Politics of Quebec

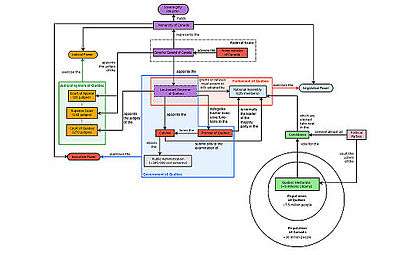

The politics of Quebec are centred on a provincial government resembling that of the other Canadian provinces, namely a constitutional monarchy and parliamentary democracy. The capital of Quebec is Quebec City, where the Lieutenant Governor, Premier, the legislature, and cabinet reside.

The unicameral legislature — the National Assembly of Quebec — has 125 members. Government is conducted based on the Westminster model.

Political system

The British-type parliamentarism based on the Westminster system was introduced in the Province of Lower Canada in 1791. The diagram at right represents the political system of Québec since the 1968 reform. Prior to this reform, the Parliament of Québec was bicameral.

Lieutenant Governor

- asks the leader of the majority party to form a government in which he will serve as Premier

- enacts the laws adopted by the National Assembly

- has the power to veto.

Premier

- appoints the members of the Cabinet and the heads of public corporations

- determines the date of the coming general elections

Members of the National Assembly (MNAs)

- are elected using the first-past-the-post voting system

- there are 125 Members of the National Assembly, so approximately one MNA for each 45,000 electors.

Institutions

Many of Quebec's political institutions are among the oldest in North America. The first part of this article presents the main political institutions of Quebec society. The last part presents Québec's current politics and issues.

Parliament of Quebec

The Parliament of Québec holds the legislative power. It consists of the National Assembly of Québec and the Lieutenant Governor of Quebec.

National Assembly of Quebec

The National Assembly is part of a legislature based on the Westminster System. However, it has a few special characteristics, one of the most important being that it functions primarily in French, although French and English are Constitutionally official and the Assembly's records are published in both languages. The representatives of the Québec people are elected with the first-past-the-post electoral method.

The government is constituted by the majority party and it is responsible to the National Assembly. Since the abolition of the Legislative Council at the end of 1968, the National Assembly has all the powers to enact laws in the provincial jurisdiction as specified in the Constitution of Canada.

Government of Quebec

The government of Quebec consists of all the ministries and governmental branches that do not have the status of independent institutions, such as municipalities and regional county municipalities.

Executive Council

The Executive Council is the body responsible for decision-making in the government. It is composed of the Lieutenant Governor (known as the Governor-in-Council), the Premier (in French Premier minister), the government ministers, the ministers of state and delegate ministers. The Executive Council directs the government and the civil service, and oversees the enforcement of laws, regulations and policies. Together with the Lieutenant Governor, it constitutes the government of Québec. See also Premier of Québec.

Quebec Ombudsman

The Quebec Ombudsman is a legislative officer responsible for handling complaints from individuals, companies and associations who believe the government of Quebec or any of its branches has made an error or treated them unjustly. The Ombudsman has certain powers defined by the Public Protector Act. The Québec Ombudsman has a social contract with Québécois to ensure the transparency of the state.

Human Rights and Youth Rights Commission

The Commission des droits de la personne et des droits de la jeunesse (Human Rights and Youth Rights Commission) is a publicly funded agency created by the Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms. Its members are appointed by the National Assembly. The commission has been given powers to promote and protect human rights within all sectors of Québec society. Government institutions and Parliament are bound by the provisions of the Charter. The commission may investigate into possible cases of discrimination, whether by the State or by private parties. It may introduce litigation if its recommendations were not followed.

Québec Office of the French language

The Office Québécois de la Langue Française (Quebec Office of the French language) is an organization created in 1961. Its mandate was greatly expanded by the 1977 Charter of the French Language. It is responsible for applying and defining Québec's language policy pertaining to linguistic officialization, terminology and francization of public administration and businesses.

See language policies for a comparison with other jurisdictions in the world.

Council on the Status of Women

Established in 1963, the Conseil du statut de la femme (Council on the Status of Women) is a government advisory and study council responsible for informing the government of the status of women's rights in Québec. The council is made of a chair and 10 members appointed by the Québec government every four to five years. The head office of the council is in Québec City and it has 11 regional offices throughout Québec.

