Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. The term is similar to the idea of a senate, synod or congress, and is commonly used in countries that are current or former monarchies, a form of government with a monarch as the head. Some contexts restrict the use of the word parliament to parliamentary systems, although it is also used to describe the legislature in some presidential systems (e.g. the Parliament of Ghana), even where it is not in the official name.

Historically, parliaments included various kinds of deliberative, consultative, and judicial assemblies, e.g. medieval parliaments.

Etymology

The English term is derived from Anglo-Norman and dates to the 14th century, coming from the 11th century Old French parlement, from parler, meaning "to talk".[2] The meaning evolved over time, originally referring to any discussion, conversation, or negotiation through various kinds of deliberative or judicial groups, often summoned by a monarch. By the 15th century, in Britain, it had come to specifically mean the legislature.[3]

Early parliaments

Since ancient times, when societies were tribal, there were councils or a headman whose decisions were assessed by village elders. This is called tribalism.[4] Some scholars suggest that in ancient Mesopotamia there was a primitive democratic government where the kings were assessed by council.[5] The same has been said about ancient India, where some form of deliberative assemblies existed, and therefore there was some form of democracy.[6] However, these claims are not accepted by most scholars, who see these forms of government as oligarchies.[7][8][9][10][11]

Ancient Athens was the cradle of democracy.[12] The Athenian assembly (ἐκκλησία, ekklesia) was the most important institution, and every free male citizen could take part in the discussions. Slaves and women could not. However, Athenian democracy was not representative, but rather direct, and therefore the ekklesia was different from the parliamentary system.

The Roman Republic had legislative assemblies, who had the final say regarding the election of magistrates, the enactment of new statutes, the carrying out of capital punishment, the declaration of war and peace, and the creation (or dissolution) of alliances.[13] The Roman Senate controlled money, administration, and the details of foreign policy.[14]

Some Muslim scholars argue that the Islamic shura (a method of taking decisions in Islamic societies) is analogous to the parliament.[15] However, others highlight what they consider fundamental differences between the shura system and the parliamentary system.[16][17][18]

Iran

The first recorded signs of a council to decide on different issues in ancient Iran dates back to 247 BC while the Parthian empire was in power. The Parthians established the first Iranian empire since the conquest of Persia by Alexander. In the early years of their rule, an assembly of the nobles called “Mehestan” was formed that made the final decision on serious issues of state.[19]

The word "Mehestan" consists of two parts. "Meh", a word of the old Persian origin, which literally means "The Great" and "-Stan", a suffix in the Persian language, which describes an especial place. Altogether Mehestan means a place where the greats come together.[20]

The Mehestan Assembly, which consisted of Zoroastrian religious leaders and clan elders exerted great influence over the administration of the kingdom.[21]

One of the most important decisions of the council took place in 208 AD, when a civil war broke out and the Mehestan decided that the empire would be ruled by two brothers simultaneously, Ardavan V and Blash V.[22] In 224 AD, following the dissolution of the Parthian empire, after over 470 years, the Mahestan council came to an end.

Spain

Although there are documented councils held in 873, 1020, 1050 and 1063, there was no representation of commoners. What is considered to be the first parliament (with the presence of commoners), the Cortes of León, was held in the Kingdom of León in 1188.[23][24][25] According to the UNESCO, the Decreta of Leon of 1188 is the oldest documentary manifestation of the European parliamentary system. In addition, UNESCO granted the 1188 Cortes of Alfonso IX the title of "Memory of the World" and the city of Leon has been recognized as the "Cradle of Parliamentarism".[26][27]

After coming to power, King Alfonso IX, facing an attack by his two neighbors, Castile and Portugal, decided to summon the "Royal Curia". This was a medieval organization composed of aristocrats and bishops but because of the seriousness of the situation and the need to maximize political support, Alfonso IX took the decision to also call the representatives of the urban middle class from the most important cities of the kingdom to the assembly.[28] León's Cortes dealt with matters like the right to private property, the inviolability of domicile, the right to appeal to justice opposite the King and the obligation of the King to consult the Cortes before entering a war.[29] Prelates, nobles and commoners met separately in the three estates of the Cortes. In this meeting, new laws were approved to protect commoners against the arbitrarities of nobles, prelates and the king. This important set of laws is known as the Carta Magna Leonesa.

Following this event, new Cortes would appear in the other different territories that would make up Spain: Principality of Catalonia in 1192, the Kingdom of Castile in 1250, Kingdom of Aragon in 1274, Kingdom of Valencia in 1283 and Kingdom of Navarre in 1300.

After the union of the Kingdoms of Leon and Castile under the Crown of Castile, their Cortes were united as well in 1258. The Castilian Cortes had representatives from Burgos, Toledo, León, Seville, Córdoba, Murcia, Jaén, Zamora, Segovia, Ávila, Salamanca, Cuenca, Toro, Valladolid, Soria, Madrid, Guadalajara and Granada (after 1492). The Cortes' assent was required to pass new taxes, and could also advise the king on other matters. The comunero rebels intended a stronger role for the Cortes, but were defeated by the forces of Habsburg Emperor Charles V in 1521. The Cortes maintained some power, however, though it became more of a consultative entity. However, by the time of King Philip II, Charles's son, the Castilian Cortes had come under functionally complete royal control, with its delegates dependent on the Crown for their income.[30]

The Cortes of the Crown of Aragon kingdoms retained their power to control the king's spending with regard to the finances of those kingdoms. But after the War of the Spanish Succession and the victory of another royal house – the Bourbons – and King Philip V, their Cortes were suppressed (those of Aragon and Valencia in 1707, and those of Catalonia and the Balearic islands in 1714).

The very first Cortes representing the whole of Spain (and the Spanish empire of the day) assembled in 1812, in Cadiz, where it operated as a government in exile as at that time most of the rest of Spain was in the hands of Napoleon's army.

