Irredentism

Irredentism describes various political and popular movements that claim, reclaim (usually on behalf of the corresponding purported nation), and seek to occupy territory that the movement's members consider to be a "lost" (or "unredeemed") territory, based on history or even legend.[1][2] (The breadth of this definition’s scope—sometimes despite unclarities of the historical bounds of the putative nations or peoples—is subject to terminological disputes about any underlying claims of expansionism.)

Etymology

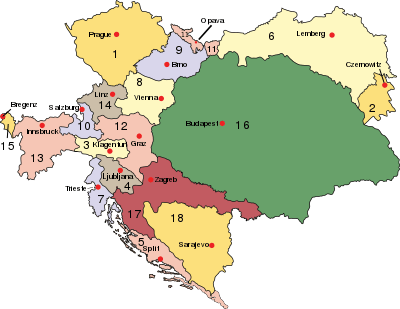

The word (from Italian irredento for "unredeemed") was coined in Italy from the phrase Italia irredenta ("unredeemed Italy").[3] This originally referred to rule by Austria-Hungary over territories mostly or partly inhabited by ethnic Italians, such as Trentino, Trieste, Gorizia, Istria, Fiume and Dalmatia during the 19th and early 20th centuries.[4] An area liable to be targetted by a claim is sometimes called an "irredenta".[5]

A common way to express a claim to adjacent territories on the grounds of historical or ethnic association is by using the adjective "Greater" as a prefix to the country name. This conveys the image of national territory at its maximum conceivable extent with the country "proper" at its core. The use of "Greater" does not always convey an irredentistic meaning.

Current government level irredentist claims

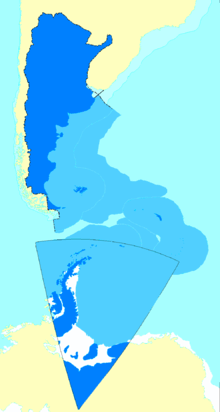

Argentina

Argentina has claimed land that used to be part of, or was associated with, the Spanish territory of the Viceroyalty of the Rio de la Plata. The viceroyalty began to dissolve into separate independent states in the early 19th century, one of which later became Argentina.[6] The claims included, amongst other areas, parts of what in 2019 were Chile, Paraguay, Brazil, Uruguay and Bolivia. Some of these claims have been settled although others are still active. The active claims include part of the land border with Chile, a section of the Antarctic continent, and the British South Atlantic islands, including the Falklands.[7]

Argentina renews these claims periodically.[8] It considers the Falkland archipelago to be part of the Tierra del Fuego Province, along with South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands. Its claim is included in the transitional provisions of the Constitution of Argentina as amended in 1994:[9][10]

The Argentine Nation ratifies its legitimate and non-prescribing sovereignty over the Malvinas, Georgias del Sur and Sandwich del Sur Islands and over the corresponding maritime and insular zones, as they are an integral part of the National territory. The recovery of these territories and the full exercise of sovereignty, respecting the way of life for its inhabitants and according to the principles of international law, constitute a permanent and unwavering goal of the Argentine people.

Bengal

United Bengal is a political ideology of a Unified Bengali-speaking Nation in South Asia. The ideology was developed by Bengali Nationalists after the First Partition of Bengal in 1905. The British-ruled Bengal Presidency was divided into Western Bengal and Eastern Bengal and Assam to weaken the Independence Movement; after much protest, Bengal was reunited in 1911.

The second attempt by the British to partition Bengal along communal lines was in 1947. The United Bengal proposal was the bid made by Prime Minister of Bengal Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy and Sarat Chandra Bose to found a united and independent nation-state of Bengal.[11][12] The proposal was floated as an alternative to the partition of Bengal on communal lines. The initiative failed due to British diplomacy and communal conflict between Bengali Muslims and Bengali Hindus that eventually led to the Second Partition of Bengal.