Quebec Commission on Access to Information

A first in North America, the Commission d'accès à l'information du Québec (Quebec Commission on Access to Information, CAI) is an institution created in 1982 to administer the Quebec legislative framework of access to information and protection of privacy.

The first law related to privacy protection is the Consumer Protection Act, enacted in 1971. It ensured that all persons had the right to access their credit record. A little later, the Professional Code enshrined principles such as professional secrecy and the confidential nature of personal information.

Today, the CAI administers the law framework of the Act respecting access to documents held by public bodies and the protection of personal information as well as the Act respecting the protection of personal information in the private sector.

Chief electoral officer of Québec

Independent from the government, this institution is responsible for the administration of the Québec electoral system.

Judicial bodies

The principal judicial courts of Québec are the Court of Quebec, the Superior Court and the Court of Appeal. The judges of the first are appointed by the Government of Quebec, while the judges of the two others are appointed by the Government of Canada.

In 1973, the Tribunal des professions was created to behave as an appeal tribunal to decisions taken by the various discipline committees of Quebec's professional orders. The current president is Paule Lafontaine.

On December 10, 1990, the Human Rights Tribunal of Quebec was created. It became the first judicial tribunal in Canada specializing in human rights. The current president is Michèle Rivet.

An administrative tribunal, the Tribunal administratif du Québec is in operation since April 1, 1998, to resolve disputes between citizens and the government. The current president is Jacques Forgues.

Municipal and regional institutions

The territory of Quebec is divided into 17 administrative regions: Bas-Saint-Laurent, Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean, Capitale-Nationale, Mauricie, Estrie, Montreal, Outaouais, Abitibi-Témiscamingue, Côte-Nord, Nord-du-Québec, Gaspésie-Îles-de-la-Madeleine, Chaudière-Appalaches, Laval, Lanaudière, Laurentides, Montérégie, and Centre-du-Québec.

Inside the regions, there are municipalities and regional county municipalities (RCMs).

School boards

On July 1, 1998, 69 linguistic school boards, 60 Francophone and 9 Anglophone, were created in replacement for the former 153 Catholic and Protestant boards. In order to pass this law, which ended a debate of over 30 years, it was necessary for the Parliament of Canada to amend Article 93 of the Constitution Act 1867.

Sharia Law Ban

Sharia law is explicitly banned in Quebec, upheld by a unanimous vote against it in 2005 by the National Assembly.[1]

Political history

When Quebec became one of the four founding provinces of the Canadian Confederation, guarantees for the maintenance of its language and religion under the Quebec Act of 1774 formed part of the British North America Act, 1867. English and French were made the official languages in Quebec Courts and the provincial legislature. The Quebec school system was provided public funding for a dual system based on the Roman Catholic and Protestant religions. Under the Constitution Act, 1867 the provinces were granted control of education. The religious-based separate school systems continued in Quebec until the 1990s when the Parti Québécois government of Lucien Bouchard requested an amendment under provisions of the Constitution Act, 1982 to formally secularize the school system along linguistic lines.

19th century

| Government | Conservative | Liberal | Conservative | Liberal | Conservative | Liberal | ||||

| Party | 1867 | 1871 | 1875 | 1878 | 1881 | 1886 | 1890 | 1892 | 1897 | 1900 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative | 51 | 46 | 43 | 32 | 49 | 26 | 23 | 51 | 23 | 7 |

| Liberal | 12 | 19 | 19 | 31 | 15 | 33 | 43 | 21 | 51 | 67 |

| Independent Conservative | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Independent Liberal | 1 | |||||||||

| Parti national | 3 | 5 | ||||||||

| Parti ouvrier | 1 | |||||||||

| Vacant | 1 | |||||||||

| Total | 65 | 65 | 65 | 65 | 65 | 65 | 73 | 73 | 74 | 74 |

Early 20th century or Liberal Era

| Government | Liberal | ||||||||

| Party | 1904 | 1908 | 1912 | 1916 | 1919 | 1923 | 1927 | 1931 | 1935 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liberal | 67 | 57 | 63 | 75 | 74 | 64 | 74 | 79 | 47 |

