Chinese Indonesians

Chinese Indonesians (Indonesian: Orang Indonesia keturunan Tionghoa) or (in Indonesia) Orang Tionghoa are Indonesians whose ancestors arrived from China at some stage in the last eight centuries. Most Chinese Indonesians are descended from Southern Chinese immigrants.

| |

|---|---|

Slogan proclaiming that Chinese Indonesians stand together with Native Indonesians in support of the country's independence, c. 1946. | |

| Total population | |

| 2,832,510 (2010 census) 1.20% of the Indonesian population[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

North Sumatra, Riau, Riau Islands, Bangka-Belitung, Banten, Jakarta, Central Java, East Java, West Kalimantan, North Sulawesi As well as a large diaspora populace in: | |

| Languages | |

Primarily Indonesian, Javanese. English, Hakka and Hokkien; Henghua, Chaozhounese, Fuzhounese, Mandarin, Hainanese, Cantonese and Hoisanese (minority groups) | |

| Religion | |

Predominantly Christianity (Protestantism and Roman Catholicism) and Buddhism Minorities of Islam, Confucianism and Taoism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Chinese Indonesians | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 印度尼西亞華人 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 印度尼西亚华人 | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 印尼華人 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 印尼华人 | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Second alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 印尼華僑 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 印尼华侨 | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

Chinese people have lived in the Indonesian archipelago since at least the 13th century. Many came initially as sojourners (temporary residents), intending to return home in their old age.[6] Some, however, stayed in the region as economic migrants. Their population grew rapidly during the colonial period when workers were contracted from their home provinces in southern China. Discrimination against Chinese Indonesians has occurred since the start of Dutch colonialism in the region, although government policies implemented since 1998 have attempted to redress this. Resentment of ethnic Chinese economic aptitude grew in the 1950s as Native Indonesian merchants felt they could not remain competitive. In some cases, government action propagated the stereotype that ethnic Chinese-owned conglomerates were corrupt. Although the 1997 Asian financial crisis severely disrupted their business activities, reform of government policy and legislation removed a number of political and social restrictions on Chinese Indonesians.

The development of local Chinese society and culture is based upon three pillars: clan associations, ethnic media and Chinese language schools.[7][8] These flourished during the period of Chinese nationalism in the final years of China's Qing dynasty and through the Second Sino-Japanese War; however, differences in the objective of nationalist sentiments brought about a split in the population. One group supported political reforms in China, while others worked towards improved status in local politics. The New Order government (1967–1998) dismantled the pillars of ethnic Chinese identity in favor of assimilation policies as a solution to the so-called "Chinese Problem".

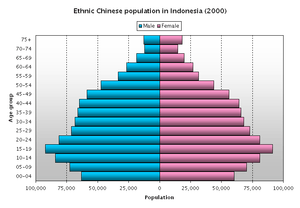

The Chinese Indonesian population of Sumatra accounts for nearly half of the group's national population. They are generally more urbanized than Indonesia's indigenous population but significant rural and agricultural communities still exist throughout the country. Declining fertility rates have resulted in an upward shift in the population pyramid, as the median age increases. Emigration has contributed to a shrinking population and communities have emerged in more industrialized nations in the second half of the 20th century. Some have participated in repatriation programs to the People's Republic of China, while others emigrated to neighbouring Singapore and Western countries to escape anti-Chinese sentiment.[9] Among the overseas residents, their identities are noticeably more Indonesian than Chinese.[10]

Classification

The term "Chinese Indonesian" has never been clearly defined, especially for the period before 1900. There was no Indonesian identity or nationality before the 20th century. The ethno-political category Han Chinese was also poorly defined before the rise of modern Chinese nationalism in the late 19th century. At its broadest, the term "Chinese Indonesian" is used to refer to anyone from, or having an ancestor from, the present-day territory of China. This usage is problematic because it conflates Han Chinese with other ethnic groups under Chinese rule. For instance, Admiral Zheng He (1371–1433), who led several Chinese maritime expeditions into Southeast Asia, was a Muslim from Yunnan and was not of Chinese ancestry, yet he is generally characterized as "Chinese". This broad use is also problematic because it prioritizes a line of descent from China over all other lines and may conflict with an individual's own self-identity. Many people who identify as Chinese Indonesian are of mixed Chinese and Indonesian descent. Indonesia's president Abdurrahman Wahid (1940-2009) is widely believed to have some Chinese ancestry, but he did not regard himself as Chinese.

Some narrower uses of the term focus on culture, defining as "Chinese Indonesian" those who choose to prioritize their Chinese ancestry, especially those who have Chinese names or follow aspects of Chinese religion or culture. Within this cultural definition, a distinction has commonly been made between peranakan and totok Chinese. Peranakan were generally said to have mixed Chinese and local ancestry and to have developed a hybrid culture that included elements from both Chinese and local cultures. Totoks were generally said to be first-generation migrants and to have retained a strong Chinese identity.

Other definitions focus on the succession of legal classifications that have separated "Chinese" from other inhabitants of the archipelago. Both the Dutch East India Company and the Dutch colonial government (from 1815) applied complex systems of ethnic classification to their subjects, based on religion, culture and place of origin. Chinese Indonesians were sometimes classified as "Natives", sometimes as "Chinese", sometimes as "Foreign Orientals", a category that included Arabs, Indians and Siamese.[11] After independence, the community was divided between those who accepted Indonesian citizenship and those who did not. Under the New Order of President Suharto, citizens of Chinese descent were formally classified as "Indonesian citizens of foreign descent" (Warga Negara Indonesia keturunan asing). In public discourse they were distinguished from native Indonesians as "non-native" (non-pribumi or non-pri).

History

Early interactions

_en_Tek_Hwa_Seng_bij_Poeloe_Samboe_TMnr_10010680.jpg)

The first recorded movement of people from China into Maritime Southeast Asia was the arrival of Mongol forces under Kublai Khan that culminated in the invasion of Java in 1293. Their intervention hastened the decline of the classical kingdoms such as Singhasari and precipitated the rise of the Majapahit empire.[12]

Chinese Muslim traders from the eastern coast of China arrived at the coastal towns of Indonesia and Malaysia in the early 15th century. They were led by the mariner Zheng He, who commanded several expeditions to Southeast Asia between 1405 and 1430. In the book Yingya Shenglan, his translator Ma Huan documented the activities of the Chinese Muslims in the archipelago and the legacy left by Zheng He and his men.[13] These traders settled along the northern coast of Java, but there is no documentation of their settlements beyond the 16th century. The Chinese Muslims were likely to have been absorbed into the majority Muslim population.[14] Between 1450 and 1520, the Ming Dynasty's interest in southeastern Asia reached a low point and trade, both legal and illegal, rarely reached the archipelago.[15] The Portuguese made no mention of any resident Chinese minority population when they arrived in Indonesia in the early 16th century.[16] Trade from the north was re-established when China legalized private trade in 1567 through licensing 50 junks a year. Several years later silver began flowing into the region, from Japan, Mexico, and Europe, and trade flourished once again. Distinct Chinese colonies emerged in hundreds of ports throughout southeastern Asia, including the pepper port of Banten.[15]

Some Chinese traders avoided Portuguese Malacca after it fell to the Portuguese in the 1511 Capture of Malacca.[17] Many Chinese, however, cooperated with the Portuguese for the sake of trade.[18] Some Chinese in Java assisted in Muslim attempts to reconquer the city using ships. The Javanese–Chinese participation in retaking Malacca was recorded in "The Malay Annals of Semarang and Cerbon".[17]

Chinese in the archipelago under Dutch East India Company rule (1600–1799)

By the time the Dutch arrived in the early 17th century, major Chinese settlements existed along the north coast of Java. Most were traders and merchants, but they also practiced agriculture in inland areas. The Dutch contracted many of these immigrants as skilled artisans in the construction of Batavia (Jakarta) on the northwestern coast of Java.[14] A recently created harbor was selected as the new headquarters of the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie, VOC) in 1609 by Jan Pieterszoon Coen. It grew into a major hub for trade with China and India. Batavia became home to the largest Chinese community in the archipelago and remains so in the 21st century.[19] Coen and other early Governors-General promoted the entry of Chinese immigrants to new settlements "for the benefit of those places and for the purpose of gathering spices like cloves, nutmeg, and mace".[20] The port's Chinese population of 300–400 in 1619 had grown to at least 10,000 by 1740.[21] The Dutch Company ruled migrant ethnic groups in Batavia using 'officers' drawn from each community, usually with the title kapitan or majoor. These officers had a high degree of authority over their community and undertook negotiations between the community and the Company authorities.[22] Dutch colonial rule saw the beginning of anti-Chinese policies, including killings and ghettoization.[23]

