Governor General of Canada

The governor general of Canada (French: la gouverneure générale du Canada)[n 1] is the federal viceregal representative of the Canadian monarch, currently Queen Elizabeth II. The Queen, as a political sovereign, is shared equally both with the 15 other Commonwealth realms and the 10 provinces of Canada, but she physically resides predominantly in her oldest and most populous realm, the United Kingdom. The Queen, on the advice of her Canadian prime minister,[1] appoints a governor general to carry out most of her constitutional and ceremonial duties. The commission is for an unfixed period of time—known as serving at Her Majesty's pleasure—though five years is the normal convention. Beginning in 1959, it has also been traditional to rotate between anglophone and francophone officeholders—although many recent governors general have been bilingual. Once in office, the governor general maintains direct contact with the Queen, wherever she may be at the time.[2]

| Governor General of Canada

Gouverneure générale du Canada | |

|---|---|

Viceregal badge | |

| |

| Viceroy | |

| Style | Her Excellency, The Right Honourable |

| Residence | Rideau Hall, Ottawa; La Citadelle, Quebec City |

| Appointer | Monarch of Canada on the advice of the Prime Minister of Canada |

| Term length | At Her Majesty's pleasure |

| Formation | 1 July 1867 |

| First holder | The Viscount Monck |

| Salary | CA$288,900 annually |

| Website | www |

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Canada |

| Government (structure) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Related topics

|

|

|

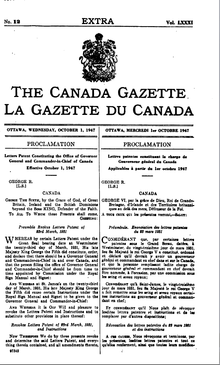

The office began in the 16th and 17th centuries with the Crown-appointed governors of the French colony of Canada followed by the British governors of Canada in the 18th and 19th centuries. Subsequently, the office is, along with the Crown, the oldest continuous institution in Canada.[3] The present incarnation of the office emerged with Canadian Confederation and the passing of the British North America Act, 1867, which defines the role of the governor general as "carrying on the Government of Canada on behalf and in the Name of the Queen, by whatever Title he is designated".[4] Although the post initially still represented the government of the United Kingdom (that is, the monarch in her British council), the office was gradually Canadianized until, with the passage of the Statute of Westminster in 1931 and the establishment of a separate and uniquely Canadian monarchy, the governor general became the direct personal representative of the independently and uniquely Canadian sovereign, the monarch in his Canadian council.[5][6][7][8] Throughout this process of gradually increasing Canadian independence, the role of governor general took on additional responsibilities. For example, in 1904, the Militia Act granted permission for the governor general to use the title of Commander-in-Chief of the Canadian militia,[9] while Command-in-Chief remained vested in the sovereign,[10] and in 1927 the first official international visit by a governor general was made.[11][12] Finally, in 1947, King George VI issued letters patent allowing the viceroy to carry out almost all of the monarch's powers on his or her behalf. As a result, the day-to-day duties of the monarch are carried out by the governor general, although, as a matter of law, the governor general is not in the same constitutional position as the sovereign;[13] the office itself does not independently possess any powers of the Royal Prerogative. In accordance with the Constitution Act, 1982, any constitutional amendment that affects the Crown, including the office of the Governor General, requires the unanimous consent of each provincial legislature as well as the federal parliament.

The current governor general is Julie Payette, who has served since 2 October 2017; Prime Minister Justin Trudeau recommended her to succeed David Johnston.[14][15]

Spelling of title

The letters patent constituting the office, and official publications of the Government of Canada, spell the title governor general, without a hyphen.[16][17] As governor is the noun in the title, it is pluralized thus, governors general, rather than governor generals. Moreover, both terms are capitalized when used in the formal title preceding an incumbent's name.

Appointment

The position of governor general is mandated by both the Constitution Act, 1867 (formerly known as the British North America Act, 1867) and the letters patent issued in 1947 by King George VI.[16] As such, on the recommendation of his or her Canadian prime minister, the Canadian monarch appoints the governor general by commission issued under the royal sign-manual and Great Seal of Canada. That individual is, from then until being sworn-in, referred to as the governor general-designate.[16][18][19][20][21][22]

Besides the administration of the oaths of office, there is no set formula for the swearing-in of a governor general-designate.[20] Though there may therefore be variations to the following, the appointee will generally travel to Ottawa, there receiving an official welcome and taking up residence at 7 Rideau Gate,[20][23] and will begin preparations for their upcoming role, meeting with various high level officials to ensure a smooth transition between governors general. The sovereign will also hold an audience with the appointee and will at that time induct both the governor general-designate and his or her spouse into the Order of Canada as Companions, as well as appointing the former as a Commander of both the Order of Military Merit and the Order of Merit of the Police Forces (should either person not have already received either of those honours).[20]

The incumbent will generally serve for at least five years, though this is only a developed convention, and the governor general acts at Her Majesty's pleasure (or the Royal Pleasure).[24] The prime minister may therefore recommend to the Queen that the viceroy remain in her service for a longer period of time, sometimes upwards of more than seven years.[n 2] A governor general may also resign,[n 3] and two have died in office.[n 4] In such a circumstance, or if the governor general leaves the country for longer than one month, the chief justice of Canada (or, if that position is vacant or unavailable, the senior puisne justice of the Supreme Court) serves as administrator of the government and exercises all powers of the governor general.[n 5]

Selection

In a speech on the subject of confederation, made in 1866 to the Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada, John A. Macdonald said of the planned governor: "We place no restriction on Her Majesty's prerogative in the selection of her representative ... The sovereign has unrestricted freedom of choice ... We leave that to Her Majesty in all confidence."[25] However, between 1867 and 1931, governors general were appointed by the monarch on the advice of the British Cabinet. Thereafter, in accordance with the Statute of Westminster 1931, the appointment was made by the sovereign with the direction of his or her Canadian ministers only. Until 1952, all governors general were also either members of the Peerage or sons of peers, and were born beyond Canada's borders. These viceroys spent a relatively limited time in Canada, but their travel schedules were so extensive that they could "learn more about Canada in five years than many Canadians in a lifetime".[26] Still, though all Canadian nationals were as equally British subjects as their British counterparts prior to the implementation of the Canadian Citizenship Act in 1947, the idea of Canadian-born persons being appointed governor general was raised as early as 1919, when, at the Paris Peace Conference, Canadian prime minister Robert Borden consulted with Prime Minister of South Africa Louis Botha and the two agreed that the viceregal appointees should be long-term residents of their respective Dominions.[27] Calls for just such an individual to be made viceroy came again in the late 1930s,[28] but it was not until Vincent Massey's appointment by King George VI in 1952 that the position was filled by a Canadian-born individual. Massey stated of this that "a Canadian [as governor general] makes it far easier to look on the Crown as our own and on the Sovereign as Queen of Canada."[29] This practice continued until 1999, when Queen Elizabeth II commissioned as her representative Adrienne Clarkson, a Hong Kong-born refugee to Canada. Moreover, the practice of alternating between anglophone and francophone Canadians was instituted with the appointment of Georges Vanier, a francophone who succeeded the anglophone Massey. All persons whose names are put forward to the Queen for approval must first undergo background checks by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and the Canadian Security Intelligence Service.[30][31]

Although required by the tenets of constitutional monarchy to be nonpartisan while in office, governors general were frequently former politicians; a number held seats in the British House of Lords by virtue of their inclusion in the peerage. Appointments of former ministers of the Crown in the 1980s and 1990s were criticized by Peter H. Russell, who stated in 2009: "much of [the] advantage of the monarchical system is lost in Canada when prime ministers recommend partisan colleagues to be appointed governor general and represent [the Queen]."[32] Clarkson was the first governor general in Canadian history without either a political or military background, as well as the first Asian-Canadian and the second woman, following on Jeanne Sauvé. The third woman to hold this position was also the first Caribbean-Canadian governor general, Michaëlle Jean.

