Canada goose

The Canada goose (Branta canadensis) is a large wild goose species with a black head and neck, white cheeks, white under its chin, and a brown body. It is native to arctic and temperate regions of North America, and its migration occasionally reaches northern Europe. It has been introduced to the United Kingdom, Ireland, New Zealand, Argentina, Chile, and the Falkland Islands.[2] Like most geese, the Canada goose is primarily herbivorous and normally migratory; it tends to be found on or close to fresh water.

| Canada goose | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Canada goose (Branta canadensis) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Anseriformes |

| Family: | Anatidae |

| Genus: | Branta |

| Species: | B. canadensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Branta canadensis | |

| Subspecies | |

| |

| |

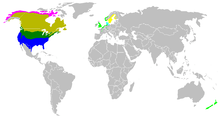

| Canada goose distribution: Summer range (native) Year-round range (native) Wintering range (native) Summer range (introduced) Year-round range (introduced) Wintering range (introduced) Summer range (cackling goose) | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Anas canadensis Linnaeus, 1758 | |

Extremely skilled at living in human-altered areas, Canada geese have established breeding colonies in urban and cultivated habitats, which provide food and few natural predators. The success of this common park species has led to its often being considered a pest species because of its excrement, its depredation of crops, its noise, its aggressive territorial behavior towards both humans and other animals, and its habit of begging for food (caused by human hand feeding).

Nomenclature and taxonomy

The Canada goose was one of the many species described by Carl Linnaeus in his 18th-century work Systema Naturae.[3] It belongs to the Branta genus of geese, which contains species with largely black plumage, distinguishing them from the grey species of the genus Anser.

Branta was a Latinised form of Old Norse Brandgás, "burnt (black) goose" and the specific epithet canadensis is a New Latin word meaning "from Canada".[4] According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the first citation for the 'Canada goose' dates back to 1772.[5][6][7] The Canada goose is also colloquially referred to as the "Canadian goose".[8] A persistent urban legend gives the name origin as after an ornithologist surnamed "Canada" but this is false.

The cackling goose was originally considered to be the same species or a subspecies of the Canada goose, but in July 2004, the American Ornithologists' Union's Committee on Classification and Nomenclature split them into two species, making the cackling goose into a full species with the scientific name Branta hutchinsii. The British Ornithologists' Union followed suit in June 2005.[9]

The AOU has divided the many subspecies between the two species. The subspecies of the Canada goose were listed as:

- Atlantic Canada goose, B. c. canadensis (Linnaeus, 1758)

- Interior Canada goose, B. c. interior (Todd, 1938)

- Giant Canada goose, B. c. maxima Delacour, 1951

- Moffitt's Canada goose, B. c. moffitti Aldrich, 1946

- Vancouver Canada goose, B. c. fulva (Delacour, 1951)

- Dusky Canada goose, B. c. occidentalis (Baird, 1858)

- Lesser Canada goose, B. c. parvipes (Cassin, 1852)

The distinctions between the two geese have led to confusion and debate among ornithologists. This has been aggravated by the overlap between the small types of Canada goose and larger types of cackling goose. The old "lesser Canada geese" were believed to be a partly hybrid population, with the birds named B. c. taverneri considered a mixture of B. c. minima, B. c. occidentalis, and B. c. parvipes. The holotype specimen of taverneri is a straightforward large pale cackling goose however, and hence the taxon is still valid today and was renamed "Taverner's cackling goose".

In addition, the barnacle goose (B. leucopsis) was determined to be a derivative of the cackling goose lineage, whereas the Hawaiian goose (B. sandvicensis) originated from ancestral Canada geese. Thus, the species' distinctness is well evidenced. A recent proposed revision by Harold C. Hanson suggests splitting Canada and cackling goose into six species and 200 subspecies. The radical nature of this proposal has provoked surprise in some quarters; Richard Banks of the AOU urges caution before any of Hanson's proposals are accepted.[10]

Description

The black head and neck with a white "chinstrap" distinguish the Canada goose from all other goose species, with the exception of the cackling goose and barnacle goose (the latter, however, has a black breast and grey rather than brownish body plumage).[11]

The seven subspecies of this bird vary widely in size and plumage details, but all are recognizable as Canada geese. Some of the smaller races can be hard to distinguish from the cackling goose, which slightly overlap in mass. However, most subspecies of the cackling goose (exclusive of Richardson's cackling goose, B. h. hutchinsii) are considerably smaller. The smallest cackling goose, B. h. minima, is scarcely larger than a mallard. In addition to the size difference, cackling geese also have a shorter neck and smaller bill, which can be useful when small Canada geese comingle with relatively large cackling geese. Of the "true geese" (i.e. the genera Anser, Branta or Chen), the Canada goose is on average the largest living species, although some other species that are geese in name, if not of close relation to these genera, are on average heavier such as the spur-winged goose and Cape Barren goose.

