Gaelic football

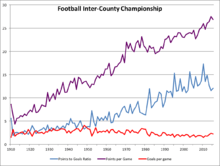

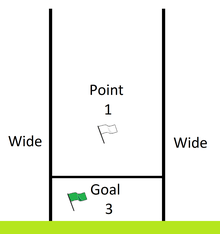

Gaelic football (Irish: Peil Ghaelach; short name Peil[1] or Caid), commonly referred to as football or Gaelic,[2] is an Irish team sport. It is played between two teams of 15 players on a rectangular grass pitch. The objective of the sport is to score by kicking or punching the ball into the other team's goals (3 points) or between two upright posts above the goals and over a crossbar 2.5 metres (8.2 ft) above the ground (1 point).

Aidan O'Mahony of 2009 National Football League | |

| Highest governing body | Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) |

|---|---|

| Nicknames | Caid Football Gaelic Gaa |

| First played | 1885 |

| Clubs | More than 2,500 |

| Characteristics | |

| Contact | Limited |

| Team members | |

| Mixed gender | No |

| Type | Outdoor |

| Equipment | Gaelic football |

| Venue | Gaelic games field |

| Presence | |

| Olympic | 1904 (demonstration sport) |

| Paralympic | No |

Players advance the football, a spherical leather ball resembling a volleyball, up the field with a combination of carrying, bouncing, kicking, hand-passing, and soloing (dropping the ball and then toe-kicking the ball upward into the hands). In the game, two types of scores are possible: points and goals. A point is awarded for kicking or hand-passing the ball over the crossbar, signalled by the umpire raising a white flag. A goal is awarded for kicking the ball under the crossbar into the net, signalled by the umpire raising a green flag. Positions in Gaelic football are similar to those in other football codes, and comprise one goalkeeper, six backs, two midfielders, and six forwards, with a variable number of substitutes.

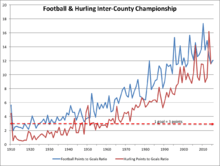

Gaelic football is one of four sports (collectively referred to as the "Gaelic games") controlled by the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA), the largest sporting organisation in Ireland. Along with hurling and camogie, Gaelic football is one of the few remaining strictly amateur sports in the world, with players, coaches, and managers prohibited from receiving any form of payment. Gaelic football is mainly played on the island of Ireland, although units of the Association exist in Great Britain, North America and Australia.

The final of the All-Ireland Senior Championship, held annually at Croke Park, Dublin, draws crowds of more than 80,000 people. Outside Ireland, football is mainly played among members of the Irish diaspora. Gaelic Park in New York City is the largest purpose-built Gaelic sports venue outside Ireland. Three major football competitions operate throughout the year: the National Football League and the All-Ireland Senior Championship operate on an inter-county basis, while the All-Ireland Club Championship is contested by individual clubs. The All-Ireland Senior Championship is considered the most prestigious event in Gaelic football.

Under the auspices of the GAA, Gaelic football is a male-only sport; however, the related sport of ladies' Gaelic football is governed by the Ladies' Gaelic Football Association. Similarities between Gaelic football and Australian rules football have allowed the development of international rules football, a hybrid sport, and a series of Test matches has been held regularly since 1998.

History

While Gaelic football as it is known today dates back to the late 19th century, various kinds of football were played in Ireland before this time. The first legal reference to football in Ireland was in 1308, when John McCrocan, a spectator at a football game at Novum Castrum de Leuan (the New Castle of the Lyons or Newcastle) was charged with accidentally stabbing a player named William Bernard. A field near Newcastle, South Dublin is still known as the football field.[3][4][5][6] The Statute of Galway of 1527 allowed the playing of "foot balle" and archery but banned "'hokie'—the hurling of a little ball with sticks or staves" as well as other sports.

By the 17th century, the situation had changed considerably. The games had grown in popularity and were widely played.[7] This was due to the patronage of the gentry. Now instead of opposing the games it was the gentry and the ruling class who were serving as patrons of the games. Games were organised between landlords with each team comprising 20 or more tenants. Wagers were commonplace with purses of up to 100 guineas (Prior, 1997).

