Bretons

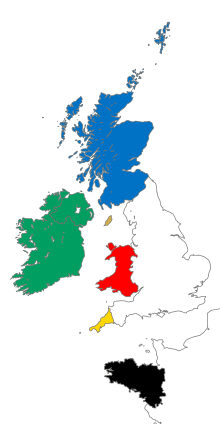

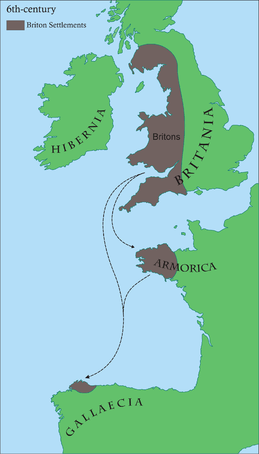

The Bretons (Breton: Bretoned, Breton pronunciation: [breˈtɔ̃nɛt]) are a Celtic[7][8] ethnic group and people native to historical region Brittany. They trace much of their heritage to groups of Brittonic speakers who emigrated from southwestern Great Britain, particularly Cornwall and Devon, mostly during the Anglo-Saxon invasion of Britain. They migrated in waves from the 3rd to 9th century (most heavily from 450 to 600) into Armorica, which was subsequently named Brittany after them.[9]

Une Jeune Bretonne ("A young Breton woman"), painting by Roderic O'Conor | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 6–8 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 6–7 million | |

| | 3,120,288[1] · [note 1] |

| Loire-Atlantique | 1,246,798[2] · [note 2] |

| | 1,500,000 [3] |

| Le Havre | 70,000[4] |

| 14,290[5] | |

| unknown | |

| Languages | |

| French, Breton, Gallo | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Roman Catholic | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Celts: Britons (Cornish, English and Welsh) Gaels (Irish, Manx, Scots),[6] | |

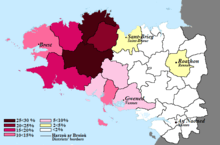

The main traditional language of Brittany is Breton (Brezhoneg), spoken in Lower Brittany (i.e. the western part of the peninsula). Breton is spoken by around 206,000 people as of 2013.[10] The other principal minority language of Brittany is Gallo; Gallo is spoken only in Upper Brittany, where Breton is less dominant. As one of the Brittonic languages, Breton is related closely to Cornish and more distantly to Welsh, while the Gallo language is one of the Romance langues d'oïl. Currently, most Bretons' native language is standard French.

Brittany and its people are counted as one of the six Celtic nations. Ethnically, along with the Cornish and Welsh, the Bretons are Celtic Britons. The actual number of ethnic Bretons in Brittany and France as a whole is difficult to assess as the government of France does not collect statistics on ethnicity. The population of Brittany, based on a January 2007 estimate, was 4,365,500.[11] It is said that, in 1914, over 1 million people spoke Breton west of the boundary between Breton and Gallo-speaking region—roughly 90% of the population of the western half of Brittany. In 1945, it was about 75%, and today, in all of Brittany, at most 20% of Bretons can speak Breton. Brittany has a population of roughly four million, including the department of Loire-Atlantique, which the Vichy government separated from historical Brittany in 1941. Seventy-five percent of the estimated 200,000 to 250,000 Breton speakers using Breton as an everyday language today are over the age of 65.

A strong historical emigration has created a Breton diaspora within the French borders and in the overseas departments and territories of France; it is mainly established in the Paris area, where more than one million people claim Breton heritage. Many Breton families have also emigrated to the Americas, predominantly to Canada (mostly Quebec and Atlantic Canada) and the United States. People from the region of Brittany were among the first European settlers to permanently settle the French West Indies, i.e. Dominica, Guadeloupe and Martinique, where remnants of their culture can still be seen to this day. The only places outside Brittany that still retain significant Breton customs are in Île-de-France (mainly Le Quartier du Montparnasse in Paris), Le Havre and in Îles des Saintes, where a group of Breton families settled in the mid-17th century.

History

Historical origins of the Bretons

Late Roman era

In the late 4th century, large numbers of British auxiliary troops in the Roman army may have been stationed in Armorica. The 9th-century Historia Brittonum states that the emperor Magnus Maximus, who withdrew Roman forces from Britain, settled his troops in the province.

Nennius and Gildas mention a second wave of Britons settling in Armorica in the following century to escape the invading Anglo-Saxons and Scoti. Modern archaeology also supports a two-wave migration.[12]

It is generally accepted that the Brittonic speakers who arrived gave the region its current name as well as the Breton language, Brezhoneg, a sister language to Welsh and Cornish.