Canada geese range from 75 to 110 cm (30 to 43 in) in length and have a 127–185 cm (50–73 in) wingspan.[12] Among standard measurements, the wing chord can range from 39 to 55 cm (15 to 22 in), the tarsus can range from 6.9 to 10.6 cm (2.7 to 4.2 in) and the bill can range from 4.1 to 6.8 cm (1.6 to 2.7 in). The largest subspecies is the B. c. maxima, or the giant Canada goose, and the smallest (with the separation of the cackling goose group) is B. c. parvipes, or the lesser Canada goose.[13] An exceptionally large male of race B. c. maxima, which rarely exceed 8 kg (18 lb), weighed 10.9 kg (24 lb) and had a wingspan of 2.24 m (7.3 ft). This specimen is the largest wild goose ever recorded of any species.[14]

The male Canada goose usually weighs 2.6–6.5 kg (5.7–14.3 lb), averaging amongst all subspecies 3.9 kg (8.6 lb). The female looks virtually identical, but is slightly lighter at 2.4–5.5 kg (5.3–12.1 lb), averaging amongst all subspecies 3.6 kg (7.9 lb), and generally 10% smaller in linear dimensions than the male counterparts.[15] The honk refers to the call of the male Canada goose, while the hrink call refers to the female goose.[16] The calls are similar, however, the hrink is shorter and more high-pitched than the honk of males. [17]

Distribution and habitat

_(5).jpg)

This species is native to North America. It breeds in Canada and the northern United States in a wide range of habitats. The Great Lakes region maintains a very large population of Canada geese. Canada geese occur year-round in the southern part of their breeding range, including most of the eastern seaboard and the Pacific coast. Between California and South Carolina in the southern United States and northern Mexico, Canada geese are primarily present as migrants from further north during the winter.[18]

By the early 20th century, overhunting and loss of habitat in the late 19th century and early 20th century had resulted in a serious decline in the numbers of this bird in its native range. The giant Canada goose subspecies was believed to be extinct in the 1950s until, in 1962, a small flock was discovered wintering in Rochester, Minnesota, by Harold Hanson of the Illinois Natural History Survey.[19] In 1964, the Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center was built near Jamestown, North Dakota. Its first director, Harvey K. Nelson, talked Forrest Lee into leaving Minnesota to head the center's Canada goose production and restoration program. Forrest soon had 64 pens with 64 breeding pairs of screened, high-quality birds. The project involved private, state, and federal resources and relied on the expertise and cooperation of many individuals. By the end of 1981, more than 6,000 giant Canada geese had been released at 83 sites in 26 counties in North Dakota.[20] With improved game laws and habitat recreation and preservation programs, their populations have recovered in most of their range, although some local populations, especially of the subspecies B. c. occidentalis, may still be declining.

In recent years, Canada goose populations in some areas have grown substantially, so much so that many consider them pests for their droppings, bacteria in their droppings, noise, and confrontational behavior. This problem is partially due to the removal of natural predators and an abundance of safe, man-made bodies of water near food sources, such as those found on golf courses, in public parks and beaches, and in planned communities. Due in part to the interbreeding of various migratory subspecies with the introduced nonmigratory giant subspecies, Canada geese are frequently a year-around feature of such urban environments.[21]

Contrary to its normal migration routine, large flocks of Canada geese have established permanent residence along the Pacific coast of North America from south-western British Columbia (specifically Vancouver Island and British Columbia's Lower Mainland), south to the San Francisco Bay area of Northern California. There are also resident Atlantic coast populations, such as on Chesapeake Bay, in Virginia's James River regions, and in the Triangle area of North Carolina (Raleigh, Durham, Chapel Hill), and nearby Hillsborough. Some Canada geese have taken up permanent residence as far south as Florida, in places such as retention ponds in apartment complexes. In 2015, the Ohio population of Canada geese was reported as roughly 130,000, with the number likely to continue increasing. Many of the geese, previously migratory, reportedly had become native, remaining in the state even in the summer. The increase was attributed to a lack of natural predators, an abundance of water, and plentiful grass in manicured lawns in urban areas.[22] Canada geese were eliminated in Ohio following the American Civil War, but were reintroduced in 1956 with 10 pairs. The population was estimated at 18,000 in 1979. The geese are considered protected, though a hunting season is allowed from September 1–15, with a daily bag limit of five.[23] The Ohio Department of Natural Resources recommends a number of non-lethal scare and hazing tactics for nuisance geese, but if such methods have been used without success, they may issue a permit which can be used from March 11 through August 31 to destroy nests, conduct a goose roundup or shoot geese.[24]

Outside North America

Eurasia

Canada geese have reached Northern Europe naturally, as has been proved by ringing recoveries. The birds include those of the subspecies B. c. parvipes, and possibly others. These geese are also found naturally on the Kamchatka Peninsula in eastern Siberia, and eastern China.