Portugal

After its self-proclamation as an independent kingdom in 1139 by Afonso I of Portugal (followed by the recognition by the Kingdom of León in the Treaty of Zamora of 1143), the first historically established Cortes of the Kingdom of Portugal occurred in 1211 in Coimbra by initiative of Afonso II of Portugal. These established the first general laws of the kingdom (Leis Gerais do Reino): protection of the king's property, stipulation of measures for the administration of justice and the rights of his subjects to be protected from abuses by royal officials, and confirming the clerical donations of the previous king Sancho I of Portugal. These Cortes also affirmed the validity of canon law for the Church in Portugal, while introducing the prohibition of the purchase of lands by churches or monasteries (although they can be acquired by donations and legacies).

After the conquest of Algarve in 1249, the Kingdom of Portugal completed its Reconquista. In 1254 King Afonso III of Portugal summoned Portuguese Cortes in Leiria, with the inclusion of burghers from old and newly incorporated municipalities. This inclusion establishes the Cortes of Leiria of 1254 as the second sample of modern parliamentarism in the history of Europe (after the Cortes of León in 1188). In these Cortes the monetagio was introduced: a fixed sum was to be paid by the burghers to the Crown as a substitute for the septennium (the traditional revision of the face value of coinage by the Crown every seven years). These Cortes also introduced staple laws on the Douro River, favoring the new royal city of Vila Nova de Gaia at the expense of the old episcopal city of Porto.

The Portuguese Cortes met again under King Afonso III of Portugal in 1256, 1261 and 1273, always by royal summon. Medieval Kings of Portugal continued to rely on small assemblies of notables, and only summoned the full Cortes on extraordinary occasions. A Cortes would be called if the king wanted to introduce new taxes, change some fundamental laws, announce significant shifts in foreign policy (e.g. ratify treaties), or settle matters of royal succession, issues where the cooperation and assent of the towns was thought necessary. Changing taxation (especially requesting war subsidies), was probably the most frequent reason for convening the Cortes. As the nobles and clergy were largely tax-exempt, setting taxation involved intensive negotiations between the royal council and the burgher delegates at the Cortes.

Delegates (procuradores) not only considered the king's proposals, but, in turn, also used the Cortes to submit petitions of their own to the royal council on a myriad of matters, e.g. extending and confirming town privileges, punishing abuses of officials, introducing new price controls, constraints on Jews, pledges on coinage, etc. The royal response to these petitions became enshrined as ordinances and statutes, thus giving the Cortes the aspect of a legislature. These petitions were originally referred to as aggravamentos (grievances) then artigos (articles) and eventually capitulos (chapters). In a Cortes-Gerais, petitions were discussed and voted upon separately by each estate and required the approval of at least two of the three estates before being passed up to the royal council. The proposal was then subject to royal veto (either accepted or rejected by the king in its entirety) before becoming law.

Nonetheless, the exact extent of Cortes power was ambiguous. Kings insisted on their ancient prerogative to promulgate laws independently of the Cortes. The compromise, in theory, was that ordinances enacted in Cortes could only be modified or repealed by Cortes. But even that principle was often circumvented or ignored in practice.

The Cortes probably had their heyday in the 14th and 15th centuries, reaching their apex when John I of Portugal relied almost wholly upon the bourgeoisie for his power. For a period after the 1383–1385 Crisis, the Cortes were convened almost annually. But as time went on, they became less important. Portuguese monarchs, tapping into the riches of the Portuguese empire overseas, grew less dependent on Cortes subsidies and convened them less frequently. John II (r.1481-1495) used them to break the high nobility, but dispensed with them otherwise. Manuel I (r.1495-1521) convened them only four times in his long reign. By the time of Sebastian (r.1554–1578), the Cortes was practically an irrelevance.

Curiously, the Cortes gained a new importance with the Iberian Union of 1581, finding a role as the representative of Portuguese interests to the new Habsburg monarch. The Cortes played a critical role in the 1640 Restoration, and enjoyed a brief period of resurgence during the reign of John IV of Portugal (r.1640-1656). But by the end of the 17th century, it found itself sidelined once again. The last Cortes met in 1698, for the mere formality of confirming the appointment of Infante John (future John V of Portugal) as the successor of Peter II of Portugal. Thereafter, Portuguese kings ruled as absolute monarchs and no Cortes were assembled for over a century. This state of affairs came to an end with the Liberal Revolution of 1820, which set in motion the introduction of a new constitution, and a permanent and proper parliament, that however inherited the name of Cortes Gerais.

England

Early forms of assembly

England has long had a tradition of a body of men who would assist and advise the king on important matters. Under the Anglo-Saxon kings, there was an advisory council, the Witenagemot. The name derives from the Old English ƿitena ȝemōt, or witena gemōt, for "meeting of wise men". The first recorded act of a witenagemot was the law code issued by King Æthelberht of Kent ca. 600, the earliest document which survives in sustained Old English prose; however, the witan was certainly in existence long before this time.[31] The Witan, along with the folkmoots (local assemblies), is an important ancestor of the modern English parliament.[32]

As part of the Norman Conquest of England, the new king, William I, did away with the Witenagemot, replacing it with a Curia Regis ("King's Council"). Membership of the Curia was largely restricted to the tenants in chief, the few nobles who "rented" great estates directly from the king, along with ecclesiastics. William brought to England the feudal system of his native Normandy, and sought the advice of the curia regis before making laws. This is the original body from which the Parliament, the higher courts of law, and the Privy Council and Cabinet descend. Of these, the legislature is formally the High Court of Parliament; judges sit in the Supreme Court of Judicature. Only the executive government is no longer conducted in a royal court.

