Wuxi

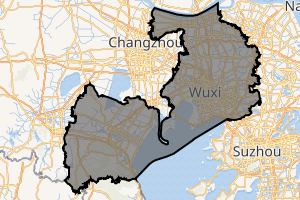

Wuxi (Chinese: 无锡) is a city in southern Jiangsu province, eastern China, 135 kilometers (84 mi) by car to the northwest of downtown Shanghai, between Changzhou and Suzhou.[1] In 2017 it had a population of 3,542,319, with 6,553,000 living in the entire prefecture-level city area.

Wuxi 无锡市 Wusih, Wu Hsi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

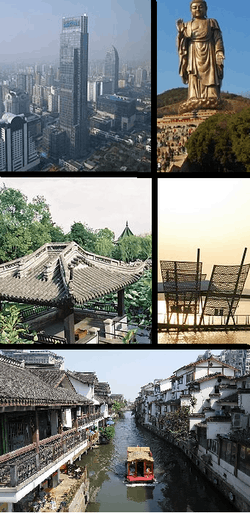

Clockwise from top: Yunfu Mansion, Grand Buddha at Ling Shan, Lihu Lake, city canal, Liyuan Gardens | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Motto(s): Wuxi is full of warmth and water | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Wuxi Location of the CBD in Jiangsu  Wuxi Wuxi (Eastern China)  Wuxi Wuxi (China) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates (Chengzhong Park (城中公园, CBD)): 31°34′42″N 120°18′05″E | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wuxi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.svg.png) "Wuxi" in Simplified (top) and Traditional (bottom) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 无锡 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 無錫 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | PRC Standard Mandarin: Wúxī ROC Standard Mandarin: Wúxí | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Wuxi is a prominent historical and cultural city of China, and has been a thriving economic center since ancient times as a production as an export hub of rice, silk and textiles. In the last few decades it has emerged as a major producer of electrical motors, software, solar technology and bicycle parts. The city lies in the southern delta of the Yangtze River and on Lake Tai, which with its 48 islets is popular with tourists. Notable landmarks include Lihu Park, the Mt. Lingshan Grand Buddha Scenic Area and its 88 meters (289 ft) tall Grand Buddha at Ling Shan statue, Xihui Park, Wuxi Zoo and Taihu Lake Amusement Park and the Wuxi Museum.

The city is served by Sunan Shuofang International Airport, which opened in 2004, the Wuxi Metro, opened in 2014, and the Shanghai–Nanjing Intercity High-Speed Railway which connects it to Shanghai. Jiangnan University, a key national university of “Project 211” and center for scientific research, was originally founded in 1902 but was reconstituted in 2001 with the merger of two other colleges.

Etymology

Wuxi means "without tin" literally. The name "with tin" (有錫) was once adopted during the short-lived Xin Dynasty. Despite varied origin stories, many modern Chinese scholars favor the view that the word is derived from the "old Yue language" or, supposedly, the old Kra–Dai languages.[2][3][4]

History

The history of Wuxi can be traced back to Shang dynasty (1600 – 1046 BC).[5] The tin industry thrived in the area in ancient times but it was eventually depleted, so that when Wuxi was established in 202 BCE during the Han dynasty, it was named "Wuxi" (Without Tin). Administratively, Wuxi became a district of Biling (later Changzhou) and only during the Yuan dynasty (1206–1368) did it become an independent prefecture.[6] Wuxi and Changzhou are considered to be the birthplaces of modern industrialization in China.[7]

Agriculture and the silk industry flourished in Wuxi and the town became a transportation hub under the early Tang Dynasty after the opening of the Grand Canal in 609. It became known as one of the biggest markets for rice in China.[6]

The Donglin Academy, originally founded during the Song dynasty (960-1279) was restored in Wuxi in 1604. Not a school, it served as a public forum, advocating a Confucian orthodoxy and ethics. Many of its academicians were retired court officials or officials deposed in the 1590s due to factionalism.[8]