Canada geese have also been introduced in Europe, and had established populations in Great Britain in the middle of the eighteenth century,[25] Ireland, the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Germany, Scandinavia, and Finland. Most European populations are not migratory, but those in more northerly parts of Sweden and Finland migrate to the North Sea and Baltic coasts.[26] Semitame feral birds are common in parks, and have become a pest in some areas. In the early 17th century, explorer Samuel de Champlain sent several pairs of geese to France as a present for King Louis XIII. The geese were first introduced in Britain in the late 17th century as an addition to King James II's waterfowl collection in St. James's Park. They were introduced in Germany and Scandinavia during the 20th century, starting in Sweden in 1929. In Britain, they were spread by hunters, but remained uncommon until the mid-20th century. Their population grew from 2200 to 4000 birds in 1953 to an estimated 82,000 in 1999, as changing agricultural practices and urban growth provided new habitat. European birds are mostly descended from the subspecies B. c. canadensis, likely with some contributions from the subspecies B. c. maxima.[27]

New Zealand

Canada geese were introduced as a game bird into New Zealand in 1905. They have become a problem in some areas by fouling pastures and damaging crops. They were protected under the Wildlife Act 1953 and the population was managed by Fish and Game New Zealand, which culled excessive bird numbers. In 2011, the government removed the protection status, allowing anyone to kill the birds.[28]

Finland

The Canada goose was first brought to Finland as a game animal in the 1960s. The Canada goose is well adapted to living in Finland and is even causing some problems, particularly on the golf courses and pastures in the country. The problem, though, at the moment, is merely cosmetic.[29]

Behaviour

_cleaning_feathers.jpg)

Like most geese, the Canada goose is naturally migratory with the wintering range being most of the United States. The calls overhead from large groups of Canada geese flying in V-shaped formation signal the transitions into spring and autumn. In some areas, migration routes have changed due to changes in habitat and food sources. In mild climates from south western British Columbia to California to the Great Lakes, some of the population has become nonmigratory due to adequate winter food supply and a lack of former predators.[30]

Males exhibit agonistic behavior both on and off breeding and nesting grounds. This behavior rarely involves interspecific killing. One documented case involved a male defending his nest from a brant goose that wandered into the area; the following attack lasted for one hour until the death of the brant. The cause of death was suffocation or drowning in mud as a direct result of the Canada goose's pecking the head of the brant into the mud. Researchers attributed it to high hormone levels and the brant's inability to leave the nesting area.[31]

Diet

Canada geese are primarily herbivores,[18] although they sometimes eat small insects and fish.[32] Their diet includes green vegetation and grains. The Canada goose eats a variety of grasses when on land. It feeds by grasping a blade of grass with the bill, then tearing it with a jerk of the head. The Canada goose also eats beans and grains such as wheat, rice, and corn when they are available. In the water, it feeds from aquatic plants by sliding its bill at the bottom of the body of water. It also feeds on aquatic plant-like algae, such as seaweeds.[14]

In urban areas, it is also known to pick food out of garbage bins. They are also sometimes hand-fed a variety of grains and other foods by humans in parks. Canada geese prefer lawngrass in urban areas. They usually graze in open areas with wide clearance to avoid potential predators.[33]

Reproduction

During the second year of their lives, Canada geese find a mate. They are monogamous, and most couples stay together all of their lives. If one dies, the other may find a new mate. The female lays from two to nine eggs with an average of five, and both parents protect the nest while the eggs incubate, but the female spends more time at the nest than the male.[14]

Its nest is usually located in an elevated area near water such as streams, lakes, ponds, and sometimes on a beaver lodge. Its eggs are laid in a shallow depression lined with plant material and down.