Most historians date the emergence of a parliament with some degree of power to which the throne had to defer no later than the rule of Edward I.[33] Like previous kings, Edward called leading nobles and church leaders to discuss government matters, especially finance and taxation. A meeting in 1295 became known as the Model Parliament because it set the pattern for later Parliaments. The significant difference between the Model Parliament and the earlier Curia Regis was the addition of the Commons; that is, the inclusion of elected representatives of rural landowners and of townsmen. In 1307, Edward I agreed not to collect certain taxes without the "consent of the realm" through parliament. He also enlarged the court system.

Magna Carta and the Model Parliament

.jpg)

The tenants-in-chief often struggled with their spiritual counterparts and with the king for power. In 1215, they secured from King John of England Magna Carta, which established that the king may not levy or collect any taxes (except the feudal taxes to which they were hitherto accustomed), save with the consent of a council. It was also established that the most important tenants-in-chief and ecclesiastics be summoned to the council by personal writs from the sovereign, and that all others be summoned to the council by general writs from the sheriffs of their counties. Modern government has its origins in the Curia Regis; parliament descends from the Great Council later known as the parliamentum established by Magna Carta.

During the reign of King Henry III, 13th-Century English Parliaments incorporated elected representatives from shires and towns. These parliaments are, as such, considered forerunners of the modern parliament.[34]

In 1265, Simon de Montfort, then in rebellion against Henry III, summoned a parliament of his supporters without royal authorization. The archbishops, bishops, abbots, earls, and barons were summoned, as were two knights from each shire and two burgesses from each borough. Knights had been summoned to previous councils, but it was unprecedented for the boroughs to receive any representation. Come 1295, Edward I later adopted de Montfort's ideas for representation and election in the so-called "Model Parliament". At first, each estate debated independently; by the reign of Edward III, however, Parliament recognisably assumed its modern form, with authorities dividing the legislative body into two separate chambers.

Parliament under Henry VIII and Edward VI

The purpose and structure of Parliament in Tudor England underwent a significant transformation under the reign of Henry VIII. Originally its methods were primarily medieval, and the monarch still possessed a form of inarguable dominion over its decisions. According to Elton, it was Thomas Cromwell, 1st Earl of Essex, then chief minister to Henry VIII, who initiated still other changes within parliament.

The Reformation Acts supplied Parliament with unlimited power over the country. This included authority over virtually every matter, whether social, economic, political, or religious ; it legalised the Reformation, officially and indisputably. The king had to rule through the council, not over it, and all sides needed to reach a mutual agreement when creating or passing laws, adjusting or implementing taxes, or changing religious doctrines. This was significant: the monarch no longer had sole control over the country. For instance, during the later years of Mary, Parliament exercised its authority in originally rejecting Mary's bid to revive Catholicism in the realm. Later on, the legislative body even denied Elizabeth her request to marry . If Parliament had possessed this power before Cromwell, such as when Wolsey served as secretary, the Reformation may never have happened, as the king would have had to gain the consent of all parliament members before so drastically changing the country's religious laws and fundamental identity .

The power of Parliament increased considerably after Cromwell's adjustments. It also provided the country with unprecedented stability. More stability, in turn, helped assure more effective management, organisation, and efficiency. Parliament printed statutes and devised a more coherent parliamentary procedure.

The rise of Parliament proved especially important in the sense that it limited the repercussions of dynastic complications that had so often plunged England into civil war. Parliament still ran the country even in the absence of suitable heirs to the throne, and its legitimacy as a decision-making body reduced the royal prerogatives of kings like Henry VIII and the importance of their whims. For example, Henry VIII could not simply establish supremacy by proclamation; he required Parliament to enforce statutes and add felonies and treasons. An important liberty for Parliament was its freedom of speech; Henry allowed anything to be spoken openly within Parliament and speakers could not face arrest – a fact which they exploited incessantly. Nevertheless, Parliament in Henry VIII's time offered up very little objection to the monarch's desires. Under his and Edward's reign, the legislative body complied willingly with the majority of the kings' decisions.

Much of this compliance stemmed from how the English viewed and traditionally understood authority. As Williams described it, "King and parliament were not separate entities, but a single body, of which the monarch was the senior partner and the Lords and the Commons the lesser, but still essential, members.".

Importance of the Commonwealth years

Although its role in government expanded significantly during the reigns of Henry VIII and Edward VI, the Parliament of England saw some of its most important gains in the 17th century. A series of conflicts between the Crown and Parliament culminated in the execution of King Charles I in 1649. Afterward, England became a commonwealth, with Oliver Cromwell, its lord protector, the de facto ruler. Frustrated with its decisions, Cromwell purged and suspended Parliament on several occasions.

A controversial figure accused of despotism, war crimes, and even genocide, Cromwell is nonetheless regarded as essential to the growth of democracy in England.[35] The years of the Commonwealth, coupled with the restoration of the monarchy in 1660 and the subsequent Glorious Revolution of 1688, helped reinforce and strengthen Parliament as an institution separate from the Crown.

Acts of Union

The Parliament of England met until it merged with the Parliament of Scotland under the Acts of Union. This union created the new Parliament of Great Britain in 1707.

Scotland

From the 10th century the Kingdom of Alba was ruled by chiefs (toisechs) and subkings (mormaers) under the suzerainty, real or nominal, of a High King. Popular assemblies, as in Ireland, were involved in law-making, and sometimes in king-making, although the introduction of tanistry—naming a successor in the lifetime of a king—made the second less than common. These early assemblies cannot be considered "parliaments" in the later sense of the word, and were entirely separate from the later, Norman-influenced, institution.

The Parliament of Scotland evolved during the Middle Ages from the King's Council of Bishops and Earls. The unicameral parliament is first found on record, referred to as a colloquium, in 1235 at Kirkliston (a village now in Edinburgh).