| Conservative | 7 | 14 | 16 | 6 | 5 | 20 | 9 | 11 | 17 |

| Action libérale nationale | 25 | ||||||||

| Ligue nationaliste | 3 | 1 | |||||||

| Independent Liberal | 1 | ||||||||

| Parti ouvrier | 2 | ||||||||

| Other | 1 | 2 | |||||||

| Total | 74 | 74 | 81 | 81 | 81 | 85 | 85 | 90 | 89 |

La grande noirceur, the Quiet Revolution and Pre-National Assembly

| Government | UN | Liberal | UN | Liberal | UN | Liberal | |||||

| Party | 1936 | 1939 | 1944 | 1948 | 1952 | 1956 | 1960 | 1962 | 1966 | 1970 | 1973 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Union Nationale | 76 | 15 | 48 | 82 | 68 | 72 | 43 | 31 | 56 | 17 | |

| Liberal | 14 | 70 | 37 | 8 | 23 | 20 | 51 | 63 | 50 | 72 | 102 |

| Bloc Populaire | 4 | ||||||||||

| Parti social démocratique | 1 | ||||||||||

| Ralliement creditiste | 12 | 2 | |||||||||

| Parti Québécois | 7 | 6 | |||||||||

| Other | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||

| Total | 90 | 86 | 91 | 91 | 92 | 93 | 95 | 95 | 108 | 108 | 110 |

Duplessis years 1936–1959

Premier Maurice Duplessis and his Union Nationale party emerged from the ashes of the Conservative Party of Quebec and the Paul Gouin's Action libérale nationale in the 1930s. This political lineage dates back to the 1850s Parti bleu of Louis-Hippolyte Lafontaine, a center-right party in Quebec that emphasized provincial autonomy and allied itself with Conservatives in English Canada. Under his government, the Roman Catholic and Protestant Churches maintained the control they previously gained over social services such as schools and hospitals. The authoritarian Duplessis used the provincial police and the "Padlock Law" to suppress unionism and gave the Montreal-based Anglo-Scot business elite, as well as British and American capital a free rein in running the Quebec economy. His government also continued to attempt to prevent circulation of books banned by the Catholic Church, combated communism and even tried to shut down other Christian religions like the Jehovah's Witnesses who evangelized in French Canada.[2][3][4] The clergy used its influence to exhort Catholic voters to continue electing with the Union Nationale and threaten to excommunicate sympathisers of liberal ideas. For the time it lasted, the Duplessis regime resisted the North American and European trend of massive State investment in education, health, and social programs, turning away federal transfers of funds earmarked for these fields; he jealously guarded provincial jurisdictions. Common parlance speaks of these years as "La Grande Noirceur" The Great Darkness, as in the first scenes of the film Maurice Richard.

Quiet Revolution 1960–1966

In 1960, under a new Liberal Party government led by Premier Jean Lesage, the political power of the church was greatly reduced. Quebec entered an accelerated decade of changes known as the Quiet Revolution. Liberal governments of the 1960s followed a robust nationalist policy of "maîtres chez nous" ("masters in our own home") that would see French-speaking Quebecers use the state to elevate their economic status and assert their cultural identity. The government took control of the education system, nationalized power production and distribution into Hydro-Québec (the provincial power utility), unionized the civil service, founded the Caisse de Depot to manage the massive new government pension program, and invested in companies that promoted French Canadians to management positions in industry. In 1966, the Union Nationale returned to power despite losing the popular vote by nearly seven points to the Liberal Party, but could not turn the tide of modernization and secularization that the Quiet Revolution had started. Both Liberal and Union Nationale governments continued to oppose federal intrusion into provincial jurisdiction.

Post-National Assembly, Rise of Quebec nationalist movements and Recent political history

| Government | PQ | Liberal | PQ | Liberal | PQ | Liberal | CAQ | |||||

| Party | 1976 | 1981 | 1985 | 1989 | 1994 | 1998 | 2003 | 2007 | 2008 | 2012 | 2014 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coalition Avenir Québec | 19 | 22 | 74 | |||||||||

| Liberal | 26 | 42 | 99 | 92 | 47 | 48 | 76 | 48 | 66 | 50 | 70 | 32 |

| Parti Québécois | 71 | 80 | 23 | 29 | 77 | 76 | 45 | 36 | 51 | 54 | 30 | 10 |

| Québec solidaire | 1 | 2 | 3 | 10 | ||||||||

| Union Nationale | 11 | |||||||||||

| Action démocratique du Québec | 1 | 1 | 4 | 41 | 7 | |||||||

| Ralliement creditiste | 1 | |||||||||||

| Parti national populaire | 1 | |||||||||||

| Equality | 4 | |||||||||||

| Total | 110 | 122 | 122 | 125 | 125 | 125 | 125 | 125 | 125 | 125 | 125 | 125 |