As a populous county, its eastern part was separated and resulted in the creation of Jinkui county in 1724. Both Wuxi and Jinkui were utterly devastated by the Taiping Rebellion, which resulted in nearly 2/3 of their population being killed.[9] The depleted number of “able-bodied males” (ding, 丁) was only of 72,053 and 138,008 individuals in 1865, versus 339,549 and 258,934 in 1830.[10]

During the Qing dynasty (1636–1912), cotton and silk production flourished in Wuxi.[11] Trade increased with the opening of ports to Shanghai in 1842, and Zhenjiang and Nanjing in 1858. Wuxi became a center of the textile industry in China. Textile mills were built in 1894 and silk reeling establishments known as "filatures" were built in 1904.[6] Wuxi was remained the regional center for the waterborne transport of grain. The opening of the railways to Shanghai and to the cities of Zhenjiang and Nanjing to the northwest in 1908 further increased the exports of rice from the area.[6] Jinkui xian merged into Wuxi County with the onset of the Republic in 1912.[12] Many agricultural laborers and merchants moved to Shanghai in the late 19th century and early 20th century; some prospered in the new factories.[7]

After World War II, Wuxi's importance as an economic center diminished, but it remains a regional manufacturing hub. Tourism has increasingly become important.[6] On April 23, 1949, Wuxi was divided into Wuxi City and Wuxi County, and it became a provincial city in 1953 when Jiangsu Province was founded. In March 1995, several administrative changes were made within Wuxi City and Wuxi County to accommodate for Wuxi New District, with the creation of 19 administrative villages such as Shuofang, Fangqian, Xin’an and Meicun.[5] Jiangnan University was originally founded in 1902, before merging with two other colleges in 2001 to form the modern university.[13]

Geography

Climate

| Climate data for Wuxi (1981–2010 normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 7.5 (45.5) |

9.5 (49.1) |

13.8 (56.8) |

20.0 (68.0) |

25.7 (78.3) |

28.7 (83.7) |

32.4 (90.3) |

31.8 (89.2) |

27.7 (81.9) |

22.7 (72.9) |

16.7 (62.1) |

10.4 (50.7) |

20.6 (69.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 3.5 (38.3) |

5.4 (41.7) |

9.4 (48.9) |

15.2 (59.4) |

20.7 (69.3) |

24.5 (76.1) |

28.5 (83.3) |

27.8 (82.0) |

23.6 (74.5) |

18.2 (64.8) |

12.1 (53.8) |

5.9 (42.6) |

16.2 (61.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 0.4 (32.7) |

2.1 (35.8) |

5.8 (42.4) |

11.1 (52.0) |

16.6 (61.9) |

21.1 (70.0) |

25.3 (77.5) |

24.8 (76.6) |

20.5 (68.9) |

14.6 (58.3) |

8.3 (46.9) |

2.4 (36.3) |

12.8 (54.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 58.8 (2.31) |

57.3 (2.26) |

92.0 (3.62) |

79.9 (3.15) |

96.1 (3.78) |

182.9 (7.20) |

172.1 (6.78) |

143.5 (5.65) |

91.5 (3.60) |

57.4 (2.26) |

56.7 (2.23) |

33.8 (1.33) |

1,122 (44.17) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 75 | 75 | 75 | 74 | 74 | 79 | 79 | 81 | 80 | 77 | 75 | 72 | 76 |

