Canadian identity

Canadian identity refers to the unique culture, characteristics and condition of being Canadian, as well as the many symbols and expressions that set Canada and Canadians apart from other peoples and cultures of the world.

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Canada |

|---|

|

| History |

| Topics |

| Research |

|

Primary influences on the Canadian identity trace back to the arrival, beginning in the early seventeenth century, of French settlers in Acadia and the St. Lawrence River Valley and English, Scottish and other settlers in Newfoundland, the British conquest of New France in 1759, and the ensuing dominance of French and British culture in the gradual development of both an imperial and a national identity.

Throughout the 16th, 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, First Nations played a critical part in the development of European colonies in Canada, from their role in assisting exploration of the continent, the fur trade and inter-European power struggles to the creation of the Métis people. Carrying through the 20th century and to the present day, Canadian aboriginal art and culture continues to exert a marked influence on Canadian identity.

The question of Canadian identity was traditionally dominated by two fundamental themes: first, the often conflicted relations between English Canadians and French Canadians stemming from the French Canadian imperative for cultural and linguistic survival; secondly, the generally close ties between English Canadians and the British Empire, resulting in a gradual political process towards complete independence from the imperial power. With the gradual loosening of political and cultural ties to Britain in the twentieth century, immigrants from Europe, Asia, Africa and the Caribbean have reshaped the Canadian identity, a process that continues today with the continuing arrival of large numbers of immigrants from non British or French backgrounds, adding the theme of multiculturalism to the debate.[1][2][3] Today, Canada has a diverse makeup of ethnicities and cultures (see Canadian culture) and constitutional protection for policies that promote multiculturalism rather than a single national myth.[4]

Basic models

In defining a Canadian identity, some distinctive characteristics that have been emphasized are:

- The bicultural nature of Canada and the important ways in which English–French relations since the 1760s have shaped the Canadian experience.[5]

- Canada's distinctive historical experience in resisting revolution and republicanism compared to the U.S., leading to less individualism and more support for government activism, such as wheat pools and the health care system.[6]

- The relationship to the British parliamentary system and the British legal system, the conservatism associated with the Loyalists and the pre-1960 French Canadians, have given Canada its ongoing collective obsession with "peace, order and good government".[6]

- The social structure of multiple ethnic groups that kept their identities and produced a cultural mosaic rather than a melting pot.[7]

- The influence of geographical factors (vast area, coldness, northness; St. Lawrence spine) together with the proximity of the United States have produced in the collective Canadian psyche what Northrop Frye has called the garrison mind or siege mentality, and what novelist Margaret Atwood has argued is the Canadian preoccupation with survival.[8] For Herschel Hardin, because of the remarkable hold of the siege mentality and the concern with survival, Canada in its essentials is "a public enterprise country." According to Hardin, the "fundamental mode of Canadian life" has always been, "the un-American mechanism of redistribution as opposed to the mystic American mechanism of market rule." Most Canadians, in other words, whether on the right or left in politics, expect their governments to be actively involved in the economic and social life of the nation.[9]

Historical development

Introduction

Canada's large geographic size, the presence and survival of a significant number of indigenous peoples, the conquest of one European linguistic population by another and relatively open immigration policy have led to an extremely diverse society.

Indigenous peoples

The indigenous peoples of Canada are divided among a large number of different ethnolinguistic groups, including the Inuit in the northern territory of Nunavut, the Algonquian language groups in eastern Canada (Mi'kmaq in the Maritime Provinces, Abenaki of Quebec and Ojibway of the central region), the Iroquois of central Canada, the Cree of northern Ontario, Quebec and the Great Plains, peoples speaking the Athabaskan languages of Canada's northwest, the Salishan language groups of British Columbia and other peoples of the Pacific coast such as the Tsimshian, Haida, Kwakwaka'wakw and Nuu-chah-nulth.[10] Each of the indigenous peoples developed vibrant societies with complex economies, political structures and cultural traditions that were subsequently affected profoundly by interaction with the European populations. The Metis are an indigenous people whose culture and identity was produced by a fusion of First Nations with the French, Irish and Scottish fur trade society of the north and west.

French settlement and the struggle for francophone identity in Canada

From the founding by Pierre Dugua, Sieur de Mons of Port Royal in 1605, (the beginnings of French settlement of Acadia) and the founding of Quebec City in 1608 by Samuel de Champlain, Canada was ruled from and settled almost exclusively by French colonists. John Ralston Saul, among others, has noted that the east–west shape of modern Canada had its origins in decisions regarding alliances with the indigenous peoples made by early French colonizers or explorers such as Champlain or De La Vérendrye. By allying with the Algonquins, for example, Champlain gained an alliance with the Wyandot or Huron of today's Ontario, and the enmity of the Iroquois of what is now northern New York State.[11]

Although English settlement began in Newfoundland in 1610, and the Hudson's Bay Company was chartered in 1670, it was only with the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713 that France ceded to Great Britain its claims to mainland Nova Scotia and significant British colonization of what would become mainland Canada would begin. Even then, prior to the American Revolution, Nova Scotia was settled largely by planters from New England who took up lands following the deportation of the French-speaking Acadian population, in 1755 in an event known in French to Acadians as Le Grand Dérangement, one of the critical events in the formation of the Canadian identity.[12] During the period of French hegemony over New France the term Canadien referred to the French-speaking inhabitants of Canada.