The earliest record of a recognised precursor to the modern game date from a match in County Meath in 1670, in which catching and kicking the ball was permitted.[7]

However even "foot-ball" was banned[8] by the severe Sunday Observance Act of 1695, which imposed a fine of one shilling (a substantial amount at the time) for those caught playing sports. It proved difficult, if not impossible, for the authorities to enforce the Act and the earliest recorded inter-county match in Ireland was one between Louth and Meath, at Slane, in 1712, about which the poet James Dall McCuairt wrote a poem of 88 verses beginning "Ba haigeanta".

A six-a-side version was played in Dublin in the early 18th century, and 100 years later there were accounts of games played between County sides (Prior, 1997).

By the early 19th century, various football games, referred to collectively as caid, were popular in Kerry, especially the Dingle Peninsula. Father W. Ferris described two forms of caid: the "field game" in which the object was to put the ball through arch-like goals, formed from the boughs of two trees, and; the epic "cross-country game", which lasted the whole of a Sunday (after mass) and was won by taking the ball across a parish boundary. "Wrestling", "holding" opposing players, and carrying the ball were all allowed.

During the 1860s and 1870s, rugby football started to become popular in Ireland. Trinity College, Dublin was an early stronghold of rugby, and the rules of the (English) Football Association were codified in 1863 and distributed widely. By this time, according to Gaelic football historian Jack Mahon, even in the Irish countryside, caid had begun to give way to a "rough-and-tumble game", which even allowed tripping. Association football started to take hold, especially in Ulster, in the 1880s.

Limerick was the stronghold of the native game around this time, and the Commercials Club, founded by employees of Cannock's Drapery Store, was one of the first to impose a set of rules, which was adapted by other clubs in the city. Of all the Irish pastimes the GAA set out to preserve and promote, it is fair to say that Gaelic football was in the worst shape at the time of the association's foundation (GAA Museum, 2001).[7]

Irish forms of football were not formally arranged into an organised playing code by the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) until 1887. The GAA sought to promote traditional Irish sports, such as hurling and to reject "foreign" (particularly English) imports. The first Gaelic football rules, showing the influence of hurling and a desire to differentiate from association football—for example in their lack of an offside rule—were drawn up by Maurice Davin and published in the United Ireland magazine on 7 February 1887. The rules of the aforementioned Commercials Club became the basis for these official (Gaelic Football) rules who, unsurprisingly, won the inaugural All-Ireland Senior Football Final (representing County Limerick). The very first game of Gaelic Football under GAA rules (developed by Maurice Davin) was played near Callan, Co Kilkenny in February 1885.[9]

On Bloody Sunday in 1920, during the Anglo-Irish War, a football match at Croke Park was attacked by British forces. 14 people were killed and 65 were injured. Among the dead was Tipperary footballer Michael Hogan, for whom the Hogan Stand at Croke Park (completed in 1924) was named.

By 1958, Wembley Stadium hosted annual exhibition games of Gaelic football in England, before tens of thousands of spectators.[10]

Ladies' Gaelic football has become increasingly popular with women since the 1970s.

The relationship between Gaelic football and Australian rules football and the question of whether they have shared origins has been debated. What is known is that in 1967, Australian journalist, broadcaster and VFL umpire Harry Beitzel, inspired by watching the 1966 All-Ireland senior football final on television, sent an Australian team known as the "Galahs" including South Melbourne’s Bob Skilton, Richmond’s Royce Hart, Carlton’s Alex Jesaulenko and Melbourne and Carlton legend Ron Barassi as captain-coach – to play against Mayo and All-Ireland champions Meath, which was the first recorded major interaction between the two codes.

What then followed is the current International Rules Series between players of both codes and utilizing rules from both codes, which also gives them a chance to represent their country. The GAA chooses the team to represent Ireland, while the AFL chooses the team to represent Australia and has added a stipulation that each member of their team must have been named an All-Australian at least once. The two countries take turns hosting the series, and both countries' and sports' respective most prestigious venues – Croke Park and the Melbourne Cricket Ground (MCG) – have hosted series Tests. What is known as the Irish experiment also occurred, with Australian rules football clubs recruiting Gaelic football players. Irishmen who have distinguished themselves in both codes include Dublin's Jim Stynes – a 1984 minor All-Ireland football champion who became the 1991 Brownlow Medallist, a recipient of the Medal of the Order of Australia and a member of Melbourne's Team of the Century – and Kerry's Tadhg Kennelly, the first man to become both a senior All-Ireland football champion (2009) and an AFL Premiership player (2005 with Sydney, the Swans' first flag in 72 years).