Most of those who settled in the archipelago had already severed their ties with the mainland and welcomed favorable treatment and protection under the Dutch.[24] Some became "revenue farmers", middlemen within the corporate structure of the VOC, tasked with collecting export–import duties and managing the harvest of natural resources;[25] although this was highly profitable, it earned the enmity of the pribumi population. Others worked as opium farmers.[26] Following the 1740 Batavia massacre and ensuing war, in which the Chinese rebelled against the Dutch,[27] the Dutch attempted to place a quota on the number of Chinese who could enter the Indies. Amoy was designated as the only immigration port to the archipelago, and ships were limited to a specified number of crew and passengers depending on size. This quota was adjusted at times to meet demand for overseas workers, such as in July 1802 when sugar mills near Batavia were in need of workers.[28]

Chinese who married local Javanese women and converted to Islam created a distinct Chinese Muslim Peranakan community in Java.[29] Chinese rarely had to convert to Islam to marry Javanese abangan women but a significant amount of their offspring did, and Batavian Muslims absorbed the Chinese Muslim community which was descended from converts.[30] Adoption of Islam back then was a marker of peranakan status which it no longer means. The Semaran Adipati and the Jayaningrat families were of Chinese origin.[31][32]

Chinese in the archipelago under Dutch colonial rule to 1900

When the VOC was nationalized on 31 December 1799, many freedoms the Chinese experienced under the corporation were eliminated by the Dutch government. Among them was the Chinese monopoly on the salt trade which had been granted by the VOC administration.[33] An 1816 regulation introduced a requirement for the indigenous population and Chinese traveling within the territory to obtain a travel permit. Those who did not carry a permit faced arrest by security officers. The Governor-General also introduced a resolution in 1825 which forbade "foreign Asians in Java such as Malays, Buginese and Chinese" from living within the same neighborhood as the native population.[34] Following the costly Java War (1825–1830) the Dutch introduced a new agrarian and cultivation system that required farmers to "yield up a portion of their fields and cultivate crops suitable for the European market". Compulsory cultivation restored the economy of the colony, but ended the system of revenue farms established under the VOC.[35]

The Chinese were perceived as temporary residents and encountered difficulties in obtaining land rights. Europeans were prioritized in the choice of plantation areas, while colonial officials believed the remaining plots must be protected and preserved for the indigenous population. Short-term and renewable leases of varying lengths[lower-alpha 1] were later introduced as a temporary measure, but many Chinese remained on these lands upon expiration of their contracts and became squatters.[36] At the beginning of the 20th century, the colonial government began to implement the "Ethical Policy" to protect the indigenous population, casting the Chinese as the "foremost enemy of the natives". Under the new policy, the administration increased restrictions on Chinese economic activities, which they believed exploited the native population.[37]

Powerful Chinese families were described as the 'Cabang Atas' ("upper branch") of colonial society, forming influential bureaucratic and business dynasties, such as the Kwee family of Ciledug and the Tan family of Cirebon.

In western Borneo, the Chinese established their first major mining settlement in 1760. Ousting Dutch settlers and the local Malay princes, they joined into a new republic known as Lanfang. By 1819, they came into conflict with the new Dutch government and were seen as "incompatible" with its objectives, yet indispensable for the development of the region.[38] The Bangka–Belitung Islands also became examples of major settlements in rural areas. In 1851, 28 Chinese were recorded on the islands and, by 1915, the population had risen to nearly 40,000 and fishing and tobacco industries had developed. Coolies brought into the region after the end of the 19th century were mostly hired from the Straits Settlements owing to recruiting obstacles that existed in China.[39]

Divided nationalism (1900–1949)

The Chinese revolutionary figure Sun Yat-sen visited southeast Asia in 1900,[40] and, later that year, the socio-religious organization Tiong Hoa Hwe Koan (中華 會館), also known as the Chinese Association, was founded. Their goal was to urge ethnic Chinese in the Indies to support the revolutionary movement in China. In its effort to build Chinese-speaking schools the association argued that the teaching of the English and Chinese languages should be prioritized over Dutch, to provide themselves with the means of taking, in the words of Phoa Keng Hek, "a two or three-day voyage (Java–Singapore) into a wider world where they can move freely" and overcome restrictions of their activities.[41] Several years later, the Dutch authorities abandoned its segregation policies, abolished travel permits for the ethnic Chinese, and allowed them to freely move throughout the colony. The 1911 Xinhai Revolution and the 1912 founding of the Republic of China coincided with a growing Chinese–nationalist movement within the Indies.[40]

Although there was no recognizable nationalist movement among the indigenous population until 1908, Dutch authorities feared that nationalist sentiments would spread with the growth of ethnically mixed associations, known as kongsi. In 1911, some Javanese members of the Kong Sing association in Surakarta broke away and clashed with the ethnic Chinese. This incident led to the creation of Sarekat Islam, the first organized popular nationalist movement in the Indies. Indigenous groups saw the Chinese nationalist sentiment as "haughty", leading to mutual antagonism.[42] The anti-Chinese sentiment spread throughout Java in 1918 and led to violent attacks orchestrated by members of Sarekat Islam on the ethnic Chinese in Kudus.[43] Following this incident, the left-wing Chinese nationalist daily Sin Po called on both sides to work together to improve living conditions because it considered most ethnic Chinese, like most of the indigenous population, to be poor.[44]

Sin Po first went into print in 1910 and began gaining momentum as the leading advocate of Chinese political nationalism in 1917. The ethnic Chinese who followed its stream of thought refused any involvement with local institutions and would only participate in politics relating to mainland China.[46] A second stream was later formed by wealthy ethnic Chinese who received an education at Dutch-run schools. This Dutch-oriented group wished for increased participation in local politics, Dutch education for the ethnic Chinese, and the furthering of ethnic Chinese economic standing within the colonial economy. Championed by the Volksraad's Chinese representatives, such as Hok Hoei Kan, Loa Sek Hie and Phoa Liong Gie, this movement gained momentum and reached its peak with the Chung Hwa Congress of 1927 and the 1928 formation of the Chung Hwa Hui party, which elected Kan as its president. The editor-in-chief of the Madjallah Panorama news magazine criticized Sin Po for misguiding the ethnic Chinese by pressuring them into a Chinese-nationalist stance.[47]

._De_Chinese_Politie_Keamanan_te_Bagan%2C_Bestanddeelnr_15074.jpg)

In 1932, pro-Indonesian counterparts founded the Partai Tionghoa Indonesia to support absorption of the ethnic Chinese into the Javanese population and support the call for self-government of Indonesia. Members of this group were primarily peranakan.[48] This division resurfaced at the end of the period of Japanese occupation (1942–1945).[49] Under the occupation ethnic Chinese communities were attacked by Japanese forces, in part owing to suspicions that they contained sympathizers of the Kuomintang as a consequence of the Second Sino-Japanese War. When the Dutch returned, following the end of World War II, the chaos caused by advancing forces and retreating revolutionaries also saw radical Muslim groups attack ethnic Chinese communities.[43]

Although revolutionary leaders were sympathetic toward the ethnic Chinese, they were unable to stop the sporadic violence. Those who were affected fled from the rural areas to Dutch-controlled cities, a move many Indonesians saw as proof of pro-Dutch sentiments.[50] There was evidence, however, that Chinese Indonesians were represented and participated in independence efforts. Four members of the Investigating Committee for Preparatory Work for Independence (BPUPK) were Chinese: Liem Koen Hian, Oey Tiang Tjoei, Oey Tjong Hauw and Tan Eng Hoa. Yap Tjwan Bing was the sole Chinese member of the Preparatory Committee for Indonesian Independence (PPKI).[51] Ong Eng Die became a government minister in the Indonesian Republic.