The Seven Years' War between Great Britain and France resulted in the conquest of New France by the British in 1759 at the Battle of the Plains of Abraham, an event that reverberates profoundly even today in the national consciousness of Quebecers. Although there were deliberate attempts made by the British to assimilate the French speaking population to English language and culture, most notably the 1840 Act of Union that followed the seminal report of Lord Durham, British colonial policy for Canada on the whole was one which acknowledged and permitted the continued existence of French language and culture. Nevertheless, the efforts at assimilation of French Canadians, the fate of the French-speaking Acadians and the revolt of the patriotes in 1837 would not be forgotten by their Québécois descendants. Je me souviens, (English: "I remember"), the motto of Quebec, became the watchword of the Québécois. Determined to maintain their cultural and linguistic distinctiveness in the face of British colonial domination and massive immigration of English speaking people to the pre-Confederation Province of Canada, this survivalist determination is a cornerstone of current Québécois identity and much of the political discourse in Quebec. The English Canadian writer and philosopher John Ralston Saul also considers the Ultramontane movement of Catholicism as playing a pivotal and highly negative role in the development of certain aspects of Québécois identity.[13]

British settlement in Canada: revolution, invasion and Confederation

For its part, the identity of English speaking Canada was profoundly influenced by another pivotal historic event, the American Revolution. Americans who remained loyal to the Crown and who actively supported the British during the Revolution saw their lands and goods confiscated by the new republic at the end of the war. Some 60,000 persons, known in Canada as United Empire Loyalists fled the United States or were evacuated after the war, coming to Nova Scotia and Quebec where they received land and some assistance from the British government in compensation and recognition for having taken up arms in defence of King George III and British interests. This population formed the nucleus for two modern Canadian provinces—Ontario and New Brunswick—and had a profound demographic, political and economic influence on Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and Quebec. Conservative in politics, distrustful or even hostile towards Americans, republicanism, and especially American republicanism,[14] this group of people marked the British of British North America as a distinctly identifiable cultural entity for many generations, and Canadian commentators continue to assert that the legacy of the Loyalists still plays a vital role in English Canadian identity. According to the author and political commentator Richard Gwyn while "[t]he British connection has long vanished...it takes only a short dig down to the sedimentary layer once occupied by the Loyalists to locate the sources of a great many contemporary Canadian convictions and conventions."[15]

Canada was twice invaded by armed forces from the United States during the American Revolution and the War of 1812. The first invasion occurred in 1775, and succeeded in capturing Montreal and other towns in Quebec before being repelled at Quebec City by a combination of British troops and local militia. During this invasion, the French-speaking Canadiens assisted both the invaders from the United Colonies and the defending British. The War of 1812 also saw the invasion of American forces into what was then Upper and Lower Canada, and important British victories at Queenston Heights, Lundy's Lane and Crysler's Farm. The British were assisted again by local militia, this time not only the Canadiens, but also the descendants of the Loyalists who had arrived barely a generation earlier. The Americans however captured control of Lake Erie, cutting off what is today western Ontario; they killed Tecumseh and dealt the Indian allies a decisive defeat from which they never recovered. The War of 1812 has been called "in many respects a war of independence for Canada".[16]

The years following the War of 1812 were marked by heavy immigration from Great Britain to the Canadas and, to a lesser degree, the Maritime Provinces, adding new British elements (English, Scottish and Protestant Irish) to the pre-existing English-speaking populations. During the same period immigration of Catholic Irish brought large numbers of settlers who had no attachment, and often a great hostility, toward the imperial power. The hostility of other groups to the autocratic colonial administrations that were not based on democratic principles of responsible government, principally the French-speaking population of Lower Canada and newly arrived American settlers with no particular ties to Great Britain, were to manifest themselves in the short-lived but symbolically powerful Rebellions of 1837. The term "Canadian", once describing a francophone population, was adopted by English-speaking residents of the Canadas as well, marking the process of converting 'British' immigrants into 'Canadians.'[17]

The merger of the two Canadas in 1840, with political power divided evenly between the former Lower and Upper Canadas, created a political structure that eventually exacerbated tensions between the French and English-speaking populations and which would prove an enduring feature of Canadian identity. As the population of English-speaking and largely Protestant Canada West grew to surpass that of majority French-speaking Catholic Canada East, the population of Canada West began to feel that its interests were becoming subservient to the francophone population of Canada East. George Brown, founder of The Globe newspaper (forerunner of today's The Globe and Mail) and a Father of Confederation wrote that the position of Canada West had become "a base vassalage to French-Canadian Priestcraft." [18] For its part, the French Canadians distrusted the growing anti-Catholic 'British' population of Canada West and sought a structure that could provide at least some control over its own affairs through a Provincial legislature founded on principles of responsible government.

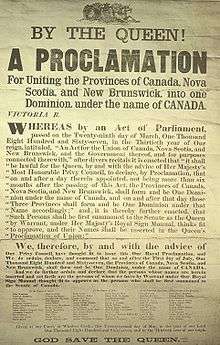

The union of the Provinces of Canada, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick into a federation in 1867 drew on all of the primary aspects of the Canadian identity: loyalty to Britain (there would be self-governance under a federal parliament, but no rupture from British institutions), limited but significant home rule for a French-speaking majority in the new Province of Quebec (and a longed for solution to English-French tensions), and a collaboration of British North Americans in order to resist the pull and the possible military threat from the United States. The republic to the south had just finished its Civil War as a powerful and united nation with little affection for Britain or its colonial baggage strung along its northern border. So great was the perceived threat that even Queen Victoria thought, prior to Confederation, that it would be "impossible" for Britain to retain Canada.[19]

In their search for an early identity, English Canadians relied heavily on loyalty and attachment to the British Empire, a triumphalist attitude towards British role in the building of Canada, as evidenced in the lyrics of the informal anthem The Maple Leaf Forever and distrust or dislike of those who were not British or Protestant. John Ralston Saul sees in the influence of the Orange Order the counterpart of the Ultramontane movement among French Canadians, leading certain groups of English Canadian Protestants to provoke persecution of the Métis and suppress or resist francophone rights.[20]

Early dominion

After Confederation, Canada became caught up in settlement of the west and extending the dominion to the Pacific Ocean. British Columbia joined Confederation in 1871. Residents of a British colony specifically established to forestall American territorial aspirations in the Fraser Valley, British Columbians were no strangers to the implications of the American doctrine of Manifest Destiny nor the economic attractions of the United States. The construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway, promised to British Columbia as an inducement to join the new dominion, became a powerful and tangible symbol of the nation's identity, linking the provinces and territories together from east to west in order to counteract the inevitable economic and cultural pull from the south.