Rules

Overview

Players advance the football, a spherical leather ball resembling a volleyball, up the field with a combination of carrying, bouncing, kicking, hand-passing, and soloing (dropping the ball and then toe-kicking the ball upward into the hands). In the game, two types of scores are possible: points and goals. A point is awarded for kicking or hand-passing the ball over the crossbar, signalled by the umpire raising a white flag. A goal is awarded for kicking the ball under the crossbar into the net, signalled by the umpire raising a green flag. Positions in Gaelic football are similar to that in other football codes, and comprise one goalkeeper, six backs, two midfielders, and six forwards, with a variable number of substitutes.

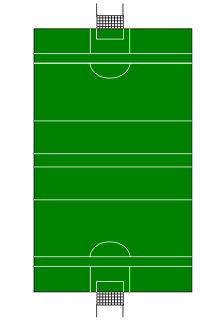

Playing field

A Gaelic pitch is similar in some respects to a rugby pitch but larger. The grass pitch is rectangular, stretching 130–145 metres (142–159 yards) long and 80–90 m (87–98 yd) wide. There are H-shaped goalposts at each end, formed by two posts, which are usually 6–7 metres (20–23 feet) high, set 6.5 m (21 ft) apart, and connected 2.5 m (8.2 ft) above the ground by a crossbar. A net extending behind the goal is attached to the crossbar and lower goal posts. The same pitch is used for hurling; the GAA, which organises both sports, decided this to facilitate dual usage. Lines are marked at distances of 13 metres (14 yd), 20 metres (22 yd), and 45 metres (49 yd) (65 metres or 71 yards in hurling) from each end-line. Shorter pitches and smaller goals are used by youth teams.[11]

Duration

The majority of adult football and all minor and under-21 matches last for 60 minutes, divided into two halves of 30 minutes, with the exception of senior inter-county games, which last for 70 minutes (two halves of 35 minutes). Draws are decided by replays or by playing 20 minutes of extra time (two halves of 10 minutes). Juniors have a half of 20 minutes or 25 minutes in some cases. Half-time lasts for about 5 or 10 minutes.

Teams

Teams consist of fifteen players[12] (a goalkeeper, two corner backs, a full back, two wing backs, a centre back, two mid fielders, two wing forwards, a centre forward, two corner forwards and a full forward) plus up to fifteen substitutes, of which six may be used. As for younger teams or teams that do not have enough players for fifteen-a-side, it is not uncommon to play thirteen-a-side (the same positions except without the full back and the full forward). Each player is numbered 1–15, starting with the goalkeeper, who must wear a jersey colour different from that of his or her teammates. Up to 15 substitutes may be named on the team sheet, number 16 usually being the reserve goalkeeper.

Positions

Ball

The game is played with a round leather football made of 18 stitched leather panels, similar in appearance to a traditional volleyball (but larger), with a circumference of 68–70 cm (27–28 in), weighing between 480–500 g (17–18 oz) when dry.[13] It may be kicked or hand passed. A hand pass is not a punch but rather a strike of the ball with the side of the closed fist, using the knuckle of the thumb.

Mark

In 2017, the GAA introduced the 'mark' across the board in Gaelic football. Similar to the mark in Australian rules football, a player who catches the ball from a kick-out is awarded a free kick. The rule in full states: "When a player catches the ball cleanly from a Kick-Out without it touching the ground, on or past the 45-metre (49 yd) line nearest the Kick Out point, he shall be awarded 'a Mark' by the Referee. The player awarded a 'Mark' shall have the options of (a) Taking a free kick or (b) Playing on immediately."[14] In comparison, the Australian rules equivalent requires the ball not to have touched the ground and for the kick to have travelled at least 15 metres (16 yd). In the experimental rules of 2019 a player can now also call a mark inside the opposition's 45-metre (49 yd) line after a clean catch from a kick played over 20 metres (22 yd) from outside the 45-metre (49 yd) line that doesn't touch the ground or any other player.[15]

