. The rail network would later be called the North-Western State Railway. The Kotri Bridge was completed in 1900 to traverse the Indus, and link Hyderabad to Karachi.[9] Hyderabad's economy grew as a result of improved transportation. The city increasingly developed into a consumer market under British rule, and the city's exports began to decline, though increased transit trade allowed the city's economy to continue growing.[9]

In 1901, 69,378 people lived in the city. Hinduism was the most dominant religion with 43,499 followers, while 24,831 Muslims made up the largest religious minority. The city ranked seventh in the Bombay Presidency in terms of population.[13] By 1907, the Gazetteer of Sindh claimed that 5,000 Hyderabadi merchants were to be found dispersed throughout the world.[14] The city's Navalrai Clock Tower was built in 1914.[16] Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore remarked in the early 20th century that Hyderabad was the "most fashionable" city in all of India.[17]

Modern

The City of Hyderabad served as the capital of Sindh province between 1947 and 1955. The Partition of British India resulted in the large-scale exodus of much of the city's Hindu population, though like much of Sindh, Hyderabad did not experience the widespread rioting that occurred in Punjab and Bengal.[18] In all, less than 500 Hindu were killed in Sindh between 1947-48 as Sindhi Muslims largely resisted calls to turn against their Hindu neighbours.[19] Hindus did not flee Hyderabad en masse until riots erupted in Karachi on 6 January 1948, which sowed fear in Sindhi Hindus despite the fact that the riots were local and regarded Sikh refugees from Punjab seeking refuge in Karachi.[18]

The Hindus who departed had played a major role in the city's economy, and formed the majority of the Hyderabad's population.[14] The vacuum left by the departure of much of the city's Hindu population was quickly filled by newly arrived refugees from India, known as Muhajirs.[20] By 1951, 66% of the city was made up of Muhajirs.[21] Though Hyderabad became a majority Urdu-speaking city in the 1940s, the arrival of Pashtuns and Punjabis from northern Pakistan further diversified the city's ethnic composition over the next few decades.[20]

Animosity between Urdu and Sindhi speakers first arose in 1967,[9] it intensified under the Pakistan People's Party government in the 1970s, which were widely perceived by Muhajirs to be a pro-Sindhi administration.[22] Violence erupted between Urdu and Sindhi speakers during riots in 1971 when the provincial government wished to impose Sindhi-language requirements on Urdu speakers, and again in 1972 in reaction to the 1972 Sindhi Language Bill.[22]

The Khuda Ki Basti housing scheme was launched in Hyderabad 1981 as a way to provide housing to low-income residents by forming local cooperatives pool funds to gradually provide increased services that would in turn be managed by community members.[23] Success of the project resulted in the programme being launched in Karachi as well.

The late 1980s saw turbulent ethnic rioting between Sindhis and Muhajirs.[24] On 30 September 1988, militants from the Sindh Progressive Party drove into Muhajir dominated areas in the city, and opened indiscriminate fire in busy crossroads.[22] The so-called "Hyderabad Massacre" resulted in the deaths of over 60 people in a single day, and more than 250 deaths in total. In a backlash, more than 60 Sindhi speaking people were gunned down in Karachi.[24][25] The city began to divide itself ethnically, and the Muhajir population migrated en masse from Qasimabad and the interior of Sindh into Latifabad. Similarly, Sindhis moved to Qasimabad from Hyderabad and Latifabad.[24][26][27] Further ethnic disturbances occurred in May 1990, including a police-led siege of the Pacco Qillo fortress in the center of Hyderabad,[22] in which Muhajir activists claim 150 were killed.[28] 2 bombings on trains in Hyderabad killed 10 people in 2000.[29]

Much of Hyderabad's public spaces have been encroached upon by illegally-constructed homes and businesses.[9] Much of the city's historic structures are badly neglected,[9] with little preservation being undertaken by the provincial administration.