René Lévesque and "Sovereignty-Association"

A non-violent Quebec independence movement slowly took form in the late 1960s. The Parti Québécois was created by the sovereignty-association movement of René Lévesque; it advocated recognizing Quebec as an equal and independent (or "sovereign") nation that would form an economic "association" with the rest of Canada. An architect of the Quiet Revolution, Lévesque was frustrated by federal-provincial bickering over what he saw as increasing federal government intrusions into provincial jurisdictions. He saw a formal break with Canada as a way out of this. He broke with the provincial Liberals who remained committed to the policy of defending provincial autonomy inside Canada.[5]

Pierre Trudeau's liberalism

In reaction to events in Quebec and formal demands of the Lesage government, Lester Pearson's ruling Liberal government in Ottawa sought to address the new political assertiveness of Quebec. He commissioned the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism in 1963. Pearson also recruited Pierre Trudeau, who campaigned against the violation of civil liberties under Duplessis and the economic and political marginalization of French Quebecers in the 1950s. Trudeau saw official bilingualism in Canada as the best way of remedying this.

In 1968, Trudeau was elected Prime Minister on a wave of "Trudeaumania". In 1969, his government instituted Official Bilingualism with the Official Languages Act which made French and English official languages and guaranteed linguistic minorities (English-speaking in Quebec, French-speaking elsewhere) the right to federal services in their language of choice, where the number justifies federal spending. He also implemented the policy of multiculturalism, answering the concern of immigrant communities that their cultural identities were being ignored. In 1971, Trudeau also failed in an attempt to bring home the Canadian Constitution from Great Britain at the Victoria conference when Robert Bourassa refused to accept a deal that would not include a Constitutional veto on federal institutions for Quebec.

Trudeau's vision was to create a Constitution for a "Just Society" with a strong federal government founded on shared values of individual rights, bilingualism, social democratic ideals, and, later on, multiculturalism. As Liberal Justice Minister in 1967, he eliminated Canada's sodomy law stating "The state has no business in the bedrooms of the nation"; he also created the first Divorce Act of Canada. This government also repealed Canada's race-based immigration law.

FLQ and the October Crisis

During the 1960s, a violent terrorist group known as the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ) was formed in an effort to attain Quebec independence. In October 1970, their activities culminated in events referred to as the October Crisis when the British Trade commissioner James Cross was kidnapped along with Pierre Laporte, a provincial minister and Vice-Premier, who was killed a few days later. Quebec Premier Robert Bourassa called for military assistance to guard government officials. Prime Minister Trudeau responded by declaring the War Measures Act to stop what was described as an "Apprehended Insurrection" by the FLQ. Critics charge that Trudeau violated civil liberties by arresting thousands of political activists without a warrant as allowed by the Act. Supporters of these measures point to their popularity at the time and the fact that the FLQ was wiped out. Independence-minded Quebecers would now opt for the social democratic nationalism of the Parti Québécois.

Sovereigntists elected and the Anglophone exodus

Broad-based dissatisfaction by both English and French-speaking Quebecers with the government of Robert Bourassa saw Parti Québécois led by René Lévesque win the Quebec provincial election in 1976. The first PQ government was known as the "republic of professors", for its high number of candidates teaching at the university level. The PQ government passed laws limiting financing of political parties and the Charter of the French Language (Bill 101). The Charter established French as the sole official language of Quebec. The government claimed the Charter was needed to preserve the French language in an overwhelmingly anglophone North American continent.

