Gough Island

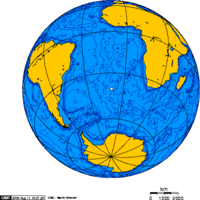

Gough Island (/ɡɒf/), also known historically as Gonçalo Álvares after the Portuguese explorer, is a rugged volcanic island in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is a dependency of Tristan da Cunha and part of the British overseas territory of Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha. It is about 400 km (250 mi) south-east of the Tristan da Cunha archipelago (which includes Nightingale Island and Inaccessible Island), 2,400 km (1,500 mi) north-east from South Georgia Island, 2,700 km (1,700 mi) west from Cape Town, and over 3,200 km (2,000 mi) from the nearest point of South America.

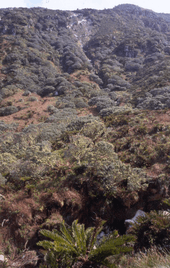

View of Gough Island | |

Gough Island Gonçalo Álvares | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | South Atlantic Ocean |

| Coordinates | 40°19′0″S 9°56′0″W |

| Archipelago | Tristan da Cunha |

| Area | 91 km2 (35 sq mi) |

| Length | 13 km (8.1 mi) |

| Width | 7 km (4.3 mi) |

| Highest elevation | 910 m (2,990 ft) |

| Highest point | Edinburgh Peak |

| Administration | |

United Kingdom | |

| St Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha | |

| Criteria | Natural: (vii), (x) |

| Reference | 740 |

| Inscription | 1995 (19th session) |

| Designated | 20 November 2008 |

| Reference no. | 1868[1] |

_Botany_(1981)_(20450043601).jpg)

Gough Island is uninhabited except for the personnel of a weather station (usually six people) which the South African National Antarctic Programme has maintained, with British permission, continually on the island since 1956. It is one of the most remote places with a constant human presence. It is part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site of Gough and Inaccessible Islands.

Name

The island was first named Ilha de Gonçalo Álvares on Portuguese maps. It was named Gough Island after the British mariner Captain Charles Gough of the Richmond, who sighted the island in 1732. Confusion of the unusual Portuguese saint name Gonçalo with Spanish Diego led to the misnomer Diego Alvarez Island in English-language sources from the 1800s to 1930s.[2][3][4] However, the most likely explanation is that it was simply a misreading of 'Is de Go Alvarez', the name by which the island is represented on some of the early charts, the 'de Go' mutating into 'Diego'.[5]

History

The details of the discovery of Gough Island are unclear, but the most likely occasion is July 1505 by the Portuguese explorer Gonçalo Álvares.[6] Maps during the next three centuries named the island after him. On some later maps, this was erroneously given as Diego Alvarez.

According to some historians, the British merchant Anthony de la Roché was the first to land on the island, in the austral autumn of 1675.[7][8][9]

Charles Gough rediscovered the island on 3 March 1732, thinking it was a new find.[10] It had been named Gonçalo Álvares since 1505 after the captain of Vasco da Gama's flagship on his epic voyage to the east, and under this name it was marked with reasonable accuracy on the charts of the South Atlantic during the following 230 or so years. Then, in 1732, Captain Gough of the British ship Richmond reported the discovery of a new island, which he placed 400 miles to the east of Gonçalo Álvares. Fifty years later cartographers realised that the two islands were the same, and despite the priority of the Portuguese discovery, and the greater accuracy of the position given by them, "Gough's Island" was the name adopted.[11]

In the early 19th century, sealers sometimes briefly inhabited the island. The earliest known example is a sealing gang from the U.S. ship Rambler (Captain Joseph Bowditch) which remained on the island in the 1804–1805 season.[12] The sealing era lasted from 1804 to 1910 during which 34 sealing vessels are known to have visited the island, one of which was lost offshore.[13]

The Scottish National Antarctic Expedition on the Scotia made the first visit to the island by a scientific party on 21 April 1904, when William Speirs Bruce and others collected specimens.[14] The Shackleton–Rowett Expedition also stopped at the island in 1922.[15]

Gough Island was formally claimed in 1938 for Britain, during a visit by HMS Milford of the Royal Navy.[16] In 1995, the island was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. In 2004, the site was extended to include Inaccessible Island and renamed Gough and Inaccessible Islands.

