Black dog (ghost)

A black dog is a motif[1] of a spectral or demonic entity found primarily in the folklore of the British Isles. The black dog is essentially a nocturnal apparition, in some cases a shapeshifter, and is often said to be associated with the Devil or described as a ghost or hellhound. Its appearance was regarded as a portent of death. It is generally supposed to be larger than a normal dog and often has large glowing eyes.[2] It is sometimes associated with electrical storms (such as Black Shuck's appearance at Bungay, Suffolk)[3] and also with crossroads, places of execution and ancient pathways.[2][4][5]

.jpg)

The origins of the black dog are difficult to discern. It is uncertain whether the creature originated in the Celtic or Germanic elements of British culture. Throughout European mythology, dogs have been associated with death. Examples of this are the Cŵn Annwn (Welsh),[6] Garmr (Norse)[7] and Cerberus (Greek),[8] all of whom were in some way guardians of the Underworld. This association seems to be due to the scavenging habits of dogs.[9] It is possible that the black dog is a survival of these beliefs.

Black dogs are generally regarded as sinister or malevolent, and a few (such as the Barghest and Shuck) are said to be directly harmful. They may also serve as familiar spirits for witches and warlocks.[10] Some black dogs, however, such as the Gurt Dog in Somerset[11] and the Black Dog of the Hanging Hills in Connecticut,[12][13] are said to behave benevolently. Some, known as guardian black dogs, guide travellers at night onto the right path or guard them from danger.[14][10]

By locale

Some of the better-known black dogs are the Barghest of Yorkshire and Black Shuck of East Anglia. Various other forms are recorded in folklore in Britain and elsewhere. Other names are Hairy Jack,[15] Padfoot,[15] Skriker,[16] Churchyard Beast,[17] Shug Monkey,[18] Capelthwaite,[19] Moddey Dhoo (or Mauthe Doog),[20] Hateful Thing,[21] Swooning Shadow,[22] Bogey Beast,[23] Gytrash (or Guytrash),[24] Oude Rode Ogen (Flanders), Tibicena (Canary Islands) and Dip (Catalonia). Although the Church Grim is not a Barghest or Shuck, it can also take the form of a large black dog.[25]

Europe

England

Black dogs have been reported from almost all the counties of England, the exceptions being Middlesex and Rutland.[26]

- On Dartmoor in southern Devon, the notorious squire Richard Cabell was said to have been a huntsman who sold his soul to the Devil. When he died in 1677, black hounds are said to have appeared around his burial chamber. The ghostly huntsman is said to ride with black dogs; this tale inspired Arthur Conan Doyle to write his well-known story The Hound of the Baskervilles.[27]

- In Lancashire, the black hound is called Barguist, Grim, Gytrash, Padfoot, Shag, Skriker or Striker, and Trash.[28][29][30]

- Stories are told of a black dog in Twyford, near Winchester.[31]

- Galley Hill in Luton, Bedfordshire, is said to have been haunted by a black dog ever since a storm set the gibbet alight sometime in the 18th century.[32]

- Betchworth Castle in Surrey is said to be haunted by a black dog that prowls the ruins at night.[33][34]

- Black Dog Hill and Black Dog Halt railway station in Wiltshire are named after a dog which is said to be found in the area.[35]

- A black dog is said to haunt Ivelet Bridge near Ivelet in Swaledale, Yorkshire. The dog is allegedly headless, and leaps over the side of the bridge and into the water, although it can be heard barking at night. It is considered a death omen, and reports claim that anybody who has seen it died within a year. The last sighting was around a hundred years ago.

- A black dog in Hertfordshire haunts the town of Stevenage near the Six Hills (a collection of Roman barrows) and Whomerley Wood.[36]

- Cannock Chase in Staffordshire has long since had rumours of a Black Dog. The Hednesford Hellhound and the Slitting Mill Bastard to name but two. Paranormal societies have investigated the phenomenon, particularly in the 1970s.[37]

Barghest

A Barghest (or Barguest) is said to roam the Snickelways and side roads of York, preying on passersby, and has also been seen near Clifford's Tower. To see the monstrous dog is said to be a warning of impending doom.