The incubation period, in which the female incubates while the male remains nearby, lasts for 24–32 days after laying. Canada Geese can respond to external climatic factors by adjusting their laying date to spring maximum temperatures, which may benefit their nesting success.[34]

As the annual summer molt also takes place during the breeding season, the adults lose their flight feathers for 20–40 days, regaining flight about the same time as their goslings start to fly.[35]

As soon as the goslings hatch, they are immediately capable of walking, swimming, and finding their own food (a diet similar to the adult geese). Parents are often seen leading their goslings in a line, usually with one adult at the front, and the other at the back. While protecting their goslings, parents often violently chase away nearby creatures, from small blackbirds to lone humans who approach, after warning them by giving off a hissing sound and then attack with bites and slaps of the wings if the threat does not retreat or has seized a gosling. Canada geese are especially protective animals, and will sometimes attack any animal nearing its territory or offspring, including humans. Most of the species that prey on eggs also take a gosling. Although parents are hostile to unfamiliar geese, they may form groups of a number of goslings and a few adults, called crèches.

The offspring enter the fledgling stage any time from 6 to 9 weeks of age. They do not leave their parents until after the spring migration, when they return to their birthplace.[18]

Migration

Canada geese are known for their seasonal migrations. Most Canada geese have staging or resting areas where they join up with others. Their autumn migration can be seen from September to the beginning of November.[36] The early migrants have a tendency to spend less time at rest stops and go through the migration much faster. The later birds usually spend more time at rest stops. Some geese return to the same nesting ground year after year and lay eggs with their mate, raising them in the same way each year. This is recorded from the many tagged geese which frequent the East Coast.

Canada geese fly in a distinctive V-shaped flight formation, with an altitude of 1 km (3,000 feet) for migration flight. The maximum flight ceiling of Canada geese is unknown, but they have been reported at 9 km (29,000 feet).[37]

Flying in the V formation has been the subject of study by researchers. The front position is rotated since flying in front consumes the most energy. Canada geese leave the winter grounds more quickly than the summer grounds. Elevated thyroid hormones, such as T3 and T4, have been measured in geese just after a big migration. This is believed because of the long days of flying in migration the thyroid gland sends out more T4 which help the body cope with the longer journey. The increased T4 levels are also associated with increased muscle mass (hypertrophy) of the breast muscle, also because of the longer time spent flying. It is believed that the body sends out more T4 to help the goose's body with this long task by speeding up the metabolism and lowering the temperature at which the muscles work.[38] Also, other studies show levels of stress hormones such as corticosterone rise dramatically in these birds during and after a migration.[39]

Survival

The lifespan in the wild of geese that survive to adulthood ranges from 10 to 24 years.[14] The British longevity record is held by a specimen tagged as a nestling, which was observed alive at the University of York at the age of 31.[40][41]

Predators

Known predators of eggs and goslings include coyotes,[42] Arctic foxes (Vulpes lagopus), northern raccoons (Procyon lotor), red foxes (Vulpes vulpes), large gulls (Larus species), common ravens (Corvus corax), American crows (Corvus brachyrhynchos), carrion crows (in Europe, Corvus corone) and both brown (Ursus arctos) and American black bears (Ursus americanus).[18][43][44][45][46]

Once they reach adulthood, due to their large size and often aggressive behavior, Canada geese are rarely preyed on, although prior injury may make them more vulnerable to natural predators.[47] Beyond humans, adults can be taken by coyotes[48] and grey wolves (Canis lupus).[49] Avian predators that are known to kill adults, as well as young geese, include snowy owls (Bubo scandiacus), golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) and bald eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) and, though rarely on large adult geese, great horned owls (Bubo virginianus), goshawks (Accipiter gentilis),[50][51] peregrine falcons (Falco peregrinus), and gyrfalcons (Falco rusticolus).[18][45] Adults are quite vigorous at displacing potential predators from the nest site, with predator prevention usually falling to the larger male of the pair.[52][53][54] Males usually attempt to draw attention of approaching predators and toll (mob terrestrial predators without physical contact) often in accompaniment with males of other goose species. Eagles of both species frequently cause geese to fly off en masse from some distance, though in other instances, geese may seem unconcerned at perched bald eagles nearby, seemingly only reacting if the eagle is displaying active hunting behavior.[55] Canada geese are quite wary of humans where they are regularly hunted and killed, but can otherwise become habituated to fearlessness towards humans, especially where they are fed by them.[56] This often leads to the geese becoming overly aggressive towards humans, and large groups of the birds may be considered a nuisance if they are causing persistent issues to humans and other animals in the surrounding area.

