Carlow

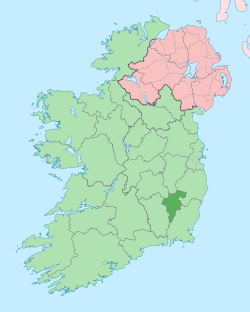

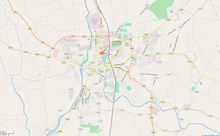

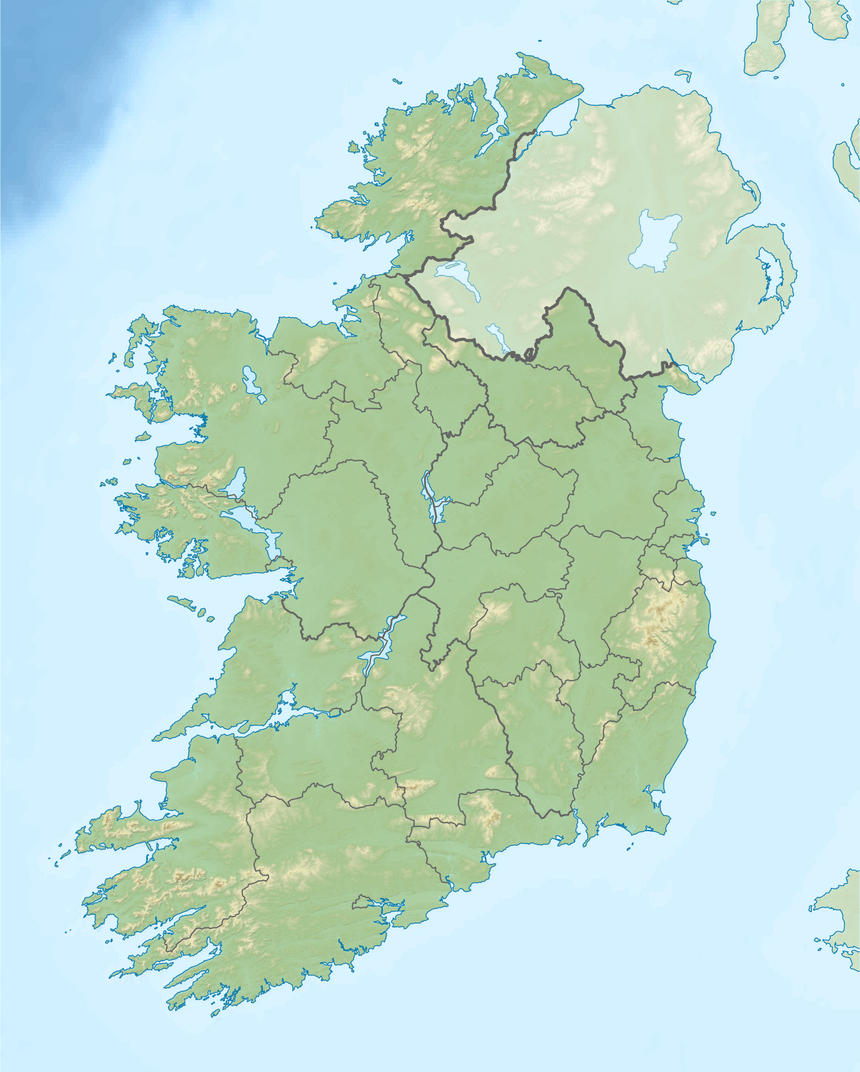

Carlow (/ˈkɑːr.loʊ/ KAR-loh; Irish: Ceatharlach) is the county town of County Carlow, in the south-east of Ireland, 84 km (52 mi) from Dublin. At the 2016 census, it had a combined urban and rural population of 24,272.[3]

Carlow Ceatharlach | |

|---|---|

Town | |

| |

Coat of arms | |

Carlow Location in Ireland  Carlow Carlow (Europe) | |

| Coordinates: 52.8306°N 6.9317°W | |

| Country | Ireland |

| Province | Leinster |

| County | County Carlow |

| Dáil Éireann | Carlow–Kilkenny |

| Government | |

| • Type | Carlow Municipal District |

| • Mayor | Andrea Dalton |

| Area | |

| • Total | 11.8 km2 (4.6 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 57 m (187 ft) |

| Population (2016)[3] | |

| • Total | 24,272 |

| • Rank | 13th |

| • Density | 2,100/km2 (5,300/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC±0 (WET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (IST) |

| Eircode routing key | R93 |

| Telephone area code | +353(0)59 |

| Irish Grid Reference | S724771 |

| Website | www |

The River Barrow flows through the town, and forms the historic boundary between counties Laois and Carlow. However, the Local Government (Ireland) Act 1898 included the town entirely in County Carlow. The settlement of Carlow is thousands of years old and pre-dates written Irish history. The town has played a major role in Irish history, serving as the capital of the country in the 14th century.