Black Dog of Aylesbury

A man who lived in a village near Aylesbury in Buckinghamshire would go each morning and night to milk his cows in a distant field. One night on his way there he encountered a sinister black dog, and every night thereafter until he brought a friend along with him. When the dog appeared again he attacked it using the yoke of his milk pails as a weapon, but when he did so the dog vanished and the man fell senseless to the ground. He was carried home alive but remained speechless and paralytic for the rest of his life.[38]

Black Dog of Lyme Regis

Near the town of Lyme Regis in Dorset stood a farmhouse that was haunted by a black dog. This dog never caused any harm, but one night the master of the house in a drunken rage tried to attack it with an iron poker. The dog fled to the attic where it leaped out through the ceiling, and when the master struck the spot where the dog vanished he discovered a hidden cache of gold and silver. The dog was never again seen indoors, but to this day it continues to haunt at midnight a lane which leads to the house called Haye Lane (or Dog Lane). Dogs who are allowed to stray in this area late at night have often mysteriously disappeared.[39][40][41] A bed and breakfast in Lyme Regis is named The Old Black Dog, and part of the legend states that the man who discovered the treasure used it to build an inn that originally stood on the site.[42]

Black Dog of Newgate

The Black Dog of Newgate has been said to haunt the Newgate Prison for over 400 years, appearing before executions. According to legend, in 1596 a scholar was sent to the prison for witchcraft, but was killed and eaten by starving prisoners before he was given a trial. The dog was said to appear soon after, and although the terrified men killed their guards and escaped, the beast is said to have hunted them down and killed them wherever they fled.[43] Grim (or Fairy Grim) is the name of a shapeshifting fairy that sometimes took the form of a black dog in the 17th-century pamphlet The Mad Pranks and Merry Jests of Robin Goodfellow. He was also referred to as the Black Dog of Newgate, but though he enjoyed frightening people he never did any serious harm.[44]

Black Dog of Northorpe

In the village of Northorpe in the West Lindsey district of Lincolnshire (not to be confused with Northorpe in the South Kesteven district) the churchyard was said to be haunted by a "Bargest". Some black dogs are said to be human beings with the power of shapeshifting. In another nearby village there lived an old man who was reputed to be a wizard. It was claimed that he would transform into a black dog and attack his neighbours' cattle. It is uncertain if there was any connection between the barghest and the wizard.[45]

Black Dog of Tring

In the parish of Tring, Hertfordshire, a chimney sweep named Thomas Colley was executed by hanging in 1751 for the drowning murder of Ruth Osborne whom he accused of being a witch. Colley's spirit now haunts the site of the gibbet in the form of a black dog, and the clanking of his chains can also be heard.[46][36] In one tale a pair of men who encountered the dog saw a burst of flame before it appeared in front of them, big as a Newfoundland with the usual burning eyes and long sharp teeth. After a few minutes it disappeared, either vanishing like a shadow or sinking into the earth.[47][48][49]

Black Shuck

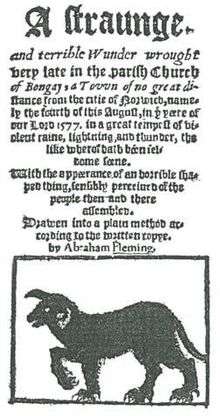

In Norfolk, Suffolk and the northern parts of Essex, a black dog known as Black Shuck (also Old Shuck or Shock) is regarded as malevolent, with stories ranging from terrifying people (or killing them outright) to being a portent of death to themselves or a person close to the victim. There are tales that in 1577 it attacked the church in the market town of Bungay, killing two people and appearing on the same day at the church in the nearby village of Blythburgh, taking the lives of another three and leaving claw marks which remain today.[50][51] In the parish of Overstrand is a dreary lane known as Shuck's Lane from its frequent appearances there. If the spot where it was just seen is examined then one may find scorch marks and the smell of brimstone.[52] There are also less common tales of a similar dog said to accompany people on their way home in the role of protector rather than an omen of misfortune.[53] Among other possible meanings, the name Shuck is derived from a provincial word meaning shaggy.[52]

Capelthwaite

In Westmorland and adjacent parts of Yorkshire there was a belief in Capelthwaite, who could take the form of any quadruped but usually appeared as a large black dog. He took his name from the barn in which he lived called Capelthwaite Barn, near Milnthorpe. He performed helpful services for the people on the farm such as rounding up the sheep, but toward outsiders he was very spiteful and mischievous until one day he was banished by a vicar.[19] As both a helper and a trickster the Capelthwaite behaved more like a domestic hobgoblin than a typical black dog.[54]

Church Grim

The Church Grim guards a local Christian church and its attached churchyard from those who would profane them including thieves, vandals, witches, and warlocks.[55] For this purpose it was the custom to bury a dog alive under the cornerstone of a church as a foundation sacrifice. Sometimes the grim will toll the bells at midnight before a death occurs. At funerals the presiding clergyman may see the dog looking out from the churchtower and determine from its "aspect" whether the soul of the departed was bound for Heaven or Hell. Another tradition states that when a new churchyard was opened the first man buried there had to guard it against the Devil. To save a human soul from such a duty a black dog was buried in the north part of the churchyard as a substitute.[56][57][58]