Loyalty in question (1950–1966)

The Netherlands relinquished its territorial claims in the archipelago (with the exception of West Papua) following the 1949 Round Table Conference. In the same year that the Kuomintang retreated to Taiwan, allowing the Communist Party of China to take control of mainland China. Most Chinese Indonesians considered a communist China less attractive than a newly independent Indonesia, but in the archipelago their loyalties were questioned. Ethnic Chinese born in the Dutch East Indies whose parents were domiciled under Dutch administration were regarded as citizens of the new state according to the principle of jus soli, or "right of the soil".[50] However, Chinese law considered a person as a Chinese citizen according to the principle of jus sanguinis, or right of blood. This meant that all Indonesian citizens of Chinese descent were also claimed as citizens by the People's Republic of China. After several attempts by both governments to resolve this issue, Indonesia and China signed a Dual Nationality Treaty on the sidelines of the 1955 Asian–African Conference in Bandung. One of its provisions permitted Indonesians to renounce Chinese citizenship if they wished to hold Indonesian citizenship only.[52]

As many as 390,000 ethnic Chinese, two-thirds of those with rightful claims to Indonesian citizenship renounced their Chinese status when the treaty came into effect in 1962.[52] On the other hand, an estimated 60,000 ethnic Chinese students left for the People's Republic of China in the 1950s and early 1960s.[54] The first wave of students were almost entirely educated in Chinese-language schools, but were not able to find opportunities for tertiary education in Indonesia. Seeking quality scientific professions, they entered China with high hopes for their future and that of the mainland.[53] Subsequent migrations occurred in 1960 as part of a repatriation program and in 1965–1966 following a series of anti-communist violence that also drew anger toward the ethnic Chinese. As many as 80 percent of the original students who entered the mainland eventually became refugees in Hong Kong.[54] During China's Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), Red Guards questioned the loyalty of the returned overseas Chinese because of their foreign connections.[55] They were attacked as "imperialists", "capitalists", "spies", "half-breeds", and "foreign devils".[53]As most had grown up in an urban environment they were sent to the countryside, told to "rebel against their own class background", and eventually lost contact with their families.[56]

In 1959, following the introduction of soft-authoritarian rule through Guided Democracy, the Indonesian government and military began placing restrictions on alien residence and trade. These regulations culminated in the enactment of Presidential Regulation 10 in November 1959, banning retail services by non-indigenous persons in rural areas. Ethnic Chinese, Arab, and Dutch businessmen were specifically targeted during its enforcement to provide a more favorable market for indigenous businesses.[58] This move was met with protests from the Chinese government and some circles of Indonesian society. Javanese writer Pramoedya Ananta Toer later criticized the policies in his 1961 book Hoakiau di Indonesia. An integrationist movement, led by the Chinese-Indonesian organisation Baperki (Badan Permusjawaratan Kewarganegaraan Indonesia), began to gather interest in 1963, including that of President Sukarno. However, a series of attacks on ethnic Chinese communities in West Java in May proved it to be short-lived, despite the government's condemnation of the violence.[59] When Baperki was branded a communist organization in 1965 the ethnic Chinese were implicated by association; this was exacerbated in the public mind by the People's Republic of China's communism. As many as 500,000 people, the majority of them Javanese Abangan Muslims and Balinese Indonesians but including a minority of several thousand ethnic Chinese, were killed in the anti-communist purge[lower-alpha 2] which followed the failed coup d'état, suspected as being communist-led, on 30 September 1965.[60]

Managing the "Chinese Problem" (1967–1998)

When the New Order government of General Suharto came into power in 1966–1967, it introduced a political system based only on the Pancasila (five principles) ideology. To prevent the ideological battles that occurred during Sukarno's presidency from resurfacing, Suharto's "Pancasila democracy" sought a depoliticized system in which discussions of forming a cohesive ethnic Chinese identity were no longer allowed.[61] A government committee was formed in 1967 to examine various aspects of the "Chinese Problem" (Masalah Cina) and agreed that forced emigration of whole communities was not a solution: "The challenge was to take advantage of their economic aptitude whilst eliminating their perceived economic dominance."[62] The semi-governmental Institute for the Promotion of National Unity (Lembaga Pembina Kesatuan Bangsa, LPKB) was formed to advise the government on facilitating assimilation of Chinese Indonesians. This process was done through highlighting the differences between the ethnic Chinese and the indigenous pribumi, rather than seeking similarities. Expressions of Chinese culture through language, religion, and traditional festivals were banned and the ethnic Chinese were pressured to adopt Indonesian-sounding names.[63][64]

During the 1970s and 1980s, Suharto and his government brought in Chinese Indonesian businesses to participate in the economic development programs of the New Order while keeping them highly vulnerable to strengthen the central authority and restrict political freedoms. Patron–client relationships, mainly through the exchange of money for security, became an accepted norm among the ethnic Chinese as they maintained a social contract through which they could claim a sense of belonging in the country. A minority of the economic elite of Indonesian society, both those who were and were not ethnic Chinese, secured relationships with Suharto's family members and members of the military for protection, while small business owners relied on local law enforcement officials.[63] Stereotypes of the wealthy minority became accepted as generalized facts but failed to acknowledge that said businessmen were few in number compared to the small traders and shop owners. In a 1989 interview conducted by scholar Adam Schwarz for his book A Nation in Waiting: Indonesia's Search for Stability, an interviewee stated that, "to most Indonesians, the word 'Chinese' is synonymous with corruption".[65] The economic role of the ethnic Chinese was contradictory because it did not translate to acceptance of their status in the greater society. They were politically weak and often faced social harassment.[66]

Anti-Chinese sentiment gathered intensity through the 1990s. President Suharto gathered the most powerful businessmen—mostly Chinese Indonesians—in a nationally televised 1990 meeting at his private ranch, calling on them to contribute 25 percent of their shares to cooperatives. Commentators described the spectacle as "good theatre", as it only served to reinforce resentment and suspicion of the ethnic Chinese among the indigenous population. Major riots broke out in Situbondo (October 1996), Tasikmalaya (December 1996), and Rengasdengklok (January 1997).[68]

When Suharto entered his seventh term as president, following an uncontested election on 10 March 1998, Indonesian students began a series of major demonstrations in protest of the New Order regime which continued for weeks and culminated in the shootings of four students by security forces at Trisakti University in May.[69] The incident sparked major violence in several cities during 12–15 May. Property and businesses owned by Chinese Indonesians were targeted by mobs, and over 100 women were sexually assaulted;[67] this aspect of the riots, though generally accepted as true,[70] has been denied by several Indonesian groups.[71] In the absence of security forces, large groups of men, women, and children looted and burned the numerous shopping malls in major cities. In Jakarta and Surakarta over 1,000 people—both Chinese and non-Chinese—died inside shopping malls.[70] Tens of thousands of ethnic Chinese fled the country following these events,[72] and bankers estimated that US$20 billion of capital had left the country in 1997–1999 to overseas destinations such as Singapore, Hong Kong, and the United States.[73]

Social policy reforms (1999–present)

Suharto unexpectedly resigned on 21 May 1998, one week after he returned from a Group of 15 meeting in Cairo, which took place during the riots.[74] The reform government formed by his successor Bacharuddin Jusuf Habibie began a campaign to rebuild the confidence of Chinese Indonesians who had fled the country, particularly businessmen. Along with one of his envoys James Riady, son of financial magnate Mochtar Riady, Habibie appealed to Chinese Indonesians seeking refuge throughout East Asia, Australia, and North America to return and promised security from various government ministries as well as other political figures, such as Abdurrahman Wahid and Amien Rais. Despite Habibie's efforts he was met with skepticism because of remarks he made, as vice president and as president, which suggested that the message was insincere.[75] One special envoy described Chinese Indonesians as the key to restoring "badly needed" capital and economic activity, prioritizing businessmen as the target of their pleas. Others, including economist Kwik Kian Gie, saw the government's efforts as perpetuating the myth of Chinese economic domination rather than affirming the ethnic Chinese identity.[76]

Symbolic reforms to Chinese Indonesian rights under Habibie's administration were made through two Presidential Instructions. The first abolished the use of the terms "pribumi" and "non-pribumi" in official government documents and business. The second abolished the ban on the study of Mandarin Chinese[lower-alpha 3] and reaffirmed a 1996 instruction that abolished the use of the SBKRI to identify citizens of Chinese descent. Habibie established a task force to investigate the May 1998 violence, although his government later dismissed its findings.[77] As an additional legal gesture Indonesia ratified the 1965 Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination on 25 May 1999.[78] In 2000 the newly elected President Wahid abolished the ban on public displays of Chinese culture and allowed Chinese traditions to be practised freely, without the need of a permit. Two years later President Megawati Sukarnoputri declared that the Chinese New Year (Imlek) would be marked as a national holiday from 2003.[79] In addition to Habibie's directive on the term "pribumi", the legislature passed a new citizenship law in 2006 defining the word asli ("indigenous") in the Constitution as a natural born person, allowing Chinese Indonesians to be eligible to run for president. The law further stipulates that children of foreigners born in Indonesia are eligible to apply for Indonesian citizenship.[80]

The post-Suharto era saw the end of discriminatory policy against Chinese Indonesians. Since then, numbers of Chinese Indonesians began to take part in the nation's politics, government and administrative sector. The Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono presidency (2004–2014) saw the first female Chinese Indonesian minister Mari Elka Pangestu as Minister of Trade (2004-2011) and Minister of Tourism and Creative Economy (2011-2014).[81] Another notable Chinese Indonesian in Indonesian politics is Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, former Regent of East Belitung (2005–2006) and first Governor of Jakarta (2014–2017) of Chinese descent.