In 2020, additional versions of the Mark came into force in gaelic football.[16] The Advanced Mark allowed a ball to be fielded cleanly inside the opposition 45, when kicked forward over a distance greater than 20 metres (22 yd) from outside the opposition 45. The referee is required to blow the whistle as this occurs, at which point the player has the option to take the Mark, or play-on.[16]

There is also a Defensive Mark, which a defender can get from a long-ball played into him.[16]

Types of fouls

There are three main types of fouls in Gaelic Football, which can result in the ball being given to the other team, a player being cautioned, a player being removed from the field, or even the game being terminated.

Technical fouls

The following are considered technical fouls ("fouling the ball"):

- Going five steps without releasing, bouncing or soloing the ball (soloing involves kicking the ball into one's own hands)[17]

- Bouncing the ball twice in a row (It may be soloed continuously)

- Changing hands: Throwing the ball between the hands (legal in the ladies' game)

- Throwing the ball (it may be "hand-passed" by striking with the fist).

- Hand passing a goal. To hand pass a ball with an open palm there must be a clear striking action (the ball may be punched over the bar from up in the air, but not into the goal).

- Picking the ball directly off the ground (it must be scooped up into the hands by the foot). However, in ladies' Gaelic football the ball may be picked up directly.

- Square ball is an often controversial rule: "If, at the moment the ball enters the small square, there is already an attacking player inside the small rectangle, then a free out is awarded." As of 2012 square balls are only counted if the player is inside the square when the ball is kicked from a free or set piece. An opposing player is allowed in the square during open play.

Aggressive fouls

Aggressive fouls are physical or verbal fouls committed by a player against an opponent or the referee. The player can be cautioned (shown a yellow card), ordered off the pitch without a substitute (red card),[18] or (as of 1 January 2014) ordered off the pitch with a substitution (black card).[19]

Dissent

A dissent foul is a foul where a player fails to comply with the officials' judgment and/or instructions. The player can be cautioned (shown a yellow card), ordered off the pitch without a substitute (red card), the free kick placement moved 13 m (14 yd) further down-field, or in certain circumstances, the game can be terminated. The following are considered dissent fouls:

- To challenge the authority of a referee, umpire, linesman or sideline official.

- To fail to comply with a referee's instruction to use an orifice guard.

- To refuse to leave the field of play, on the instruction of the referee, for attention, after an injury involving bleeding.

- To show dissent with the referee's decision to award a free kick to the opposing team.

- To refuse to leave the field of play when ordered off (red card) or rejoin the game after being ordered off.

- A team or player(s) leaving the field without the referee's permission or refusing to continue playing.[20]

Scoring

If the ball goes over the crossbar, a point is scored and a white flag is raised by an umpire. A point is scored by either kicking the ball over the crossbar, or fisting it over, in which case the hand must be closed while striking the ball. If the ball goes below the crossbar, a goal, worth three points, is scored, and a green flag is raised by an umpire. A goal is scored by kicking the ball into the net, not by fist passing the ball into it. However, a player can strike the ball into the net with a closed fist if the ball was played to him by another player or came in contact with the post/crossbar/ground prior to connection. The goal is guarded by a goalkeeper. Scores are recorded in the format Goal Total-Point Total. To determine the score-line goals must be converted to points and added to the other points. For example, in a match with a final score of Team A 0–21 Team B 4–8, Team A is the winner with 21 points, as Team B scored only 20 points (4 times 3, plus 8).

Tackling

The level of tackling allowed is less robust than in rugby.

Shoulder to shoulder contact and slapping the ball out of an opponent's hand are permitted, but the following are all fouls:

- Blocking a shot with the foot

- Pulling an opponent's jersey

- Pushing an opponent

- Sliding tackles

- Striking an opponent

- Touching the goalkeeper when he/she is inside the small rectangle

- Tripping

- Using both hands to tackle

- Wrestling the ball from an opponent's hands

Restarting play

- A match begins with the referee throwing the ball up between the four mid fielders.