Gabriel Hounds

Gabriel Hounds are dogs with human heads that fly high through the air, and are often heard but seldom seen. They sometimes hover over a house, and this is taken as a sign that death or misfortune will befall those who dwell within. They are also known as Gabriel Ratchets (ratchet being a hound that hunts by scent), Gabble Retchets, and "sky yelpers", and like Yeth Hounds they are sometimes said to be the souls of unbaptised children. Popular conceptions of the Gabriel Hounds may have been partially based on migrating flocks of wild geese when they fly at night with loud honking. In other traditions their leader Gabriel is condemned to follow his hounds at night for the sin of having hunted on Sunday (much like the Cornish Dando), and their yelping cry is regarded as a death omen similar to the birds of folklore known as the Seven Whistlers.[60][61][62]

Guardian Black Dogs

Guardian Black Dogs refer to those relatively rare black dogs that are neither omens of death nor causes of it. Instead they guide lost travellers and protect them from danger. Stories of this type became more widespread starting around the early 1900s. In different versions of one popular tale a man was journeying along a lonely forest road at night when a large black dog appeared at his side and remained there until the man left the forest. On his return journey through the wood the dog reappeared and did the same as before. Years later two convicted prisoners told the chaplain that they would have robbed and murdered the wayfarer in the forest that night but were intimidated by the presence of the black dog.[14][10]

Gurt Dog

The Gurt Dog ("Great Dog") of Somerset is an example of a benevolent dog. It is said that mothers would allow their children to play unsupervised on the Quantock Hills because they believed the Gurt Dog would protect them. It would also accompany lone travellers in the area, acting as a protector and guide.[11]

Gytrash

The Gytrash (or Guytrash) is a black dog and death omen of Northern England that haunts solitary ways and also takes the form of a horse, mule and cow. It was popularised in folklore by its mention in the novel Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë.[24][63]

Hairy Jack

There are many tales of ghostly black dogs in Lincolnshire collected by Ethel Rudkin for her 1938 publication Folklore. Such a creature, known locally as Hairy Jack, is said to haunt the fields and village lanes around Hemswell, and there have been reported sightings throughout the county from Brigg to Spalding. Rudkin, who claimed to have seen Hairy Jack herself, formed the impression that black dogs in Lincolnshire were mainly of a gentle nature, and looked upon as a spiritual protector.[64] Hairy Jack was also said to haunt lonely plantations, byways, and waste places where it attacked anyone passing by.[65]

Padfoot

In Wakefield,[15] Leeds, Pudsey and some areas of Bradford the local version of the legend is known as Padfoot. A death omen like others of its type, it may become visible or invisible and exhibits certain characteristics that give it its name. It is known to follow people with a light padding sound of its paws, then appearing again in front of them or at their side. It can utter a roar unlike the voice of any known animal, and sometimes the trailing of a chain can be heard along with the pad of its feet.[66] It is best to leave the creature alone, for if a person tries to speak to or attacks it then it will have power over them. One story tells of a man who tried to kick the Padfoot and found himself dragged by it through hedge and ditch all the way to his home and left under his own window. Although usually described as black, another tale concerns a man who encountered a white Padfoot. He attempted to strike it with his stick but it passed completely through, and he ran home in fear. Soon afterward he fell sick and died.[66]

Skriker and Trash

The Skriker (or Shrieker[16]) of Lancashire and Yorkshire is a death omen like many others of its type, but it also wanders invisibly in the woods at night uttering loud, piercing shrieks. It may also take visible form as a large black dog with enormous paws that make a splashing sound when walking, like "old shoes walking in soft mud". For this reason the Skriker is also known as Trash, another word for trudge or slog.[16][67][68] The name Skriker is also derived from a dialect word for screech in reference to its frightful utterances.[69]

Yeth Hound and Wisht Hounds

The Yeth Hound (or Yell Hound) is a black dog found in Devon folklore. According to Brewer's Dictionary of Phrase and Fable, the Yeth Hound is a headless dog, said to be the spirit of an unbaptised child, that rambles through the woods at night making wailing noises. It is also mentioned in the Denham Tracts, a 19th-century collection of folklore by Michael Denham. It may have been one inspiration for the ghost dog in The Hound of the Baskervilles by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, described as "an enormous coal-black hound, but not such a hound as mortal eyes have ever seen" - with fire in his eyes and breath (Hausman 1997:47).[70]

The Wisht or Wish Hounds (wisht is a dialect word for "ghostly" or "haunted") are a related phenomenon[71] and some folklorists regard them as identical to the Yeth Hounds.[72][73] Wistman's Wood on Dartmoor in southern Devon is said to be the home of the Wisht Hounds as they make their hunting forays across the moor.[74] The road known as the Abbot's Way and the valley of the Dewerstone are favoured haunts of the hounds.[72] Their huntsman is presumably the Devil,[73] and it is said that any dog that hears the crying of the hounds will die.[72] One legend states that the ghost of Sir Francis Drake sometimes drove a black hearse coach on the road between Tavistock and Plymouth at night, drawn by headless horses and accompanied by demons and a pack of headless yelping hounds.[75] Charles Hardwick notes that black coach legends are "relatively modernised versions" of Wild Hunt and Furious Host traditions.[76] Robert Hunt further defines whish or whisht as "a common term for that weird sorrow which is associated with mysterious causes".[74]