The enactment of Bill 101 was highly controversial and led to an immediate and sustained exodus of anglophones from Quebec that, according to Statistics Canada (2003), since 1971 saw a drop of 599,000 of those Quebecers whose mother tongue was English.[6] This exodus of English speakers provided a substantial and permanent boost to the population of the city of Toronto, Ontario.[7] This Quebec diaspora occurred for a number of reasons including regulations that made French the only language of communication allowed between employers and their employees. Under pain of financial penalties, all businesses in Quebec having more than fifty employees were required to obtain a certificate of francization [Reg.139-140] and those businesses with over one hundred employees were obliged to establish a Committee of francization [Reg.136][8] As well, the language law placed restrictions on school enrollment for children based on parental language of education and banned outdoor commercial signs displaying languages other than French. The section of the law regarding language on signs was deemed unconstitutional by the Supreme Court of Canada under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, see: Ford v Quebec (AG). The revised law of 1988 adheres to the Supreme Court judgment, specifying that signs can be multilingual so long as French is predominant. The maintenance of an inspectorate to enforce the sign laws remains controversial. However, most Quebeckers adhere to the sign laws, as remembrance of what Montreal looked like (an English city for a French majority) before the sign laws is still vivid.

1980 referendum and the Constitution Act of 1982

In the 1980 Quebec referendum, Premier René Lévesque asked the Quebec people for "a mandate to negotiate" his proposal for "sovereignty-association" with the federal government. The Referendum promised that a subsequent deal would be ratified with a second referendum. Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau would campaign against it, promising a renewed federalism based on a new Canadian Constitution. Sixty per cent of the Quebec electorate voted against the sovereignty-association project. After opening a final round of constitutional talks, the Trudeau government patriated the constitution in 1982 without the approval of the Quebec government, which sought to retain a veto on constitutional amendments along with other special legal recognition within Canada. The new constitution featured a modern Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms] based on individual freedoms that would ban racial, sexual, and linguistic discrimination and enshrine minority language rights (English in Quebec, French elsewhere in Canada). After dominating Quebec politics for more than a decade, both Lévesque and Trudeau would then retire from politics shortly in the early 1980s.

Meech Lake Accord of 1987

From 1985 to 1994, the federalist provincial Liberal Party governed Quebec under Robert Bourassa. The Progressive Conservatives replaced the Liberals federally in 1984 and governed until 1993. Progressive Conservative Prime Minister Brian Mulroney brought together all provincial premiers, including Robert Bourassa, to get the Quebec government's signature on the constitution. The Meech Lake Accord in 1987 recognized Quebec as a "distinct society". The Mulroney government also transferred considerable power over immigration and taxation to Quebec.

The Accord faced stiff opposition from a number of quarters. In Quebec and across Canada, some objected to it arguing that "distinct society" provisions were unclear and could lead to attempts at a gradual independence for Quebec from Canada, and compromising the Charter of Rights. The Parti Québécois, by then led by sovereigntist Jacques Parizeau, opposed the Meech Lake agreement because it did not grant Quebec enough autonomy. The Reform Party in Western Canada led by Preston Manning said that the Accord compromised principles of provincial equality, and ignored the grievances of the Western provinces. Aboriginal groups demanded "distinct society" status similar to Quebec's.

The Accord collapsed in 1990 when Liberal governments came to power in Manitoba and Newfoundland, and did not ratify the agreement. Prime Minister Mulroney, Premier Bourassa, and the other provincial premiers negotiated another constitutional deal, the Charlottetown Accord. It weakened Meech provisions on Quebec and sought to resolve the concerns of the West, and was soundly rejected by a country-wide referendum in 1992.

The collapse of the Meech Lake Accord reshaped the entire Canadian political landscape. Lucien Bouchard, a Progressive Conservative Cabinet Minister who felt humiliated by the defeat of the Meech Lake Accord, led other Quebec Progressive Conservatives and Liberals out of their parties to form the sovereigntist Bloc Québécois. Mario Dumont, leader of the Quebec Liberal Party's youth wing left Bourassa's party to form a "soft nationalist" and sovereigntist Action démocratique du Québec party. The Progressive Conservative Party collapsed in the 1993 election, with Western conservatives voting Reform, Quebec conservatives voting for the Bloc Québécois, and Ontario and Western Montreal voters putting the Liberal Party led by Jean Chrétien into power. Jean Charest in Sherbrooke, Quebec, was one of two Progressive Conservatives left in Parliament, and became party leader.

1995 referendum, its aftermath and fall of interest in Quebec Independence 1995–2018

The Parti Québécois won the 1994 provincial election under the leadership of Jacques Parizeau amid continued anger over the rejection of the Meech Lake Accord. The Parizeau government quickly held a referendum on sovereignty in 1995. Premier Parizeau favoured a unilateral declaration of independence (UDI) followed by negotiations with the federal government if sovereignty were endorsed in the referendum. Lucien Bouchard and Dumont insisted that negotiations with the federal government should come before a declaration of independence. They compromised with an agreement to work together followed by a referendum question that would propose resorting to a UDI by the National Assembly only if negotiations to negotiate a new political "partnership" under Lucien Bouchard failed to produce results after one year.

