Quebec

Quebec (/k(w)ɪˈbɛk/ (![]()

![]()

Quebec Québec (French) | |

|---|---|

| Motto(s): | |

| Coordinates: 52°N 72°W | |

| Country | Canada |

| Confederation | July 1, 1867 (1st, with Ontario, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick) |

| Capital | Quebec City |

| Largest city | Montreal |

| Largest metro | Greater Montreal |

| Government | |

| • Type | Constitutional monarchy |

| • Lieutenant Governor | J. Michel Doyon |

| • Premier | François Legault (CAQ) |

| Legislature | National Assembly of Quebec |

| Federal representation | Parliament of Canada |

| House seats | 78 of 338 (23.1%) |

| Senate seats | 24 of 105 (22.9%) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1,542,056 km2 (595,391 sq mi) |

| • Land | 1,365,128 km2 (527,079 sq mi) |

| • Water | 176,928 km2 (68,312 sq mi) 11.5% |

| Area rank | Ranked 2nd |

| 15.4% of Canada | |

| Population (2016) | |

| • Total | 8,164,361 [1] |

| • Estimate (2020 Q2) | 8,552,362 [2] |

| • Rank | Ranked 2nd |

| • Density | 5.98/km2 (15.5/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | in English: Quebecer or Quebecker, in French: Québécois (m)[3] Québécoise (f)[3] |

| Official languages | French[4] |

| GDP | |

| • Rank | 2nd |

| • Total (2015) | C$380.972 billion[5] |

| • Per capita | C$46,126 (10th) |

| HDI | |

| • HDI (2018) | 0.908[6] — Very high (5th) |

| Time zone | UTC−5, −4 |

| Postal abbr. | QC[7] |

| Postal code prefix | G, H, J |

| ISO 3166 code | CA-QC |

| Flower | Blue flag iris[8] |

| Tree | Yellow birch[8] |

| Bird | Snowy owl[8] |

| Website | www |

| Rankings include all provinces and territories | |

Quebec is the second-most populous province of Canada, after Ontario.[11] It is the only one to have a predominantly French-speaking population, with French as the sole provincial official language. Most inhabitants live in urban areas near the Saint Lawrence River between Montreal and Quebec City, the capital. Approximately half of Quebec residents live in the Greater Montreal Area, including the Island of Montreal. English-speaking communities and English-language institutions are concentrated in the west of the island of Montreal but are also significantly present in the Outaouais, Eastern Townships, and Gaspé regions. The Nord-du-Québec region, occupying the northern half of the province, is sparsely populated and inhabited primarily by Aboriginal peoples.[12]

The climate around the major cities is four-seasons continental with cold and snowy winters combined with warm to hot humid summers, but farther north long winter seasons dominate and as a result the northern areas of the province are marked by tundra conditions.[13] Even in central Quebec, at comparatively southerly latitudes, winters are severe in inland areas.

Quebec independence debates have played a large role in the politics of the province. Parti Québécois governments held referendums on sovereignty in 1980 and 1995. Although neither passed, the 1995 referendum saw the highest voter turnout in Quebec history, at over 93%, and only failed by less than 1%.[14] In 2006, the House of Commons of Canada passed a symbolic motion recognizing the "Québécois as a nation within a united Canada".[15][16]

While the province's substantial natural resources have long been the mainstay of its economy, sectors of the knowledge economy such as aerospace, information and communication technologies, biotechnology, and the pharmaceutical industry also play leading roles. These many industries have all contributed to helping Quebec become an economically influential province within Canada, second only to Ontario in economic output.[17]

Etymology and boundary changes

The name "Québec", which comes from the Algonquin or Ojibwe word kébec meaning "where the river narrows", originally referred to the area around Quebec City where the Saint Lawrence River narrows to a cliff-lined gap. Early variations in the spelling of the name included Québecq (Levasseur, 1601) and Kébec (Lescarbot, 1609).[18] French explorer Samuel de Champlain chose the name Québec in 1608 for the colonial outpost he would use as the administrative seat for the French colony of New France.[19] The province is sometimes referred to as "La belle province" ("The beautiful province").

The Province of Quebec was founded in the Royal Proclamation of 1763 after the Treaty of Paris formally transferred the French colony of Canada[20] to Britain after the Seven Years' War. The proclamation restricted the province to an area along the banks of the Saint Lawrence River. The Quebec Act of 1774 expanded the territory of the province to include the Great Lakes and the Ohio River Valley and south of Rupert's Land, more or less restoring the borders previously existing under French rule before the Conquest of 1760.[21] The Treaty of Paris (1783) ceded territories south of the Great Lakes to the United States.[22] After the Constitutional Act of 1791, the territory was divided between Lower Canada (present-day Quebec) and Upper Canada (present-day Ontario), with each being granted an elected legislative assembly.[23] In 1840, these become Canada East and Canada West after the British Parliament unified Upper and Lower Canada into the Province of Canada.[24] This territory was redivided into the Provinces of Quebec and Ontario at Confederation in 1867.[25] Each became one of the first four provinces.

In 1870, Canada purchased Rupert's Land from the Hudson's Bay Company and over the next few decades the Parliament of Canada transferred to Quebec portions of this territory that would more than triple the size of the province.[26] In 1898, the Canadian Parliament passed the first Quebec Boundary Extension Act that expanded the provincial boundaries northward to include the lands of the local aboriginal peoples.[27] This was followed by the addition of the District of Ungava through the Quebec Boundaries Extension Act of 1912 that added the northernmost lands of the Inuit to create the modern Province of Quebec.[27] In 1927, the border between Quebec and Newfoundland and Labrador was established by the British Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. Quebec officially disputes this boundary.[28]

Geography

Located in the eastern part of Canada, and (from a historical and political perspective) part of Central Canada, Quebec occupies a territory nearly three times the size of France or Texas, most of which is very sparsely populated.[29] Its topography is very different from one region to another due to the varying composition of the ground, the climate (latitude and altitude), and the proximity to water. The Saint Lawrence Lowland and the Appalachians are the two main topographic regions in southern Quebec, while the Canadian Shield occupies most of central and northern Quebec.[30]

Hydrography

Quebec has one of the world's largest reserves of fresh water,[31] occupying 12% of its surface.[32] It has 3% of the world's renewable fresh water, whereas it has only 0.1% of its population.[33] More than half a million lakes,[31] including 30 with an area greater than 250 square kilometres (97 sq mi), and 4,500 rivers[31] pour their torrents into the Atlantic Ocean, through the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and the Arctic Ocean, by James, Hudson, and Ungava bays. The largest inland body of water is the Caniapiscau Reservoir, created in the realization of the James Bay Project to produce hydroelectric power. Lake Mistassini is the largest natural lake in Quebec.[34]

The Saint Lawrence River has some of the world's largest sustaining inland Atlantic ports at Montreal (the province's largest city), Trois-Rivières, and Quebec City (the capital). Its access to the Atlantic Ocean and the interior of North America made it the base of early French exploration and settlement in the 17th and 18th centuries. Since 1959, the Saint Lawrence Seaway has provided a navigable link between the Atlantic Ocean and the Great Lakes. Northeast of Quebec City, the river broadens into the world's largest estuary, the feeding site of numerous species of whales, fish, and seabirds.[35] The river empties into the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. This marine environment sustains fisheries and smaller ports in the Lower Saint Lawrence (Bas-Saint-Laurent), Lower North Shore (Côte-Nord), and Gaspé (Gaspésie) regions of the province. The Saint Lawrence River with its estuary forms the basis of Quebec's development through the centuries. Other notable rivers include the Ashuapmushuan, Chaudière, Gatineau, Manicouagan, Ottawa, Richelieu, Rupert, Saguenay, Saint-François, and Saint-Maurice.

Topography

Quebec's highest point at 1,652 metres is Mont d'Iberville, known in English as Mount Caubvick, located on the border with Newfoundland and Labrador in the northeastern part of the province, in the Torngat Mountains.[36] The most populous physiographic region is the Saint Lawrence Lowland. It extends northeastward from the southwestern portion of the province along the shores of the Saint Lawrence River to the Quebec City region, limited to the North by the Laurentian Mountains and to the South by the Appalachians. It mainly covers the areas of the Centre-du-Québec, Laval, Montérégie and Montreal, the southern regions of the Capitale-Nationale, Lanaudière, Laurentides, Mauricie and includes Anticosti Island, the Mingan Archipelago,[37] and other small islands of the Gulf of St. Lawrence lowland forests ecoregion.[38] Its landscape is low-lying and flat, except for isolated igneous outcrops near Montreal called the Monteregian Hills, formerly covered by the waters of Lake Champlain. The Oka hills also rise from the plain. Geologically, the lowlands formed as a rift valley about 100 million years ago and are prone to infrequent but significant earthquakes.[30] The most recent layers of sedimentary rock were formed as the seabed of the ancient Champlain Sea at the end of the last ice age about 14,000 years ago.[39] The combination of rich and easily arable soils and Quebec's relatively warm climate makes this valley the most prolific agricultural area of Quebec province. Mixed forests provide most of Canada's springtime maple syrup crop. The rural part of the landscape is divided into narrow rectangular tracts of land that extend from the river and date back to settlement patterns in 17th century New France.