There have been, from time to time, proposals put forward for modifications to the selection process of the governor general. Most recently, the group Citizens for a Canadian Republic has advocated the election of the nominee to the Queen, either by popular or parliamentary vote;[33] a proposal echoed by Adrienne Clarkson, who called for the prime minister's choice to not only be vetted by a parliamentary committee,[34][35] but also submit to a televised quiz on Canadiana.[36] Constitutional scholars, editorial boards, and the Monarchist League of Canada have argued against any such constitutional tinkering with the viceregal appointment process, stating that the position being "not elected is an asset, not a handicap", and that an election would politicize the office, thereby undermining the impartiality necessary to the proper functioning of the governor general.[37][38]

A new approach was used in 2010 for the selection of David Johnston as governor general-designate. For the task, Prime Minister Stephen Harper convened a special search group—the Governor General Consultation Committee[39]—was instructed to find a non-partisan candidate who would respect the monarchical aspects of the viceregal office and conducted extensive consultations with more than 200 people across the country.[40][41][42][43] In 2012, the committee was made permanent and renamed as the Advisory Committee on Vice-Regal Appointments, with a modified membership and its scope broadened to include the appointment of provincial lieutenant governors and territorial commissioners (though the latter are not personal representatives of the monarch).[44] However, Justin Trudeau did not make use of a selection committee when he recommended Julie Payette as Johnston's successor in 2017.[45]

Swearing-in ceremony

| External video | |

|---|---|

The swearing-in ceremony begins with the arrival at 7 Rideau Gate of one of the ministers of the Crown, who then accompanies the governor general-designate to Parliament Hill, where a Canadian Forces Guard of Honour (consisting of the Army Guard, Royal Canadian Air Force Guard, and Flag Party of the Royal Canadian Navy) awaits to give a general salute. From there, the party is led by the Queen's parliamentary messenger—the Usher of the Black Rod—to the Senate chamber, wherein all justices of the Supreme Court, senators, members of parliament, and other guests are assembled. The Queen's commission for the governor general-designate is then read aloud by the Secretary to the Governor General and the required oaths are administered to the appointee by either the chief justice or one of the puisne justices of the Supreme Court; the three oaths are: the Oath of Allegiance, the Oath of Office as Governor General and Commander-in-Chief, and the Oath as Keeper of the Great Seal of Canada. With the affixing of their signature to these three solemn promises, the individual is officially the governor general, and at that moment the Flag of the Governor General of Canada is raised on the Peace Tower,[20] the Viceregal Salute is played by the Central Band of the Canadian Forces, and a 21-gun salute is conducted by the Royal Regiment of Canadian Artillery. The governor general is seated on the throne while a prayer is read, and then receives the Great Seal of Canada (which is passed to the registrar general for protection),[46] as well as the chains of both the Chancellor of the Order of Canada and of the Order of Military Merit.[47] The governor general will then give a speech, outlining whichever cause or causes they will champion during their time as viceroy.[20]

Role

Governor General the Marquess of Aberdeen, 1893

Canada shares the person of the sovereign equally with 15 other countries in the Commonwealth of Nations and that individual, in his or her capacity as the Canadian sovereign, has 10 other legal personas within the Canadian federation. As the sovereign works and resides predominantly outside of Canada's borders, the governor general's primary task is to perform the monarch's federal constitutional duties on his or her behalf.[49][50] As such, the governor general carries "on the Government of Canada on behalf and in the name of the Sovereign".[51]

The governor general acts within the principles of parliamentary democracy and responsible government as a guarantor of continuous and stable governance and as a nonpartisan safeguard against the abuse of power.[52][53][54] For the most part, however, the powers of the Crown are exercised on a day-to-day basis by elected and appointed individuals, leaving the governor general to perform the various ceremonial duties the sovereign otherwise carries out when in the country; at such a moment, the governor general removes him or herself from public,[n 6] though the presence of the monarch does not affect the governor general's ability to perform governmental roles.[56][57]

Past governor general the Marquess of Lorne said of the job: "It is no easy thing to be a governor general of Canada. You must have the patience of a saint, the smile of a cherub, the generosity of an Indian prince, and the back of a camel",[58] and the Earl of Dufferin stated that the governor general is "A representative of all that is august, stable, and sedate in the government, the history, and the traditions of the country; incapable of partizanship, and lifted far above the atmosphere of faction; without adherents to reward or opponents to oust from office; docile to the suggestions of his Ministers, and yet securing to the people the certainty of being able to get rid of an Administration or Parliament the moment either had forfeited their confidence."[59]

Constitutional role

Though the monarch retains all executive, legislative, and judicial power in and over Canada,[60][61] the governor general is permitted to exercise most of this, including the Royal Prerogative, in the sovereign's name; some as outlined in the Constitution Act, 1867, and some through various letters patent issued over the decades, particularly those from 1947 that constitute the Office of Governor General of Canada;[62] they state: "And We do hereby authorize and empower Our Governor General, with the advice of Our Privy Council for Canada or of any members thereof or individually, as the case requires, to exercise all powers and authorities lawfully belonging to Us in respect of Canada."[63] The office itself does not, however, independently possess any powers of the Royal Prerogative, only exercising the Crown's powers with its permission; a fact the Constitution Act, 1867 left unchanged.[64] Among other duties, the monarch retains the sole right to appoint the governor general.[7] It is also stipulated that the governor general may appoint deputies—usually Supreme Court justices and the Secretary to the Governor General—who can perform some of the viceroy's constitutional duties in his or her stead,[65] and the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court (or a puisne justice in the chief justice's absence) will act as the administrator of the government upon the death or removal, as well as the incapacitation, or absence of the governor general for more than one month.[66]

It is the governor general who is required by the Constitution Act, 1867, to appoint for life persons to the Queen's Privy Council for Canada,[67] who are all theoretically tasked with tendering to the monarch and viceroy guidance on the exercise of the Royal Prerogative. Convention dictates, though, that the governor general must draw from the privy council an individual to act as prime minister—in almost all cases the Member of Parliament who commands the confidence of the House of Commons. The prime minister then advises the governor general to appoint other members of parliament to a committee of the privy council known as the Cabinet, and it is in practice only from this group of ministers of the Crown that the Queen and governor general will take advice on the use of executive power;[68] an arrangement called the Queen-in-Council or,[61] more specifically, the Governor-in-Council. In this capacity, the governor general will issue royal proclamations and sign orders in council. The Governor-in-Council is also specifically tasked by the Constitution Act, 1867, to appoint in the Queen's name the lieutenant governors of the provinces (with the Advisory Committee on Vice-Regal Appointments and the premiers of the provinces concerned playing an advisory role),[69] senators,[70] the speaker of the Senate,[71] supreme court justices,[72] and superior and county court judges in each province, except those of the Courts of Probate in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick.[73] The advice given by the Cabinet is, in order to ensure the stability of government, by political convention typically binding; both the Queen and her viceroy, however, may in exceptional circumstances invoke the reserve powers, which remain the Crown's final check against a ministry's abuse of power.[n 7][74]

The governor general, as the representative of the Canadian sovereign, carries out the parliamentary duties of the sovereign in their absence, such as summoning parliament, reading the speech from the throne, and proroguing and dissolving parliament. The governor general also grants Royal Assent in the Queen's name; legally, he or she has three options: grant Royal Assent (making the bill a law), withhold Royal Assent (vetoing the bill), or reserve the bill for the signification of the Queen's pleasure (allowing the sovereign to personally grant or withhold assent).[75] If the governor general withholds the Queen's assent, the sovereign may within two years disallow the bill, thereby annulling the law in question. No modern Canadian viceroy has denied Royal Assent to a bill. Provincial viceroys, however, are able to reserve Royal Assent to provincial bills for the governor general, which was last invoked in 1961 by the lieutenant governor of Saskatchewan.[76]

Ceremonial role

With most constitutional functions lent to Cabinet, the governor general acts in a primarily ceremonial fashion. He or she will host members of Canada's royal family, as well as foreign royalty and heads of state, and will represent the Queen and country abroad on state visits to other nations,[77][74] though the monarch's permission is necessary, via the prime minister, for the viceroy to leave Canada.[78] Also as part of international relations, the governor general issues letters of credence and of recall for Canadian ambassadors and receives the same from foreign ambassadors appointed to Canada.

The governor general is also tasked with fostering national unity and pride.[79] Queen Elizabeth II stated in 1959 to then Governor General Vincent Massey "maintain[ing] the right relationship between the Crown and the people of Canada [is] the most important function among the many duties of the appointment which you have held with such distinction."[80] One way in which this is carried out is travelling the country and meeting with Canadians from all regions and ethnic groups in Canada,[77] continuing the tradition begun in 1869 by Governor General the Lord Lisgar.[81] He or she will also induct individuals into the various national orders and present national medals and decorations. Similarly, the viceroy administers and distributes the Governor General's Awards, and will also give out awards associated with private organizations, some of which are named for past governors general.[77] During a federal election, the governor general will curtail these public duties, so as not to appear as though they are involving themselves in political affairs.