| Source: China Meteorological Administration[14] | |||||||||||||

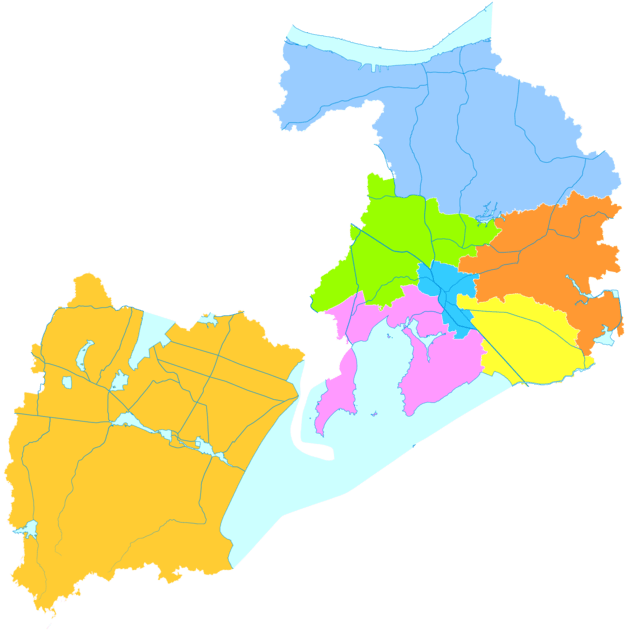

Administrative divisions

The prefecture-level city of Wuxi administers seven county-level divisions, including 5 districts and 2 county-level cities. The information here presented uses the metric system and data from 2010 Census.

These districts are sub-divided into 73 township-level divisions, including 59 towns and 24 subdistricts.

| Map | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subdivision | Chinese | Hanyu Pinyin | Population (2010) | Area (km2) | Density (/km2) |

| City Proper | |||||

| Liangxi District | 梁溪区 | Liángxī Qū | 944,188 | 71.50 | 13,205.43 |

| Suburban | |||||

| Xishan District | 锡山区 | Xīshān Qū | 681,300 | 399.11 | 1,707.05 |

| Huishan District | 惠山区 | Huìshān Qū | 691,059 | 325.12 | 2,125.55 |

| Binhu District | 滨湖区 | Bīnhú Qū | 688,965 | 628.15 | 1,096.82 |

| Xinwu District | 新吴区 | Xīnwú Qū | 536,807 | 220.01 | 2,439.92 |

| Satellite cities (County-level cities) | |||||

| Jiangyin City | 江阴市 | Jiāngyīn Shì | 1,594,829 | 986.97 | 1,615.88 |

| Yixing City | 宜兴市 | Yíxīng Shì | 1,235,476 | 1,996.61 | 618.79 |

| Total | 6,372,624 | 4,627.46 | 1,377.13 | ||

| Defunct: Chong'an District, Nanchang District, & Beitang District | |||||

Economy

Wuxi is a regional business hub, with extensive manufacturing and large industrial parks devoted to new industries. Historically a center of textile manufacturing,[6] the city has adopted new industries such as electric motor manufacturing,[15][16] MRP software development, bicycle and brake manufacturing, and solar technology, with two major photovoltaic companies, Suntech Power[17] and Jetion Holdings Ltd, based in Wuxi. Wuxi Pharma Tech, a major pharmaceutical company, is based in Wuxi[18] The city has a rapidly developing skyline with the opening of three supertall skyscrapers in 2014: Wuxi IFS (339 meters (1,112 ft)[19]), Wuxi Suning Plaza 1 (328 meters (1,076 ft)[20]) and Wuxi Maoye City - Marriott Hotel (303.8 meters (997 ft)[21]).

Since it was established in 1992, Wuxi New District (WND), covering an area of 220 square kilometers (85 sq mi), has evolved to be one of the major industrial parks in China. In 2013, it had a GDP of 121.3 billion yuan ($19.54 billion), and an industrial output value of 276.7 billion yuan, accounting for 15% of production in the Wuxi area. The district includes the Wuxi Hi-tech Industrial Development Zone, Wuxi (Taihu) International Technology Park, Wuxi Airport Industrial Park, China (Wuxi) Industrial Expo Park, China Wu Culture Expo Park, and International Education and Living Community.[22]