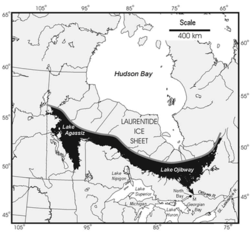

More than 95% of Quebec's territory lies within the Canadian Shield.[40] It is generally a quite flat and exposed mountainous terrain interspersed with higher points such as the Laurentian Mountains in southern Quebec, the Otish Mountains in central Quebec and the Torngat Mountains near Ungava Bay. The topography of the Shield has been shaped by glaciers from the successive ice ages, which explains the glacial deposits of boulders, gravel and sand, and by sea water and post-glacial lakes that left behind thick deposits of clay in parts of the Shield. The Canadian Shield also has a complex hydrological network of perhaps a million lakes, bogs, streams and rivers. It is rich in the forestry, mineral and hydro-electric resources that are a mainstay of the Quebec economy. Primary industries sustain small cities in regions of Abitibi-Témiscamingue, Saguenay–Lac-Saint-Jean, and Côte-Nord.

The Labrador Peninsula is covered by the Laurentian Plateau (or Canadian Shield), dotted with mountains such as Otish Mountains. The Ungava Peninsula is notably composed of D'Youville mountains, Puvirnituq mountains and Pingualuit crater. While low and medium altitude peak from western Quebec to the far north, high altitudes mountains emerge in the Capitale-Nationale region to the extreme east, along its longitude. In the Labrador Peninsula portion of the Shield, the far northern region of Nunavik includes the Ungava Peninsula and consists of flat Arctic tundra inhabited mostly by the Inuit. Further south lie the subarctic taiga of the Eastern Canadian Shield taiga ecoregion and the boreal forest of the Central Canadian Shield forests, where spruce, fir, and poplar trees provide raw materials for Quebec's pulp and paper and lumber industries. Although the area is inhabited principally by the Cree, Naskapi, and Innu First Nations, thousands of temporary workers reside at Radisson to service the massive James Bay Hydroelectric Project on the La Grande and Eastmain rivers. The southern portion of the shield extends to the Laurentians, a mountain range just north of the Saint Lawrence Lowland, that attracts local and international tourists to ski hills and lakeside resorts.

The Appalachian region of Quebec has a narrow strip of ancient mountains along the southeastern border of Quebec. The Appalachians are actually a huge chain that extends from Alabama to Newfoundland. In between, it covers in Quebec near 800 km (497 mi), from the Montérégie hills to the Gaspé Peninsula. In western Quebec, the average altitude is about 500 metres, while in the Gaspé Peninsula, the Appalachian peaks (especially the Chic-Choc) are among the highest in Quebec, exceeding 1000 metres.

Climate

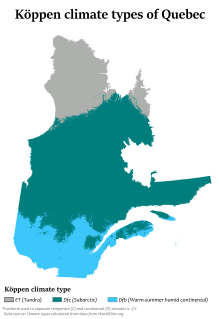

In general, the climate of Quebec is cold and humid.[41] The climate of the province is largely determined by its latitude, maritime and elevation influences.[41] According to the Köppen climate classification, Quebec has three main climate regions.[41] Southern and western Quebec, including most of the major population centres and areas south of 51oN, have a humid continental climate (Köppen climate classification Dfb) with four distinct seasons having warm to occasionally hot and humid summers and often very cold and snowy winters.[41][42] The main climatic influences are from western and northern Canada and move eastward, and from the southern and central United States that move northward. Because of the influence of both storm systems from the core of North America and the Atlantic Ocean, precipitation is abundant throughout the year, with most areas receiving more than 1,000 millimetres (39 in) of precipitation, including over 300 centimetres (120 in) of snow in many areas.[43] During the summer, severe weather patterns (such as tornadoes and severe thunderstorms) occur occasionally.[44] Most of central Quebec, ranging from 51 to 58 degrees North has a subarctic climate (Köppen Dfc).[41] Winters are long, very cold, and snowy, and among the coldest in eastern Canada, while summers are warm but very short due to the higher latitude and the greater influence of Arctic air masses. Precipitation is also somewhat less than farther south, except at some of the higher elevations. The northern regions of Quebec have an arctic climate (Köppen ET), with very cold winters and short, much cooler summers.[41] The primary influences in this region are the Arctic Ocean currents (such as the Labrador Current) and continental air masses from the High Arctic.

The four calendar seasons in Quebec are spring, summer, autumn and winter, with conditions differing by region. They are then differentiated according to the insolation, temperature, and precipitation of snow and rain.[45]

At Quebec City, the length of the daily sunshine varies from 8:37 hrs in December to 15:50 hrs in June; the annual variation is much greater (from 4:54 to 19:29 hrs) at the northern tip of the province.[46] From temperate zones to the northern territories of the Far North, the brightness varies with latitude, as well as the Northern Lights and midnight sun.

Quebec is divided into four climatic zones: arctic, subarctic, humid continental and East maritime. From south to north, average temperatures range in summer between 25 and 5 °C (77 and 41 °F) and, in winter, between −10 and −25 °C (14 and −13 °F).[47][48] In periods of intense heat and cold, temperatures can reach 35 °C (95 °F) in the summer[49] and −40 °C (−40 °F) during the Quebec winter,[49] They may vary depending on the Humidex or Wind chill. The all time record high was 40.0 °C (104.0 °F) and the all time record low was −51.0 °C (−59.8 °F).[50]

The all-time record of the greatest precipitation in winter was established in winter 2007–2008, with more than five metres[51] of snow in the area of Quebec City, while the average amount received per winter is around three metres.[52] March 1971, however, saw the "Century's Snowstorm" with more than 40 centimetres (16 in) in Montreal to 80 centimetres (31 in) in Mont Apica of snow within 24 hours in many regions of southern Quebec. Also, the winter of 2010 was the warmest and driest recorded in more than 60 years.[53]

| Location | July (°C) | July (°F) | January (°C) | January (°F) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Montreal | 26/16 | 79/61 | −5/−14 | 22/7 |

| Gatineau | 26/15 | 79/60 | −6/−15 | 21/5 |

| Quebec City | 25/13 | 77/56 | −8/−18 | 17/0 |

| Trois-Rivières | 25/14 | 78/58 | −7/−17 | 19/1 |

| Sherbrooke | 24/11 | 76/53 | −6/−18 | 21/0 |

| Saguenay | 24/12 | 75/54 | −10/−21 | 14/−6 |

| Matagami | 23/9 | 73/48 | −13/−26 | 8/−16 |

| Kuujjuaq | 17/6 | 63/43 | −20/−29 | −4/−20 |

| Inukjuak | 13/5 | 56/42 | −21/−28 | −6/−19 |

Wildlife

The large land wildlife is mainly composed of the white-tailed deer, the moose, the muskox, the caribou, the American black bear and the polar bear. The average land wildlife includes the cougar, the coyote, the eastern wolf, the bobcat, the Arctic fox, the fox, etc. The small animals seen most commonly include the eastern grey squirrel, the snowshoe hare, the groundhog, the skunk, the raccoon, the chipmunk and the Canadian beaver.

Biodiversity of the estuary and gulf of Saint Lawrence River[55] consists of an aquatic mammal wildlife, of which most goes upriver through the estuary and the Saguenay–St. Lawrence Marine Park until the Île d'Orléans (French for Orleans Island), such as the blue whale, the beluga, the minke whale and the harp seal (earless seal). Among the Nordic marine animals, there are two particularly important to cite: the walrus and the narwhal.[56]

Inland waters are populated by small to large fresh water fish, such as the largemouth bass, the American pickerel, the walleye, the Acipenser oxyrinchus, the muskellunge, the Atlantic cod, the Arctic char, the brook trout, the Microgadus tomcod (tomcod), the Atlantic salmon, the rainbow trout, etc.[57]

Among the birds commonly seen in the southern inhabited part of Quebec, there are the American robin, the house sparrow, the red-winged blackbird, the mallard, the common grackle, the blue jay, the American crow, the black-capped chickadee, some warblers and swallows, the starling and the rock pigeon, the latter two having been introduced in Quebec and are found mainly in urban areas.[58] Avian fauna includes birds of prey like the golden eagle, the peregrine falcon, the snowy owl and the bald eagle. Sea and semi-aquatic birds seen in Quebec are mostly the Canada goose, the double-crested cormorant, the northern gannet, the European herring gull, the great blue heron, the sandhill crane, the Atlantic puffin and the common loon.[59] Many more species of land, maritime or avian wildlife are seen in Quebec, but most of the Quebec-specific species and the most commonly seen species are listed above.