The settlement of the west also brought to the fore the tensions between the English and French-speaking populations of Canada. The Red River Rebellion, led by Louis Riel, sought to defend the interests of French-speaking Métis against English-speaking Protestant settlers from Ontario. The controversial execution of Thomas Scott, a Protestant from Ontario, on Riel's orders and the furor that followed divided the new dominion along linguistic and religious lines. While Manitoba was created as a bilingual province in 1870 as a solution to the issue, the tensions remained, and would surface again in the Northwest Rebellion in the 1880s, when Riel led another rebellion against Ottawa.

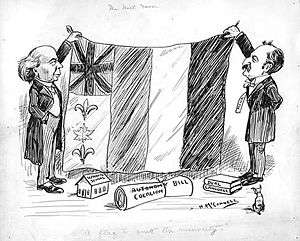

The Star, 18 April 1891[21]

From the mid to late 19th century Canada had a policy of assisting immigrants from Europe, including city people and an estimated 100,000 unwanted "Home Children" from Britain. The modern descendants of these children have been estimated at five million, contributing to Canada's identity as the "country of the abandoned".[22] Offers of free land attracted farmers from Central and Eastern Europe to the prairies,[23][24] as well as large numbers of Americans who settled to a great extent in Alberta. Several immigrant groups settled in sufficient densities to create communities of a sufficient size to exert an influence on Canadian identity, such as Ukrainian Canadians. Canada began to see itself as a country that needed and welcomed people from countries besides its traditional sources of immigrants, accepting Germans, Poles, Dutch and Scandinavians in large numbers before the First World War.

At the same time, however, concerns regarding immigration from Asian sources revealed overtly xenophobic and racist attitudes among Canadians, particularly English Canadians on the Pacific coast. At the time for many Canadian identity, whatever it was to be, did not include non-Europeans. While inexpensive Chinese labour had been needed to complete the transcontinental railway, the completion of the railway led to questions of what to do with the workers who were now no longer needed. Further Chinese immigration was limited and then banned by a series of restrictive and racially motivated dominion statutes. The Komagata Maru incident in 1914 revealed overt hostility towards would-be immigrants, mainly Sikhs from India, who attempted to land in Vancouver.

20th century

- War bond posters, 1918

Canadian victory bond poster in French. Depicts three French women pulling a plow that had been constructed for horses and men. Lithograph, adapted from a photograph.

Canadian victory bond poster in French. Depicts three French women pulling a plow that had been constructed for horses and men. Lithograph, adapted from a photograph. The same poster in English, with subtle differences in text. The French version roughly translates as 'All the world can serve' or 'Everyone can serve' and 'Let's buy victory bonds.'

The same poster in English, with subtle differences in text. The French version roughly translates as 'All the world can serve' or 'Everyone can serve' and 'Let's buy victory bonds.'

The main crisis regarding Canadian identity came in World War I. Canadians of British heritage were strongly in favour of the war effort, while those of French heritage, especially in Quebec, showed far less interest. A series of political upheavals ensued, especially the Conscription Crisis of 1917. Simultaneously, the role of immigrants as loyal Canadians was contested, with large numbers of men of German or Ukrainian heritage temporarily stripped of voting rights or incarcerated in camps. The war helped define separate political identities for the two groups, and permanently alienated Quebec and the Conservative Party.[25]

During this period, World War I helped to establish a separate Canadian identity among Anglophoners, especially through the military experiences of the Battle of Vimy Ridge and the Battle of Passchendaele and the intense homefront debates on patriotism.[26] (A similar crisis, though much less intense, erupted in World War II.)

In the 1920s, the Dominion of Canada achieved greater independence from Britain, notably in the Statute of Westminster in 1931. It remained part of the larger Commonwealth but played an independent role in the League of Nations. As Canada became increasingly independent and sovereign, its primary foreign relationship and point of reference gradually moved to the United States, the superpower with whom it shared a long border and major economic, social and cultural relationships.

The Statute of Westminster also gave Canada its own monarchy, which remains in personal union with 15 other countries of the Commonwealth of Nations. However, overt associations with British nationalism wound down after the end of the Second World War, when Canada established its own citizenship laws in 1947. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, a number of symbols of the Crown were either removed completely (such as the Royal Mail) or changed (such as the Royal Arms of Canada).

In the 1960s, Quebec experienced the Quiet Revolution to modernize society from traditional Christian teachings. Québécois nationalists demanded independence, and tensions rose until violence erupted during the 1970 October Crisis. In 1976 the Parti Québécois was elected to power in Quebec, with a nationalist vision that included securing French linguistic rights in the province and the pursuit of some form of sovereignty for Quebec, leading to a referendum in 1980 in Quebec on the question of sovereignty-association, which was turned down by 59% of the voters. At the patriation of the Canadian Constitution in 1982, the Quebec premier did not sign it; this led to two unsuccessful attempts to modify the constitution so it would be signed, and another referendum on Quebec independence in 1995 which was turned down by a small majority of 50.6%.

In 1965 Canada adopted the maple leaf flag, after considerable debate and misgivings on the part of a large number of English Canadians. Two years later the country celebrated the centennial of Confederation, with an international exposition in Montreal.

