Pan-Celticism

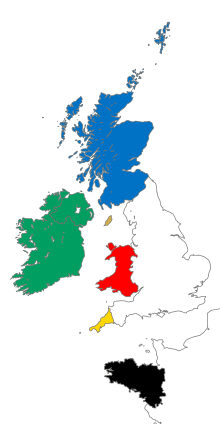

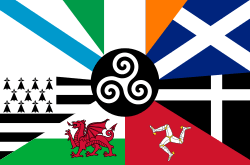

Pan-Celticism (Irish: Pan-Chelteachas), also known as Celticism or Celtic nationalism is a political, social and cultural movement advocating solidarity and cooperation between Celtic nations (both the Gaelic and Brythonic branches) and the modern Celts in North-Western Europe.[1] Some pan-Celtic organisations advocate the Celtic nations seceding from the United Kingdom and France and forming their own separate federal state together, while others simply advocate very close cooperation between independent sovereign Celtic nations, in the form of Irish nationalism, Scottish nationalism, Welsh nationalism, Breton nationalism, Cornish nationalism and Manx nationalism.

As with other pan-nationalist movements such as pan-Slavism, pan-Germanism, pan-Turanianism, pan-Iranism, pan-Latinism and others, the pan-Celtic movement grew out of Romantic nationalism and specific to itself, the Celtic Revival. The pan-Celtic movement was most prominent during the 19th and 20th centuries (roughly 1838 until 1939). Some early pan-Celtic contacts took place through the Gorsedd and the Eisteddfod, while the annual Celtic Congress was initiated in 1900. Since that time the Celtic League has become the prominent face of political pan-Celticism. Initiatives largely focused on cultural Celtic cooperation, rather than explicitly politics, such as music, arts and literature festivals, are usually referred to instead as inter-Celtic.

Terminology

There is some controversy surrounding the term Celts. One such example was the Celtic League's Galician crisis.[1] This was a debate over whether the Spanish region of Galicia should be admitted. The application was rejected on the basis of a lack of a presence of a Celtic language.[1]

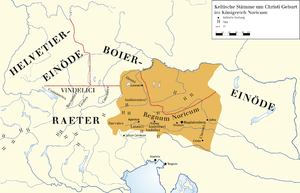

Some Austrians claim that they have a Celtic heritage that became Romanized under Roman rule and later Germanized after Germanic invasions.[2] Austria is the location of the first characteristically Celtic culture to exist.[2] After the annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany in 1938, in October 1940 a writer from the Irish Press interviewed Austrian physicist Erwin Schrödinger who spoke of Celtic heritage of Austrians, saying "I believe there is a deeper connection between us Austrians and the Celts. Names of places in the Austrian Alps are said to be of Celtic origin."[3] Contemporary Austrians express pride in having Celtic heritage and Austria possesses one of the largest collections of Celtic artefacts in Europe.[4]

Organisations such as the Celtic Congress and the Celtic League use the definition that a 'Celtic nation' is a nation with recent history of a traditional Celtic language.[1]

History

Modern conception of the Celtic peoples

Before the Roman Empire and the rise of Christianity, people lived in Iron Age Britain and Ireland, speaking languages from which the modern Gaelic languages (including Irish, Scottish Gaelic and Manx) and Brythonic languages (including Welsh, Breton and Cornish) descend. These people, along with others in Continental Europe who once spoke now extinct languages from the same Indo-European branch (such as the Gauls, Celtiberians and Galatians), have been retroactively referred to in a collective sense as the Celts, particularly in a wide spread manner since the turn of the 18th century. Variations of the term "Celt", such as Keltoi had been used in antiquity by the Greeks and the Romans to refer to some groups of these people, such as Herodotus' use of it in regards to the Gauls.

The modern usage of "Celt" in reference to these cultures grew up gradually. A pioneer in the field was George Buchanan, a 16th-century Scottish scholar, Renaissance humanist and tutor to king James IV of Scotland. From a Scottish Gaelic-speaking family, Buchanan in his Rerum Scoticarum Historia (1582), went over the writings of Tacitus who had discussed the similarity between the language of the Gauls and the ancient Britons. Buchanan concluded, if the Gauls were Celtae, as they were described as in Roman sources, then the Britons were Celtae too. He began to see a pattern in place names and concluded that the Britons and Irish Gaels once spoke one Celtic language which later diverged. It wouldn't be until over a century later when these ideas were widely popularised; first by the Breton scholar Paul-Yves Pezron in his Antiquité de la Nation et de la langue celtes autrement appelez Gaulois (1703) and then by the Welsh scholar Edward Lhuyd in his Archaeologia Britannica: An Account of the Languages, Histories and Customs of the Original Inhabitants of Great Britain (1707).

By the time the modern concept of the Celts as a people had emerged, their fortunes had declined substantially, taken over by Germanic people. Firstly, the Celtic Britons of sub-Roman Britain were swamped by a tide of Anglo-Saxon settlement from the 5th century on and lost most of their territory to them. They were subsequently referred to as the Welsh people and the Cornish people. A group of these fled Britain altogether and settled in Continental Europe in Armorica, becoming the Breton people. The Gaels for a while actually expanded, pushing out of Ireland to conquer Pictland in Britain, establishing Alba by the 9th century. From the 11th century onward, the arrival of the Normans, caused problems not only for the English but also for the Celts. The Normans invaded the Welsh kingdoms (establishing the Principality of Wales), the Irish kingdoms (establishing the Lordship of Ireland) and took control of the Scottish monarchy through intermarrying. This advance was often done in conjunction with the Catholic Church's Gregorian Reform, which was centralising the religion in Europe.