Some livestock have the title of "Québec heritage breed", namely the Canadian horse, the Chantecler chicken and the Canadian cow.[60] Moreover, in addition to food certified as "organic", Charlevoix lamb is the first local Quebec product whose geographical indication is protected.[61] Livestock production also includes the pig breeds Landrace, Duroc and Yorkshire[62] and many breeds of sheep[63] and cattle.

The Wildlife Foundation of Quebec and the Data Centre on Natural Heritage of Quebec (CDPNQ)(French acronym)[64] are the main agencies working with officers for wildlife conservation in Quebec.

Vegetation

Given the geology of the province and its different climates, there is an established number of large areas of vegetation in Quebec. These areas, listed in order from the northernmost to the southernmost are: the tundra, the taiga, the Canadian boreal forest (coniferous), mixed forest and Deciduous forest.[40]

On the edge of the Ungava Bay and Hudson Strait is the tundra, whose flora is limited to a low vegetation of lichen with only less than 50 growing days a year. The tundra vegetation survives an average annual temperature of −8 °C (18 °F). The tundra covers more than 24% of the area of Quebec.[40] Further south, the climate is conducive to the growth of the Canadian boreal forest, bounded on the north by the taiga.

Not as arid as the tundra, the taiga is associated with the sub-Arctic regions of the Canadian Shield[65] and is characterized by a greater number of both plant (600) and animal (206) species, many of which live there all year. The taiga covers about 20% of the total area of Quebec.[40] The Canadian boreal forest is the northernmost and most abundant of the three forest areas in Quebec that straddle the Canadian Shield and the upper lowlands of the province. Given a warmer climate, the diversity of organisms is also higher, since there are about 850 plant species and 280 vertebrates species. The Canadian boreal forest covers 27% of the area of Quebec.[40] The mixed forest is a transition zone between the Canadian boreal forest and deciduous forest. By virtue of its transient nature, this area contains a diversity of habitats resulting in large numbers of plant (1000) and vertebrates (350) species, despite relatively cool temperatures. The ecozone mixed forest covers 11.5% of the area of Quebec and is characteristic of the Laurentians, the Appalachians and the eastern lowlands forests.[65] The third most northern forest area is characterized by deciduous forests. Because of its climate (average annual temperature of 7 °C (45 °F)), it is in this area that one finds the greatest diversity of species, including more than 1600 vascular plants and 440 vertebrates. Its relatively long growing season lasts almost 200 days and its fertile soils make it the centre of agricultural activity and therefore of urbanization of Quebec. Most of Quebec's population lives in this area of vegetation, almost entirely along the banks of the St. Lawrence. Deciduous forests cover approximately 6.6% of the area of Quebec.[40]

The total forest area of Quebec is estimated at 750,300 square kilometres (289,700 sq mi).[66] From the Abitibi-Témiscamingue to the North Shore, the forest is composed primarily of conifers such as the Abies balsamea, the jack pine, the white spruce, the black spruce and the tamarack. Some species of deciduous trees such as the yellow birch appear when the river is approached in the south. The deciduous forest of the Saint Lawrence Lowlands is mostly composed of deciduous species such as the sugar maple, the red maple, the white ash, the American beech, the butternut (white walnut), the American elm, the basswood, the bitternut hickory and the northern red oak as well as some conifers such as the eastern white pine and the northern whitecedar. The distribution areas of the paper birch, the trembling aspen and the mountain ash cover more than half of Quebec territory.[67]

History

Indigenous peoples and European exploration

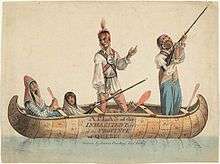

At the time of first European contact and later colonization, Algonquian, Iroquois and Inuit nations controlled what is now Quebec.[68] Their lifestyles and cultures reflected the land on which they lived. Algonquians organized into seven political entities lived nomadic lives based on hunting, gathering, and fishing in the rugged terrain of the Canadian Shield (James Bay Cree, Innu, Algonquins) and Appalachian Mountains (Mi'kmaq, Abenaki).[69] St. Lawrence Iroquoians, a branch of the Iroquois, lived more settled lives, growing corn, beans and squash in the fertile soils of the St. Lawrence Valley. They appear to have been later supplanted by the Mohawk nation.[70] The Inuit continue to fish and hunt whale and seal in the harsh Arctic climate along the coasts of Hudson and Ungava Bay.[71] These people traded fur and food and sometimes warred with each other.

New France

Around 1522–1523, the Italian navigator Giovanni da Verrazzano persuaded King Francis I of France to commission an expedition to find a western route to Cathay (China). In 1534, Breton explorer Jacques Cartier planted a cross in the Gaspé Peninsula and claimed the land in the name of King Francis I.[73] It was the first province of New France. However, initial French attempts at settling the region met with failure.[73] French fishing fleets, however, continued to sail to the Atlantic coast and into the St. Lawrence River, making alliances with First Nations that would become important once France began to occupy the land.[74]

Samuel de Champlain was part of a 1603 expedition from France that travelled into the St. Lawrence River.[75] In 1608, he returned as head of an exploration party and founded Quebec City with the intention of making the area part of the French colonial empire.[76][77][78] Champlain's Habitation de Québec, built as a permanent fur trading outpost, was where he would forge a trading, and ultimately a military alliance, with the Algonquin and Huron nations.[79] First Nations traded their furs for many French goods such as metal objects, guns, alcohol, and clothing.

Coureurs des bois, voyageurs and Catholic missionaries used river canoes to explore the interior of the North American continent.[80] They established fur trading forts on the Great Lakes (Étienne Brûlé 1615), Hudson Bay (Radisson and Groseilliers 1659–60), Ohio River and Mississippi River (La Salle 1682), as well as the Saskatchewan River and Missouri River (de la Verendrye 1734–1738).[81]

After 1627, King Louis XIII of France allowed the Company of New France to introduced the seigneurial system and forbade settlement in New France by anyone other than Roman Catholics.[82]

In 1629 there was the surrender of Quebec, without battle, to English privateers led by David Kirke during the Anglo-French War. However, Samuel de Champlain argued that the English seizing of the lands was illegal as the war had already ended; he worked to have the lands returned to France. As part of the ongoing negotiations of their exit from the Anglo-French War, in 1632 the English king Charles agreed to return the lands in exchange for Louis XIII paying his wife's dowry. These terms were signed into law with the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye. The lands in Quebec and Acadia were returned to the French Company of One Hundred Associates.

New France became a Royal Province in 1663 under King Louis XIV of France with a Sovereign Council that included intendant Jean Talon.[83] The population grew slowly under French rule,[84] thus remained relatively low as growth was largely achieved through natural births, rather than by immigration.[85] To encourage population growth and to redress the severe imbalance between single men and women, King Louis XIV sponsored the passage of approximately 800 young French women (known as les filles du roi) to the colony. Most of the French were farmers ("Canadiens" or "Habitants"), and the rate of population growth among the settlers themselves was very high.[86]

Seven Years' War and capitulation of New France

Authorities in New France became more aggressive in their efforts to expel British traders and colonists from the Ohio Valley. They began construction of a series of fortifications to protect the area.[87] In 1754, George Washington launched a surprise attack on a group of Canadian soldiers sleeping in the early morning hours. It came at a time when no declaration of war had been issued by either country. This frontier aggression known as the Jumonville affair set the stage for the French and Indian War (a US designation; in Canada it is usually referred to as the Seven Years' War, although French Canadians often call it La guerre de la Conquête ["The War of Conquest"][88][89]) in North America. By 1756, France and Britain were battling the Seven Years' War worldwide. In 1758, the British mounted an attack on New France by sea and took the French fort at Louisbourg.

On September 13, 1759, the British forces of General James Wolfe defeated those of French General Louis-Joseph de Montcalm on the Plains of Abraham outside Quebec City. With the exception of the small islands of Saint Pierre and Miquelon, located off the coast of Newfoundland, France ceded its North American possessions to Great Britain through the Treaty of Paris (1763) in favour of gaining the island of Guadeloupe for its then-lucrative sugar cane industry.[90] The British Royal Proclamation of 1763 renamed Canada (part of New France) as the Province of Quebec.