However, discrimination and prejudice against Indonesian Chinese continues in the 21st century. On 15 March 2016, Indonesian Army General Suryo Prabowo commented that the incumbent governor of Jakarta, Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, should "know his place lest the Indonesian Chinese face the consequences of his action". This controversial comment was considered to hearken back to previous violence against the Indonesian Chinese.[82] On 9 May 2017, Basuki Tjahaja Purnama was sentenced to two years in prison after being found guilty of committing a criminal act of blasphemy.[83]

Origins

Chinese immigrants to the Indonesian archipelago almost entirely originated from various ethnic groups especially the Tanka people of what are now the Fujian and Guangdong provinces in southern China, areas known for their regional diversity.[84] Nearly all Chinese Indonesians are either patrilineal descendants of these early immigrants or new immigrants born in mainland China.[85]

The first group of Chinese people to settle in large numbers to escape the coastal ban were the most affected Tanka boat people, other came in much smaller numbers, Teochews from Chaozhou,[86] the Hakkas from Chengxiang county (now renamed Meixian), Huizhou (pronounced Fuizhew in Hakka) and rural county of Dabu (pronounced Thaipo in Hakka), the Cantonese from Guangdong and various different ethnic dialect groups who left the trading city ports of southern Fujian including the ethnic Tanka, Hakkas, etc. Descendants of Hokkien Tanka are the dominant group in eastern Indonesia, Central and East Java and the western coast of Sumatra. Teochews, southern neighbors of the Hokkien, are found throughout the eastern coast of Sumatra, in the Riau Archipelago, and in western Borneo. They were preferred as plantation laborers in Sumatra but have become traders in regions where the Hokkien are not well represented.[87]

From 1628 to 1740, there were more 100,000 Hakkas from Huizhou living in Batavia and Java island.[88]

The Hakka, unlike the Hokkien and the Teochew, originate from the mountainous inland regions of Guangdong and do not have a maritime culture.[87] Owing to the unproductive terrain of their home region, the Hakka emigrated out of economic necessity in several waves from 1850 to 1930 and were the poorest of the Chinese immigrant groups. Although they initially populated the mining centers of western Borneo and Bangka Island, Hakkas became attracted to the rapid growth of Batavia and West Java in the late 19th century.[89]

The Cantonese people, like the Hakka, were well known throughout Southeast Asia as mineworkers. Their migration in the 19th century was largely directed toward the tin mines of Bangka, off the east coast of Sumatra. Notable traditionally as skilled artisans, the Cantonese benefited from close contact with Europeans in Guangdong and Hong Kong by learning about machinery and industrial success. They migrated to Java about the same time as the Hakka but for different reasons. In Indonesia's cities, they became artisans, machine workers, and owners of small businesses such as restaurants and hotel-keeping services. The Cantonese are evenly dispersed throughout the archipelago and number far less than the Hokkien or the Hakka. Consequently, their roles are of secondary importance in the Chinese communities.[89]

Demographics

Indonesia's 2000 census reported 2,411,503 citizens (1.20 percent of the total population) as ethnic Chinese.[lower-alpha 4] An additional 93,717 (0.05 percent) ethnic Chinese living in Indonesia were reported as foreign citizens, mostly those of the People's Republic of China and Republic of China, who may not be able to pay the cost of becoming an Indonesian citizen.[91] Because the census employed the method of self-identification, those who refused to identify themselves as ethnic Chinese, or had assumed the identity of other ethnic groups, either because of assimilation or mixed-parentage, or fear of persecution,[92] were recorded as non-Chinese.[7] It is also likely that there are around 6 to 8 millions Chinese living in Indonesia according to several external estimates.[93]

Past estimates on the exact number of Chinese Indonesians relied on the 1930 Dutch East Indies census, which collected direct information on ethnicity.[94] This census reported 1.23 million self-identified ethnic Chinese living in the colony, representing 2.03 percent of the total population, and was perceived to be an accurate account of the group's population.[95] Ethnic information would not be collected again until the 2000 census and so was deduced from other census data, such as language spoken and religious affiliation, during the intermediate years.[96] In an early survey of the Chinese Indonesian minority, anthropologist G. William Skinner estimated that between 2.3 million (2.4 percent) and 2.6 million (2.7 percent) lived in Indonesia in 1961.[85] Former foreign minister Adam Malik provided a figure of 5 million in a report published in the Harian Indonesia daily in 1973.[97] Many media and academic sources subsequently estimated between 4 and 5 percent of the total population as ethnic Chinese regardless of the year.[96] Estimates during the 2000s have placed the figure between 6 and 7 million,[98] and the Overseas Compatriot Affairs Commission of the Republic of China estimated a population as high as 7.67 million in 2006.[99]

According to 2010 population census, 22.3 percent of Chinese Indonesians lived in the capital city of Jakarta, located on the island of Java. When the island's other provinces—Banten, West Java, Central Java, Yogyakarta, and East Java—are included, this population accounted for around half (51.8 percent) of all Chinese Indonesians.[1] This data does not count the number of ethnic Chinese that have foreign citizenship. 8.15 percent of West Kalimantan's population is ethnic Chinese, followed by Bangka–Belitung Islands (8.14 percent), Riau Islands (7.66 percent), Jakarta (6.58 percent), North Sumatra (5,75 percent), Riau (1.84 percent). In each of the remaining provinces, Chinese Indonesians account for 1 percent or less of the provincial population.[100] Most Chinese Indonesians in North Sumatra lived in the provincial capital of Medan; they are one of major ethnic groups in the city with the Bataks and Javanese people, but in the province, they constituted only a small percentage because of the relatively large population of the province, the sizeable Chinese population also has presence in Binjai, Tanjungbalai and Pematangsiantar city.[101] Bangka–Belitung, West Kalimantan, and Riau are grouped around the hub of ethnic Chinese economic activity in Singapore and, with the exception of Bangka–Belitung, these settlements existed long before Singapore's founding in 1819.[102]

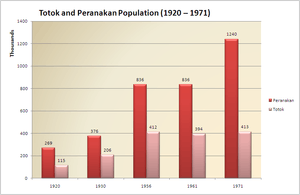

The ethnic Chinese population in Indonesia grew by an average of 4.3 percent annually between 1920 and 1930. It then slowed owing to the effects of the Great Depression and many areas experienced a net emigration. Falling growth rates were also attributed to a significant decrease in the number of Chinese immigrants admitted into Indonesia since the 1950s.[94] The population is relatively old according to the 2000 census, having the lowest percentage of population under 14 years old nationwide and the second-highest percentage of population over 65. Their population pyramid had a narrow base with a rapid increase until the 15–19 age group, indicating a rapid decline in total fertility rates. This was evidenced by a decline in the absolute number of births since 1980. In Jakarta and West Java the population peak occurred in the 20–24 age group, indicating that the decline in fertility rates began as early as 1975. The upper portion of the pyramid exhibited a smooth decline with increasing population age.[103] It is estimated that 60.7 percent of the Chinese Indonesian population in 2000 constitutes the generation that experienced political and social pressures under the New Order government. With an average life expectancy of 75 years, those who spent their formative years prior to this regime will completely disappear by 2032.[104]

According to the last 2010 population census, the self-identified Chinese Indonesian population is 2,832,510. There is a growth of 17.5% from 2000 census, although some of them are because the census bureau improved its counting methodology between 2000 and 2010. During the 2000 census, it only published data for the eight largest ethnic groups in each province. Because Chinese Indonesians in some provinces did not have a large enough population, they were left off the list. This error was only corrected in 2008 when Aris Ananta, Evi Nuridya Arifin, and Bakhtiar from the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies in Singapore published a report that accounted for all Chinese Indonesian populations using raw data from BPS.