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1941 | 135,000 | — |

| 1951 | 242,000 | +79.3% |

| 1961 | 435,000 | +79.8% |

| 1972 | 629,000 | +44.6% |

| 1981 | 752,000 | +19.6% |

| 1998 | 1,166,894 | +55.2% |

| 2017 | 1,732,693 | +48.5% |

| Source: [30][31] | ||

Population

Hyderabad is home to 1,732,693 people as per the 2017 Census of Pakistan.[32] The city gained 565,799 residents since the 1998 Census, representing an increase of 48.5% - the lowest growth rate of the ten largest Pakistani cities.[33]

Ethnicity

Hyderabad was a majority Sindhi Hindu city prior to 1948,[14] when many migrated to India and elsewhere[34] after the independence of Pakistan 1947. Hindus who departed had played a major role in the city's economy, and formed the majority of the Hyderabad's population.[14] The vacuum left by the departure of much of the city's Hindu population was quickly filled by the newly arrived Urdu speaking Muslim refugees from India, known as Muhajirs.[20]

Following the arrival of Muhajirs, Hyderabad became a majority Urdu-speaking city, with Muhajirs making up 66% of the city's population.[21] The arrival of Pashtuns and Punjabis from northern Pakistan further diversified the city's ethnic composition over the next few decades,[20] and by 1998, the percentage of Urdu speakers had fallen to 58%. Most Punjabis and Pakhtuns are distinct and separately living near the railway station and its vicinity. The city therefore has cosmopolitan atmosphere with multiethnic and multicultural communities. The city is now a multi-ethnic and has a mix of Sindhi, Urdu speaking Muhajirs, Brahuis, Punjabis, Pashtuns, Memons and Baloch people.

Religion

Hyderabad is noteworthy in Sindh and Pakistan generally for its comparative tolerance towards religious and ethnic minorities. The spread of Islamist militancy and extremism has been stymied in large parts of Sindh by vibrant civil society, and Sindh's progressive politics.[35]

The city has a long association with Sufism. In the 18th Century Syeds from Multan migrated and settled in the city's Tando Jahania neighbourhood, making it a sacred place for Muslims. The Syeds came from Uch Sharif, via Jahanian, 42 km from Multan). They were mostly descendants of Jahaniyan Jahangasht - a Sufi saint who is popular in Sindh and southern Punjab.[36][37][38][39] Hyderabad is near some of Sindh's most important Sufi shrines, being situated 49 kilometres (30 mi) from the joint Muslim-Hindu Shrine at Odero Lal, 59.3 kilometres (36.8 mi) from the Shrine of Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai, 146 kilometres (91 mi) from the Shrine of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar.[40]

Hindus once formed the majority in Hyderabad prior to 1948, and today account for the largest religious minority in Hyderabad - forming 5% of the total population of the city. Hyderabad's Amil Hindus clan of the Lohana caste had been employed previously the Talpur Mirs for their Persian language proficiency and skills in bureaucracy - this role continued under the British as the Amils were recruited into colonial administration.[9] The Amils formed the Amil Colony, which was where some of Hyderabad's finest colonial architecture was found.[9] The Bhaiband clan, also of the Lohana caste, dominated commerce in the city.[41]

While Christians account for 1% of the total population, Hyderabad is the seat of a Diocese of the Church of Pakistan and has five churches and a cathedral.

Geography

Location

Located at 25.367 °N latitude and 68.367 °E longitude with an elevation of 13 metres (43 ft), Hyderabad is located on the east bank of the Indus River and is roughly 150 kilometres (93 mi) away from Karachi, the provincial capital. Two of Pakistan's largest highways, the Indus Highway and the National Highway join at Hyderabad. Several towns surrounding the city include Kotri at 6.7 kilometres (4.2 mi), Jamshoro at 8.1 kilometres (5.0 mi), Hattri at 5.0 kilometres (3.1 mi) and Husri at 7.5 kilometres (4.7 mi).

Climate

Hyderabad has a hot desert climate (Köppen BWh), with warm conditions year-round. The city is famous for its winds which moderate the otherwise hot climate.[42] As a result, Hyderabadi homes traditionally feature "wind-catching" towers that funnel breezes down into living quarters in order to alleviate heat.[9]

The period from mid-April to late June (before the onset of the monsoon) is the hottest of the year, with highs peaking in May at 41.4 °C (106.5 °F). During this time, winds that blow usually bring along clouds of dust, and people prefer staying indoors in the daytime, while the breeze that flows at night is more pleasant. Winters are warm, with highs around 25 °C (77 °F), though lows can often drop below 10 °C (50 °F) at night. The highest temperature of 50 °C (122 °F) was recorded on 25 May 2018, while the lowest temperature of 1 °C (34 °F) was recorded on 8 February 2012.