Quebec Act

With unrest growing in the colonies to the south, which would one day grow into the American Revolution, the British were worried that the French-speaking Canadians might also support the growing rebellion. At that time, French-speaking Canadians formed the vast majority of the population of the province of Quebec (more than 99%) and British immigration was not going well. To secure the allegiance of the approximately 90,000 French-speaking Canadians to the British crown, first Governor James Murray and later Governor Guy Carleton promoted the need for change. There was also a need to compromise between the conflicting demands of the French-speaking Canadian subjects and those of newly arrived British subjects. These efforts by the colonial governors eventually resulted in enactment of the Quebec Act[91] of 1774.

The Quebec Act provided the people of Quebec their first Charter of Rights and paved the way to later official recognition of the French language and French culture. The act also allowed the French speakers, known as Canadiens, to maintain French civil law and sanctioned freedom of religion, allowing the Roman Catholic Church to remain, one of the first cases in history of state-sanctioned freedom of religious practice.[92]

Effects of the American Revolution

Although the Quebec Act was unrelated to the events in Boston of 1773, and was not regarded as one of the Coercive Acts, the timing of its passage led British colonists to the south to believe that it was part of the program to punish them. The Quebec Act offended a variety of interest groups in the British colonies. Land speculators and settlers objected to the transfer of western lands previously claimed by the colonies to a non-representative government. Many feared the establishment of Catholicism in Quebec, and that the French Canadians were being courted to help oppress British Americans.[93]

On June 27, 1775, General George Washington and his Continental Army invaded Canada in an attempt to conquer Quebec. British reinforcements came up the St. Lawrence in May 1776, and the Battle of Trois-Rivières turned into a disaster for the Americans. The army withdrew to Ticonderoga.[94] Although some help was given to the Americans by the locals, Governor Carleton punished American sympathizers, and public support of the American cause came to an end. In 1778, Frederick Haldimand took over for Guy Carleton as governor of Quebec.

The arrival of 10,000 Loyalists at Quebec in 1784 destroyed the political balance that Haldimand (and Carleton before him) had worked so hard to achieve. The swelling numbers of English encouraged them to make greater demands for recognition with the colonial government.[95] To restore stability to his largest remaining North American colony, King George III sent Carleton back to Quebec to remedy the situation.[96]

In ten years, Quebec had undergone a dramatic change. What worked for Carleton in 1774 was not likely to succeed in 1784. Specifically, there was no possibility of restoring the previous political balance – there were simply too many English people unwilling to reach a compromise with the 145,000 Canadiens or their colonial governor. The situation called for a more creative approach to problem solving.[96]

Separation of the Province of Quebec

Loyalists soon petitioned the government to be allowed to use the British legal system they were used to in the American colonies. The creation of Upper and Lower Canada in 1791 allowed most Loyalists to live under British laws and institutions, while the French-speaking population of Lower Canada could maintain their familiar French civil law and the Catholic religion.[97] Therefore, Governor Haldimand (at the suggestion of Carleton) drew Loyalists away from Quebec City and Montreal by offering free land on the northern shore of Lake Ontario to anyone willing to swear allegiance to George III. The Loyalists were thus given land grants of 200 acres (81 ha) per person. Basically, this approach was designed with the intent of keeping French and English as far apart as possible. Therefore, after the separation of the Province of Quebec, Lower Canada and Upper Canada were formed, each with its own government.[96]

Rebellion in Lower Canada

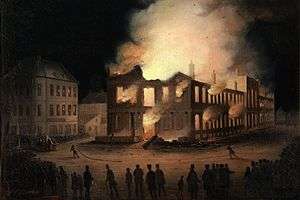

In 1837, residents of Lower Canada – led by Louis-Joseph Papineau and Robert Nelson – formed an armed resistance group to seek an end to the unilateral control of the British governors.[98] They made a Declaration of Rights with equality for all citizens without discrimination and a Declaration of Independence of Lower Canada in 1838.[99] Their actions resulted in rebellions in both Lower and Upper Canada. An unprepared British Army had to raise militia force; the rebel forces scored a victory in Saint-Denis but were soon defeated.

After the rebellions, Lord Durham was asked to undertake a study and prepare a report on the matter and to offer a solution for the British Parliament to assess.[100] Following Durham's report,[100] the British government merged the two colonial provinces into one Province of Canada in 1840 with the Act of Union.[101] The two colonies remained distinct in administration, election, and law.

In 1848, Baldwin and LaFontaine, allies and leaders of the Reformist party, were asked by Lord Elgin to form an administration together under the new policy of responsible government. The French language subsequently regained legal status in the Legislature.[101]

Canadian Confederation

In the 1860s, the delegates from the colonies of British North America (Canada, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland) met in a series of conferences to discuss self-governing status for a new confederation. The first Charlottetown Conference took place in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, followed by the Quebec Conference in Quebec City which led to a delegation going to London, England, to put forth a proposal for a national union.[102]

As a result of those deliberations, in 1867 the Parliament of the United Kingdom passed the British North America Acts, providing for the Confederation of most of these provinces. The former Province of Canada was divided into its two previous parts as the provinces of Ontario (Upper Canada) and Quebec (Lower Canada). New Brunswick and Nova Scotia joined Ontario and Quebec in the new Dominion of Canada. The other provinces then joined Confederation, one after the other: Manitoba and the Northwest Territories in 1870, British Columbia in 1871, Prince Edward Island in 1873, Yukon in 1898, Alberta and Saskatchewan in 1905, Newfoundland in 1949 and finally Nunavut in 1999.[103]

World War I and World War II

When Great Britain declared war on August 4, 1914, Canada was automatically involved as a dominion. About 6,000 volunteers from Quebec participated on the European front. Although reaction to conscription was favourable in English Canada the idea was deeply unpopular in Quebec. The Conscription Crisis of 1917 did much to highlight the divisions between French and English-speaking Canadians in Canada.

During World War II, the participation of Quebec was more important but led to the Conscription Crisis of 1944 and opposition. Many Quebecers fought against the axis powers between 1939 to 1945 with the involvement of many francophone regiments such as Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal, le Régiment de la Chaudière and many more.

Quiet Revolution

The conservative government of Maurice Duplessis and his Union Nationale dominated Quebec politics from 1944 to 1959 with the support of the Catholic Church.[104] Pierre Trudeau and other liberals formed an intellectual opposition to Duplessis's regime, setting the groundwork for the Quiet Revolution under Jean Lesage's Liberals. The Quiet Revolution was a period of dramatic social and political change[105] that saw the decline of Anglo supremacy in the Quebec economy, the decline of the Roman Catholic Church's influence,[14] the formation of hydroelectric companies under Hydro-Québec[105] and the emergence of a pro-sovereignty movement under former Liberal minister René Lévesque.

October Crisis

Beginning in 1963, a paramilitary group that became known as the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ) launched a decade-long programme of propaganda and terrorism that included bombings, robberies and attacks[106] directed primarily at English institutions, resulting in at least five deaths. In 1970, their activities culminated in events referred to as the October Crisis when James Cross, the British trade commissioner to Canada, was kidnapped along with Pierre Laporte, a provincial minister and Vice-Premier.[107] Laporte was strangled with his own rosary beads a few days later. In their published Manifesto, the militants stated: "In the coming year Bourassa will have to face reality; 100,000 revolutionary workers, armed and organized." At the request of Premier Robert Bourassa, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau invoked the War Measures Act.

Parti Québécois and national unity

In 1977, the newly elected Parti Québécois government of René Lévesque introduced the Charter of the French Language. Often known as Bill 101, it defined French as the only official language of Quebec in areas of provincial jurisdiction.[108]

Lévesque and his party had run in the 1970 and 1973 Quebec elections under a platform of separating Quebec from the rest of Canada. The party failed to win control of Quebec's National Assembly both times – though its share of the vote increased from 23 percent to 30 percent – and Lévesque was defeated both times in the riding he contested.[109] In the 1976 election campaign, he softened his message by promising a referendum (plebiscite) on sovereignty-association rather than outright separation, by which Quebec would have independence in most government functions but share some other ones, such as a common currency, with Canada. On November 15, 1976, Lévesque and the Parti Québécois won control of the provincial government for the first time. The question of sovereignty-association was placed before the voters in the 1980 Quebec referendum. During the campaign, Pierre Trudeau promised that a vote for the "no" side was a vote for reforming Canada. Trudeau advocated the patriation of Canada's Constitution from the United Kingdom. The existing constitutional document, the British North America Act, could only be amended by the United Kingdom Parliament upon a request by the Canadian parliament.

