General Post Office

The General Post Office (GPO)[1] was the state postal system and telecommunications carrier of the United Kingdom until 1969. Before the Acts of Union 1707, it was the postal system of the Kingdom of England, established by Charles II in 1660.[2] Similar General Post Offices were established across the British Empire. In 1969 the GPO was abolished and the assets transferred to The Post Office, changing it from a Department of State to a statutory corporation. In 1980, the telecommunications and postal sides were split prior to British Telecommunications' conversion into a totally separate publicly owned corporation the following year as a result of the British Telecommunications Act 1981. For the more recent history of the postal system in the United Kingdom, see the articles Royal Mail and Post Office Ltd.

.svg.png) Royal Arms as used by Her Majesty's Government | |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 1660 |

| Dissolved | 1 October 1969 |

| Superseding agency | |

| Jurisdiction |

|

| Headquarters | General Post Office, St Martin's le Grand, London EC2 |

| Agency executives |

|

| Parent agency | Her Majesty's Government |

Originally, the GPO was a state monopoly covering the despatch of items from a specific sender to a specific receiver, which was to be of great importance when new forms of communication were invented. The creation of the GPO, then the General Letter Office, was legislated for by the Parliament of England after The Restoration, which returned the British Isles to monarchy under the House of Stuart. The postal service was known as the Royal Mail because it was built on the distribution system for royal and government documents. An earlier system had been set up under the republican Commonwealth of England, Scotland, and Ireland in 1657 under a Postmaster General, whose office was created anew in 1661 and existed until its abolition, along with the GPO itself, by the Post Office Act 1969.

Early postal services

In 1657 an Act entitled Postage of England, Scotland and Ireland Settled set up a system for the British Isles, which had been unified under Oliver Cromwell as a result of the Wars of the Three Kingdomsand enacted the position of Postmaster General. The Act also reasserted the postal monopoly for letter delivery and for post horses. After the Restoration in 1660, a further Act (12 Car II, c.35) confirmed this and the post of Postmaster-General, the previous Cromwellian Act being void.[3]

1660 saw the establishment of the General Letter Office in the restored Kingdom of England, which would later become the General Post Office (GPO).[4] A similar position evolved in the Kingdom of Scotland prior to the 1707 Acts of Union.

The GPO created a network of post offices where senders could submit items. All post was transferred from the post office of origination to distribution points called sorting stations, and from there the post was then sent on for delivery to the receiver of the post. Initially it was the recipient of the post who paid the fee, and he had the right to refuse to accept the item if he did not wish to pay. The charge was based on the distance the item had been carried so the GPO had to keep a separate account for each item. In 1840 the Uniform Penny Post was introduced, which incorporated the two key innovations of a uniform postal rate, which cut administrative costs and encouraged use of the system, and adhesive pre-paid stamp.

Headquarters

.jpg)

The first general post office in London opened in 1643,[5] just 8 years after King Charles I legalised use of the royal posts for private correspondence.[6] It was probably on Cloak Lane near Dowgate Hill.[5] Coffee houses in the City such as Lloyd's and Garraway's organised private transport of mail among their patrons. The Royal Mail (which, following its legalisation, held a nominal monopoly on such delivery services) moved its headquarters to Lombard Street in the City in 1678 to better curtail such practices.[5]

After purchasing adjacent property in the centre of London's financial district gradually became prohibitively expensive, the General Post Office purchased slums on the east side of St. Martin's Le Grand and cleared them to establish a new headquarters, Britain's first purpose-built mail facility. The General Post Office, designed with Grecian ionic porticoes by Sir Robert Smirke, was built between 1825 and 1829, ran 400 feet (120 m) long and 80 feet (24 m) deep, and was lit with a thousand gas burners at night.[5]

In the mid-19th century there were four branch offices in London: one in the City at Lombard Street; two in the West End at Charing Cross and Old Cavendish Street near Oxford Street; and one south of the Thames in Borough High Street.[7]

In the 1870s, a new building was added on the western side of the street to house the telegraph department, and the General Post Office North was built immediately north of the telegraph building in the 1890s. When the Central London Railway was built in 1900 its nearby station was named "Post Office". Smirke's building was felt to be too small by this time, however, and in 1910 the headquarters was moved to the King Edward Building. In 1912, the former GPO East was demolished: the current headquarters of BT, a post World War II building, occupies the site of the old Telegraph Office.

New communication systems

When new forms of communication came into existence in the 19th and early 20th centuries the GPO claimed monopoly rights on the basis that like the postal service they involved delivery from a sender and to a receiver. The theory was used to expand state control of the mail service into every form of electronic communication possible on the basis that every sender used some form of distribution service. These distribution services were considered in law as forms of electronic post offices. This applied to telegraph and telephone switching stations.