By the early fourteenth century the attendance of knights and freeholders had become important, and from 1326 burgh commissioners attended. Consisting of the Three Estates; of clerics, lay tenants-in-chief and burgh commissioners sitting in a single chamber, the Scottish parliament acquired significant powers over particular issues. Most obviously it was needed for consent for taxation (although taxation was only raised irregularly in Scotland in the medieval period), but it also had a strong influence over justice, foreign policy, war, and all manner of other legislation, whether political, ecclesiastical, social or economic. Parliamentary business was also carried out by "sister" institutions, before c. 1500 by General Council and thereafter by the Convention of Estates. These could carry out much business also dealt with by Parliament – taxation, legislation and policy-making – but lacked the ultimate authority of a full parliament.

The parliament, which is also referred to as the Estates of Scotland, the Three Estates, the Scots Parliament or the auld Scots Parliament (Eng: old), met until the Acts of Union merged the Parliament of Scotland and the Parliament of England, creating the new Parliament of Great Britain in 1707.

Following the 1997 Scottish devolution referendum, and the passing of the Scotland Act 1998 by the Parliament of the United Kingdom, the Scottish Parliament was reconvened on 1 July 1999, although with much more limited powers than its 18th-century predecessor. The parliament has sat since 2004 at its newly constructed Scottish Parliament Building in Edinburgh, situated at the foot of the Royal Mile, next to the royal palace of Holyroodhouse.

Nordic and Germanic countries

A thing or ting (Old Norse and Icelandic: þing; other modern Scandinavian: ting, ding in Dutch) was the governing assembly in Germanic societies, made up of the free men of the community and presided by lawspeakers.

The thing was the assembly of the free men of a country, province or a hundred (hundare/härad/herred). There were consequently, hierarchies of things, so that the local things were represented at the thing for a larger area, for a province or land. At the thing, disputes were solved and political decisions were made. The place for the thing was often also the place for public religious rites and for commerce.

The thing met at regular intervals, legislated, elected chieftains and kings, and judged according to the law, which was memorised and recited by the "law speaker" (the judge).

The Icelandic, Faroese and Manx parliaments trace their origins back to the Viking expansion originating from the Petty kingdoms of Norway as well as Denmark, replicating Viking government systems in the conquered territories, such as those represented by the Gulating near Bergen in western Norway.

- The Icelandic Althing, dating to 930.[36]

- The Faroese Løgting, dating to a similar period.[37]

- The Manx Tynwald, which claims to be over 1,000 years old.[38][39][40]

Later national diets with chambers for different estates developed, e.g. in Sweden and in Finland (which was part of Sweden until 1809), each with a House of Knights for the nobility. In both these countries, the national parliaments are now called riksdag (in Finland also eduskunta), a word used since the Middle Ages and equivalent of the German word Reichstag.

Today the term lives on in the official names of national legislatures, political and judicial institutions in the North-Germanic countries. In the Yorkshire and former Danelaw areas of England, which were subject to much Norse invasion and settlement, the wapentake was another name for the same institution.

Italy

The Sicilian Parliament, dating to 1097, evolved as the legislature of the Kingdom of Sicily.[41][42]

Switzerland

The Federal Diet of Switzerland was one of the longest-lived representative bodies in history, continuing from the 13th century to 1848.

France

Originally, there was only the Parliament of Paris, born out of the Curia Regis in 1307, and located inside the medieval royal palace, now the Paris Hall of Justice. The jurisdiction of the Parliament of Paris covered the entire kingdom. In the thirteenth century, judicial functions were added. In 1443, following the turmoil of the Hundred Years' War, King Charles VII of France granted Languedoc its own parliament by establishing the Parliament of Toulouse, the first parliament outside of Paris, whose jurisdiction extended over the most part of southern France. From 1443 until the French Revolution several other parliaments were created in some provinces of France (Grenoble, Bordeaux).

All the parliaments could issue regulatory decrees for the application of royal edicts or of customary practices; they could also refuse to register laws that they judged contrary to fundamental law or simply as being untimely. Parliamentary power in France was suppressed more so than in England as a result of absolutism, and parliaments were eventually overshadowed by the larger Estates General, up until the French Revolution, when the National Assembly became the lower house of France's bicameral legislature.

Poland

According to the Chronicles of Gallus Anonymus, the first legendary Polish ruler, Siemowit, who began the Piast Dynasty, was chosen by a wiec. The veche (Russian: вече, Polish: wiec) was a popular assembly in medieval Slavic countries, and in late medieval period, a parliament. The idea of the wiec led in 1182 to the development of the Polish parliament, the Sejm.

The term "sejm" comes from an old Polish expression denoting a meeting of the populace. The power of early sejms grew between 1146–1295, when the power of individual rulers waned and various councils and wiece grew stronger. The history of the national Sejm dates back to 1182. Since the 14th century irregular sejms (described in various Latin sources as contentio generalis, conventio magna, conventio solemna, parlamentum, parlamentum generale, dieta or Polish sejm walny) have been called by Polish kings. From 1374, the king had to receive sejm permission to raise taxes. The General Sejm (Polish Sejm Generalny or Sejm Walny), first convoked by the king John I Olbracht in 1493 near Piotrków, evolved from earlier regional and provincial meetings (sejmiks). It followed most closely the sejmik generally, which arose from the 1454 Nieszawa Statutes, granted to the szlachta (nobles) by King Casimir IV the Jagiellonian. From 1493 forward, indirect elections were repeated every two years. With the development of the unique Polish Golden Liberty the Sejm's powers increased.

The Commonwealth's general parliament consisted of three estates: the King of Poland (who also acted as the Grand Duke of Lithuania, Russia/Ruthenia, Prussia, Mazovia, etc.), the Senat (consisting of Ministers, Palatines, Castellans and Bishops) and the Chamber of Envoys—circa 170 nobles (szlachta) acting on behalf of their Lands and sent by Land Parliaments. Also representatives of selected cities but without any voting powers. Since 1573 at a royal election all peers of the Commonwealth could participate in the Parliament and become the King's electors.