Salinity

Salinity plays a role in the growth and development of goslings. Moderate to high salinity concentrations without fresh water results in slower development, growth, and saline-induced mortality. Goslings are susceptible to saline-induced mortality before their nasal salt glands become functional, with the majority occurring before the sixth day of life.[57]

Disease

Canada geese are susceptible to avian bird flus, such as H5N1. A study carried out using the HPAI virus, a H5N1 virus, found that the geese were susceptible to the virus. This proved useful for monitoring the spread of the virus through the high mortality of infected birds. Prior exposure to other viruses may result in some resistance to H5N1.[58]

Relationship with humans

.jpg)

In North America, nonmigratory Canada goose populations have been on the rise. The species is frequently found on golf courses, parking lots, and urban parks, which would have previously hosted only migratory geese on rare occasions. Owing to its adaptability to human-altered areas, it has become one of the most common waterfowl species in North America. In many areas, nonmigratory Canada geese are now regarded as pests by humans. They are suspected of being a cause of an increase in high fecal coliforms at beaches.[59] An extended hunting season, deploying noise makers, and hazing by dogs have been used in an attempt to disrupt suspect flocks.[60] A goal of conservationists has been to focus hunting on the nonmigratory populations (which tend to be larger and more of a nuisance) as opposed to migratory flocks showing natural behavior, which may be rarer.

Since 1999, the United States Department of Agriculture Wildlife Services agency has been engaged in lethal culls of Canada geese primarily in urban or densely populated areas. The agency responds to municipalities or private land owners, such as golf courses, which find the geese obtrusive or object to their waste.[61] Addling goose eggs and destroying nests are promoted as humane population control methods.[62] Flocks of Canada goose can also be captured during moult and this method of culling is used to control invasive populations.[63]

Canada geese are protected from hunting and capture outside of designated hunting seasons in the United States by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act,[64] and in Canada under the Migratory Birds Convention Act.[65] In both countries, commercial transactions such as buying or trading are mostly prohibited and the possession, hunting, and interfering with the activity of the animals are subject to restrictions.[66][67] In the UK, as with native bird species, the nests and eggs of Canada geese are fully protected by law, except when their removal has been specifically licensed, and shooting is generally permitted only during the defined open season.[68][69][70]

Geese have a tendency to attack humans when they feel themselves or their goslings to be threatened. First, the geese stand erect, spread their wings, and produce a hissing sound. Next, the geese charge. They may then bite or attack with their wings.[71]

Aircraft strikes

Canada geese have been implicated in a number of bird strikes by aircraft. Their large size and tendency to fly in flocks may exacerbate their impact. In the United States, the Canada goose is the second-most damaging bird strike to airplanes, with the most damaging being turkey vultures.[72] Canada geese can cause fatal crashes when they strike an aircraft's engine. The FAA has reported 1,772 known civil aircraft strikes within the United States between 1990–2018.[73] The total cost of these bird strikes to general and commercial aviation has been reported to exceed $130 million.[74]

In 1995, a U.S. Air Force E-3 Sentry aircraft at Elmendorf AFB, Alaska, struck a flock of Canada geese on takeoff, losing power in both port side engines. It crashed 2 mi (3.2 km) from the runway, killing all 24 crew members. The accident sparked efforts to avoid such events, including habitat modification, aversion tactics, herding and relocation, and culling of flocks.[75][76][77] In 2009, a collision with a flock of migratory Canada geese resulted in US Airways Flight 1549 suffering a total power loss after takeoff causing the crew of the aircraft to land the plane on the Hudson River with no loss of human life.[78][79][80]

Cuisine

As a large, common wild bird, the Canada goose is a common target of hunters, especially in its native range. Drake Larsen, a researcher in sustainable agriculture at Iowa State University, described them to Atlantic magazine as "so yummy...good, lean, rich meat. I find they are similar to a good cut of beef."[81] The British Trust for Ornithology, however, has described them as "reputedly amongst the most inedible of birds." The US goose harvest for 2013–14 reported over 1.3 million geese taken.[82] Canada geese are rarely farmed, and sale of wild Canada goose meat is rare due to regulation, and slaughterhouses' lack of experience with wild birds. Geese in New York City parks culled by the New York City Department of Environmental Protection have been donated to food banks in Pennsylvania. As of 2011, the sale of wild Canada goose meat was not permitted in the UK; some landowners have lobbied for this ban to be withdrawn to allow them income from sale of game meat.[83]

Population

In 2000, the North American population for the geese was estimated to be between 4 million and 5 million birds.[84] A 20-year study from 1983 to 2003 in Wichita, Kansas, found the size of the winter Canada goose population within the city limits increase from 1,600 to over 18,000 birds.[84]

References

- BirdLife International. (2016). Branta canadensis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22679935A85972211.en

- Long, John L. (1981). Introduced Birds of the World. Agricultural Protection Board of Western Australia. pp. 21–493.

- Linnaeus, C. (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata (in Latin). Holmia: Laurentius Salvius.

- Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 77, 87. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- Gill, Frank; Minturn, Wright (2006). Birds of the World: Recommended English Names. Christopher Helm.

- Gill, F.; Donsker, D., eds. (2012). "IOC World Bird Names (v. 3.1)". Retrieved May 1, 2012.

- "Canada goose (bird)". Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved March 11, 2013.

- "Canada goose or canadian goose, n.". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (4th ed.). Houghton Mifflin Company. 2000. OCLC 43499541.

- Stackhouse, Mark. "The New Goose".

- Banks, Richard (2007) Review of Harold Hanson's "The White-Cheeked Geese: Branta Canadensis, B. Maxima, B. ‘‘Lawrensis’’, B. Hutchinsii, B. Leucopareia, And B. Minima. Taxonomy, Ecophysiographic Relationships, Biogeography, And Evolutionary Considerations. Volume 1. Eastern Taxa" The Wilson Journal of Ornithology

- "Audubon Society". Archived from the original on July 7, 2010. Retrieved June 5, 2008.

- Ogilvie, Malcolm; Young, Steve (2004). Wildfowl of the World. New Holland Publishers. ISBN 978-1-84330-328-2.

- Madge, Steve; Burn, Hilary (1988). Waterfowl: An Identification Guide to the Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-46727-5.

- Dewey, T.; Lutz, H. (2002). "Branta canadensis". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved November 18, 2007.

- Mowbray, Thomas B., Craig R. Ely, James S. Sedinger and Robert E. Trost. (2002). "Canada Goose (Branta canadensis)", The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- "Canada Goose - Introduction - Birds of North America Online". birdsna.org. 2002. Retrieved March 9, 2020.

- "Canada Goose - Introduction - Birds of North America Online". birdsna.org. 2002. Retrieved March 9, 2020.

- Mowbray, Thomas B.; Ely, Craig R.; Sedinger, James S.; Trost, Robert E. (2002). "Canada Goose (Branta canadensis)". In Poole, A. (ed.). The Birds of North America. Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

- Hanson, Harold C. (1997). The Giant Canada Goose (2nd ed.). Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 978-0-8093-1924-4.

- "Obituary: Forrest Lee". The Bismarck Tribune. Bismarck, North Dakota. February 7, 2013.

- "Why Do Canada Geese Like Urban Areas?". The Humane Society of the United States. Retrieved February 20, 2014.

- "Ohio reports increase in Canada geese population". The Lima News, via Associated Press Dayton. March 9, 2015. Archived from the original on May 18, 2015. Retrieved May 3, 2015.

- Hamrick, Brian (May 4, 2015). "Canadian Geese get violent during nesting, population on the rise". WLWT. Retrieved May 6, 2015.

- "Nuisance Wildlife". Ohio Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved March 13, 2018.

- Attenborough, D. 1998. The Life of Birds. p.299 BBC. ISBN 0563-38792-0

- Svensson, Lars (2009). Birds of Europe (2nd ed.). Princeton University Press. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-0-691-14392-7.

- David, Cabot (2010). Wildfowl. Collins New Naturalist Library 110. HarperCollins UK. ISBN 978-0007405145.

- "Canada geese protection status changed". Beehive. New Zealand Government. March 17, 2011. Retrieved March 24, 2011.

- "Canada geese". Raunua Zoo.

- "Canada and Cackling Geese: Management and Population Control in Southern Canada" (PDF). Government of Canada. 2010. Retrieved February 22, 2019.

- Krauss, David A.; Salame, Issa (2012). "Interspecific Killing of a Branta bernicla (Brant) by a Male Branta canadensis (Canada Goose)". Northeastern Naturalist. Northeastern Naturalist Humboldt Field Research Institute. 19 (4): 701. doi:10.1656/045.019.0415.

- Angus, Wilson. "Identification and range of subspecies within the Canada and Cackling Goose Complex (Branta canadensis & B. hutchinsii)".

- Smith, Arthur E.; Craven, Scott R.; Curtis, Paul D. (September 2000). Managing Canada Geese in Urban Environments (pdf). Cornell Cooperative Extension. ISBN 978-1-57753-255-2. Lay summary.

- Clermont, J.; Réale, D.; Giroux, J. (2018). "Plasticity in laying dates of Canada Geese in response to spring phenology". Ibis. 160 (3): 597–607. doi:10.1111/ibi.12560.

- Johnsgard, Paul A. (2010) [1978]. Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World (revised online ed.). Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. p. 79.

- Canada, Government of Canada, Environment and Climate Change. "Environment and Climate Change Canada – Nature – Frequently Asked Questions – Canada Geese". www.ec.gc.ca. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- "Canada Geese at Blackwater". US Fish & Wildlife Service. Retrieved August 2, 2013.