Emigrant communities

Emigration by Chinese Indonesians became significant after Indonesian independence in 1945. Large numbers of Chinese Indonesians repatriated to China, Taiwan and Hong Kong throughout the following years, while others moved to more industrialized regions around the world.

Although these migrants possessed a Chinese heritage, they were often not identified as such; this trend has continued into the modern day.[105] There have been several independent estimates made of the Chinese Indonesian population living in other countries. James Jupp's The Australian People encyclopedia estimated that half of over 30,000 Indonesians living in Australia in the late 1990s are ethnic Chinese, and they have since merged with other Chinese communities.[106] In New Zealand, many migrants reside in the suburbs of Auckland after some 1,500 sought asylum from the 1998 upheaval, of which two-thirds were granted residency.[107]

Australian scholar Charles Coppel believes Chinese Indonesian migrants also constitute a large majority of returned overseas Chinese living in Hong Kong. Though it is impossible to accurately count this number, news sources have provided estimates ranging from 100,000 to 150,000,[lower-alpha 5] while the estimate of 150,000 was published in the Hong Kong Standard on 21 December 1984. (Coppel 2002, p. 356).

Of the 57,000 Indonesians living in the United States in 2000, one-third were estimated to be ethnic Chinese.[108] Locally knowledgeable migrants in Southern California estimate that 60 percent of Indonesian Americans living in the area are of Chinese descent. [109] In Canada, only a minority of the emigrant Chinese Indonesian community speak Chinese. Although families are interested in rediscovering their ethnic traditions, their Canadian-born children are often reluctant to learn either Chinese mother tongue.[110]

Society

It may be stated as a general rule that if a given area of Indonesia was settled by Chinese in appreciable numbers prior to this [20th] century, Chinese society there is in some degree dichotomous today. In one sector of the society, adults as well as children are Indonesia-born, the orientation toward China is attenuated, and the influence of the individual culture is apparent. In the other sector of the society, the population consists of twentieth-century immigrants and their immediate descendants, who are less acculturated and more strongly oriented toward China. The significance and pervasiveness of the social line between the two sectors varies from one part of Indonesia to another.

— G. William Skinner, "The Chinese Minority", Indonesia pp. 103–104

Scholars who study Chinese Indonesians often distinguish members of the group according to their racial and sociocultural background: the "totok" and the "peranakan". The two terms were initially used to racially distinguish the pure-blooded Chinese from those with mixed ancestry. A secondary meaning to the terms later arose that meant the "totok" were born in China and anyone born in Indonesia was considered "peranakan".[lower-alpha 6] Segmentation within "totok" communities occurs through division in speech groups, a pattern that has become less apparent since the turn of the 20th century. Among the indigenized "peranakan" segmentation occurs through social class, which is graded according to education and family standing rather than wealth.[112]

Gender and kinship

Kinship structure in the "totok" community follows the patrilineal, patrilocal, and patriarchal traditions of Chinese society, a practice which has lost emphasis in "peranakan" familial relationships. Instead, kinship patterns in indigenized families have incorporated elements of matrilocal, matrilineal, and matrifocal traditions found in Javanese society. Within this community, both sons and daughters can inherit the family fortune, including ancestral tablets and ashes.[113] Political, social, and economic authority in "peranakan" families is more evenly distributed between the two genders than in "totok" families. Kin terms do not distinguish between maternal and paternal relatives and polygyny is strongly frowned upon. Western influence in "peranakan" society is evidenced by the high proportion of childless couples. Those who did have children also had fewer of them than "totok" couples.[114]

Despite their break from traditional kinship patterns, "peranakan" families are closer to some traditional Chinese values than the "totok". Because the indigenized population have lost much of the connection to their ancestral homes in the coastal provinces of China, they are less affected by the 20th-century modernization patterns that transformed the region. The "peranakan" have a stricter attitude toward divorce, though the separation rates among families in both segments are generally lower than other ethnic groups. Arranged marriages are more common in "peranakan" families, whose relationships tend to be more nepotistic. Secularization among the "totok" meant that their counterparts carry out ancestral rituals to a higher degree, and "peranakan" youth tend to be more religious. Through education provided by high-quality Catholic and Protestant schools, these youth are much more likely to convert to Christianity.[115]

In the 21st century, the conceptual differences of "totok" and "peranakan" Chinese are slowly becoming outdated as some families show a mixture of characteristics from both cultures.[116] Interracial marriage and cultural assimilation often prevent the formation a precise definition of Chinese Indonesians in line with any simple racial criterion. Use of a Chinese surname, in some form or circumstance, is generally a sign of cultural self-identification as ethnic Chinese or alignment with a Chinese social system.[85]

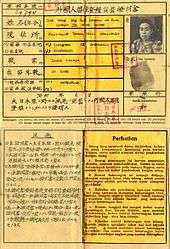

Identity

Ethnic Chinese in the 1930 Dutch East Indies census were categorized as foreign orientals, which led to separate registration.[95] Citizenship was conferred upon the ethnic Chinese through a 1946 citizenship act after Indonesia became independent, and it was further reaffirmed in 1949 and 1958. However, they often encountered obstacles regarding the legality of their citizenship. Chinese Indonesians were required to produce an Indonesian Citizenship Certificate (Surat Bukti Kewarganegaraan Republik Indonesia, SBKRI) when conducting business with government officials.[117] Without the SBKRI, they were not able to make passports and identity cards (Kartu Tanda Penduduk, KTP); register birth, death, and marriage certificates; or register a business license.[118] The requirement for its use was abolished in 1996 through a presidential instruction which was reaffirmed in 1999, but media sources reported that local authorities were still demanding the SBKRI from Chinese Indonesians after the instructions went into effect.[77]

Other terms used for identifying sectors of the community include peranakan and totok. The former, traditionally used to describe those born locally, is derived from the root Indonesian word anak ("child") and thus means "child of the land". The latter is derived from Javanese, meaning "new" or "pure", and is used to describe the foreign born and new immigrants.[119] A significant number of Chinese Indonesians also live in the People's Republic of China and Hong Kong; they are considered part of the population of "returned overseas Chinese" (歸 國 華僑).[55] To identify the varying sectors of Chinese Indonesian society, Tan contends they must be differentiated according to nationality into those who are citizens of the host country and those who are resident aliens, then further broken down according to their cultural orientation and social identification.[120] In her doctoral dissertation, Aimee Dawis notes that such definitions, based on cultural affinity and not nation of origin, have gained currency since the early 1990s, although the old definition is occasionally used.[121]

Sociologist Mely G. Tan asserts that scholars studying ethnic Chinese emigrants often refer to the group as a "monolithic entity": the overseas Chinese.[120] Such treatment also persists in Indonesia; a majority of the population referred to them as orang Cina or orang Tionghoa (both meaning "Chinese people", 中華 人), or hoakiau (華僑).[lower-alpha 7] They were previously described in ethnographic literature as the Indonesian Chinese, but there has been a shift in terminology as the old description emphasizes the group's Chinese origins, while the more recent one, its Indonesian integration.[122] Aimee Dawis, citing prominent scholar Leo Suryadinata, believes the shift is "necessary to debunk the stereotype that they are an exclusive group" and also "promotes a sense of nationalism" among them.[123]

Economic aptitude

Members of the "totok" community are more inclined to be entrepreneurs and adhere to the practice of guanxi, which is based on the idea that one's existence is influenced by the connection to others, implying the importance of business connections.[124] In the first decade following Indonesian independence their business standing strengthened after being limited to small businesses in the colonial period. By the 1950s virtually all retail stores in Indonesia were owned by ethnic Chinese entrepreneurs, whose businesses ranged from selling groceries to construction material. Discontentment soon grew among indigenous merchants who felt unable to compete with ethnic Chinese businesses.[125] Under pressure from indigenous merchants, the government enacted the Benteng program and Presidential Regulation 10 of 1959, which imposed restrictions on ethnic Chinese importers and rural retailers. Ethnic Chinese businesses persisted, owing to their integration into larger networks throughout Southeast Asia, and their dominance continued despite continuous state and private efforts to encourage the growth of indigenous capital.[126] Indonesian Chinese businesses are part of the larger bamboo network, a network of overseas Chinese businesses operating in the markets of Southeast Asia that share common family and cultural ties.[127]