Ukraine

Cossack Rada was the legislative body of a military republic of the Ukrainian Cossacks that grew rapidly in the 15th century from serfs fleeing the more controlled parts of the Polish Lithuanian Commonwealth. The republic did not regard social origin/nobility and accepted all people who declared to be Orthodox Christians.

Originally established at the Zaporizhian Sich, the rada (council) was an institution of Cossack administration in Ukraine from the 16th to the 18th century. With the establishment of the Hetman state in 1648, it was officially known as the General Military Council until 1750.

Russia

The zemsky sobor (Russian: зе́мский собо́р) was the first Russian parliament of the feudal Estates type, in the 16th and 17th centuries. The term roughly means assembly of the land.

It could be summoned either by tsar, or patriarch, or the Boyar Duma. Three categories of population, comparable to the Estates-General of France but with the numbering of the first two Estates reversed, participated in the assembly:

Nobility and high bureaucracy, including the Boyar Duma

The Holy Sobor of high Orthodox clergy

Representatives of merchants and townspeople (third estate)

The name of the parliament of nowadays Russian Federation is the Federal Assembly of Russia. The term for its lower house, State Duma (which is better known than the Federal Assembly itself, and is often mistaken for the entirety of the parliament) comes from the Russian word думать (dumat), "to think". The Boyar Duma was an advisory council to the grand princes and tsars of Muscovy. The Duma was discontinued by Peter the Great, who transferred its functions to the Governing Senate in 1711.

Novgorod and Pskov

The veche was the highest legislature and judicial authority in the republic of Novgorod until 1478. In its sister state, Pskov, a separate veche operated until 1510.

Since the Novgorod revolution of 1137 ousted the ruling grand prince, the veche became the supreme state authority. After the reforms of 1410, the veche was restructured on a model similar to that of Venice, becoming the Commons chamber of the parliament. An upper Senate-like Council of Lords was also created, with title membership for all former city magistrates. Some sources indicate that veche membership may have become full-time, and parliament deputies were now called vechniks. It is recounted that the Novgorod assembly could be summoned by anyone who rung the veche bell, although it is more likely that the common procedure was more complex. This bell was a symbol of republican sovereignty and independence. The whole population of the city—boyars, merchants, and common citizens—then gathered at Yaroslav's Court. Separate assemblies could be held in the districts of Novgorod. In Pskov the veche assembled in the court of the Trinity cathedral.

Roman Catholic Church

"Conciliarism" or the "conciliar movement", was a reform movement in the 14th and 15th century Roman Catholic Church which held that final authority in spiritual matters resided with the Roman Church as corporation of Christians, embodied by a general church council, not with the pope. In effect, the movement sought – ultimately, in vain – to create an All-Catholic Parliament. Its struggle with the Papacy had many points in common with the struggle of parliaments in specific countries against the authority of Kings and other secular rulers.

Development of modern parliaments

The development of the modern concept of parliamentary government dates back to the Kingdom of Great Britain (1707–1800) and the parliamentary system in Sweden during the Age of Liberty (1718–1772).

United Kingdom

The British Parliament is often referred to as the Mother of Parliaments (in fact a misquotation of John Bright, who remarked in 1865 that "England is the Mother of Parliaments") because the British Parliament has been the model for most other parliamentary systems, and its Acts have created many other parliaments.[46] Many nations with parliaments have to some degree emulated the British "three-tier" model. Most countries in Europe and the Commonwealth have similarly organised parliaments with a largely ceremonial head of state who formally opens and closes parliament, a large elected lower house and a smaller, upper house.[47][48]

The Parliament of Great Britain was formed in 1707 by the Acts of Union that replaced the former parliaments of England and Scotland. A further union in 1801 united the Parliament of Great Britain and the Parliament of Ireland into a Parliament of the United Kingdom.

In the United Kingdom, Parliament consists of the House of Commons, the House of Lords, and the Monarch. The House of Commons is composed of 650 (soon to be 600) members who are directly elected by British citizens to represent single-member constituencies. The leader of a Party that wins more than half the seats, or less than half but is able to gain the support of smaller parties to achieve a majority in the house is invited by the Monarch to form a government. The House of Lords is a body of long-serving, unelected members: Lords Temporal – 92 of whom inherit their titles (and of whom 90 are elected internally by members of the House to lifetime seats), 588 of whom have been appointed to lifetime seats, and Lords Spiritual – 26 bishops, who are part of the house while they remain in office.

Legislation can originate from either the Lords or the Commons. It is voted on in several distinct stages, called readings, in each house. First reading is merely a formality. Second reading is where the bill as a whole is considered. Third reading is detailed consideration of clauses of the bill.

In addition to the three readings a bill also goes through a committee stage where it is considered in great detail. Once the bill has been passed by one house it goes to the other and essentially repeats the process. If after the two sets of readings there are disagreements between the versions that the two houses passed it is returned to the first house for consideration of the amendments made by the second. If it passes through the amendment stage Royal Assent is granted and the bill becomes law as an Act of Parliament.

The House of Lords is the less powerful of the two houses as a result of the Parliament Acts 1911 and 1949. These Acts removed the veto power of the Lords over a great deal of legislation. If a bill is certified by the Speaker of the House of Commons as a money bill (i.e. acts raising taxes and similar) then the Lords can only block it for a month. If an ordinary bill originates in the Commons the Lords can only block it for a maximum of one session of Parliament. The exceptions to this rule are things like bills to prolong the life of a Parliament beyond five years.