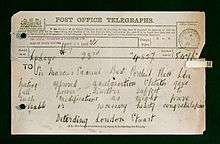

Telegraph

In the mid 19th century several private telegraph companies were established in the UK. The Telegraph Act 1868 granted the Postmaster-General the right to acquire inland telegraph companies in the United Kingdom and the Telegraph Act 1869 conferred on the Postmaster-General a monopoly in telegraphic communication in the UK. The responsibility for the 'electric telegraphs' was officially transferred to the GPO in 1870. Overseas telegraphs did not fall within the monopoly. The private telegraph companies that already existed were bought out. The new combined telegraph service had 1,058 telegraph offices in towns and cities and 1,874 offices at railway stations. 6,830,812 telegrams were transmitted in 1869 producing revenue of £550,000.[8]

London's Central Office in the first decade of nationalized telegraphy created two levels of service. High-status circuits catering to the state, international trade, sporting life, and imperial business. Low-status circuits directed toward the local and the provincial. These distinct telegraphic orbits were connected to different types of telegraph instruments operated by differently gendered telegraphists.[9]

Telephone

The Post Office commenced its telephone business in 1878, however the vast majority of telephones were initially connected to independently run networks. In December 1880, the Post Master General obtained a court judgement that telephone conversations were, technically, within the remit of the Telegraph Act. The General Post Office then licensed all existing telephone networks.

The effective nationalisation of the UK telecommunications industry occurred in 1912 with the takeover of the National Telephone Company which left only a few municipal undertakings independent of the GPO (in particular Hull Telephones Department and the telephone system of Guernsey).

The telephone systems of Jersey and the Isle of Man, obtained from the NTC were offered for sale to the respective governments of the islands. Both initially refused, but the States of Jersey did eventually take control of their island's telephones in 1923.

Radio

The development of radio links for sending telegraphs led to the Wireless Telegraphy Act 1904, which granted control of radio waves to the General Post Office, who licensed all senders and receivers. This placed the Post Office in a position of control over radio and television broadcasting as those technologies were developed.

Control of broadcasting

In 1922 a group of radio manufacturers formed the British Broadcasting Company (BBC), which was the sole organisation granted a broadcasting licence by the GPO. In 1927, the original BBC was dissolved and reformed by Royal Charter as the British Broadcasting Corporation.

From the start the GPO had trouble with competitive pirate radio broadcasters who found ways to deliver electronic messages to British receivers without first obtaining a GPO licence. These competitors were well aware of the fact that the GPO would never grant them such a licence. To police these unlicensed stations the GPO evolved its own force of detectives and "detector vans".

The radio regulation functions were transferred to the Independent Broadcasting Authority and later Ofcom. Due to its regulatory role, as well as its expertise in developing long-distance communication networks, the GPO was contracted by the BBC, and the ITA in the 1950s and 60s, to develop and extend their television networks. A network of transmitters was built, connected at first by cable, and later by microwave radio links. The Post Office also took responsibility for the issuing of television licence fees (and radio, until 1971), and the prosecution of evaders until 1991.

Growth in telecommunications

After the Second World War, there began to be an unprecedented demand for telephone services. In addition, there was the need to make comprehensive repairs, and upgrades to a network which had been severely degraded by war, and lack of investment. Waiting lists for new telephone lines quickly emerged, and persisted for several decades. To alleviate the situation, the Post Office began to provide shared service lines, each known as a party line. Most of the line was shared between two subscribers usually splitting off to each within sight of the houses, and both lines attracted a small discount; however, this arrangement had its disadvantages.

At this time, the majority of lines in rural, and regional areas (particularly in Scotland and Wales) were still manually switched. This inhibited growth, and caused bottlenecks in the network, as well as being labour and cost-intensive. The Post Office began to introduce automatic switching, and replaced all of its 6,000 exchanges. Subscriber Trunk Dialling (STD) was also added from 1958, which allowed subscribers to dial their own long-distance calls.

Banking services

The Post Office Savings Bank was introduced in 1861, when there were few banks outside major towns. By 1863, 2,500 post offices were offering a savings service. Gradually more financial services were offered by post offices, including government stocks and bonds in 1880, insurance and annuities in 1888, and war savings certificates in 1916. In 1909 old age pensions were introduced, payable at post offices.[10] In 1956 a lottery bond called the Premium Bond was introduced.