In recent years, Hyderabad has seen great downpours. In February 2003, Hyderabad received 105 millimetres (4.13 in) of rain in 12 hours, leaving many dead.[43][44] The years of 2006 and 2007 saw close contenders to this record rain with death tolls estimated in the hundreds. The highest single-day rain total of 250.7 millimetres (9.87 in) was recorded on 12 September 1962, while the wettest month was September 1962, at 286 millimetres (11.26 in).

| Climate data for Hyderabad, Pakistan | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 33.3 (91.9) |

38.2 (100.8) |

43.4 (110.1) |

46.0 (114.8) |

48.4 (119.1) |

48.5 (119.3) |

45.5 (113.9) |

43.9 (111.0) |

45.0 (113.0) |

44.0 (111.2) |

41.0 (105.8) |

36.0 (96.8) |

48.5 (119.3) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 25.0 (77.0) |

28.1 (82.6) |

33.9 (93.0) |

38.9 (102.0) |

41.6 (106.9) |

40.2 (104.4) |

37.4 (99.3) |

36.3 (97.3) |

36.8 (98.2) |

37.2 (99.0) |

31.9 (89.4) |

26.3 (79.3) |

34.5 (94.0) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 11.1 (52.0) |

13.6 (56.5) |

18.5 (65.3) |

23.0 (73.4) |

26.2 (79.2) |

28.1 (82.6) |

27.8 (82.0) |

26.7 (80.1) |

25.3 (77.5) |

22.3 (72.1) |

17.3 (63.1) |

12.5 (54.5) |

21.0 (69.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 3.3 (37.9) |

4.0 (39.2) |

9.0 (48.2) |

12.0 (53.6) |

19.0 (66.2) |

20.0 (68.0) |

21.4 (70.5) |

22.8 (73.0) |

20.6 (69.1) |

15.0 (59.0) |

6.0 (42.8) |

3.0 (37.4) |

3.0 (37.4) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 1.2 (0.05) |

3.9 (0.15) |

5.1 (0.20) |

5.8 (0.23) |

3.5 (0.14) |

13.9 (0.55) |

56.7 (2.23) |

60.8 (2.39) |

21.4 (0.84) |

1.5 (0.06) |

2.1 (0.08) |

2.0 (0.08) |

177.9 (7) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 272.8 | 257.1 | 288.3 | 288.0 | 313.1 | 279.0 | 235.6 | 251.1 | 285.0 | 306.9 | 279.0 | 272.8 | 3,328.7 |

| Source 1: [45] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: HKO (sun only, 1969–1989) [46] | |||||||||||||

Topography

The city was initially founded on a limestone ridge on the eastern bank of the Indus River known as Ganjo Takkar, or "Bald Hill." The limestone outcropping provided several scenic vistas in the city, as well as inclined routes.[9] The most famous incline, the Tilak Incline, is named after the early 20th century independence activist Lokmanya Tilak.[9]

Economy

The industrial sector contributes 25% to the GDP of Pakistan, with a major concentration of industry in an arc stretching from Karachi to Hyderabad.[47] 75% of Sindh's industry is located in the Karachi-Hyderabad region.[48] The Sindh Industrial Trading Estate, home to 439 industrial units, was established on the outskirts of Hyderabad in 1950 which prospered with until the urban violence of the 1980s. Much of the city's industrial base was weakened by ethnic violence in urban Sindh in the 1980s, although poor infrastructure and supply of electricity has also hampered growth.[49]

Hyderabad is an important commercial center where industries includes: textiles, sugar, cement, manufacturing of mirror, soap, ice, paper, pottery, plastics, tanneries, hosiery mills and film. There are hide tanneries and sawmills. Handicraft industries, including silver and gold work, lacquer ware, ornamented silks, and embroidered leather saddles, are also well established.