The dawning of early modern Europe effected the Celtic peoples in ways which saw what small amount of independence they had left firmly subordinated to the emerging British Empire and in the case of the Duchy of Brittany, the Kingdom of France. Although both the Kings of England (the Tudors) and the Kings of Scotland (the Stewarts) of the day claimed Celtic ancestry and used this in Arthurian cultural motifs to lay the basis for a British monarchy ("British" being suggested by Elizabethan John Dee), both dynasties promoted a centralising policy of Anglicisation. The Gaels of Ireland lost their last kingdoms to the Kingdom of Ireland after the Flight of the Earls in 1607, while the Statutes of Iona attempted to de-Gaelicise the Highland Scots in 1609. The effects of these initiates were mixed, but took from the Gaels their natural leadership element, which had patronised their culture.

Under Anglocentric British rule, the Celtic-speaking peoples were reduced to a marginalised, largely poor people, small farmers and fishermen, clinging to the coast of the North Atlantic. Following the Industrial Revolution in the 18th century, greater multitudes were Anglicised and fled into a diaspora around the British Empire as an industrial proletariat. Further de-Gaelicisation took place for the Irish during the Great Hunger and the Highland Scots during the Highland Clearances. Similarly for the Bretons, after the French Revolution, the Jacobins demanded greater centralisation, against regional identities and for Francization, enacted by the French Directory in 1794. However, Napoleon Bonaparte was greatly attracted to the romantic image of the Celt, which was partly based on Jean-Jacques Rousseau's glorification of the noble savage and the popularity of James Macpherson's Ossianic tales throughout Europe. Bonaparte's nephew, Napoleon III, would later have the Vercingétorix monument erected to honour the Celtic Gaulish leader.[5] Indeed, in France the phrase "nos ancêtres les Gaulois" (our ancestors the Gauls) was invoked by Romantic nationalists,[5] typically in a republican fashion, to refer to the majority of the people, contrary to the aristocracy (claimed to be of Frankish-Germanic descent).

Dawning of Pan-Celticism as a political idea

Following the dying down of Jacobitism as a political threat in Britain and Ireland, with the firm establishment of Hanoverian Britain under the liberal, rationalist philosophy of the Enlightenment, a backlash of Romanticism in the late 18th century occurred and "the Celt" was rehabilitated in literature, in a movement which is sometimes known as "Celtomania." The most prominent native representatives of the initial stages of this Celtic Revival were James Macpherson, author of the Poems of Ossian (1761) and Iolo Morganwg, founder of the Gorsedd. The imagery of the "Celtic World" also inspired English and Lowland Scots poets such as Blake, Wordsworth, Byron, Shelley and Scott. In particular the Druids inspired fascination for outsiders, as English and French antiquarians, such as William Stukeley, John Aubrey, Théophile Corret de la Tour d'Auvergne and Jacques Cambry, began to associate ancient megaliths and dolmens with the Druids.[nb 1]

In the 1820s, early pan-Celtic contacts began to develop, firstly between the Welsh and the Bretons, as Thomas Price and Jean-François Le Gonidec worked together to translate the New Testament into Breton.[6] The two men were champions of their respective languages and both highly influential in their own countries. It was in this spirit that a Pan-Celtic Congress took place at the Cymreigyddion y Fenni's annual Eisteddfod in Abergavenny in 1838, where Bretons attended. Among these participants was Théodore Hersart de La Villemarqué, author of the Macpherson-Morganwg influenced Barzaz Breiz, who imported the Gorsedd idea into Brittany. Indeed, the Breton nationalists would be the most enthusiastic pan-Celticists,[6] acting as a lynch-pin between the different parts; "trapped" within another state (France), this allowed them to draw strength from kindred peoples across the Channel and they also shared a strong attachment to the Catholic faith with the Irish.

Across Europe, modern Celtic Studies were developing as an academic discipline. The Germans led the way in the field with Indo-European linguist Franz Bopp in 1838, followed up by Johann Kaspar Zeuss' Grammatica Celtica (1853). Indeed, as German power was growing in rivalry with France and England, the Celtic Question was of interest to them and they were able to perceive the shift towards Celtic-based nationalisms. Heinrich Zimmer, the Professor of Celtic at Friedrich Wilhelm University in Berlin (predecessor of Kuno Meyer), spoke in 1899 of the powerful agitation in the "Celtic fringe of the United Kingdom's rich overcoat" and predicted that pan-Celticism would become a political force as important to the future of European politics as the much more established movements of pan-Germanism and pan-Slavism.[7] Other academic treatments included Ernest Renan's La Poésie des races celtiques (1854) and Matthew Arnold's The Study of Celtic Literature (1867). The attention given by Arnold was a double-edged sword; he lauded Celtic poetic and musical achievements, but effeminised them and suggested they needed the cement of a sober, orderly Anglo-Saxon rule.