Cornwall

- A black dog is said to have appeared to wrestlers at Whiteborough, a tumulus near Launceston.[77]

- A black dog was once said to haunt the main road between Bodmin and Launceston near Linkinhorne.[78]

- During the 1800s a Cornish mining accident resulted in numerous deaths and led to the local area being haunted by a pack of black dogs.[79]

- The parish of St Teath is haunted by a ghostly pack of dogs known as Cheney Hounds that once belonged to an old squire named Cheney. It is uncertain how he or the dogs died, but on "Cheney Downs" the dogs are sometimes seen or heard in rough weather.[80]

- The area around St Germans is haunted by a pack of hunting dogs known as Dando's Dogs. Dando was an unrepentantly sinful priest and an avid huntsman who was carried off to Hell by the Devil for his wickedness. Since then, Dando and his hounds are sometimes heard in wild chase across the countryside, especially on Sunday mornings.[81]

- The Devil's Dandy Dogs are another Cornish version of the Wild Hunt. They are often conflated with Dando's Dogs but are much more dangerous. The huntsman is the Devil himself and his dogs are not just ghosts but true hellhounds, black in colour with horns and fiery breath. One night a herdsman was journeying home across the moors and would have been overtaken by the Dandy Dogs, but when he knelt and began praying they went off in another direction in pursuit of other prey.[82][83]

Scotland

- The "Muckle Black Tyke" is a black dog that presides at the Witches' Sabbath and is supposed to be the Devil himself.[10]

- Scottish black dogs also serve as treasure guardians. Near the village of Murthly is a standing stone, and it is said that the person brave enough to move it will find a chest guarded by a black dog.[10]

Wales

- In Wales the black dog counterpart was the Gwyllgi or "Dog of Darkness", a frightful apparition of a mastiff with baleful breath and blazing red eyes. Also related are the spectral Cŵn Annwn, connected with the otherworld realm of Annwn referred to in the Four Branches of the Mabinogi and elsewhere. However, they are described as being dazzling white rather than black in the medieval text.[6][84][85]

- Another ghostly black dog is said to haunt St Donat's Castle, with some witnesses claiming it to have been accompanied by a hag.

Channel Islands and Isle of Man

- In the Isle of Man is the legend of the Moddey Dhoo, 'black dog' in Manx, also styled phonetically Mauthe Doog or Mawtha Doo. It is said to haunt the environs of Peel Castle.[20] People believe that anyone who sees the dog will die soon after the encounter with the dog. It is mentioned by Sir Walter Scott in The Lay of the Last Minstrel:

- For he was speechless, ghastly, wan

- Like him of whom the Story ran

- Who spoke the spectre hound in Man.

- Also from the Isle of Man is a tale of a guardian black dog that prevented the deaths of several men. A fishing boat was waiting in Peel Harbour for its skipper to command the crew on a night's fishing. They waited all night but the skipper never came. In the early morning a sudden storm sprang up in which the boat might have been lost. When the skipper rejoined his crew he told them that his way had been blocked by a great black dog, and whichever way he turned it always stood before him until he finally turned back.[86]

- In the Channel Island of Guernsey, there are two named dogs. One, Tchico (Tchi-coh two Norman words for dog, whence cur), is headless, and is supposed to be the phantom of a past Bailiff of Guernsey, Gaultier de la Salle, who was hanged for falsely accusing one of his vassals. The other dog is known as Bodu or tchen Bodu (tchen being dog in Dgèrnésiais). His appearance, usually in the Clos du Valle, foretells death of the viewer or someone close to him. There are also numerous other unnamed apparitions, usually associated with placenames derived from bête (beast).[87]

- In Jersey folklore, the Black Dog of Death is also called the Tchico, but a related belief in the Tchian d'Bouôlé (Black Dog of Bouley) tells of a phantom dog whose appearance presages storms.[88] The real reason for the superstition of the Black Dog of Bouley Bay is thought to be due to smugglers. If the superstition was fed and became 'real' to the locals, then the bay at night would be deserted and the smuggling could continue in security. The pier at Bouley Bay made this an exceptionally easy task. A local pub retains the name the "Black Dog".[89]

- On mainland Normandy the Rongeur d'Os wanders the streets of Bayeux on winter nights as a phantom dog, gnawing on bones and dragging chains along with it.[90]

