Betula papyrifera

Betula papyrifera (paper birch,[3] also known as (American) white birch[3] and canoe birch[3]) is a short-lived species of birch native to northern North America. Paper birch is named for the tree's thin white bark, which often peels in paper like layers from the trunk. Paper birch is often one of the first species to colonize a burned area within the northern latitudes, and is an important species for moose browsing. The wood is often used for pulpwood and firewood.

| Betula papyrifera | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Paper birch forest in Maine | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Fagales |

| Family: | Betulaceae |

| Genus: | Betula |

| Subgenus: | Betula subg. Betula |

| Species: | B. papyrifera |

| Binomial name | |

| Betula papyrifera | |

| |

| Natural range | |

| Synonyms[1][2] | |

| |

Description

It is a medium-sized deciduous tree typically reaching 20 m (66 feet) tall,[2] and exceptionally to 40 m (130 feet) with a trunk up to 75 cm (30 inches) in diameter.[4] Within forests, it often grows with a single trunk but when grown as a landscape tree it may develop multiple trunks or branch close to the ground.[5]

Paper birch is a typically short-lived species. It handles heat and humidity poorly and may live only 30 years in zones six and up, while trees in colder-climate regions can grow for more than 100 years.[4] B. papyrifera will grow in many soil types, from steep rocky outcrops to flat muskegs of the boreal forest. Best growth occurs in deeper, well drained to dry soils, depending on the location.[6]

- In older trees, the bark is white, commonly brightly so, flaking in fine horizontal strips to reveal a pinkish or salmon-colored inner bark.[5] It often has small black marks and scars. In individuals younger than five years, the bark appears a brown red color[2] with white lenticels, making the tree much harder to distinguish from other birches. The bark is highly weather-resistant. It has a high oil content and this gives it its waterproof and weather-resistant characteristics.[2] Often, the wood of a downed paper birch will rot away, leaving the hollow bark intact.[7]

- The leaves are dark green and smooth on the upper surface; the lower surface is often pubescent on the veins. They are alternately arranged on the stem, oval to triangular in shape, 5–10 cm (2–4 inches) long and about 2⁄3 as wide. The leaf is rounded at the base and tapering to an acutely pointed tip. The leaves have a doubly serrated margin with relatively sharp teeth.[2] Each leaf has a petiole about 2.5 cm (0.98 inches) long that connects it to the stems.

- The fall color is a bright yellow color that contributes to the bright colors within the northern deciduous forest.

- The leaf buds are conical and small and green-colored with brown edges.

- The stems are a reddish-brown color and may be somewhat hairy when young.[5]

- The flowers are wind-pollinated catkins; the female flowers are greenish and 3.8 cm (1.5 inches) long growing from the tips of twigs. The male (staminate) flowers are 5–10 cm (2–4 inches) long and a brownish color. The tree flowers from mid-April to June depending on location. Paper birch is monoecious, meaning that one plant has both male and female flowers.[8]

- The fruit matures in the fall. The mature fruit is composed of numerous tiny winged seeds packed between the catkin bracts. They drop between September and spring. At 15 years of age, the tree will start producing seeds but will be in peak seed production between 40 and 70 years.[6] The seed production is irregular, with a heavy seed crop produced typically every other year and with at least some seeds being produced every year.[6] In average seed years, 2,500,000 seeds per hectare (1,000,000 per acre) are produced, but in bumper years 86,000,000 per hectare (35,000,000 per acre) may be produced. The seeds are light and blow in the wind to new areas; they also may blow along the surface of snow.

- The roots are generally shallow and occupy the upper 60 cm (24 inches) of the soil and do not form taproots. High winds are more likely to break the trunk than to uproot the tree.[6]

Genetics and taxonomy

B. papyrifera hybridizes with other species within the genus Betula.

Several varieties are recognized:[6]

- B. p. var papyrifera the typical paper birch

- B. p. var cordifolia the eastern paper birch (now a separate species); see Betula cordifolia

- B. p. var kenaica Alaskan paper birch (also treated as a separate species by some authors); see Betula kenaica

- B. p. var subcordata Northwestern paper birch

- B. p. var. neoalaskana Alaska paper birch (although this is often treated as a separate species); see Betula neoalaskana

Distribution

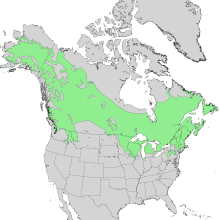

Betula papyrifera is mostly confined to Canada and the far northern United States. It is found in interior (var. humilus) and south-central (var. kenaica) Alaska and in all provinces and territories of Canada, except Nunavut, as well as the far northern continental United States. Isolated patches are found as far south as the Hudson Valley of New York and Pennsylvania, as well as Washington, D.C. High elevation stands are also in mountains to North Carolina, New Mexico, and Colorado. The most southerly stand in the Western United States is located in Long Canyon in the City of Boulder Open Space and Mountain Parks. This is an isolated Pleistocene relict that most likely reflects the southern reach of boreal vegetation into the area during the last Ice Age.[9]

Ecology

In Alaska, paper birch often naturally grows in pure stands by itself or with black or white spruce. In the eastern and central regions of its range, it is often associated with red spruce and balsam fir.[6] It may also be associated with big-toothed aspen, yellow birch, Betula populifolia, and maples.