In addition to functioning as the second chamber of Parliament, the House of Lords was also the final court of appeal for much of the law of the United Kingdom—a combination of judicial and legislative function that recalls its origin in the Curia Regis. This changed in October 2009 when the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom opened and acquired the former jurisdiction of the House of Lords.

Since 1999, there has been a Scottish Parliament in Edinburgh, and, since 2020, a Welsh Parliament—or Senedd—in Cardiff. However, these national, unicameral legislatures do not have complete power over their respective countries of the United Kingdom, holding only those powers devolved to them by Westminster from 1997. They cannot legislate on defence issues, currency, or national taxation (e.g. VAT, or Income Tax). Additionally, the bodies can be dissolved, at any given time, by the British Parliament without the consent of the devolved government.

Sweden

In Sweden, the half-century period of parliamentary government beginning with Charles XII's death in 1718 and ending with Gustav III's self-coup in 1772 is known as the Age of Liberty. During this period, civil rights were expanded and power shifted from the monarch to parliament.

While suffrage did not become universal, the taxed peasantry was represented in Parliament, although with little influence and commoners without taxed property had no suffrage at all.

Parliamentary system

Many parliaments are part of a parliamentary system of government, in which the executive is constitutionally answerable to the parliament. Some restrict the use of the word parliament to parliamentary systems, while others use the word for any elected legislative body. Parliaments usually consist of chambers or houses, and are usually either bicameral or unicameral although more complex models exist, or have existed (see Tricameralism).

In some parliamentary systems, the prime minister is a member of the parliament (e.g. in the United Kingdom), whereas in others they are not (e.g. in the Netherlands). They are commonly the leader of the majority party in the lower house of parliament, but only hold the office as long as the "confidence of the house" is maintained. If members of the lower house lose faith in the leader for whatever reason, they can call a vote of no confidence and force the prime minister to resign.

This can be particularly dangerous to a government when the distribution of seats among different parties is relatively even, in which case a new election is often called shortly thereafter. However, in case of general discontent with the head of government, their replacement can be made very smoothly without all the complications that it represents in the case of a presidential system.

The parliamentary system can be contrasted with a presidential system, such as the American congressional system, which operates under a stricter separation of powers, whereby the executive does not form part of, nor is it appointed by, the parliamentary or legislative body. In such a system, congresses do not select or dismiss heads of governments, and governments cannot request an early dissolution as may be the case for parliaments. Some states, such as France, have a semi-presidential system which falls between parliamentary and congressional systems, combining a powerful head of state (president) with a head of government, the prime minister, who is responsible to parliament.

List of national parliaments

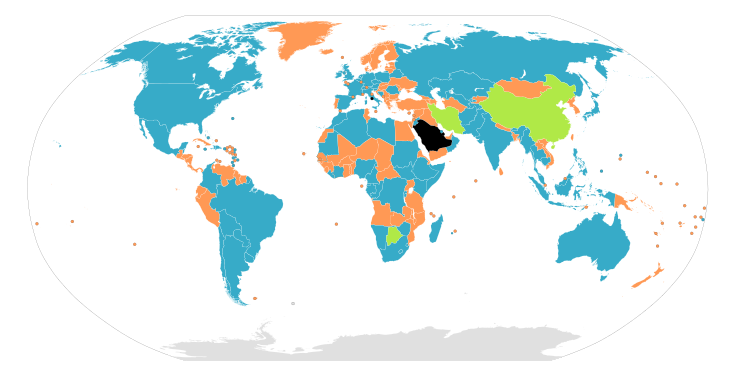

.jpg)

.jpg)

Parliaments of the European Union

- European Parliament

- Parliament of Austria (consisting of the National Council and the Federal Council)

- Belgian Federal Parliament (consisting of the Chamber of Representatives and the Senate)

- National Assembly of Bulgaria

- Croatian Parliament

- House of Representatives (Cyprus)

- Parliament of the Czech Republic (consisting of the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate)

- Folketing (Denmark)

- Riigikogu (Estonia)

- Parliament of Finland (Eduskunta)

- Parliament of France (consisting of the National Assembly and the Senate)

- Bundestag and Bundesrat (Germany)

- Hellenic Parliament (Greece)

- National Assembly (Hungary)

- Oireachtas (Ireland) (consisting of the President of Ireland, Dáil Éireann (Lower House) and Seanad Éireann (Senate))

- Parliament of Italy (consisting of the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate)

- Saeima (Latvia)

- Seimas (Lithuania)

- Chamber of Deputies (Luxembourg)

- House of Representatives (Malta)

- States General of the Netherlands (consisting of the House of Representatives and the Senate)

- National Assembly of the Republic of Poland (consisting of the Sejm and the Senate)

- Assembly of the Republic (Portugal)

- Parliament of Romania (consisting of the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate)

- National Council (Slovakia)

- Parliament of Slovenia (consisting of the National Assembly and the National Council)

- Cortes Generales (Spain) (consisting of the Congress of Deputies and the Senate)

- Riksdag (Sweden)

Others

- Parliament of Albania

- Parliament of Australia (consisting of the Queen, the House of Representatives, and the Senate)

- The federal government of the Commonwealth of Australia has a bicameral parliament and each of Australia's six states has a bicameral parliament except for Queensland, which has a unicameral parliament.

- Parliament of The Bahamas

- Jatiya Sangsad (Bangladesh)

- Parliament of Barbados

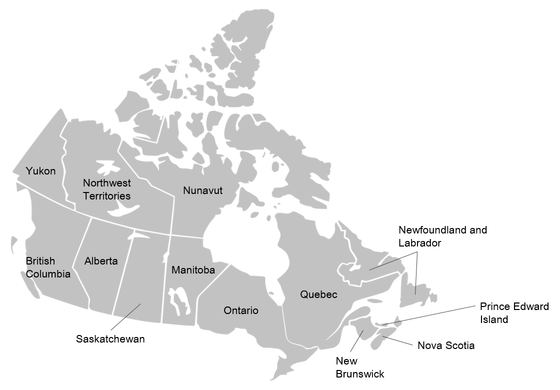

- Parliament of Canada (consisting of the Queen, an Upper House styled the Senate, and the House of Commons)

- The federal government of Canada has a bicameral parliament, and each of Canada's 10 provinces has a unicameral parliament.