Mainland Europe

Oude Rode Ogen ("Old Red Eyes") or the "Beast of Flanders" was a spirit reported in Flanders, Belgium in the 18th century who would take the form of a large black dog with fiery red eyes. In Wallonia, the southern region of Belgium, folktales mentioned the Tchén al tchinne ("Chained Hound" in Walloon), a hellish dog bound with a long chain, that was thought to roam in the fields at night.[91] In Germany and the Czech lands it was said that the devil would appear in the form of a large black dog.[92][93]

The earliest known report of a black dog was in France in AD 856, when one was said to materialise in a church even though the doors were shut. The church grew dark as it padded up and down the aisle, as if looking for someone. The dog then vanished as suddenly as it had appeared.[94]

In Lower Brittany there are stories of a ghost ship crewed by the souls of criminals with hellhounds set to guard them and inflict on them a thousand tortures.[95]

the Americas

Latin America

Black dogs with fiery eyes are reported throughout Latin America from Mexico to Argentina under a variety of names including the Perro Negro (Spanish for black dog), Nahual (Mexico), Huay Chivo and Huay Pek (Mexico) - alternatively spelled Uay/Way/Waay Chivo/Pek, Cadejo (Central America), the dog Familiar (Argentina) and the Lobizon (Paraguay and Argentina). They are usually said to be either incarnations of the Devil or a shape-changing sorcerer.[96]

United States

The legend of a small black dog has persisted in Meriden, Connecticut since the 19th century. The dog is said to haunt the Hanging Hills: a series of rock ridges and gorges that serve as a popular recreation area. The first non-local account came from W. H. C. Pychon in The Connecticut Quarterly, in which it is described as a death omen. It is said that, "If you meet the Black Dog once, it shall be for joy; if twice, it shall be for sorrow; and the third time shall bring death."[12]

A New England black dog story comes from southeastern Massachusetts in the area known, by some, as the Bridgewater Triangle. In the mid-1970s, the town of Abington was, reportedly, terrorized by a large, black dog that caused a panic. A local fireman saw it attacking ponies. Local police unsuccessfully searched for it, at first but, eventually, a police officer sighted the dog walking along train tracks and shot at it. Apparently, the bullets had no effect on the animal and it wandered off, never to be seen again.

Asia

India

The Mahākanha Jātaka of the Buddhist Pali Canon includes a story about a black dog named Mahākanha (Pali; lit. "Great black"). Led by the god Śakra in the guise of a forester, Mahākanha scares unrighteous people toward righteousness so that fewer people will be reborn in hell.

His appearance portends the moral degeneration of the human world, when monks and nuns do not behave as they should and humanity has gone astray from ethical livelihood.[97]

Arabia

Jinn, although not necessarily evil, but often thought of as malevolent entities, are thought to use black dogs as their mounts. The negative depiction of dogs probably derives from their close association with "eating the dead" (relieshing bones) and digging out graves. The jinn likewise are often said to roam around graveyards and eating corpses. These characteristics relates them to each other.[98]

Other colours

England

- The Gallytrot (or Galleytrot) of Northern England and Suffolk is a large white dog with a shadowy or indeterminate outline, and will chase anyone who runs away from it. The word is derived from gally, to frighten.[57][99]

Scotland

- The Cù Sìth of the Scottish Highlands is dark green in colour and the size of a stirk (a yearling calf). They were usually kept tied up in the brugh (fairy mound) as watchdogs, but sometimes they accompanied the women during their expeditions or were allowed to roam about alone, making their lairs among the rocks. They moved silently, had large paws the size of adult human hands, and had a loud baying that could be heard far out at sea. It is said that anyone who heard them bark three times was overcome with terror and died of fright.[100]

In popular culture

The legend has been referenced many times in popular culture. One of the most famous ghostly black dogs in fiction appears in Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's The Hound of the Baskervilles, where a large dog-like creature haunts a family estate. Sherlock Holmes is brought in to determine if the dog is in fact real or supernatural. This story makes use of folktales where black dogs symbolize death.

Another famous ghostly black dog may be found in J.K. Rowling's Harry Potter series: the "Grim", a "giant, spectral dog that haunts churchyards"[103] is "the worst omen of death"[103] according to Harry Potter's divination teacher, Professor Trelawney. Another reference to the legend can be found in the same book, Harry Potter & the Prisoner of Azkaban, Padfoot being the nickname of Sirius Black, an animagus who can turn into a large black dog and mistaken as the Grim by Harry.

See also

References

- https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1003&context=gljuh

- Simpson & Roud 2000, 2003, p.25.

- Westwood & Simpson 2005, pp.687–88.

- Stone, Alby Infernal Watchdogs, Soul Hunters and Corpse Eaters in Trubshaw 2005, pp.36–37.

- McEwan 1986, p.147.

- Stone, Alby Infernal Watchdogs, Soul Hunters and Corpse Eaters in Trubshaw 2005, p.53.