Shrubs often associated with paper birch in the eastern part of its range include beaked hazel (Corylus cornuta), common bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi), dwarf bush-honeysuckle (Diervilla lonicera), wintergreen (Gaultheria procumbens), wild sarsaparilla (Aralia nudicaulis), blueberries (Vaccinium spp.), raspberries and blackberries (Rubus spp.), elderberry (Sambucus spp.), and hobblebush (Viburnum alnifolium).

Successional relationships

Betula papyrifera is a pioneer species, meaning it is often one of the first trees to grow in an area after other trees are removed by some sort of disturbance. Typical disturbances colonized by paper birch are wildfire, avalanche, or windthrow areas where the wind has blown down all trees. When it grows in these pioneer, or early successional, woodlands, it often forms stands of trees where it is the only species.[4]

Paper birch is considered well adapted to fires because it recovers quickly by means of reseeding the area or regrowth from the burned tree. The lightweight seeds are easily carried by the wind to burned areas, where they quickly germinate and grow into new trees. Paper birch is adapted to ecosystems where fires occur every 50 to 150 years[4] For example, it is frequently an early invader after fire in black spruce boreal forests.[10] As paper birch is a pioneer species, finding it within mature or climax forests is rare because it will be overcome by trees that are more shade-tolerant as secondary succession progresses.

For example, in Alaskan boreal forests, a paper birch stand 20 years after a fire may have 3,000–6,000 trees per acre (7,400–14,800/ha), but after 60 to 90 years, the number of trees will decrease to 500–800 trees per acre (1,200–2,000/ha) as spruce replaces the birch.[4] After approximately 75 years, the birch will start dying and by 125 years, most paper birch will have disappeared unless another fire burns the area.

Paper birch trees themselves have varied reactions to wildfire. A group, or stand, of paper birch is not particularly flammable. The canopy often has a high moisture content and the understory is often lush green.[4] As such, conifer crown fires often stop once they reach a stand of paper birch or become slower-moving ground fires. Since these stands are fire-resistant, they may become seed trees to reseed the area around them that was burned. However, in dry periods, paper birch is flammable and will burn rapidly.[4] As the bark is flammable, it often will burn and may girdle the tree.

Wildlife

Birch bark is a winter staple food for moose. The nutritional quality is poor because of the large quantities of lignin, which make digestion difficult, but is important to wintering moose because of its sheer abundance.[4] Moose prefer paper birch over aspen, alder, and balsam poplar, but they prefer willow (Salix spp.) over birch and the other species listed. Although moose consume large amounts of paper birch in the winter, if they were to eat only paper birch, they may die.[4]

Although white-tailed deer consider birch a "secondary-choice food," it is an important dietary component. In Minnesota, white-tailed deer eat considerable amounts of paper birch leaves in the fall. Snowshoe hares browse paper birch seedlings,[4] and grouse eat the buds. Porcupines and beavers feed on the inner bark.[11] The seeds of paper birch are an important part of the diet of many birds and small mammals, including chickadees, redpolls, voles, and ruffed grouse. Yellow bellied sapsuckers drill holes in the bark of paper birch to get at the sap; this is one of their favorite trees for feeding on.[4]

Conservation

The species is considered vulnerable in Indiana, imperiled in Illinois, Virginia, West Virginia, and Wyoming, and critically imperiled in Colorado and Tennessee.

Uses

Betula papyrifera has a moderately heavy white wood. It makes excellent high-yielding firewood if seasoned properly. The dried wood has a density of 37.4 lb/cu ft (0.599 g/cm3) and an energy density 20,300,000 BTU/cord (5,900,000 kJ/m3).[12] Although paper birch does not have a very high overall economic value, it is used in furniture, flooring, popsicle sticks,[13] pulpwood (for paper), plywood, and oriented strand board.[4] The wood can also be made into spears, bows, arrows, snowshoes, sleds, and other items.[4] When used as pulp for paper, the stems and other nontrunk wood are lower in quantity and quality of fibers, and consequently the fibers have less mechanical strength; nonetheless, this wood is still suitable for use in paper.