A concept arose among some European philologists, particularly articulated by Karl Wilhelm Friedrich Schlegel, whereby the "care of the national language is a sacred trust",[8] or put more simply, "no language, no nation." This dictum was also adopted by nationalists in Celtic nations, particularly Thomas Davis of the Young Ireland movement, who, contrary to the earlier Catholic-based "civic rights" activism of a Daniel O'Connell, asserted an Irish nationalism where the Irish language would become hegemonic once again. As he claimed a "people without a language of its own is only half a nation."[8] In a less explicitly political context, language revivalist groups emerged such as the Society for the Preservation of the Irish Language, which would later become the Gaelic League. In a Pan-Celtic context, Charles de Gaulle (uncle of the more famous General Charles de Gaulle), who involved himself in Breton autonomism and advocated for a Celtic Union in 1864, argued that "so long as a conquered people speaks another language than their conquers, the best part of them remains free." De Gaulle corresponded with people in Brittany, Ireland, Scotland and Wales, arguing that each needed to cooperate in a spirit of Celtic unity and above all defend their native languages or otherwise their position as Celtic nations would be extinct. A Pan-Celtic review was founded by de Gaulle's comrade Henri Gaidoz in 1873, known as Revue Celtique.

In 1867 de Gaulle organised the first ever Pan-Celtic gathering in Saint-Brieuc, Brittany. No Irish attended and the guests were mainly Welsh and Breton.[9]

T. E. Ellis, the leader of Cymru Fydd was a proponent of Pan-Celticism, stating "We must work for bringing together Celtic reformers and Celtic peoples. The interests of Irishmen, Welshmen and [Scottish] Crofters are almost identical. Their past history is very similar, their present oppressors are the same and their immediate wants are the same.[10]

Pan-Celtic Congress and the Celtic Association era

.png)

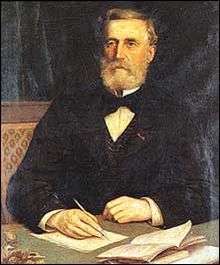

The first major Pan-Celtic Congress was organised by Edmund Edward Fournier d'Albe and Bernard FitzPatrick, 2nd Baron Castletown, under the auspices of their Celtic Association and was held in August 1901 in Dublin. This had followed on from an earlier sentiment of pan-Celtic feeling at the National Eisteddfod of Wales, held in Liverpool in 1900. Another influence was Fournier's attendance at Feis Ceoil in the late 1890s, which drew musicians from the different Celtic nations. The two leaders formed somewhat of an idiosyncratic pair; Fournier, of French parentage embraced an ardent Hibernophilia and learned the Irish language, while FitzPatrick descended from ancient Irish royalty (the Mac Giolla Phádraig of Osraige), but was serving in the British Army and had earlier been a Conservative MP (indeed, the original Pan-Celtic Congress was delayed for a year because of the Second Boer War).[11] The main intellectual organ of the Celtic Association was Celtia: A Pan-Celtic Monthly Magazine, edited by Fournier, which ran from January 1901 until 1904 and was briefly revived in 1907 before finally ending for good in May 1908. Its inception was welcomed by Breton François Jaffrennou.[12] An unrelated publication "The Celtic Review" was founded in 1904 and ran until 1908.[12]

Historian Justin Dolan Stover of Idaho State University describes the movement as having "uneven successes".[12]

In total, the Celtic Association was able to organise three Pan-Celtic Congresses: Dublin (1901), Caernarfon (1904) and Edinburgh (1907). Each of these opened with an elaborate neo-druidic ceremony, with the laying of the Lia Cineil ("Race Stone"), which drew inspiration from the Lia Fáil and Stone of Scone. The stone was five foot high and consisted of five granite blocks, each with a letter of the respective Celtic nation etched into it in their own language (i.e. - "E" for Ireland, "A" for Scotland, "C" for Wales).[nb 2] At the laying of the stone, the Archdruid of the Eisteddfod, Hwfa Môn would say three times in Gaelic, while holding a partly unsheathed sword, "Is there peace?" to which the people responded "Peace."[13] The symbolism inherent in this was meant to represent a counterpoise to the British Empire's assimilating Anglo-Saxonism as articulated by the likes of Rudyard Kipling.[14] For the pan-Celts, they imagined a restored "Celtic race", but where each Celtic people would have its own national space without assimilating all into a uniformity. The Lia Cineil was also intended as a phallic symbol, referencing the ancient megaliths historically associated with the Celts and overturning the "feminisation of the Celts by their Saxon neighbours."[14]

The response of the most advanced and militant nationalism of a "Celtic" people; Irish nationalism; was mixed. The pan-Celts were lampooned by D. P. Moran in The Leader, under the title of "Pan-Celtic Farce."[13] The folk costumes and druidic aesthetics were especially mocked, meanwhile Moran, who associated Irish nationality with Catholicism, was suspicious of the Protestantism of both Fournier and FitzPatrick.[13] The participation of the latter as a "Tommy Atkins" against the Boers (whom Irish nationalists supported with the Irish Transvaal Brigade) was also highlighted as unsound.[13] Moran concluded that pan-Celticism was "parasitic" from Irish nationalism, created by a "foreigner" (Fournier) and sought to misdirect Irish energies.[13] Others were less polemical; opinion in the Gaelic League was divided and though they elected not to send an official representative, some members did attend Congress meetings (including Douglas Hyde, Patrick Pearse and Michael Davitt).[15] More enthusiastic was Lady Gregory, who imagined an Ireland-led "Pan-Celtic Empire", while William Butler Yeats also attended the Dublin meeting.[15] Prominent Gaelic League activists such as Pearse, Edward Martyn, John St. Clair Boyd, Thomas William Rolleston, Thomas O'Neill Russell, Maxwell Henry Close and William Gibson all made financial contributions to the Pan-Celtic Congress.[16] Ruaraidh Erskine was an attendant. Erskine himself was an advocate of a "Gaelic confederation" between Ireland and Scotland.[17]

David Lloyd George later to go on to be the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom delivered a speech at the 1904 Celtic Congress.[18]

