Thalassocracy

A thalassocracy or thalattocracy (from Classical Greek: θάλασσα, romanized: thalassa (Attic Greek: θάλαττα, romanized: thalatta) transl. 'sea', and Ancient Greek: κρατεῖν, romanized: kratein, lit. 'power'; giving Koinē Greek: θαλασσοκρατία, romanized: thalassokratia, lit. 'sea power') is a state with primarily maritime realms, an empire at sea, or a seaborne empire.[1] Traditional thalassocracies seldom dominate interiors, even in their home territories. Examples of this are the Phoenician states of Tyre, Sidon, and Carthage of the Mediterranean; the Chola dynasty of India and the Austronesian states of Srivijaya and Majapahit of Maritime Southeast Asia. Thalassocracies can thus be distinguished from traditional empires, where a state's territories, though possibly linked principally or solely by the sea lanes, generally extend into mainland interiors[2][3] in a tellurocracy ("land-based hegemony").[4]

The term thalassocracy can also simply refer to naval supremacy, in either military or commercial senses. The Ancient Greeks first used the word thalassocracy to describe the government of the Minoan civilization, whose power depended on its navy.[5] Herodotus distinguishes sea-power from land-power and spoke of the need to counter the Phoenician thalassocracy by developing a Greek "empire of the sea".[6]

History and examples of thalassocracies

Indo-Pacific

The Austronesian peoples of Maritime Southeast Asia, who built the first ocean-going ships,[8] developed the Indian Ocean's first true maritime trade network.[7] They established trade routes with Southern India and Sri Lanka as early as 1500 BC, ushering in an exchange of material culture (like catamarans, outrigger boats, lashed-lug and sewn-plank boats, and paan) and cultigens (like coconuts, sandalwood, bananas, and sugarcane); as well as connecting the material cultures of India and China. Indonesians in particular traded in spices (mainly cinnamon and cassia) with East Africa, using catamaran and outrigger boats and sailing with the help of the Westerlies in the Indian Ocean. This trade network expanded west to Africa and the Arabian Peninsula, resulting in the Austronesian colonization of Madagascar by the first half of the first millennium AD. It continued into historic times, later becoming the Maritime Silk Road.[7][9][10][11][12]

The first thalassocracies in the Indo-Pacific region began to emerge around the 2nd century AD, through the rise of emporia exploiting the prosperous trade routes between Funan and India through the Malacca Strait using advanced Austronesian sailing technologies. Numerous coastal city-states emerged, centered on trading ports built near or around river mouths which allowed easy access to goods from inland for maritime trade. These city-states established commercial networks with other trading centers in Southeast Asia and beyond. Their rulers also gradually Indianized by adopting the social structures and religions of India to consolidate their power.[13]

The thalassocratic empire of Srivijaya emerged by the 7th century through conquest and subjugation of neighboring thalassocracies. These included Melayu, Kedah, Tarumanagara, and Medang, among others. These polities controlled the sea lanes in Southeast Asia and exploited the spice trade of the Spice Islands, as well as maritime trade-routes between India and China.[13] Srivijaya was in turn subjugated by Singhasari around 1275, before finally being absorbed by the successor thalassocracy of Majapahit (1293–1527).[14]

Europe and the Mediterranean

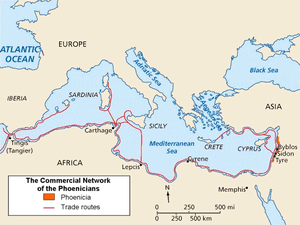

Phoenicia and the Delian League were early examples of Mediterannean thalassocracies.

The Middle Ages saw multiple thalassocracies, often land-based empires which controlled areas of the sea. Among the most famous were the Republic of Venice, the Republic of Genoa and the Republic of Pisa.

The Venetian republic was conventionally divided in the fifteenth century into the Dogado of Venice and the Lagoon, the Stato di Terraferma of Venetian holdings in northern Italy, and the Stato da Màr of the Venetian outlands bound by the sea. According to the French historian Fernand Braudel, Venice was a scattered empire, a trading-post empire forming a long capitalist antenna.[15]

The Early Middle Ages (c. 500 – 1000 AD) saw many of the coastal cities of the Mezzogiorno develop into minor thalassocracies whose chief powers lay in their ports and in their ability to sail navies to defend friendly coasts and to ravage enemy ones. These include the variously Byzantine and Lombard duchies of Gaeta, Naples, Salerno and Amalfi.

After 1000, some northern and central Italian city-states developed their own trade empires, in particular the republic based on Pisa and the powerful Republic of Genoa, that rivaled Venice. These three, along with Amalfi, Gaeta, Ancona, the small Republic of Noli and the Dalmatian Ragusa are known as maritime republics.[16]

With the modern age, the Age of Exploration saw some of the most formidable thalassocracies emerge. Anchored in their European territories, several nations established colonial empires held together by naval supremacy. First among them chronologically was the Portuguese Empire, followed soon by the Spanish Empire, which was challenged by the Dutch Empire, itself replaced on the high seas by the British Empire, whose landed possessions were immense and held together by the greatest navy of its time. With naval arms-races (especially between Germany and Britain), the end of colonialism, and the winning of independence by many colonies, European thalassocracies, which had controlled the world's oceans for centuries, diminished - though Britain's power-projection in the Falklands War of 1982 demonstrated continuing thalassocratic clout.