Hyderabad produces almost all of the ornamental glass bangles in Pakistan, as well as layered glass inlay for jewelry.[50] The glass industry employs an estimated 300,000-350,000 people in manufacturing units centered on the Churi Parah neighbourhood.[49][51] The industry frequently uses recycled glass as material for its bangles.[51]

Hyderabad is surrounded by fertile alluvial plains, and is a major commercial center for the agricultural produce of the surrounding area, including millet, rice, wheat, cotton, and fruit.[52]

Cityscape

Local architecture

Hyderabad's local architectural patterns reflect the region's harsh climate and local customs. Walls of most traditional-style buildings were made of mud bricks, which helped keep the structure cool in summer and warm in winter.[23] Hyderabad is famed for its heat-relieving winds,[42] and so homes also featured wind-catchers that directed cool breezes into each homes' living quarters.[9]

Residential structures in Hyderabad's Old City, and in Hirabad typically have a small inward facing courtyard that afforded privacy from the city's streets. Walls facing the street are typically plain, though the home may display an elaborate entryway.[23] Inner courtyards and doorways of more elaborate homes would be decorated with jharoka balconies, floral motifs, ornamented ceilings, and decorative arches.[42] Most residential homes, however, were utilitarian in design.[42]

Homes built during the British colonial period contain introduced architectural elements like balconies and decorative columns as part of an elaborate outward-facing façade.[23] Such examples can be found in the Saddar neighborhood of Hyderabad. Large decorated windows were featured as part of Hyderabad's colonial style in order to ventilate the building.[42] Tall and multi-sectional windows with stained glass windows became a hallmark of Hyderabad's colonial-era architecture.[42] Homes of wealthy residents, especially among the city's Bhaiband community, the presence of windows was a marker of status, and allowed wealthy Hindus to practice the custom of purdah.[42] Balconies were sometimes affixed to the front of a building, and were typically made of wood or cast-iron.[42] Such homes would also sometimes have painted facades.[42]

Civic administration

Before the government of Abubaker Nizamani, the District Hyderabad included the present-day District of Badin. The longest-serving mayor of Hyderabad was Jamil Ahmed, who served from 1962 to 1971.

In 2005/2006, General Pervaiz Musharraf again divided it into four more districts Matiyari, Tando Allahyar, Tando Mohammad Khan and Hyderabad. Hyderabad district was subdivided into four talukas[53]

Judiciary

Court of District & Sessions Judge Hyderabad was established in 1899 under the subordination of Judicial Commissioner of Sindh.

Transportation

Road

The M-9 motorway is a 6 lane motorway that connects Hyderabad to Karachi, 136 kilometers away. The city will also be connected to Sukkur by the M-6 motorway, being built as part of the wider China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. From Sukkur, motorways will continue onward to Multan, Lahore, Islamabad, Faisalabad, and Peshawar.

Rail

Hyderabad Junction railway station serves as the city's main rail station. Passenger services are provided exclusively by Pakistan Railways. The city's station is serviced by the Allama Iqbal Express to Sialkot, the Badin Express, and the Khyber Mail to Peshawar. Hyderabad has trains to Nawabshah, Badin, Tando Adam Junction, Karachi, and points in northern Pakistan.

Air

Hyderabad Airport is no longer served by commercial air traffic. The last services were suspended in 2013. Passengers must now instead rely entirely on Karachi's Jinnah International Airport.

Education

75% of males and 65% of females over the age of 10 were literate in Hyderabad District in 2010,[54] a region which includes rural areas around the city. In 2010-2011, 2.96 Billion Rupees were spent on public education in Hyderabad District,[54] and number which increased to 3.99 Billion Rupees in 2011-2012.[54] 26% of children in Hyderabad District were enrolled in paid private schools in 2010.[54]

The University of Sindh was founded in Karachi in 1947, before moving to Hyderabad in 1951. The Liaquat University of Medical and Health Sciences was founded in nearby Jamshoro in 1951.

Sports

The Niaz Stadium of Hyderabad, with a seating capacity of 15,000 is home to the Hyderabad cricket team. It is known for Pakistani bowler Jalal-ud-Din's hat-trick, which was the first ever hat-trick taken by a bowler in a one-day match in 1982.[55] Hyderabad also has a hockey stadium.