The sovereigntist campaign remained moribund under Parizeau. It was only with a few weeks to go in the campaign that support for sovereignty skyrocketed to above 50%. On October 30, 1995, the partnership proposal was rejected by an extremely slim margin of less than one per cent.

Parizeau resigned and was replaced by Bouchard. The sovereigntist option was pushed aside until they could establish "winning conditions". Bouchard was suspected by hard-line sovereigntists as having a weak commitment to Quebec independence. Bouchard, in turn, was ill at ease with the ardent nationalism of some elements in the Parti Québécois. He eventually resigned over alleged instances of anti-Semitism within the hard-line wing of the party and was replaced by Bernard Landry. Tensions between the left wing of the party and the relatively fiscal conservative party executive under Bouchard and Landry also led to the formation of the Union des forces progressistes, another social-democratic sovereigntist party that later merged with other left-wing groups to form Québec solidaire.

Mario Dumont and the Action démocratique du Québec put the sovereigntist option aside entirely and ran on a fiscally conservative agenda. They won three consecutive byelections, and their popularity soared fleetingly in opinion polls shortly before the 2003 provincial election, in which they won only four seats and 18% of the popular vote.

The federal Liberal Party Prime Minister Jean Chrétien came under sharp criticism for mishandling the "No" side of the referendum campaign. He launched a hard-line "Plan B" campaign by bringing in Montreal constitutional expert Stéphane Dion, who would attack the perceived ambiguity of the referendum question through a Supreme Court reference on the unilateral secession of Quebec in 1998 and draft the Clarity Act in 2000 to establish strict criteria for accepting a referendum result for sovereignty and a tough negotiating position in the event of a Quebec secession bid.

Jean Charest was lauded by federalists for his impassioned and articulate defense of Canada during the referendum. He left the Progressive Conservative Party to lead the provincial Liberals (no legal relation to its federal counterpart) and a "No" campaign in the event of another referendum, and led his new party to an election victory in 2003. He was re-elected as provincial Premier in the election of 2007, and again in 2008, after having called a snap election.

Prior to the 2018 election, the political status of Quebec inside Canada used to remain a central question. This desire for greater provincial autonomy has often been expressed during the annual constitutional meetings of provincial premiers with the Prime Minister of Canada. In Quebec, no single option regarding autonomy currently gathers a majority of support. Therefore, the question remains unresolved after almost 50 years of debate.

Return of Quebec Autonomy movement and Rise of Coalition Avenir Québec 2018–

In 2018 election, the Coalition Avenir Québec, a Quebec Autonomist Party, won the majority of seats, the first time in Quebec history that neither the Parti Québécois (which also lost its official party status for the first time but however to regain months later[9][10]) nor the Quebec Liberals won a majority. Québec Solidaire also gained a few seats from the Parti Québécois collapse and a couple from Quebec Liberals. This also ended the interest of Quebec independence from Canada for while as seemly half of Quebecers preferred returning to the idea of receiving more political autonomy within Canada.

National Question

The National Question is the debate regarding the future of Quebec and the status of it as a province of Canada. Political parties are organized along ideologies that favor independence from Canada (sovereigntist or separatist) and various degrees of autonomy within Canada (autonomists or federalists). Social democrats, liberals, and conservatives are therefore present in most major parties, creating internal tensions.

Federalism

Canadian Liberalism

Federal Liberals largely defend Quebec's remaining within Canada and keeping the status quo regarding the Canadian constitution. They embrace the liberalism held by former Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and view Canada as a bilingual, multicultural nation based on individual rights. They stress that their nationalism is based on shared civic values, and reject nationalism defined solely on English or French Canadian culture. They defend the need for the federal government to assume the major role in the Canadian system, with occasional involvement in areas of provincial jurisdiction. English-speaking Quebecers, immigrants, and aboriginal groups in northern Quebec strongly support this form of federalism. They may recognize the national status of Quebec, but only informally in the cultural and sociological sense. The traditional vehicle for "status-quo" federalists is the Liberal Party of Canada, although elements of the Conservative Party of Canada have adopted aspects of this position.