Legislative restrictions on immigration that had favoured British and other European immigrants were removed in the 1960s. By the 1970s immigrants increasingly came from India, Hong Kong, the Caribbean and Vietnam. Post-war immigrants of all backgrounds tended to settle in the major urban centres, particularly Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver.

During his long tenure in the office (1968–79, 1980–84), Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau made social and cultural change his political goal for Canada, including the pursuit of an official policy on bilingualism and plans for significant constitutional change. The west, particularly the oil and gas-producing province of Alberta, opposed many of the policies emanating from central Canada, with the National Energy Program creating considerable antagonism and growing western alienation.

Modern times

As for the role of history in national identity, the books of Pierre Berton and television series like Canada: A People's History have done much to spark the popular interest of Canadians in their history. Some commentators, such as Cohen, criticize the overall lack of attention paid by Canadians to their own history, noting a disturbing trend to ignore the broad history in favour of narrow focus on specific regions or groups.

It isn't just the schools, the museums and the government that fail us. It is also the professional historians, their books and periodicals. As J.L. Granatstein and Michael Bliss have argued, academic historians in Canada have stopped writing political and national history. They prefer to write labour history, women's history, ethnic history, and regional history, among others, often freighted with a sense of grievance or victimhood. This kind of history has its place, of course, but our history has become so specialized, so segmented, and so narrow that we are missing the national story in a country that has one and needs to hear it.[27]

Much of the debate over contemporary Canadian identity is argued in political terms, and defines Canada as a country defined by its government policies, which are thought to reflect deeper cultural values. To the political philosopher Charles Blattberg, Canada should be conceived as a civic or political community, a community of citizens, one that contains many other kinds of communities within it. These include not only communities of ethnic, regional, religious, civic (the provincial and municipal governments) and civil associational sorts, but also national communities. Blattberg thus sees Canada as a multinational country and so asserts that it contains a number of nations within it. Aside from the various aboriginal First Nations, there is also the nation of francophone Quebecers, that of the anglophones who identify with English Canadian culture, and perhaps that of the Acadians.[28]

In keeping with this, it is often asserted that Canadian government policies such as publicly funded health care, higher taxation to distribute wealth, outlawing capital punishment, strong efforts to eliminate poverty in Canada, an emphasis on multiculturalism, imposing strict gun control, leniency in regard to drug use and most recently legalizing same-sex marriage make their country politically and culturally different from the United States.[30]

In a poll that asked what institutions made Canada feel most proud about their country, number one was health care, number two was the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, and number three was peacekeeping.[31] In a CBC contest to name "The Greatest Canadian", the three highest ranking in descending order were the social democratic politician and father of medicare Tommy Douglas, the legendary cancer activist Terry Fox, and the Liberal prime minister Pierre Trudeau, responsible for instituting Canada's official policies of bilingualism and multiculturalism, which suggested that their voters valued left-of-centre political leanings and community involvement.

Most of Canada's recent prime ministers have been from Quebec, and thus have tried to improve relations with the province with a number of tactics, notably official bilingualism which required the provision of a number of services in both official languages and, among other things, required that all commercial packaging in Canada be printed in French and English. Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau's first legislative push was to implement the Royal Commission on Bilingualism within the Official languages Act in 1969. Again, while this bilingualism is a notable feature to outsiders, the plan has been less than warmly embraced by many English Canadians some of whom resent the extra administrative costs and the requirement of many key federal public servants to be fluently bilingual.[32] Despite the widespread introduction of French-language classes throughout Canada, very few anglophones are truly bilingual outside of Quebec. Pierre Trudeau in regards to uniformity stated:

Uniformity is neither desirable nor possible in a country the size of Canada. We should not even be able to agree upon the kind of Canadian to choose as a model, let alone persuade most people to emulate it. There are few policies potentially more disastrous for Canada than to tell all Canadians that they must be alike. There is no such thing as a model or ideal Canadian. What could be more absurd than the concept of an "all-Canadian" boy or girl? A society which emphasizes uniformity is one which creates intolerance and hate.[33]

In 2013, more than 90% of Canadians believed that the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and the national flag were the top symbols of Canadian identity.[34]

Migration to Canada

Canada was the home for 'American' British Loyalists during and following the American Revolution, making much of Canada distinct in its unwillingness to embrace republicanism and populist democracy during the nineteenth century. Canada was also the destination for slaves from America via the Underground Railroad (The 'North Star' as heralded by Martin Luther King Jr.); Canada was the refuge for American Vietnam draft-dodgers during the turbulent 1960s.

In response to a declining birth rate, Canada has increased the per capita immigration rate to one of the highest in the world. The economic impact of immigration to Canada is discussed as being positive by most of the Canadian media and almost all Canadian politicians.

Outsider perceptions

A very common expression of Canadian identity is to ridicule American ignorance of things Canadian.[35]

During his years with This Hour Has 22 Minutes, comic Rick Mercer produced a recurring segment, Talking to Americans. Petty says, the segment "was extraordinarily popular and was initiated by viewer demand."[35] Mercer would pose as a journalist in an American city and ask passers-by for their opinions on a fabricated Canadian news story. Some of the "stories" for which he solicited comment included the legalization of staplers, the coronation of King Svend, the border dispute between Quebec and Chechnya, the campaign against the Toronto Polar Bear Hunt, and the reconstruction of the historic "Peter Mann's Bridge". During the 2000 election in the United States, Mercer successfully staged a Talking to Americans segment in which presidential candidate George W. Bush gratefully accepted news of his endorsement by Canadian Prime Minister "Jean Poutine".[36][37]

While Canadians may dismiss comments that they do not find appealing or stereotypes that are patently ridiculous, Andrew Cohen believes that there is a value to considering what foreigners have to say: "Looking at Canadians through the eyes of foreigners, we get a sense of how they see us. They say so much about us: that we are nice, hospitable, modest, blind to our achievements. That we are obedient, conservative, deferential, colonial and complex, particularly so. That we are fractious, envious, geographically impossible and politically improbable."[38] Cohen refers in particular to the analyses of the French historian André Siegfried,[39] the Irish born journalist and novelist Brian Moore[40] or the Canadian-born American journalist Andrew H. Malcolm.[41]

French Canadians and identity in English Canada

The Canadian philosopher and writer John Ralston Saul has expressed the view that the French fact in Canada is central to Canadian, and particularly to English Canadian identity:

It cannot be repeated enough that Quebec and, more precisely, francophone Canada is at the very heart of the Canadian mythology. I don't mean that it alone constitutes the heart, which is after all a complex place. But it is at the heart and no multiple set of bypass operations could rescue that mythology if Quebec were to leave. Separation is therefore a threat of death to anglophone Canada's whole sense of itself, of its self-respect, of its role as a constituent part of a nation, of the nature of the relationship between citizens."[42]

Many Canadians believe that the relationship between the English and French languages is the central or defining aspect of the Canadian experience. Canada's Official Languages Commissioner (the federal government official charged with monitoring the two languages) has stated, "[I]n the same way that race is at the core of what it means to be American and at the core of an American experience and class is at the core of British experience, I think that language is at the core of Canadian experience."[43]

Aboriginal Canadians and Canadian identity

Saul argues that Canadian identity is founded not merely on the relationship built of French/English pragmatic compromises and cooperation but rests in fact on a triangular foundation which includes, significantly, Canada's aboriginal peoples.[44] From the reliance of French and later English explorers on Native knowledge of the country, to the development of the indigenous Métis society on the Prairies which shaped what would become Canada, and the military response to their resistance to annexation by Canada,[45] indigenous peoples were originally partners and players in laying the foundations of Canada. Individual aboriginal leaders, such as Joseph Brant or Tecumseh have long been viewed as heroes in Canada's early battles with the United States and Saul identifies Gabriel Dumont as the real leader of the Northwest Rebellion, although overshadowed by the better-known Louis Riel.[46] While the dominant culture tended to dismiss or marginalize First Nations to a large degree, individual artists such as the British Columbia painter Emily Carr, who depicted the totem poles and other carvings of the Northwest Coast peoples, helped turn the then largely ignored and undervalued culture of the first peoples into iconic images "central to the way Canadians see themselves".[47] First Nations art and iconography are now routinely integrated into public space intended to represent Canada, such as The Great Canoe", a sculpture by Haida artist Bill Reid in the courtyard of the Canadian embassy in Washington D.C. and its copy, The Spirit of Haida Gwaii, at the apex of the main hall in the Vancouver Airport.

War of 1812

The War of 1812 is often celebrated in Ontario as a British victory for what would become Canada in 1867. The Canadian government spent $28 million on three years of bicentennial events, exhibits, historic sites, re-enactments, and a new national monument.[48] The official goal was to make Canadians aware that:

- Canada would not exist had the American invasion of 1812-15 been successful.

- The end of the war laid the foundation for Confederation and the emergence of Canada as a free and independent nation.

- Under the Crown, Canada’s society retained its linguistic and ethnic diversity, in contrast to the greater conformity demanded by the American Republic.[49]

In a 2012 poll, 25% of all Canadians ranked their victory in the War of 1812 as the second most important part of their identity after free health care (53%).[50]

Canadian historians in recent decades look at the war as a defeat for the First Nations of Canada, and also for the merchants of Montreal (who lost the fur trade of the Michigan-Minnesota area).[51] The British had a long-standing goal of building a "neutral" but pro-British Indian buffer state in the American Midwest.[52][53] They demanded a neutral Indian state at the peace conference in 1814 but failed to gain any of it because they had lost control of the region in the Battle of Lake Erie and the Battle of the Thames in 1813, where Tecumseh was killed. The British then abandoned the Indians south of the lakes. The royal elite of (what is now) Ontario gained much more power in the aftermath and used that power to repel American ideas such as democracy and republicanism, especially in those areas of Ontario settled primarily by Americans. Many of those settlers returned to the states and were replaced by immigrants from Britain who were imperial-minded.[54] W. L. Morton says the war was a "stalemate" but the Americans "did win the peace negotiations."[55] Arthur Ray says the war made "matters worse for the native people" as they lost military and political power.[56] Bumsted says the war was a stalemate but regarding the Indians "was a victory for the American expansionists."[57] Thompson and Randall say "the War of 1812's real losers were the Native peoples who had fought as Britain's ally."[58] On the other hand, the "1812 Great Canadian Victory Party will bring the War of 1812...to life," promised the sponsors of a festival in Toronto in November 2009.[59]

Multiculturalism and identity

Multiculturalism and inter-ethnic relations in Canada is relaxed and tolerant, allowing ethnic or linguistic particularism to exist unquestioned. In metropolitan areas such as Toronto and Vancouver, there is often a strong sense that multiculturalism is a normal and respectable expression of being Canadian. Canada is also considered a mosaic because of the multi-culturalism.

Supporters of Canadian multiculturalism will also argue that cultural appreciation of ethnic and religious diversity promotes a greater willingness to tolerate political differences, and multiculturalism is often cited as one of Canada's significant accomplishments and a key distinguishing element of Canadian identity. Richard Gwyn has suggested that "tolerance" has replaced "loyalty" as the touchstone of Canadian identity.[60]

On the other hand, critics of Canada's multiculturalism argue that the country's "timid" attitude towards the assimilation of immigrants has actually weakened, not strengthened Canada's national identity through factionalism. Columnist and author Richard Gwyn expresses concern that Canada's sense of self may become so weak that it might vanish altogether.[61] The indulgent attitude taken towards cultural differences is perhaps a side effect of the vexed histories of French-English and Aboriginal-settler relations, which have created a need for a civic national identity, as opposed to one based on some homogenous cultural ideal. On the other hand, concerns have been raised of the danger that "ethnic nationalism will trump civic nationalism"[62] and that Canada will leap "from colony to post-national cosmopolitan" without giving Canadians a fair chance of ever finding a centre of gravity or certain sense of Canadian identity.[63][64]

For John Ralston Saul, Canada's approach of not insisting on a single national mythology or identity is not necessarily a sign of the country's weakness, but rather its greatest success,[65] signalling a rejection of or evolution from the European mono-cultural concept of a national identity to something far more "soft" and less complex:

The essential characteristic of the Canadian public mythology is its complexity. To the extent that it denies the illusion of simplicity, it is a reasonable facsimile of reality. That makes it a revolutionary reversal of the standard nation-state myth. To accept our reality—the myth of complexity—is to live out of sync with élites in other countries, particularly those in the business and academic communities.[66]

In January 2007, Prime Minister Stephen Harper advised the creation of a new sub-ministerial cabinet portfolio with the title Canadian Identity for the first time in Canadian history, naming Jason Kenney to the position of Secretary of State for Multiculturalism and Canadian Identity.

The role of Canadian social policy and identity

In Fire and Ice: The United States, Canada and the Myth of Converging Values, the author, Michael Adams, head of the Environics polling company seeks distinctions between Canadians and Americans using polling research performed by his company as evidence. Critics of the idea of a fundamentally "liberal Canada" such as David Frum argue that the Canadian drive towards a more noticeably leftist political stance is largely due to the increasing role that Quebec plays in the Canadian government (three of the last five elected Prime Ministers have been Quebecers, four if one includes Ontarian-born Paul Martin). Quebec historically was the most conservative, religious and traditional part of Canada. Since the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s, however, it has become the most secular and social democratic region of Canada. However, it is noteworthy that many Western provinces (particularly Saskatchewan and British Columbia) also have reputations as supporting leftist and social democratic policies. For example, Saskatchewan is one of the few provinces (all in the West) to reelect social democratic governments and is the cradle of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation and its successor the New Democratic Party. Much of the energy of the early Canadian feminist movement occurred in Manitoba.

By contrast, the Conservative provincial government of Alberta has frequently quarrelled with federal administrations perceived to be dominated by "eastern liberal elites."[67] Part of this is due to what Albertans feel were federal intrusions on provincial jurisdictions such as the National Energy Program and other attempts to 'interfere' with Albertan oil resources.

Distinctly Canadian

- The search for the Canadian identity often shows some whimsical results. To outsiders, this soul-searching (or, less charitably, navel-gazing) seems tedious or absurd, inspiring the Monty Python sketch Whither Canada?

- In 1971, Peter Gzowski of CBC Radio's This Country in the Morning held a competition whose goal was to compose the conclusion to the phrase: "As Canadian as..." The winning entry was "... possible, under the circumstances." It was sent in to the program by Heather Scott.[68]

- Robertson Davies, one of Canada's best known novelists, once commented about his homeland: "Some countries you love. Some countries you hate. Canada is a country you worry about."

- Pierre Berton, a Canadian journalist and novelist, has been attributed with the quote "A Canadian is someone who knows how to make love in a canoe without tipping it", although Berton himself denied that he ever actually said or wrote this.[69]

- Prime Minister Mackenzie King quipped that Canada was a country with "not enough history, too much geography".

See also

|

|

References

- John Ralston Saul, Reflections of a Siamese Twin: Canada at the End of the 20th Century, Toronto: Viking Canada, 1997, p. 439

- Philip Resnick, The European Roots of Canadian Identity, Peterborough: Broadview Press Ltd, 2005 p. 63

- Roy McGregor, Canadians: A Portrait of a Country and Its People, Toronto: Viking Canada, 2007

- Saul,Reflections of a Siamese Twin p. 8.

- "Biculturalism", The Canadian Encyclopedia (2010) online

- Lipset (1990)

- Magocsi, (1999)

- Margaret Atwood, Survival: A Thematic Guide to Canadian Lieterature, Toronto: House of Anansi Press Limited, p. 32.

- The typology is based on George A. Rawlyk, "Politics, Religion, and the Canadian Experience: A Preliminary Probe," in Mark A. Noll, ed. Religion and American Politics: From the Colonial Period to the 1980s. 1990. pp 259-60.

- This list is not an exhaustive description of all aboriginal peoples in Canada.

- Saul, Reflections of a Siamese Twin, p. 161

- Saul describes the event as "one of the most disturbing" of Canada's "real tragedies", Saul, Reflections of a Siamese Twin, p. 31

- Saul, Reflections of a Siamese Twin, p 32 quote: "The Ultramontanes took French Canada off a relatively normal track of political and social evolution...The infection of healthy nationalism with a sectarianism that can still be felt in the negative nationalists was one of their accomplishments.

- see MacGregor, Canadians, at p. 62

- Richard Gwyn, John A: The Man Who Made Us, 2007, Random House of Canada Ltd., p. 367

- Northrop Frye, Divisions on a Ground: Essays on Canadian Culture, 1982: House of Anansi Press, p. 65.

- See for example Susanna Moodie, Roughing It in the Bush, Toronto: McClelland & Stewart Limited, 1970, p. 31: quote: "British mothers of Canadian sons!—learn to feel for their country the same enthusiasm which fills your hearts when thinking of the glory of your own. Teach them to love Canada...make your children proud of the land of their birth."

- letter from George Brown, cited in Richard Gwyn, John A: The Man Who Made Us, p. 143.

- Prior to Confederation, Queen Victoria remarked on "...the impossibility of our being able to hold Canada, but we must struggle for it; and by far the best solution would be to let it go as an independent kingdom under an English prince." quoted in Stacey, C.P. British Military Policy in the Era of Confederation, CHA Annual Report and Historical Papers 13 (1934), p. 25.

- Saul, Reflections of a Siamese Twin p. 32

- Anon (18 April 1891). "Child emigration to Canada". The Star. St Peter Port, England.

- MacGregor, Canadians, p. 231

- "Pioneers Head West". CBC News.

- Civilization.ca - Advertising for immigrants to western Canada - Introduction

- J. L. Granatstein, Broken promises: A history of conscription in Canada (1977)

- Mackenzie (2005)

- Cohen, The Unfinished Canadian, p. 84

- Blattberg, Shall We Dance? A Patriotic Politics for Canada, Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2003.

- CIHI p.119

- Bricker, Darrell; Wright, John (2005). What Canadians think-- about almost-- everything. Doubleday Canada. pp. 8–23. ISBN 0-385-65985-7.

- The Environics Institute (2010). "Focus Canada (Final Report) - Queen's University" (PDF). Queen's University. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 4, 2016. Retrieved December 12, 2015.

- Sandford F. Borins. The Language of the Skies: The Bilingual Air Traffic Control Conflict in Canada (1983) p. 244

- Hines, Pamela (August 2018). The Trumping of America: A Wake Up Call to the Free World. FriesenPress. p. 180. ISBN 978-1-5255-0934-6. -Pierre Elliott Trudeau, as cited in The Essential Trudeau, ed. Ron Graham. (pp.16 – 20)

- "The Daily — Canadian identity, 2013". www.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 2015-10-01.

- Sheila Petty, et al. Canadian cultural poesis: essays on Canadian culture (2005) p. 58

- Jonathan A. Gray, et al. Satire TV: politics and comedy in the post-network era (2009) p 178

- John Herd Thompson and Stephen J. Randall, Canada and the United States: ambivalent allies (2002) p. 311

- Cohen p. 48

- André Siegfried, Canada: An International Power; New and Revised Edition, London: Jonathan Cape, 1949 quoted in Cohen, at pp. 35-37. Siegfried noted, among other things, the stark distinction between the identities of French and English-speaking Canadians.

- Brian Moore, Canada. New York: Time-Life Books, 1963, quoted in Cohen, The Unfinished Canadianat pp. 31-33, commenting on the lack of a hero culture in Canada: "There are no heroes in the wilderness. Only fools take risks."

- Andrew H. Malcolm, The Canadians: A Probing Yet Affectionate Look at the Land and the People Markham: Fitzhenry & Whiteside Ltd., 1985, quoted in Cohen, The Unfinished Canadian at pp. 44 to 47. "Canadians always seemed to be apologizing for something. It was so ingrained."

- Saul, Reflections of a Siamese Twin, p. 293

- Official Languages Commissioner Graham Fraser is quoted in the Hill Times, August 31, 2009, p. 14.

- Saul, Reflections of a Siamese Twin p. 88.

- Saul Reflections of a Siamese Twin at p. 91

- Saul, Reflections of a Siamese Twin p. 93

- Saul, Reflections of a Siamese Twin p. 41.

- Jasper Trautsch, "Review of Whose War of 1812? Competing Memories of the Anglo-American Conflict," Reviews in History (review no. 1387) 2013; Revise 2014, accessed: 10 December 2015

- Government of Canada, "The War of 1812, Historical Overview, Did You Know?" Archived 2015-11-20 at the Wayback Machine

- Trautsch, "Review of Whose War of 1812? Competing Memories of the Anglo-American Conflict"

- "The Indians and the fur merchants of Montreal had lost in the end," says Randall White, Ontario: 1610-1985 p. 75

- Dwight L. Smith, "A North American Neutral Indian Zone: Persistence of a British Idea" Northwest Ohio Quarterly 1989 61(2-4): 46-63

- Francis M. Carroll (2001). A Good and Wise Measure: The Search for the Canadian-American Boundary, 1783-1842. U of Toronto Press. p. 24.

- Fred Landon, Western Ontario and the American Frontier (1941) p. 44; see also Gerald M. Craig, Upper Canada: The Formative Years, 1784-1841 (1963)

- Morton, Kingdom of Canada 1969 pp 206-7

- Arthur Ray in Craig Brown ed. Illustrated History of Canada (2000) p 102.

- J. M. Bumsted, Peoples of Canada (2003) 1:244-45

- John Herd Thompson and Stephen J. Randall, Canada and the United States (2008) p. 23

- There is no mention of the historians in the announcement of "Great 1812 Canadian Victory Party"

- Gwyn, The Man Who Made Us What We Are, p. 365.

- Richard Gwyn, Nationalism Without Walls: The Unbearable Lightness of Being Canadian, Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1996

- Cohen, The Unfinished Canadianp. 162

- Cohen, The Unfinished Canadian pp. 163-164

- See also: Resnick, quote: "But let us not make diversity a substitute for broader aspects of national identity or turn multiculturalism into a shibboleth because we are unwilling to reaffirm underlying values that make Canada what it has become. And those values, I repeat again, are largely European in their derivation, on both the English-speaking and French—speaking sides." at p. 64.

- Saul, p. 8.

- Saul, Reflections of a Siamese Twin, p. 9.

- Panizza 2005

- "On the origin of an aphorism", PETER GZOWSKI, 24 May 1996, The Globe and Mail, page A15

- "#AsCanadianAs 'making love in a canoe'? Not so fast". CBC News, June 21, 2013.

Bibliography

- Cohen, Andrew (2008). The Unfinished Canadian: The People We Are. Emblem ed. ISBN 978-0-7710-2286-9.

- Studin, Irvin (2006). What is a Canadian?: forty-three thought-provoking responses. Marks & Spencer. ISBN 978-0-7710-8321-1.

- Resnick, Philip (2005). The European Roots Of Canadian Identity. Peterborough, Ont.: Broadview Press. ISBN 1-55111-705-3.

- Adams, Michael. Fire and Ice (2004)

- Anderson, Alan B. Ethnicity in Canada: Theoretical Perspectives. (1981)

- Association for Canadian Studies, ed. Canadian identity: Region, country, nation : selected proceedings of the 24th Annual Conference of the Association for Canadian Studies, held at Memorial ... June 6–8, 1997 (1998)

- Bashevkin, Sylvia B. True Patriot Love: The Politics of Canadian Nationalism (1991),

- Carl Berger, The Sense of Power: Studies in the Ideas of Canadian Imperialism, 1867-1914 (1970).

- Berton, Pierre Why we act like Canadians: A personal exploration of our national character

- Charles Blattberg (2003) Shall We Dance? A Patriotic Politics for Canada. McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 0-7735-2596-3.

- John Bartlet Brebner, North Atlantic Triangle: The Interplay of Canada, the United States, and Great Britain, (1945)

- Breton, Raymond. "The production and allocation of symbolic resources: an analysis of the linguistic and ethnocultural fields in Canada." Canadian Review of Sociology and Anthropology 1984 21:123-44.

- Andrew Cohen. While Canada Slept: How We Lost Our Place in the World (2004), on foreign affairs

- Cook, Ramsay. The Maple Leaf Forever (1977), essays by historian

- Copeland, Douglas (2002) Souvenir of Canada. Douglas & McIntyre. ISBN 1-55054-917-0.

- Copeland, Douglas

- Kearney, Mark; Ray, Randy (2009). The Big Book of Canadian Trivia. Dundurn Press. ISBN 978-1-55488-417-9.

The Big Book of Canadian Trivia.

- Leslie Dawn. National Visions, National Blindness: Canadian Art and Identities in the 1920s (2007)

- Will Ferguson. Why I Hate Canadians (2007), satire

- Fleras, Angie and Jean Leonard Elliot. Multiculturalism in Canada: The Challenge of Diversity 1992 .

- Stephanie R. Golob. "North America beyond NAFTA? Sovereignty, Identity and Security in Canada-U.S. Relations." Canadian-American Public Policy. 2002. pp 1+. online version

- Hurtig, Mel. The Vanishing Country: Is It Too Late to Save Canada? (2003), left-wing perspective

- Mahmood Iqbal, "The Migration of High-Skilled Workers from Canada to the United States:Empirical Evidence and Economic Reasons" (Conference Board of Canada, 2000) online version

- Jackson, Sabine. Robertson Davies And the Quest for a Canadian National Identity (2006)

- Jones, David T., and David Kilgour. Uneasy Neighbors: Canada, The USA and the Dynamics of State, Industry and Culture (2007)

- Keohane, Kieran. Symptoms of Canada: An Essay on the Canadian Identity (1997)

- Kim, Andrew E. "The Absence of Pan-Canadian Civil Religion: Plurality, Duality, and Conflict in Symbols of Canadian Culture." Sociology of Religion. 54#3. 1993. pp 257+ online version

- Lipset, Seymour Martin, Noah Meltz, Rafael Gomez, and Ivan Katchanovski. The Paradox of American Unionism: Why Americans Like Unions More Than Canadians Do, but Join Much Less (2004)

- Lipset, Seymour Martin. Continental Divide: The Values and Institutions of the United States and Canada (1990)

- Little, J.I. . Borderland Religion: The Emergence of an English-Canadian Identity, 1792-1852 (2004)

- Mackenzie, David, ed. Canada and the First World War (2005)

- Magocsi, Paul Robert, ed. Encyclopedia of Canada's people (1999)

- Matheson, John Ross. Canada's Flag: A Search for a Country. 1980 .

- Mathews, Robin. Canadian Identity: Major Forces Shaping the Life of a People (1988)

- Moogk, Peter; La Nouvelle France: The Making of French Canada: a Cultural History (2000)

- Linda Morra. "'Like Rain Drops Rolling Down New Paint': Chinese Immigrants and the Problem of National Identity in the Work of Emily Carr." American Review of Canadian Studies. Volume: 34. Issue: 3. 2004. pp 415+. online version

- W. I. Morton. The Canadian Identity (1968)

- Francisco Panizza. Populism and the Mirror of Democracy(2005)

- Philip Resnick. The European Roots of Canadian Identity (2005)

- Peter Russell (ed.), Nationalism in Canada (1966)

- Joe Sawchuk. The Metis of Manitoba: Reformulation of an ethnic identity (1978)

- Mildred A Schwartz. Public opinion and Canadian identity (1967)

- Allan Smith. Canada - An American Nation?: Essays on Continentalism, Identity, and the Canadian Frame of Mind (1994)

- David M. Thomas, ed. Canada and the United States: Differences that Count (1990) Second Edition

- Wallin, Pamela "Current State, Future Directions: Canada - U.S. Relations" by Pamela Wallin (Canada’s Consul General to New York); April 28, 2003 Archived June 17, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- William Watson, Globalization and the Meaning of Canadian Life (1998)

- Matthias Zimmer and Angelika E. Sauer. A Chorus of Different Voices: German-Canadian Identities(1998)

- Aleksandra Ziolkowska. Dreams and reality: Polish Canadian identities (1984)

- Нохрин И.М. Общественно-политическая мысль Канады и становление национального самосознания. — Huntsville: Altaspera Publishing & Literary Agency, 2012. — 232 pp. — ISBN 978-1-105-76379-3

Further reading

- Clift, Dominique, The Secret Kingdom: Interpretations of the Canadian Character. Toronto, Ont.: McClelland & Stewart, 1989. ISBN 0-7710-2161-5