- After an attacker has put the ball wide of the goals or scored a point or a goal, the goalkeeper may take a kick out from the ground at the 13-metre (14 yd) line. All players must be beyond the 20-metre (22 yd) line. However, in the 2019 experimental rules (rules tested in pre-season competitions), kick-outs must be taken from the 20-metre (22 yd) line.[15]

- After a defender has put the ball wide of the goals, an attacker may take a "45" from the ground on the 45-metre (49 yd) line, level with where the ball went wide.

- After a player has put the ball over the sideline, the other team may take a sideline kick at the point where the ball left the pitch. It may be kicked from the ground or the hands. The player who is taking the sideline kick must not pass the boundary line while taking.

- After a player has committed a foul, the other team may take a free kick (usually shortened to "free" in reports/commentaries) at the point where the foul was committed. It may be kicked from the ground or the hands.

- If a player has been fouled while passing the ball, the free may be taken from the point where the ball landed.

- After a defender has committed a foul inside the large rectangle, the other team may take a penalty kick from the ground from the centre of the 11-metre (12 yd) line. Only the goalkeeper may guard the goals.

- If many players are struggling for the ball and it is not clear who was fouled first, the referee may choose to throw the ball up between two opposing players.

Officials

A football match is overseen by up to eight officials:

- The referee

- Two linesmen

- Sideline official/Standby linesman (often referred to as "fourth official"; inter-county games only)

- Four umpires (two at each goal)

The referee is responsible for starting and stopping play, recording the score, awarding frees and booking and sending off players.

Linesmen are responsible for indicating the direction of line balls to the referee.

The fourth official is responsible for overseeing substitutions, and also indicating the amount of stoppage time (signalled to him by the referee) and the players substituted using an electronic board.

The umpires are responsible for judging the scoring. They indicate to the referee whether a shot was: wide (spread both arms), a 45-metre (49 yd) kick (raise one arm), a point (wave white flag), square ball (cross arms) or a goal (wave green flag). A disallowed score is indicated by crossing the green and white flags.

Other officials are not obliged to indicate any misdemeanours to the referee; they are only permitted to inform the referee of violent conduct they have witnessed that has occurred without the referee's knowledge. A linesman/umpire is not permitted to inform the referee of technical fouls such as a "double bounce" or an illegal pick-up of the ball. Such decisions can only be made at the discretion of the referee.

Team of the Century

The Team of the Century was nominated in 1984 by Sunday Independent readers and selected by a panel of experts including journalists and former players.[21] It was not chosen as part of the Gaelic Athletic Association's centenary year celebrations. The goal was to single out the best ever 15 players who had played the game in their respective positions. Naturally many of the selections were hotly debated by fans around the country.

| Goalkeeper | |||

| Dan O'Keeffe (Kerry) |

|||

| Right Corner Back | Full Back | Left Corner Back | |

| Enda Colleran (Galway) |

Paddy O'Brien (Meath) |

Seán Flanagan (Mayo) | |

| Right Half Back | Centre Back | Left Half Back | |

| Sean Murphy (Kerry) |

J. J. O'Reilly (Cavan) |

Stephen White (Louth) | |

| Midfield | |||

| Mick O'Connell (Kerry) |

Jack O'Shea (Kerry) | ||

| Right Half Forward | Centre Forward | Left Half Forward | |

| Seán O'Neill (Down) |

Seán Purcell (Galway) |

Pat Spillane (Kerry) | |

| Right Corner Forward | Full Forward | Left Corner Forward | |

| Mikey Sheehy (Kerry) |

Tommy Langan (Mayo) |

Kevin Heffernan (Dublin) |

Team of the Millennium

The Team of the Millennium was a team chosen in 1999 by a panel of GAA past presidents and journalists. The goal was to single out the best ever 15 players who had played the game in their respective positions, since the foundation of the GAA in 1884 up to the Millennium year, 2000. Naturally many of the selections were hotly debated by fans around the country.