Landmarks

- Pacco Qillo

- Tombs of Talpur Mirs

- Rani Bagh

- Sindh Museum

Media

Literature

As tradition goes, Sindh had always been a hub for Sufi poets. With a foothold on strong educational foundations, the city of Hyderabad was made into a refuge for thriving literary advocates. Of the few, Mirza Kalich Beg received education from the Government High School, Hyderabad and carried the banner of Sindhi literature across borders.[56] Modern novelists, writers, columnists and researchers like Musharraf Ali Farooqi, Ghulam Mustafa Khan and Qabil Ajmeri also hail from Hyderabad.

Hyderabad has served many Sindhi literary campaigns throughout the history of Pakistan as is evident from the daily newspapers and periodicals that are published in the city. A few worth mention dailies are the Kawish,[57] Ibrat,[58] and Daily Sindh.[59]

Radio and television

With the inauguration of a new broadcasting house at Karachi in 1950, it was possible to lay the foundations for the Hyderabad radio station in 1951. The initial broadcast was made capable using 1 kW medium-wave transmitter. With the first successful transmissions on the FM 100 bandwidth in Karachi, Lahore and Islamabad in October 1998, the Government decided on opening transmissions to other cities where Radio Pakistan had found success. This made available the FM 101 bandwidth transmissions to Hyderabad and other cities in Sindh.[60]

A relief from the regular broadcasts in other cities, entertainment content on the Hyderabad radio gave birth to many a star whose names became an attribute to Hyderabad's richer media content. Among them were actor Shafi Mohammad, a young man who had recently finished his postgraduate degree from the University of Sindh.[61] Such fresh and young talent became a trademark to entertainment in Hyderabad.

Pakistan Television had only had half-a-decade broadcast success from 1963 to 1969 that people in the radio entertainment business felt destined to make a mark on the television circuits. Prominent radio personalities from the Hyderabad radio station like Shafi Muhammad Shah and Mohammad Ali left the airwaves to hone their acting skills on the television.[62] Television shows and content enriched with the inclusion of Hyderabadi names however PTV never opened a television station in Hyderabad.

While the year 2005 saw new FM regular stations set up at Gawadar, Mianwali, Sargodha, Kohat, Bannu and Mithi, private radio channels began airing in and around Hyderabad. Of late, stations like Sachal FM 105 and some others have gained popularity. But the unavailability of an up-to-date news and current affairs platform renders the services of such stations of not much value to the masses but nonetheless appealing to youngsters.

As the Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority (abbreviated as PEMRA) gave licenses to private radio channels, so were television channels owned privately given a right to broadcast from the year 2002,[63] and Daily Kawish,[57] a prominent Sindhi newspaper published from Hyderabad opened a one-of-its-kind private Sindhi channel Kawish Television Network. Many followed in its path namely Sindh TV, Dhoom TV and Kashish TV premiering Sindhi content.

Notable people

- Hoshu Sheedi, General of Talpur Mirs' Army, which fought against British in the Battles of Miani and last Battle of Dubbo.

- Jivatram Kripalani (1886–1982), Indian politician and Indian independence activist.

- Mirza Kalich Beg (1853–1929), civil servant and author

- K. R. Malkani (1921–2003), Indian politician. Lieutenant-Governor of Pondicherry (2002–03)

- Allama Imdad Ali Imam Ali Kazi (1886–1968), philosopher and scholar

- Sadhu T. L. Vaswani (1879–1966), Hindu spiritualist. Founder of the Sadhu Vaswani Mission.

- Nabi Bakhsh Khan Baloch (1917–2011), linguist and author

- Muhammad Ibrahim Joyo (born 1915), scholar and translator

- Rizwan Ahmed, Secretary to Government of Pakistan

- Ghulam Mustafa Khan (born 1912), researcher, and linguist

- Choudry Mohammad Sadiq (1900–1975), politician and Muslim Leaguer

- Syed Qamar Zaman Shah (born 1933), the nephew and son-in-law of Late Syed Miran Mohammad Shah. Senator during the early 1970s.

- Syed Miran Mohammad Shah, former speaker of Sindh legislative Assembly, Minister in the Sindh Government, former Ambassador of Pakistan to Spain.