Sixty percent of the Quebec electorate voted against the proposition for sovereignty-association.[110] Polls showed that the overwhelming majority of English and immigrant Quebecers voted against, and that French Quebecers were almost equally divided, with older voters less in favour and younger voters more in favour. After his loss in the referendum, Lévesque went back to Ottawa to start negotiating a new constitution with Trudeau, his minister of Justice Jean Chrétien and the nine other provincial premiers. Lévesque insisted Quebec be able to veto any future constitutional amendments. The negotiations quickly reached a stand-still. Quebec is the only province not to have assented to the patriation of the Canadian constitution in 1982.[111]

In subsequent years, two attempts were made to gain Quebec's approval of the constitution. The first was the Meech Lake Accord of 1987, which was finally abandoned in 1990 when the province of Manitoba did not pass it within the established deadline. (Newfoundland premier Clyde Wells had expressed his opposition to the accord, but, with the failure in Manitoba, the vote for or against Meech never took place in his province.) This led to the formation of the sovereigntist Bloc Québécois party in Ottawa under the leadership of Lucien Bouchard,[112] who had resigned from the federal cabinet. The second attempt, the Charlottetown Accord of 1992, also failed to gain traction. This result caused a split in the Quebec Liberal Party that led to the formation of the new Action démocratique (Democratic Action) party led by Mario Dumont and Jean Allaire.

On October 30, 1995, with the Parti Québécois back in power since 1994, a second referendum on sovereignty took place. This time, it was rejected by a slim majority (50.6 percent NO to 49.4 percent YES).[113]

Statut particulier ("special status")

Given the province's heritage and the preponderance of French (unique among the Canadian provinces), there has been debate in Canada regarding the unique status (statut particulier) of Quebec and its people, wholly or partially. Prior attempts to amend the Canadian constitution to acknowledge Quebec as a "distinct society" – referring to the province's uniqueness within Canada regarding law, language, and culture – have been unsuccessful; however, the federal government under Prime Minister Jean Chrétien would later endorse recognition of Quebec as a distinct society.[114]

On October 30, 2003, the National Assembly of Quebec voted unanimously to affirm "that the people of Québec form a nation".[115] On November 27, 2006, the House of Commons passed a symbolic motion moved by Prime Minister Stephen Harper declaring "that this House recognize that the Québécois form a nation within a united Canada."[116][117][118] However, there is considerable debate and uncertainty over what this means.[119][120]

Government and politics

.jpg)

The Lieutenant Governor represents the Queen of Canada and acts as the province's head of state.[121][122] The head of government is the premier (called premier ministre in French) who leads the largest party in the unicameral National Assembly, or Assemblée Nationale, from which the Executive Council of Quebec is appointed.

Until 1968, the Quebec legislature was bicameral,[123] consisting of the Legislative Council and the Legislative Assembly. In that year, the Legislative Council was abolished and the Legislative Assembly was renamed the National Assembly. Quebec was the last province to abolish its legislative council.

The government of Quebec awards an order of merit called the National Order of Quebec. It is inspired in part by the French Legion of Honour. It is conferred upon men and women born or living in Quebec (but non-Quebecers can be inducted as well) for outstanding achievements.[124]

The government of Quebec takes the majority of its revenue through a progressive income tax, a 9.975% sales tax[125] and various other taxes (such as carbon, corporate and capital gains taxes), equalization payments from the federal government, transfer payments from other provinces and direct payments.[126] By some measures Quebec is the highest taxed province;[127] a 2012 study indicated that "Quebec companies pay 26 per cent more in taxes than the Canadian average".[128] A 2014 report by the Fraser Institute indicated that "Relative to its size, Quebec is the most indebted province in Canada by a wide margin".[129]

Administrative subdivisions

Quebec has subdivisions at the regional, supralocal and local levels. Excluding administrative units reserved for Aboriginal lands, the primary types of subdivision are:

At the regional level:

- 17 administrative regions.

At the supralocal level:

- 86 regional county municipalities or RCMs (municipalités régionales de comté, MRC);

- 2 metropolitan communities (communautés métropolitaines).

At the local level:

Demographics

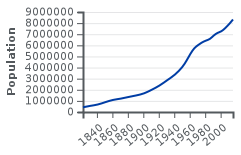

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1831 | 553,134 | — |

| 1841 | 650,000 | +17.5% |

| 1851 | 892,061 | +37.2% |

| 1861 | 1,111,566 | +24.6% |

| 1871 | 1,191,516 | +7.2% |

| 1881 | 1,359,027 | +14.1% |

| 1891 | 1,488,535 | +9.5% |

| 1901 | 1,648,898 | +10.8% |

| 1911 | 2,005,776 | +21.6% |

| 1921 | 2,360,665 | +17.7% |

| 1931 | 2,874,255 | +21.8% |

| 1941 | 3,331,882 | +15.9% |

| 1951 | 4,055,681 | +21.7% |

| 1956 | 4,628,378 | +14.1% |

| 1961 | 5,259,211 | +13.6% |

| 1966 | 5,780,845 | +9.9% |

| 1971 | 6,027,765 | +4.3% |

| 1976 | 6,234,445 | +3.4% |

| 1981 | 6,438,403 | +3.3% |

| 1986 | 6,532,460 | +1.5% |

| 1991 | 6,895,963 | +5.6% |

| 1996 | 7,138,795 | +3.5% |

| 2001 | 7,237,479 | +1.4% |

| 2006 | 7,546,131 | +4.3% |

| 2011 | 7,903,001 | +4.7% |

| 2016 | 8,164,361 | +3.3% |

| Source: Statistics Canada[130][131] | ||

In the 2016 census, Quebec had a population of 8,164,361 living in 3,531,663 of its 3,858,943 total dwellings, a 3.3% change from its 2011 population of 7,903,001. With a land area of 1,356,625.27 km2 (523,795.95 sq mi), it had a population density of 6.0/km2 (15.6/sq mi) in 2016.[1] In 2013, Statistics Canada estimated the province's population to be 8,155,334.[132]

At 1.69 children per woman, Quebec's 2011 fertility rate is above the Canada-wide rate of 1.61,[133] and is higher than it was at the turn of the 21st century. However, it is still below the replacement fertility rate of 2.1. This contrasts with its fertility rates before 1960, which were among the highest of any industrialized society. Although Quebec is home to only 24% of the population of Canada, the number of international adoptions in Quebec is the highest of all provinces of Canada. In 2001, 42% of international adoptions in Canada were carried out in Quebec. By 2012, the population of Quebec reached 8 million, and it is projected to reach 9.2 million in 2056.[134] Life expectancy in Quebec reached a new high in 2011, with an expectancy of 78.6 years for men and 83.2 years for women; this ranked as the third-longest life expectancy among Canadian provinces, behind those of British Columbia and Ontario.[133]

All the tables in the following section have been reduced from their original size, for full tables see main article Demographics of Quebec.

Origins in this table are self-reported and respondents were allowed to give more than one answer.

| Ethnic origin | Population | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Canadian (Canadiens) | 4,474,115 | 60% |

| French | 2,151,655 | 29% |

| Irish | 406,085 | 5.5% |

| Italian | 299,655 | 4% |

| English | 245,155 | 3.3% |

| First Nations | 219,815 | 3% |

| Scottish | 202,515 | 2.7% |

| Québécois | 140,075 | 2% |

| German | 131,795 | 1.8% |

Percentages are calculated as a proportion of the total number of respondents (7,435,905) and may total more than 100 percent due to dual responses.

Only groups with 1.5 percent or more of respondents are shown.[135]

The 2006 census counted a total aboriginal population of 108,425 (1.5 percent) including 65,085 North American Indians (0.9 percent), 27,985 Métis (0.4 percent), and 10,950 Inuit (0.15 percent). There is a significant undercount, as many of the largest Indian bands regularly refuse to participate in Canadian censuses for political reasons regarding the question of aboriginal sovereignty. In particular, the largest Mohawk Iroquois reserves (Kahnawake, Akwesasne and Kanesatake) were not counted.

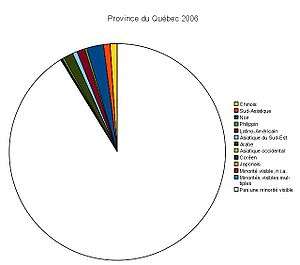

Nearly 9% of the population of Quebec belongs to a visible minority group. This is a lower percentage than that of British Columbia, Ontario, Alberta, and Manitoba but higher than that of the other five provinces. Most visible minorities in Quebec live in or near Montreal.

| Visible minority | Population | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Total visible minority population | 654,355 | 8.8% |

| Haitian | 188,070 | 2.5% |

| Arab | 109,020 | 1.5% |

| Latin American | 89,505 | 1.2% |

| Chinese | 79,830 | 1.1% |

| South Asian | 72,845 | 1.0% |

| Southeast Asian | 50,455 | 0.7% |

Percentages are calculated as a proportion of the total number of respondents (7,435,905).