Government policies shifted dramatically after 1965, becoming more favorable to economic expansion. In an effort to rehabilitate the economy, the government turned to those who possessed the capability to invest and expand corporate activity. Ethnic Chinese capitalists, called the cukong, were supported by the military, which emerged as the dominant political force after 1965.[126] Indigenous businessmen once again demanded greater investment support from the government in the 1970s, but legislative efforts failed to reduce ethnic Chinese dominance.[128] In a 1995 study published by the East Asia Analytical Unit of Australia's Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, approximately 73 percent of the market capitalization value of publicly listed companies (excluding foreign and state-owned companies) were owned by Chinese Indonesians. Additionally, they owned 68 percent of the top 300 conglomerates and nine of the top ten private sector groups at the end of 1993.[129] This figure propagated the general belief that ethnic Chinese—then estimated at 3 percent of the population—controlled 70 percent of the economy.[130][131][132] Although the accuracy of this figure was disputed, it was evident that a wealth disparity existed along ethnic boundaries. The image of an economically powerful ethnic Chinese community was further fostered by the government through its inability to dissociate itself from the patronage networks.[133] The Hokchia group dominated the ethnic Chinese business scene during the Suharto government, although other groups emerged after 1998.[57]

The top five conglomerates in Indonesia prior to the 1997 Asian financial crisis—the Salim Group, Astra International, the Sinar Mas Group, Gudang Garam, Sampoerna and the Lippo Group—were all owned by ethnic Chinese, with annual sales totaling Rp112 trillion (US$47 billion).[134] When the crisis finally hit the country, the rupiah's plunge severely disrupted corporate operations. Numerous conglomerates lost a majority of their assets and collapsed. Over the next several years, other conglomerates struggled to repay international and domestic debts.[135] Reforms introduced following 1998 were meant to steer the economy away from oligarchic arrangements established under the New Order;[136] however, plans for reform proved too optimistic. When President B. J. Habibie announced in a 19 July 1998 interview with The Washington Post that Indonesia was not dependent on ethnic Chinese businessmen, the rupiah's value plunged 5 percent.[lower-alpha 8] This unexpected reaction prompted immediate changes in policies, and Habibie soon began enticing conglomerates for their support in the reform plans.[137] Most were initially fearful of democratization, but the process of social demarginalization meant that the ethnic Chinese were regarded as equal members of society for the first time in the nation's history.[138][139] Increased regional autonomy allowed surviving conglomerates to explore new opportunities in the outer provinces, and economic reforms created a freer market.[140]

Political activity

Between the 18th and early 20th centuries, ethnic Chinese communities were dominated by the "peranakan" presence.[141] This period was followed by the growth of "totok" society. As part of a resinicization effort by the indigenized ethnic Chinese community, a new pan-Chinese movement emerged with the goal of a unified Chinese political identity. The movement later split in the 1920s when "peranakan" elites resisted the leadership of the "totok" in the nationalist movement, and the two groups developed their own objectives.[142] When it became apparent that unification was being achieved on "totok" terms, "peranakan" leaders chose to align their community with the Dutch, who had abandoned the segregation policies in 1908. The two communities once again found common ground in opposition to the invading Japanese when the occupying forces treated all Chinese groups with contempt.[143]

The issue of nationality, following independence, politicized the ethnic Chinese and led to the formation of Baperki in 1954, as the first and largest Chinese Indonesian mass organization. Baperki and its majority "peranakan" membership led the opposition against a draft law that would have restricted the number of ethnic Chinese who could gain Indonesian citizenship. This movement was met by the Islamic Masyumi Party in 1956 when it called for the implementation of affirmative action for indigenous businesses.[52] During the 1955 legislative election, Baperki received 178,887 votes and gained a seat on the People's Representative Council (DPR). Later that year, two Baperki candidates were also elected to the Constitutional Assembly.[144]

Ethnic-based political parties were banned under the government of President Suharto, leaving only the three indigenous-dominated parties of Golkar, the United Development Party (PPP), and the Indonesian Democratic Party (PDI). The depoliticizing of Indonesian society confined ethnic Chinese activities to the economic sector. Chinese Indonesian critics of the regime were mostly "peranakan" and projected themselves as Indonesians, leaving the ethnic Chinese with no visible leaders.[144] On the eve of the 1999 legislative election, after Suharto's resignation, the news magazine Tempo conducted a survey of likely Chinese Indonesian voters on their political party of choice for the election. Although respondents were able to choose more than one party, 70 percent favored the Indonesian Democratic Party – Struggle (PDI–P), whose image of a nationalist party was considered favorable toward the ethnic Chinese. The party also benefited from the presence of economist Kwik Kian Gie, who was well respected by both ethnic Chinese and non-ethnic-Chinese voters.[145]

New ethnic political parties such as the Chinese Indonesian Reform Party (Partai Reformasi Tionghoa Indonesia, PARTI) and the Indonesian Bhinneka Tunggal Ika Party (Partai Bhinneka Tunggal Ika Indonesia, PBI) failed to garner much support in the 1999 election. Despite this result, the number of Chinese Indonesian candidates standing in national election increased from fewer than 50 in 1999 to almost 150 in 2004.[146] Of the 58 candidates of Chinese descent who ran for office as representatives from Jakarta in the 2009 legislative election, two won seats.[147]

Culture

Language

Four major Chinese-speech groups are represented in Indonesia: Hokkien (Southern Min; Min Nan), Mandarin, Hakka and Cantonese. In addition to these, the Teochew people speak their own dialect that has some degree of mutual intelligibility with Hokkien. Distinctions between the two, however, are accentuated outside of their regions of origin.[87] There were an estimated 2.2 million native speakers of various Chinese varieties in Indonesia in 1982: 1,300,000 speakers of Southern Min varieties (including Hokkien and Teochew); 640,000 Hakka speakers; 460,000 Mandarin speakers; 180,000 Cantonese speakers; and 20,000 speakers of the Eastern Min varieties (including Fuzhou dialect). Additionally, an estimated 20,000 spoke different dialects of the Indonesian language.[148]

Many of the Chinese living in capital city Jakarta and other towns located in Java are not fluent in Chinese languages, due to New Order's banning of Chinese languages, but those who are living in non-Java cities especially in Sumatra and Kalimantan can speak Chinese and its dialects fluently. The Chinese along the North-Eastern coast of Sumatra, especially in North Sumatra, Riau, Riau Islands and Jambi are predominantly Hokkien (Min Nan) speakers, and there are also two different variants of Hokkien being used, such as Medan Hokkien, which is based on the Zhangzhou dialect, and Riau Hokkien, which is based on the Quanzhou dialect. There are also Hokkien speakers in Java (Semarang, Surakarta etc.), Sulawesi and Kalimantan (Borneo). Meanwhile, the Hakkas are the majority in Aceh, Bangka-Belitung and north region in West Kalimantan like Singkawang, Pemangkat and Mempawah, several Hakka communities also live in parts of Java especially in Tangerang and Jakarta. The Cantonese peoples mainly living in big cities like Jakarta, Medan, Batam, Surabaya, Pontianak and Manado. The Teochew people are the majority within Chinese community in West Kalimantan, especially in Central to Southern areas such as Ketapang, Kendawangan, and Pontianak, as well as in the Riau Islands, which include Batam and Karimun. There are sizable communities of Hokchia or Foochownese speakers in East Java, especially in Surabaya. The Hainanese people can also found in Pematangsiantar in North Sumatra.

Many Indonesians, including the ethnic Chinese, believe in the existence of a dialect of the Malay language, Chinese Malay, known locally as Melayu Tionghoa or Melayu Cina. The growth of "peranakan" literature in the second half of the 19th century gave rise to such a variant, popularized through silat (martial arts) stories translated from Chinese or written in Malay and Indonesian. However, scholars argue it is different from the mixture of spoken Javanese and Malay that is perceived to be "spoken exclusively by ethnic Chinese".[lower-alpha 9]

[E]xcept for a few loan words from Chinese, nothing about 'Chinese Malay' is uniquely Chinese. The language was simply low, bazaar Malay, the common tongue of Java's streets and markets, especially of its cities, spoken by all ethnic groups in the urban and multi-ethnic environment. Because Chinese were a dominant element in the cities and markets, the language was associated with them, but government officials, Eurasians, migrant traders, or people from different language areas, all resorted to this form of Malay to communicate.