- National People's Congress of the People's Republic of China

- Løgtingið (Faroe Islands)

- Parliament of Fiji

- Parliament of Ghana

- Legislative Council of Hong Kong

- Alþing (Parliament of Iceland) - Oldest surviving parliament

- Parliament of India (consisting of the Lok Sabha and the Rajya Sabha)

- Council of Representatives of Iraq

- National Diet of Japan (consisting of the House of Representatives and the House of Councillors)

- Parliament of Lebanon

- Parliament of the Isle of Man – Tynwald

- Parliament of Malaysia

- Parliament of Montenegro

- Parliament of Morocco

- Parliament of Nauru

- Parliament of Nepal (recently reorganised)

- Parliament of New Zealand (consisting of the Queen and House of Representatives)

- Assembly of the Republic of North Macedonia

- Parliament of Norway (Storting)

- Majlis-e-Shoora, Pakistan

- National Assembly of Serbia

- Parliament of Singapore

- Parliament of South Africa

- Parliament of Sri Lanka

- Legislative Yuan of Taiwan

- National Assembly of Thailand

- Parliament of the Central Tibetan Administration

- Parliament of Trinidad and Tobago

- Grand National Assembly of Turkey

- Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine

- Parliament of Zimbabwe

List of subnational parliaments

Australia

Australia's States and territories:

Belgium

In the federal (bicameral) kingdom of Belgium, there is a curious asymmetrical constellation serving as directly elected legislatures for three "territorial" regions—Flanders (Dutch), Brussels (bilingual, certain peculiarities of competence, also the only region not comprising any of the 10 provinces) and Wallonia (French)—and three cultural communities—Flemish (Dutch, competent in Flanders and for the Dutch-speaking inhabitants of Brussels), Francophone (French, for Wallonia and for Francophones in Brussels) and German (for speakers of that language in a few designated municipalities in the east of the Walloon Region, living alongside Francophones but under two different regimes):

- Flemish Parliament serves both the Flemish Community and the region of Flanders (in all matters of regional competence, its decisions have no effect in Brussels-Capital Region)

- Parliament of the French Community

- Parliament of the German-speaking Community

- Parliament of Wallonia

- Parliament of the Brussels-Capital Region (within the capital's regional assembly, however, there also exist two Community Commissions, a Dutch-speaking one and a Francophone one, for various matters split up by linguistic community but under Brussels' regional competence, and even "joint community commissions" consisting of both for certain institutions that could be split up but are not.

Canada

Canada's provinces and territories:

- Parliament of Ontario

- Quebec Legislature

- General Assembly of Nova Scotia

- New Brunswick Legislature

- Manitoba Legislature

- Parliament of British Columbia

- General Assembly of Prince Edward Island

- Saskatchewan Legislature

- Alberta Legislature

- General Assembly of Newfoundland and Labrador

- Legislative Assembly of the Northwest Territories

- Yukon Legislative Assembly

- Legislative Assembly of Nunavut

Denmark

Finland

Germany

India

Indian States and Territories Legislative assemblies:

- Andhra Pradesh Legislative Assembly

- Arunachal Pradesh Legislative Assembly

- Assam Legislative Assembly

- Bihar Legislative Assembly

- Chhattisgarh Legislative Assembly

- Delhi Legislative Assembly

- Goa Legislative Assembly

- Gujarat Legislative Assembly

- Haryana Legislative Assembly

- Himachal Pradesh Legislative Assembly

- Jammu and Kashmir Legislative Assembly

- Jharkhand Legislative Assembly

- Karnataka Legislative Assembly

- Kerala Legislative Assembly

- Madhya Pradesh Legislative Assembly

- Maharashtra Legislative Assembly

- Manipur Legislative Assembly

- Meghalaya Legislative Assembly

- Mizoram Legislative Assembly

- Nagaland Legislative Assembly

- Odisha Legislative Assembly

- Puducherry Legislative Assembly

- Punjab Legislative Assembly

- Rajasthan Legislative Assembly

- Sikkim Legislative Assembly

- Tamil Nadu Legislative Assembly

- Telangana Legislative Assembly

- Tripura Legislative Assembly

- Uttar Pradesh Legislative Assembly

- Uttarakhand Legislative Assembly

- West Bengal Legislative Assembly

Indian States Legislative councils

Malaysia

Netherlands

Norway

Spain

Switzerland

United Kingdom

- Northern Ireland Assembly

- Scottish Parliament

- Welsh Parliament

Other parliaments

Contemporary supranational parliaments

- List is not exhaustive

Equivalent national legislatures

- Majlis, e.g. in Iran

- in Afghanistan: Wolesi Jirga (elected, legislative lower house) and Meshrano Jirga (mainly advisory, indirect representation); in special cases, e.g. as constituent assembly, a Loya Jirga

- in Indonesia: People's Consultative Assembly, consists of People's Representative Council (elected, legislative lower house) and Regional Representative Council (elected, legislative upper house with limited powers)

Defunct

- Parliament of Southern Ireland (1921–1922)

- People's Parliament (1940s)

- Silesian Parliament (1922–1945)

- Parliament of Northern Ireland (1921–1973)

- Batasang Pambansâ (1978–1986)

- National Assembly of the Republic of China (1913–2005)

See also

- Congress

- Delegated legislation

- Democratic mundialization

- Government

- History of democracy

- Inter-Parliamentary Union

- Legislation

- Parliamentary procedure

- Parliamentary records

- Parliament of the World's Religions

- List of current presidents of assembly

References

- Rush, Michael (2005). Parliament Today. Manchester University Press. p. 141. ISBN 9780719057953.