The sap is boiled down to produce birch syrup. The raw sap contains 0.9% carbohydrates (glucose, fructose, sucrose)[6] as compared to 2 percent to 3 percent within sugar maple sap. The sap flows later in the season than maples. Currently, only a few small-scale operations in Alaska and Yukon produce birch syrup from this species.[6]

Bark

Its bark is an excellent fire starter; it ignites at high temperatures even when wet. The bark has an energy density of 5,740 cal/g (24,000 J/g) and 3,209 cal/cm3 (220,000 J/cu in), the highest per unit weight of 24 species tested.[6]

Panels of bark can be fitted or sewn together to make cartons and boxes. (A birchbark box is called a wiigwaasi-makak in the Anishinaabe language.) The bark is also used to create a durable waterproof layer in the construction of sod-roofed houses.[7] Many indigenous groups (i.e., Wabanaki peoples) use birchbark for making various items, such as canoes, containers, and wigwams. It is also used as a backing for porcupine quillwork and moosehair embroidery. Thin sheets can be employed as a medium for the art of birchbark biting.

Plantings

Paper birch is planted to reclaim old mines and other disturbed sites, often bare-root or small saplings are planted when this is the goal.[4] Since paper birch is an adaptable pioneer species, it is a prime candidate for reforesting drastically disturbed areas.

When used in landscape planting, it should not be planted near black walnut, as the chemical juglone, exuded from the roots of black walnut, is very toxic to paper birch.

Paper birch is frequently planted as an ornamental because of its graceful form and attractive bark. The bark changes to the white color at about 3 years of growth.[5] Paper birch grows best in USDA zones 2–6,[5] due to its intolerance of high temperatures. Betula nigra, or river birch, is recommended for warm-climate areas warmer than zone 6, where paper birch is rarely successful.[14] B. papyrifera is more resistant to the bronze birch borer than Betula pendula, which is similarly planted as a landscape tree.

Pests

Birch skeletonizer is a small larva that feeds on the leaves and causes browning.[14]

Birch leafminer is a common pest that feeds from the inside of the leaf and causes the leaf to turn brown. The first generation appears in May but there will be several generations per year. Severe infestations may stress the tree and make it more vulnerable to the bronze birch borer.[14]

When a tree is stressed, bronze birch borers may kill the tree. The insect bores into the sapwood, beginning at the top of the tree and causing death of the tree crown.[14] The insect has a D-shaped emergence hole where it chews out of the tree. Healthy trees are resistant to the borer, but when grown in sub-ideal conditions, the defense mechanisms of the tree may not function properly. Chemical controls exist.

In culture

It is the provincial tree of Saskatchewan and the state tree of New Hampshire.[15][16]

People sometimes vandalize the bark of this tree by carving into it with a knife or by peeling off layers of the bark. Both forms of vandalism can cause unsightly scars on the tree.

References

- "Betula papyrifera". World Checklist of Selected Plant Families (WCSP). Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 2012-10-10 – via The Plant List.

- Furlow, John J. (1997). "Betula papyrifera". In Flora of North America Editorial Committee (ed.). Flora of North America North of Mexico (FNA). 3. New York and Oxford – via eFloras.org, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA.

- "Betula papyrifera". Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN). Agricultural Research Service (ARS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- Uchytil, Ronald J. (1991). "Betula papyrifera". Fire Effects Information System (FEIS). US Department of Agriculture (USDA), Forest Service (USFS), Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory. Retrieved 5 July 2016 – via https://www.feis-crs.org/feis/.

- Dirr, Michael A (1990). Manual of woody landscape plants (4. ed., rev. ed.). Champaign, Illinois: Stipes Publishing Company. ISBN 0-87563-344-7.

- Burns, Russell M; Honkala, Barbara H. (1990). Sylvics of North America: Hardwoods. Washington: U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Forest Service u.a. ISBN 0-16-029260-3. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- Ewing, Susan (April 1, 1996). The Great Alaska Nature Factbook. Portland, Oregon: Alaska Northwest Books. ISBN 978-0-88240-454-7.

- Rhoads, Ann; Block, Timothy. The Plants of Pennsylvania (2 ed.). Philadelphia Pa: University of Pennsylvania press. ISBN 978-0-8122-4003-0.

- Cooper, David J. (Spring 1984). "Ecological Survey of the City of Boulder, Colorado Mountain Parks" (PDF). City of Boulder Parks and Recreation Department: 16. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-05. Retrieved 2011-09-16. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Hogan, C. Michael (2008). "Black Spruce (Picea mariana)". GlobalTwitcher. Archived from the original on 2011-10-05. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- Peattie, Donald Culross (1953). A Natural History of Western Trees. New York: Bonanza Books. p. 385.

- "Wood – Combustion Heat Values". www.engineeringtoolbox.com. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- Bellis, Mary. "Popsicle – The History of the Popsicle". About.com. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- "Betula papyrifera - Paper Birch" (PDF). Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- "Saskatchewan's Provincial Tree".

- "Fast New Hampshire Facts". NH.gov. Retrieved August 28, 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Paper Birch. |