- John, T. M.; George, J. C. (1978). "Circulatory levels of thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3) in the migratory Canada goose". Physiological Zoology. 51 (4): 361–370. doi:10.1086/physzool.51.4.30160961. JSTOR 30160961.

- Landys, Mėta M.; Wingfield, John C.; Ramenofsky, Marilyn (2004). "Plasma corticosterone increases during migratory restlessness in the captive white-crowned sparrow Zonotrichia leucophrys gambelli" (PDF). Hormones and Behavior. 46 (5): 574–581. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2004.06.006. PMID 15555499.

- "Longevity records for Britain & Ireland in 2013". British Trust for Ornithology. Archived from the original on January 18, 2015. Retrieved January 13, 2015.

- "Summary of all Ringing Recoveries for Canada Goose". British Trust for Ornithology. Retrieved January 13, 2015.

- "Chicago Area Is Home to Growing Numbers of Coyotes". Illinois Department of Natural Resources. Archived from the original on November 24, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- Campbell, R. W., N. K. Dawe, I. McTaggart-Cowan, J. M. Cooper, G. W. Kaiser, and M. C. E. McNall. (1990). The birds of British Columbia, Vol. 1: introduction and loons through waterfowl. R. Br. Columbia Mus. Victoria.

- Hughes, J. R. (2002). Reproductive success and breeding ground banding of Atlantic population of Canada Geese in northern Québec 2001. Unpubl. rep. Atlantic Flyway Council.

- Barry, T. W. (1967). The geese of the Anderson River delta, Northwest Territories. Phd Thesis. Univ. of Alberta, Edmonton.

- Macinnes, C. D. and Misra, R. K. (1972). "Predation on Canada Goose nests at McConnell River, Northwest Territories". J. Wildl. Manage. 36 (2): 414–422. doi:10.2307/3799071. JSTOR 3799071.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Sargeant, A. B. and D. G. Raveling. (1992) "Mortality during the breeding season", pp. 396–422 in Ecology and management of breeding waterfowl. Batt, B. D. J., A. D. Afton, M. G. Anderson, C. D. Ankney, D. H. Johnson, et al. (eds.) Univ. of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis.

- Hanson, W. C. and Eberhardt, L. L. (1971). "The Columbia River Canada Goose Population 1950–1970". Wildlife Monographs. 28 (28): 3–61. JSTOR 3830431.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Raveling, D. G. and H. G. Lumsden. (1977). "Nesting ecology of Canada Geese in the Hudson Bay Lowlands of Ontario: Evolution and population regulation". Fish Wildl. Res. Rep. No. 98. Ontario Min. Nat. Resour.

- Veldkamp R. (2008). [Cormorants Phalacrocorax carbo and other large bird species as prey of goshawks Accipiter gentilis in De Wieden]. De Takkeling 16: 85–91.

- Madsen, J. (1988). Goshawk, Accipiter gentilis, harassing and killing brent geese Branta bernicla. Meddelelse fra Vildtbiologisk Station (Denmark).

- Bent, A. C. (1925). Life histories of North American wild fowl, Pt. 2. U.S. Natl. Mus. Bull. 130.

- Palmer, R. S. (1976). Handbook of North American birds, Vol. 2: Waterfowl. Pt. 1. Yale Univ. Press, New Haven, CT.

- Collias, N. E. and Jahn, L. R. (1959). "Social behavior and breeding success in Canada Geese (Branta canadensis) confined under semi-natural conditions" (PDF). The Auk. 76 (4): 478–509. doi:10.2307/4082315. JSTOR 4082315.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Mcwilliams, S. R., Dunn, J. P. and Raveling, D. G. (1994). "Predator-prey interactions between eagles and Cackling Canada and Ross' geese during winter in California". Wilson Bull. 106 (2): 272–288. JSTOR 4163419.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Bartelt, Gerald A. (1987). "Effects of Disturbance and Hunting on the Behavior of Canada Goose Family Groups in Eastcentral Wisconsin". The Journal of Wildlife Management. 51 (3): 517–522. doi:10.2307/3801261. JSTOR 3801261.

- Stolley, Doris; Bissonette, John; Kadlec, John (1999). "Effects of saline environments on the survival of wild goslings (Branta canadensis)". American Midland Naturalist. 142 (1): 181–190. doi:10.1674/0003-0031(1999)142[0181:EOSEOT]2.0.CO;2.