- Parliament Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Oxford English Dictionary, Third Edition, 2005, s.v.

- Political System Encyclopædia Britannica Online

- Jacobsen, T. (July 1943). "Primitive Democracy in Ancient Mesopotamia". Journal of Near Eastern Studies 2 (3): 159–172. doi:10.1086/370672. JSTOR 542482.

- Robinson, E. W. (1997). The First Democracies: Early Popular Government Outside Athens. Franz Steiner Verlag. ISBN 3-515-06951-8.

- Bailkey, N. (July 1967). "Early Mesopotamian Constitutional Development". American History Review 72 (4): 1211–1236. doi:10.2307/1847791. JSTOR 1847791.

- Larsen, J.A.O. (Jan. 1973). "Demokratia". Classical Philology 68 (1): 45–46. doi:10.1086/365921. JSTOR 268788.

- de Sainte, C.G.E.M. (2006). The Class Struggle in the Ancient Greek World. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-1442-3.

- Bongard-Levin, G.M. (1986). A complex study of Ancient India. South Asia Books. ISBN 81-202-0141-8.

- Sharma, J.P. (1968). Aspects of Political Ideas and Institutions in Ancient India. Motilal Banarsidass Publ.

- John Dunn:Democracy: A History, p.24

- Abbott, Frank Frost (1901). A History and Description of Roman Political Institutions. Elibron Classics. ISBN 0-543-92749-0.

- Byrd, Robert (1995). The Senate of the Roman Republic. US Government Printing Office Senate Document 103–23.

- "The Shura Principle in Islam – by Sadek Sulaiman". alhewar.com.

- The System of Islam, (Nidham ul Islam) by Taqiuddin an-Nabhani, Al-Khilafa Publications, 1423 AH – 2002 CE, p.61

- The System of Islam, by Taqiuddin an-Nabhani, p.39

- "Shura and Democracy". ijtihad.org.

- "Parthians' Achievements". Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- "مهستان". Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- HAMAZOR Publication of the World Zoroastrian Organisation: Will the issue of Dokhmenashini ever be resolved in the sub-continent?: ISSUE 3 2006. Page: 27

- HAMAZOR Publication of the World Zoroastrian Organisation: Will the issue of Dokhmenashini ever be resolved in the sub-continent?: ISSUE 3 2006. Page: 27

- Michael Burger: The Shaping of Western Civilization: From Antiquity To the Enlightenment. Page: 190

- Susana Galera: Judicial Review: A Comparative Analysis Inside the European Legal System. Page: 21

- Gaines Post: Studies in Medieval Legal Thought: Public Law And the State, 1100–1322 Page 62

- "Ayuntamiento de León – León, cradle of parliamentarism". www.aytoleon.es. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- Internet, Unidad Editorial. "La Unesco reconoce a León Como Cuna Mundial del parlamentarismo". Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- Spain (February 2012). "International Memory of the World Register [Nomination form] – The Decreta of León of 1188 – The oldest documentary manifestation of the European parliamentary system" (PDF). Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- Catedrático de la Universidad Estatal de León López González, Hermenegildo; Catedrático de la Universidad Internacional en Moscú Raytarovskiy, V.V. "The Leones parliament of 1188: The first parliament of the western world (The Magna Carta of Alfonso IX)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 21 May 2016. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Haliczer, Stephen (1981). The Comuneros of Castile: The Forging of a Revolution, 1475–1521. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press. p. 227. ISBN 0-299-08500-7.

- Liebermann, Felix, The National Assembly in the Anglo-Saxon Period (Halle, 1913; repr. New York, 1961).

- "Anglo-Saxon origins". UK Parliament.

- Kaeuper, Richard W. (1988). War Justice and Public Order: England and France in the Later Middle Ages. Oxford University Press.

- "Birth of the English Parliament: The first Parliaments". Parliament.uk. Archived from the original on 13 October 2010. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- "Was Oliver Cromwell the father of British democracy?". BBC.co.uk. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- "Hurstwic: Viking-age Laws and Legal Procedures".

- "The Faroese Parliament" (PDF).

- The High Court of Tynwald, The High Court of Tynwald (www.tynwald.org.im), retrieved 14 November 2011

- Downie Jr., Leonard (6 July 1979). "Isle of Man Marks Millennium with Pomp, Circumstance". The Washington Post. Washington DC. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- Robinson, Vaughan; McCarroll, Danny (1990), The Isle of Man: celebrating a sense of place, Liverpool University Press, p. 123, ISBN 978-0-85323-036-6

- Storia del Parlamento – Il Parlamento

- Enzo Gancitano, Mazara dopo i Musulmani fino alle Signorie – Dal Vescovado all'Inquisizione, Angelo Mazzotta Editore, 2001, p. 30.

- "10% Share of women in parliament". Our World in Data. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- "20% Share of women in parliament". Our World in Data. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- "30% Share of women in parliament". Our World in Data. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- Seidle, F. Leslie; Docherty, David C. (2003). Reforming parliamentary democracy. McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 3. ISBN 9780773525085.

- Julian Go (2007). "A Globalizing Constitutionalism? Views from the Postcolony, 1945–2000". In Arjomand, Saïd Amir (ed.). Constitutionalism and political reconstruction. Brill. pp. 92–94. ISBN 9004151745.

- "How the Westminster Parliamentary System was exported around the World". University of Cambridge. 2 December 2013. Retrieved 16 December 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Parliaments. |

- The International Association of Business and Parliament (IABP) Scottish Scheme

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- United Kingdom Parliament

_35.jpg)