Hotels in Wuxi include Wuxi Maoye City – Marriott Hotel, Hilton Hotel's Wuxi-Lingshan Double Tree Resort near the Lingshan Giant Buddha, Kempinski Hotel Wuxi, Landison Square Hotel Wuxi, noted for its Wu jade phoenix sculpture in the lobby, Radisson Blu Resort Wetland Park Wuxi, Sheraton Wuxi Binhu Hotel and Wuxi Hubin Hotel.[23]

Culture and education

Wuxi is one of the major art and cultural centers of Jiangnan Province. The city is known for its Huishan clay figurines, which take their name from the black clay of Huishan Mountain. The figurines have been produced for over 400 years since the Ming dynasty, and are typically large-headed dolls puppies, kittens and chickens.[24] The figurines are believed to promote longevity and exorcise evil spirits. Yixing clay teapots are also of note, made from purple, red and green earth,[25] which is said to enhance the tea drinking experience.[26]

The city is served by Jiangnan University, a key national university of “Project 211” and center for scientific research, which was originally founded in 1902 and established in 1958 as the Wuxi Institute of Light Industry. In 2001 it was reconstituted by the Ministry of Education with the merger of two other colleges to formally establish Jiangnan University.[13] The Taihu University of Wuxi, beside Huishan National Forest Park is a private university and one of the largest in China, covering over 2,000 acres with over 20,000 teachers and students and more than 20 different faculties.[27]

Landmarks

The city lies in the southern Yangtze River delta on Lake Tai, which is the third largest freshwater lake in China, and a rich resource for tourism in the area with cruises. There are 72 peninsulas and peaks and 48 islets, including Yuantouzhu (the Islet of Turtlehead) and Taihu Xiandao (Islands of the Deities).[28]

Parks and gardens

Wuxi has many private gardens or parks built by learned scholars and illustrious people in the past. Lihu Park in Binhu District was built in 1927 and named after the politician and economist Fan Li. The Star of Taihu Lake is noted for its water Ferris wheel. The gardens contains a long embankment with willow trees and a path beside the lake with numerous small bridges and pavilions.[29] On the southwest bank of the lake at the foot of Junzhang Hill is Changguangxi Wetland Park, a 10 kilometers (6.2 mi) stretch of canal connecting Lihu Lake to the north and Taihu Lake to the south. It contains the Shitang Bridge and a lotus pond.[30] Also in Binhu District is Wuxi Zoo and Taihu Lake Amusement Park, an AAAA national landmark with over a 1000 animals including Asian elephant, leopard, chimpanzee, giant panda and white rhinoceros and an ecology and science exhibition and recreation area.[31]

The 30 hectare (74 acres) Mt. Lingshan Grand Buddha Scenic Area on the southwest tip of Wuxi contains the 88 meters (289 ft) tall Grand Buddha at Ling Shan, the world's largest bronze Buddha statue. The Mt Lingshan area also contains the Brahma Palace, Xiangfu Temple, Five Mudra Mandala, Nine Dragons Bathing Sakyamuni (a 7.2 meters (24 ft) statue of Sakyamuni), and numerous other Buddhist sites.[32] Xihui Park, established in 1958 at the foot of Xi Shan to the west of the city, contains Jichang Garden and the Dragon Light Pagoda.[33]

Museums

Wuxi Museum was formally opened on October 1, 2008 following a merger of the Wuxi Revolution Museum, Wuxi Museum and Wuxi Science Museum. Covering over 71,000 square meters (760,000 sq ft) and an exhibition area of 24,100 square meters (259,000 sq ft) it is the largest public cultural building in Wuxi, with 600,000 visitors annually as of 2019. The museum also administers the Chinese National Industry and Commerce Museum of Wuxi, Chengji Art Museum, Zhou Huaimin Painting Museum, Zhang Wentian Former Residence and Wuxi Ancient Stone Inscriptions Museum.[34] Wuxi Art Museum, known as the Wuxi Painting and Calligraphy Institute before the rename in 2011, was established on December 7, 1979 in Chong’an district. The current facility has a space of 1,135 meters (3,724 ft).[35] Hongshan Archaeological Museum in Wuxi New District opened in 2008 and houses artifacts related to the local Wu culture between 770 and 221 BC. The items, which include miniature jade engravings and objects related to burial and musical customs, were unearthed at Hongshan Tomb Complex in 2004.[36]