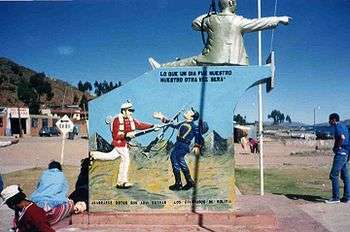

Bolivia

The 2009 constitution of Bolivia states that the country has an "unrenounceable right over the territory that gives it access to the Pacific Ocean and its maritime space".[13] This is understood as territory that Bolivia and Peru ceded to Chile after the War of the Pacific, which left Bolivia as a landlocked country.

China

The preamble to the Constitution of the People's Republic of China states, "Taiwan is part of the sacred territory of the People's Republic of China (PRC). It is the lofty duty of the entire Chinese people, including our compatriots in Taiwan, to accomplish the great task of reunifying the motherland." The PRC claim to sovereignty over Taiwan is generally based on the theory of the succession of states, with the PRC claiming that it is the successor state to the Republic of China.[14]

However, the Communist Party of China has never controlled Taiwan.[15] The Government of the Republic of China formerly administered both mainland China and Taiwan but has been administering primarily Taiwan only since the Chinese Civil War in which it fought the armed forces of the Communist Party of China. While the official name of the state remains 'Republic of China', the country is commonly called 'Taiwan', as Taiwan makes up 99% of the controlled territory of the ROC.

In fact, the ruling Qing Dynasty of China ceded Taiwan and the Pescadores to Japan in perpetuity in the Treaty of Shimonoseki in 1895, along with the Liaodong Peninsula.[16] The Republic of Formosa or Democratic State of Taiwan was a short-lived republic[17][18] that then existed on the island of Taiwan for about five months in 1895 in the period between the formal cession of Taiwan to the Empire of Japan and 'de facto' Japanese occupation and control. Japan then established a colony on Taiwan that existed until control of Taiwan was ceded to the Nationalist Government of the Republic of China in 1945.[19]

Article 4 of the Constitution of the Republic of China originally stated that "[t]he territory of the Republic of China within its existing national boundaries shall not be altered except by a resolution of the National Assembly"[20] Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, the Government of the Republic of China on Taiwan maintained itself to be the legitimate ruler of Mainland China as well. As part of its current policy of continuing the 'status quo', the ROC has not renounced claims over the territories currently controlled by the People's Republic of China, Mongolia, Russia, Myanmar and some Central Asian states. However, Taiwan does not actively pursue these claims in practice; the remaining claims that Taiwan is actively seeking are of uninhabited islands: the Senkaku Islands, whose sovereignty is also asserted by Japan and the PRC. As far as the Paracel Islands and Spratly Islands in the East Sea [called by Vietnam] or South China Sea [called by China] are concerned, Vietnam has repeatedly claimed its sovereignty over these islands, rejecting China's so-called “Nine Dash Line” claim.

Comoros

Article 1 of the Constitution of the Union of the Comoros begins: "The Union of the Comoros is a republic, composed of the autonomous islands of Mohéli, Mayotte, Anjouan, and Grande Comore." Mayotte, geographically a part of the Comoro Islands, was the only island of the four to vote against independence from France (independence losing 37%–63%) in the referendum held December 22, 1974. Mayotte is currently a department of the French Republic.[21][22]

Guatemala

Guatemala has claimed Belize in whole or in part since 1821.

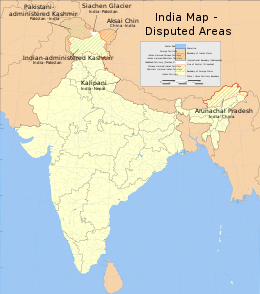

India

All of the European colonies on the Indian subcontinent that were not part of the British Raj have been annexed by India since it gained its independence from the British Empire. The 1961 Indian annexation of Goa is an example. The Indian integration of Junagadh is an example of an annexation of a territory that was part of the British Raj but that was not incorporated into India at the time of its independence.

Akhand Bharat, literally Undivided India or Whole India, is an irredentist call to reunite Pakistan and Bangladesh (and for some, Sri Lanka, the Maldives, Nepal and Bhutan) with India to form an Undivided India as it existed before partition in 1947 during the British Raj (and before that, during other periods of political unity in South Asia when most of the Indian Subcontinent was under the rule of one power, such as during the Maurya Empire, the Gupta Empire, the Mughal Empire or the Maratha Empire). The call for Akhanda Bharata has often been raised by mainstream Indian nationalistic cultural and political organizations such as the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).[23][24][25] Other major Indian political parties such as the Indian National Congress, while maintaining positions against the partition of India on religious grounds, do not necessarily subscribe to a call to reunite South Asia in the form of Akhanda Bharata.