- Stone, Alby Infernal Watchdogs, Soul Hunters and Corpse Eaters in Trubshaw 2005, pp.44–45.

- Stone, Alby Infernal Watchdogs, Soul Hunters and Corpse Eaters in Trubshaw 2005, p.38.

- Stone, Alby Infernal Watchdogs, Soul Hunters and Corpse Eaters in Trubshaw 2005, pp.54–55.

- Briggs 1977, pp. 135–40.

- Rickard & Michell 2000, pp. 286–7.

- "''The Connecticut Quarterly''". Books.google.com. 2008-05-19. Retrieved 2019-02-18.

- Offut, Jason (2019). Chasing American Monsters. Woodbury, Minnesota: Llewellyn Books. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-7387-5995-1.

- Briggs 1976, pp. 207–8.

- Bord & Bord 1980, 1981, p.78.

- Bowker 1887, pp. 27–36.

- Guiley 2008, p. 67.

- Redfern 2004, pp. 36, 52, 182-4.

- Henderson 1879, pp. 275–6.

- Evans-Wentz 1966, 1990, p. 129.

- Wilson and Lupton 2013, p. 38.

- Guiley 2007, 2000, p. 61 (variant of "Black Shuck").

- Steiger 2011, p. 45.

- Wright 1923 p. 770.

- Briggs 1976, p. 74–5.

- Trubshaw 2005, p. 2.

- Barber & Barber 1988, 1990, p.3.

- Fields 1998, p. 37.

- Simpson & Roud 2000, 2003, p. 366.

- Crosby 2000, pp. 14, 19, 26, 165.

- Feldwick 2006, 2007, pp. 89–90

- Matthews 2004, p. 35–36.

- Janaway 2005, p.10.

- Stewart 1990, pp. 49–50.

- "Black Dog Hill" Real British Ghosts.

- Gerish 1911 p. 11.

- [http://ukwildman.blogspot.com/2015/11/englands-black-dog-legends.html

- Hartland 1906, pp. 235–6.

- Hartland 1906, pp. 238–41.

- Udal 1922, pp. 167–8.

- Briggs 1977, pp. 138–40.

- The Old Black Dog "The Black Dog Legend"

- Clark 2007, pp. 86–87.

- Collier 1841, p. 43.

- Gutch and Peacock 1908, p. 54.

- Hertfordshire's Last Witch Hunt Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine Ch. 3.

- Thiselton-Dyer 1893, pp. 106–8.

- Hartland 1906, p. 237.

- Briggs 1977, p. 137.

- "1577, August 4: Suffolk Black Dog" Anomalies.

- Rickard & Michell 2000, p. 287.

- Hartland 1906, pp. 237–8.

- "The Tollesbury Midwife" Shuckland.

- Briggs 1976, p. 223 ("Hobgoblin").

- Simpson, Jacqueline (1994). Penguin Book of Scandinavian Folktales. 15. Penguin Books. ISBN 9780140175806.

- Henderson 1879, p. 274.

- Wright 1913, p. 194.

- Briggs 1976, pp. 74–5.

- Rose, Carol (2001). Giants, Monsters, and Dragons. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-32211-4.

- Hardwick 1872, pp. 153–4.

- Henderson 1879, pp. 129–32.

- Wright 1913, p. 195–7.

- Wood, Juliette. "The Gytrash"

- Codd, Daniel. Haunted Lincolnshire. Tempus Publishing Ltd (2006) pp. 75–78. ISBN 0-7524-3817-4

- Gutch and Peacock 1908, p. 53.

- Henderson 1879, pp. 273–4.

- Wright 1913, pp. 194–5.

- Harland and Wilkinson 1867, pp. 91–2.

- Hartland 1906, p. 238.

- Brewer. Hausemen & Hausemen 1997.

- "The Dark Huntsman". Legendarydartmoor.co.uk. 2007-10-28. Retrieved 2012-06-18.

- Hunt 1865, p. 150.

- Briggs 1976, p. 440.

- Hunt 1865, Introduction p. xix.

- Hunt 1865, p. 260.

- Hardwick 1872, p. 192.

- Deane & Shaw 2003, p. 82.

- Deane & Shaw 2003, p. 44; also Semmens, Jason. '"Whyler Pystry": A Breviate of the Life and Folklore-Collecting Practices of William Henry Paynter (1901–1976) of Callington, Cornwall." Folklore 116, No. 1 (2005) pp. 75–94.

- Thiselton-Dyer 1893, p. 108.

- Hunt 1865, p. 151.

- Hunt 1865, pp. 247–51.

- Hunt 1865, pp. 251–2.

- Hartland 1906, p. 244.

- Gantz 1976, pp. 46–47.

