Hip hop

Hip hop or hip-hop is a culture and art movement that was created by African Americans, Latino Americans and Caribbean Americans in the Bronx, New York City. The origin of the name is often disputed. It is also argued as to whether hip hop started in the South or West Bronx.[1][2][3][4][5] While the term hip hop is often used to refer exclusively to hip hop music (including rap),[6] hip hop is characterized by nine elements, of which only four are considered essential to understanding hip hop musically. Afrika Bambaataa of the hip hop collective Zulu Nation outlined these main pillars of hip hop culture, coining the terms: "rapping" (also called MCing or emceeing), a rhythmic vocal rhyming style (orality); DJing (and turntablism), which is making music with record players and DJ mixers (aural/sound and music creation); b-boying/b-girling/breakdancing (movement/dance); and graffiti.[7][2][8][9][10] Other elements of hip hop subculture and arts movements beyond the main four are: hip hop culture and historical knowledge of the movement (intellectual/philosophical); beatboxing, a percussive vocal style; street entrepreneurship; hip hop language; and hip hop fashion and style, among others.[11][12][13] The fifth element, although debated, is commonly considered either street knowledge, hip hop fashion, or beatboxing.[2][7]

The Bronx hip hop scene emerged in the mid-1970s from neighborhood block parties thrown by the Black Spades, an African-American group that has been described as being a gang, a club, and a music group. Brother-sister duo Clive Campbell, a.k.a. DJ Kool Herc, and Cindy Campbell additionally hosted DJ parties in the Bronx and are credited for the rise in the genre.[14] Hip hop culture has spread to both urban and suburban communities throughout the United States and subsequently the world.[15] These elements were adapted and developed considerably, particularly as the art forms spread to new continents and merged with local styles in the 1990s and subsequent decades. Even as the movement continues to expand globally and explore myriad styles and art forms, including hip hop theater and hip hop film, the four foundational elements provide coherence and a strong foundation for hip hop culture.[2] Hip hop is simultaneously a new and old phenomenon; the importance of sampling tracks, beats, and basslines from old records to the art form means that much of the culture has revolved around the idea of updating classic recordings, attitudes, and experiences for modern audiences. Sampling older culture and reusing it in a new context or a new format is called "flipping" in hip hop culture.[16] Hip hop music follows in the footsteps of earlier African-American-rooted and Latino musical genres such as blues, jazz, rag-time, funk, salsa, and disco to become one of the most practiced genres worldwide.

In 1990, Ronald "Bee-Stinger" Savage, a former member of the Zulu Nation, is credited for coining the term "Six elements of the Hip Hop Movement," inspired by Public Enemy's recordings. The "Six Elements Of The Hip Hop Movement" are: Consciousness Awareness, Civil Rights Awareness, Activism Awareness, Justice, Political Awareness, and Community Awareness in music. Ronald Savage is known as the Son of The Hip Hop Movement.[17][18][19][20][21][22]

In the 2000s, with the rise of new media platforms such as the Internet and music streaming services, fans discovered and downloaded or streamed hip hop music through social networking sites beginning with Myspace, as well as from websites like YouTube, Worldstarhiphop, SoundCloud, and Spotify.[23][24][25]

Etymology

Keith "Cowboy" Wiggins, a member of Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, has been credited with coining the term[26] in 1978 while teasing a friend who had just joined the US Army by scat singing the made-up words "hip/hop/hip/hop" in a way that mimicked the rhythmic cadence of marching soldiers. Cowboy later worked the "hip hop" cadence into his stage performance.[27][28] The group frequently performed with disco artists who would refer to this new type of music by calling them "hip hoppers." The name was originally meant as a sign of disrespect but soon came to identify this new music and culture.[29]

The song "Rapper's Delight" by The Sugarhill Gang, released in 1979, begins with the phrase "I said a hip, hop, the hippie the hippie to the hip hip hop, and you don't stop".[30] Lovebug Starski — a Bronx DJ who put out a single called "The Positive Life" in 1981 — and DJ Hollywood then began using the term when referring to this new disco rap music. Bill Alder, an independent consultant, once said, "There was hardly ever a moment when rap music was underground, one of the very first so-called rap records, was a monster hit ('Rapper's Delight' by the Sugar Hill Gang on Sugarhill Records)."[6] Hip hop pioneer and South Bronx community leader Afrika Bambaataa also credits Love-bug Starski as the first to use the term "hip hop" as it relates to the culture. Bambaataa, former leader of the Black Spades, also did much to further popularize the term. The first use of the term in print was in a January 1982 interview of Afrika Bambaataa by Michael Holman in the East Village Eye.[31] The term gained further currency in September of that year in The Village Voice, in a profile of Bambaataa written by Steven Hager, who also published the first comprehensive history of the culture with St. Martins' Press.[27][32]

History

1970s

In the 1970s, an underground urban movement known as "hip hop" began to form in the Bronx, New York City. It focused on emceeing (or MCing) over house parties and neighborhood block party events, held outdoors. Hip hop music has been a powerful medium for protesting the impact of legal institutions on minorities, particularly police and prisons.[33] Historically, hip hop arose out of the ruins of a post-industrial and ravaged South Bronx, as a form of expression of urban Black and Latino youth, whom the public and political discourse had written off as marginalized communities.[33] Jamaican-born DJ Clive "Kool Herc" Campbell[34] pioneered the use of DJing percussion "breaks" in hip hop music. Beginning at Herc's home in a high-rise apartment at 1520 Sedgwick Avenue, the movement later spread across the entire borough.[35] On August 11, 1973 DJ Kool Herc was the DJ at his sister's back-to-school party. He extended the beat of a record by using two record players, isolating the percussion "breaks" by using a mixer to switch between the two records. Kool Herc's sister, Cindy Campbell, produced and funded the Back to School Party that became the "Birth of Hip Hop.".[36] Herc's experiments with making music with record players became what we now know as breaking or "scratching."[37]

A second key musical element in hip hop music is emceeing (also called MCing or rapping). Emceeing is the rhythmic spoken delivery of rhymes and wordplay, delivered at first without accompaniment and later done over a beat. This spoken style was influenced by the African American style of "capping," a performance where men tried to outdo each other in originality of their language and tried to gain the favor of the listeners.[38] The basic elements of hip hop—boasting raps, rival "posses" (groups), uptown "throw-downs," and political and social commentary—were all long present in African American music. MCing and rapping performers moved back and forth between the predominance of toasting songs packed with a mix of boasting, 'slackness' and sexual innuendo and a more topical, political, socially conscious style. The role of the MC originally was as a Master of Ceremonies for a DJ dance event. The MC would introduce the DJ and try to pump up the audience. The MC spoke between the DJ's songs, urging everyone to get up and dance. MCs would also tell jokes and use their energetic language and enthusiasm to rev up the crowd. Eventually, this introducing role developed into longer sessions of spoken, rhythmic wordplay, and rhyming, which became rapping.

By 1979 hip hop music had become a mainstream genre. It spread across the world in the 1990s with controversial "gangsta" rap.[39] Herc also developed upon break-beat deejaying,[40] where the breaks of funk songs—the part most suited to dance, usually percussion-based—were isolated and repeated for the purpose of all-night dance parties. This form of music playback, using hard funk and rock, formed the basis of hip hop music. Campbell's announcements and exhortations to dancers would lead to the syncopated, rhymed spoken accompaniment now known as rapping. He dubbed his dancers "break-boys" and "break-girls," or simply b-boys and b-girls. According to Herc, "breaking" was also street slang for "getting excited" and "acting energetically"[41]

DJs such as Grand Wizzard Theodore, Grandmaster Flash, and Jazzy Jay refined and developed the use of breakbeats, including cutting and scratching.[42] The approach used by Herc was soon widely copied, and by the late 1970s, DJs were releasing 12-inch records where they would rap to the beat. Influential tunes included Fatback Band's "King Tim III (Personality Jock)," The Sugarhill Gang's "Rapper's Delight," and Kurtis Blow's "Christmas Rappin'," all released in 1979.[43] Herc and other DJs would connect their equipment to power lines and perform at venues such as public basketball courts and at 1520 Sedgwick Avenue, Bronx, New York, now officially a historic building.[44] The equipment consisted of numerous speakers, turntables, and one or more microphones.[45] By using this technique, DJs could create a variety of music, but according to Rap Attack by David Toop "At its worst the technique could turn the night into one endless and inevitably boring song".[46] KC The Prince of Soul, a rapper-lyricist with Pete DJ Jones, is often credited with being the first rap lyricist to call himself an "MC."[47]