The social-democratic New Democratic Party supports Quebec's right to self-determination, but they are firmly opposed to sovereignty, and do not support any major devolving of economic and political powers to Quebec's provincial government.

Federalist Quebec autonomism

The Quebec autonomists are pro-autonomy movement who believe Quebec should seek to gain more political autonomy as a province while remaining a part of the Canadian federation. In 2018 election that the only Autonomist party Coalition Avenir Québec successfully won over most of Quebec population since the Union Nationale in the mid-20th century with this view about the future of Quebec's political status.

Federalist Quebec nationalism

The federalist nationalists are nationalists who believe it is best for the people of Quebec to reform the Canadian confederation in order to accommodate the wish of Quebecers to continue to exist as a distinct society by its culture, its history, its language, and so on. They recognize the existence of the Quebec political (or civic) nation; however, they do not think Quebecers truly wish to be independent from the rest of Canada. Before the arrival of the Parti Québécois, all major Quebec parties were federalist and nationalist. Since then, the party most associated with this view is the Liberal Party of Quebec. On two occasions, federalist nationalists of Quebec attempted to reform the Canadian federation together with allies in other provinces. The 1990 Meech Lake Accord and the 1992 Charlottetown Accord were both ultimately unsuccessful.

Sovereignism (separatism)

Soft nationalists

So-called "soft nationalists" have been characterized as "those who were willing to support Quebec independence only if they could be reasonably reassured that it would not produce economic hardship in the short term",[11] and as "people who call themselves Quebecers first, Canadians second”. They are the voters who gave Brian Mulroney two back-to-back majorities in the 1980s, when he promised to bring Quebec into Canada’s constitution “with honour and enthusiasm.”"[12] They swing between a desire for full independence, and for the recognition of Quebec nationhood and independence within Canada. They are typically swing voters, and tend to be swayed by the political climate, becoming "harder" nationalists when angered by perceived rejection by English Canada (such as the blocking of the Meech Lake Accord [13]), but "softening" when they perceive sovereigntists as threatening the economic and social stability seemingly afforded by Canadian federalism.

Many also view the spectre of Quebec secession as a useful negotiation tool to gain more powers within Confederation. For example, Daniel Johnson, Sr ran on a platform of Égalité ou indépendance (Equality or independence) in the late 1960s as a way of pressing for increased powers from the federal government. Lucien Bouchard expressed similar sentiments as a student.

Sovereigntists

Sovereigntists are moderate nationalists who do not believe Canada to be reformable in a way that could answer what they see as the legitimate wish of Quebecers to govern themselves freely. They opt for the independence of Quebec; however, at the same time, they insist on offering an economic and political partnership to the rest of Canada on the basis of the equality of both nations. The political parties created by the sovereigntists created are the Bloc Québécois and the Parti Québécois, which its members define as a party of social democratic tendency. The Parti Québécois organized a 1980 referendum and a 1995 referendum, each of which could have led to negotiations for independence had it succeeded. The No side prevailed in both, but its margin was very narrow in the second referendum (50.6% No, 49.4% Yes).[14] Sovereigntists find their ideological origins in the Mouvement Souveraineté-Association, René Lévesque's short-lived precursor to the Parti Québécois.

Indépendantistes

Indépendentistes are fully nationalist in outlook. They view the federal government as a successor state to the British Empire, and as a de facto colonizing agent of English Canada. Consequently, they demand complete independence for Quebec, which they view in the context of national liberation movements in Africa and the Caribbean of the 1960s. Independence is seen as the culmination of a natural societal progression, from colonization to provincial autonomy to outright independence.[15] Accordingly, they tend to favor assertive declarations of independence over negotiations, idealizing the Patriote movement of the 1830s. Their ideological origins can be found within the Rassemblement pour l'indépendance nationale headed by Pierre Bourgault, a founding organization of the Parti Québécois.

