Ice road

An ice road (ice crossing, ice bridge) is a winter road, or part thereof, that runs on a naturally frozen water surface (a river, a lake or an expanse of sea ice) in cold regions. Ice roads allow temporary transport to isolated areas with no permanent road access. They reduce transportation cost of materials that otherwise would ship as expensive air freight, and they allow movement of large or heavy objects for which air freight is impractical.

Ice roads may be winter substitutes for summer ferry services. Ferry service and an ice crossing may operate yearly at the same time for several weeks.

Function

Ice roads provide a flat, smooth driving surface devoid of trees, rocks, and other obstacles. They can be snow plowed, and may comprise a series of short overland portages - overland segments linking lakes. Similar to ice roads, ice runways are common in the polar regions and include the blue ice runways such as Wilkins Runway in Antarctica or lake ice runways like Doris Lake Aerodrome in the Arctic. Ice can also be used as an emergency landing surface.

In general, these roads are built in areas where construction of year-round roads is expensive due to boggy muskeg land and a number of other reasons. In the winter, these obstacles are therefore easier to cross. Ice roads, such as the stretch between Inuvik and Tuktoyaktuk, Northwest Territories, Canada, provide an almost level driving surface with few detours several months of the year.

When frozen in winter, the waterway crossings can be built up with auger holes to flood and thicken the crossing. The act of clearing snow quickly makes ice thicker by exposing the road directly to subfreezing air (temperatures as low as −50 °C (−58 °F)). In the summer, after the ice melts, effects of the roads can still be seen from overhead in a bush plane, as bare strips remain on the lake floor where the ice blocked light and prevented plants and algae from growing.

Often there is a car ferry used in summer time. There are normally periods in spring and fall where there is too much ice for the ferry, but too little for an ice road.

Driving

While easier to drive across in the winter than land, roads over water present a great danger to anyone using them. Speeds are typically limited to 25 km/h (16 mph) to prevent a truck's weight from causing waves under the surface. These waves can damage the road, or dislodge the ice from the shoreline and create a hazard. Another hazard on large lakes is the pressure ridge, a break in the ice created by the expansion and contraction of the surface ice due to variations in temperature.

The roads are normally the domain of large trucks (e.g. tractor-trailer units), although lighter vehicles, such as pickup trucks, even small cars, can be seen, as are snowmobiles.

Use of ice as the main construction material allows unusual construction techniques: to make a ramp to get the road over a step such as the shore of a lake, for example, lake water is pumped out and mixed with snow to make slush, formed into the shape of the ramp, and allowed to quickly freeze in the intense cold. Worn and damaged roads are repaired by flooding with shallow water that freezes into a new surface layer.[1]

Around the world

Antarctica

The South Pole Traverse (McMurdo-South Pole highway) is approximately 1,400 km (870 mi) long and links the United States' McMurdo Station on the coast to the Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station. It was constructed by leveling snow and filling in crevasses, but is not paved. There are flags to mark the route.

Also, the United States Antarctic Program maintains two ice roads during the austral summer. One provides access to Pegasus Field on the Ross Ice Shelf. The ice road between Pegasus Field and McMurdo Station is about 14 miles. The other road provides access to the Ice Runway, which is on sea ice. The road between the Ice Runway and McMurdo Station varies in length from year to year depending on many factors, including ice stability. These roads are critical for resupplying McMurdo Station, Scott Base, and Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station.

Canada

Some of the first ice roads in history were built in the 1930s in northern Canada, for use by caterpillar sleds pulling heavy loads called tractor trains for mines where loads were too heavy for transport by aircraft and the soil too boggy for standard roads when the land was not frozen.[2] Tractor-freighting was eventually phased out in the north and replaced with truck transport over well-maintained ice roads; in the far north, these were first engineered by Al Hamilton of Grimshaw Transport in the 1950s and later improved by John Denison of Byers Transport in the 1960s, and Robinson's Trucking in the 1980s.

Winter roads and ice roads in Canada are found primarily in northern parts of some provinces, as well as the sparsely-populated northern territories of Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut. In Nunavut, while there are a number of permanent roads within the territory, the Tibbitt to Contwoyto Winter Road, linking Nunavut to Tibbitt Lake in the Northwest Territories, forms the territory's only road access to the rest of North America's road network.

Winter roads in the Northwest Territories, most notably the Tuktoyaktuk Winter Road (which has since been replaced by an all-season highway), link various isolated communities and mineral exploration sites to the territory's highway network. One exception to the usual purpose of an ice road is the winter link between the territorial capital city of Yellowknife and the village of Detah, which crosses a branch of Great Slave Lake during the winter months; there is an all-year road linking Detah to Yellowknife, but the ice road allows for a much shorter link between the two centres during the winter.