Only groups with more than 0.5 percent of respondents are shown.[136]

Religion

Quebec is unique among the provinces in its overwhelmingly Roman Catholic population, though recently with a low church attendance. This is a legacy of colonial times when only Roman Catholics were permitted to settle in New France. The 2001 census showed the population to be 90.3 percent Christian (in contrast to 77 percent for the whole country) with 83.4 percent Catholic (including 83.2 percent Roman Catholic); 4.7 percent Protestant Christian (including 1.2 percent Anglican, 0.7 percent United Church; and 0.5 percent Baptist); 1.4 percent Orthodox Christian (including 0.7 percent Greek Orthodox); and 0.8 percent other Christian; as well as 1.5 percent Muslim; 1.3 percent Jewish; 0.6 percent Buddhist; 0.3 percent Hindu; and 0.1 percent Sikh. An additional 5.8 percent of the population said they had no religious affiliation (including 5.6 percent who stated that they had no religion at all).

Percentages are calculated as a proportion of the total number of respondents (7,125,580)[138]

Language

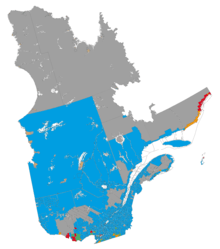

Linguistic map of the province of Quebec (source: Statistics Canada, 2006 census):

Francophone majority, less than 33% Anglophone

Francophone majority, more than 33% Anglophone

Anglophone majority, less than 33% Francophone

Anglophone majority, more than 33% Francophone

Allophone majority (indigenous)

Data not available

|

The official language of Quebec is French. Quebec is the only Canadian province whose population is mainly Francophone; 6,102,210 people (78.1 percent of the population) recorded it as their sole native language in the 2011 Census, and 6,249,085 (80.0%) recorded that they spoke it most often at home.[139] Knowledge of French is widespread even among those who do not speak it natively; in 2011, about 94.4 percent of the total population reported being able to speak French, alone or in combination with other languages, while 47.3% reported being able to speak English.[139]

In 2011, 599,230 people (7.7 percent of the population) people in Quebec declared English to be their mother tongue, and 767,415 (9.8 percent) used it most often as their home language[139] The English-speaking community or Anglophones are entitled to services in English in the areas of justice, health, and education;[140] services in English are offered in municipalities in which more than half the residents have English as their mother tongue. Allophones, people whose mother tongue is neither French nor English, made up 12.3 percent (961,700) of the population, according to the 2011 census, though a smaller figure – 554,400 (7.1 percent) – actually used these languages most often in the home.[139]

A considerable number of Quebec residents consider themselves to be bilingual in French and English. In Quebec, about 42.6 percent of the population (3,328,725 people) report knowing both languages; this is the highest proportion of bilinguals of any Canadian province.[139] One specific area in the Bilingual Belt called the West Island of Montreal, represented by the federal electoral district of Lac-Saint-Louis, is the most bilingual area in the province: 72.8% of its residents claim to know English and French according to the most recent census.[141] In contrast, in the rest of Canada, in 2006 only about 10.2 percent (2,430,990) of the population had a knowledge of both of the country's official languages. Altogether, 17.5% of Canadians are bilingual in French and English.[139]

In 2011, the most common mother tongue languages in the province were as follows: (Figures shown are for single-language responses only.)

| Language | Number of native speakers |

Percentage of singular responses |

|---|---|---|

| French | 6,102,210 | 78% |

| English | 599,230 | 7.7% |

| Arabic | 164,390 | 2% |

| Spanish | 141,000 | 1.8% |

| Italian | 121,720 | 1.6% |

Following were Creoles (0.8%), Chinese (0.6%), Greek (0.5%), Portuguese (0.5%), Romanian (0.4%), Vietnamese (0.3%), and Russian (0.3%). In addition, 152,820 (2.0%) reported having more than one native language.[139]

English is not designated an official language by Quebec law.[140] However, both English and French are required by the Constitution Act, 1867, for the enactment of laws and regulations, and any person may use English or French in the National Assembly and the courts. The books and records of the National Assembly must also be kept in both languages.[142][143] Until 1969, Quebec was the only officially bilingual province in Canada and most public institutions functioned in both languages. English was also used in the legislature, government commissions and courts.

Since the 1970s, languages other than French on commercial signs have been permitted only if French is given marked prominence. This law has been the subject of periodic controversy since its inception. The written forms of French place-names in Canada retain their diacritics such as accent marks over vowels in English text. Legitimate exceptions are Montreal and Quebec. However, the accented forms are increasingly evident in some publications. The Canadian Style states that Montréal and Québec (the city) must retain their accents in English federal documents.

Population centres

Economy

Quebec has an advanced, market-based, and open economy. In 2009, its gross domestic product (GDP) of US$32,408 per capita at purchasing power parity puts the province at par with Japan, Italy and Spain, but remains lower than the Canadian average of US$37,830 per capita.[145] The economy of Quebec is ranked the 37th largest economy in the world just behind Greece and 28th for the gross domestic product (GDP) per capita.[146][147]

The economy of Quebec represents 20.36% of the total GDP of Canada. Like most industrialized countries, the economy of Quebec is based mainly on the services sector. Quebec's economy has traditionally been fuelled by abundant natural resources, a well-developed infrastructure, and average productivity. The provincial GDP in 2010 was C$319,348 billion,[148] which makes Quebec the second largest economy in Canada.

The provincial debt-to-GDP ratio peaked at 50.7% in fiscal year 2012–2013, and is projected to decline to 33.8% in 2023–2024.[149] The credit rating of Quebec is currently Aa2 according to the Moody's agency.[150] In June 2017 S&P rated Quebec as an AA- credit risk, surpassing Ontario for the first time.[151]

Quebec's economy has undergone tremendous changes over the last decade.[152] Firmly grounded in the knowledge economy, Quebec has one of the highest growth rate of gross domestic product (GDP) in Canada. The knowledge sector represents about 30.9% of Quebec's GDP.[153] Quebec is experiencing faster growth of its R&D spending than other Canadian provinces.[154] Quebec's spending in R&D in 2011 was equal to 2.63% of GDP, above the European Union average of 1.84% and will have to reaches the target of devoting 3% of GDP to research and development activities in 2013 according to the Lisbon Strategy.[155] The percentage spent on research and technology (R&D) is the highest in Canada and higher than the averages for the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and the G7 countries.[156] Approximately 1.1 million Quebecers work in the field of science and technology.[157]

Quebec is also a major player in several leading-edge industries including aerospace, information technologies and software and multimedia. Approximately 60% of the production of the Canadian aerospace industry are from Quebec, where sales totalled C$12.4 billion in 2009.[161] Quebec is one of North America's leading high-tech player. This vast sector encompassing approximately 7,300 businesses and employ more than 145,000 people.[162] Pauline Marois has recently unveiled a two billion dollar budget for the period between 2013 to 2017 to create about 115,000 new jobs in knowledge and innovation sectors. The government promises to provide about 3% of Quebec's GDP in research and development (R&D).[163]

About 180 000 Quebeckers work in different field of information technology.[164] Approximately 52% of Canadian companies in these sectors are based in Quebec, mainly in Montreal and Quebec City. There are currently approximately 115 telecommunications companies established in the province, such as Motorola and Ericsson. About 60 000 people currently working in computer software development. Approximately 12 900 people working in over 110 companies such as IBM, CMC, and Matrox. The multimedia sector is also dominated by the province of Quebec. Several companies, such as Ubisoft settled in Quebec since the late 1990s.[165]

The mining industry accounted for 6.3% of Quebec's GDP.[166] It employs about 50,000 people[167] in 158 companies.[167]

The pulp and paper industries generate annual shipments valued at more than $14 billion.[168] The forest products industry ranks second in exports, with shipments valued at almost $11 billion. It is also the main, and in some circumstances only, source of manufacturing activity in more than 250 municipalities in the province. The forest industry has slowed in recent years because of the softwood lumber dispute.[169] This industry employs 68,000 people in several regions of Quebec.[170] This industry accounted for 3.1% of Quebec's GDP.[171]

Agri-food industry plays an important role in the economy of Quebec, with meat and Dairy products being the two main sectors. It accounts for 8% of the Quebec's GDP and generate $19.2 billion. This industry generated 487,000 jobs in agriculture, fisheries, manufacturing of food, beverages and tobacco and food distribution.[172]

Natural resources

The abundance of natural resources gives Quebec an advantageous position on the world market. Quebec stands out particularly in the mining sector, ranking among the top ten areas to do business in mining.[173] It also stands for the exploitation of its forest resources.