Breton Regionalist Union founder Régis de l'Estourbeillon attended the 1907 congress, headed the Breton faction of the procession and placed the Breton stone on the Lia Cineill. Henry Jenner, Arthur William Moore and John Crichton-Stuart, 4th Marquess of Bute likewise attended the 1907 congress.[19]

Erskine made an effort to set up a "union of Welsh, Scots and Irish with a view to action on behalf of Celtic communism". He wrote to Thomas Gwynn Jones asking for suggestions on Welshmen to invite to London for a meeting on setting such a thing up. It is unknown if such a meeting ever took place.[20]

In Paris, 1912 the "La Ligue Celtique Francaise" was launched and had a magazine called "La Poetique" which published news and literature from all around the Celtic world.[12]

Pan-Celticism after the Easter Rising

Celtic nationalisms were boosted immensely by the Irish Easter Rising of 1916, where a group of revolutionaries belonging to the Irish Republican Brotherhood struck militantly against the British Empire during the First World War to assert an Irish Republic. Part of their political vision, building on earlier Irish-Ireland policies was a re-Gaelicisation of Ireland: that is to say a de-colonisation of Anglo cultural, linguistic and economic hegemony and a re-assertion of the native Celtic culture. After the initial rising, their politics coalesced in Ireland around Sinn Féin. In other Celtic nations, groups were founded holding similar views and voiced solidarity with Ireland during the Irish War of Independence: this included the Breton-journal Breiz Atao, the Scots National League of Ruaraidh Erskine and various figures in Wales who would later go on to found Plaid Cymru. The presence of James Connolly and the October Revolution in Russia taking place at the same time, also led some to imagine a Celtic socialism or communism; an idea associated with Erskine, as well as the revolutionary John Maclean and William Gillies. Erskine claimed the "collectivist ethos in the Celtic past", had been, "undermined by Anglo-Saxon values of greed and selfishness."

The hope of some Celtic nationalists that a semi-independent Ireland could act as a springboard for Irish Republican Army-esque equivalents for their own nations and the "liberation" of the rest of the Celtosphere would prove a disappointment. A militant Scottish volunteer force founded by Gillies, Fianna na hAlba; which like the Óglaigh na hÉireann advocated republicanism and Gaelic nationalism; was discouraged by Michael Collins who advised Gillies that the British state was stronger in Scotland than Ireland and that public opinion was more against them. Once the Irish Free State was established, the ruling parties; Fine Gael or Fianna Fáil; were content to engage in inter-governmental diplomacy with the British state in an effort to have returned the counties in Northern Ireland, rather than supporting Celtic nationalist militants within Britain. The Irish state, particularly under Éamon de Valera did make some effort on the cultural and linguistic front in regards to Pan-Celticism. For instance in the summer of 1947, the Irish Taoiseach de Valera visited the Isle of Man and met with Manxman, Ned Maddrell. While there he had the Irish Folklore Commission make recordings of the last, old, native Manx Gaelic-speakers, including Maddrell.

Post-war initiatives and the Celtic League

A group called "Aontacht na gCeilteach" (Celtic Unity) was set up to promote the pan-Celtic vision in November 1942. It was headed by Éamonn Mac Murchadha. MI5 believed it to be a secret front for the Irish fascist party Ailtiri na hAiseirghe and was to serve as "a rallying point for Irish, Scottish, Welsh and Breton nationalists". The group had the same postal address as the party. At its foundation the group stated that "the present system is utterly repugnant to the celtic conception of life" and called for a new order based upon a "distinctive celtic philosophy". Ailtiri na hAiseirghe itself had a pan-Celtic vision and had established contacts with pro-Welsh independence political party Plaid Cymru and Scottish independence activist Wendy Wood. One day the party covered South Dublin city with posters saying "Rhyddid i Gymru" (Freedom for Wales)[21][22][23][24] Rhisiart Tal-e-bot, former President of the European Free Alliance Youth is a member.[25][22][26]

The rejuvenation of Irish republicanism during the post-war period and into The Troubles had some inspiration not only for other Celtic nationalists, but militant nationalists from other "small nations", such as the Basques with the ETA. Indeed, this was particularly pertinent to the secessionist nationalisms of Spain, as the era of Francoist Spain was coming to a close. As well as this, there was renewed interest in all things Celtic in the 1960s and 1970s. In a less militant fashion, elements within Galician nationalism and Asturian nationalism began to court Pan-Celticism, attending the Festival Interceltique de Lorient and the Pan Celtic Festival at Killarney, as well as joining the International Section of the Celtic League.[27] Although this region had once been under Iberian Celts, had a strong resonance in Gaelic mythology (i.e. - Breogán) and even during the Early Middle Ages had a small enclave of Celtic Briton emigrants at Britonia (similar to the case with Brittany), no Celtic language had been spoken there since the 8th century and today they speak Romance languages.[28] During the so-called "Galician crisis" of 1986,[27] the Galicians were admitted to the Celtic League as a Celtic nation (Paul Mosson had argued for their inclusion in Carn since 1980).[27] This was subsequently overturned the following year, as the Celtic League reaffirmed the Celtic languages as the integral and defining factor in what is a Celtic nation.[29]

Following the Brexit referendum there were calls for Pan-Celtic Unity. In November 2016, the First Minister of Scotland, Nicola Sturgeon stated the idea of a "Celtic Corridor" of the island of Ireland and Scotland appealed to her.[30] In January 2019 the leader of the Welsh nationalist Plaid Cymru party, Adam Price spoke in favour of cooperation among the Celtic nations of Britain and Ireland following Brexit. Among his proposals were a Celtic Development Bank for joint infrastructure and investment projects in energy, transport and communications in Ireland, Wales, Scotland, and the Isle of Man, and the foundation of a Celtic union, the structure of which is already existent in the Good Friday Agreement according to Price. Speaking to RTE, the Irish national broadcaster he proposed Wales and Ireland working together to promote the indigenous languages of each nation.[31]