- Pasick, John; Berhane, Yohannes; Embury-Hyatt, Carissa; Copps, John; Kehler, Helen; Handel, Katherine; Babiuk, Shawn; Hooper-McGrevy, Kathleen; Li, Yan; Le, Quynh; Phuong, Song (2007). "Susceptibility of Canada geese (Branta canadensis) to highly pathogenic avian influenza virus (H5N1)". Emerging Infectious Diseases. US National Center for Infectious Diseases. 13 (12): 1821–7. doi:10.3201/eid1312.070502. PMC 2876756. PMID 18258030.

- State Parks Again Offering Early Canada Goose Hunting. Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (August 26, 2011)

- Woodruff, Roger A.; Green, Jeffrey S. (1995). "Livestock Herding Dogs: A Unique Application for Wildlife Damage Management". Great Plains Wildlife Damage Control Workshop Proceedings. 12: 43–45.

- Board of Park Commissioners (Seattle) Meeting Minutes Archived February 26, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. July 12, 2001

- MacDonald, Gregg (May 6, 2008). "Goose egg addling stirs concern in Reston". Fairfax County Times. Archived from the original on June 20, 2009. Retrieved June 10, 2009.

- Reyns, Nikolaas; Casaer, Jim; Smet, Lieven De; Devos, Koen; Huysentruyt, Frank; Robertson, Peter A.; Verbeke, Tom; Adriaens, Tim (January 29, 2018). "Cost-benefit analysis for invasive species control: the case of greater Canada goose Branta canadensis in Flanders (northern Belgium)". PeerJ. 6: e4283. doi:10.7717/peerj.4283. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 5793711. PMID 29404211.

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (January 5, 2016). "Migratory Bird Treaty Act Protected Species (10.13 List)". fws.gov.

- Frequently Asked Questions – Canada Geese Archived October 6, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Canadian Wildlife Service

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (April 11, 2012). "Final Environmental Impact Statement: Resident Canada Goose Management – Division of Migratory Bird Management". fws.gov.

- Pynn, Larry (April 5, 2014). "Bird strikes plummet at Vancouver airport". Vancouver Sun.

- "Wild birds and the law" (PDF). RSPB. Retrieved February 1, 2015.

- "Managing Geese on Agricultural Land" (PDF). Scottish government.

- "Environmental management: bird licences". UK Government. Retrieved February 1, 2015.

- Goose Attacks Archived January 1, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Division of Wildlife (Ohio)

- "Bird Plus Plane Equals Snarge". Wired. September 2005. Archived from the original on October 19, 2007.

- "Center for Wildlife and Aviation - Strike Reporting by Year". wildlifecenter.pr.erau.edu. Retrieved February 26, 2019.

- "Wildlife Strikes to Civil Aircraft in the United States, 1990–2017" (PDF).

- "CVR transcript Boeing E-3 USAF Yukla 27 – 22 SEP 1995". Accident investigation. Aviation Safety Network. September 22, 1995. Retrieved January 16, 2009.

- "1995 AWACS crash". CNN. September 23, 1995. Archived from the original on June 28, 2011. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- Barela, Timothy P. (September 22, 1995) Fowl Play. U.S. Air Force News

- Barrett, Barbara (June 8, 2009). "DNA shows jet that landed in Hudson struck migrating geese". McClatchy Newspapers. Archived from the original on June 15, 2009. Retrieved June 8, 2009.

- Maynard, Micheline (January 15, 2009). "Bird Hazard Is Persistent for Planes". The New York Times. Retrieved February 23, 2010.

- "Third Update on Investigation into Ditching of US Airways Jetliner into Hudson River" (Press release). NTSB. February 4, 2009. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- Elton, Sarah (October 19, 2011). "My First Helping of Canada Goose". Atlantic magazine.

- Raftovich, R.V., Chandler, S. C. and Wilkins, K.A. (2015). Migratory bird hunting activity and harvest during the 2013–14 and 2014–15 hunting seasons. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Laurel, Maryland, USA

- Carlson, Kathryn (June 18, 2011). "New York solves its Canada Goose problem by feeding them to Pennsylvania's poor". National Post.

- Maccarone, Alan D.; Cope, Charles (2004). "Recent trends in the winter population of Canada geese (Branta canadensis) in Wichita, Kansas: 1998–2003". Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science. Kansas Academy of Science. 107 (1, 2): 77–82. doi:10.1660/0022-8443(2004)107[0077:RTITWP]2.0.CO;2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Canada Goose. |

- Images and videos of the Canada goose on ARKive

- RSPB Birds by Name: Canada goose

- Canada Goose Species Account – Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- "Canada goose media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Canada Goose – BTO BirdFacts

- Rediscovery report on Giant Canada Goose from 1963 (PDF)