In the mid-1960s the GPO was asked by the government to expand into banking services which resulted in the creation of the National Giro.[10]

In 1969, the Post Office Savings Bank was transferred to the Treasury, and renamed National Savings.[11]

Reorganisation

Ireland

In 1831 the office of Postmaster General of Ireland was amalgamated with the equivalent office for Great Britain. The GPO thereafter operated throughout Great Britain and Ireland for the next 90 years. Following the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921 responsibility for posts and telegraphs transferred to the new Provisional Government and then, upon the formal independence of the Irish Free State in December 1922, to the Free State Government. A Postmaster General was initially appointed by the Free State Government, being replaced by the office of Minister for Posts and Telegraphs in 1924. An early visible manifestation was the repainting of all post boxes green instead of red. In 1984 the Department of Posts and Telegraphs was replaced by the separate Irish state-owned companies An Post and Telecom Éireann.

1930s reviews

The Bridgeman Committee, chaired by Lord Bridgeman, was set up in 1932 to investigate criticisms of the General Post Office and reported the same year.[12] It highlighted defects in the structure of the organisation. The Gardiner Committee, chaired by Sir Thomas Gardiner, was set up to investigate improvements in efficiency and reported in 1936. The report recommended the setting up of eight provincial regions outside London,[notes 1] and the introduction of the London Postal Region and London Telecommunications Region for the capital and surrounding area. The changes were implemented between 1936 and 1940.

Dissolution

Under the Post Office Act 1969, the assets of the Post Office were transferred from a government department with a Royal Charter to a statutory corporation. Responsibility for telecommunications was given to Post Office Telecommunications, the successor of the GPO Telegraph and Telephones department, with its own separate budget and management. A rebranding exercise also took place, with the word 'General' being dropped from the name. In 1975, the familiar striped 'Post Office' lettering was introduced, which continues to be in use by Royal Mail.

Jersey Post and Guernsey Post became independent in 1969. Isle of Man Post purchased GPO assets on the island and commenced operation on 5 July 1973.

The British Telecommunications Act 1981 split off the telecommunications business to form the British Telecommunications corporation, leaving the Post Office corporation with the Royal Mail, parcels, Post Office Counters and National Giro businesses. British Telecommunications was converted to British Telecommunications plc in 1984, and was privatised. Girobank was divested to Alliance & Leicester in 1990.

As part of the Postal Services Act 2000, the businesses of the Post Office were transferred in 2001 to a public limited company, Consignia plc, which was quickly renamed Royal Mail Holdings plc. The government became the sole shareholder in Royal Mail Holdings plc and its subsidiary Post Office Ltd.

Finally, on 5 April 2007, the government published the Dissolution of the Post Office Order 2007, under which the old Post Office statutory corporation was formally abolished with effect from 1 May 2007.

Links to the intelligence services

For some time a department called the GPO Special Investigations Unit was responsible for intercepting letters ("postal interception") as part of British intelligence service operations. The unit had branches in every major sorting office in the UK and in St Martin's Le Grand GPO, near St Paul's Cathedral. Letters targeted for interception by the Special Investigations Unit were steamed open and the contents photographed, and the photographs were then sent in unmarked green vans to MI5.[13]

Military links

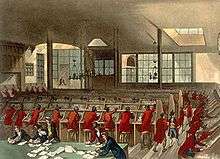

.jpg)

_p095_POST_OFFICE.jpg)

In 1868, as part of the Volunteer Movement, John Lowther du Plat Taylor, Private Secretary to the Postmaster General, raised the 49th Middlesex Rifle Volunteers Corps (Post Office Rifles) from GPO employees, who had been either members of the 21st Middlesex Rifles Volunteer Corps (Civil Service Rifles) or special constables enrolled to combat against Fenian attacks on London in 1867/68.

The regiment was restyled 24th Middlesex Rifle Volunteers Corps (Post Office Rifles) in 1880 as part of the Cardwell Reforms.

‘M' Company, 24th Middlesex Rifle Volunteers Corps, was formed by Royal Warrant in 1882 as the Army Post Office Corps (APOC). This newly formed Army Reservist company saw active service providing a postal service to the British military expeditions to Egypt (1882), Suakin (1885) and the Anglo Boer War (1899–1902). The APOC was eventually subsumed by the Royal Engineers in 1913 to re-emerge as the Royal Engineers (Postal Section) Special Reserve. The Postal Section provided the Army Postal Service (now British Forces Post Office) in the First and Second World Wars and in 1993 became the Postal & Courier Service Royal Logistic Corps.

In 1883 the regiment raised 'L’ Company as a Telegraph Corps, a year later it was redesignated as the Telegraph Reserve Royal Engineers. Its role was to supplement the Regular Army's telegraph services operated by the Royal Engineers.