Street gangs were prevalent in the poverty of the South Bronx, and much of the graffiti, rapping, and b-boying at these parties were all artistic variations on the competition and one-upmanship of street gangs. Sensing that gang members' often violent urges could be turned into creative ones, Afrika Bambaataa founded the Zulu Nation, a loose confederation of street-dance crews, graffiti artists, and rap musicians. By the late 1970s, the culture had gained media attention, with Billboard magazine printing an article titled "B Beats Bombarding Bronx", commenting on the local phenomenon and mentioning influential figures such as Kool Herc.[48] The New York City blackout of 1977 saw widespread looting, arson, and other citywide disorders especially in the Bronx[49] where a number of looters stole DJ equipment from electronics stores. As a result, the hip hop genre, barely known outside of the Bronx at the time, grew at an astounding rate from 1977 onward.[50]

.jpg)

DJ Kool Herc's house parties gained popularity and later moved to outdoor venues in order to accommodate more people. Hosted in parks, these outdoor parties became a means of expression and an outlet for teenagers, where "instead of getting into trouble on the streets, teens now had a place to expend their pent-up energy."[51] Tony Tone, a member of the Cold Crush Brothers, stated that "hip hop saved a lot of lives".[51] For inner-city youth, participating in hip hop culture became a way of dealing with the hardships of life as minorities within America, and an outlet to deal with the risk of violence and the rise of gang culture. MC Kid Lucky mentions that "people used to break-dance against each other instead of fighting".[52] Inspired by DJ Kool Herc, Afrika Bambaataa created a street organization called Universal Zulu Nation, centered around hip hop, as a means to draw teenagers out of gang life, drugs and violence.[51]

The lyrical content of many early rap groups focused on social issues, most notably in the seminal track "The Message" (1982) by Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, which discussed the realities of life in the housing projects.[53] "Young black Americans coming out of the civil rights movement have used hip hop culture in the 1980s and 1990s to show the limitations of the movement."[54] Hip hop gave young African Americans a voice to let their issues be heard; "Like rock-and-roll, hip hop is vigorously opposed by conservatives because it romanticizes violence, law-breaking, and gangs".[54] It also gave people a chance for financial gain by "reducing the rest of the world to consumers of its social concerns."[54]

In late 1979, Debbie Harry of Blondie took Nile Rodgers of Chic to such an event, as the main backing track used was the break from Chic's "Good Times".[43] The new style influenced Harry, and Blondie's later hit single from 1981 "Rapture" became the first major single containing hip hop elements by a white group or artist to hit number one on the U.S. Billboard Hot 100—the song itself is usually considered new wave and fuses heavy pop music elements, but there is an extended rap by Harry near the end.

1980s

In 1980, Kurtis Blow released his self-titled debut album featuring the single "The Breaks", which became the first certified gold rap song.[55] In 1982, Afrika Bambaataa and the Soulsonic Force released the electro-funk track "Planet Rock". Instead of simply rapping over disco beats, Bambaataa and producer Arthur Baker created an electronic sound using the Roland TR-808 drum machine and sampling from Kraftwerk.[56] "Planet Rock" is widely regarded as a turning point; fusing electro with hip hop, it was "like a light being switched on," resulting in a new genre.[57] The track also helped popularize the 808, which became a cornerstone of hip hop music;[58][58] Wired and Slate both described the machine as hip hop's equivalent to the Fender Stratocaster, which had dramatically influenced the development of rock music.[59][60] Released in 1986, Licensed to Ill by the Beastie Boys became the first rap LP to top the Billboard album chart.[61]

Other groundbreaking records released in 1982 include "The Message" by Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, "Nunk" by Warp 9, "Hip Hop, Be Bop (Don't Stop)" by Man Parrish, "Magic Wand" by Whodini, and "Buffalo Gals" by Malcolm McLaren. In 1983, Hashim created the influential electro funk tune "Al-Naafiysh (The Soul)", while Warp 9's "Light Years Away"(1983), "a cornerstone of early 80s beat box afrofuturism", introduced socially conscious themes from a Sci-Fi perspective, paying homage to music pioneer Sun Ra.[62]

Encompassing graffiti art, MCing/rapping, DJing and b-boying, hip hop became the dominant cultural movement of the minority-populated urban communities in the 1980s.[63] The 1980s also saw many artists make social statements through hip hop. In 1982, Melle Mel and Duke Bootee recorded "The Message" (officially credited to Grandmaster Flash and The Furious Five),[64] a song that foreshadowed the socially conscious statements of Run-DMC's "It's like That" and Public Enemy's "Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos".[65] During the 1980s, hip hop also embraced the creation of rhythm by using the human body, via the vocal percussion technique of beatboxing. Pioneers such as Doug E. Fresh,[66] Biz Markie and Buffy from the Fat Boys made beats, rhythm, and musical sounds using their mouth, lips, tongue, voice, and other body parts. "Human Beatbox" artists would also sing or imitate turntablism scratching or other instrument sounds.

The appearance of music videos changed entertainment: they often glorified urban neighborhoods.[67] The music video for "Planet Rock" showcased the subculture of hip hop musicians, graffiti artists, and b-boys/b-girls. Many hip hop-related films were released between 1982 and 1985, among them Wild Style, Beat Street, Krush Groove, Breakin, and the documentary Style Wars. These films expanded the appeal of hip hop beyond the boundaries of New York. By 1984, youth worldwide were embracing the hip hop culture. The hip hop artwork and "slang" of U.S. urban communities quickly found its way to Europe, as the culture's global appeal took root. The four traditional dances of hip hop are rocking, b-boying/b-girling, locking and popping, all of which trace their origins to the late 1960s or early 1970s.[68]

Women artists have also been at the forefront of the hip hop movement since its inception in the Bronx. Nevertheless, as gangsta rap became the dominant force in hip hop music, there were many songs with misogynistic (anti-women) lyrics and many music videos depicted women in a sexualized fashion. The negation of female voice and perspective is an issue that has come to define mainstream hip hop music. The recording industry is less willing to back female artists than their male counterparts, and when it does back them, often it places emphasis on their sexuality over their musical substance and artistic abilities.[69] Since the turn of the century, female hip hop artists have struggled to get mainstream attention, with only a few, such as older artists like the female duo Salt N' Pepa to more contemporary ones like Lil' Kim and Nicki Minaj, reaching platinum status.[69]

1990s

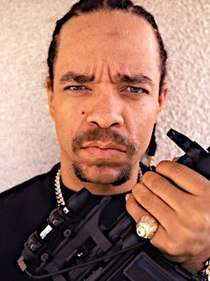

With the commercial success of gangsta rap in the early 1990s, the emphasis in lyrics shifted to drugs, violence, and misogyny. Early proponents of gangsta rap included groups and artists such as Ice-T, who recorded what some consider to be the first gangster rap single, "6 in the Mornin'",[70] and N.W.A whose second album Niggaz4Life became the first gangsta rap album to enter the charts at number one.[71] Gangsta rap also played an important part in hip hop becoming a mainstream commodity. Considering albums such as N.W.A's Straight Outta Compton, Eazy-E's Eazy-Duz-It, and Ice Cube's Amerikkka's Most Wanted were selling in such high numbers meant that black teens were no longer hip hop's sole buying audience.[72] As a result, gangsta rap became a platform for artists who chose to use their music to spread political and social messages to parts of the country that were previously unaware of the conditions of ghettos.[70] While hip hop music now appeals to a broader demographic, media critics argue that socially and politically conscious hip hop has been largely disregarded by mainstream America.[73]

Global innovations

According to the U.S. Department of State, hip hop is "now the center of a mega music and fashion industry around the world" that crosses social barriers and cuts across racial lines.[74] National Geographic recognizes hip hop as "the world's favorite youth culture" in which "just about every country on the planet seems to have developed its own local rap scene."[75] Through its international travels, hip hop is now considered a "global musical epidemic".[76] According to The Village Voice, hip hop is "custom-made to combat the anomie that preys on adolescents wherever nobody knows their name."[77]