Gough Island is the only place outside South America from which the solar eclipse of September 12, 2034, will be visible; the centre of the path of totality crosses over the island.

Geography and geology

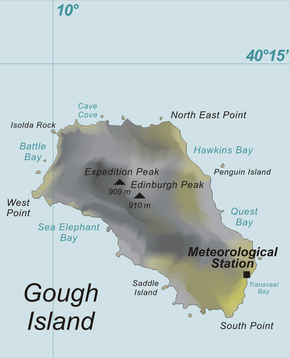

Gough Island is roughly rectangular with a length of 13 km (8.1 mi) and a width of 7 kilometres (4.3 mi). It has an area of 91 km2 (35 sq mi) and rises to heights of over 900 m (3,000 ft) above sea level.[17] Topographic features include the highest peak, Edinburgh Peak, Hags Tooth, Mount Rowett, Sea Elephant Bay, Quest Bay, and Hawkins Bay.

It includes small satellite islands and rocks such as Southwest Island, Saddle Island (South), Tristiana Rock, Isolda Rock (West), Round Island, Cone Island, Lot's Wife, Church Rock (North), Penguin Island (Northeast), and The Admirals (East).

Climate

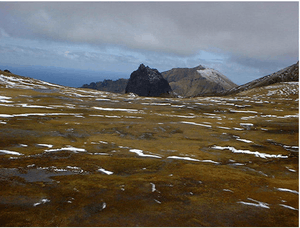

According to the Köppen system, Gough Island features an oceanic climate (Cfb). Gough Island's temperatures are between 11 °C (52 °F) and 17 °C (63 °F) during the day year-round, due to its isolated position far out in the Atlantic Ocean. The Atlantic is much cooler in the southern hemisphere than the northern, but frosts are still very rare. As a result, summers are not very hot. It features a similar climate to the Fiordland area of New Zealand, the west coast of Scotland, or the Alaskan Panhandle. Precipitation is high during the entire year, and sunshine hours are few. Snow falls in the interior, but is rare at sea level[18].

| Climate data for Gough Island (1961–1990, extremes 1956–1990) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 26.4 (79.5) |

25.7 (78.3) |

25.9 (78.6) |

22.6 (72.7) |

20.5 (68.9) |

20.6 (69.1) |

19.3 (66.7) |

21.7 (71.1) |

19.3 (66.7) |

21.4 (70.5) |

23.9 (75.0) |

25.1 (77.2) |

26.4 (79.5) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 17.2 (63.0) |

17.4 (63.3) |

16.9 (62.4) |

15.4 (59.7) |

13.7 (56.7) |

12.4 (54.3) |

11.5 (52.7) |

11.2 (52.2) |

11.5 (52.7) |

12.9 (55.2) |

14.9 (58.8) |

16.2 (61.2) |

14.3 (57.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 13.9 (57.0) |

14.4 (57.9) |

13.9 (57.0) |

12.8 (55.0) |

11.3 (52.3) |

10.0 (50.0) |

9.1 (48.4) |

8.9 (48.0) |

8.9 (48.0) |

10.1 (50.2) |

11.9 (53.4) |

13.2 (55.8) |

11.5 (52.7) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 11.1 (52.0) |

11.6 (52.9) |

11.3 (52.3) |

10.4 (50.7) |

8.9 (48.0) |

7.6 (45.7) |

6.6 (43.9) |

6.5 (43.7) |

6.6 (43.9) |

7.8 (46.0) |

9.4 (48.9) |

10.3 (50.5) |

9.0 (48.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 5.3 (41.5) |

5.1 (41.2) |

4.8 (40.6) |

3.7 (38.7) |

1.4 (34.5) |

0.1 (32.2) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

−2.7 (27.1) |

0.2 (32.4) |

0.5 (32.9) |

2.4 (36.3) |

4.1 (39.4) |

−2.7 (27.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 210 (8.3) |

183 (7.2) |

254 (10.0) |

276 (10.9) |

286 (11.3) |

310 (12.2) |

273 (10.7) |

304 (12.0) |

270 (10.6) |

249 (9.8) |

213 (8.4) |

241 (9.5) |

3,069 (120.9) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 16 | 13 | 18 | 19 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 21 | 20 | 18 | 16 | 18 | 225 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 81 | 82 | 82 | 82 | 82 | 83 | 83 | 83 | 81 | 81 | 81 | 81 | 82 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 183.8 | 148.8 | 123.3 | 95.6 | 83.7 | 60.4 | 71.7 | 87.5 | 101.6 | 128.5 | 161.4 | 182.9 | 1,429.2 |