| Goalkeeper | |||

| Dan O'Keeffe (Kerry) |

|||

| Right Corner Back | Full Back | Left Corner Back | |

| Enda Colleran (Galway) |

Joe Keohane (Kerry) |

Seán Flanagan (Mayo) | |

| Right Half Back | Centre Back | Left Half Back | |

| Seán Murphy (Kerry) |

John Joe O'Reilly (Cavan) |

Martin O'Connell (Meath) | |

| Midfield | |||

| Mick O'Connell (Kerry) |

Tommy Murphy (Laois) | ||

| Right Half Forward | Centre Forward | Left Half Forward | |

| Seán O'Neill (Down) |

Seán Purcell (Galway) |

Pat Spillane (Kerry) | |

| Right Corner Forward | Full Forward | Left Corner Forward | |

| Mikey Sheehy (Kerry) |

Tommy Langan (Mayo) |

Kevin Heffernan (Dublin) |

Competition structure

Gaelic sports at all levels are amateur, in the sense that the athletes, even those playing at elite level, do not receive payment for their performance.

The main competitions at all levels of Gaelic football are the League and the Championship. Of these it is the Championship (a knock-out tournament) that tends to attain the most prestige.

The basic unit of each game is organised at the club level, which is usually arranged on a parochial basis. Local clubs compete against other clubs in their county with the intention of winning the County Club Championship at senior, junior or intermediate levels (for adults) or under-21, minor or under-age levels (for children). A club may field more than one team, for example a club may field a team at senior level and a "seconds" team at junior or intermediate level. This format is laid out in the table below:

| Name | Description |

|---|---|

| Senior | Contested by the top adult teams |

| Junior | Contested by the weak adult teams, often from smaller communities |

| Intermediate | Contested by the remainder of the teams as a link between Senior and Junior |

| Name | Description |

|---|---|

| Under-21 | Contested by players under the age of 21 |

| Minor | Contested by players under the age of 18 |

| Under-age | Contested by players of all ages between under-17 and under-6 |

Clubs may come together in districts for the County Championship or compete on their own.

Though the island of Ireland was partitioned between two states by the British parliament in 1920, the organisation of Gaelic games (like that of most cultural organisations and religions) continues on an All-Ireland basis. At the national level, Ireland's Gaelic games are organised in 32 GAA counties, most of which are identical in name and extent to the 32 administrative counties on which local government throughout the island was based until the late 20th century.[22] The term "county" is also used for some overseas GAA places, such as London and New York. Clubs are also located throughout the world, in other parts of the United States, in Great Britain, in Canada, in Asia, in Australasia and in continental Europe.

The level at which county teams compete against each other is referred to as inter-county (i.e. similar to international). A county panel—a team of 15 players, plus a similar number of substitutes—is formed from the best players playing at club level in each county. The most prestigious inter-county competition in Gaelic football is the All-Ireland Championship. The highest level national championship is called the All-Ireland Senior Football Championship. Nearly all counties contest this tournament on an annual basis, with crowds of people thronging venues the length and breadth of Ireland—the most famous of these stadiums being Croke Park—to support their local county team, a team comprising players selected from the clubs in that county. These modified knock-out games start as provincial championships contested by counties against other counties in their respective province, the four Irish provinces of Ulster, Munster, Leinster and Connacht. The four victors in these then progress automatically to the All-Ireland series.

In the past, the team winning each provincial championship would play one of the others, at a stage known as the All-Ireland semi-finals, with the winning team from each game playing each other in the famed All-Ireland Final to determine the outright winner. A recent (1990s/2000s) re-organisation created a "back door" method of qualifying, with teams knocked out during the provincial rounds of the All-Ireland Championship now acquiring a second chance at glory. Now the four victorious teams at provincial level enter the recently created All-Ireland quarter-finals instead, where they compete against the four remaining teams from the All-Ireland Qualifiers to progress to the All-Ireland semi-finals and then the All-Ireland Final. This re-organisation means that one team may defeat another team in an early stage of the championship, yet be defeated and knocked out of the tournament by the same team at a later stage. It also means a team may be defeated in an early stage of the championship, yet be crowned All-Ireland champions—as Tyrone were in 2005 and 2008.