Although the constitution of Canada states that the "Command-in-Chief of the Land and Naval Militia, and of all Naval and Military Forces, of and in Canada, is hereby declared to continue and be vested in the Queen,"[10] the governor general acts in her place as Commander-in-Chief of the Canadian Forces and is permitted through the 1947 Letters Patent to use the title Commander-in-Chief in and over Canada.[9][16] The position technically involves issuing commands for Canadian troops, airmen, and sailors, but is predominantly a ceremonial role in which the viceroy will visit Canadian Forces bases across Canada and abroad to take part in military ceremonies, see troops off to and return from active duty, and encourage excellence and morale amongst the forces.[9] The governor general also serves as honorary Colonel of three household regiments: the Governor General's Horse Guards, Governor General's Foot Guards and Canadian Grenadier Guards. This ceremonial position is directly under that of Colonel-in-Chief, which is held by the Queen. Since 1910, the governor general was also always made the Chief Scout for Canada, which was renamed Chief Scout of Canada after 1946 and again in 2011 as Patron Scout.[82]

Residences and household

.jpg)

Rideau Hall, located in Ottawa, is the official residence of the Canadian monarch[83] and of the governor general and is thus the location of the viceregal household and the Chancellery of Honours. For a part of each year since 1872, governors general have also resided at the Citadel (La Citadelle) in Quebec City, Quebec.[84] A governor general's wife is known as the chatelaine of Rideau Hall, though there is no equivalent term for a governor general's husband.

The viceregal household aids the governor general in the execution of the royal constitutional and ceremonial duties and is managed by the Office of the Secretary to the Governor General.[85] The Chancellery of Honours centres around the Queen and is thus also located at Rideau Hall and administered by the governor general. As such, the viceroy's secretary ex officio holds the position of Herald Chancellor of Canada,[86] overseeing the Canadian Heraldic Authority—the mechanism of the Canadian honours system by which armorial bearings are granted to Canadians by the governor general in the name of the sovereign.[86] These organized offices and support systems include aides-de-camp, press officers, financial managers,[85] speech writers, trip organizers, event planners, protocol officers, chefs and other kitchen employees, waiters, and various cleaning staff, as well as visitors' centre staff and tour guides at both official residences. In this official and bureaucratic capacity, the entire household is often referred to as Government House[87] and its departments are funded through the normal federal budgetary process,[88] as is the governor general's salary of CAD$288,900,[89] which has been taxed since 2013.[90][91] Additional costs are incurred from separate ministries and organizations such as the National Capital Commission, the Department of National Defence, and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.[92]

The governor general's air transportation is assigned to 412 Transport Squadron of the Royal Canadian Air Force. The squadron uses Bombardier Challenger 600 VIP jets to transport the governor general to locations within and outside of Canada.

Symbols and protocol

As the personal representative of the monarch, the governor general follows only the sovereign in the Canadian order of precedence, preceding even other members of the Royal Family. Though the federal viceroy is considered primus inter pares amongst his or her provincial counterparts, the governor general also outranks the lieutenant governors in the federal sphere; at provincial functions, however, the relevant lieutenant governor, as the Queen's representative in the province, precedes the governor general.[93] The incumbent governor general and his or her spouse are also the only people in Canada, other than serving Canadian ambassadors and high commissioners, entitled to the use of the style His or Her Excellency and the governor general is granted the additional honorific of The Right Honourable for their time in office and for life afterwards.[94][95][96]

Prior to 1952, all Governors General of Canada were members of the peerage. Typically, individuals appointed as federal viceroy were already a peer, either by inheriting the title, such as the Duke of Devonshire, or by prior elevation by the sovereign in their own right, as was the case with the Viscount Alexander of Tunis. None were life peers, the Life Peerages Act 1958 postdating the beginning of the tradition of appointing Canadian citizens as governor general. John Buchan was, in preparation for his appointment as governor general, made the Baron Tweedsmuir of Elsfield in the County of Oxford by King George V, six months before Buchan was sworn in as viceroy. The Leader of His Majesty's Loyal Opposition at the time, William Lyon Mackenzie King, felt Buchan should serve as governor general as a commoner;[97] however, George V insisted he be represented by a peer. With the appointment of Vincent Massey as governor general in 1952, governors general ceased to be members of the peerage; successive governments since that date have held to the non-binding and defeated (in 1934) principles of the 1919 Nickle Resolution.

Under the orders' constitutions, the governor general serves as the Chancellor and Principal Companion of the Order of Canada,[98] the Chancellor of the Order of Military Merit,[99] and the Chancellor of the Order of Merit of the Police Forces.[100] He or she also upon installation automatically becomes a Knight or Dame of Justice and the Prior and Chief Officer in Canada of the Most Venerable Order of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem.[101] As acting commander-in-chief, the governor general is further routinely granted the Canadian Forces Decoration by the Chief of the Defence Staff on behalf of the monarch. All of these honours are retained following an incumbent's departure from office, with the individual remaining in the highest categories of the orders, and they may also be further distinguished with induction into other orders or the receipt of other awards.[n 8]

The Viceregal Salute—composed of the first six bars of the Royal Anthem ("God Save the Queen") followed by the first and last four bars of the national anthem ("O Canada")—is the salute used to greet the governor general upon arrival at, and mark his or her departure from most official events.[103] To mark the viceroy's presence at any building, ship, airplane, or car in Canada, the governor general's flag is employed. The present form was adopted on 23 February 1981 and,[104] in the federal jurisdiction, takes precedence over all other flags except for the Queen's personal Canadian standard.[105] When the governor general undertakes a state visit, however, the national flag is generally employed to mark his or her presence.[104] This flag is also, along with all flags on Canadian Forces property, flown at half-mast upon the death of an incumbent or former governor general.[106]

The crest of the Royal Arms of Canada is employed as the badge of the governor general, appearing on the viceroy's flag and on other objects associated with the person or the office. This is the fourth such incarnation of the governor general's mark since confederation.[107]

|

.svg.png) |

|

|

|

| 1901 | 1921 | 1931 | 1953 | 1981 |

History

French and British colonies

French colonization of North America began in the 1580s and Aymar de Chaste was appointed in 1602 by King Henry IV as Viceroy of Canada.[108][109] The explorer Samuel de Champlain became the first unofficial Governor of New France in the early 17th century,[n 9] serving until Charles Huault de Montmagny was in 1636 formally appointed to the post by King Louis XIII. The French Company of One Hundred Associates then administered New France until King Louis XIV took control of the colony and appointed Augustin de Saffray de Mésy as the first governor general in 1663,[111] after whom 12 more people served in the post.

With the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1763, France relinquished most of its North American territories, including Canada, to Great Britain.[112] King George III then issued in that same year a royal proclamation establishing, amongst other regulations, the Office of the Governor of Quebec to preside over the new Province of Quebec.[113] Nova Scotia and New Brunswick remained completely separate colonies, each with their own governor, until the cabinet of William Pitt adopted in the 1780s the idea that they, along with Quebec and Prince Edward Island, should have as their respective governors a single individual styled as Governor-in-Chief. The post was created in 1786, with The Lord Dorchester as its first occupant. However, the governor-in-chief directly governed only Quebec. It was not until the splitting in 1791 of the Province of Quebec, to accommodate the influx of United Empire Loyalists fleeing the American revolutionary war, that the king's representative, with a change in title to Governor General, directly governed Lower Canada, while the other three colonies were each administered by a lieutenant governor in his stead.