Transcontinental

The Ottoman Empire expanded from a land-based region to dominate the Eastern Mediterranean and to expand into the Indian Ocean as a thalassocracy from the 15th century AD.[17]

List of examples

- Crown of Aragon

- British Empire

- Bruneian Empire

- Ancient Carthage

- Chola Empire

- Dál Riata

- Delian League

- Sultanate of Demak

- Denmark-Norway

- Dorian Confederation

- Dutch Empire

- Frisian Kingdom

- Maritime republics

- Hanseatic League

- Empire of Japan

- Sultanate of Johor

- Kediri

- Kilwa Sultanate

- Kingdom of the Isles

- Kingdom of Norway (872–1397)

- Liburnia

- Majapahit Empire

- Mataram Kingdom

- Sultanate of Maguindanao

- Sultanate of Malacca

- Minoan civilization

- Muscat and Oman

- North Sea Empire

- Omani Empire

- Phoenicia

- Republic of Pirates

- Republic of Pisa

- Portuguese Empire

- Ryūkyū Kingdom

- Spanish Empire

- Swedish Empire

- Srivijaya

- Sultanate of Sulu

- Sultanate of Ternate

- Sultanate of Tidore

- Tu'i Tonga Empire

See also

- Archipelagic state

- Nomadic empire

- List of countries spanning more than one continent

- List of historical countries and empires spanning more than one continent

- Alfred Thayer Mahan

- Naval history

Notes

-

Alpers, Edward A. (2013). The Indian Ocean in World History. New Oxford World History. Oxford University Press. p. 80. ISBN 9780199929948. Retrieved 2016-02-06.

Portugal's was in every sense a seaborne empire or thalassocracy.

- P. M. Holt; Ann K. S. Lambton; Bernard Lewis (21 April 1977). The Cambridge History of Islam. Cambridge University Press. pp. 129–. ISBN 978-0-521-29137-8.

- Barbara Watson Andaya; Leonard Y. Andaya (19 February 2015). A History of Early Modern Southeast Asia, 1400–1830. Cambridge University Press. pp. 159–. ISBN 978-0-521-88992-6.

- Lukic, Rénéo; Brint, Michael, eds. (2001). Culture, politics, and nationalism in the age of globalization. Ashgate. p. 103. ISBN 9780754614364. Retrieved 2015-10-12.

- D. Abulafia, "Thalassocracies", in P. Horden – S. Kinoshita (eds.), A Companion to Mediterranean History, Oxford, 2014, pp. 139–153, here 139–140.

- A. Momigliano, "Sea-Power in Greek Thought", The Classical Review, May 1944, 1–7.

- Manguin, Pierre-Yves (2016). "Austronesian Shipping in the Indian Ocean: From Outrigger Boats to Trading Ships". In Campbell, Gwyn (ed.). Early Exchange between Africa and the Wider Indian Ocean World. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 51–76. ISBN 9783319338224.

- Meacham, Steve (11 December 2008). "Austronesians were first to sail the seas". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- Doran, Edwin, Jr. (1974). "Outrigger Ages". The Journal of the Polynesian Society. 83 (2): 130–140.

- Mahdi, Waruno (1999). "The Dispersal of Austronesian boat forms in the Indian Ocean". In Blench, Roger; Spriggs, Matthew (eds.). Archaeology and Language III: Artefacts, languages and texts (PDF). One World Archaeology. 34. Routledge. pp. 144–179. ISBN 0415100542.

- Doran, Edwin B. (1981). Wangka: Austronesian Canoe Origins. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 9780890961070.

- Blench, Roger (2004). "Fruits and arboriculture in the Indo-Pacific region". Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association. 24 (The Taipei Papers (Volume 2)): 31–50.

- Sulistiyono, Singgih Tri; Masruroh, Noor Naelil; Rochwulaningsih, Yety (2018). "Contest For Seascape: Local Thalassocracies and Sino-Indian Trade Expansion in the Maritime Southeast Asia During the Early Premodern Period". Journal of Marine and Island Cultures. 7 (2). doi:10.21463/jmic.2018.07.2.05.

- Kulke, Hermann (2016). "Śrīvijaya Revisited: Reflections on State Formation of a Southeast Asian Thalassocracy". Bulletin de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient. 102: 45–95.

- Fernand Braudel, The Perspective of the World, vol. III of Civilization and Capitalism (Harper & Row) 1984:119.

- Gino Benvenuti Le Repubbliche Marinare. Amalfi, Pisa, Genova, Venezia - Newton & Compton editori, Roma 1989; Armando Lodolini, Le repubbliche del mare, Biblioteca di storia patria, 1967, Roma.

-

Fattori, Niccolò (2019). "The Conquering Ottoman Merchant". Migration and Community in the Early Modern Mediterranean: The Greeks of Ancona, 1510-1595. Palgrave Studies in Migration History. Cham (Zug): Springer. p. 44. ISBN 9783030169046. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

The rise of an Ottoman thalassocracy over the eastern half of the Mediterranean [...].