The secondary competition at inter-county level is the National League. The National Football League is held every spring and groups counties in four divisions according to their relative strength. As at local (county) levels of Gaelic football, the League at national level is less prestigious than the Championship—however, in recent years attendances have grown, as has interest from the public and from players. This is due in part to the 2002 adoption of a February–April timetable, in place of the former November start, as well as the provision of Division 2 final stages. Live matches are aired on the international channel Setanta Sports and the Irish language channel TG4, with highlights shown on RTÉ Two.

There are also All-Ireland championships for county teams at Junior, Under-21 and Minor levels, and provincial and national club championships, contested by the teams that win their respective county championships.

See also

- All-Ireland Senior Football Championship

- All-Ireland Sevens Football

- Ladies' Gaelic football

- List of footballers (Gaelic football)

- List of Gaelic football clubs

- Sport in Ireland

- Comparison of Gaelic football and Australian rules football

- Comparison of Gaelic football and rugby union

- Association football in Northern Ireland

- Association football in the Republic of Ireland

Notes

- Ireland, T.E.C. (2000). Irish-English/English-Irish Easy Reference Dictionary. Roberts Rinehart. p. 197. ISBN 9781461660316. Retrieved 7 December 2014.

- The sport is also sometimes referred to in Dublin as "Gah": see Kelly, Fiach (30 June 2008). "Plenty to give out about for the Dubs". Irish Independent. Retrieved 18 September 2009.; "The Biggest Traditional Irish Sports". Retrieved 12 April 2012.

- "Irish Gaelic Football". Accessed 19 September 2011.

- Corry, Eoghan (2005). The GAA Book of Lists. Hodder Headline Ireland. p. 238.

- Corry, Eoghan (2010). The History of Gaelic Football. Gill & MacMillan Ireland. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-7171-4818-9.

- Mahon, Jack (2001). A History of Gaelic Football. Gill &MacMillan. ISBN 0-7171-3279-X.

- Orejan, Jaime (Spring 2006). "The History of Gaelic Football and the Gaelic Athletic Association" (PDF). Sport Management and Related Topic Journal. 2 (2): 46. Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- "Football - History and Evolution".

- "Pupil Worksheets SEN" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2008.

- "Get Inspired: How to get into Gaelic football". BBC Sport. 19 July 2013. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

...By 1958, Wembley Stadium was being used to host annual exhibition games of Gaelic football in England—more than 40,000 spectators came to watch in 1962...

- "GAA pitch size". BBC Sport NI. 11 October 2005. Retrieved 18 September 2009.

- GAA Official Guide – Part 2 (PDF). Gaelic Athletic Association. 2009. p. 8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 May 2016. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

A team shall consist of fifteen players.

- "GAA Official Guide 2016, Part 2, Rule 4.4 ii (p.16)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 January 2017. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- "GAA have announced that the 'mark' will be introduced across the board on January 1". Irish Independent. 30 November 2016.

- Sweeney, Peter (13 January 2019). "The view from the ground on football's rules experiment" – via www.rte.ie. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Moran, Seán. "GAA officials and referees brace themselves as new rules kick in, and this time it's for real". The Irish Times. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- "All About Football". Archived from the original on 4 February 2009. Retrieved 18 September 2009.

- "Official Guide – Part 2" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 May 2013.GAA Rules 2012, p. 74–81, Rule 5

- "GAA pass controversial 'black card' rule". Irish Independent. 23 March 2013. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- "Official Guide – Part 2" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 May 2013. GAA Rules 2012, pp. 82–83, Rule 6

- Corry, Eoghan (2005). The GAA Book of Lists. Hodder Headline Ireland. p. 238.

- The administrative counties have been rearranged in the 20th century. Northern Ireland's original six counties are now divided into 26 local government districts, while the Republic of Ireland's 26 counties have been redrawn, leading to a modern local governmental unit total of 33. The GAA's 32 counties are mainly named for the administrative counties as they existed when the Association was formed, with some exceptions (such as Derry and Laois). While the former administrative county borders are generally respected, a GAA county may occasionally open its competitions to clubs that are wholly or partly based in neighbouring counties.

References

- Jack Mahon, 2001, A History of Gaelic Football Dublin: Gill & Macmillan. (ISBN 0-7171-3279-X)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gaelic football. |

- Gaelic football on GAA website