There are numerous records of Celtic Christian missionaries migrating from Britain during the second wave of Breton colonisation, especially the legendary seven founder-saints of Brittany as well as Gildas.

As in Cornwall, many Breton towns are named after these early saints. The Irish saint Columbanus was also active in Brittany and is commemorated accordingly at Saint-Columban in Carnac.

Early Middle Ages

In the Early Middle Ages, Brittany was divided into three kingdoms—Domnonée, Cornouaille (Kernev), and Bro Waroc'h (Broërec)—which eventually were incorporated into the Duchy of Brittany. The first two kingdoms seem to derive their names from the homelands of the migrating tribes in Britain, Cornwall (Kernow) and Devon (Dumnonia). Bro Waroc'h ("land of Waroch", now Bro Gwened) derives from the name of one of the first known Breton rulers, who dominated the region of Vannes (Gwened). The rulers of Domnonée, such as Conomor, sought to expand their territory, claiming overlordship over all Bretons, though there was constant tension between local lords.

Breton participation in the Norman Invasion of England

Bretons were the most prominent of the non-Norman forces in the Norman conquest of England. A number of Breton families were of the highest rank in the new society and were tied to the Normans by marriage.[13]

Bretons in Scotland

The Scottish Clan Stewart and the royal House of Stuart have Breton origins. Alan Rufus, also known as Alan the Red, was both a cousin and knight in the retinue of William the Conqueror.

New nobility

Following his service at Hastings, he was rewarded with large estates in Yorkshire. At the time of his death, he was by far the richest noble in England. His manorial holding at Richmond ensured a Breton presence in northern England. The Earldom of Richmond later became an appanage of the Dukes of Brittany.

Modern Breton identity

.svg.png)

Many people throughout France claim Breton ethnicity, including a few French celebrities such as Marion Cotillard,[14] Suliane Brahim,[15] Malik Zidi,[16] Patrick Poivre d'Arvor, Yoann Gourcuff, Nolwenn Leroy and Yann Tiersen.[17]

After 15 years of disputes in the French courts, the European Court of Justice recognized Breton Nationality for the six children of Jean-Jacques and Mireille Manrot-Le Goarnig; they are "European Citizens of Breton Nationality".[18] In 2015, Jonathan Le Bris started a legal battle against the French administration to claim this status.

Culture

Religion

The Breton people are predominantly members of the Catholic Church, with minorities in the Reformed Church of France and non-religious people. Brittany was one of the most staunchly Catholic regions in all of France. Attendance at Sunday mass dropped during the 1970s and the 1980s, but other religious practices such as pilgrimages have experienced a revival. This includes the Tro Breizh, which takes place in the shrines of the seven founding saints of Breton Christianity. The Christian tradition is widely respected by both believers and nonbelievers, who see it as a symbol of Breton heritage and culture.

Breton religious tradition places great emphasis on the "Seven Founder Saints":

- Paul Aurelian, at Saint-Pol-de-Léon (Breton: Kastell-Paol),

- Tudwal (Sant Tudwal), at Tréguier (Breton: Landreger),

- Brioc, at Saint-Brieuc (Breton: Sant-Brieg, Gallo: Saent-Berioec),

- Malo, at Saint-Malo (Breton: Sant-Maloù, Gallo: Saent-Malô),

- Samson of Dol, at Dol-de-Bretagne (Breton: Dol, Gallo: Dóu),

- Padarn, at Vannes (Breton: Gwened),

- Corentin (Sant Kaourintin), at Quimper (Breton: Kemper).

Pardons

A pardon is the patron saint's feast day of the parish. It often begins with a procession followed by mass in honour of the saint. Pardons are often accompanied by small village fairs. The three most famous pardons are:

- Sainte-Anne d'Auray/Santez-Anna-Wened

- Tréguier/Landreger, in honour of St Yves

- Locronan/Lokorn, in honour of St Ronan, with a troménie (a procession, 12 km long) and numerous people in traditional costumes

Tro Breizh

There is an ancient pilgrimage called the Tro Breizh (tour of Brittany) which involves pilgrims walking around Brittany from the grave of one of the Seven Founder Saints to another. Nowadays pilgrims complete the circuit over the course of several years. In 2002, the Tro Breizh included a special pilgrimage to Wales, symbolically making the reverse journey of the Welshmen Paul Aurelian, Brioc, and Samson. According to Breton religious tradition, whoever does not make the pilgrimage at least once in his lifetime will be condemned to make it after his death, advancing only by the length of his coffin each seven years.[19]

Folklore and traditional belief

Some pagan customs from the old pre-Christian tradition remain the folklore of Brittany. The most powerful folk figure is the Ankou or the "Reaper of Death".