After the Haldane Reforms the regiment kept its association with the Post Office and continued to recruit postal workers into the Territorial Force under its new title '8th (City of London) Battalion, The London Regiment (Post Office Rifles)' in 1908. It served as an infantry regiment in the First World War (1914–18). Sergeant Alfred Joseph Knight was awarded the Victoria Cross for his bravery in the Capture of Wurst Farm (20 September 1917). The regiment was disbanded in 1921.

During World War II the generation of engineers trained by the GPO for its telecommunications operations were to have important roles in the British development of radar and in code breaking. The Colossus computers used by Bletchley Park were built by GPO engineer Tommy Flowers and his team at the Post Office Research Station in Dollis Hill.

In 1916, during World War I, the General Post Office, Dublin was a focus of the Easter Rising, during which the GPO served as the headquarters of the uprising's leaders. It was from outside this building on the 24th of April 1916, that Patrick Pearse read out the Proclamation of the Irish Republic.[14] The building was destroyed by fire in the course of the rebellion, save for the granite facade, and not rebuilt until 1929, by the Irish Free State government.

See also

Notes

- Home Counties; Midland; Northern Ireland; North-Eastern; North-Western; Wales and Border Counties; Scotland; South-Western

References

- "Summary of Post Office history". The British Postal Museum & Archive. Archived from the original on 17 May 2011.

- Marshall, Allan (2003). Intelligence and Espionage in the Reign of Charles II, 1660–1685. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 79.

- "Charles II, 1660: An Act for Erecting and Establishing a Post Office. | British History Online". www.british-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- "Division No. 1 (Postal Services Bill) [15 Jun 2000] – Column 1782". Volume No. 613 – Part No. 104. 15 June 2000. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- "The General Post Office East: 1829–1912". Postal Heritage. Retrieved 2 October 2013.

- "The Secret Room". The British Postal Museum & Archive. 2011. Archived from the original on 31 August 2012. Retrieved 2 October 2013.

- "Victorian London – Communications – Post – General Post Office". The Dictionary of Victorian London. Lee Jackson.

- Tom Standage, The Victorian Internet: The remarkable story of the telegraph and the nineteenth century's online pioneers (Phoenix, 1998) online.

- Katie Hindmarch-Watson, "Embodying Telegraphy in Late Victorian London." Information & Culture 55#1 (2020): 10-29 online

- Business and Enterprise Committee (23 June 2009). "Post Offices – Securing their Future: Annex A – The development of the post office network". UK Parliament. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

- Story of NS&I Archived 10 October 2013 at WebCite National Savings & Investments, 2013. Retrieved 10 October 2013. Archived here.

- "Events in Telecommunications History: 1932". BT Archives. British Telecom. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- Saunders, Frances Stonor (9 April 2015). "Stuck on the Flypaper". London Review of Books. 37 (7): 3. Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- "Easter Rising – Day 1: Rebels on the streets". The Irish Times. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

Further reading

- Bruton, Elizabeth. "Something in the air: The Post Office and early wireless, 1882–1899." in Knowledge Management and Intellectual Property (Edward Elgar, 2013).

- Campbell-Smith, Duncan. Masters of the Post: The Authorized History of the Royal Mail (Penguin 2012)

- Clinton, Allan. Post Office Workers: A Trade Union and Social History (George Allen and Unwin, 1984)

- Daunton, M. J. Royal Mail: The Post Office Since 1840 (Athlone, 1985).

- Hemmeon, Joseph Clarence. The history of the British post office (Harvard University Press, 1912) online.

- Hochfelder, David. "A comparison of the postal telegraph movement in Great Britain and the United States, 1866–1900." Enterprise & Society 1.4 (2000): 739-761.

- Lin, Chih-lung. "The British dynamic mail contract on the North Atlantic: 1860–1900." Business History 54.5 (2012): 783-797.

- Morus, Iwan Rhys “‘The Nervous System Of Britain’: Space, Time, and the Electric Telegraph in the Victorian Age,” British Journal for the History of Science 33#4 (2000): 455–75, online

- Perry, C. R. The Victorian Post Office: The Growth of a Bureaucracy (Boydell Press, 1992)

- Standage, Tom. The Victorian Internet: The remarkable story of the telegraph and the nineteenth century's online pioneers (Phoenix, 1998) online

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to General Post Office (United Kingdom). |

- The British Postal Museum & Archive

- An 18th-Century listing of expenses, shipping schedules, and regulations for the office on Lombard Street

- BT Archives

- Connected Earth (History of Communications)

- Bath Postal Museum

- Royal Mail Group – About us

- Site for former Leicestershire Telegram Messenger Boys

- G.P.O. GLASGOW (c.1961) (archive film showing functions of the telephone exchange, enquiries and repair – from the National Library of Scotland: SCOTTISH SCREEN ARCHIVE)