Etymology

The name is an anglicisation of the Irish Ceatharlach. Historically, it was anglicised as Caherlagh,[4] Caterlagh[5] and Catherlagh,[6] which are closer to the Irish spelling. According to logainm.ie, the first part of the name derives from the Old Irish word cethrae ("animals, cattle, herds, flocks"),[7] which is related to ceathar ("four") and therefore signified "four-legged".[8] The second part of the name is the ending -lach.

Some believe that the name should be Ceatharloch (meaning "quadruple lake"),[9] since ceathar means "four" and loch means "lake". It is directly translated as "Four lakes", although, there is seemingly no evidence to suggest that these lakes ever existed in this area.

History

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1813 | 6,146 | — |

| 1821 | 8,035 | +30.7% |

| 1831 | 9,114 | +13.4% |

| 1841 | 10,409 | +14.2% |

| 1851 | 8,690 | −16.5% |

| 1861 | 8,344 | −4.0% |

| 1871 | 7,842 | −6.0% |

| 1881 | 7,185 | −8.4% |

| 1891 | 6,619 | −7.9% |

| 1901 | 6,513 | −1.6% |

| 1911 | 6,619 | +1.6% |

| 1926 | 7,163 | +8.2% |

| 1936 | 7,649 | +6.8% |

| 1946 | 7,466 | −2.4% |

| 1951 | 7,667 | +2.7% |

| 1956 | 8,445 | +10.1% |

| 1961 | 8,920 | +5.6% |

| 1966 | 9,765 | +9.5% |

| 1971 | 10,399 | +6.5% |

| 1981 | 13,164 | +26.6% |

| 1986 | 13,816 | +5.0% |

| 1991 | 14,027 | +1.5% |

| 1996 | 14,979 | +6.8% |

| 2002 | 18,487 | +23.4% |

| 2006 | 20,724 | +12.1% |

| 2011 | 23,030 | +11.1% |

| 2016 | 24,272 | +5.4% |

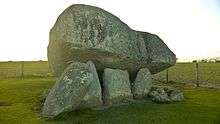

Evidence shows that human occupation in the Carlow county area extends back thousands of years. The most notable and dramatic prehistoric site is the Browneshill Dolmen – a megalithic portal tomb just outside Carlow town.

Now part of the diocese of Kildare and Leighlin, several Early Christian settlements are still in evidence today around the county. St Mullin's monastery is believed to have been established around the 7th century, the ruins of which are still in evidence today. Old Leighlin was the site of one of the largest monastic settlements in Ireland and the location for a church synod in 630 AD which determined the date of Easter. St Comhgall built a monastery in the Carlow area in the 6th century, an old church building and burial ground survive today at Castle Hill known as Mary's Abbey. Carlow was an Irish stronghold for agriculture in the early 1800s which earned the county the nickname of the scallion eaters. Famine later wiped out half of the population.

Carlow Castle was constructed by William Marshal, Earl of Striguil and Lord of Leinster, c1207-13, to guard the vital river crossing. It was also to serve as the capital of the Lordship of Ireland from 1361 until 1374. This imposing structure survived largely intact until 1814 when it was mostly destroyed in an attempt to turn the building into a lunatic asylum. The present remains now are the West Wall with two of its cylindrical towers. The bridge over the river Barrow – Graiguecullen Bridge, is agreed to date to 1569. The original structure was largely replaced and widened in 1815 when it was named Wellington Bridge in celebration of the defeat of Napoleon's army by the Duke of Wellington at the Battle of Waterloo in June of that year. The bridge was built across a small island in the river and a 19th-century house was constructed on the bridge – this was for a time occupied by the Poor Clares, an enclosed religious order who still have a convent in Graiguecullen. Another convent belonging to the Presentation Order of nuns now houses the County Library and the Carlow County Museum. The Cathedral, designed by Thomas Cobden, was the first Catholic cathedral to be built in Ireland after Catholic Emancipation in 1829. Its construction cost £9,000 and was completed in 1833. Beside the cathedral, Saint Patrick's College dates from 1793. The College was established in 1782 to teach the humanities to both lay students and those studying for the priesthood. The Carlow Courthouse was constructed in the 19th century. There are still many old estates and houses in the surrounding areas, among them Ducketts Grove and Dunleckney Manor.[10] St Mullin's today houses a heritage centre.