The region of Kashmir in north India has been the issue of a territorial dispute between India and Pakistan since 1947, the Kashmir conflict. Multiple wars have been fought over the issue, the first one immediately upon independence and partition in 1947 itself. To stave off a Pakistani and tribal invasion, Maharaja Hari Singh of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir signed the Instrument of Accession with India. Kashmir has remained divided in three parts, administered by India, Pakistan and China, since then. On the basis of the instrument of accession, however, India continues to claim the entire Kashmir region as its integral part. All modern Indian political parties support the return of the entirety of Kashmir to India, and all official maps of India show the entire Kashmir (including parts under Pakistani or Chinese administration after 1947) as an integral part of India.

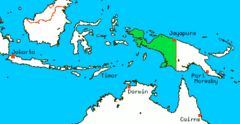

Indonesia

Indonesia claimed all territories of the former Dutch East Indies, and previously viewed British plans to group the British Malaya and Borneo into a new independent federation of Malaysia as a threat to its objective to create a united state called Greater Indonesia. The Indonesian opposition of Malaysian formation has led to the Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation in the early 1960s. It also held Portuguese Timor (modern East Timor) from 1975 to 2002 based on irredentist claims.

The idea of uniting former British and Dutch colonial possessions in Southeast Asia actually has its roots in the early 20th century, as the concept of Greater Malay (Melayu Raya) was coined in British Malaya espoused by students and graduates of Sultan Idris Training College for Malay Teachers in the late 1920s.[26] Some political figures in Indonesia including Mohammad Yamin and Sukarno revived the idea in the 1950s and named the political union concept as Greater Indonesia.

Israel and Palestine

The nation state of Israel was established in 1948. The United Nations General Assembly passed U.N. Resolution 181, otherwise known as the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine, with 72% of the valid votes. Eventually, Israeli independence was achieved following the liquidation of the former British-administered Mandate of Palestine, the departure of the British and the "Independence War" between the Jews in ex-Mandatory Palestine and five Arab states' armies. The Jewish claim to Palestine as a Jewish homeland can be seen as an example of irredentist reclamation of what is considered lost Jewish land by Zionists. These claims are based on ancestral inhabitance (and in some periods sovereignty) in the land and the cultural/religious significance of it in the Hebrew Bible. The latter is particularly relevant to the Israeli claim to Jerusalem. Mandatory Palestine had sizable Jewish and Arab populations before the Second World War.

Judea and Samaria, as they are called in the Bible, were part of the ancient Kingdom of Israel (designated the West Bank by Jordan in 1947) and the Gaza Strip, previously annexed by Jordan and occupied by Egypt respectively, were conquered and occupied by Israel in the Six-Day War in 1967. Israel withdrew from Gaza in August 2005; Judea and Samaria (West Bank) remain under Israeli control. Israel has never explicitly claimed sovereignty over any part of the West Bank apart from East Jerusalem, which it unilaterally annexed in 1980. However, the Israeli military supports and defends hundreds of thousands of Israeli citizens who have migrated to the West Bank, incurring criticism by some who otherwise support Israel. The United Nations Security Council, the United Nations General Assembly, and some countries and international organizations continue to regard Israel as occupying Gaza. (See Israeli-Occupied Territories)

The Israeli annexing instrument, the Jerusalem Law—one of the Basic Laws of Israel (Israel does not have a constitution)—declares Jerusalem, "complete and united", to be the capital of Israel. Article 3 of the Basic Law of the Palestinian Authority, which was ratified in 2002 by the Palestinian National Authority and serves as an interim constitution, claims that "Jerusalem is the capital of Palestine". De facto, the Palestinian government administers the parts of the West Bank that Israel has granted it authority over from Ramallah, while the Gaza Strip is administered by the Hamas movement from Gaza.