Responsible government

The Rebellions of 1837 brought about great changes to the role of the governor general, prompting, as they did, the British government to grant responsible government to the Canadian provinces.[114][115] As a result, the viceroys became largely nominal heads, while the democratically elected legislatures and the premiers they supported exercised the authority belonging to the Crown; a concept first put to the test when, in 1849, Governor-General of the Province of Canada and Lieutenant-Governor of Canada East the Earl of Elgin granted Royal Assent to the Rebellion Losses Bill, despite his personal misgivings towards the legislation.[116]

This arrangement continued after the reunification in 1840 of Upper and Lower Canada into the Province of Canada, and the establishment of the Dominion of Canada in 1867. The governor general carried out in Canada all the parliamentary and ceremonial functions of a constitutional monarch—amongst other things, granting Royal Assent, issuing Orders-in-Council, and taking advice from the Canadian privy council. However, the governor still remained not a viceroy, in the true sense of the word, being still a representative of and liaison to the British government[57][117]—the Queen in her British council of ministers—who answered to the secretary of state for the colonies in London and who,[118] as a British observer of Canadian politics, held well into the First World War a suite of offices in the East Block of Parliament Hill.[n 10] But, the new position of Canadian high commissioner to the United Kingdom, created in 1880, began to take over the governor general's role as a link between the Canadian and British governments, leaving the viceroy increasingly as a personal representative of the monarch.[119] As such, the governor general had to retain a sense of political neutrality; a skill that was put to the test when the Marquess of Lorne disagreed with his Canadian prime minister, John A. Macdonald, over the dismissal of Lieutenant Governor of Quebec Luc Letellier de St-Just. On the advice of the colonial secretary, and to avoid conflict with the cabinet of Canada, the Marquess did eventually concede, and released St-Just from duty.[120] The governor general was then in May 1891 called upon to resolve the Dominion's first cabinet crisis, wherein Prime Minister Macdonald died, leaving the Lord Stanley of Preston to select a new prime minister.

As early as 1880, the viceregal family and court attracted minor ridicule from the Queen's subjects: in July of that year, someone under the pseudonym Captain Mac included in a pamphlet called Canada: from the Lakes to the Gulf, a coarse satire of an investiture ceremony at Rideau Hall, in which a retired inn-keeper and his wife undergo the rigorous protocol of the royal household and sprawl on the floor before the Duke of Argyll so as to be granted the knighthood for which they had "paid in cold, hard cash".[121] Later, prior to the arrival of Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught and Strathearn (the uncle of King George V), to take up the post of governor general, there was a "feeble undercurrent of criticism" centring on worries about a rigid court at Rideau Hall; worries that turned out to be unfounded as the royal couple was actually more relaxed than their predecessors.[122]

Emerging nationality to an independent kingdom

During the First World War, into which Canada was drawn due to its association with the United Kingdom, the governor general's role turned from one of cultural patron and state ceremony to one of military inspector and morale booster. Starting in 1914, Governor General Prince Arthur donned his Field Marshal's uniform and put his efforts into raising contingents, inspecting army camps, and seeing troops off before their voyage to Europe. These actions, however, led to conflict with the prime minister at the time, Robert Borden; though the latter placed blame on the Military Secretary Edward Stanton, he also opined that the Duke "laboured under the handicap of his position as a member of the Royal Family and never realized his limitations as Governor General".[123] Prince Arthur's successor, the Duke of Devonshire, faced the Conscription Crisis of 1917 and held discussions with his Canadian prime minister, as well as members of His Majesty's Loyal Opposition, on the matter. Once the government implemented conscription, Devonshire, after consulting on the pulse of the nation with Sir Wilfrid Laurier, Vincent Massey, Henri Bourassa, Archbishop of Montreal Paul Bruchési, Duncan Campbell Scott, Vilhjalmur Stefansson, and Stephen Leacock, made efforts to conciliate Quebec, though he had little real success.[124]

Canada's national sentiment had gained fortitude through the country's sacrifices on the battlefields of the First World War and, by war's end, the interference of the British government in Canadian affairs was causing ever-increasing discontent amongst Canadian officials;[n 11] in 1918, the Toronto Star was even advocating the end of the office.[126] The governor general's role was also changing to focus less on the larger Empire and more on uniquely Canadian affairs,[n 12] including the undertaking of official international visits on behalf of Canada, the first being that of the Marquess of Willingdon to the United States, where he was accorded by President Calvin Coolidge the full honours of representative of a head of state.[n 13][11] It would be another decade, however, before the King-Byng Affair: another catalyst for change in the relationship between Canada—indeed, all the Dominions—and the United Kingdom, and thus the purpose of the governor general.

In 1926, Liberal Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King, facing a non-confidence vote in the House of Commons over a scandal in his party, requested that Governor General Lord Byng dissolve parliament and call an election. Byng, however, refused his Canadian prime minister's advice, citing both the facts that King held the minority of seats in the house and that a general election had been held only months earlier; he thus called on Arthur Meighen to form a government. Within a week however, Meighen's Conservative government lost its own non-confidence vote, forcing the Governor General to dissolve parliament and call elections that saw Mackenzie King returned to power.[128] King then went on to the Imperial Conference that same year and there pushed for reorganizations that resulted in the Balfour Declaration, which declared formally the practical reality that had existed for some years: namely, that the Dominions were fully autonomous and equal in status to the United Kingdom.[129] These new developments were codified in the Statute of Westminster, through the enactment of which on 11 December 1931, Canada, along with the Union of South Africa and the Irish Free State, immediately obtained formal legislative independence from the UK.[130] In addition, the Balfour Declaration also held that the governor general would cease to act as the representative of the British government. Accordingly, in 1928, the United Kingdom appointed its first High Commissioner to Canada thus effectively ending the governor general's diplomatic role as the British government's envoy.[131]

The governor general thus became solely the representative of the King within Canadian jurisdiction, ceasing completely to be an agent of the British Cabinet,[n 14][8][133] and as such would be appointed by the monarch granting his royal sign-manual under the Great Seal of Canada only on the advice of his Canadian prime minister.[134]

The Canadian Cabinet's first recommendation under this new system was still, however, a British subject born outside of Canada: Lord Tweedsmuir. His birthplace aside, though, the professional author took further than any of his predecessors the idea of a distinct Canadian identity,[135] travelling the length and breadth of the country, including, for the first time for a governor general, the Arctic regions.[136] Not all Canadians, however, shared Tweedsmuir's views; the Baron raised the ire of imperialists when he said in Montreal in 1937: "a Canadian's first loyalty is not to the British Commonwealth of Nations, but to Canada and Canada's King",[137] a statement the Montreal Gazette dubbed as "disloyal".[138] During Tweedsmuir's time as viceroy, which started in 1935, calls began to emerge for a Canadian-born individual to be appointed as governor general; but Tweedsmuir died suddenly in office in 1940, while Canada was in the midst of the Second World War, and Prime Minister Mackenzie King did not feel it was the right time to search for a suitable Canadian.[139] The Earl of Athlone was instead appointed by King George VI, Athlone's nephew, to be his viceroy for the duration of the war.

Quebec nationalism and constitutional patriation

It was in 1952, a mere five days before King George VI's death, that Vincent Massey became the first Canadian-born person to be appointed as a governor general in Canada since the Marquis de Vaudreuil-Cavagnal was made Governor General of New France on 1 January 1755, as well as the first not to be elevated to the peerage since Sir Edmund Walker Head in 1854. There was some trepidation about this departure from tradition and Massey was intended to be a compromise: he was known to embody loyalty, dignity, and formality, as expected from a viceroy.[140] As his viceregal tenure neared an end, it was thought that Massey, an anglophone, should be followed by a francophone Canadian; and so, in spite of his Liberal Party attachments, Georges Vanier was chosen by Conservative Prime Minister John Diefenbaker as the next governor general. Vanier was subsequently appointed by Queen Elizabeth II in person at a meeting of her Canadian Cabinet,[141] thus initiating the convention of alternating between individuals from Canada's two main linguistic groups. This move did not, however, placate those who were fostering the new Quebec nationalist movement, for whom the monarchy and other federal institutions were a target for attack. Though Vanier was a native of Quebec and fostered biculturalism, he was not immune to the barbs of the province's sovereigntists and, when he attended la Fête St-Jean-Baptiste in Montreal in 1964, a group of separatists held placards reading "Vanier vendu" ("Vanier sold out") and "Vanier fou de la Reine" ("Vanier Queen's jester").[142]

In light of this regional nationalism and a resultant change in attitudes towards Canadian identity, images and the role of the monarchy were cautiously downplayed, and Vanier's successor, Roland Michener, was the last viceroy to practice many of the office's ancient traditions, such as the wearing of the Windsor uniform, the requirement of court dress for state occasions, and expecting women to curtsey before the governor general.[143] At the same time, he initiated new practices for the viceroy, including regular conferences with the lieutenant governors and the undertaking of state visits.[143] He presided over Canada's centennial celebrations and the coincidental Expo 67, to which French president Charles de Gaulle was invited. Michener was with de Gaulle when he made his infamous "Vive le Québec libre" speech in Montreal and was cheered wildly by the gathered crowd while they booed and jeered Michener.[144] With the additional recognition of the monarchy as a Canadian institution,[145][146] the establishment of a distinct Canadian honours system, an increase of state visits coming with Canada's growing role on the world stage, and the more prevalent use of television to visually broadcast ceremonial state affairs, the governor general became more publicly active in national life.