In 1703 the Irish House of Commons appointed a committee to bring in a bill to make the Barrow navigable; by 1800 the Barrow Track was completed between St. Mullin's and Athy, establishing a link to the Grand Canal which runs between Dublin and the Shannon. By 1845 88,000 tons of goods were being transported on the Barrow Navigation. Carlow was also one of the earliest towns to be connected by train. The Great Southern and Western Railway had opened its main line as far as Carlow in 1846, and this was extended further to Cork in 1849. The chief engineer, William Dargan, originally hailed from Killeshin, just outside Carlow. At the peak of rail transport in Ireland, Carlow county was also served by a line to Tullow. Public supply of electricity in Carlow was first provided from Milford Mills, approximately 8 km south of Carlow, in 1891. Milford Mills still generates electricity feeding into the national grid. Following independence in the early 1920s the new government of the Irish Free State decided to establish a sugar-processing plant in Leinster. Carlow was chosen as the location due to its transport links and large agricultural hinterland, favourable for growing sugar beet.

The town is recalled in the famous Irish folk song, Follow Me Up to Carlow, written in the 19th century about the Battle of Glenmalure, part of the Desmond Rebellions of the late 16th century. In 1650, during the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland, Carlow was besieged and taken by English Parliamentarian forces, hastening the end of the Siege of Waterford and the capitulation of that city. During the 1798 rebellion Carlow was the scene of a massacre of 600 rebels and civilians following an unsuccessful attack on the town by the United Irishmen, known as the Battle of Carlow. The Liberty Tree sculpture in Carlow, designed by John Behan, commemorates the events of 1798. The rebels slain in Carlow town are buried in the 'Croppies Grave', in '98 Street, Graiguecullen.[11]

Irish language

Down to the early 19th century Irish was spoken in all twelve counties of the province of Leinster, of which County Carlow is part. According to Celtic scholar Nicholas Williams, the Irish spoken in County Carlow seems to have belonged to a central dialect stretching from west Connacht eastwards to the Liffey estuary. It had characteristics which survive today only in the Irish of Connacht. It preserved the stress pattern of Old Irish in which the first syllable of a word receives strong stress. Evidence from place-names suggest that Old Irish cn- had become "cr-" in parts of Carlow, like all Gaelic speech outside of Munster and Ossory. An example from Carlow is Crukeen (Cnoicín).[12]. West Carlow seems to have pronounced "slender R" as "slender Z" (like the "s" in "treasure" or "pleasure") which is also a well-attested feature of the (now extinct) traditional dialects of Kilkenny and South Laois.

Efforts are now being made to increase the use of Irish in Carlow under the aegis of the organisation Glór Cheatharlach. Carlow has two schools which teach through Irish: a Gaelscoil (primary) and a Gaelcholáiste (secondary), both at full capacity and supplemented by an Irish-speaking pre-school or Naíonra. There is also an intensive Irish-language summer course for students from English-speaking schools. It has been claimed that there is more Irish spoken in Carlow than in certain Gaeltacht districts.[13][14]

Media

The Nationalist is a newspaper which was established in 1883.[15] The Carlow People is a free weekly newspaper[16]

Places of interest

One of Carlow's most notable landmarks is the Brownshill Dolmen, situated on the Hacketstown Road (R726) approximately 5 km from Carlow town centre. The capstone of this dolmen is reputed to be the largest in Europe.

Carlow Castle was probably built between 1207 and 1213 by William Marshall on the site of a motte erected by Hugh de Lacy in the 1180s. Only the western wall and two towers now survive. It is located on the banks of the River Barrow near Carlow town centre.[17] The castle is now the centrepiece of an urban renewal programme.[18]

Carlow Courthouse is situated at the end of Dublin Street. It was designed by William Vitruvius Morrison in 1830 and completed in 1834. It is built of Carlow granite and gives the impression of being a temple set on a high plinth. The basement contains cells and dungeons. A cannon from the Crimean War stands on the steps.[19]

Carlow Town Hall is situated on the north side of the Haymarket, and was the trading centre for Carlow. A number of other markets were located around the town, including the Potato Market and Butter Market. The Town Hall was designed by the church architect William Hague in 1884.[20]

Milford is a green area on the River Barrow approx 5 miles outside of Carlow town. It is notable as its home to Milford Mill, which was the first inland hydro-electrical plant in Ireland. It began supplying Carlow town with power in 1891.[21]

The estate at Oak Park is located 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) north of Carlow.