Hip hop sounds and styles differ from region to region, but there are also instances of fusion genres.[78] Hip hop culture has grown from the avoided genre to a genre that is followed by millions of fans worldwide. This was made possible by the adaptation of music in different locations, and the influence on style of behavior and dress.[79] Not all countries have embraced hip hop, where "as can be expected in countries with strong local culture, the interloping wildstyle of hip hop is not always welcomed".[80] This is somewhat the case in Jamaica, the homeland of the culture's father, DJ Kool Herc. However, despite hip hop music produced on the island lacking widespread local and international recognition, artists such as Five Steez have defied the odds by impressing online hip hop taste-makers and even reggae critics.[81]

Hartwig Vens argues that hip hop can also be viewed as a global learning experience.[82] Author Jeff Chang argues that "the essence of hip hop is the cipher, born in the Bronx, where competition and community feed each other."[83] He also adds, "Thousands of organizers from Cape Town to Paris use hip hop in their communities to address environmental justice, policing and prisons, media justice, and education.".[84] While hip hop music has been criticized as a music that creates a divide between western music and music from the rest of the world, a musical "cross pollination" has taken place, which strengthens the power of hip hop to influence different communities.[85] Hip hop's messages allow the under-privileged and the mistreated to be heard.[82] These cultural translations cross borders.[84] While the music may be from a foreign country, the message is something that many people can relate to- something not "foreign" at all.[86]

Even when hip hop is transplanted to other countries, it often retains its "vital progressive agenda that challenges the status quo."[84] In Gothenburg, Sweden, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) incorporate graffiti and dance to engage disaffected immigrant and working class youths. Hip hop has played a small but distinct role as the musical face of revolution in the Arab Spring, one example being an anonymous Libyan musician, Ibn Thabit, whose anti-government songs fueled the rebellion.[87]

Commercialization

.jpg)

In the early-to-mid 1980s, there wasn't an established hip hop music industry, as exists in the 2020s, with record labels, record producers, managers and Artists and Repertoire staff. Politicians and businesspeople maligned and ignored the hip hop movement. Most hip hop artists performed in their local communities and recorded in underground scenes. However, in the late 1980s, music industry executives realized that they could capitalize on the success of "gangsta rap." They made a formula that created "a titillating buffet of hypermasculinity and glorified violence." This type of rap was marketed to the new fan base: white males. They ignored the depictions of a harsh reality to focus on the sex and violence involved.[88]

In an article for The Village Voice, Greg Tate argues that the commercialization of hip hop is a negative and pervasive phenomenon, writing that "what we call hiphop is now inseparable from what we call the hip hop industry, in which the nouveau riche and the super-rich employers get richer".[54] Ironically, this commercialization coincides with a decline in rap sales and pressure from critics of the genre.[89] Even other musicians, like Nas and KRS-ONE have claimed "hip hop is dead" in that it has changed so much over the years to cater to the consumer that it has lost the essence for which it was originally created.

However, in his book In Search Of Africa,[90] Manthia Diawara states that hip hop is really a voice of people who are marginalized in modern society. He argues that the "worldwide spread of hip hop as a market revolution" is actually global "expression of poor people's desire for the good life," and that this struggle aligns with "the nationalist struggle for citizenship and belonging, but also reveals the need to go beyond such struggles and celebrate the redemption of the black individual through tradition." The problem may not be that female rappers do not have the same opportunities and recognition as their male counterparts; it may be that the music industry that is so defined by gender biases. Industry executives seem to bet on the idea that men won't want to listen to female rappers, so they are given fewer opportunities.[91]

As the hip hop genre has changed since the 1980s, the African-American cultural "tradition" that Diawara describes has little place in hip hop's mainstream artists music. The push toward materialism and market success by contemporary rappers such as Rick Ross, Lil Wayne and Jay Z has irked older hip hop fans and artists. They see the genre losing its community-based feel that focused more on black empowerment than wealth. The commercialization of the genre stripped it of its earlier political nature and the politics and marketing plans of major record labels have forced rappers to craft their music and images to appeal to white, affluent and suburban audiences.

After realizing her friends were making music but not getting television exposure other than what was seen on Video Music Box, Darlene Lewis (model/lyricist), along with Darryl Washington and Dean Carroll, brought hip hop music to the First Exposure cable show on Paragon cable, and then created the On Broadway television show. There, rappers had opportunities to be interviewed and have their music videos played. This pre-dated MTV or Video Soul on BET. The commercialization has made hip hop less edgy and authentic, but it also has enabled hip hop artists to become successful.[92]

As top rappers grow wealthier and start more outside business ventures, this can indicate a stronger sense of black aspiration. As rappers such as Jay-Z and Kanye West establish themselves as artists and entrepreneurs, more young black people have hopes of achieving their goals.[93] The lens through which one views the genre's commercialization can make it seem positive or negative.[94]

White and Latino pop rappers such as Macklemore, Iggy Azalea, Machine Gun Kelly, Eminem, Miley Cyrus, G-Eazy, Pitbull, Lil Pump, and Post Malone have often been criticized for commercializing hip hop and cultural appropriation.[95] Miley Cyrus and Katy Perry, although not rappers, have been accused of cultural appropriation and commercializing hip hop. Katy Perry, a white woman, was criticized for her hip hop song "Dark Horse".[96] Taylor Swift was also accused of cultural appropriation.[97]

Culture

DJing and turntablism, MCing/rapping, breakdancing, graffiti art and beatboxing are the creative outlets that collectively make up hip hop culture and its revolutionary aesthetic. Like the blues, these arts were developed by African American communities to enable people to make a statement, whether political or emotional and participate in community activities. These practices spread globally around the 1980s as fans could "make it their own" and express themselves in new and creative ways in music, dance and other arts.[98]

DJing

DJing and turntablism are the techniques of manipulating sounds and creating music and beats using two or more phonograph turntables (or other sound sources, such as tapes, CDs or digital audio files) and a DJ mixer that is plugged into a PA system.[99] One of the first few hip hop DJs was Kool DJ Herc, who created hip hop in the 1970s through the isolation and extending of "breaks" (the parts of albums that focused solely on the percussive beat). In addition to developing Herc's techniques, DJs Grandmaster Flowers, Grandmaster Flash, Grand Wizzard Theodore, and Grandmaster Caz made further innovations with the introduction of "scratching", which has become one of the key sounds associated with hip hop music.

Traditionally, a DJ will use two turntables simultaneously and mix between the two. These are connected to a DJ mixer, an amplifier, speakers, and various electronic music equipment such as a microphone and effects units. The DJ mixes the two albums currently in rotation and/or does "scratching" by moving one of the record platters while manipulating the crossfader on the mixer. The result of mixing two records is a unique sound created by the seemingly combined sound of two separate songs into one song. Although there is considerable overlap between the two roles, a DJ is not the same as a record producer of a music track.[100] The development of DJing was also influenced by new turntablism techniques, such as beatmatching, a process facilitated by the introduction of new turntable technologies such as the Technics SL-1200 MK 2, first sold in 1978, which had a precise variable pitch control and a direct drive motor. DJs were often avid record collectors, who would hunt through used record stores for obscure soul records and vintage funk recordings. DJs helped to introduce rare records and new artists to club audiences.

In the early years of hip hop, the DJs were the stars, as they created new music and beats with their record players. While DJing and turntablism continue to be used in hip hop music in the 2010s, the star role has increasingly been taken by MCs since the late 1970s, due to innovative, creative MCs such as Kurtis Blow and Melle Mel of Grandmaster Flash's crew, the Furious Five, who developed strong rapping skills. However, a number of DJs have gained stardom nonetheless in recent years. Famous DJs include Grandmaster Flash, Afrika Bambaataa, Mr. Magic, DJ Jazzy Jeff, DJ Charlie Chase, DJ Disco Wiz, DJ Scratch from EPMD, DJ Premier from Gang Starr, DJ Scott La Rock from Boogie Down Productions, DJ Pete Rock of Pete Rock & CL Smooth, DJ Muggs from Cypress Hill, Jam Master Jay from Run-DMC, Eric B., DJ Screw from the Screwed Up Click and the inventor of the Chopped & Screwed style of mixing music, Funkmaster Flex, Tony Touch, DJ Clue, Mix Master Mike, Touch-Chill-Out, DJ Red Alert, and DJ Q-Bert. The underground movement of turntablism has also emerged to focus on the skills of the DJ. In the 2010s, there are turntablism competitions, where turntablists demonstrate advanced beat juggling and scratching skills.