Quebec is remarkable for the natural resources of its vast territory. It has about 30 mines, 158 exploration companies and fifteen primary processing industries. Many metallic minerals are exploited, the principals are gold, iron, copper and zinc. Many other substances are extracted including titanium, asbestos, silver, magnesium, nickel and many other metals and industrial minerals.[174] However, only 40% of the mineral potential of Quebec is currently known. In 2003, the value of mineral exploitation reached Quebec 3.7 billion Canadian dollars.[175] Moreover, as a major centre of exploration for diamonds,[176] Quebec has seen, since 2002, an increase in its mineral explorations, particularly in the Northwest as well as in the Otish Mountains and the Torngat Mountains.

The vast majority (90.5%) of Quebec's forests are publicly owned. Forests cover more than half of Quebec's territory, for a total area of nearly 761,100 square kilometres (293,900 sq mi).[177] The Quebec forest area covers seven degrees of latitude.

More than a million lakes and rivers cover Quebec, occupying 21% of the total area of its territory. The aquatic environment is composed of 12.1% of fresh water and 9.2% of saltwater (percentage of total QC area).[178]

Science and technology

The government of Quebec has launched the Stratégie québécoise de la recherche et de l'innovation (SQRI) in 2007 which aims to promote development through research, science and technology. The government hopes to create a strong culture of innovation in Quebec for the next decades and to create a sustainable economy.[179] The spending on research and development reached some 7.824 billion dollars in 2007, roughly the equivalent of 2.63% of Quebec's GDP.[179] Quebec is ranked, as of March 2011, 13th in the world in terms of investment in research and development.[180] The research and development expenditures will be more than 3% of the province's GDP in 2013. The R&D expenditure in Quebec is higher than the average G7 and OECD countries.[157] Science and technology are key factors in the economic position of Quebec. More than one million people in Quebec are employed in the science and technology sector.[157]

Quebec is considered as one of world leaders in fundamental scientific research, having produced ten Nobel laureates in either physics, chemistry, or medicine.[182] It is also considered as one of the world leaders in sectors such as aerospace, information technology, biotechnology and pharmaceuticals, and therefore plays a significant role in the world's scientific and technological communities.[183] Quebec is also active in the development of its energy industries, including renewable energy such as hydropower and wind power. Quebec has had over 9,469 scientific publications in the sector of medicine, biomedical research and engineering since the year 2000.[184] Overall, the province of Quebec count about 125 scientific publications per 100,000 inhabitants in 2009.[185] The contribution of Quebec in science and technology represent approximately 1% of the researches worldwide since the 1980s to 2009.[186] Between 1991 to 2000, Quebec produced more scientific papers per 100,000 inhabitants than the United States and Germany.[187]

The Canadian Space Agency was established in Quebec due to its major role in this research field. A total of three Quebecers have been in space since the creation of the CSA: Marc Garneau, Julie Payette and Guy Laliberté. Quebec has also contributed to the creation of some Canadian artificial satellites including SCISAT-1, ISIS, Radarsat-1 and Radarsat-2.[188][189][190]

The province is one of the world leaders in the field of space science and contributed to important discoveries in this field.[191] One of the most recent is the discovery of the complex extrasolar planets system HR 8799. HR 8799 is the first direct observation of an exoplanet in history.[192][193] Olivier Daigle and Claude Carignan, astrophysicists from Université de Montréal have invented an astronomical camera approximately 500 times more powerful than those currently on the market.[194] It is therefore considered as the most sensitive camera in the world.[195][196][197] The Mont Mégantic Observatory was recently equipped with this camera.[198]

Quebec ranks among the world leaders in the field of life science.[199] William Osler, Wilder Penfield, Donald Hebb, Brenda Milner, and others made significant discoveries in medicine, neuroscience and psychology while working at McGill University in Montreal. Quebec has more than 450 biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies which together employ more than 25,000 people and 10,000 highly qualified researchers.[199] Montreal is ranked 4th in North America for the number of jobs in the pharmaceutical sector.[199][200]

Infrastructure

Transportation

Development and security of land transportation in Canada are provided by the ministère des Transports du Québec.[201] Other organizations, such as the Canadian Coast Guard and Nav Canada, provide the same service for the sea and air transportation. The Commission des transports du Québec works with the freight carriers and the public transport.

The réseau routier québécois (Quebec road network) is managed by the Société de l'assurance automobile du Québec (SAAQ) (Quebec Automobile Insurance Corporation) and consists of about 185,000 kilometres (115,000 mi) of highways and national, regional, local, collector and forest roads. In addition, Quebec has almost 12,000 bridges, tunnels, retaining walls, culverts and other structures[202] such as the Quebec Bridge, the Laviolette Bridge and the Louis-Hippolyte Lafontaine Bridge–Tunnel.

In the waters of the St. Lawrence there are eight deep-water ports for the transhipment of goods. In 2003, 3886 cargo and 9.7 million tonnes of goods transited the Quebec portion of the St. Lawrence Seaway.[203]

Concerning rail transport, Quebec has 6,678 kilometres (4,150 mi) of railways[204] integrated in the large North American network. Although primarily intended for the transport of goods through companies such as the Canadian National (CN) and the Canadian Pacific (CP), the Quebec railway network is also used by inter-city passengers via Via Rail Canada and Amtrak. In April 2012, plans were unveiled for the construction of an 800 km (497 mi) railway running north from Sept-Îles, to support mining and other resource extraction in the Labrador Trough.[205]

The upper air network includes 43 airports that offer scheduled services on a daily basis.[203] In addition, the Government of Quebec owns airports and heliports to increase the accessibility of local services to communities in the Basse-Côte-Nord and northern regions.[206]

Various other transport networks crisscross the province of Quebec, including hiking trails, snowmobile trails and bike paths; the Green Road being the largest with nearly 4,000 kilometres (2,500 mi) in length.[207]

Energy

Quebec has been described as a potential clean energy superpower.[208][209] The energy balance of Quebec has undergone a large shift over the past 30 years. In 2008, electricity ranked as the main form of energy used in Quebec (41.6%), followed by oil (38.2%) and natural gas (10.7%).[210]

Quebec is the fourth largest producer of hydroelectricity in the world after China, Brazil and the United States and relies almost exclusively (96% in 2008) on this source of renewable energy for its electricity needs.[211]

Culture

Quebec is at the centre of French-speaking culture in North America. Its culture is a symbol of a distinct perspective. Quebec nationalism has been one expression of this perspective. Quebec's culture blends its historic roots with its aboriginal heritage and the contributions of recent immigrants, as well as receiving a strong influence from English-speaking North America.

Montreal's cabarets rose to the forefront of the city's cultural life during the Prohibition era of Canada and the United States in the 1920s. The cabarets radically transformed the artistic scene, greatly influencing the live entertainment industry of Quebec.[212] The Quartier Latin (English: Latin Quarter) of Montreal, and Vieux-Québec (English: Old Quebec) in Quebec City, are two hubs of activity for today's artists. Life in the cafés and "terrasses" (outdoor restaurant terraces) reveals a Latin influence in Quebec's culture, with the théâtre Saint-Denis in Montréal and the Capitole de Québec theatre in Quebec City being among the principal attractions.

A number of governmental and non-government organizations support cultural activity in Quebec. The Conseil des arts et des lettres du Québec (CALQ) is an initiative of the Ministry of Culture and Communications (Quebec). It supports creation, innovation, production, and international exhibits for all cultural fields of Quebec. The Société de développement des entreprises culturelles (SODEC) works to promote and fund individuals working in the cultural industry. The Prix du Québec is an award given by the government to confer the highest distinction and honour to individuals demonstrating exceptional achievement in their respective cultural field.

Society

On February 8, 2007, Quebec Premier Jean Charest announced the setting up of a Commission tasked with consulting Quebec Society on the matter of arrangements regarding cultural diversity. The Premier's press release[213] reasserted the three fundamental values of Quebec society:

Equality between men and women, primacy of the French language, and separation of church and state constitute the fundamental values. They are not subject to any arrangement. They cannot be subordinated by any other principle.[213]

Furthermore, Quebec is a free and democratic society that abides by the rule of law.[214] Quebec society bases its cohesion and specificity on a set of statements, a few notable examples of which include:

- The Quebec Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms[215]

- The Charter of the French Language[216]

- The Civil Code of Quebec[217]

Music and dance

Traditional music is imbued with many dances, such as the jig, the quadrille, the reel and line dancing, which developed in the festivities since the early days of colonization. Various instruments are more popular in Quebec's culture: harmonica (music-of-mouth or lip-destruction), fiddle, spoons, jaw harp and accordion. The podorythmie is a characteristic of traditional Quebec music and means giving the rhythm with the feet.[218] Quebec traditional music is currently provided by various contemporary groups seen mostly during Christmas and New Year's Eve celebrations, Quebec National Holiday and many local festivals.