Political parties

Major political parties

Provincial

- The Quebec Liberal Party (PLQ)

- The Parti Québécois (PQ)

- The Coalition Avenir Québec (CAQ)

- The Québec Solidaire party (QS)

Federal

- The New Democratic Party of Canada (NDP)

- The Bloc Québécois (BQ)

- The Liberal Party of Canada (L)

- The Conservative Party of Canada (C)

- The Green Party of Canada (GPC)

- The People's Party of Canada (PPC)

Other recognized provincial parties

- The Parti vert du Québec (Green Party/PVQ)

- The Bloc pot

- The Parti marxiste-léniniste du Québec

- The Parti Unité Nationale

- Affiliation Quebec

- New Democratic Party of Quebec (founded 2014)

- Conservative Party of Quebec (founded 2009)

Historical parties

- Château Clique/Parti bureaucrate (pre-Confederation)

- Parti canadien/Parti patriote (1806–1837)

- Parti rouge (1847–1867)

- Parti bleu (1854–1867)

- Conservative Party of Quebec (1867–1936)

- Action libérale nationale (1934–1939)

- Union Nationale (1935–1989)

- Fédération du Commonwealth Coopératif/Parti social démocratique du Québec (1939–1961)

- Parti ouvrier-progressiste/Labor-Progressive Party (1944–1960)

- Ralliement créditiste du Québec (1970–1978)

- Bloc populaire (1942–1947)

- Rassemblement pour l'indépendance nationale (1960–1968)

- Parti républicain du Québec (1962–1964)

- Ralliement national (1966–1968)

- Equality Party (1989–2012)

- Nouveau Parti démocratique du Québec/Parti de la Democratie Socialiste (1963–2002)

- Union des forces progressistes (2002–2006)

International organizations

Quebec is a participating government in the international organization the Francophonie, which can be seen as a sort of Commonwealth of Nations for French-speaking countries. Since the 1960s, Quebec has an international network of delegations which represent the Government of Quebec abroad. It is currently represented in 28 foreign locations and includes six General delegations (government houses), four delegations (government offices), nine government bureaus, six trade branches, and three business agents.

Through its civil society, Quebec is also present in many international organizations and forums such as Oxfam, Clowns sans frontières, World Social Forum, and World March of Women.

See also

- Politics of Canada

- Political culture of Canada

- Council of the Federation

- État québécois

- Quebec general elections

- List of Quebec premiers

- List of Quebec leaders of the Opposition

- List of Quebec senators

- National Assembly of Quebec

- Political parties in Quebec

- History of Quebec

- Timeline of Quebec history

- Quebec nationalism

- Quebec sovereigntism

- Quebec federalism

- Quebec Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms

- Reference re Secession of Quebec

- Bill 78

References

- http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/quebec-gives-thumbs-down-to-shariah-law-1.535601

- Supreme Court of Canada. Roncarelli v. Duplessis 1959

- Supreme Court of Canada. Boucher v. the King, S.C.R. 265. p. 305

- Supreme Court of Canada. Saumur v. Quebec 1953

- Option Quebec

- "Five years after Bill 101". CBC Television. February 7, 2012. Retrieved 2012-12-14.

- "Thank you, Montreal! Thank you, Rene!". National Post. November 18, 2006. Retrieved 2012-12-14.

- "The Language Laws of Quebec". Marianopolis College. 23 August 2000. Retrieved 2012-12-14.

- Presse Canadienne (November 22, 2018). "PQ and QS to get official party status in National Assembly". Monteral Gazette. Retrieved December 9, 2018.

- "Parties reach agreement in principle to give PQ and QS official party status". CTV news Monteral. November 22, 2018. Retrieved December 9, 2018.

- Finkel, Alvin (1997). Our Lives: Canada After 1945. James Lorimer & Company. p. 192. ISBN 1550285513.

- Kheiriddin, Tasha (Apr 25, 2011). "Quebec voters mull separation from the separatists". The National Post. Archived from the original on 30 January 2013. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- Archived October 15, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- "Référendum du 30 octobre 1995". Directeur général des élections du Québec. Retrieved September 16, 2014.

- Manifesto of the Rassemblement pour l'indépendance nationale - Independence of Québec. English.republiquelibre.org (2011-01-29). Retrieved on 2013-07-12.

External links

- National Assembly of Quebec

- Government of Quebec Website

- Chief Electoral Officer of Quebec

- La Politique québécoise sur le Web

- Conseil du statut de la femme

- Commission des droits de la personne et des droits de la jeunesse

- The Courts of Quebec Website

- Office de la langue française

- Quebec Ombudsman

- Quebec English School Boards Association

- Tribunal des professions

- Tribunal des droits de la personne

- Tribunal administratif du Québec

- L'État québécois en perspective

- Canadian Governments Compared