MCing

Rapping (also known as emceeing,[101] MCing,[101] spitting (bars),[102] or just rhyming[103]) refers to "spoken or chanted rhyming lyrics with a strong rhythmic accompaniment".[104] Rapping typically features complex wordplay, rapid delivery, and a range of "street slang", some of which is unique to the hip hop subculture. While rapping is often done over beats, either done by a DJ, a beatboxer, it can also be done without accompaniment. It can be broken down into different components, such as "content", "flow" (rhythm and rhyme), and "delivery".[105] Rapping is distinct from spoken word poetry in that it is performed in time to the beat of the music.[106][107][108] The use of the word "rap" to describe quick and slangy speech or witty repartee long predates the musical form.[109] MCing is a form of expression that is embedded within ancient African and Indigenous culture and oral tradition as throughout history verbal acrobatics or jousting involving rhymes were common within the Afro-American and Latino-American community.[110]

Graffiti

Graffiti is the most controversial of hip hop's elements, as a number of the most notable graffiti pioneers say that they do not consider graffiti to be an element of hip hop, including Lady Pink, Seen, Blade, Fargo, Cholly Rock, Fuzz One, and Coco 144.[111][112][113] Lady Pink says, "I don't think graffiti is hip hop. Frankly I grew up with disco music. There's a long background of graffiti as an entity unto itself,"[114][115] and Fargo says, "There is no correlation between hip hop and graffiti, one has nothing to do with the other."[111][113][116] Hip hop pioneer Grandmaster Flash has also questioned the connection between hip hop and graffiti, saying, "You know what bugs me, they put hip hop with graffiti. How do they intertwine?"[116][117][118]

In America in the late 1960s, before hip hop, graffiti was used as a form of expression by political activists. In addition, gangs such as the Savage Skulls, La Familia Michoacana, and Savage Nomads used graffiti to mark territory. JULIO 204 was a Puerto Rican graffiti writer, one of the first graffiti writers in New York City. He was a member of the "Savage Skulls" gang, and started writing his nickname in his neighborhood as early as 1968. In 1971 the New York Times published an article ("'Taki 183' Spawns Pen Pals") about another graffiti writer with similar form, TAKI 183. According to the article Julio had been writing for a couple of years when Taki began tagging his own name all around the city. Taki also states in the article that Julio "was busted and stopped." Writers following in the wake of Taki and Tracy 168 would add their street number to their nickname, "bomb" (cover) a train with their work, and let the subway take it—and their fame, if it was impressive, or simply pervasive, enough—"all city". Julio 204 never rose to Taki's fame because Julio kept his tags localized to his own neighborhood.

One of the most common forms of graffiti is tagging, or the act of stylizing your unique name or logo.[119] Tagging began in Philadelphia and New York City and has expanded worldwide. Spray painting public property or the property of others without their consent can be considered vandalism, and the "tagger" may be subject to arrest and prosecution for the criminal act. Whether legal or not, the hip hop culture considers tagging buildings, trains, bridges and other structures as visual art, and consider the tags as part of a complex symbol system with its own social codes and subculture rules. Such art is in some cases now subject to federal protection in the US, making its erasure illegal.[120]

Bubble lettering held sway initially among writers from the Bronx, though the elaborate Brooklyn style Tracy 168 dubbed "wildstyle" would come to define the art.[121][122] The early trend-setters were joined in the 1970s by artists like Dondi, Futura 2000, Daze, Blade, Lee Quiñones, Fab Five Freddy, Zephyr, Rammellzee, Crash, Kel, NOC 167 and Lady Pink.[121]

The relationship between graffiti and hip hop culture arises both from early graffiti artists engaging in other aspects of hip hop culture,[123] Graffiti is understood as a visual expression of rap music, just as breaking is viewed as a physical expression. The 1983 film Wild Style is widely regarded as the first hip hop motion picture, which featured prominent figures within the New York graffiti scene during the said period. The book Subway Art and the documentary Style Wars were also among the first ways the mainstream public were introduced to hip hop graffiti. Graffiti remains part of hip hop, while crossing into the mainstream art world with exhibits in galleries throughout the world.

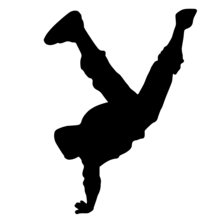

Breakdancing

Breaking, also called B-boying/B-girling or breakdancing, is a dynamic, rhythmic style of dance which developed as one of the major elements of hip hop culture. Like many aspects of hip hop culture, breakdance borrows heavily from many cultures, including 1930s-era street dancing,[124][125] Brazilian and Asian Martial arts, Russian folk dance,[126] and the dance moves of James Brown, Michael Jackson, and California funk. Breaking took form in the South Bronx in the 1970s alongside the other elements of hip hop. Breakdancing is typically done with the accompaniment of hip hop music playing on a boom box or PA system.

According to the 2002 documentary film The Freshest Kids: A History of the B-Boy, DJ Kool Herc describes the "B" in B-boy as short for breaking, which at the time was slang for "going off", also one of the original names for the dance. However, early on the dance was known as the "boing" (the sound a spring makes). Dancers at DJ Kool Herc's parties saved their best dance moves for the percussion break section of the song, getting in front of the audience to dance in a distinctive, frenetic style. The "B" in B-boy or B-girl also stands simply for break, as in break-boy or -girl. Before the 1990s, B-girls' presence was limited by their gender minority status, navigating sexual politics of a masculine-dominated scene, and a lack of representation or encouragement for women to participate in the form. The few B-girls who participated despite facing gender discrimination carved out a space for women as leaders within the breaking community, and the number of B-girls participating has increased.[127] Breaking was documented in Style Wars, and was later given more focus in fictional films such as Wild Style and Beat Street. Early acts “mainly Latino Americans” include the Rock Stea[128]dy Crew and New York City Breakers.

Beatboxing

.jpg)

Beatboxing is the technique of vocal percussion, in which a singer imitates drums and other percussion instruments with her or his voice. It is primarily concerned with the art of creating beats or rhythms using the human mouth.[129] The term beatboxing is derived from the mimicry of the first generation of drum machines, then known as beatboxes. It was first popularized by Doug E. Fresh.[130] As it is a way of creating hip hop music, it can be categorized under the production element of hip hop, though it does sometimes include a type of rapping intersected with the human-created beat. It is generally considered to be part of the same "Pillar" of hip hop as DJing—in other words, providing a musical backdrop or foundation for MC's to rap over.

Beatboxers can create their beats just naturally, but many of the beatboxing effects are enhanced by using a microphone plugged into a PA system. This helps the beatboxer to make their beatboxing loud enough to be heard alongside a rapper, MC, turntablist, and other hip hop artists. Beatboxing was popular in the 1980s with prominent artists like the Darren "Buffy, the Human Beat Box" Robinson of the Fat Boys and Biz Markie displaying their skills within the media. It declined in popularity along with b-boying in the late 1980s, but has undergone a resurgence since the late 1990s, marked by the release of "Make the Music 2000." by Rahzel of The Roots.

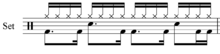

Beatmaking/producing

Although it is not described as one of the four core elements that make up hip hop, music producing is another important element. In music, record producers play a similar role in sound recording that film directors play in making a movie. The record producer recruits and selects artists (rappers, MCs, DJs, beatboxers, and so on), plans the vision for the recording session, coaches the performers on their songs, chooses audio engineers, sets out a budget for hiring the artists and technical experts, and oversees the entire project. The exact roles of a producer depend on each individual, but some producers work with DJs and drum machine programmers to create beats, coach the DJs in the selection of sampled basslines, riffs and catch phrases, give advice to rappers, vocalists, MCs and other artists, give suggestions to performers on how to improve their flow and develop a unique personal style. Some producers work closely with the audio engineer to provide ideas on mixing, effects units (e.g., Autotuned vocal effects such as those popularized by T-Pain), micing of artists, and so on. The producer may independently develop the "concept" or vision for a project or album, or develop the vision in collaboration with the artists and performers.

In hip hop, since the beginning of MCing, there have been producers who work in the studio, behind the scenes, to create the beats for MCs to rap over. Producers may find a beat they like on an old funk, soul, or disco record. They then isolate the beat and turn it into a loop. Alternatively, producers may create a beat with a drum machine or by hiring a drumkit percussionist to play acoustic drums. The producer could even mix and layer different methods, such as combining a sampled disco drum break with a drum machine track and some live, newly recorded percussion parts or a live electric bass player. A beat created by a hip hop producer may include other parts besides a drum beat, such as a sampled bassline from a funk or disco song, dialogue from a spoken word record or movie, or rhythmic "scratching" and "punches" done by a turntablist or DJ.

An early beat maker was producer Kurtis Blow, who won producer of the year credits in 1983, 1984, and 1985. Known for the creation of sample and sample loops, Blow was considered the Quincy Jones of early hip hop, a reference to the prolific African American record producer, conductor, arranger, composer, musician and bandleader. One of the most influential beat makers was J. Dilla, a producer from Detroit who chopped samples by specific beats and would combine them together to create his unique sound. Those who create these beats are known as either beat makers or producers, however producers are known to have more input and direction on the overall the creation of a song or project, while a beat maker just provides or creates the beat. As Dr. Dre has said before "Once you finish the beat, you have to produce the record."[131] The process of making beats includes sampling, "chopping", looping, sequencing beats, recording, mixing, and mastering.

Most beats in hip hop are sampled from a pre-existing record. This means that a producer will take a portion or a "sample" of a song and reuse it as an instrumental section, beat or portion of their song. Some examples of this are The Isley Brothers' "Footsteps in the Dark Pts. 1 and 2" being sampled to make Ice Cube's "Today Was a Good Day".[132] Another example is Otis Redding's "Try a Little Tenderness" being sampled to create the song "Otis", released in 2011, by Kanye West and Jay-Z.[133]

"Chopping" is dissecting the song that you are sampling so that you "chop" out the part or parts of the song, be that the bassline, rhythm guitar part, drum break, or other music, you want to use in the beat.[134] Looping is known as melodic or percussive sequence that repeats itself over a period of time, so basically a producer will make an even-number of bars of a beat (e.g., four bars or eight bars) repeat itself or "loop" of a full song length. This loop provides an accompaniment for an MC to rap over.

.jpg)

The tools needed to make beats in the late 1970s were funk, soul, and other music genre records, record turntables, DJ mixers, audio consoles, and relatively inexpensive Portastudio-style multitrack recording devices. In the 1980s and 1990s, beat makers and producers used the new electronic and digital instruments that were developed, such as samplers, sequencers, drum machines, and synthesizers. From the 1970s to the 2010s, various beat makers and producers have used live instruments, such as drum kit or electric bass on some tracks. To record the finished beats or beat tracks, beat makers and producers use a variety of sound recording equipment, typically multitrack recorders. Digital Audio Workstations, also known as DAWs, became more common in the 2010s for producers. Some of the most used DAWs are FL Studio, Ableton Live, and Pro Tools.

DAWs have made it possible for more people to be able to make beats in their own home studio, without going to a recording studio. Beat makers who own DAWs do not have to buy all the hardware that a recording studio needed in the 1980s (huge 72 channel audio consoles, multitrack recorders, racks of rackmount effects units), because 2010-era DAWs have everything they need to make beats on a good quality, fast laptop computer.[135]

Beats are such an integral part of rap music that many producers have been able to make instrumental mixtapes or albums. Even though these instrumentals have no rapping, listeners still enjoy the inventive ways the producer mixes different beats, samples and instrumental melodies. Examples of these are 9th Wonder's "Tutenkhamen" and J Dilla's "Donuts". Some hip hop records come in two versions: a beat with rapping over it, and an instrumental with just the beat. The instrumental in this case is provided so that DJs and turntablists can isolate breaks, beats and other music to create new songs.

Language

The development of hip hop linguistics is complex. Source material include the spirituals of slaves arriving in the new world, Jamaican dub music, the laments of jazz and blues singers, patterned cockney slang and radio deejays hyping their audience using rhymes.[136] Hip hop has a distinctive associated slang.[137] It is also known by alternate names, such as "Black English", or "Ebonics". Academics suggest its development stems from a rejection of the racial hierarchy of language, which held "White English" as the superior form of educated speech.[138] Due to hip hop's commercial success in the late 1990s and early 2000s, many of these words have been assimilated into the cultural discourse of several different dialects across America and the world and even to non-hip hop fans.[139] The word diss for example is particularly prolific. There are also a number of words which predate hip hop, but are often associated with the culture, with homie being a notable example. Sometimes, terms like what the dilly, yo are popularized by a single song (in this case, "Put Your Hands Where My Eyes Could See" by Busta Rhymes) and are only used briefly. One particular example is the rule-based slang of Snoop Dogg and E-40, who add -izzle or -izz to the end or middle of words.

Hip Hop lyrics have also been known for containing swear words. In particular, the word "bitch" is seen in countless songs, from NWA's "A Bitch Iz a bitch" to Missy Elliot's "She is a Bitch." It is often used in the negative connotation of a woman who is a shallow "money grubber". Some female artists have tried to reclaim the word and use it as a term of empowerment. Regardless, the hip hop community has recently taken an interest in discussing the use of the word "bitch" and whether it is necessary in rap.[140] Not only the particular words, but also the choice of which language in which rap is widely debated topic in international hip hop. In Canada, the use of non-standard variants of French, such as Franglais, a mix of French and English, by groups such as Dead Obies[141] or Chiac (such as Radio Radio[142]) has powerful symbolic implications for Canadian language politics and debates on Canadian identity. In the United States rappers choose to rap in English, Spanish, or Spanglish, depending on their own backgrounds and their intended audience.[143]

Social impact

Effects

Hip hop has made a considerable social impact since its inception in the 1970s. "Hip hop has also become relevant to the field of education because of its implications for understanding language, learning, identity, and curriculum."[144] Orlando Patterson, a sociology professor at Harvard University, helps describe the phenomenon of how hip hop has spread rapidly around the world. Patterson argues that mass communication is controlled by the wealthy, the government, and major businesses in Third World nations and countries around the world.[145] He also credits mass communication with creating a global cultural hip hop scene. As a result, the youth are influenced by the American hip hop scene and start their own forms of hip hop. Patterson believes that revitalization of hip hop music will occur around the world as traditional values are mixed with American hip hop music,[145] and ultimately a global exchange process will develop that brings youth around the world to listen to a common musical form of hip hop.

It has also been argued that rap music formed as a "cultural response to historic oppression and racism, a system for communication among black communities throughout the United States".[146] This is due to the fact that the culture reflected the social, economic and political realities of the disenfranchised youth. In the 2010s, hip hop lyrics are starting to reflect original socially conscious themes. Rappers are starting to question the government's power and its oppressive role in some societies.[147] Rap music has been a tool for political, social, and cultural empowerment outside the US. Members of minority communities—such as Algerians in France, and Turks in Germany—use rap as a platform to protest racism, poverty, and social structures.[148]

Linguistics

Hip hop lyricism has gained a measure of legitimacy in academic and literary circles. Studies of hip hop linguistics are now offered at institutions such as the University of Toronto, where poet and author George Eliot Clarke has taught the potential power of hip hop music to promote social change.[136] Greg Thomas of the University of Miami offers courses at both the undergraduate and graduate level studying the feminist and assertive nature of Lil' Kim's lyrics.[149] Some academics, including Ernest Morrell and Jeffrey Duncan-Andrade, compare hip hop to the satirical works of great "Western canon" poets of the modern era, who use imagery and create a mood to criticize society. As quoted in their work "Promoting Academic Literacy with Urban Youth Through Engaging Hip Hop Culture":

Hip hop texts are rich in imagery and metaphors and can be used to teach irony, tone, diction, and point of view. Hip hop texts can be analyzed for theme, motif, plot, and character development. Both Grand Master Flash and T.S. Eliot gazed out into their rapidly deteriorating societies and saw a "wasteland." Both poets were essentially apocalyptic in nature as they witnessed death, disease, and decay.[150]

Censorship

Hip hop music has been censored on radio and TV due to the explicit lyrics of certain genres. Many songs have been criticized for anti-establishment and sometimes violent messages. The use of profanity as well as graphic depictions of violence and sex in hip hop music videos and songs makes it hard to broadcast on television stations such as MTV, in music video form, and on radio. As a result, many hip hop recordings are broadcast in censored form, with offending language "bleeped" or blanked out of the soundtrack, or replaced with "clean" lyrics. The result – which sometimes renders the remaining lyrics unintelligible or contradictory to the original recording – has become almost as widely identified with the genre as any other aspect of the music, and has been parodied in films such as Austin Powers in Goldmember, in which Mike Myers' character Dr. Evil – performing in a parody of a hip hop music video ("Hard Knock Life (Ghetto Anthem)" by Jay-Z) – performs an entire verse that is blanked out. In 1995, Roger Ebert wrote:[151]

Rap has a bad reputation in white circles, where many people believe it consists of obscene and violent anti-white and anti-female guttural. Some of it does. Most does not. Most white listeners don't care; they hear black voices in a litany of discontent, and tune out. Yet rap plays the same role today as Bob Dylan did in 1960, giving voice to the hopes and angers of a generation, and a lot of rap is powerful writing.

In 1990, Luther Campbell and his group 2 Live Crew filed a lawsuit against Broward County Sheriff Nick Navarro, because Navarro wanted to prosecute stores that sold the group's album As Nasty As They Wanna Be because of its obscene and vulgar lyrics. In June 1990, a U.S. district court judge labeled the album obscene and illegal to sell. However, in 1992, the United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit overturned the obscenity ruling from Judge Gonzalez, and the Supreme Court of the United States refused to hear Broward County's appeal. Professor Louis Gates testified on behalf of The 2 Live Crew, arguing that the material that the county alleged was profane actually had important roots in African-American vernacular, games, and literary traditions and should be protected.[152]

—Chuck Philips, Los Angeles Times, 1992[153]

Gangsta rap is a subgenre of hip hop that reflects the violent culture of inner-city American black youths.[154] The genre was pioneered in the mid-1980s by rappers such as Schoolly D and Ice-T, and was popularized in the later part of the 1980s by groups such as N.W.A. Ice-T released "6 in the Mornin'", which is often regarded as the first gangsta rap song, in 1986. After the national attention that Ice-T and N.W.A created in the late 1980s and early 1990s, gangsta rap became the most commercially lucrative subgenre of hip hop.

N.W.A is the group most frequently associated with the founding of gangsta rap. Their lyrics were more violent, openly confrontational, and shocking than those of established rap acts, featuring incessant profanity and, controversially, use of the word "nigga". These lyrics were placed over rough, rock guitar-driven beats, contributing to the music's hard-edged feel. The first blockbuster gangsta rap album was N.W.A's Straight Outta Compton, released in 1988. Straight Outta Compton would establish West Coast hip hop as a vital genre, and establish Los Angeles as a legitimate rival to hip hop's long-time capital, New York City. Straight Outta Compton sparked the first major controversy regarding hip hop lyrics when their song "Fuck tha Police" earned a letter from FBI Assistant Director Milt Ahlerich, strongly expressing law enforcement's resentment of the song.[155][156]

Controversy surrounded Ice-T's song "Cop Killer" from the album Body Count. The song was intended to speak from the viewpoint of a criminal getting revenge on racist, brutal cops. Ice-T's rock song infuriated government officials, the National Rifle Association and various police advocacy groups.[157] Consequently, Time Warner Music refused to release Ice-T's upcoming album Home Invasion because of the controversy surrounding "Cop Killer". Ice-T suggested that the furor over the song was an overreaction, telling journalist Chuck Philips "... they've done movies about nurse killers and teacher killers and student killers. [Actor] Arnold Schwarzenegger blew away dozens of cops as the Terminator. But I don't hear anybody complaining about that." Ice-T suggested to Philips that the misunderstanding of "Cop Killer" and the attempts to censor it had racial overtones: "The Supreme Court says it's OK for a white man to burn a cross in public. But nobody wants a black man to write a record about a cop killer."[157]

The White House administrations of both George Bush senior and Bill Clinton criticized the genre.[153] "The reason why rap is under attack is because it exposes all the contradictions of American culture ... What started out as an underground art form has become a vehicle to expose a lot of critical issues that are not usually discussed in American politics. The problem here is that the White House and wanna-be's like Bill Clinton represent a political system that never intends to deal with inner city urban chaos," Sister Souljah told The Times.[153] Until its discontinuation on July 8, 2006, BET ran a late-night segment titled BET: Uncut to air nearly-uncensored videos. The show was exemplified by music videos such as "Tip Drill" by Nelly, which was criticized for what many viewed as an exploitative depiction of women, particularly images of a man swiping a credit card between a stripper's buttocks.

Public Enemy's "Gotta Give the Peeps What They Need" was censored on MTV, removing the words "free Mumia".[158] After the attack on the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001, Oakland, California group The Coup was under fire for the cover art on their album Party Music, which featured the group's two members holding a guitar tuner and two sticks[159] as the Twin Towers exploded behind them despite the fact that it was created months before the actual event. The group, having politically radical and Marxist lyrical content, said the cover meant to symbolize the destruction of capitalism. Their record label pulled the album until a new cover could be designed.

Product placement and endorsements

Critics such as Businessweek's David Kiley argue that the discussion of products within hip hop culture may actually be the result of undisclosed product placement deals.[160] Such critics allege that shilling or product placement takes place in commercial rap music, and that lyrical references to products are actually paid endorsements.[160] In 2005, a proposed plan by McDonald's to pay rappers to advertise McDonald's products in their music was leaked to the press.[160] After Russell Simmons made a deal with Courvoisier to promote the brand among hip hop fans, Busta Rhymes recorded the song "Pass the Courvoisier".[160] Simmons insists that no money changed hands in the deal.[160]

The symbiotic relationship has also stretched to include car manufacturers, clothing designers and sneaker companies,[161] and many other companies have used the hip hop community to make their name or to give them credibility. One such beneficiary was Jacob the Jeweler, a diamond merchant from New York. Jacob Arabo's clientele included Sean Combs, Lil' Kim and Nas. He created jewelry pieces from precious metals that were heavily loaded with diamond and gemstones. As his name was mentioned in the song lyrics of his hip hop customers, his profile quickly rose. Arabo expanded his brand to include gem-encrusted watches that retail for hundreds of thousands of dollars, gaining so much attention that Cartier filed a trademark-infringement lawsuit against him for putting diamonds on the faces of their watches and reselling them without permission.[162] Arabo's profile increased steadily until his June 2006 arrest by the FBI on money laundering charges.[163]

While some brands welcome the support of the hip hop community, one brand that did not was Cristal champagne maker Louis Roederer. A 2006 article from The Economist magazine featured remarks from managing director Frederic Rouzaud about whether the brand's identification with rap stars could affect their company negatively. His answer was dismissive: "That's a good question, but what can we do? We can't forbid people from buying it. I'm sure Dom Pérignon or Krug [champagne] would be delighted to have their business."[164] In retaliation, many hip hop icons such as Jay-Z and Sean Combs, who previously included references to "Cris", ceased all mentions and purchases of the champagne. 50 Cent's deal with Vitamin Water, Dr. Dre's promotion of his Beats by Dr. Dre headphone line and Dr. Pepper, and Drake's commercial with Sprite are successful deals. Although product placement deals were not popular in the 1980s, MC Hammer was an early innovator in this type of strategy. With merchandise such as dolls, commercials for soft drinks and numerous television show appearances, Hammer began the trend of rap artists being accepted as mainstream pitchpeople for brands.[165]

Media

Hip hop culture has had extensive coverage in the media, especially in relation to television; there have been a number of television shows devoted to or about hip hop, including in Europe ("H.I.P. H.O.P." in 1984). For many years, BET was the only television channel likely to play hip hop, but in recent years the channels VH1 and MTV have added a significant amount of hip hop to their play list. Run DMC became the first African American group to appear on MTV.[166][167] With the emergence of the Internet, a number of online sites began to offer hip hop related video content.

Magazines

Hip hop magazines describe hip hop's culture, including information about rappers and MCs, new hip hop music, concerts, events, fashion and history. The first hip hop publication, The Hip Hop Hit List was published in the 1980s. It contained the first rap music record chart. It was put out by two brothers from Newark, New Jersey, Vincent and Charles Carroll (who was also in a hip hop group known as The Nastee Boyz). They knew the art form very well and noticed the need for a hip hop magazine. DJs and rappers did not have a way to learn about rap music styles and labels. The periodical began as the first Rap record chart and tip sheet for DJs and was distributed through national record pools and record stores throughout the New York City Tri-State area. One of the founding publishers, Charles Carroll noted, "Back then, all DJs came into New York City to buy their records but most of them did not know what was hot enough to spend money on, so we charted it." Jae Burnett became Vincent Carroll's partner and played an instrumental role in its later development.

.jpg)

Another popular hip hop magazine that arose in the 1980s was Word Up magazine, an American magazine catering to the youth with an emphasis on hip hop. It featured articles on what is like to be a part of the hip hop community, promoted up-coming albums, bringing awareness to the projects that the artist was involved in, and also included posters of trending celebrities within the world of Hip Hop. The magazine was published monthly and mainly concerning rap, Hip Hop and R&B music. Word Up magazine was highly popular, it was even mentioned in the popular song by The Notorious B.I.G - Juicy "it was all a dream, use to read WordUp magazine". Word Up magazine was a part of pop culture.

New York tourists from abroad took the publication back home with them to other countries to share it, creating worldwide interest in the culture and new art form. It had a printed distribution of 50,000, a circulation rate of 200,000 with well over 25,000 subscribers. The "Hip Hop Hit List" was also the first to define hip hop as a culture introducing the many aspects of the art form such as fashion, music, dance, the arts and most importantly the language. For instance, on the cover the headliner included the tag "All Literature was Produced to Meet Street Comprehension!" which proved their loyalty not only to the culture but also to the streets. Most interviews were written verbatim which included their innovative broken English style of writing. Some of the early charts were written in the graffiti format tag style but was made legible enough for the masses.

The Carroll Brothers were also consultants to the many record companies who had no idea how to market hip hop music. Vincent Carroll, the magazine's creator-publisher, went on to become a huge source for marketing and promoting the culture of hip hop, starting Blow-Up Media, the first hip hop marketing firm with offices in NYC's Tribeca district. At the age of 21, Vincent Carroll employed a staff of 15 and assisted in launching some of the culture's biggest and brightest stars (the Fugees, Nelly, the Outzidaz, feat. Eminem and many more). Later other publications spawned up including: Hip Hop Connection, XXL, Scratch, The Source and Vibe.[168] Many individual cities have also produced their own local hip hop newsletters, while hip hop magazines with national distribution are found in a few other countries. The 21st century also ushered in the rise of online media, and hip hop fan sites now offer comprehensive hip hop coverage on a daily basis.

Fashion

Clothing, hair and other styles have been a big part of hip hop's social and cultural impact since the 1970s. Although the styles have changed over the decades, distinctive urban apparel and looks have been an important way for rappers, breakdancers and other hip hop community members to express themselves. As the hip hop music genre's popularity increased, so did the effect of its fashion. While there were early items synonymous with hip hop that crossed over into the mainstream culture, like Run-DMC's affinity for Adidas or the Wu-Tang Clan's championing of Clarks' Wallabees, it wasn't until its commercial peak that hip hop fashion became influential. Starting in the mid- to late 1990s, hip hop culture embraced some major designers and established a new connection with classic fashion. Brands such as Ralph Lauren, Calvin Klein and Tommy Hilfiger all tapped into hip hop culture and gave very little in return. Moving into the new millennium, hip hop fashion consisted of baggy shirts, jeans, and jerseys. As names like Pharrell and Jay-Z started their own clothing lines and still others like Kanye West linked up with designers like Louis Vuitton, the clothes got tighter, more classically fashionable, and expensive.

As hip hop has a seen a shift in the means by which its artists express their masculinity, from violence and intimidation to wealth-flaunting and entrepreneurship, it has also seen the emergence of rapper branding.[169] The modern-day hip hop artist is no longer limited to music serving as their sole occupation or source of income. By the early 1990s, major apparel companies "[had] realized the economic potential of tapping into hip hop culture ... Tommy Hilfiger was one of the first major fashion designer[s] who actively courted rappers as a way of promoting his street wear".[170] By joining forces, the artist and the corporation are able to jointly benefit from each other's resources. Hip Hop artists are trend-setters and taste-makers. Their fans range from minority groups who can relate to their professed struggles to majority groups who cannot truly relate but like to "consume the fantasy of living a more masculine life".[171] The rappers provide the "cool, hip" factor while the corporations deliver the product, advertising, and financial assets. Tommy Hilfiger, one of the first mainstream designers to actively court rappers as a way of promoting his street wear, serves a prototypical example of the hip hip/fashion collaborations:

In exchange for giving artists free wardrobes, Hilfiger found its name mentioned in both rhyming verses of rap songs and their 'shout-out' lyrics, in which rap artists chant out thanks to friends and sponsors for their support. Hilfiger's success convinced other large mainstream American fashion design companies, like Ralph Lauren and Calvin Klein, to tailor lines to the lucrative market of hip hop artists and fans.[172]

Artists now use brands as a means of supplemental income to their music or are creating and expanding their own brands that become their primary source of income. As Harry Elam explains, there has been a movement "from the incorporation and redefinition of existing trends to actually designing and marketing products as hip hop fashion".[172]

Diversification

Hip hop music has spawned dozens of subgenres which incorporate hip hop music production approaches, such as sampling, creating beats, or rapping. The diversification process stems from the appropriation of hip hop culture by other ethnic groups. There are many varying social influences that affect hip hop's message in different nations. It is frequently used as a musical response to perceived political and/or social injustices. In South Africa the largest form of hip hop is called Kwaito, which has had a growth similar to American hip hop. Kwaito is a direct reflection of a post apartheid South Africa and is a voice for the voiceless; a term that U.S. hip hop is often referred to. Kwaito is even perceived as a lifestyle, encompassing many aspects of life, including language and fashion.[173]

Kwaito is a political and party-driven genre, as performers use the music to express their political views, and also to express their desire to have a good time. Kwaito is a music that came from a once hated and oppressed people, but it is now sweeping the nation. The main consumers of Kwaito are adolescents and half of the South African population is under 21. Some of the large Kwaito artists have sold more than 100,000 albums, and in an industry where 25,000 albums sold is considered a gold record, those are impressive numbers.[174] Kwaito allows the participation and creative engagement of otherwise socially excluded peoples in the generation of popular media.[175] South African hip hop has made an impact worldwide, with performers such as Tumi, HipHop Pantsula, Tuks Senganga.[176]

In Jamaica, the sounds of hip hop are derived from American and Jamaican influences. Jamaican hip hop is defined both through dancehall and reggae music. Jamaican Kool Herc brought the sound systems, technology, and techniques of reggae music to New York during the 1970s. Jamaican hip hop artists often rap in both Brooklyn and Jamaican accents. Jamaican hip hop subject matter is often influenced by outside and internal forces. Outside forces such as the bling-bling era of today's modern hip hop and internal influences coming from the use of anti-colonialism and marijuana or "ganja" references which Rastafarians believe bring them closer to God.[177][178][179]

Author Wayne Marshall argues that "Hip hop, as with any number of African-American cultural forms before it, offers a range of compelling and contradictory significations to Jamaican artist and audiences. From "modern blackness" to "foreign mind", transnational cosmopolitanism to militant pan-Africanism, radical remixology to outright mimicry, hip hop in Jamaica embodies the myriad ways that Jamaicans embrace, reject, and incorporate foreign yet familiar forms."[180]

In the developing world, hip hop has made a considerable impact in the social context. Despite the lack of resources, hip hop has made considerable inroads.[80] Due to limited funds, hip hop artists are forced to use very basic tools, and even graffiti, an important aspect of the hip hop culture, is constrained due to its unavailability to the average person. Hip hop has begun making inroads with more than black artists. There are number of other minority artists who are taking center stage as many first generation minority children come of age. One example is rapper Awkwafina, an Asian-American, who raps about being Asian as well as being female. She, like many others, use rap to express her experiences as a minority not necessarily to "unite" minorities together but to tell her story.[181]

Many hip hop artists from the developing world come to the United States to seek opportunities. Maya Arulpragasm (A.K.A. M.I.A.), a Sri Lanka-born Tamil hip hop artist claims, "I'm just trying to build some sort of bridge, I'm trying to create a third place, somewhere in between the developed world and the developing world.".[182] Another music artist using hip hop to provide a positive message to young Africans is Emmanuel Jal, a former child soldier from South Sudan. Jal is one of the few South Sudanese music artists to have broken through on an international level[183] with his unique form of hip hop and a positive message in his lyrics.[184] Jal has attracted the attention of mainstream media and academics with his story and use of hip hop as a healing medium for war-afflicted people in Africa and he has also been sought out on the international lecture fora such as TED.[185]

Many K-Pop artists in South Korea have been influenced by hip hop and many South Korean artists perform hip hop music. In Seoul, South Korea, Koreans b-boy.[186]

Education

Scholars argue that hip hop can have an empowering effect on youth. While there is misogyny, violence, and drug use in rap music videos and lyrics, hip hop also displays many positive themes of self-reliance, resilience, and self-esteem. These messages can be inspiring for a youth living in poverty. A lot of rap songs contain references to strengthening the African American community promoting social causes. Social workers have used hip hop to build a relationship with at-risk youth and develop a deeper connection with the child.[187] Hip hop has the potential to be taught as a way of helping people see the world more critically, be it through forms of writing, creating music, or social activism. The lyrics of hip hop have been used to learn about literary devices such as metaphor, imagery, irony, tone, theme, motif, plot, and point of view.[188]

Organizations and facilities are providing spaces and programs for communities to explore making and learning about hip hop. An example is the IMP Labs in Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada. Many dance studios and colleges now offer lessons in hip hop alongside tap and ballet, as well as KRS-ONE teaching hip hop lectures at Harvard University. Hip hop producer 9th Wonder and former rapper-actor Christopher "Play" Martin from hip hop group Kid-n-Play have taught hip hop history classes at North Carolina Central University[189] and 9th Wonder has also taught a "Hip Hop Sampling Soul" class at Duke University.[190] In 2007, the Cornell University Library established a Hip Hop Collection to collect and make accessible the historical artifacts of hip hop culture and to ensure their preservation for future generations.[191]

The hip-hop community has been a major factor in educating its listeners on HIV/AIDS, a disease that has affected the community very closely. One of the biggest artists of early hip-hop Eazy-E, a member of N.W.A had died of AIDS in 1995.[192] Since then many artists, producers, choreographers and many others from many different locations have tried to make an impact and raise awareness of HIV in the hip-hop community. Many artists have made songs as sort of PSA's to raise awareness of HIV for hip-hop listeners, some songs that raise awareness are Salt N Pepa – Let's Talk About AIDS, Coolio – Too Hot and more.[193] Tanzanian artists such as Professor Jay and the group Afande Sele are notable for their contributions to this genre of hip-hop music and the awareness they have spread for HIV. [194] American writer, activist and hip-hop artist Tim'm T. West who was diagnosed with AIDS in 1999, formed queer hip-hop group Deep Dickollective who got together to rap about the HIV pandemic among queer black men and LGBTQ activism in hip-hop.[195][196] A non-profit organization out of New York City called Hip Hop 4 Life, strives to educate the youth, especially the low income youth about social and political problems in their areas of interest, which includes hip hop.[197] Hip Hop 4 Life has held many events around the New York City area to raise awareness for HIV and other problems surrounding these low income children and their communities.

Values and philosophy

Essentialism

Since the age of slavery, music has long been the language of African American identity. Because reading and writing were forbidden under the auspices of slavery, music became the only accessible form of communication. Hundreds of years later, in inner-city neighborhoods plagued by high illiteracy and dropout rates, music remains the most dependable medium of expression. Hip Hop is thus to modern day as Negro Spirituals are to the plantations of the old South: the emergent music articulates the terrors of one's environment better than written, or spoken word, thereby forging an "unquestioned association of oppression with creativity [that] is endemic" to African American culture".[198]

As a result, lyrics of rap songs have often been treated as "confessions" to a number of violent crimes in the United States.[199] It is also considered to be the duty of rappers and other hip hop artists (DJs, dancers) to "represent" their city and neighborhood. This demands being proud of being from disadvantaged cities neighborhoods that have traditionally been a source of shame, and glorifying them in lyrics and graffiti. This has potentially been one of the ways that hip hop has become regarded as a "local" rather than "foreign" genre of music in so many countries around the world in just a few decades. Nevertheless, sampling and borrowing from a number of genres and places is also a part of the hip hop milieu, and an album like the surprise hit Kala by Anglo-Tamil rapper M.I.A. was recorded in locations all across the world and features sounds from a different country on every track.[200]

According to scholar Joseph Schloss, the essentialist perspective of Hip Hop conspicuously obfuscates the role that individual style and pleasure plays in the development of the genre. Schloss notes that Hip Hop is forever fossilized as an inevitable cultural emergent, as if "none of hip-hop's innovators had been born, a different group of poor black youth from the Bronx would have developed hip-hop in exactly the same way".[198] However, while the pervasive oppressive conditions of the Bronx were likely to produce another group of disadvantaged youth, he questions whether they would be equally interested, nonetheless willing to put in as much time and energy into making music as Grandmaster Flash, DJ Kool Herc, and Afrika Bambaataa. He thus concludes that Hip Hop was a result of choice, not fate, and that when individual contributions and artistic preferences are ignored, the genre's origin becomes overly attributed to collective cultural oppression.

Authenticity

Hip hop music artists and advocates have stated that hip hop has been an authentic (true and "real") African-American artistic and cultural form since its emergence in inner-city Bronx neighborhoods in the 1970s. Some music critics, scholars and political commentators have denied hip hop's authenticity. Advocates who claim hip hop is an authentic music genre state that it is an ongoing response to the violence and discrimination experienced by black people in the United States, from the slavery that existed into the 19th century, to the lynchings of the 20th century and the ongoing racial discrimination faced by blacks.

Paul Gilroy and Alexander Weheliye state that unlike disco, jazz, R&B, house music, and other genres that were developed in the African-American community and which were quickly adopted and then increasingly controlled by white music industry executives, hip hop has remained largely controlled by African American artists, producers and executives.[202] In his book, Phonographies, Weheliye describes the political and cultural affiliations that hip hop music enables.[203] In contrast, Greg Tate states that the market-driven, commodity form of commercial hip hop has uprooted the genre from the celebration of African-American culture and the messages of protest that predominated in its early forms.[204] Tate states that the commodification and commercialization of hip hop culture undermines the dynamism of the genre for African-American communities.

These two dissenting understandings of hip hop's scope and influence frame debates that revolve around hip hop's possession of or lack of authenticity.[205] Anticipating the market arguments of Tate and others, both Gilroy and Weheliye assert that hip hop has always had a different function than Western popular music as a whole, a function that exceeds the constraints of market capitalism. Weheliye notes, "Popular music, generally in the form of recordings, has and still continues to function as one of the main channels of communication between the different geographical and cultural points in the African diaspora, allowing artists to articulate and perform their diasporic citizenship to international audiences and establish conversations with other diasporic communities."[206] For Paul Gilroy, hip hop proves an outlet of articulation and a sonic space in which African Americans can exert control and influence that they often lack in other sociopolitical and economic domains.[207]

In "Phonographies", Weheyliye explains how new sound technologies used in hip hop encourage "diasporic citizenship" and African-American cultural and political activities.[208] Gilroy states that the "power of [hip hop] music [lies] in developing black struggles by communicating information, organizing consciousness, and testing out or deploying ... individual or collective" forms of African-American cultural and political actions.[207] In the third chapter of The Black Atlantic, "Jewels Brought from Bondage: Black Music and the Politics of Authenticity", Gilroy asserts that these elements influence the production of and the interpretation of black cultural activities. What Gilroy calls the "Black Atlantic" music's rituals and traditions are a more expansive way of thinking about African-American "blackness", a way that moves beyond contemporary debates around essentialist and anti-essentialist arguments. As such, Gilroy states that music has been and remains a central staging ground for debates over the work, responsibility, and future role of black cultural and artistic production.[209]

Traditional vs. progressive views