- Pugh 1990, pp. 19, 67

- Briggs 1976, p. 301.

- de Garis, Marie (1986) Folklore of Guernsey, The Guernsey Press, ASIN B0000EE6P8

- Bord & Bord 1980, 1981, p. 95.

- Jersey Maritime Museum for references to the folklore of the Black Dog

- Wright 1846, p. 128.

- Warsage, Rodolphe de Sorcellerie et Cultes Populaires en Wallonie, Noir Dessein, 1998.

- Varner, Gary R. Creatures in the mist: little people, wild men and spirit beings around the world : a study in comparative mythology in Algora Publishing 2007, pp. 114–15.

- Stejskal, Martin (1991). Labyrintem tajemna, aneb Průvodce po magických místech Československa (1st ed.). Prague: Paseka. p. 36. ISBN 80-85192-08-X.

- McNab, Chris "Mythical Monsters: The scariest creatures from legends, books, and movies" in Scholastic Publishing 2006, pp. 8-9.

- Thiselton-Dyer 1893, p. 289.

- Burchell 2007, pp. 1, 24.

- Rouse, W. H. D. (1901). "The Jataka Volume IV". Internet Sacred Text Archive. Pali Text Society. Retrieved 2019-09-27.

- Amira El Zein: The Evolution of the Concept of Jinn from Pre-Islam to Islam'. p. 264

- Briggs 1976, p. 183.

- Campbell 1900, pp. 30–32.

- Gill 1932 Ch. 6 Sec. 2.

- Morrison 1911, p. 29.

- Rowling, J.K. Harry Potter & the Prisoner of Azkaban. Bloomsburry.

Bibliography

- Barber, Sally and Barber, Chips (1988, 1990). Dark and Dastardly Dartmoor. Obelisk Publications. ISBN 0-946651-26-4.

- Bord, Colin and Bord, Janet (1980, 1981). Alien Animals. Book Club Associates.

- Bowker, James (1887). Goblin Tales of Lancashire. London: W. Swan Sonnenschein & Co.

- Brewer, E. Cobham. Brewer's Dictionary of Phrase and Fable (first pub. 1870).

- Briggs, Katharine (1976). An Encyclopedia of Fairies. Pantheon Books. ISBN 0394409183.

- Briggs, Katharine (1977). British Folk Tales and Legends. Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN 0415286026.

- Burchell, Simon (2007). Phantom Black Dogs in Latin America Heart of Albion Press. ISBN 978-1-905646-01-2.

- Campbell, John Gregorson (1900). Superstitions of the Highlands and Islands of Scotland. Glasgow: James MacLehose and Sons.

- Clark, James (2007). Haunted London. Tempus Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7524-4459-8.

- Collier, John Payne (ed.) (1841). The Mad Pranks and Merry Jests of Robin Goodfellow (reprinted from anon. 1628 ed.) London: Percy Society.

- Crosby, Alan (2000). The Lancashire Dictionary of Dialect, Tradition and Folklore. Smith Settle. ISBN 1-85825-122-2.

- Crossley-Holland, Kevin (1980). The Norse Myths. Andre Deutsch. ISBN 0-233-97271-4.

- Deane, Tony and Shaw, Tony (2003). Folklore of Cornwall. Tempus Publishing. ISBN 0-7524-2929-9.

- Evans-Wentz, Walter (1966, 1990) [1911]. The Fairy Faith in Celtic Countries. Citadel Press. ISBN 0-8065-1160-5.

- Feldwick, Matthew (2006, 2007). Haunted Winchester. Tempus Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7524-3846-7.

- Fields, Kenneth (1998). Lancashire Magic & Mystery. Sigma Leisure. ISBN 1-85058-606-3.

- Gantz, Jeffrey (trans) (1976). The Mabinogion. Penguin Classics. ISBN 0-14-044322-3.

- de Garis, Marie (1986). Folklore of Guernsey. The Guernsey Press. ASIN B0000EE6P8.

- Gerish, William Blyth (1911). The Folk-Lore of Hertfordshire. Bishop's Stortford.

- Gill, W. Walter (1932). A Second Manx Scrapbook. Arrowsmith.

- Guiley, Rosemary Ellen (2000, 2007) [1992]. The Encyclopedia of Ghosts and Spirits (3rd ed.). Facts on File. ISBN 0816067376.

- Guiley, Rosemary Ellen (2008). Ghosts and Haunted Places. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 0791093921.

- Gutch, Eliza and Peacock, Mabel (1908). County Folklore (Vol. 5). David Nutt.

- Hardwick, Charles (1872). Traditions, Superstitions and Folklore. Manchester: A. Ireland & Co.

- Harland, John and Wilkinson, T. T. (1867). Lancashire Folklore. London: Frederick Warne and Co.