The Cabinet in June 1978 put forward the constitutional amendment Bill C-60, that, amongst other changes, vested executive authority directly in the governor general and renamed the position as First Canadian,[147][148][149] but the proposal was thwarted by the provincial premiers.[150][151][152] When the constitution was patriated four years later, the new amending formula for the documents outlined that any changes to the Crown, including the Office of the Governor General, would require the consent of all the provincial legislatures plus the federal parliament.[153] By 1984, Canada's first female governor general—Jeanne Sauvé—was appointed. While it was she who created the Canadian Heraldic Authority, as permitted by letters patent from Queen Elizabeth II, and who championed youth and world peace, Sauvé proved to be a controversial vicereine, closing to the public the grounds of the Queen's residence and self-aggrandizingly breaching protocol on a number of occasions.[149][154][155]

Withering and renaissance

Sarah, Duchess of York, said in 2009 that sometime during her marriage to Prince Andrew, Duke of York, her husband was offered the position of governor general of Canada, and she speculated in hindsight that their agreement to refuse the commission may have been a contributing factor in their eventual break-up.[156] Instead, Sauvé's tenure as governor general was book-ended by a series of appointments—Edward Schreyer, Ray Hnatyshyn, and Roméo LeBlanc—that have been generally regarded as mere patronage postings for former politicians and friends of the incumbent prime minister at the time,[n 15][79][149] and despite the duties they carried out, their combined time in the viceregal office is generally viewed as unremarkable at best, and damaging to the office at worst.[79][149][157][158][159] As David Smith described it: "Notwithstanding the personal qualities of the appointees, which have often been extraordinary, the Canadian governor general has become a hermetic head of state—ignored by press, politicians and public."[160] It was theorized by Peter Boyce that this was due, in part, to widespread misunderstanding about the governor general's role coupled with a lack of public presence compared to the media coverage dedicated to the increasingly presidentialized prime minister.[79]

It was with the Queen's appointment of Adrienne Clarkson, on the advice of then Prime Minister Jean Chrétien, that a shift in the office took place. Clarkson was the first Canadian viceroy to have not previously held any political or military position—coming as she did from a background of television journalism with the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation—was the first since 1952 to have been born outside of Canada, the first from a visible minority (she is of Chinese ancestry), and, by her being accompanied to Rideau Hall by her husband, author and philosopher John Ralston Saul, the official appointment brought an unofficial pair to the viceregal placement,[161][162] in that the governor general would not be the only person actively exploring Canadian theory and culture. Clarkson managed to bring the viceregal office back into the collective consciousness of Canadians, winning praise for touring the country more than any of her predecessors, her inspiring speeches, and her dedication to the military in her role as the Commander-in-Chief's representative.[163][164][165][166][167][168] This did not come without a cost, however, as the attention also drew widespread criticism of the governor general's increased spending on state affairs, for which the office was symbolically rebuked by parliament when it voted in favour of cutting by 10% the viceregal budget it had earlier supported,[169][170] as well as for fostering the notion, through various demonstrations, that the governor general was ultimately the Canadian head of state above the Queen herself,[171][172][173] an approach that was said by Jack Granatstein to have caused "a fury" with the Queen on one occasion in 2004.[174] This attitude was not unique to Clarkson, though; it had been observed that, for some decades, staff at Rideau Hall and various government departments in Ottawa had been pushing to present the governor general as head of state,[175] part of a wider Liberal policy on the monarchy that had been in effect at least since the proposed constitutional changes in the 1970s,[149] if not the 1964 Truncheon Saturday riot in Quebec City.[173] Indeed, international observers opined that the viceroys had been, over the years, making deliberate attempts to distance themselves from the sovereign, for fear of being too closely associated with any "Britishness" the monarch embodied.[79]

Prime Minister Paul Martin followed Chrétien's example and, for Clarkson's successor, put forward to the Queen the name of Michaëlle Jean, who was, like Clarkson, a woman, a refugee, a member of a visible minority, a CBC career journalist, and married to an intellectual husband who worked in the arts.[176] Her appointment initially sparked accusations that she was a supporter of Quebec sovereignty, and it was observed that she had on a few occasions trodden into political matters,[177][178][179] as well as continuing to foster the notion that the governor general had replaced the Queen as head of state, thereby "unbalancing ... the federalist symmetry".[180] But Jean ultimately won plaudits,[159] particularly for her solidarity with the Canadian Forces and the Indigenous peoples in Canada, as well as her role in the parliamentary dispute that took place between December 2008 and January 2009.[181][182][183]

With the appointment of academic David Johnston, former principal of McGill University and subsequently president of the University of Waterloo, there was a signalled emphasis for the governor general to vigorously promote learning and innovation. Johnston stated in his inaugural address: "[We want to be] a society that innovates, embraces its talent and uses the knowledge of each of its citizens to improve the human condition for all."[184] There was also a recognition of Johnston's expertise in constitutional law, following the controversial prorogations of parliament in 2008 and 2009, which initiated some debate about the governor general's role as the representative of Canada's head of state.[185]

Activities post-commission

Retired governors general usually either withdraw from public life or go on to hold other public offices. Edward Schreyer, for instance, was appointed Canadian high commissioner to Australia upon his departure from the viceregal role in 1984, and Michaëlle Jean became the UNESCO special envoy to Haiti and, later, the secretary-general of La Francophonie.[186] Schreyer also become the first former governor general to run for elected office in Canada when he unsuccessfully vied for a seat in the House of Commons as a New Democratic Party candidate. Prior to 1952, several former viceroys returned to political careers in the United Kingdom, sitting with party affiliations in the House of Lords and, in some cases, taking a position in the British Cabinet.[n 16] The Marquess of Lorne was elected a Member of Parliament in the United Kingdom in 1895, and remained so until he became the Duke of Argyll and took his seat in the House of Lords. Others were made governors in other countries or territories: the Viscount Monck was appointed Lord Lieutenant of Dublin, the Earl of Aberdeen was appointed Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, and the Earl of Dufferin, the Marquess of Lansdowne, The Earl of Minto, and The Earl of Willingdon all subsequently served as Viceroy of India.

An outgoing governor general may leave an eponymous award as a legacy, such as the Stanley Cup, the Clarkson Cup, the Vanier Cup, or the Grey Cup. They may found an institution, as Georges Vanier did with the Vanier Institute of the Family and Adrienne Clarkson with the Institute for Canadian Citizenship. Three former governors general have released memoirs: the Lord Tweedsmuir (Memory Hold-the-Door), Vincent Massey (On Being Canadian and What's Past is Prologue), and Adrienne Clarkson (Heart Matters).

| Institution | Founded by |

|---|---|

| Royal Society of Canada | The Marquess of Lorne |

| Canada's first anti-tuberculosis association | The Earl of Minto |

| The Battlefields Park | The Lord Grey |

| King's Jubilee Cancer Fund | The Earl of Bessborough |

| Vanier Institute of the Family | Georges Vanier[187] |

| Sauvé Foundation | Jeanne Sauvé |

| Governor General Ramon John Hnatyshyn Education Fund | Ray Hnatyshyn[188] |

| International Council for Canadian Studies | Ray Hnatyshyn[188] |

| The Hnatyshyn Foundation | Ray Hnatyshyn[189] |

| Institute for Canadian Citizenship | Adrienne Clarkson |

| Michaëlle Jean Foundation | Michaëlle Jean |

See also

Notes

- When the position is held by a male, the French title is Gouverneur général du Canada.

- Georges Vanier acted as governor general between 15 September 1959 and 5 March 1967, and Roland Michener served for just under seven years, from 17 April 1967 to 14 January 1974.

- Roméo LeBlanc resigned the viceregal post in 1999 due to health concerns.

- The Lord Tweedsmuir died at the Montreal Neurological Institute and Hospital on 11 February 1940, and Georges Vanier died at Rideau Hall on 5 March 1967.

- The only individuals to serve as administrators due to the deaths of governors general were Chief Justice Sir Lyman Poore Duff in 1940 and Chief Justice Robert Taschereau in 1967.

- Governor General the Lord Tweedsmuir said of King George VI being in the Senate in 1939 to grant Royal Assent to bills: "[When the King of Canada is present] I cease to exist as Viceroy, and retain only a shadowy legal existence as Governor General in Council."[55]

- See Note 1 at Queen's Privy Council for Canada.