Anti-Celticism

A movement among some, primarily English, archeologists known as "Celtoscepticism" emerged from the late 1980s, through the 1990s.[32] This school of thought, initiated by John Collis sought to undermine the basis of Celticism and cast doubts on the legitimacy of the very concept or any usage of the term "Celts". This strain of thought was particularly hostile to all but archaeological evidence.[33] Partly a reaction to the rise in Celtic devolutionist tendencies, these scholars were opposed to describing the Iron Age people of Britain as Celtic Britons and even disliked the use of the phrase Celtic in describing the Celtic language family. Collis, an Englishman from the University of Cambridge, was hostile to the methodology of German professor Gustaf Kossinna and was hostile to Celts as an ethnic identity coalescing around a concept of hereditary ancestry, culture and language (claiming this was "racist"). Aside from this Collis was hostile to the use of Classical literature and Irish literature as a source for the Iron Age period, as exemplified by Celtic scholars such as Barry Cunliffe. Throughout the duration of the debate on the historicity of the ancient Celts, John T. Koch stated that it is "the scientific fact of a Celtic family of languages that has weathered unscathed the Celtosceptic controversy."[34]

Collis was not the only figure in this field. The two other figures most prominent in the field were Malcolm Chapman with his The Celts: The Construction of a Myth (1992) and Simon James of the University of Leicester with his The Atlantic Celts: Ancient People or Modern Invention? (1999).[35] In particular, James engaged in a particularly heated exchange with Vincent Megaw (and his wife Ruth) on the pages of Antiquity.[36] The Megaws (along with others such as Peter Berresford Ellis)[37] suspected a politically motivated agenda; driven by English nationalist resentment and anxiety at British Imperial decline; in the whole premise of Celtosceptic theorists (such as Chapman, Nick Merriman and J. D. Hill) and that the anti-Celtic position was a reaction to the formation of a Scottish Parliament and Welsh Assembly. For his part, James stepped forward to defend his fellow Celtosceptics, claiming that their rejection of the Celtic idea was politically motivated, but invoked "multiculturalism" and sought to deconstruct the past and imagine it as more "diverse", rather than a Celtic uniformity.[36]

Attempts to identify a distinct Celtic Race were made by the "Harvard Archaeological Mission to Ireland" in the 1930s, led by Earnest Hooton, which drew the conclusions needed by its sponsor-government. The findings were vague and did not stand up to scrutiny, and were not pursued after 1945.[38][39] The genetic studies by David Reich suggest that the Celtic areas had three major population changes, and that the last group in the Iron Age, who spoke Celtic languages, had arrived in about 1000 BCE, after the building of iconic supposedly-Celtic monuments like Stonehenge and Newgrange.[40] Reich confirmed that the Indo-European root of the Celtic languages reflected a population shift, and was not just a linguistic adoption.

Manifestations

Pan-Celticism can operate on one or all of the following levels listed below:

Linguistics

Linguistic organisations promote linguistic ties, notably the Gorsedd in Wales, Cornwall and Brittany, and the Irish government-sponsored Columba Initiative between Ireland and Scotland. Often, there is a split here between the Irish, Scots and Manx, who use Q-Celtic Goidelic languages, and the Welsh, Cornish and Bretons, who speak P-Celtic Brythonic languages.

Music

For Liberty's cause against alien laws

When Lochiel and O'Neill and Llewellyn drew steel

For Alba and Erin and Cambria's weal

The flower of the free, the heather, the heather

The Bretons and Scots and Irish together

The Manx and the Welsh and Cornish forever

Six nations are we all Celtic and free!

Music is a notable aspect of Celtic cultural links. Inter-Celtic festivals have been gaining popularity, and some of the most notable include those at Lorient, Killarney, Kilkenny, Letterkenny and Celtic Connections in Glasgow.[41][42]

Sports

Sporting contact is much less common, although Ireland and Scotland play each other at hurling/shinty internationals.[43] There is also the Pro14 involving rugby union teams from Ireland, Wales and Scotland.[44]

Political

Political groups such as the Celtic League, along with Plaid Cymru and the Scottish National Party have co-operated at some levels in the Parliament of the United Kingdom, and Plaid Cymru has asked questions in Parliament about Cornwall and cooperates with Mebyon Kernow. The Regional Council of Brittany, the governing body of the Region of Brittany, has developed formal cultural links with the Welsh Senedd and there are fact-finding missions. Political pan-Celticism can be taken to include everything from a full federation of independent Celtic states, to occasional political visits. During the Troubles, the Provisional IRA adopted a policy of not mounting attacks in Scotland and Wales, as they viewed England (having been the nation which initially invaded Ireland) alone as the colonial force occupying Ireland. This was also possibly influenced by the IRA chief of staff Seán Mac Stíofáin (John Stephenson), a London-born republican who identified as a "Pan-Celt".[45]

Town twinnings

Town twinning is common between Wales – Brittany and Ireland – Brittany, covering hundreds of communities, with exchanges of local politicians, choirs, dancers and school groups.[46]

Historical connections

That hung around many a rebel throat

Resistance and rising through the years

We've lost good men, shed blood and tears

Its time for England a truth to face

They will never defeat the Celtic race

Scots and Irish we are one

Our people, our culture, our Gaelic tongue

—Maire McNally, We're Celts.