Economy

Carlow industry has come a long way since the early 20th century, when the town became the centre of Ireland's slow process of industrialisation with the creation of the Irish Sugar Company. Then at the cutting edge of industry in Ireland, the sugar factory opened in 1926 as a private enterprise and was eventually nationalised before reverting to private ownership. It closed on 11 March 2005 as the management of the parent company Greencore decided that it was no longer economical to run the factory nor was it viable to upgrade the facility. The country's last remaining sugar plant at Mallow, County Cork closed in 2006.

One of the traditional, principal employers in Carlow was OralB Braun, which had a large factory producing mostly hair dryers and electric toothbrushes; however this closed in 2010. Burnside is also a large employer in the area; it produces hydraulic cylinders. The Institute of Technology is also a significant employer in the town. Since opening its doors in October 2003 Fairgreen Shopping Centre has also played a large part in employment in the area; Tesco, Heatons, Next, New Look and River Island are the main tenants. Nonetheless, the town shares problems associated with other provincial towns in Ireland – the inability to attract significant new industry. Pharmaceutical giant Merck & Co. intends to build a new vaccine manufacturing plant in Carlow.[22]

Transport

The N9 road from Dublin to Waterford passed directly through the town until May 2008 when a bypass, part of the M9 motorway, was opened, greatly reducing traffic through the town. The N80 National secondary road skirts the edge of the town. The town is also connected to the national rail network. These transport links have helped Carlow to become a successful satellite town of Dublin in recent years. The establishment of the Institute of Technology, Carlow, has also helped drive growth in the area and encouraged many school leavers to remain in the town. Carlow railway station opened on 4 August 1846 and was closed for goods traffic on 9 June 1976[23], it remains open for public travel.

Education

Secondary schools serving the area include Gaelcholáiste Cheatharlach, Presentation College, Tyndall College (including the former Carlow Vocational School), Tullow Community School, St Leo's College, and St Mary's Knockbeg College.[24]

Third-level institutions include the Institute of Technology, Carlow, Carlow Institute of Further Education, and St. Patrick's, Carlow College. The latter, opened in 1793, was the first post-penal Catholic seminary constructed in Ireland. It is built in the form of a large country house and claims to be the seminary in longest continuous use worldwide.[25][26]

Religion

Carlow Cathedral dedicated to Our Lady of Assumption, was started in 1828 and completed in 1833, in Gothic style. The main architect was Thomas Cobden, but the cathedral was the brain-child of the Bishop of Kildare and Leighlin, James Doyle (J.K.L.), a prominent champion of Catholic Emancipation, who died the year after the cathedral was opened and is interred in its walls. A sculpture by John Hogan is a memorial to the bishop and was finished in 1839.[27] An unidentified baby was left here on 22 January 2010.[28][29]

St. Mary's Church of Ireland dates from 1727, though the tower and spire, built to a height of 59 m (195 ft) were added in 1834. The interior retains its traditional galleries and there are several monuments, including some by neo-classical architect, Sir Richard Morrison.[30]

Sport

Motor racing

On 2 July 1903, the Gordon Bennett Cup ran through Carlow. It was the first international motor race to be held in Great Britain or Ireland. The Automobile Club of Great Britain and Ireland wanted the race to be hosted in the British Isles, Ireland was suggested as the venue because racing was illegal on British public roads. After some lobbying and changes to local laws, Kildare was chosen, partly because the straightness of its roads would be a safety benefit. As a compliment to Ireland the British team chose to race in Shamrock green[Note 1] which thus became known as British racing green.[31][32][33][34] The route consisted of several laps of a circuit passed-through Kilcullen, Kildare, Monasterevin, Stradbally, Athy, Castledermot and Carlow. The 328 miles (528 km) race was won by the Belgian racer Camille Jenatzy, driving a Mercedes.[35][32]

Racquetball

The Carlow Racquetball club was set up in 1978. The club is one of only 7 in the south eastern region and is the largest of these.

Clubs

GAA clubs in the area include Tinryland GAA Club, Éire Óg GAA Club, Asca GAA Club, Palatine GAA club, and O'Hanrahans GAA Club.

County Carlow Football Club is the local rugby union club, while F.C. Carlow is a local association football (soccer) club.

Carlow also has boxing clubs, an athletics club (St Laurence O'Toole Athletics Club), golf club, rowing club, tennis club, hockey club and the Carlow Jaguar Scooter Club. (Founded in 1979, this latter club is one of the longest running scooter clubs in Ireland or England).