The United States did not recognize Israeli sovereignty over East Jerusalem until 2017. In Jerusalem, the United States maintained two Consulates General as a diplomatic representation to the city of Jerusalem alone, separate from representation to the state of Israel. One of the Consulates General was established before the 1967 war, and the other in a recently constructed building on the Israeli side of Jerusalem. Moreover, Congress passed the Jerusalem Embassy Act in 1995 that says the US shall move its embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, but allows the president to delay the move every year if it is deemed contrary to national security interests. From 1995 to 2017, every president delayed the move. However, President Donald Trump in December 2017 declared his intention to move the embassy to Jerusalem and in May 2018 the embassy officially did so.[27]

A number of Israelis and Jews regard the East Bank of the Jordan river (which is today the Kingdom of Jordan) as the eastern parts of the Land of Israel (following the revisionist idea) because, according to the Bible, the Israelite tribes of Menasseh, Gad, and Reuben settled on the east bank of the Jordan, and allege that the area was designated a Jewish national home by the League of Nations in the Mandate for Palestine based upon the recognized historical connection of the Jewish people to the land. Cited as an explicit basis not to create, but to reconstitute the historical homeland of the Jewish people as a nation-state roughly analogous to the former Kingdom of Israel subject to change by treaty, capitulation, grant, usage, sufferance or other lawful means, it forms a basis for claims of sovereign jurisdiction.

Japan

Japan claims the two southernmost islands of the Russian-administered Kuril Islands, the island chain north of Hokkaido, annexed by the Soviet Union following World War II. Japan also claims the South Korean-administered Liancourt Rocks, which are known as Takeshima in Japan and have been claimed since the end of the Second World War.

Philippines

The Philippines supports the inclusion of the Spanish East Indies and eastern Sabah as a part of the country's territory. This may also extend to various other proposed scenarios that include any or all of the following: Scarborough Shoal, the Macclesfield Bank, and the Spratly Islands (officially claimed by the government as the Kalayaan Islands).

Spain

Spain maintains a claim on Gibraltar, a British Overseas Territory near the southernmost tip of the Iberian Peninsula, which has been British since the 18th Century.

Gibraltar was captured in 1704, during the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714). The Kingdom of Spain formally ceded the territory in perpetuity to the British Crown in 1713, under Article X of the Treaty of Utrecht. Spain's territorial claim was formally reasserted by the Spanish dictator Francisco Franco in the 1960s and has been continued by successive Spanish governments. In 2002 an agreement in principle on joint sovereignty over Gibraltar between the governments of the United Kingdom and Spain was decisively rejected in a referendum. The British Government now refuses to discuss sovereignty without the consent of the Gibraltarians.[28]

Venezuela

The Guayana Esequiba is a territory administered by Guyana but claimed by Venezuela. It was first included in the Viceroyalty of New Granada and the Captaincy General of Venezuela by Spain, but was later included in Essequibo by the Dutch and in British Guiana by the United Kingdom. Originally, parts of what is now eastern Venezuela were included in the disputed area. This territory of 159,500 km2 (61,600 sq mi) is the subject of a long-running boundary dispute inherited from the colonial powers and complicated by the independence of Guyana in 1966. The status of the territory is subject to the Treaty of Geneva, which was signed by the United Kingdom, Venezuela and British Guiana governments on February 17, 1966. This treaty stipulates that the parties will agree to find a practical, peaceful and satisfactory solution to the dispute.[29]

Major current non-government level irredentist claims

Albania

Greater Albania[30] or Ethnic Albania as called by the Albanian nationalists themselves,[31] is an irredentist concept of lands outside the borders of Albania which are considered part of a greater national homeland by most Albanians,[32] based on claims on the present-day or historical presence of Albanian populations in those areas. The term incorporates claims to most of Kosovo, as well as territories in the neighbouring countries Montenegro, Greece, and North Macedonia. Albanians themselves mostly use the term ethnic Albania instead.[31] According to the Gallup Balkan Monitor 2010 report, the idea of a Greater Albania was supported by the majority of Albanians in Albania (63%), Kosovo (81%) and North Macedonia (53%).[32][33]

In 2012, as part of the celebrations for the 100th Anniversary of the Independence of Albania, Prime Minister Sali Berisha spoke of "Albanian lands" stretching from Preveza in Greece to Preševo in Serbia, and from the Macedonian capital of Skopje to the Montenegrin capital of Podgorica, angering Albania's neighbours. The comments were also inscribed on a parchment that will be displayed at a museum in the city of Vlore, where the country's independence from the Ottoman Empire was declared in 1912.[34]

Armenia

The concept of a United Armenia (classical Armenian: Միացեալ Հայաստան, reformed: Միացյալ Հայաստան, translit. Miatsyal Hayastan) refers to areas within the traditional Armenian homeland—the Armenian Highland—which are currently or have historically been mostly populated by Armenians. This incorporates claims to Western Armenia (eastern Turkey), Nagorno-Karabakh (Artsakh), the landlocked exclave Nakhichevan of Azerbaijan and the Javakheti (Javakhk) region of Georgia.[35] Nagorno-Karabakh and Javakhk are overwhelmingly inhabited by Armenians. Western Armenia and Nakhichevan had significant Armenian populations in the early 20th century, but no longer do. The Armenian population of eastern Turkey was almost completely exterminated during the genocide of 1915, when the millennia-long Armenian presence in the area largely ended and Armenian cultural heritage was mainly destroyed by the Turkish government.[36][37] The territorial claims to Turkey are often seen as the ultimate goal of the recognition of the Armenian Genocide and the hypothetical reparations of the genocide.[38][39]

The most recent Armenian irredentist movement, the Karabakh movement that began in 1988, sought to unify Nagorno-Karabakh with then-Soviet Armenia. As a result of the subsequent war with Azerbaijan, the Armenian forces have established effective control over most of Nagorno-Karabakh and the surrounding districts, thus succeeding in de facto unification of Armenia and Karabakh.[40][41]

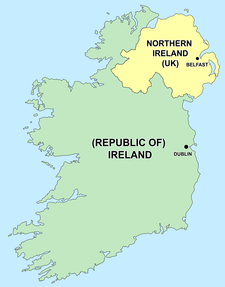

Ireland

The Irish Free State achieved partial independence with a dominion status under the British Empire in 1922. This state did not include Northern Ireland, which comprised six counties in the north-east of the island of Ireland which remained in the United Kingdom. When the Constitution of Ireland was adopted in 1937 it provided that the name of the state is Ireland and this is considered the time that the Republic of Ireland became a fully fledged independent nation. In the constitution Articles 2 and 3 provided that "[t]he national territory consists of the whole island of Ireland", while stipulating that "[p]ending the re-integration of the national territory", the powers of the state were restricted to legislate only for the area which had formed part of the Irish Free State. Arising from the Northern Ireland peace process, the matter was mutually resolved as part of the Good Friday Agreement in 1998. Ireland's constitution was altered by referendum and its territorial claim to Northern Ireland was removed.

The amended constitution asserts that while it is the entitlement of "every person born in the island of Ireland … to be part of the Irish Nation" and to hold Irish citizenship, "a united Ireland shall be brought about only by peaceful means with the consent of a majority of the people, democratically expressed, in both jurisdictions in the island". A North/South Ministerial Council was created between the two jurisdictions and given executive authority. The advisory and consultative role of the government of Ireland in the government of Northern Ireland granted by the United Kingdom, that had begun with the 1985 Anglo-Irish Agreement, was maintained, although that Agreement itself was ended. The two states also settled the long-running dispute concerning their respective names: Ireland and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, with both governments agreeing to use those names.

Under the Irish republican theory of legitimism, the Irish Republic declared in 1916 was in existence from then on, denying the legitimacy of either the state of Ireland or the position of Northern Ireland within the United Kingdom. Through much of its history, this was the position of Sinn Féin; however, it effectively abandoned this stance after accepting the Good Friday Agreement. Small groups which split from Sinn Féin continue to adopt this stance, including Republican Sinn Féin, linked with the Continuity IRA, and the 32 County Sovereignty Movement, linked with the Real IRA.