The kingdom of Dál Riata was a Gaelic overkingdom on the western seaboard of Scotland with some territory on the northern coasts of Ireland. In the late 6th and early 7th century it encompassed roughly what is now Argyll and Bute and Lochaber in Scotland and also County Antrim in Northern Ireland.[47]

As recently as the 13th century, "members of the Scottish elite were still proud to proclaim their Gaelic-Irish origins and identified Ireland as the homeland of the Scots."[48] The 14th century Scottish King Robert the Bruce asserted a common identity for Ireland and Scotland.[48] However, in later medieval times, Irish and Scottish interests diverged for a number of reasons, and the two peoples grew estranged.[49] The conversion of the Scots to Protestantism was one factor.[49] The stronger political position of Scotland in relation to England was another.[49] The disparate economic fortunes of the two was a third reason; by the 1840s Scotland was one of the richest areas in the world and Ireland one of the poorest.[49]

Over the centuries there was considerable migration between Ireland and Scotland, primarily as Scots Protestants took part in the plantation of Ulster in the 17th century and then later, as many Irish began to be evicted from their homes, some emigrating to Scottish cities in the 19th century to escape the "Irish famine". Recently the field of Irish-Scottish studies has developed considerably, with the Irish-Scottish Academic Initiative (ISAI) founded in 1995. To date, three international conferences have been held in Ireland and Scotland, in 1997, 2000 and 2002.[50]

Organisations

- The International Celtic Congress is a non-political cultural organisation that promotes the Celtic language in the six nations of Ireland, Scotland, Brittany, Ireland, Isle of Man and Cornwall.

- The Celtic League, is a Pan-Celtic political organization.

Celtic regions/countries

A number of Europeans from the central and western regions of the continent have some Celtic ancestry. As such it is generally claimed that the 'litmus test' of Celticism is a surviving Celtic language [1] and it was on this criterion that the Celtic league rejected Galicia. The following regions have a surviving Celtic language and it on this criterion that they are considered, by The Pan Celtic Congress in 1904 and Celtic League, to be the Celtic nations.[1][51]

Other regions with Celtic heritage are:

- Austria[2] - Within the famous Hallstatt cultural region - possible home of the Celts.

- Czechia - Home of the Boii (Boiohaemum - Bohemia)

- England[52]

- Faroe Islands

- France - Known previously, in classical times, as Gallia/Gaul. Classical writings on Gaul and its native Celtic tribes are the most extensive literature we have from the time.

- Iceland

- Italy - A large portion of the Northern Italy known as Cisalpine Gaul was inhabited by Celtic tribes.

- Portugal - Home to the Lusitani, Gallaecian, Turdetani and other Celtic tribes.

- Spain - A large portion of the Iberian peninsula was inhabited by Celtic tribes. Spain and Portugal has been hypothesized as the place of origin of the Celts by Professor John Koch, of the University of Wales.[53]

- Asturias[1][54] - the principality of Asturias was named after the Astur Celtic tribe.

- Cantabria - The current autonomous community (former duchy) was named after the Cantabri tribe.

- Galicia[1] (with North Portugal[54]) – together as Gallaecia

- Castile and León

- Castile-La Mancha

- Extremadura

- Community of Madrid

- Andalusia (Turdetani and other tribes)

- Slovenia Historical part of Celtic Kingdom of Noricum

Celts outside Europe

Areas with a Celtic language speaking population

There are notable Irish and Scottish Gaelic speaking enclaves in Atlantic Canada.[55]

The Patagonia region of Argentina has a sizeable Welsh speaking population. The Welsh settlement in Argentina started in 1865 and is known as Y Wladfa.

The Celtic diaspora

The Celtic diaspora in the Americas, as well as New Zealand and Australia, is significant and organised enough that there are numerous organisations, cultural festivals and university-level language classes available in major cities throughout these regions.[56] In the United States, Celtic Family Magazine is a nationally distributed publication providing news, art, and history on Celtic people and their descendants.[57]

The Irish Gaelic games of Gaelic football and hurling are played across the world and are organised by the Gaelic Athletic Association while the Scottish game shinty has seen recent growth in the United States[58]

Timeline of Pan-Celticism

J.T. Koch observes that modern Pan-Celticism arose in the contest of European romantic pan-nationalism, and like other pan-nationist movements, flourished mainly before the First World War.[59] He sees twentieth century efforts in this regard as possibly arising out of a post-modern search for identity in the face of increased industrialization, urbanization and technology.

- 1820: The Royal Celtic Society founded in Scotland[60]

- 1838: First Celtic Congress called Pan-Celtic Congress, Abergavenny[61]

- 1867: Second Celtic Congress, Saint-Brieuc[62]

- 1888: Pan-Celtic Society formed in Dublin[63]

- 1891:Pan-Celtic Society disbands[63]

- 1919–1922: Irish War of Independence, five-sixths of Ireland becomes independent, Northern Ireland gets devolved government

- 1939–1945: Second World War and German occupation of Brittany

- 1947: Celtic Union formed[64]

- 1950: Collapse of Celtic Union[64]

- 1950: Cornwall hosts its first Celtic congress[65]

- 1961: Modern Celtic League founded at Rhosllanerchrugog[66]

- 1971: Killarney Pan Celtic Festival begins[67]

- 1997: Columba Initiative begins[68]

- 1999: Scottish Parliament[69] and Welsh Assembly[70] open

- 2000: The Cornish Constitutional Convention is formed[71]