— Mary Somers Heidhues, The Encyclopedia of the Chinese Overseas[149]

Academic literature discussing Chinese Malay commonly note that ethnic Chinese do not speak the same dialect of Malay throughout the archipelago.[150] Furthermore, although the Dutch colonial government first introduced the Malay orthography in 1901, Chinese newspapers did not follow this standard until after independence.[151] Because of these factors, the ethnic Chinese play a "significant role" in the development of the modern Indonesian language as the largest group during the colonial period to communicate in a variety of Malay dialects.[152]

By 2018 the numbers of Chinese Indonesians studying Standard Mandarin increased.[153]

Literature

Chinese cultural influences can be seen in local Chinese Malay literature, which dates back to the late 19th century. One of the earliest and most comprehensive works on this subject, Claudine Salmon's 1981 book Literature in Malay by the Chinese of Indonesia: A Provisional Annotated Bibliography, lists over 3,000 works. Samples of this literature were also published in a six-volume collection titled Kesastraan Melayu Tionghoa dan Kebangsaan Indonesia ("Chinese Malay Literature and the Indonesian Nation").[118]

Kho Ping Hoo or Asmaraman Sukowati Kho Ping Hoo is a beloved Indonesian author of Chinese ethnicity. He is well known in Indonesia for his martial art fiction set in the background of China or Java. During his 30 years career, at least 120 stories has been published (according to Leo Suryadinata). However, Forum magazine claimed at least Kho Ping Hoo had 400 stories with the background of China and 50 stories with the background of Java.

Media

All Chinese-language publications were prohibited under the assimilation policy of the Suharto period, with the exception of the government-controlled daily newspaper Harian Indonesia.[154] The lifting of the Chinese-language ban after 1998 prompted the older generation of Chinese Indonesians to promote its use to the younger generation; according to Malaysian-Chinese researcher of the Chinese diaspora, Chang-Yau Hoon, they believed they would "be influenced by the virtues of Chinese culture and Confucian values".[155] One debate took place in the media in 2003, discussing the Chinese "mu yu" (母語, "mother tongue") and the Indonesian "guo yu" (國語, "national language").[155] Nostalgia was a common theme in the Chinese-language press in the period immediately following Suharto's government. The rise of China's political and economic standing at the turn of the 21st century became an impetus for their attempt to attract younger readers who seek to rediscover their cultural roots.[156]

During the first three decades of the 20th century, ethnic Chinese owned most, if not all, movie theaters in cities throughout the Dutch East Indies. Films from China were being imported by the 1920s, and a film industry began to emerge in 1928 with the arrival of the three Wong brothers from Shanghai—their films would dominate the market through the 1930s.[157] These earliest films almost exclusively focused on the ethnic Chinese community, although a few examined inter-ethnic relations as a main theme.[158] The later ban on the public use of Chinese language meant that imported films and television programs were required to be dubbed in English with subtitles in Indonesian. When martial arts serials began appearing on national television in 1988, they were dubbed in Indonesian. One exception was the showing of films from Hong Kong in Chinese—limited to ethnic Chinese districts and their surroundings—because of an agreement between importers and the film censor board.[159]

Religion

Religion of Chinese Indonesians (2010 census)[160]

There is little scholarly work devoted to the religious life of Chinese Indonesians. The 1977 French book Les Chinois de Jakarta: Temples et Vie Collective ("The Chinese of Jakarta: Temples and Collective Life") is the only major study to assess ethnic Chinese religious life in Indonesia.[161] The Ministry of Religious Affairs grants official status to six religions: Islam, Protestantism, Catholicism, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Confucianism. A 2006 civil registration law does not allow Indonesians to identify themselves as a member of any other religion on their identity cards.[162]

According to an analysis of the 2000 census data, about half of Chinese Indonesians were Buddhist, and about one third Protestant or Catholic.[163] A New York Times report however, puts the percentage of Christians much higher, at over 70 percent.[164] With the exception of Chinese-Filipinos, Chinese Indonesians tend to be more Christian than other Chinese ethnic groups of Southeast Asia due to a complex of historical reasons. Throughout the 20th century Chinese religion and culture was forbidden and persecuted in Indonesia, forcing many Chinese to convert to Christianity.[165] The first wave of conversions occurred in the 1950s and 1960s, and the number of ethnic Chinese Christians during this period quadrupled. The second wave followed after the government withdrew Confucianism's status as a recognized religion in the 1970s. Suharto endorsed a systematic campaign of eradication of Confucianism.[165] As the result, many Chinese in Jakarta and other parts in Java island are mostly Christian, meanwhile in non-Java cities like Medan, Pontianak and other parts in Sumatra and Borneo island are still adherent to Buddhism, and some of them still practising Taoism, Confucianism and other traditional Chinese belief.[166]

In a country where nearly 90 percent of the population are Muslims, the ethnic Chinese Muslims form a small minority of the ethnic Chinese population, mainly due to intermarriages between Chinese men and local Muslim women. The 2010 census reckoned that 4.7% of Chinese Indonesians were followers of Islam.[160] Associations such as the Organization of Chinese Muslims of Indonesia (Persatuan Islam Tionghoa Indonesia, PITI) had been in existence in the late 19th century. PITI was re-established in 1963 as a modern organization, but occasionally experienced periods of inactivity.[167] The Supreme Council for the Confucian Religion in Indonesia (Majelis Tinggi Agama Khonghucu Indonesia, MATAKIN) estimated that 95 percent of Confucians are ethnic Chinese; most of the remaining 5 percent are ethnic Javanese converts.[162] Although the government has restored Confucianism's status as a recognized religion, many local authorities do not abide by it and have refused to allow ethnic Chinese from listing it as a religion on their identity cards.[168] Local officials remained largely unaware that the civil registration law legally allowed citizens to leave the religion section on their identity cards blank.[162]

Vihara Eka Dharma Manggala, a Buddhist Temple in Samarinda, East Kalimantan

Vihara Eka Dharma Manggala, a Buddhist Temple in Samarinda, East Kalimantan Geredja Keristen Tionghoa or Chinese Christian Church in Jakarta, c.1952

Geredja Keristen Tionghoa or Chinese Christian Church in Jakarta, c.1952

Kong Miao Confucian Temple in Taman Mini Indonesia Indah, Jakarta

Kong Miao Confucian Temple in Taman Mini Indonesia Indah, Jakarta

Architecture

Various forms of Chinese architecture exist throughout Indonesia with marked differences between urban and rural areas and among the different islands.[169] Architectural developments by the Chinese in Southeast Asia differ from those in mainland China. By blending local and European (Dutch) design patterns, numerous variations of fusion styles emerged.[170] Chinese architecture in Indonesia has manifested in three forms: religious temples, study halls, and houses.[169] Cities during the colonial period were divided into three racial districts: European, oriental (Arabs, Chinese, and other Asians), and indigenous. There usually were no physical boundaries among the zones, except for rivers, walls, or roads in some cases. Such legal boundaries promoted high growths in urban density within each zone, especially in the Chinese quarters, often leading to poor environmental conditions.[171]

Early settlers did not adhere to traditional architectural practices when constructing houses, but instead adapted to living conditions in Indonesia. Although the earliest houses are no longer standing, they were likely built from wood or bamboo with thatched roofs, resembling indigenous houses found throughout Sumatra, Borneo, and Java. More permanent constructions replaced these settlements in the 19th century.[172] Segregation policies under the Dutch forbade the use of European architectural styles by non-European ethnic groups. The ethnic Chinese and other foreign and indigenous groups lived according to their own cultures. Chinese houses along the north coast of Java were renovated to include Chinese ornamentation.[173] As racial segregation eased at the turn of the 20th century, the ethnic Chinese who had lost their identity embraced European culture and began removing ethnic ornaments from their buildings. The policies implemented by the New Order government which prohibited the public display of Chinese culture have also accelerated the transition toward local and Western architecture.[174]

Cuisine

| Loanword | Chinese | English name |

|---|---|---|

| angciu | 料酒 | cooking wine |

| mi | 麵 | noodles |

| bakmi | 肉麵 | egg noodles with meat |

| bakso | 肉酥 | meatball |

| tahu | 豆腐 | tofu |

| bakpao | 肉包 | meat bun |

| tauco | 豆醬 | fermented soybeans sauce |

| kwetiau | 粿條 | rice noodles |

| bihun/mihun | 米粉 | rice vermicelli |

| juhi and cumi | 魷魚 | cuttlefish |

| lobak | 蘿蔔 | radish or turnip |

| kue | 粿 | cookie, pastry |

| kuaci | 瓜籽 | melon seed |

| Source: Tan 2002, p. 158 | ||

Chinese culinary culture is particularly evident in Indonesian cuisine through the Hokkien, Hakka, and Cantonese loanwords used for various dishes.[175] Words beginning with bak (肉) signify the presence of meat, e.g. bakpao ("meat bun"); words ending with cai (菜) signify vegetables, e.g. pecai ("Chinese white cabbage") and capcai.[176] The words mi (麵) signify noodle as in mie goreng.