- Some seven years after he left office, the Earl Alexander of Tunis was appointed as a Member of the Order of Merit. Similarly, Vincent Massey was awarded the Royal Victorian Chain by Queen Elizabeth II approximately six months after leaving the viceregal post and was in 1967 invested into the Order of Canada.[102] Roland Michener was presented with the Royal Victorian Chain a few months before he retired as governor general.

- Kevin MacLeod, in his book A Crown of Maples, pegs the start date of Champlain's governorship at 1627,[3] whereas the official website of the Governor General of Canada puts it at 1608.[110]

- The offices were subsequently incorporated into the Prime Minister's Office (PMO), but have been restored to their 19th century appearance after the PMO moved to the Langevin Block in the 1970s, and are now preserved as a tourist attraction along with other historic offices in the East Block.[6]

- The appointment in 1916 of the Duke of Devonshire as governor general caused political problems, as Canadian prime minister Robert Borden had, counter to established common practice, not been consulted on the matter by his British counterpart, H. H. Asquith.[125]

- During the Great Depression, the Earl of Bessborough voluntarily cut his salary by ten percent as a sign of his solidarity with the Canadian people.[127]

- Governors general had been venturing to Washington to meet informally with the President of the United States since the time of the Viscount Monck.

- The ministers in attendance at the Imperial Conference agreed that: "In our opinion it is an essential consequence of the equality of status existing among the members of the British Commonwealth of Nations that the Governor General of a Dominion is the representative of the Crown, holding in all essential respects the same position in relation to the administration of public affairs in the Dominion as is held by His Majesty the King in great Britain, and that he is not the representative or agent of His Majesty's Government in Great Britain or of any Department of that Government."[132]

- LeBlanc's strong ties to the Liberal Party led other party leaders to protest his appointment by boycotting his installation ceremony.[157]

- In 1952, the Earl Alexander of Tunis resigned as Governor General of Canada to accept an appointment as Minister of Defence in the Cabinet of Winston Churchill. The Marquess of Lansdowne and the Duke of Devonshire both also served in the British Cabinet following their viceregal careers, and Lansdowne went on to serve as leader of the Conservative Party in the House of Lords for over a decade.

References

- The Royal Household. "The Queen and the Commonwealth > Queen and Canada > The Queen's role in Canada". Queen's Printer. Retrieved 2 June 2009.

- The Royal Household. "Queen and Canada: The role of the Governor-General". Queen's Printer. Retrieved 28 May 2009.

- MacLeod, Kevin S. (2008). A Crown of Maples (PDF) (1 ed.). Ottawa: Queen's Printer for Canada. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-662-46012-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2009.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Victoria (1867), Constitution Act, 1867, III.10, Westminster: Queen's Printer (published 29 March 1867), retrieved 15 January 2009CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- MacLeod 2008, pp. 34–35

- Public Works and Government Services Canada. "Parliament Hill > The History of Parliament Hill > East Block > Office of the Governor General". Queen's Printer for Canada. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

- MacLeod 2008, p. 35

- Department of Canadian Heritage (2008). Canada: Symbols of Canada. Ottawa: Queen's Printer for Canada. p. 3. Archived from the original on 17 February 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Office of the Governor General of Canada. "Commander in Chief". Queen's Printer for Canada. Archived from the original on 9 October 2006. Retrieved 5 November 2007.

- Victoria 1867, III.15

- Hubbard, R.H. (1977). Rideau Hall. Montreal and London: McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-7735-0310-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Office of the Governor General of Canada. "Governor General > Former Governors General > The Marquess of Willingdon". Queen's Printer for Canada. Retrieved 28 May 2009.

- Walters, Mark D. (2011). "The Law behind the Conventions of the Constitution: Reassessing the Prorogation Debate" (PDF). Journal of Parliamentary and Political Law. 5: 131–154. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- "Prime Minister Trudeau announces The Queen's approval of Canada's next Governor General". pm.gc.ca. Government of Canada. 13 July 2017.

- http://www.macleans.ca/news/julie-payette-named-governor-general/

- George VI (1947), Letters Patent Constituting the Office of Governor General of Canada, I, Ottawa: King's Printer for Canada (published 1 October 1947), retrieved 29 May 2009CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Governor General". gg.ca. Office of the Secretary to the Governor General. 20 December 2016.

- Elizabeth II (28 September 1999), Royal Commission, Queen's Printer for Canada, archived from the original on 13 August 2011, retrieved 13 July 2010

- Elizabeth II (10 September 2005), Royal Commission, Queen's Printer for Canada, archived from the original on 13 August 2011, retrieved 13 July 2010

- Department of Canadian Heritage. "Monarchy in Canada > Governor General Designate". Queen's Printer for Canada. Archived from the original on 14 July 2010. Retrieved 13 July 2010.

- "Gov. Gen. designate denies separatist link". CTV. 18 August 2005. Archived from the original on 11 February 2006. Retrieved 29 May 2009.

- "Haitian community holds special church service for the governor general-designate". CBC. 27 August 2005. Archived from the original on 3 December 2010. Retrieved 29 May 2009.

- Fidelis (2005). "The Installation of the Governor General in 2005: Innovation and Evolution?" (PDF). Canadian Monarchist News. Toronto: Monarchist League of Canada. Fall-Winter 2005 (24): 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2009. Retrieved 29 May 2009.

- "Part I > Proclamation" (PDF). Canada Gazette. Extra 139 (8). 27 September 2005. p. 1. Retrieved 2 June 2009.

- Copeland, Lewis; Lamm, Lawrence W.; McKenna, Stephen J. (1999). The World's Great Speeches. Mineola: Courier Dover Publications. p. 381. ISBN 978-0-486-40903-0.

- Hubbard 1977, p. 145

- Hubbard 1977, p. 147

- Office of the Governor General of Canada. "Governor General > Former Governors General > Major General The Earl of Athlone". Queen's Printer for Canada. Retrieved 29 May 2009.

- Trepanier, Peter (2006), "A Not Unwilling Subject: Canada and Her Queen", in Coates, Colin M. (ed.), Majesty in Canada, Hamilton: Dundurn Press, p. 143, ISBN 978-1-55002-586-6, retrieved 16 October 2012

- LeBlanc, Daniel (13 August 2005). "Martin defends viceregal couple's loyalty". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. Archived from the original on 15 August 2005. Retrieved 22 February 2009.

- "New governor general must clarify sovereignty position, premiers say". CBC. 12 August 2005. Archived from the original on 4 February 2007. Retrieved 12 August 2005.

- Russell, Peter H. (2009), Joyal, Serge (ed.), "Diminishing the Crown", The Globe and Mail, Toronto (published 10 June 2010), retrieved 13 August 2010

- "Our Goals > A Solution". Citizens for a Canadian Republic. Retrieved 7 June 2009.

- Valpy, Michael (17 April 2009). "Let MPs vet G-G candidates, and show hearings, Clarkson says". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. Archived from the original on 20 April 2009. Retrieved 23 April 2009.

- Ferguson, Rob (17 April 2009). "Crisis showed Parliamentary system not understood: Clarkson". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on 12 September 2012. Retrieved 7 June 2009.

- Canwest News Service (18 April 2009). "Clarkson backs test". Windsor Star. Retrieved 23 April 2009.

- "One thing in Ottawa that doesn't need fixing". The Gazette. 23 April 2009. Retrieved 23 April 2009.

- McCreery, Christopher (22 July 2005), "Christopher McCreery", The Globe and Mail, Toronto, retrieved 10 May 2012

- Canada News Centre. "Governor General Consultation Committee". Queen's Printer for Canada. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 6 August 2010.

- Curry, Bill (11 July 2010), "Selection panel ordered to find non-partisan governor-general: PMO", The Globe and Mail, archived from the original on 16 July 2010, retrieved 11 July 2010

- Ditchburn, Jennifer (28 June 2010), "Tight circle of monarchists helping Harper pick next Governor General", Winnipeg Free Press, archived from the original on 8 July 2010, retrieved 10 July 2010

- "David Johnston: a worthy viceroy", The Globe and Mail, Toronto, 9 July 2010, retrieved 9 July 2010

- Office of the Prime Minister of Canada (8 July 2010). "PM welcomes appointment of David Johnston as Governor General Designate". Queen's Printer for Canada. Archived from the original on 12 July 2010. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- Cheadle, Bruce (4 November 2012), Harper creates new panel to ensure 'non-partisan' vice regal appointments, The Canadian Press, archived from the original on 7 February 2013, retrieved 4 November 2012

- Press, Jordan (20 July 2017), Julie Payette's vetting for governor general questioned amid 'disquieting' revelations, The Canadian Press, retrieved 20 July 2017

- Office of the Governor General of Canada. "Media > Fact Sheets > The Great Seal of Canada". Queen's Printer for Canada. Retrieved 30 May 2009.