Winter roads may also be found in the sparsely populated northernmost regions of some Canadian provinces. Most communities north of Ontario's Albany River are served by winter roads. Most of these roads in Northwestern Ontario are linked to the Northern Ontario Resource Trail, a permanent gravel road which extends northerly from the end of Highway 599 at Pickle Lake, the northernmost community in the province with year-round highway access. In Northeastern Ontario, some communities are linked to Moosonee, a town that has rail access but no road access to the south.

Saskatchewan also has an ice road in the southern part of the province at the Riverhurst Ferry.[3]

People's Republic of China

Transport links between Russia and China rely heavily on ice roads which link border Chinese and Russian towns/cities. Because winter temperatures in the Sino-Russian border have average January minima between −20 and −25 °C (−4 and −13 °F), border rivers such as the Amur and Ussuri are well frozen by late October/early November. Russian and Chinese border trade heavily rely on the ice roads. Notable examples include the ice road linking the Chinese city of Heihe and the Russian city of Blagoveshchensk, and the ice road linking Suifenhe in China and Pogranichny.

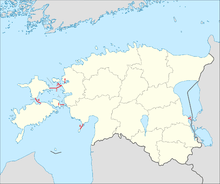

Estonia

The Estonian Road Administration is responsible for managing ice roads in winter. An ice road may be opened when ice thickness is at least 22 cm (8.7 in) along the entire route. An ice road to Piirissaar Island in Lake Peipus is opened in most years, while colder winters permit opening official ice roads on the Baltic Sea between mainland Estonia and the islands of Hiiumaa, Vormsi, Muhu and Kihnu, between the islands of Saaremaa and Hiiumaa and also between Haapsalu and Noarootsi. As of 2011, the longest ice road in Europe is the 26.5 km route between Rohuküla on the continent and Heltermaa in Hiiumaa.[4] The limitations for ice road traffic include:

- Weight limit depending on conditions, mostly 2 t (2.0 long tons; 2.2 short tons) to 2.5 t (2.5 long tons; 2.8 short tons)

- Vehicles travelling in the same direction must be at least 250 m (820 ft) apart.

- Recommended travelling speeds are under 25 km/h (16 mph) or between 40–70 km/h (25–43 mph). It is advised to avoid the range of 25 and 40 km/h (16 and 25 mph) due to danger of creating resonance in the ice layer (i.e. vehicle speed and water wave speed being the same or nearly, resulting in a large wave under the ice that breaks the ice).

- Seat belts must not be fastened and doors must be easily opened, due to danger of drowning if the ice breaks.[5]

- The vehicle must not be stopped.

- Vehicles are allowed to enter the ice road in three-minute intervals.

- Ice roads may only be used in daylight.

Ice road lengths:

- Virtsu – Kuivastu (between the mainland and Muhu) – 9.0 km (5.6 mi)

- Rohuküla – Heltermaa (between the mainland and Hiiumaa) – 26.5 km (16.5 mi)

- Rohuküla – Sviby (between the mainland and Vormsi) – 10.2 km (6.3 mi)

- Tärkma – Triigi (between Hiiumaa and Saaremaa) – 14.5 km (9.0 mi)

- Haapsalu – Noarootsi – 3.2 km (2.0 mi)

- Lao – Kihnu (between the mainland and Kihnu) – 13.0 km (8.1 mi)

Finland

The Finnish Transport Agency maintains some ice roads during winters. These roads are considered as public roads when they are open. The longest 7 km (4.3 mi) road crosses Lake Pielinen.[6] Ice must be at least 40 cm (16 in) thick before the road may be opened. The following limits apply to ice roads:

- Weight limit 3 t (3.0 long tons; 3.3 short tons) (may be raised if ice is thick enough)

- Speed limit 50 km/h (31 mph)

- Minimum space of 50 m (164 ft) between cars traveling in the same direction

- Overtaking is prohibited.

- Stopping is prohibited.

On the severest winters ice roads have been privately constructed from the mainland of Finland to the Åland Islands and elsewhere in the Archipelago; using these is unlikely to be within any insurance policy.

Though it is not allowed to stop on these ice roads, it is common to drive off the road, park the car, and go fishing. Some cottages are also accessed during the winter by ice without any actual ice roads.

Norway

Over the Tana river there are usually two ice roads from December to April. These roads have a weight limit of 2 t (2.0 long tons; 2.2 short tons), but few other limitations. There are numerous ice roads over frozen rivers elsewhere in Norway.

Russia

An example of an ice road was the Road of Life across the frozen Lake Ladoga, which provided the only access to the besieged city of Leningrad in the winter months during World War II.

The Lena River has an ice road on its surface for hundreds of kilometres during the winter.

