Lisbon Strategy

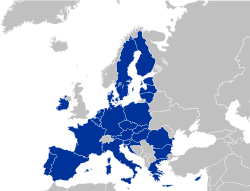

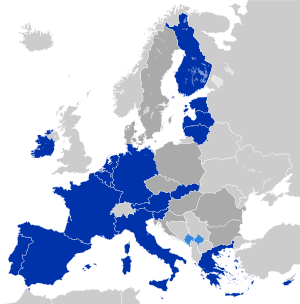

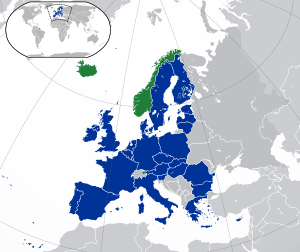

The Lisbon Strategy, also known as the Lisbon Agenda or Lisbon Process, was an action and development plan devised in 2000, for the economy of the European Union between 2000 and 2010. A pivotal role in its formulation was played by the Portuguese economist Maria João Rodrigues.

Its aim was to make the EU "the most competitive and dynamic knowledge-based economy in the world capable of sustainable economic growth with more and better jobs and greater social cohesion", by 2010.[1] It was set out by the European Council in Lisbon in March 2000. By 2010, most of its goals were not achieved. It has been succeeded by the Europe 2020 strategy.

Background and objectives

The Lisbon Strategy intended to deal with the low productivity and stagnation of economic growth in the EU, through the formulation of various policy initiatives to be taken by all EU member states. The broader objectives set out by the Lisbon strategy were to be attained by 2010.

It was adopted for a ten-year period in 2000 in Lisbon, Portugal by the European Council. It broadly aimed to "make Europe, by 2010, the most competitive and the most dynamic knowledge-based economy in the world".

Strategy

The main fields were economic, social, and environmental renewal and sustainability. The Lisbon Strategy was heavily based on the economic concepts of:

- Innovation as the motor for economic change (based on the writings of Joseph Schumpeter)

- The "learning economy"

- Social and environmental renewal

Under the strategy, a stronger economy would create employment in the EU, alongside inclusive social and environmental policies, which would themselves drive economic growth even further.

An EU research group found in 2005 that current progress had been judged "unconvincing", so a reform process was introduced wherein all goals would be reviewed every three years, with assistance provided on failing items.

Translation of the Lisbon Strategy goals into concrete measures led to the extension of the Framework Programmes for Research and Technological Development (FPs) into FP7[2] and the Joint Technology Initiatives (JTI).[3]

Key thinkers and concepts

Contemporary key thinkers on whose works the Lisbon Strategy was based and/or who were involved in its creation include Maria João Rodrigues, Christopher Freeman, Bengt-Åke Lundvall, Luc Soete, Daniele Archibugi Carlota Perez, Manuel Castells, Giovanni Dosi, and Richard Nelson.[4]

Key concepts of the Lisbon Strategy include those of the knowledge economy, innovation, techno-economic paradigms, technology governance, and the "open method of coordination" (OMC).

Midterm review

Between April and November 2004, Wim Kok headed up a review of the program and presented a report on the Lisbon strategy concluding that even if some progress was made, most of the goals were not achieved:[5]

European Union and its Member States have clearly themselves contributed to slow progress by failing to act on much of the Lisbon strategy with sufficient urgency. This disappointing delivery is due to an overloaded agenda, poor coordination and conflicting priorities. Still, a key issue has been the lack of determined political action

— [6]

The European Commission used this report as a basis for its proposal in February 2005 to refocus the Lisbon Agenda on actions that promote growth and jobs in a manner that is fully consistent with the objective of sustainable development. The Commission's communication stated that "making growth and jobs the immediate target goes hand in hand with promoting social or environmental objectives."[7]

In its resolution on the midterm review of the Lisbon strategy in March 2005, the European Parliament expressed its belief that "sustainable growth and employment are Europe's most pressing goals and underpin social and environmental progress" and "that well-designed social and environmental policies are themselves key elements in strengthening Europe's economic performance".[8]

These declarations were classed as unrealistic by some, and the failure of the "relaunch" initiative was predicted if the existing approach was not changed.[9][10][11]

Closing review

In 2009 Swedish prime minister Fredrik Reinfeldt admitted:

Even if progress has been made it must be said that the Lisbon Agenda, with only a year remaining before it is to be evaluated, has been a failure.

— [12]

The alleged failure of the Lisbon Strategy was widely commented on in the news and by member states leaders.[9][13]

Spain's prime minister José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero pointed out that the non-binding character of the Lisbon Strategy contributed to the failure, and this lesson needed to be taken into account by the new Europe 2020 strategy.[14]

Official appraisal of the Lisbon Strategy took place in March 2010 at a European Summit, where the new Europe 2020 strategy was also launched.

See also

- Europe 2020, the updated strategy for the next decade

- Economy of the European Union

- Aho report

- Community patent

- European Institute of Technology (EIT)

- Innovative Medicines Initiative

- Knowledge triangle

- Sapir Report

- Science and technology in Europe

Lobbiers

- Euroscience

- Transatlantic Business Dialogue, which took part in the report for a new restart of the agenda

- Union of Industrial and Employers' Confederations of Europe (UNICE)

- European Trade Union Confederation (ETUC)

References

- European Union Parliament Website Lisbon European Council 23 and 24 March Presidency Conclusion

- Europa.eu, European Commission - Publications Office: Understand FP7

- Europa.eu, European Commission brocure on JTIs

- The intellectual background of the Lisbon strategy has been discussed in D. Archibugi and B-A. Lundvall (eds.), The Globalising Learning Economy, Oxford University Press, 2000 and in E. Lorenz and B-A. Lundvall, How Europe's Economies Learn, Oxford University Press, 2006.

- "EurActiv, Lisbon Agenda, 2004".

- European Union web site, Facing The Challenge. The Lisbon strategy for growth and employment. Report from the High Level Group chaired by Wim Kok, November 2004, Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, ISBN 92-894-7054-2, (the Kok report).

- European Union web site, The Commission's communication.

- "Texts adopted - Wednesday, 9 March 2005 - Mid-term review of the Lisbon strategy - P6_TA(2005)0069". www.europarl.europa.eu.

- Wyplosz, Charles (12 January 2010). "The failure of the Lisbon strategy".

- Guido Tabellini, Charles Wyplosz, "Réformes structurelles et coordination en Europe", Report to the Prime Minister of France, 2004

- Guido Tabellini, Charles Wyplosz, "Annex 5 - Supply-side reforms in Europe: Can the Lisbon Strategy be repaired?", Swedish Economic Policy Review, 2006

- EurActiv, Sweden admits Lisbon Agenda 'failure', 2009

- "Do Europeans want a dynamic economy?". 8 January 2010 – via The Economist.

- "Spain calls for binding EU economic goals - and penalties - DW - 08.01.2010". DW.COM.

Further reading

- Daniele Archibugi and B-A. Lundvall (eds.) (2000), The Globalising Learning Economy, Oxford University Press.

- Maria João Rodrigues (2003), European Policies for a Knowledge Economy, Edward Elgar.

- Edward Lorenz and B-A. Lundvall (eds.) (2006),How Europe's Economies Learn, Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Maria João Rodrigues (2009), Europe, Globalization and the Lisbon Agenda in collaboration with I. Begg, J. Berghman, R. Boyer, B. Coriat, W. Drechsler, J. Goetschy, B.Å. Lundvall, P.C. Padoan, L. Soete, M. Telò and A. Török, Edward Elgar.

- Arno Tausch (2010), Titanic 2010?: The European Union and Its Failed Lisbon Strategy (European Political, Economic and Security Issues Series) Hauppauge, New York: Nova Science Publishers

- Aristovnik, Aleksander & Andrej, Pungartnik, 2009. "Analysis of reaching the Lisbon Strategy targets at the national level: the EU-27 and Slovenia", MPRA Paper 18090, University Library of Munich, Germany.

- Copeland, Paul & Papadimitriou, Dimitris (eds.) (2012) The EU's Lisbon Strategy: evaluating success, understanding failure. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

External links

- Sapir, André (2003): An Agenda for a Growing Europe, Making the EU Economic System Deliver. Report of an Independent High-Level Study Group established on the initiative of the President of the European Commission

- Euractiv background article about the Lisbon Agenda

- Stefan Collignon, Forward with Europe: a democratic and progressive reform agenda after the Lisbon strategy, Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, Internat. Politikanalyse, April 2008.

- The Economist – Charlemagne Blog: Do Europeans want a dynamic economy?

- Joachim Fritz-Vannahme, Armando García Schmidt, Dominik Hierlemann, Robert Vehrkamp: "Lisbon – A Second Shot", spotlight europe 2010/02, February 2010, Bertelsmann Stiftung (PDF, 340 kB)

- Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, Study Group Europe: Paving the way for a sustainable European prosperity strategy, February 2010 (PDF, 135 kB)

- Network of towns inspired by Lisbon Strategy

- European Trade Union Confederation update on the Lisbon strategy