| Source 1: NOAA,[19] Deutscher Wetterdienst (extremes)[20] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: climate-charts.com[21] | |||||||||||||

Fauna and flora

Gough and Inaccessible Island are a protected wildlife reserve, which has been designated a World Heritage Site by UNESCO.[22] It has been described as one of the least disrupted ecosystems of its kind and one of the best shelters for nesting seabirds in the Atlantic. In particular, it is host to almost the entire world population of the Tristan albatross (Diomedea dabbenena) and the Atlantic petrel (Pterodroma incerta).[23] The island is also home to the almost flightless Gough moorhen,[24] and the critically endangered Gough bunting.

Birds

The island has been identified as an Important Bird Area (IBA) by BirdLife International for its endemic landbirds and as a breeding site for seabirds. Birds for which the IBA has conservation significance include northern rockhopper penguins (30,000 breeding pairs), Tristan albatrosses (1500–2000 pairs), sooty albatrosses (5000 pairs), Atlantic yellow-nosed albatrosses (5000 pairs), broad-billed prions (1,750,000 pairs), Kerguelen petrels (20,000 pairs), soft-plumaged petrels (400,000 pairs), Atlantic petrels (900,000 pairs), great-winged petrels (5000 pairs), grey petrels (10,000 pairs), great shearwaters (100,000 pairs), little shearwaters (10,000 pairs), grey-backed storm petrels (10,000 pairs), white-faced storm petrels (10,000 pairs), white-bellied storm petrels (10,000 pairs), Antarctic terns (500 pairs), southern skuas (500 pairs), Gough moorhens (2500 pairs) and Gough buntings (3000 individuals).[25]

Mammals

The island has a large breeding population of subantarctic fur seals and some southern right whales still migrate around the island.

House mice are currently present on the island. (see Invasive Species)

Invasive species

Pearlwort (Sagina procumbens)

In 1998 a number of procumbent pearlwort (Sagina procumbens) plants were found on the island which are capable of dramatically transforming the upland plant ecosystem (as it has on the Prince Edward Islands). [26] Eradication efforts are ongoing but are expected to require years of 'concerted effort'. [27]

House mice

In April 2007 researchers published evidence that predation by introduced house mice on seabird chicks is occurring at levels that might drive the Tristan albatross and the Atlantic petrel to extinction.[28] As of October 2018, it is estimated that as many as 2,000,000 fewer eggs and chicks are being raised due to the impact of mice on the island, threatening the extinction of several species of seabirds that breed exclusively or nearly exclusively on Gough Island.[29] The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds awarded £62,000 by the UK government's Overseas Territories Environment Programme to fund additional research on the Gough Island mice and a feasibility study of how best to deal with them. The grant also paid for the assessment of a rat problem on Tristan da Cunha island. Trials for a method of eradicating the mice through baiting were commenced,[30] and ultimately a £9.2m eradication programme was planned, and set to begin in 2020, with the island expected to be mouse free by 2022. The inception of this programme in 2020 was confirmed in 2018. The programme will use helicopters to drop cereal pellets containing the rodenticide brodifacoum. Gough has also been identified as the third most important island in the world (out of 107 islands) to be targeted for the removal of non-native invasive mammals to save threatened species from extinction and make major progress towards achieving global conservation targets.[31]

The proposed cull has been criticised by some animal rights groups, with the director of Animal Aid stating "We don’t feel we have the right to choose some animals over others ... We don’t agree with any culling for so-called conservation purposes. The conservation priority should be making sure wild spaces are protected, but allowing nature to do its thing. The species that we prefer to succeed may not, but we should let that happen rather than deciding to micromanage, control and inflict suffering on the species we don’t like."[32]

Weather station

A weather station has been operating on Gough Island since 1956. It is operated as part of the network of the South African Weather Service. Because cold fronts approach South Africa from the south-west, the Gough station is particularly important in forecasting winter weather. Initially it was housed in the station at The Glen, but moved in 1963 to the South lowlands of the island, more precisely 40°20′57.68″S 9°52′49.13″W. The new location improved the validity and reliability of the data acquired for use in modeling.