- "Adrienne Clarkson Installed as Governor General". Canadian Monarchist News. Toronto: Monarchist League of Canada. Autumn 1999 (3). 1999. Archived from the original on 8 July 2009. Retrieved 29 May 2009.

- Hamilton-Gordon, John (1960). Hamilton-Gordon, Ishbel (ed.). "We Twa". The Canadian journal of Lady Aberdeen, 1893–1898. 2. Montreal: Champlain Society (published 17 September 1893). pp. 13–15.

- Government of Canada (2 October 2014). "The Governor General". Her Queen's Printer for Canada. Archived from the original on 14 November 2015. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- Government of Canada (24 September 2014). "The Crown". Queen's Printer for Canada. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- Elizabeth II (1985). "Interpretations Act, 1985". Ottawwa: Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- Roberts, Edward (2009). "Ensuring Constitutional Wisdom During Unconventional Times" (PDF). Canadian Parliamentary Review. Ottawa: Commonwealth Parliamentary Association. 23 (1): 15. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 February 2010. Retrieved 21 May 2009.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Office of the Governor General of Canada. "Governor General > Role and Responsibilities > A Modern Governor General – Active and Engaged". Queen's Printer for Canada. Retrieved 30 May 2009.

- MacLeod 2008, pp. 16, 20

- Galbraith, William (1989). "Fiftieth Anniversary of the 1939 Royal Visit" (PDF). Canadian Parliamentary Review. Ottawa: Commonwealth Parliamentary Association. 12 (3): 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 March 2011. Retrieved 22 February 2009.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Department of National Defence (1 April 1999). The Honours, Flags and Heritage Structure of the Canadian Forces (PDF). Ottawa: Queen's Printer for Canada. p. 1A-3. A-AD-200-000/AG-000. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2009. Retrieved 23 May 2009.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Heard, Andrew (1990), Canadian Independence, Vancouver: Simon Fraser University, retrieved 25 August 2010

- Campbell, John (c. 1880). Written at Ottawa. MacNutt, W. Stewart (ed.). Days of Lorne: Impressions of a Governor-General. Fredericton: Brunswick Press (published 1955). p. 201.

- Hamilton-Temple-Blackwood, Frederick (12 January 1877). "Speech". In Hamilton-Temple-Blackwood, Frederick (ed.). Visit of his Excellency the Governor-General to the National Club. Toronto: Hunter Rose & Co. (published 1877). p. 10.

- Victoria 1867, III.9, IV.17

- MacLeod 2008, p. 17

- Library and Archives Canada. "Politics and Government > By Executive Decree > The Governor General". Queen's Printer for Canada. Archived from the original on 11 August 2009. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- George VI 1947, II

- Strong, Samuel Henry; Taschereau, Henri-Elzéar; Henry, William Alexander; Gwynne, John Wellington; Fournier, Télesphore (16 February 1885). "Windsor & Annapolis Railway Co. v. The Queen and the Western Counties Railway Co". Supreme Court of Canada. p. 389. Retrieved 25 September 2016.

- George VI 1947, VII

- George VI 1947, VIII

- Victoria 1867, III.11

- MacLeod 2008, pp. 24, 27

- Victoria 1867, V.58

- Victoria 1867, IV.24

- Victoria 1867, IV.34

- Elizabeth II (1985). Supreme Court Act. 4.2. Ottawa: Queen's Printer for Canada. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 31 May 2009.

- Victoria 1867, VII.96

- House of Commons. "The Governor General of Canada: Role, Duties and Funding for Activities". Queen's Printer for Canada. Archived from the original on 14 June 2012. Retrieved 9 October 2009.

- Victoria 1867, IV.55

- MacLeod 2008, p. 25

- Office of the Governor General of Canada. "Governor General > Role and Responsibilities". Queen's Printer for Canada. Retrieved 2 June 2009.

- George VI 1947, XIV

- Boyce, Peter (2008). Written at Sydney. Jackson, Michael D. (ed.). "The Senior Realms of the Queen > The Queen's Other Realms: The Crown and its Legacy in Australia, Canada and New Zealand" (PDF). Canadian Monarchist News. Autumn 2009 (30). Toronto: Monarchist League of Canada (published October 2009). p. 10. ISBN 978-1-86287-700-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 December 2009. Retrieved 22 October 2009.

- McCreery, Christopher (2008), On Her Majesty's Service: Royal Honours and Recognition in Canada, Toronto: Dundurn, p. 54, ISBN 978-1-4597-1224-9, retrieved 11 November 2015

- Hubbard 1977, p. 16

- "About > Management Team > Board of Governors". Scouts Canada. Archived from the original on 29 October 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

-

- MacLeod 2008, p. 34

- Galbraith 1989, p. 9

- Aimers, John (April 1996). "The Palace on the Rideau". Monarchy Canada. Toronto: Monarchist League of Canada (Spring 1996). Archived from the original on 31 January 2009. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- Lanctot, Gustave (1964). Royal Tour of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth in Canada and the United States of America 1939. Toronto: E.P. Taylor Foundation. ASIN B0006EB752.

- Toffoli, Gary (April 1995). "The Hnatyshyn Years". Monarchy Canada. Toronto: Monarchist League of Canada (Spring 1995). Archived from the original on 12 October 2006. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- Office of the Governor General of Canada. "La Citadelle > An Official Residence at the Heart of the Old Capital". Queen's Printer for Canada. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

- Office of the Governor General of Canada. "The Office > The Office of the Secretary to the Governor General". Queen's Printer for Canada. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

- Office of the Governor General of Canada. "Heraldry > The Canadian Heraldic Authority". Queen's Printer for Canada. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

- "Part I > Government House" (PDF). Canada Gazette. 143 (17). 25 April 2009. p. 1200. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

- Office of the Secretary to the Governor General (2007). Annual Report 2006–07 (PDF). Ottawa: Queen's Printer for Canada. p. 6. Appendix B.2.a. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 3 June 2009.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Parliament of Canada. "Salaries of the Governors General of Canada – 1869 To Date". Queen's Printer for Canada. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- Department of Finance Canada. "Budget 2012 – Annex 4". Queen's Printer for Canada. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- The Canadian Press (29 March 2012). "Governor General's salary to be taxed, but it won't cost him a dime". Winnipeg Free Press. Archived from the original on 1 April 2012. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- Office of the Secretary to the Governor General 2007, p. 3

- Department of Canadian Heritage. "Ceremonial and Canadian Symbols Promotion > Across Canada > Standards". Queen's Printer for Canada. Retrieved 19 June 2009.

- Department of National Defence 1999, pp. 11–2

- MacLeod 2008, p. 37

- Department of Canadian Heritage. "Table of titles to be used in Canada (as revised on June 18, 1993)". Queen's Printer for Canada. Retrieved 21 August 2009.

- Reynolds, Louise (2005). Mackenzie King: Friends & Lovers. Victoria: Trafford Publishing. p. 124. ISBN 978-1-4120-5985-5.

- Elizabeth II (28 October 2004). The Constitution of the Order of Canada. 3. Ottawa: Queen's Printer for Canada. Retrieved 2 June 2009.

- Elizabeth II (1997). "Constitution of the Order of Canada". In Department of National Defence (ed.). The Honours, Flags and Heritage Structure of the Canadian Forces (PDF). Ottawa: Queen's Printer for Canada (published 1 April 1999). pp. 2C1–1. A-AD-200-000/AG-000. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2009. Retrieved 2 June 2009.

- Office of the Governor General of Canada. "Honours > National Orders > Order of Merit of the Police Forces". Queen's Printer for Canada. Retrieved 2 June 2009.

- "Canada Wide > About Us > The Order of St. John > The Order of St. John in Canada". St. John Ambulance Canada. Retrieved 2 June 2009.

- "Library > Miscellaneous > Biographies > Vincent Massey". Answers Corporation. Retrieved 16 March 2009.