- 2000–2001:The Cornish Constitutional Convention collect over 50,000 signatures endorsing the call for a Cornish Assembly.[71]

See also

- Armes Prydein

- Alan Heusaff

- John Stuart Stuart-Glennie

- Ruaraidh Erskine

- Richard Jenkin

- Agnes O'Farrelly

- Sophia Morrison

- Théodore Hersart de la Villemarqué

- Charles de Gaulle

- Mona Douglas

Notes

- The current of neo-Druidism, deriving from the writings of the likes of William Stukeley and Iolo Morganwag, had its origins more in the milieu of freemasonry than any lineal connection to the ancient Celtic Druids and their culture, which survived latest in the Gaelic world with the filí and seanchaí (existing alongside Christianity). Thus neo-paganism had a very limited appeal to most people in Celtic nations, instead being largely English and Welsh based. English-based quasi-masonic groups such as the Ancient Order of Druids provided the inspiration for Iolo's Gorsedd. Later masonic groups and writers such as Godfrey Higgins and then Robert Wentworth Little's Ancient and Archaeological Order of Druids, were English founded or based.

- Due to the all-but-extinction of the Cornish language, the movement of Cornish nationalism would not be included within the Pan-Celtic Congress until 1904, after Henry Jenner and L. C. R. Duncombe-Jewell of the Cornish Celtic Society made their argument to the Celtic Association. Cornwall ("K") was subsequently added to the Lia Cineil and the Cornish have been recognised as the sixth Celtic nation ever since.

References

- Ellis, Peter Berresford (2002). Celtic dawn: the dream of Celtic unity. ISBN 9780862436438. Retrieved 19 January 2010.

- Carl Waldman, Catherine Mason. Encyclopedia of European Peoples. Infobase Publishing, 2006. P. 42.

- Walter J. Moore. Schrödinger: Life and Thought. Cambridge, England, UK: Press Syndicate of Cambridge University Press, 1989. p.373.

- Kevin Duffy. Who Were the Celts? Barnes & Noble Publishing, 1996. P. 20.

- Fenn 2001, p. 65.

- Haywood 2014, p. 190.

- O'Donnell 2008, p. 134.

- Motherway 2016, p. 87.

- De Barra (2018), page 108

- De Barra (2018), page 78

- Platt 2011, p. 61.

- Stover, Justin Dolan (2012). "Modern Celtic Nationalism in the Period of the Great War: Establishing Transnational Connections". Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium. 32: 286–301. JSTOR 23630944.

- Platt 2011, p. 62.

- Platt 2011, p. 64.

- Platt 2011, p. 63.

- Barra, Caoimhín De (30 March 2018). The Coming of the Celts, AD 1862: Celtic Nationalism in Ireland and Wales. ISBN 9780268103408.

- "Connections across the North Channel: Ruaraidh Erskine and Irish Influence in Scottish Discontent, 1906-1920". 17 April 2013.

- "Celts divided by more than the Irish Sea".

- "Meriden Morning Record - Google News Archive Search".

- Barra, Caoimhín De (30 March 2018). The Coming of the Celts, AD 1862: Celtic Nationalism in Ireland and Wales. ISBN 9780268103408.

- Architects of Resurrection: Ailtiri na hAiserighe and the fascist 'new order' in Ireland by R. M. Douglas (pg 271)

- Pittock, Murray (1999). Celtic Identity and the British Image. ISBN 9780719058264.

- "Resurgence". 1966.

- Williams, Derek R. (1 July 2014). Following 'An Gof': Leonard Truran, Cornish Activist and Publisher. ISBN 9781908878113.

- "Celtic League: General Secretary in Udb Interview".

- Robert William White (2006). Ruairí Ó Brádaigh: The Life and Politics of an Irish Revolutionary. ISBN 978-0253347084.

- Berresford Ellis 2002, p. 27.

- Berresford Ellis 2002, p. 26.

- Berresford Ellis 2002, p. 28.

- "Scottish first minister backs calls for 'Celtic corridor'".

- Nualláin, Irene Ní (10 January 2019). "Welsh party leader calls for Celtic political union". RTÉ.ie.

- "How being Celtic got a bad name – and why you should care". The Conversation. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- "Celtoscepticism, a convenient excuse for ignoring non-archaeological evidence?". Raimund Karl. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- "Another lost cause? Pan-Celticism, race and language". Irish Studies Review. doi:10.1080/09670880802658174.

- "The Rise and Fall of the 'C' word (Celts)". Heritage Daily. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- "The academic debate on the meaning of 'Celticness'". University of Leicester. Archived from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- "Historical notes: Did the ancient Celts really exist?". The Independent. 5 January 1999. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- Carew M. The Quest for the Irish Celt - The Harvard Archaeological Mission to Ireland, 1932-1936. Irish Academic Press, 2018

- Irish Independent article "Skulls, a Nazi director and the quest for the 'true' Celt", 29 April 2018

- Reich D. Who we are and how we got here; Oxford UP 2018, pp.114-121.

- "ALTERNATIVE MUSIC PRESS-Celtic music for a "New World Paradigm"". Retrieved 2 January 2010.

- "Scottish Music Festivals-Great Gatherings of Artists". Archived from the original on 25 February 2010. Retrieved 2 January 2010.

- BBC report

- "Y Gynghrair Geltaidd". BBC Chwaraeon (in Welsh). British Broadcasting Corporation. 28 September 2005. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- Pittock, Murray. Celtic Identity and the British Image. Manchester University Press, 1999. p. 111

- "Home page of Cardiff Council – Cardiff's twin cities". Cardiff Council. 15 June 2010. Retrieved 10 August 2010.

- Oxford Companion to Scottish History p. 161 162, edited by Michael Lynch, Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-923482-0.

- "Making the Caledonian Connection: The Development of Irish and Scottish Studies." by T.M. Devine. Research Institute of Irish and Scottish Studies, University of Aberdeen. in Radharc: A Journal of Irish Studies Vol 3: 2002 pg 4. The article in turn cites "Myth and Identity in Early Medieval Scotland" by E.J. Cowan, Scottish Historical Review, xxii (1984) pgs 111–135.

- "Making the Caledonian Connection: The Development of Irish and Scottish Studies." by T.M. Devine. Research Institute of Irish and Scottish Studies, University of Aberdeen. in Radharc: A Journal of Irish Studies Vol 3: 2002 pgs 4–8

- Devine, T.M. "Making the Caledonian Connection: The Development of Irish and Scottish Studies." Radharc Journal of Irish Studies. New York. Vol 3, 2002.

- Celtic League Homepage

- "We're nearly all Celts under the skin", "The Scotsman", 21 September 2006.

- Koch, John. Tartessian, Europe’s newest and oldest Celtic language, http://www.historyireland.com/pre-history-archaeology/tartessian-europes-newest-and-oldest-celtic-language/

- "National Geographic map of celtic regions". Retrieved 20 January 2010.

- O Broin, Brian. "An Analysis of the Irish-Speaking Communities of North America: Who are they, what are their opinions, and what are their needs?". Retrieved 31 March 2012. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Modern Irish Linguistics". University of Sydney. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- "The Welsh in America". Wales Arts Review. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- "Thursday's Scottish gossip". BBC News. 20 August 2009. Retrieved 20 January 2010.

- Koch, John T., Celtic Culture, ABC-CLIO, 2006 ISBN 9781851094400

- "The Royal Celtic Society". Archived from the original on 2 March 2016. Retrieved 5 February 2010.

- "Celtic Congresses in other countries". Retrieved 5 February 2010.

- "The International Celtic Congress Resolutions and Themes". Retrieved 5 February 2010.

- Hughes, J. B. (1953). "The Pan-Celtic Society". The Irish Monthly. 81 (953): 15–38. JSTOR 20516479.

- "The Capital Scot". Archived from the original on 8 January 2011. Retrieved 5 February 2010.

- "A short history of the Celtic Congress". Archived from the original on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 5 February 2010.

- "Rhosllanerchrugog". Archived from the original on 1 January 2011. Retrieved 5 February 2010.

- "Welcome to the 2010 Pan Celtic Festival". Retrieved 5 February 2010.

- "Columba Initiative". 16 December 1997. Retrieved 5 February 2010.

- "Scottish Parliament". Retrieved 5 February 2010.

- "Queen and Welsh Assembly". Retrieved 5 February 2010.

- "Campaign for a Cornish assembly". Retrieved 5 February 2010.

Bibliography

- Bailyn, Bernard (2012). Strangers Within the Realm: Cultural Margins of the First British Empire. UNC Press Books. ISBN 978-0807839416.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Berresford Ellis, Peter (1985). The Celtic Revolution: Study in Anti-Imperialism. Y Lolfa Cyf. ISBN 978-0862430962.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Berresford Ellis, Peter (2002). Celtic Dawn: The Dream of Celtic Unity. Y Lolfa Cyf. ISBN 978-0862436438.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Carruthers, Gerard (2003). English Romanticism and the Celtic World. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1139435949.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Collins, Kevin (2008). Catholic Churchmen and the Celtic Revival in Ireland, 1848-1916. Four Courts Press. ISBN 978-1851826582.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fenn, Richard K (2001). Beyond Idols: The Shape of a Secular Society. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198032854.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hechter, Michael (1975). Internal Colonialism: The Celtic Fringe in British National Development, 1536-1966. Routledge. ISBN 978-0710079886.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dudley Edwards, Owen (1968). Celtic Nationalism. Routledge. ISBN 978-0710062536.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gaskill, Howard (2008). The Reception of Ossian in Europe. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1847146007.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Haywood, John (2014). The Celts: Bronze Age to New Age. Routledge. ISBN 978-1317870166.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jensen, Lotte (2016). The Roots of Nationalism: National Identity Formation in Early Modern Europe, 1600-1815. Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 978-9048530649.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Motherway, Susan (2016). The Globalization of Irish Traditional Song Performance. Routledge. ISBN 978-1317030041.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- O'Donnell, Ruán (2008). The Impact of the 1916 Rising: Among the Nations. Irish Academic Press. ISBN 978-0716529651.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- O'Driscoll, Robert (1985). The Celtic Consciousness. George Braziller. ISBN 978-0807611364.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- O'Rahilly, Cecile (1924). Ireland and Wales: Their Historical and Literary Relations. Longman's.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ortenberg, Veronica (2006). In Search of the Holy Grail: The Quest for the Middle Ages. A&B Black. ISBN 978-1852853839.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pittock, Murray G. H. (1999). Celtic Identity and the British Image. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0719058264.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pittock, Murray G. H. (2001). Scottish Nationality. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1137257246.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Platt, Len (2011). Modernism and Race. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1139500258.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tanner, Marcus (2006). The Last of the Celts. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300115352.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Loffler, Marion (2000). A Book of Mad Celts: John Wickens and the Celtic Congress of Caernaroon 1904. Gomer Press. ISBN 978-1859028964.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)