Being a modern cosmopolitan society, today, all types of music can be found in Quebec. From folk music to hip-hop, music has always played an important role in Quebercers culture. From La Bolduc in the 1920s–1930s to the contemporary artists, the music in Quebec has announced multiple songwriters and performers, pop singers and crooners, music groups and many more. Quebec's most popular artists of the last century include the singers Félix Leclerc (1950s), Gilles Vigneault (1960s–present), Kate and Anna McGarrigle (1970s–present) and Céline Dion (1980s–present).[219] The First Nations and the Inuit of Quebec also have their own traditional music.

From Quebec's musical repertoire, the song A La Claire Fontaine[220] was the anthem of the New France, Patriots and French Canadian, then replaced by O Canada. Currently, the song Gens du pays is by far preferred by many Quebecers to be the national anthem of Quebec. The Association québécoise de l'industrie du disque, du spectacle et de la vidéo (ADISQ) was created in 1978 to promote the music industry in Quebec.[221] The Orchestre symphonique de Québec and the Orchestre symphonique de Montréal are respectively associated with the Opéra de Québec and the Opéra de Montreal whose performances are presented at the Grand Théâtre de Québec and at Place des Arts. The Ballets Jazz de Montreal, the Grands Ballets and La La La Human Steps are three important professional troupes of contemporary dance.

Film, television, and radio

The Cinémathèque québécoise has a mandate to promote the film and television heritage of Quebec. Similarly, the National Film Board of Canada (NFB), a federal Crown corporation, provides for the same mission in Canada. In a similar way, the Association of Film and Television in Quebec (APFTQ) promotes independent production in film and television.[222] While the Association of Producers and Directors of Quebec (APDQ) represents the business of filmmaking and television, the Association of Community Radio Broadcasters of Quebec (ARCQ) (French acronym) represents the independent radio stations.[223] Several movie theatres across Quebec ensure the dissemination of Quebec cinema. With its cinematic installations, such as the Cité du cinéma and Mel's studios, the city of Montreal is home to the filming of various productions.[224] The State corporation Télé-Québec, the federal Crown corporation CBC, general and specialized private channels, networks, independent and community radio stations broadcast the various Quebec téléromans, the national and regional news, interactive and spoken programmations, etc.[225][226] Les Rendez-vous du cinéma québécois is a festival surrounding the ceremony of the Jutra Awards Night that rewards work and personalities of Quebec cinema.[227] The Artis and the Gemini Awards gala recognize the personalities of television and radio industry in Quebec and French Canada. The Film Festival of the 3 Americas, Quebec City, the Festival of International Short Film, Saguenay, the World Film Festival and the Festival of New Cinema, Montreal, are other annual events surrounding the film industry in Quebec.

Literature and theatre

From New France, Quebec literature was first developed in the travel accounts of explorers such as Jacques Cartier, Jean de Brébeuf, the Baron de La Hontan and Nicolas Perrot, describing their relations with indigenous peoples. The Moulin à paroles traces the great texts that have shaped the history of Quebec since its foundation in 1534 until the era of modernity. The first to write the history of Quebec, since its discovery, was the historian François-Xavier Garneau. This author will be part of the current of patriotic literature (also known as the "poets of the country" and literary identity) that will arise after the Patriots Rebellion of 1837–1838.[228]

Various tales and stories are told through oral tradition, such as, among many more, the legends of the Bogeyman, the Chasse-galerie, the Black Horse of Trois-Pistoles, the Complainte de Cadieux, the Corriveau, the dancing devil of Saint-Ambroise, the Giant Beaupré, the monsters of the lakes Pohénégamook and Memphremagog, of Quebec Bridge (called the Devil's Bridge), the Rocher Percé and of Rose Latulipe, for example.[229]

Many Quebec poets and prominent authors marked their era and today remain anchored in the collective imagination, like, among others, Philippe Aubert de Gaspé, Octave Crémazie, Honoré Beaugrand, Émile Nelligan, Lionel Groulx, Gabrielle Roy, Hubert Aquin, Michel Tremblay, Marie Laberge, Fred Pellerin and Gaston Miron. The regional novel from Quebec is called Terroir novel and is a literary tradition[230] specific to the province. It includes such works as The Old Canadians, Maria Chapdelaine, Un homme et son péché, Le Survenant, etc. There are also many successful plays from this literary category, such as Les Belles-sœurs and Broue (Brew).

Among the theatre troupes are the Compagnie Jean-Duceppe, the Théâtre La Rubrique at the Pierrette-Gaudreault venue of the Institut of arts in Saguenay, the Théâtre Le Grenier, etc. In addition to the network of cultural centres in Quebec,[231] the venues include the Monument-National and the Rideau Vert (green curtain) Theatre in Montreal, the Trident Theatre in Quebec City, etc. The National Theatre School of Canada and the Conservatoire de musique et d'art dramatique du Québec form the future players.

Popular French-language contemporary writers include Louis Caron, Suzanne Jacob, Yves Beauchemin, and Gilles Archambault. Mavis Gallant, born in Quebec, lived in Paris from the 1950s onward. Well-known English-language writers from Quebec include Leonard Cohen, Mordecai Richler, and Neil Bissoondath.

- Émile Nelligan, a Quebec poet famous for his poem Winter evening

Fine arts

First influenced since the days of New France by Catholicism, with works from Frère Luc (Brother Luke) and more recently from Ozias Leduc and Guido Nincheri, art of Quebec has developed around the specific characteristics of its landscapes and cultural, historical, social and political representations.[232]

Thus, the development of Quebec masterpieces in painting, printmaking and sculpture is marked by the contribution of artists such as Louis-Philippe Hébert, Cornelius Krieghoff, Alfred Laliberté, Marc-Aurèle Fortin, Marc-Aurèle de Foy Suzor-Coté, Jean Paul Lemieux, Clarence Gagnon, Adrien Dufresne, Alfred Pellan, Jean-Philippe Dallaire, Charles Daudelin, Arthur Villeneuve, Jean-Paul Riopelle, Paul-Émile Borduas and Marcelle Ferron.

The Fine arts of Quebec are displayed at the Quebec National Museum of Fine Arts, the Montreal Museum of Contemporary Art, the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, the Quebec Salon des métiers d'art and in many art galleries. While many works decorate the public areas of Quebec, others are displayed in foreign countries such as the sculpture Embâcle (Jam) by Charles Daudelin on Québec Place in Paris and the statue Québec Libre! (free Quebec!) by Armand Vaillancourt in San Francisco. The Montreal School of Fine Arts forms the painters, printmakers and sculptors of Quebec.

Various buildings reflect the architectural heritage that characterizes Quebec, such as religious buildings, city halls, houses of large estates, and other locations throughout the province.

Circus and street art

Several circus troupes were created in recent decades, the most important being without any doubt the Cirque du Soleil.[233] Among these troops are contemporary, travelling and on-horseback circuses, such as Les 7 Doigts de la Main, Cirque Éloize, Cavalia, Kosmogonia, Saka and Cirque Akya.[234] Presented outdoors under a tent or in venues similar to the Montreal Casino, the circuses attract large crowds both in Quebec and abroad. In the manner of touring companies of the Renaissance, the clowns, street performers, minstrels, or troubadours travel from city to city to play their comedies. Although they may appear randomly from time to time during the year, they are always visible in the cultural events such as the Winterlude in Gatineau, the Quebec Winter Carnival, the Gatineau Hot Air Balloon Festival, the Quebec City Summer Festival, the Just for Laughs Festival in Montreal and the Festival of New France in Quebec.

The National Circus School and the École de cirque de Québec were created to train future Contemporary circus artists. For its part, Tohu, la Cité des Arts du Cirque was founded in 2004 to disseminate the circus arts.[235]

Heritage

The Cultural Heritage Fund is a program of the Quebec government[236] for the conservation and development of Quebec's heritage, together with various laws.[237] Several organizations ensure that same mission, both in the social and cultural traditions in the countryside and heritage buildings, including the Commission des biens culturels du Québec, the Quebec Heritage Fondation, the Conservation Centre of Quebec, the Centre for development of living heritage, the Quebec Council of living heri tage, the Quebec Association of heritage interpretation, etc.