Human presence

Each year a new overwintering team arrives by ship from Cape Town (beginning in 2012, the S. A. Agulhas II) to staff the weather station and perform scientific research. The team for a particular year may be termed as "Gough" and an expedition number: for example, the 1956 team were "Gough 01", and the team for 2013 were "Gough 58". Each new team directly replaces the departing one, thereby maintaining a continual human presence on the island.[33][34]

A team normally consists of:

- A senior meteorologist

- Two junior meteorologists

- A radio technician

- A medic

- A diesel mechanic

- A number of biologists (depending on ongoing research projects)

The team is supplied with enough food to last the whole year. People and cargo are landed either by helicopter, from a helideck-equipped supply ship, or by a fixed crane atop a cliff near the station (a place aptly called "Crane Point").

In 2014 a member of the research team choked to death on the island and his body was taken back to South Africa.[35]

Maps

Relief map

Relief map Orthographic projection

Orthographic projection Satellite map

Satellite map

See also

- South African National Antarctic Programme – Government research programme

- SANAE – South African National Antarctic Expedition

- Marion Island – The larger of the Prince Edward Islands

- S. A. Agulhas – South African ice-strengthened training ship and former polar research vessel

- S. A. Agulhas II – Icebreaking polar supply and research ship

- Nigel Morritt Wace

References

- "Gough Island". Ramsar Sites Information Service. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- Report on the geological collections made during the voyage of the ... British Museum (Natural History), Walter Campbell Smith, British Museum (Natural History) – 1930 "DIEGO ALVAREZ OR GOUGH ISLAND. By W. Campbell Smith. Gough Island, as it seems to be more usually called, lies about 200 miles south of the Tristan da Cunha group in latitude 40° S., longitude 10° W.1 It is about 8 miles long by 3 ..."

- Plants of Gough Island: (Diego Alvarez) Erling Christophersen – 1934

- The Antarctic dictionary: a complete guide to Antarctic English – Page 150 Bernadette Hince – 2000 -"I went for adventure. to have fun, Gough Island Gough Island was named I. de Goncalo Alvarez on early maps. after its discoverer. Portuguese navigator Goncalo Alvarez. The name was later corrupted to I. Diego Alvarez. and there was confusion about the locality. It was renamed after Captain Charles Gough of the British barque Richmond. who sighted the island in 1713."

- Raymond John Howgego, Historical Encyclopedia of Atlantic Vigias, London, 2015

- "South African Journal of Science – Gough Island 500 years after its discovery: a bibliography of scientific and popular literature 1505 to 2005". Scielo.org.za. Retrieved 25 October 2012.

- Wace N.M. (1969). "The discovery, exploitation and settlement of the Tristan da Cunha Islands". Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society of Australasia (South Australian Branch). 10: 11–40.

- Capt. Francisco de Seixas y Lovera, Descripcion geographica, y derrotero de la region austral Magallanica. Que se dirige al Rey nuestro señor, gran monarca de España, y sus dominios en Europa, Emperador del Nuevo Mundo Americano, y Rey de los reynos de la Filipinas y Malucas, Madrid, Antonio de Zafra, 1690. (Relevant fragment)

- J.-F.G. de la Pérouse, F.A.M. de la Rúa. A Voyage Round the World, Performed in the Years 1785, 1786, 1787, and 1788, by the Boussole and Astrolabe: Under the Command of J.-F.G. de la Pérouse, Volume 1. London: Lackington, Allen, and Company, 1807. pp.71-81.

- Gough's log is preserved in the East India Collection at the British Library. The entry for 3 March 1732 is printed in Gabriel Wright (pub.), "A New Nautical Directory for the East-India and China Navigation", 7th edn, London, 1804, p. 394.