Language

The Breton language is a very important part of Breton identity. Breton itself is one of the Brittonic languages and is closely related to Cornish and more distantly to Welsh.[20] Breton is thus an Insular Celtic language and is more distantly related to the long-extinct Continental Celtic languages such as Gaulish that were formerly spoken on the European mainland, including the areas colonised by the ancestors of the Bretons.

In eastern Brittany, a regional langue d'oïl, Gallo, developed; it shares certain areal features such as points of vocabulary, idiom, and pronunciation with Breton but is a Romance language). Neither language has official status under French law; however, some still use Breton as an everyday language (particularly the older generation) and bilingual road signs are common in the west of Brittany.

From 1880 to the mid-20th century, Breton was banned from the French school system and children were punished for speaking it in a similar way to the application of the Welsh Not in Wales during the 19th and 20th centuries. The situation changed in 1951 with the Deixonne Law allowing Breton language and culture to be taught 1–3 hours a week in the public school system on the proviso that a teacher was both able and prepared to do so. In modern times, a number of schools and colleges have emerged with the aim of providing Breton-medium education or bilingual Breton/French education.[21]

There are four main Breton dialects: Gwenedeg (Vannes), Kerneveg (Cornouaille), Leoneg (Leon) and Tregerieg (Trégor), which have varying degrees of mutual intelligibility. In 1908, a standard orthography was devised. The fourth dialect, Gwenedeg, was not included in this reform, but was included in the later orthographic reform of 1941.[21]

Breton-language media

Newspapers, magazines and online journals available in Breton include Al Lanv,[22] based in Quimper, Al Liamm,[23] Louarnig-Rouzig, and Bremañ.

There are a number of radio stations with broadcasts in the Breton language, namely Arvorig FM, France Bleu Armorique, France Bleu Breizh-Izel, Radio Bro Gwened, Radio Kerne, and Radio Kreiz Breizh.

Television programmes in Breton are also available on France 3 Breizh, France 3 Iroise, TV Breizh and TV Rennes. There are also a number of Breton language weekly and monthly magazines.[21]

Music

Fest-noz

A fest-noz is a traditional festival (essentially a dance) in Brittany. Many festoù-noz are held outside Brittany, taking regional Breton culture outside Brittany. Although the traditional dances of the fest-noz are old, some dating back to the Middle Ages, the fest-noz tradition is itself more recent, dating back to the 1950s. Fest-Noz was officially registered on Wednesday, December 5, 2012 by UNESCO on the "Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity."

Traditional dance

There are many traditional Breton dances, the most well-known being gavottes, an dro, the hanter dro, and the plinn. During the fest-noz, most dances are practised in a chain or in a circle (holding a finger); however, there are also dances in pairs and choreographed dances with sequences and figures.

Traditional Breton music

Two main types of Breton music are a choral a cappella tradition called kan ha diskan, and music involving instruments, including purely instrumental music. Traditional instruments include the bombard (similar to an oboe) and two types of bagpipes (veuze and binioù kozh). Other instruments often found are the diatonic accordion, the clarinet, and occasionally violin as well as the hurdy-gurdy. After World War II, the Great Highland bagpipe (and binioù bras) became commonplace in Brittany through the bagadoù (Breton pipe bands) and thus often replaced the binioù-kozh. The basic clarinet (treujenn-gaol) had all but disappeared but has regained popularity over the past few years.

Modern Breton music

Nowadays groups with many different styles of music may be found, ranging from rock to jazz such as Red Cardell, ethno-rock, Diwall and Skeduz as well as punk. Some modern fest-noz groups also use electronic keyboards and synthesisers, for example Strobinell, Sonerien Du, Les Baragouineurs, and Plantec.