- Qabil Ajmeri (1931–1962), recognised as a "senior" poet of Urdu

See also

Notes

- https://www.citypopulation.de/php/pakistan-distr-admin.php

- "Pakistan: Provinces and Major Cities - Population Statistics, Maps, Charts, Weather and Web Information". www.citypopulation.de.

- "DISTRICT WISE CENSUS RESULTS CENSUS 2017" (PDF). www.pbscensus.gov.pk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 August 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- https://www.undp.org/content/dam/pakistan/docs/HDR/HDI%20Report_2017.pdf

- "By winning 2nd largest city Hyderabad and 4th largest city Mirpurkhas, MQM declared Urban Sindh Lead | Siasat.pk Forums". Siasat.pk. 19 November 2015. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- "Hyderabad". Population Welfare Department - Government of Sindh. Archived from the original on 14 December 2017. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- Everett-Heath, John (2005). Concise dictionary of world place names. Oxford University Press. p. 223. ISBN 978-0-19-860537-9.

- Mir Atta Muhammad Talpur. "The Vanishing Glory of Hyderabad (Sindh, Pakistan)" (PDF). UNIOR Web Journals]. Retrieved 1 April 2008.

- Talpur, Mir Atta Muhammad (2007). "The Vanishing Glory of Hyderabad (Sindh, Pakistan)" (PDF). Web Journal on Cultural Patrimony. University of Naples. ISSN 1827-8868.

- "Pakka Qila Hyderabad". abbasikalhora.com. Archived from the original on 4 July 2014. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- "Hyderabad". Humshehri. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- A Comprehensive History of India, Volume 3. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. 2003. ISBN 8120725069. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- "Hyderābād City – Imperial Gazetteer of India v. 13, p. 321". Imperial Gazetteer of India. Retrieved 3 April 2008.

- Antunes, Cátia (2016). Explorations in History and Globalization. Routledge. ISBN 978-1317243847. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- Stanziani, A (2012). Labour, Coercion, and Economic Growth in Eurasia, 17th-20th Centuries. Brill. ISBN 9789004236455. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- "Navalrai Clock Tower". Heritage of Sindh. The Endowment Fund Trust for the Preservation of Heritage of Sindh. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- Malkani, K. R. (1984). The Sindh Story. Sindhi Academy, Delhi. ISBN 8187096012.

- Kumar, Priya (2 December 2016). "Sindh, 1947 and Beyond". South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies. Routledge. 39 (4): 773–789. doi:10.1080/00856401.2016.1244752.

- Chitkara, M. G. (1996). Mohajir's Pakistan. APH Publishing. ISBN 8170247462. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- Donnan, Hastings (1991). Economy and Culture in Pakistan: Migrants and Cities in a Muslim Society. Springer. ISBN 1349114014. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- Jones, Owen Bennett (2003). Pakistan: Eye of the Storm. Yale. p. 113. ISBN 0300101473. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

hyderabad heart of sindh.

- Verkaaik, Oskar (2004). Migrants and Militants: Fun and Urban Violence in Pakistan. Princeton University Press. p. 98. ISBN 0691117098. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

hyderabad.

- Ekram, Lailun (1995). "Khuda Ki Basti Incremental Development Scheme" (PDF). 1995 Technical Review. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- "Pakistan Backgrounder". South Asia Terrorism Portal. Retrieved 14 April 2008.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 12 September 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Ethnic Rioting in Karachi Kills 46 and Injures 50 - The New York Times". Nytimes.com. Reuters. 2 October 1988. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- Col. Ved Prakash (2011). Encyclopaedia of Terrorism in the World, Volume 1. Kalpaz publication. ISBN 978-81-7835-869-7. Retrieved 12 September 2015.

- Siddiqi, Farhan Hanif (2012). The Politics of Ethnicity in Pakistan: The Baloch, Sindhi and Mohajir Ethnic Movements. Routledge. ISBN 978-1136336966. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- Rubin, Judith Colp (2008). Chronologies of Modern Terrorism. ME Sharpe. p. 280. ISBN 978-0765622068. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

hyderabad pakistan.