Most of these loanwords for food dishes and their ingredients are Hokkien in origin, and are used throughout the Indonesian language and vernacular speech of large cities. Because they have become an integral part of the local language, many Indonesians and ethnic Chinese do not recognize their Hokkien origins. Some popular Indonesian dishes such as nasi goreng, lumpia, and bakpia can trace their origin to Chinese influence. Some food and ingredients are part of the daily diet of both the indigenous and ethnic Chinese populations as side dishes to accompany rice, the staple food of most of the country.[177] Among ethnic Chinese families, both peranakan and totok, pork is generally preferred as meat;[178] this is in contrast with traditional Indonesian cuisine, which in majority-Muslim areas avoids the meat. The consumption of pork has, however, decreased in recent years owing to a recognition of its contribution to health hazards such as high cholesterol levels and heart disease.[177]

In a 1997 restaurant listing published by the English-language daily The Jakarta Post, which largely caters to expatriates and middle class Indonesians, at least 80 locations within the city can be considered Chinese out of the 10-page list. Additionally, major hotels generally operate one or two Chinese restaurants, and many more can be found in large shopping centers.[179] Upscale Chinese restaurants in Jakarta, where the urban character of the ethnic Chinese is well established, can be found serving delicacies such as shark fin soup and bird's nest soup.[175] Food considered to have healing properties, including ingredients in traditional Chinese medicine, are in high demand.[180]

Education

Citizens of the Republic of China (Taiwan) residing in Indonesia are served by two international schools:[181] Jakarta Taipei School (雅加達臺灣學校), which was the first Chinese-language school in Indonesia since the Indonesian government ended its ban on the Chinese language,[182] and the Surabaya Taipei International School (印尼泗水臺灣學校).[181]

Popular Culture

Geography

Warung Buncit is name of an area in South Jakarta (also known as Jalan AH Nasution) that took its origin from Chinese Indonesian profile name Bun Tjit. Zaenuddin HM wrote in his book "212 Asal-Usul Djakarta Tempo Doeloe"[183] that the name was inspired by a local shop (Warung in Indonesian language) ran by a Chinese Indonesia name Bun Tjit (styled Buncit). The shop was so famous among the local that the locals began to call the area Warung Buncit (Buncit's Shop). The area had been known as Warung Buncit ever since.

See also

- Benteng Chinese

- The Chinese in Indonesia, a book by Pramoedya Ananta Toer

- Indonesian Americans

- Indonesian Australians

- Legislation on Chinese Indonesians

- List of Chinese Indonesians

- People's Republic of China – Indonesia relations

Notes

- According to Heidhues (2001, p. 179), the length of the leases depended on the location. Bangka had 25-year leases, while several areas offered 50-year leases.

- Purdey (2006, p. 14) writes that, as ethnic Chinese constituted two percent of Indonesia's population at the time, a similar number of Chinese Indonesians may have been killed in the purges. She qualifies this, however, by noting that most of the killings were in rural areas, while the Chinese were concentrated in the cities.

- Suharto's government had banned Mandarin-language schools in July 1966 (Tan 2008, p. 10). Mandarin-language press and writings were severely limited that year. (Setiono 2003, p. 1091) According to Tan (2008, p. 11), many families taught Mandarin to their children in secret.

- Suryadinata, Arifin & Ananta (2003, p. 77) used the 31 published volumes of data on the 2000 census and reported 1,738,936 ethnic Chinese citizens, but this figure did not include their population in 19 provinces. Space restrictions in the census publication limited the ethnic groups listed for each province to the eight largest. Ananta, Arifin & Bakhtiar (2008, p. 23) improved upon this figure by calculating directly from the raw census data.

- The estimate of 100,000 was published in Asiaweek on 3 June 1983

- Dawis (2009, p. 77) cited a presentation by Charles Coppel at the 29th International Congress of Orientalists for information on the initial usage of the two terms. Skinner (1963, pp. 105–106) further noted that totok is an Indonesian term specifically for foreign-born immigrants but is extended to include the descendants oriented toward their country of origin. Peranakan, on the other hand, means "children of the Indies".

- The latter two terms are derived from the Hokkien Chinese. Sociologist Mely G. Tan argued that these terms "only apply to those who are alien, not of mixed ancestry, and who initially do not plan to stay in Indonesia permanently" (Kahin 1991, p. 119). She also noted that the terms Cina (Tjina in older orthography) and Cino (Tjino) carry a derogatory meaning to earlier generations of immigrants, especially those living on the island of Java. Dawis (2009, p. 75) noted this connotation appears to have faded in later generations.

- Habibie said in the interview, "If the Chinese community doesn't come back because they don't trust their own country and society, I cannot force [them], nobody can force them. [...] Do you really think that we will then die? Their place will be taken over by others." (Suryadinata 1999, p. 9).

- Indonesian scholar Dede Oetomo believed "the term 'Chinese Malay' is really a misnomer. There may be a continuity between 'Chinese Malay' and modern Indonesian, especially because the former was also used in the written discourse of members of ethnic groups besides the Chinese in the colonial period and well into the postindependence era" (Kahin 1991, p. 54).

References

- Kewarganegaraan, Suku Bangsa, Agama dan Bahasa Sehari-hari Penduduk Indonesia Hasil Sensus Penduduk 2010. Badan Pusat Statistik. 2011. ISBN 9789790644175. Archived from the original on 10 July 2017.

- Thomas Fuller (12 December 1998). "Indonesia's Ethnic Chinese Find a Haven For Now, But Their Future Is Uncertain: Malaysia's Wary Welcome". International Herald Tribune. The New York Times. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- Stephen Gapps. "A Complicated Journey: Chinese, Indonesian, and Australian Family Histories". Australian National Maritime Museum. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- Terri McCormack (2008). "Indonesians". Dictionary of Sydney. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- "Statistics" (in Chinese). National Immigration Agency, ROC. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- Wang Gungwu, 'Sojourning: the Chinese experience in Southeast Asia', in Anthony Reid, ed., Sojourners and settlers: histories of Southeast Asia and the Chinese Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 1996, pp.1-9.

- Suryadinata, Arifin & Ananta 2003, p. 74.

- Hoon 2006, p. 96.

- Joe Cochrane (22 November 2014). "An Ethnic Chinese Christian, Breaking Barriers in Indonesia". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- Cunningham 2008, p. 104.

- C. Fasseur, ‘Cornerstone and Stumbling Block: Racial Classification and the Late Colonial State in Indonesia’, in Robert Cribb (ed.), The Late Colonial State in Indonesia: political and economic foundations of the Netherlands Indies, 1880-1942 (Leiden: KITLV, 1994), pp. 31-56.

- Reid 2001, p. 17.

- Ma 2005, p. 115.

- Tan 2005, p. 796.

- Reid 1999, p. 52.

- Reid 2001, p. 33.

- Guillot, Lombard & Ptak 1998, p. 179.

- Borschberg 2004, p. 12.

- Heidhues 1999, p. 152.

- Phoa 1992, p. 9.

- Phoa 1992, p. 7.

- Leonard Blusse and Chen Menghong, "Introduction", in Leonard Blusse and Chen Menghong, The Archives of the Kong Koan of Batavia (Leiden: Brill, 2003), pp. 1-3.

- Glionna, John M. (4 July 2010). "In Indonesia, 1998 violence against ethnic Chinese remains unaddressed". Los Angeles Times. Jakarta, Indonesia.

- Phoa 1992, p. 8.

- Phoa 1992, p. 10.

- Reid 2007, pp. 44–47.

- Setiono 2003, pp. 125–137.

- Hellwig & Tagliacozzo 2009, p. 168.

- Keat Gin Ooi (2004). Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor. ABC-CLIO. pp. 1057–. ISBN 978-1-57607-770-2.

- Anthony Reid; Kristine Alilunas-Rodgers (1996). Sojourners and Settlers: Histories of Southeast China and the Chinese. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 75–. ISBN 978-0-8248-2446-4.

- Willem G. J. Remmelink (1990). Emperor Pakubuwana II, Priyayi & Company and the Chinese War. W.G.J. Remmelink. p. 136.

- Willem G. J. Remmelink (1994). The Chinese war and the collapse of the Javanese state, 1725-1743. KITLV Press. p. 136. ISBN 978-90-6718-067-2.

- Phoa 1992, p. 11.

- Phoa 1992, p. 12.