The Former Residence of Xue Fucheng at No. 152 Xueqian Street in Chong'an district, is the former home of Zue Fencheng, a noted diplomat of the late Qing dynasty and is open to the public.[37]

Sports

Wuxi Sports Center opened in October 1994 and has a capacity of 30,000.[38] It hosts the Wuxi Classic, a snooker event which attracted the biggest names in snooker. Wuxi City Sports Park Stadium hosted the 2017 ITTF Asian-Championships (Ping Pong),[39] and the 2019 World Cup in snooker in June 2019.[40] Major League Baseball based its main Chinese recruitment center in Wuxi since 2009 in Wuxi Development Center at Dongbeitang High School. There Major League Baseball scouts recruit the best players in China in the hopes that they will eventually play professional baseball in America.[41]

Transport

Wuxi is situated on the Shanghai–Nanjing Intercity High-Speed Railway, a 301 kilometers (187 mi) railway which opened on July 1, 2010, linking it directly with the provincial capital of Nanjing, Shanghai and Suzhou.[42] Wuxi Metro began operations in 2014, with two lines totaling 19 miles (31 km) and over 124 miles (200 km) in total expected with new lines opening over the next few decades.[43]Sunan Shuofang International Airport, situated 14 kilometers (8.7 mi) from the city center, opened in 2004, and has direct flights to Beijing, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Hong Kong, Taipei, Singapore, and Osaka.[44]

Wuxi lies along China National Highway 312 which connects Shanghai to central and northwestern China. The 274 kilometers (170 mi) Shanghai-Nanjing Expressway (G42), which opened in November 1996, connecting it to Shanghai, Suzhou, Changzhou, Zhenjiang and other cities in Jiangsu province.[45] The 62.3 kilometers (38.7 mi) Wuxi-Yixing Expressway connects Wuxi with Yixing within the regional prefecture-level area.[46]

Notable people

- Ni Zan, painter (1301–1374)

- Xue Fucheng, diplomat (1838–1894)

- Chen Chi (1912—2005), painter

- Hua Yanjun (1893–1950), musician

- Liu Tianhua, folk musician (1895–1932)

See also

- List of twin towns and sister cities in China

- China Wu Culture Expo Park

- Jiangnan

- List of cities in the People's Republic of China by population

References

- Google (2 September 2019). "Wuxi" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- Zhou, You, Zhenhe, Rujia (1986). 方言与中国文化. Shanghai People's Publishing House. pp. 153–4. ISBN 9787208009653.

- 中国历史大辞典·历史地理卷 [The Great Encyclopaedia of Chinese History, Volume on Historical Geography] (in Chinese). Shanghai Lexicographical Publishing House. 1996. p. 105. ISBN 7-5326-0299-0.

- Zhengzhang, Shangfang (2012). 古吴越地名中的侗台语成分, 古越语地名人名解义. 郑张尚芳语言学论文集 [Zhengzhang Shangfang's Symposium on Linguistics]. Zhonghua Book Company. ISBN 9787101061055.

- "History of Wuxi". Government of Wuxi. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- "Wuxi". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2 September 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- Shi, Henry X (2014). Entrepreneurship in Family Business: Cases from China. Springer. pp. 65–6. ISBN 9783319043043.

- Jones, Derek (2001). Censorship: A World Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 686. ISBN 9781136798641.

- Bell, Lynda S. (1985). "Explaining China's Rural Crisis: Observations From Wuxi County In The Early Twentieth Century". Republican China. Republican China, Volume 11, Issue 1. 11: 15–31. doi:10.1080/08932344.1985.11720078.

- 江苏省志・人口志 [Jiangsu Provincial Gazetteer, Volume on Demography]. Fangzhi Publishing House. pp. 58–9. ISBN 978-7-801-22526-9.

- "Journal of Women's History - Volume 11". Indiana University Press. 1999. p. 103.

- Mass, Jeffrey P. (January 2000). Yoritomo and the Founding of the First Bakufu. Stanford University Press. p. 11. ISBN 9780804780100.

- "History". english.jiangnan.edu.cn. Archived from the original on 2 September 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- 中国气象数据网 - WeatherBk Data (in Chinese). China Meteorological Administration. Retrieved 2020-04-12.

- "WUXI HUADA MOTORS CO., LTD". CCCME. Archived from the original on 2 September 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- "About Us". Wuxi Hongtai Motor Co. Archived from the original on 2 September 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- "About Us". Suntech Power. Archived from the original on 2 September 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- Arthur Yeung, Katherine Xin, Waldemar Pfoertsch (2011). The Globalization of Chinese Companies: Strategies for Conquering . John Wiley & Sons. p. 44. ISBN 9780470828816.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "The Wharf Times Square 1". CTBUH Skyscraper Center. Archived from the original on 2 September 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- "Wuxi Suning Plaza 1". CTBUH Skyscraper Center. Archived from the original on 19 May 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- "Wuxi Maoye City - Marriott Hotel". CTBUH Skyscraper Center. Archived from the original on 19 October 2018. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- "Wuxi New District". China Daily. 5 June 2018. Archived from the original on 2 September 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- "Accommodatations". China Daily. Archived from the original on 12 October 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- Hao, Ni. "Travel Guide of Jiangsu". DeepLogic. p. 293.

- Jiangsu. 2005. ISBN 9787508507569.

- "China's Foreign Trade, Issues 65-74". 1981. p. 34.

- "Taihu University of Wuxi". China Daily. Archived from the original on 2 September 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- "Taihu Lake". Travel China Guide. Archived from the original on 2 September 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- "Lihu Lake". China Daily. Archived from the original on 2 September 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- "Changguangxi Wetland Park". China Daily. Archived from the original on 2 September 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- "Wuxi Zoo and Taihu Lake Amusement Park". China Daily. Archived from the original on 2 September 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- "Mt. Lingshan Grand Buddha Scenic Area". Travel China Guide. Archived from the original on 2 September 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- China. DK Eyewitness Travel Guides. 2016. p. 222. ISBN 9780241279410.

- "Introduction of Wuxi Museum". wxmusuem.com. Archived from the original on 28 May 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- "Wuxi Art Museum (Wuxi Painting and Calligraphy Institute)". China Daily. Archived from the original on 2 September 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- "Hongshan Archaeological Museum". China Daily. Archived from the original on 2 September 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- "The Former Residence of Xue Fucheng". China Daily. Archived from the original on 2 September 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- "Wuxi Sports Center". Emporis. Archived from the original on 2 September 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- "Seamaster 2017 ITTF-Asian Championships - Tournaments". International Table Tennis Federation. Archived from the original on 24 June 2019. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- "Beverly World Cup". Snooker.org. Archived from the original on 23 July 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- "#TBT: Where China Raises Their Future MLB Superstars". That's Mags. 24 May 2018. Archived from the original on 2 September 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- "Shanghai to Nanjing Intercity High Speed Train". Travel China Guide. Archived from the original on 2 September 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- "Wuxi Subway". Travel China Guide. Archived from the original on 2 September 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- "Wuxi Sunan Shuofang International Airport". Travel China Guide. Archived from the original on 2 September 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- "Shanghai-Nanjing Expressway expands with new exit". China Daily. 10 October 2009. Archived from the original on 2 September 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- "Wuxi-Yixing Expressway, China". CCCC Highway Consultants Co. Ltd. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

External links

- Government website of Wuxi (available in Chinese, Japanese and English)

- Wuxi at China Daily

.jpg)