People

- John Tyndall (1820-1893) - physicist

- John Lyons (1824-1867) - recipient of the Victoria Cross

- Arthur MacMurrough Kavanagh (1831-1889) - politician

- John Augustine Sheppard (1849-1925) - Monsignor, Vicar general of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Newark

- Kathryn Thomas (b. 1979), television presenter for RTÉ

- Seán O'Brien (b. 1987) - Irish international rugby player

- John Gibbons - record producer, DJ

- Pádraig Amond (b. 1988) - Irish professional footballer who plays for Newport County

- Saoirse Ronan (b. 1994) - actress

Twin towns

Carlow is twinned with the following places:

See also

- List of towns and villages in Ireland

- High Sheriff of Carlow

- Lyster – English occupational surname, mentioned in histories as transplanted to Ireland in Carlow

Notes

- According to Leinster Leader, Saturday, 11 April 1903, Britain had to choose a different colour to its usual national colours of red, white and blue, as these had already been taken by Italy, Germany and France respectively. It also stated red as the color for American cars in the 1903 Gordon Bennett Cup.

References

- "Carlow Municipal District". Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- "Population Density and Area Size 2016". CSO. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- "Census 2016 Sapmap Area: Settlement Carlow. Theme 1: Sex, Age and Marital Status. Population aged 0-9 by sex and year of age, population aged 20+ by sex and age group". Central Statistics Office. Retrieved 22 October 2018.

- A census of Ireland, circa 1659: with essential materials from the poll money ordinances 1660–1661. Irish Manuscripts Commission, 2002. Page 11.

- Hyde, Edward. The History of the Rebellion and Civil Wars in England. Oxford University Press, 1839. Page 211.

- The civil survey, AD 1654–1656. Irish Manuscripts Commission, 1961. Page 9.

- eDIL Electronic Dictionary of the Irish Language Archived 24 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- "Ceatharlach". Retrieved 24 April 2011.

- Flanagan, Deirdre; Laurence Flanagan (1994). Irish Place Names. Dublin: Gill & Macmillan. p. 188. ISBN 0-7171-2066-X.

- "Dunleckney Manor, County Carlow". National Inventory of Architectural Heritage. Department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- "The Liberty Tree". Carlow Town.com. Archived from the original on 17 November 2007. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- Williams, Nicholas. “Na Canúintí a Theacht chun Solais” in Stair na Gaeilge, ed. Kim McCone et al.. Maigh Nuad 1994, pp. 467-478. ISBN 0-901519-90-1

- "Gaeil Cheatharlach ag iarraidh stádas a bhaint amach mar bhaile dátheangach". tuairisc.ie. Tuairisc.ie. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- "Bilingual town Carlow steps up efforts to become landmark Irish language destination". carlowlive.ie. Carlow Live. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- The website of The Nationalist

- "Carlow People".

- "Carlow Castle". Carlow Town.com. Archived from the original on 17 November 2007. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- "Carlow Castle, Carlow town". Carlow Tourism – Castles. Archived from the original on 11 March 2005. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- "Carlow Courthouse". Carlow Town.com. Archived from the original on 17 November 2007. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- "Carlow Town Hall". Carlow Town.com. Archived from the original on 17 November 2007. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- "Milford". Carlow County Museum. Archived from the original on 10 June 2015. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- Merck invests EUR200m in Carlow facility Archived 29 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine story dated 27 November 2007 on ENN website. Retrieved 16 October 2008

- "Carlow station" (PDF). Railscot – Irish Railways. Retrieved 30 August 2007.

- "Secondary Schools Listings , Carlow". schooldays.ie. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- "St Patrick's College". Carlow Town.com. Archived from the original on 17 November 2007. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- J. Garaty, The Carlow Connection: The contribution of Irish seminarians in 19th century Australia, Journal of the Australian Catholic Historical Society 35 (2014) Archived 15 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine, 10-21.

- "Carlow Cathedral". Carlow Town.com. Archived from the original on 17 November 2007. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- RTÉ. "Baby left in Carlow Cathedral". Friday, 22 January 2010 22:10

- The Irish Times – Last Updated: Friday, 22 January 2010, 21:58. "Baby abandoned in Carlow Cathedral". PAMELA NEWENHAM.

- "St Mary's Church". Carlow Town.com. Archived from the original on 17 November 2007. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- Circle Genealogic and Historic Champanellois Archived 5 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- "Leinster Leader April 1903 - Review of the coming Gordon Bennett Race". Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- Forix 8W – Britain's first international motor race by Brendan Lynch, based on his Triumph of the Red Devil, the 1903 Irish Gordon Bennett Cup Race. 22 October 2003

- "8W - When? - The Gordon Bennett races". Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- Duncan Scott. "The Birth Of British Motor Racing". Bleacher Report. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carlow. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Carlow. |