Breton cuisine

Breton cuisine contains many elements from the wider French culinary tradition. Local specialities include:

- Crêpe – froment (sweet)

- Galette – buckwheat (savory)

- Chouchenn – a type of Breton mead

- Fars forn (far breton) – a kind of sweet suet pudding with prunes

- Kouign-amann – butter pastry

- Krampouezh (crêpes or galettes) – thin pancakes made either from wheat or buckwheat flour; usually eaten as a main course

- Lambig – apple eau de vie

- Sistr – cider

- Caramel au beurre salé - salted butter caramel

Symbols of Brittany

Traditional Breton symbols and symbols of Brittany include the national anthem Bro Gozh ma Zadoù based on the Welsh Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau. The traditional motto of the former Dukes of Brittany is Kentoc'h mervel eget bezañ saotret in Breton, or Potius mori quam fœdari in Latin. The "national day" is observed on 1 August,[24] the Feast of Saint Erwann (Saint Yves). The ermine is an important symbol of Brittany reflected in the ancient blazons of the Duchy of Brittany and also in the chivalric order, L’Ordre de l’Hermine (The Order of the Ermine).

See also

Images of Brittany

_-_Breton_Brother_and_Sister_(1871).jpg) William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Breton Brother and Sister

William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Breton Brother and Sister Paul Gauguin, Breton Girl

Paul Gauguin, Breton Girl Émile Bernard, Breton Women at a Wall

Émile Bernard, Breton Women at a Wall

.jpg) City hall of Rennes

City hall of Rennes

City of Quimper

City of Quimper City of Saint-Malo

City of Saint-Malo- The bagad of Lann-Bihoué of the French Navy

Breton pipe player

Breton pipe player

Notes

- Legal population of the administrative region of Brittany in 2007

- Legal population of Loire-Atlantique in 2007

References

- "Populations légales 2013 - Insee". Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- "Insee − Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques - Insee". Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- Rolland, Michel. "La Bretagne à Paris". Archived from the original on 2016-11-30. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- "Ils sont 70 000 ! Notre dossier sur les Bretons du Havre". Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- 2011 National Household Survey; includes 4,770 people of single and 9,525 of mixed Breton origin.

- Ed. Wade Davis and K. David Harrison (2007). Book of Peoples of the World. National Geographic Society. p. 225. ISBN 978-1-4262-0238-4.

- Minahan, James (2000). One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 179. ISBN 0313309841.

The Cornish are related to the other Celtic peoples of Europe, the Bretons,* Irish,* Scots,* Manx,* Welsh,* and the Galicians* of northwestern Spain

- Minahan, James (2000). One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 766. ISBN 0313309841.

Celts, 257, 278, 523, 533, 555, 643; Bretons, 129-33; Cornish, 178-81; Gali- cians, 277-80; Irish, 330-37; Manx, 452-55; Scots, 607-12; Welsh

- Koch, John (2005). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABL-CIO. p. 275. ISBN 978-1-85109-440-0. Retrieved September 29, 2012.

- "Breton". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2017-06-09.

- "Breton Language". Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- Léon Fleuriot, Les origines de la Bretagne: l’émigration, Paris, Payot, 1980.

- Keats-Rohan 1991, The Bretons and Normans of England 1066-1154 Archived 2011-07-24 at the Wayback Machine

- "Marion Cotillard: 'Before my family, everything was dedicated to the character'". The Guardian. August 2, 2014.

- "Suliane Brahim, le Grand Jeu". Libération. February 28, 2018.

- ifrance.com Archived August 27, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- "Yann Tiersen: ∞ (Infinity) & the Origin of Its Language". Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- "Goarnig Kozh a livré son dernier combat". Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- Bretagne: poems (in French), by Amand Guérin, published by P. Masgana, 1842: page 238.

- "Breton language". Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- "Breton language, alphabet and pronunciation". Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- Allanv.microopen.org Archived May 9, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- "Al Liamm - Degemer". Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- Pierre Le Baud, Cronicques & Ystoires des Bretons.

Bibliography

- Léon Fleuriot, Les origines de la Bretagne, Bibliothèque historique Payot, 1980, Paris, (ISBN 2-228-12711-6)

- Christian Y. M. Kerboul, Les royaumes brittoniques au Très Haut Moyen Âge, Éditions du Pontig/Coop Breizh, Sautron – Spézet, 1997, (ISBN 2-84346-030-1)

- Morvan Lebesque, Comment peut-on être Breton ? Essai sur la démocratie française, Éditions du Seuil, coll. « Points », Paris, 1983, (ISBN 2-02-006697-1)

- Myles Dillon, Nora Kershaw Chadwick, Christian-J. Guyonvarc'h and Françoise Le Roux, Les Royaumes celtiques, Éditions Armeline, Crozon, 2001, (ISBN 2-910878-13-9).

External links

Breizh.net – a non-profit association dedicated to the promotion of Brittany and the Breton language on the Internet Breizh.net