- Heaney, J.B., Holdgate, M.W. (1957). The Gough Island Scientific Survey. The Geographical Journal, Vol. 123, No. 1, pp. 20–31

- R.K. Headland (Ed.) Historical Antarctic Sealing Industry, Scott Polar Research Institute (University of Cambridge), 2018, p.176. ISBN 978-0-901021-26-7

- Headland, p.167.

- Rudmose Brown, R. N.; Pirie, J. H.; Mossman, R. C. (2002). The Voyage of the Scotia. Edinburgh: Mercat Press. pp. 132–34. ISBN 978-1-84183-044-5.

- Wild, Frank (1923). "Chapter XIII: Diego Alvarez or Gough Island". Shackleton's last voyage: The Story of the Quest. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- "Gough Island, South Atlantic Ocean". Btinternet.com. Archived from the original on 12 October 2012. Retrieved 25 October 2012.

- "Gough Island". Sanap.ac.za. Archived from the original on 12 September 2017. Retrieved 25 October 2012.

- Riffenburgh, Beau (20 May 2018). Encyclopedia of the Antarctic. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-97024-2 – via Google Books.

- "Gough Island Climate Normals 1961−1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- "Klimatafel von Gough Island / Südatlantik / Großbritannien" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961–1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- "Climate Statistics for Gough Island, South Africa". 20 February 1998. Archived from the original on 20 August 2016. Retrieved 7 March 2012.

- "Gough and Inaccessible Islands". UNESCO Organization. Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- Cuthbert, J. & Sommer, E. Population size and trends of four globally threatened seabirds at Gough Island, South Atlantic Ocean. Marine Ornithology 32: 97–103.

- Roots, Clive (2006). Flightless birds. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-313-33545-7. Retrieved 31 March 2008.

- "Gough Island". Important Bird Areas factsheet. BirdLife International. 2012. Retrieved 25 October 2012.

- Cooper, J. et al., "Earth, fire and water: applying novel techniques to eradicate the invasive plant, procumbent pearlwort Sagina procumbens, on Gough Island, a World Heritage Site in the South Atlantic", Invasive Species Specialist Group, 2010, Retrieved on 12 February 2014.

- Bisser, P. et al., "Strategies to eradicate the invasive plant procumbent pearlwort Sagina procumbens on Gough Island, 2010", Retrieved on 12 February 2014.

- R M Wanless; A Angel; R J Cuthbert; G M Hilton; P G Ryan (2007). "Can predation by invasive mice drive seabird extinctions?". Biology Letters. 3 (3): 241–244. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0120. PMC 2464706. PMID 17412667.

- Caravaggi, Anthony (22 October 2018). "The impacts of introduced House Mice on the breeding success of nesting seabirds on Gough Island". Ibis. IBIS International Journal of Avian Science. 161 (3): 648–661. doi:10.1111/ibi.12664.

- R. J. Cuthbert1 , P. Visser et al., "Preparations for the eradication of mice from Gough Island: results of bait acceptance trials above ground and around cave systems", 2011, Retrieved on 12 February 2014.

- Butchart, Stuart H. M.; Micol, Thierry; Cranwell, Steve; Pasachnik, Stesha A.; Wanless, Ross; Fisher, Robert N.; Griffiths, Richard; Pierce, Ray; Borroto-Páez, Rafael (27 March 2019). "Globally important islands where eradicating invasive mammals will benefit highly threatened vertebrates". PLOS ONE. 14 (3): e0212128. Bibcode:2019PLoSO..1412128H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0212128. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 6436766. PMID 30917126.

- Barkham, Patrick (28 June 2020). "Should we cull one species to save another?". The Guardian.

- "South Africa National Antarctic Programme - Gough Island Teams" Archived 12 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved 12 February 2014

- Chris Bell, "Chris Bell's Blog from Gough 58", Retrieved 12 February 2014

- "SA man dies on Gough Island". www.enca.com.

External links

- www.goughisland.com - The Gough Island Restoration Project website

- Gough Island Gallery

- Facebook Groups - Gough Island team discussions

- Gough and Inaccessible Islands - UNESCO wildlife reserve publication

- Photographs of Gough Island - Flickr publication by Chantal van Staden.