- Department of Canadian Heritage. "Ceremonial and Canadian Symbols Promotion > Honours and salutes > Musical salute". Queen's Printer for Canada. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

- Office of the Governor General of Canada. "Heraldry > Emblems of Canada and of Government House > Symbols of the Governor General > The Governor General's Flag". Queen's Printer for Canada. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

- Department of National Defence 1999, p. 14-2-2

- Department of National Defence 1999, p. 4-2-6

- Nelson, Phil. "Governor General of Canada (Canada)". Flags of the World. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- Hoxie, Frederick E. (September 1999). Encyclopedia of North American Indians. Darby: Diane Publishing Company. p. 284. ISBN 978-0-7881-6690-7.

- Tidridge, Nathan (2011). Canada's Constitutional Monarchy: An Introduction to Our Form of Government. Toronto: Dundurn Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-1-4597-0084-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Office of the Governor General of Canada. "Governor General > Role and Responsibilities > Role and Responsibilities of the Governor General". Queen's Printer for Canada. Retrieved 29 May 2009.

- Eccles, W.J. (1979) [1966]. "Saffray de Mézy (Mésy), Augustin de". In Brown, George Williams (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. I (1000–1700) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Emerich, John Edward; Acton, Dalberg; Benians, Ernest Alfred; Ward, Adolphus William; Prothero George Walter (29 October 1976). The Cambridge Modern History. 8. London: Cambridge University Press. pp. 346–347. ISBN 978-0-521-29108-8.

- George III (7 October 1763). The Royal Proclamation. Westminster: King's Printer. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- MacLeod 2008, p. 7

- Library and Archives Canada. "Politics and Government > By Executive Decree > The Executive Branch in Canadian History". Queen's Printer for Canada. Archived from the original on 30 June 2009. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- Mills, David (4 March 2015). "Rebellion Losses Bill". The Canadian Encyclopedia (online ed.). Historica Canada.

- Hilliker, John (1990). Canada's Department of External Affairs: The early years, 1909–1946. Montreal: McGill-Queen's Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-7735-0751-7.

- Library and Archives Canada. "Politics and Government > By Executive Decree > The Governor General". Queen's Printer for Canada. Archived from the original on 9 June 2009. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- Skelton, Oscar D. (2009), "The Day of Sir Wilfrid Laurier: A Chronicle of the 20th Century", in Wrong, George M.; Langton, H. H. (eds.), The Chronicles of Canada, III, Tucson: Fireship Press, p. 228, ISBN 978-1-934757-51-2, retrieved 1 July 2010

- MacNutt 1955, p. 47

- Hubbard 1977, pp. 55–56

- Hubbard 1977, p. 125

- Borden, Robert (1938). Borden, Henry (ed.). Memoirs. 1. New York: Macmillan Publishers. pp. 601–602.

- Hubbard 1977, pp. 141–142

- Office of the Governor General of Canada. "Former Governors General: The Duke of Devonshire". Queen's Printer for Canada. Retrieved 18 April 2009.

- Hubbard 1977, p. 42

- Cowan, John (1965). Canada's Governors General, Lord Monck to General Vanier (2 ed.). York: York Publishing Co. p. 156.

- Williams, Jeffery (1983). Byng of Vimy: General and Governor General. Barnsley, S. Yorkshire: Leo Cooper in association with Secker & Warburg. pp. 314–317.

- Marshall, Peter (September 2001). "The Balfour Formula and the Evolution of the Commonwealth". The Round Table. 90 (361): 541–53. doi:10.1080/00358530120082823.

- Baker, Philip Noel (1929). The Present Juridical Status of the British Dominions in International Law. London: Longmans. p. 231.

- Lloyd, Lorna. ""What's in a name?" – The curious tale of the office of High Commissioner". Archived from the original on 18 May 2008.

- Balfour, Arthur (November 1926). "Imperial Conference 1926" (PDF). Balfour Declaration. London: King's Printer. p. 4. E (I.R./26) Series. Retrieved 6 May 2009.

- Judd, Denis (9 July 1998). Empire: The British Imperial Experience from 1765 to the Present. New York: Basic Books. p. 287. ISBN 978-0-465-01954-0.

- Hillmer, Norman. "The Federal System". In Marsh, James H. (ed.). The Canadian Encyclopedia. Toronto: Historica Foundation of Canada. Archived from the original on 8 June 2011. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- Office of the Governor General of Canada. "Former Governors General: Lord Tweedsmuir of Elsfield". Queen's Printer for Canada. Retrieved 26 March 2009.

- Hillmer, Norman. "Governors General of Canada: Buchan, John, 1st Baron Tweedsmuir". In Marsh, James H. (ed.). The Canadian Encyclopedia. Toronto: Historica Foundation of Canada. Archived from the original on 3 July 2007. Retrieved 31 March 2009.

- Smith, Janet Adam (1965). John Buchanan: a Biography. Boston: Little Brown and Company. p. 423.

- "Royal Visit". Time. New York: Time Inc. IXX (17). 21 October 1957. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 29 March 2009.

- Office of the Governor General of Canada. "Former Governors General: Major General The Earl of Athlone". Queen's Printer for Canada. Retrieved 24 March 2009.

- Galbraith, William (February 2002). "The Canadian and the Crown". Ottawa Citizen. Archived from the original on 20 November 2008. Retrieved 19 March 2009.

- Office of the Governor General of Canada. "Former Governors General: General The Right Honourable Georges Philias Vanier". Queen's Printer for Canada. Retrieved 5 June 2009.

- Hubbard 1977, p. 233

- Office of the Governor General of Canada. "Former Governors General: The Right Honourable Daniel Roland Michener". Queen's Printer for Canada. Retrieved 5 June 2009.

- Berton, Pierre (1997). 1967: The Last Good Year. Toronto: Doubleday Canada Limited. pp. 300–312. ISBN 0-385-25662-0.

- Speaker of the Senate. "Canada: a Constitutional Monarchy". Queen's Printer for Canada. Archived from the original on 17 June 2008. Retrieved 5 June 2009.

- Department of Canadian Heritage (2005). "The Crown in Canada". Queen's Printer for Canada. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Heinricks, Geoff (2001). "Opinion: Trudeau and the Monarchy". Canadian Monarchist News. Toronto: Monarchist League of Canada (reprinted courtesy National Post) (published July 2001). Archived from the original on 22 June 2008. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

- Smith, David (1999). Watson, William (ed.). "Republican Tendencies" (PDF). Policy Options (May 1999). Montreal: Institute for Research on Public Policy. p. 8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 February 2012. Retrieved 10 February 2009.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pepall, John (1 March 1990). "Who is the Governor General?". The Idler. Toronto. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2010.

- Valpy, Michael. Watson, William (ed.). "Don't Mess With Success – and Good Luck Trying" (PDF). Policy Options (May 1999). Montreal: Institute for Research on Public Policy. p. 26. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 February 2012. Retrieved 17 February 2009.

- Smith 1999, p. 11

- Phillips, Stephen. "Republicanism in Canada in the reign of Elizabeth II: the dog that didn't bark" (PDF). Canadian Monarchist News. Toronto: Monarchist League of Canada. Summer 2004 (22): 19–20. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2009. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

- Elizabeth II (17 April 1982). Constitution Act, 1982. V.41.a. Ottawa: Queen's Printer for Canada. Archived from the original on 20 March 2007. Retrieved 5 June 2009.

- Jackson, Michael (2002). "Political Paradox: The Lieutenant Governor in Saskatchewan". In Leeson, Howard A. (ed.). Saskatchewan Politics Into the 21st Century. Regina: Canadian Plains Research Center.

- Gardner, Dan (17 February 2009). "A stealth campaign against the Queen". Calgary Herald. Archived from the original on 17 June 2009. Retrieved 26 February 2009.

- Miranda, Charles (2 March 2009). "Duchess of York Sarah Ferguson on love in royal palace". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 6 June 2009.

- Fidelis (1999). "The LeBlanc Years: A Frank Assessment". Canadian Monarchist News. Toronto: Monarchist League of Canada. Autumn 1999. Archived from the original on 8 July 2009. Retrieved 2 March 2009.

- Toffoli, Gary. "The Hnatyshyn Years". Monarchy Canada. Toronto: Fealty Enterprises (Spring 1995). Archived from the original on 12 October 2006. Retrieved 19 March 2009.

- Martin, Don (28 May 2009). "Jean is now least boring G-G ever". National Post. Archived from the original on 23 October 2014. Retrieved 25 February 2016.