- Hartland, Edwin Sidney (1906). English Fairy and Other Folk Tales. Walter Scott Publishing Co.

- Hausman, Gerald and Hausman, Loretta (1997). The Mythology of Dogs: Canine Legend St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-18139-6.

- Henderson, William (1879). Folklore of the Northern Counties of England and the Borders (2nd ed.) W. Satchell, Peyton & Co.

- Hunt, Robert (1865). Popular Romances of the West of England (Vol. 1). London: John Camden Hotten.

- Janaway, John (2005). Haunted Places of Surrey. Countryside Books. ISBN 1-85306-932-9.

- Matthews, Rupert (2004). Haunted Places of Bedfordshire & Buckinghamshire. Countryside Books. ISBN 1-85306-886-1.

- McEwan, Graham J. (1986). Mystery Animals of Britain and Ireland. Robert Hale Ltd. ISBN 0709028016.

- Michell, John F. and Rickard, Robert J. M. (1977). Phenomena: A Book of Wonders. Thames Hudson Ltd. ISBN 0-500-01182-6 (hardback). ISBN 0-500-27094-5 (paperback).

- Morrison, Sophia (1911). Manx Fairy Tales. London: David Nutt.

- Paynter, William and Semmens, Jason (2008). The Cornish Witch-finder: William Henry Paynter and the Witchery, Ghosts, Charms and Folklore of Cornwall. Federation of Old Cornwall Societies. ISBN 978-0-902660-39-7.

- Pugh, Jane (1990). Welsh Ghostly Encounters. Gwasg Carreg Gwalch. ISBN 0-86381-152-3.

- Readers Digest (1977). Folklore, Myths and Legends of Britain. Readers Digest Association. p. 45.

- Redfern, Nick (2004). Three Men Seeking Monsters. Pocket Books. ISBN 0743482549.

- Rickard, Bob and Michell, John (2000). The Rough Guide to Unexplained Phenomena. Rough Guides Ltd. ISBN 1858285895

- Ritson, Joseph (1831). Fairy Tales, Now First Collected: To which are prefixed two dissertations: 1. On Pygmies. 2. On Fairies. Elibron Classics [facsimile], 2007. ISBN 1-4021-4753-8. See pp. 137–9 ("The Mauthe Doog").

- Simpson, Jacqueline and Roud, Steve (2000, 2003). Oxford Dictionary of English Folklore. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-860766-0.

- Steiger, Brad (2011). Real Monsters, Gruesome Critters, and Beasts from the Darkside. Visible Ink Press. ISBN 9781578592203.

- Stewart, Frances D. (1990). Surrey Ghosts Old and New. AMCD. ISBN 0-9515066-8-4.

- Thiselton-Dyer, T. F. (1893). The Ghost World. London: Ward & Downey.

- Trubshaw, Robert Nigel (ed.) (2005). Explore Phantom Black Dogs. Heart of Albion Press. ISBN 1-872883-78-8.

- Udal, John Symonds (1922). Dorsetshire Folklore. S. Austin & Sons.

- Waldron, David and Reeve, Chris (2010). Shock! The Black Dog of Bungay: A Case Study in Local Folklore. Hidden Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9555237-7-9.

- Westwood, Jennifer and Simpson, Jacqueline (2005). The Lore of the Land: A Guide to England's Legends, from Spring-heeled Jack to the Witches of Warboys. Penguin. ISBN 0-14-100711-7.

- Wright, Elizabeth Mary (1913). Rustic Speech and Folk-Lore. Humphrey Milford, Oxford University Press.

- Wright, Joseph (1923). The English Dialect Dictionary (Vol. 2). Humphrey Milford, Oxford University Press.

- Wright, Thomas (1846). Literature, Popular Superstitions, and History of England in the Middle Ages (Vol. 1). London: John Russell Smith.

Further reading

- Burchell, Simon (2008) Phantom Black Dogs in Prehispanic Mexico PDF, Heart of Albion.

- Sherwood, Simon J. (2010) Apparitons of Black Dogs in Smith, Matthew D. (ed.) Anomalous Experiences: Essays from Parapsychological and Psychological Perspectives, McFarland, ISBN 978-0-7864-4398-7

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Black dog (legend). |

- Black Dog Legends and Reports in Chronological Order

- Mysterious Britain article on the Black Dog

- Story from North Longford in Ireland

- Monstrous.com article on the Black Dog, including theories as to its origin

- The Black Dog of the Hanging Hills at Haunted Connecticut

- Shuckland, an exhaustive database of the Black Dogs of East Anglia

- A multi-witness, indoor, child-centred black dog case from France, Charles Fort Institute

- Sahih Muslim Book 004, Hadith Number 1032. - Hadith Collection

- Sahih Muslim Book 010, Hadith Number 3813

- Abu Dawud Book 010, Hadith Number 2840.