There are several border crossing points between Russia and China via the Amur River. They are ice roads in the winter months, and ferries during summer.[7][8]

Sweden

In the northern part of Sweden there are many ice roads. The Swedish Road Administration maintains most of them, but some private ice roads also exist. Ice roads are usually put in when ice thickness exceeds 20 cm (7.9 in). The limitations for ice road traffic normally include:

- A speed limit of 30 km/h (19 mph).

- Prohibition against stopping or parking on the ice.

- Minimum distance of 50 m (160 ft) between vehicles.

- Restrictions for axle, bogie and gross weight.

The longest ice road in Sweden, at 15 km (9.3 mi), is in the Luleå Archipelago, Bothnian Bay, in the northernmost part of the Gulf of Bothnia. It starts in the port of Hindersöstallarna and connects the islands Hindersön, Stor-Brändön, and Långön with the mainland. The ice roads in Luleå are usually open from January to April and have a weight restriction of 2–4 t (2.0–3.9 long tons; 2.2–4.4 short tons).

There are several ice roads across the lake Storsjön. The roads are usually open from January to April and have a weight restriction of 2–4 t (2.0–3.9 long tons; 2.2–4.4 short tons).

The southernmost ice road in Sweden is on Lake Hjälmaren, to Vinön Island.[9] Due to poor ice it is not open every season.

As with all ice roads there are periods when there is too much ice for the ferry and too little for the ice road. There has been experiments with pipes blowing compressed air to the bottom, which to some extent prevents ice formation. The ice road has to be placed some distance away from the ferry route. In Sweden there is never more than 80 km (50 mi) detour to use a road with a bridge or around a bay instead of the ferry/ice road, except for some island connections, like the Holmön island, which has a ferry with better ice breaking capabilities.

United States

There is an ice road in the continental United States on Lake Superior, linking the city of Bayfield, Wisconsin on the mainland with La Pointe, Wisconsin on Madeline Island. The road is about 2 mi (3.2 km) long and is used for several weeks in the year as replacement for the summer ferry service. When the ice is too thin to allow the construction of the road, but too thick to allow ferry service, a type of hovercraft is used to transport school children from the island to and from the mainland.[10] In Michigan's Straits of Mackinac, seasonal ice roads also connect Mackinac Island and Bois Blanc Island with the mainland.

In Prudhoe Bay in Alaska, there is an ice road over the Arctic Ocean about 25 mi (40 km) long with a maximum speed of 10 mph (16 km/h). It is used a few months during winter to serve an oil field site on the ocean. Another ice road in Alaska is the ice road from Prudhoe Bay, Alaska to Point Thomson, Alaska. The ice road is 68 mi (109 km) long and is on the Beaufort Sea; this ice road is mainly used by semi-trucks to deliver loads to serve the Point Thomson area.

There is a seasonal ice road constructed from the Kuparuk Oil Field to the Alpine oil field, which is roadless in the summer months. This road also connects to the village of Nuiqsut, on the banks of the Colville River. This road is roughly 31 mi (50 km) long and is used to resupply Alpine with critical supplies for operations as well as to transport drilling rigs.

Media references

The 2008 film Frozen River tells the story of two women who get involved with trafficking illegal immigrants from Canada into the United States by driving them across the frozen St. Lawrence River in their car.

Canada's and Alaska's ice roads were prominently featured in the History Channel show Ice Road Truckers.

See also

References

- Ice Road Truckers

- "Tractor Trains Move Freight in Far North Popular Mechanics, October 1934

- "Riverhurst Crossing" dangerousroads.org

- Estonia claims Europe's longest ice highway. The Independent. 19 February 2011. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- Estonian Road Administration. "Traffic Act | Liiklusseadus 2011". Liiklusseadus 2011. § 65. Archived from the original on 22 March 2016. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

§ 65. Traffic on an ice road

CS1 maint: location (link)

[…]

(4) On an ice road, the doors of a vehicle shall be easily opened.

(5) Every driver and all the passengers shall have their safety belts unfastened.

[…] - Lake Pielinen ice road

- Daniszewaki, John (5 August 2001). "A New Russian Fear -- Losing Siberia To China". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- Lansdell, Henry (2014). Through Siberia. 1. Cambridge University Press. p. 52. ISBN 9781108071222.

- Official message from Vägverket (Sweden) about the ice road in Hjälmaren 2004 Archived 7 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Across the bay, on a school bus wearing skis

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ice roads. |

- Government of NWT Department of Transportation - Ice Roads / Ice Bridges / Winter Roads

- Government of NWT Highway Condition Reports

- Building Canada's Epic Ice Road, Popular Mechanics article.

- 1959 John Denison's Ice Roads NWT Historical Timeline, Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre