Battle of Jumonville Glen

The Battle of Jumonville Glen, also known as the Jumonville affair, was the opening battle of the French and Indian War,[5] fought on May 28, 1754, near present-day Hopwood and Uniontown in Fayette County, Pennsylvania. A company of colonial militia from Virginia under the command of Lieutenant Colonel George Washington, and a small number of Mingo warriors led by Tanacharison (also known as "Half King"), ambushed a force of 35 Canadiens under the command of Joseph Coulon de Villiers de Jumonville.

A larger French Canadien force had driven off a small crew attempting to construct a British fort under the auspices of the Ohio Company at present-day Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, land claimed by the French. A British colonial force led by George Washington was sent to protect the fort under construction. The French Canadians sent Jumonville to warn Washington about encroaching on French-claimed territory. Washington was alerted to Jumonville's presence by Tanacharison, and they joined forces to ambush the Canadien camp. Washington's force killed Jumonville and some of his men in the ambush, and captured most of the others. The exact circumstances of Jumonville's death are a subject of historical controversy and debate.

Since Britain and France were not then at war, the event had international repercussions, and was a contributing factor in the start of the Seven Years' War in 1756. After the action, Washington retreated to Fort Necessity, where Canadien forces from Fort Duquesne compelled his surrender. The terms of Washington's surrender included a statement (written in French, a language Washington did not read) admitting that Jumonville was assassinated. This document and others were used by the French and Canadiens to level accusations that Washington had ordered Jumonville's slaying.

Background

Throughout the 1740s and early 1750s, British and Canadien traders had increasingly come into contact in the Ohio Country, including the upper watershed of the Ohio River in what is now western Pennsylvania.[6] Authorities in New France became more aggressive in their efforts to expel British traders and colonists from this area, and in 1753 began construction of a series of fortifications in the area.[7]

The French action drew the attention of not just the British, but also the Indian tribes of the area. Despite good Franco-Indian relations, British traders had become highly successful in convincing the Indians to trade with them in preference to the Canadiens, and the planned large-scale advance was not well received by all.[8] In particular, Tanacharison, a Mingo chief also known as the "Half King", became decidedly anti-French as a consequence. In a meeting with Paul Marin de la Malgue, commander of the French and Canadien construction force, the latter reportedly lost his temper, and shouted at the Indian chief, "I tell you, down the river I will go. If the river is blocked up, I have the forces to burst it open and tread under my feet all that oppose me. I despise all the stupid things you have said."[9] He then threw down some wampum that Tanacharison had offered as a good will gesture.[9] Marin died not long after, and command of the operations was turned over to Jacques Legardeur de Saint-Pierre.[10]

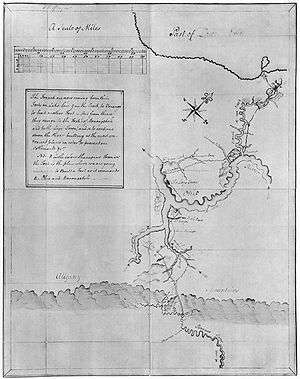

Virginia Royal Governor Robert Dinwiddie sent militia Major George Washington to the Ohio Country (a territory that was claimed by several of the British colonies, including Virginia) as an emissary in December 1753, to tell the French to leave. Saint-Pierre politely informed Washington that he was there pursuant to orders, that Washington's letter should have been addressed to his commanding officer in Canada, and that he had no intention of leaving.[11]

Washington returned to Williamsburg and informed Governor Dinwiddie that the French refused to leave.[12] Dinwiddie commissioned Washington a lieutenant colonel, and ordered him to begin raising a militia regiment to hold the Forks of the Ohio, a site Washington had identified as a fine location for a fortress.[13] The governor also issued a captain's commission to Ohio Company employee William Trent, with instructions to raise a small force and immediately begin construction of the fort. Dinwiddie issued these instructions on his own authority, without even asking for funding from the Virginia House of Burgesses until after the fact.[14] Trent's company arrived on site in February 1754, and began construction of a storehouse and stockade with the assistance of Tanacharison and the Mingos.[14][15] That same month a force of 800 Canadien militia and French troupes de la marine departed Montreal for the Ohio River valley under the command of the Canadien Claude-Pierre Pécaudy de Contrecœur, who took over command from Saint-Pierre.[16] When Contrecœur learned of Trent's activity, he led a force of about 500 men (troupes de la marine, militia, and Indians) to drive them off (rumors reaching Trent's men put its size at 1,000). On April 16, Contrecœur's force arrived at the forks; the next day, Trent's force of 36 men, led by Ensign Edward Ward in Trent's absence, agreed to leave the site.[17] The French then began construction of the fort they called Fort Duquesne.[18]

Prelude

In March 1754, Governor Dinwiddie ordered Washington back to the frontier with instructions to "act on the [defensive], but in Case any Attempts are made to obstruct the Works or interrupt our [settlements] by any Persons whatsoever, You are to restrain all such Offenders, & in Case of resistance to make Prisoners of or kill & destroy them".[19] Historian Fred Anderson describes Dinwiddie's instructions, which were issued without the knowledge or direction of the British government in London, as "an invitation to start a war".[19] Washington was ordered to gather up as many supplies and paid volunteers as he could along the way. By the time he left for the frontier on April 2, he had recruited fewer than 160 men.[20]

Along their march through the forests of the frontier, Washington was joined by more men at Winchester.[21] At this point he learned from Captain Trent of the French advance. Trent also brought a message from Tanacharison, who promised warriors to assist the British.[21] To keep Tanacharison's support, Washington decided not to turn back, choosing instead to advance. He reached a place known as the Great Meadows (now in Fayette County, Pennsylvania), about 37 miles (60 km) south of the forks, began construction of a small fort and awaited further news or instructions.[22]

Contrecœur operated under orders that forbade attacks by his force unless they were provoked. On May 23, he sent Joseph Coulon de Villiers de Jumonville with 35 soldiers (principally Canadien recruits, but also including French recruits and officers) to see if Washington had entered French territory, and with a summons to order Washington's troops out; this summons was similar in nature to the one Washington had delivered to them four months earlier.[2]

On May 27, Washington was informed by Christopher Gist, a settler who had accompanied him on the 1753 expedition, that a Canadien party numbering about 50 was in the area. In response, Washington sent 75 men with Gist to find them.[23] That evening, Washington received a message from Tanacharison, informing him that he had found the Canadien camp, and that the two of them should meet. Despite the fact that he had just sent another group in pursuit of the Canadiens, Washington went with a detachment of 40 men to meet with Tanacharison. The Mingo leader had with him 12 warriors, two of whom were boys.[1] After discussing the matter, the two leaders agreed to make an attack on the Canadiens. The attackers took up positions behind rocks around the Canadien camp, counting not more than 40 Canadiens.[1]

Battle

Exactly what happened next has been a subject of controversy and debate. The few primary accounts of the affair agree on a number of facts, and disagree on others. They agree that the battle lasted about 15 minutes, that Jumonville was killed, and that most of his party were either killed or taken prisoner.[24] According to Canadian records, most of the dead were Canadiens: Desroussel and Caron from Québec City, Charles Bois from Pointe-Claire, Jérôme from La Prairie, L'Enfant from Montréal, Paris from Mille-Isles, Languedoc and Martin from Boucherville, and LaBatterie from Trois-Rivières.[25]

Washington's accounts of the battle exist in several versions; they are consistent with each other, but the details are compressed, according to historian Fred Anderson, with intent to obscure post-battle atrocities.[26] He wrote in his diary, "We were advanced pretty near to them ... when they discovered us; whereupon I ordered my company to fire ... [Wagonner's] Company ... received the whole Fire of the French, during the greatest Part of the Action, which only lasted a Quarter of an Hour, before the Enemy was routed. We killed Mr. de Jumonville, the commander ... also nine others; we wounded one, and made Twenty-one Prisoners".[27]

Contrecœur prepared an official report of the action that was based on two sources. Most of it came from a Canadien named Monceau who escaped the action but apparently did not witness Jumonville's slaying:

Contrecœur's second source was an Indian from Tanacharison's camp, who reported that "Mr. de Jumonville was killed by a Musket-Shot in the Head, whilst they were reading the Summons".[28] The same Indian claimed that the Indians then rushed in to prevent the British from slaughtering the Frenchmen.[28]

A third account was made by a private named John Shaw who was in Washington's regiment, but not present at the affair. His account, based on detailed accounts from others who were present, was made in a sworn statement on August 21; the details on Tanacharison's role in the affair are confirmed in a newspaper account printed on June 27.[29] In his account, the French were surrounded while some still slept. Alerted by a noise, one of the Frenchmen

Shaw's narrative is substantially correct on a number of other details, including the size and composition of both forces. Shaw also claimed to have seen and counted the dead, numbering 13 or 14.[30]

Historian Anderson documents a fourth account, by a deserter from the British–Indian camp named Denis Kaninguen; Anderson speculates that he was one of Tanacharison's followers.[31] His report to the French commanders echoed that of Shaw: "notwithstanding the discharge of musket fire that [Washington] had made upon him, he [Washington] intended to read [the summons] and had withdrawn himself to his people, whom he had [previously] ordered to fire upon the French[. T]hat [Tanacharison], a savage, came up to [the wounded Jumonville] and had said, "Tu n'es pas encore mort, mon père!" [Thou art not yet dead, my father!] and struck several hatchet blows with which he killed him."[31] Anderson notes that Kaninguen apparently understood what Tanacharison said, and understood it to be a ritual slaying.[32] Kaninguen reported that 30 men were taken prisoner, and 10 to 12 had been killed.[32] The Virginians suffered only one killed and two or three wounded.[1][4]

Aftermath

Washington wrote a letter to his brother after the battle, in which he said "I can with truth assure you, I heard bullets whistle and believe me, there was something charming in the sound."[33] Following the battle, Washington returned to the Great Meadows and pushed onward the construction of a fort, which was called Fort Necessity. The dead were left on the field or buried in shallow graves, where they were later found by the French.[34]

On June 28, 1754, a combined force of 600 French, Canadien and Indian soldiers under the command of Jumonville's brother, Louis Coulon de Villiers, left Fort Duquesne.[35] On July 3, they captured Fort Necessity in the Battle of the Great Meadows, forcing Washington to negotiate a withdrawal under arms.[36] The capitulation document Washington signed, which was written in French (a language Washington did not know how to read, and which may have been poorly translated for him), included language claiming that Jumonville and his men were assassinated.[37]

Escalation

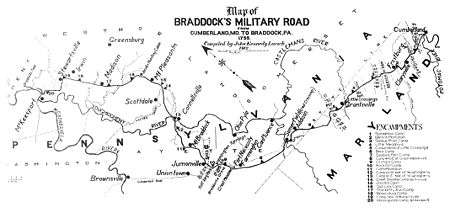

When news of the two battles reached England in August, the government of the Duke of Newcastle, after several months of negotiations, sent an army expedition the following year to dislodge the French.[38] Major General Edward Braddock was chosen to lead the expedition.[39] He was defeated at the Battle of the Monongahela, and the French remained in control of Fort Duquesne until 1758, when an expedition under General John Forbes finally succeeded in taking the fort.[40]

Word of the British military plans leaked to France well before Braddock's departure for North America, and King Louis XV dispatched a much larger body of troops to Canada in 1755.[41] Although they arrived too late to participate in Braddock's defeat, the French troop presence led to a string of French victories in the following years. In a second British act of aggression, Admiral Edward Boscawen fired on the French ship Alcide in a naval action on June 8, 1755, capturing her and two troop ships carrying some of those troops.[42] Military matters escalated on both North American soil and at sea until France and Britain declared war on each other in spring 1756, marking the formal start of the Seven Years' War.[43]

Propaganda and analysis

Because of the inconsistent nature of the record of the action, contemporary and historical coverage of it has been easily colored by preferences for one account over another. Francis Parkman, for example, accepted Washington's account, and was highly dismissive of the accounts by Monceau and the Indian.[44]

French authorities assembled a dossier of documents to counter British accounts of the affair. Entitled "Mémoire contenant le précis des faits, avec leurs pièces justificatives, pour servir de réponse aux 'Observations' envoyées par les Ministres d'Angleterre, dans les cours de l'Europe", a copy was intercepted in 1756, translated, and published as "A memorial containing a summary view of facts, with their authorities, in answer to observations sent by the English ministry to the courts of Europe".[45] It used Washington's capitulation statement and other documents, including extracts of Washington's journal taken at Fort Necessity, to suggest that Washington had actually ordered the assassination of Jumonville.[46] But not all Frenchmen agreed with the story: the Chevalier de Lévis called it a "pretended assassination".[47] The French story contrasted with that of the British account. Based on Washington's report, the British suggested that Jumonville, rather than being engaged on a diplomatic mission, was spying on them. Jumonville's orders included specific instructions to notify Contrecœur if the summons was read, so that additional forces might be sent if needed.[29][48]

Historian Fred Anderson theorizes about the reasons for Tanacharison's action in the killing, and provides a possible explanation for why one of Tanacharison's men reports the event as a British killing of a Frenchman. Tanacharison had lost influence over some of the local tribes (specifically the Delawares), and may have thought that conflict between the British and French would bring them back under his influence as allies of the British.[49] According to Parkman, after the Indians scalped the French, they sent a scalp to the Delawares, in essence offering them the opportunity to "take up the hatchet" with the British and against the French.[50]

Legacy

A portion of the battlefield, along with the Great Meadows where Fort Necessity was located, has been preserved as a part of Fort Necessity National Battlefield.[51] Jumonville's name has been given to a Christian retreat center near the site. The non-profit Braddock Road Preservation Association, named for the road General Braddock constructed to reach Fort Duquesne, sponsors research and promotes the French and Indian War history of the area.[52]

Footnotes

- Lengel, p. 37

- Lengel, p. 34

- Lengel, p. 38

- Fowler, p. 42

- Miller & Molesky, pp. 23–24

- O'Meara, pp. 10–12

- O'Meara, pp. 15–19

- O'Meara, p. 27

- O'Meara, p. 28

- O'Meara, pp. 4, 30

- O'Meara, pp. 3–5, 33

- Anderson, p. 45

- Anderson, pp. 43–45

- Anderson, p. 46

- O'Meara, p. 49

- Eccles, p. 163

- O'Meara, pp. 50–51

- Anderson, p. 49

- Anderson, p. 51

- Anderson, p. 50

- Lengel, p. 32

- Lengel, p. 33

- Lengel, p. 35

- Anderson, pp. 53–58

- Nos racines, l'histoire vivante des Québécois, Éditions Commémorative, Livre-Loisir Ltée. p458

- Anderson, p. 55

- Anderson, p. 53

- Anderson, p. 54

- Jennings, p. 69

- Anderson, p. 56

- Anderson, p. 57

- Anderson, p. 58

- Lengel, p. 39

- Lengel, p. 42

- Lengel, p. 41

- Anderson, pp. 63–64

- Lengel, p. 44

- Fowler, p. 52

- Lengel, p. 52

- Fowler, pp. 159–163

- Fowler, p. 64

- Fowler, pp. 74–75

- Fowler, p. 98

- Parkman, p. 154

- Dwight, p. 84

- Dwight, p. 85

- Parkman, p. 156

- Anderson, p. 59

- Anderson, pp. 56–57

- Parkman, p. 155

- "Fort Necessity National Battlefield: Plan Your Visit". National Park Service. Retrieved 2010-10-14.

- "Braddock Road Preservation Association". Braddock Road Preservation Association. Archived from the original on 23 November 2010. Retrieved 2010-11-23.

References

- Anderson, Fred (2000). Crucible of War: The Seven Years' War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754–1766. New York: Alfred Knopf. ISBN 978-0-375-40642-3. OCLC 237426391.

- Dwight, Theodore (February 1881). "The Journal of George Washington". The Magazine of American History. OCLC 1590082.

- Eccles, William John (1983). The Canadian Frontier, 1534–1760. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-0706-4. OCLC 239773206.

- Fowler, William M (2005). Empires at War: The French and Indian War and the Struggle for North America 1754–1763. New York: Walker & Company. ISBN 978-0-8027-7737-9. OCLC 263672663.

- Jennings, Francis (1988). Empire of Fortune: Crowns, Colonies, and Tribes in the Seven Years War in America. New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-02537-8. OCLC 16406414.

- Lengel, Edward (2005). General George Washington. New York: Random House Trade Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-8129-6950-4. OCLC 255642134.

- Miller, John J.; Molesky, Mark (18 December 2007). Our Oldest Enemy: A History of America's Disastrous Relationship with France. Random House. ISBN 9780307419187.

- O'Meara, Walter (1965). Guns at the Forks. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. OCLC 21999143.

- Parkman, Francis (1896) [1884]. Montcalm and Wolfe: Volume 1. Boston: Little, Brown. p. 155. OCLC 36673344.

Further reading

- Dinwiddie, Robert (1883). The Official Records of Robert Dinwiddie: Lieutenant-Governor of the Colony of Virginia, 1751–1758. Richmond, VA: Virginia Historical Society. OCLC 1710412.

External links

- Jumonville & Fort Necessity Includes podcast of the topic.