- Elahi, Asad (2006). "2: Population" (PDF). Pakistan Statistical Pocket Book 2006. Islamabad, Pakistan: Government of Pakistan: Statistics Division. p. 28. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- DISTRICT WISE CENSUS RESULTS CENSUS 2017 (PDF) (Report). Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. 2017. p. 13. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 August 2017. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- "PROVISIONAL SUMMARY RESULTS OF 6TH POPULATION AND HOUSING CENSUS-2017". pbs.gov.pk. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- "Pakistan's top 10 most populated cities as per Census 2017". Times of Islamabad. 26 August 2017. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- Gopinath, Pillai (2016). 50 Years Of Indian Community In Singapore. World Scientific. ISBN 978-9813140608. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- Hasan, Syed Shoaib; Yusuf, Huma (January 2015). "CONFLICT DYNAMICS IN SINDH" (PDF). Peaceworks. United States Institute of Peace. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- Uch Sharif (18 December 2011). "Safarnama Makhdoom Jahanian Jahangasht". Uchsharif.com. Archived from the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- "UCH Sharif Trust | Understanding of Culture and Heritage | An Ancient Tradition". Archived from the original on 18 May 2016. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- "Sufis & Shaykhs [4] – World of Tasawwuf". Spiritualfoundation.net. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- "Tomb of Bibi Jawindi, Baha'al-Halim and Ustead and the Tomb and Mosque of Jalaluddin Bukhari – UNESCO World Heritage Centre". Whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- Google Maps

- Markovits, C (2008). Merchants, Traders, Entrepreneurs: Indian Business in the Colonial Era. Springer. ISBN 9780230594869. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- Jatt, Zahida Rehman (2016). "Download citationShare Download full-text PDF Ad AESTHETICS AND ORGANIZATION OF SPACES: A CASE STUDY OF COLONIAL ERA BUILDINGS IN HYDERABAD, SINDH". Journal of Research in Architecture and Planning. 20 (1). Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- "Pakistan floods leave many dead". BBC News. 18 February 2003.

- "World Briefing – Asia: Pakistan: Floods Kill 88 And Maroon 100,000 \". The New York Times. 30 July 2003.

- "World Weather Information Service". Worldweather.wmo.int. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- "Climatological Information for Hyderabad, Pakistan". Hong Kong Observatory. Retrieved 4 May 2011.

- Sharp, Rhonda (2010). "Islamic Republic of Pakistan" (PDF). University of South Australia. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- Memon, Naseer (9 July 2017). "Tackling unemployment in rural Sindh". The News (Pakistan). Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- Parmar, Vishnu (July 2005). "Investment Trends in Hyderabad, Pakistan". Journal of Independent Studies and Research. SZABIST. 3 (2).

- Mills, Margaret Ann (2003). South Asian Folklore: An Encyclopedia : Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0415939194. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- Soomro, Marvi. "Cut from glass: The perilous lives of Hyderabad's bangle makers". Dawn. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- "Pakistan Backgrounder". South Asia Terrorism Portal. Retrieved 15 April 2008.

- Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- "Hyderabad" (PDF). ASER Pakistan. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- "1st ODI: Pakistan v Australia at Hyderabad (Sind), Sep 20, 1982". Cricinfo. Retrieved 11 July 2009.

- "Mirza Kalich Beg: Renowned scholar of Sindh". Retrieved 18 March 2008.

- "Read Daily Kawish online". Daily Kawish. Archived from the original on 2 June 2007. Retrieved 21 May 2008.

- "Read Daily Ibrat online". Daily Ibrat. Retrieved 21 May 2008.

- "Read Daily Sindh online". Daily Sindh. Retrieved 21 May 2008.

- "Radio Pakistan: Chronicle of Progress". Radio Pakistan. Archived from the original on 14 February 2008. Retrieved 18 March 2008.

- "Actor Shafi Muhammad passes away". Retrieved 18 March 2008.

- "Pakistan's Top Film Star Muhammad Ali Dies". Pakistan Tribune. Retrieved 18 March 2008.

- "PEMRA Ordinance 2002" (PDF). Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2007. Retrieved 18 March 2008.

References

- Biographical Encyclopedia of Pakistan 1963–1966 edition.

External links

- Official website of the City District Government of Hyderabad

- Hyderabad Local Directory Listing Website