Historic, theoretical and minor irredentistic claims

Africa

Irredentism is commonplace in Africa due to the political boundaries of former European colonial nation-states passing through ethnic boundaries, and recent declarations of independence after civil war. For example, some Ethiopian nationalist circles still claim the former Ethiopian province of Eritrea (internationally recognized as the independent State of Eritrea in 1993 after a 30-year civil war).

East Africa

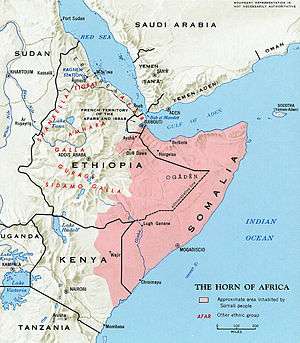

Somalia

Greater Somalia refers to the region in the Horn of Africa in which ethnic Somalis are and have historically represented the predominant population. The territory encompasses The Republic of Somalia, the Ogaden region in Ethiopia, the North Eastern Province in Kenya and southern and eastern Djibouti. Ogaden in eastern Ethiopia has seen military and civic movements seeking to make it part of Somalia. This culminated in the 1977–78 Ogaden War between the two neighbours where the Somali military offensive between July 1977 and March 1978 over the disputed Ethiopian region Ogaden ended when the Somali Armed Forces retreated back across the border and a truce was declared. The Kenyan Northern Frontier District also saw conflict during the Shifta War (1963–1967) when a secessionist conflict in which ethnic Somalis in the Lamu, Garissa, Wajir and Mandera counties (all except Lamu formed part of the former North Eastern Province, abolished in 2013), attempted to join with their fellow Somalis in a "Greater Somalia". There has been no similar conflicts in Djibouti, which was previously known as the "French Somaliland" during colonisation. Here the apparent struggles for unification manifested itself in political strife that ended when in a referendum to join France as opposed to the Somali Republic succeeded among rumours of widespread vote rigging.[42] and the subsequent death of Somali nationalist Mahmoud Harbi, Vice President of the Government Council, who was killed in a plane crash two years later under suspicious circumstances.[43] Some sources say that Somalia has also laid a claim to the Socotra archipelago, which is currently governed by Yemen.

North Africa

In North Africa, the prime examples of irredentism are the concepts of Greater Morocco and Greater Mauritania.[44] While Mauritania has since relinquished any claims to territories outside its internationally recognized borders, Morocco continues to claim Western Sahara, which it refers to as its "Southern Provinces".

Southern Africa

Greater Eswatini includes much of the Mpumalanga Province of South Africa.[45] His Majesty King Mswati III of Eswatini set up the Border Restoration Committee in 2013 to negotiate restoration of the original borders.[46]

Asia

East Asia

China

When Hong Kong and Macau were British and Portuguese territories, respectively, China considered these two territories to be Chinese territories under British and Portuguese administration. Therefore, Hong Kong people and Macau people descended from Chinese immigrants were entitled to Hong Kong Special Administrative Region passport or Macao Special Administrative Region passport after the two territories became the special administrative regions.

Korea

The 1909 Gando Convention addressed a territory dispute between China and Joseon Korea in China's favor. Because the convention was made by the occupying Empire of Japan. Gando Convention was de jure nullified after the Surrender of Japan and North Korea started to control the area south of Paektu Mountain.

In 1961, PR China nominally claims boundary which pass dozens of kilometers south of Paekdu Mountain on PRC's map.[47] North Korea Protested by publishing national map with Gando claim. [48]

However, North Korean claim on Gando and PR Chinese claim on the area south of Gando Convection line were not serious. Seriously disputed area was the area between Gando Convection line and Paektu Mountain.

In 1963, North Korea signed a boundary treaty with the People's Republic of China, which settled the boundary between the two at the Yalu/Amnok (Chinese/Korean names) and Tumen Rivers; this agreement primarily stipulated that three-fifths of Heaven Lake at the peak of Mt. Baekdu would go to North Korea, and two-fifths to China.[49]

South Korea did not recognized these agreements, but did not made serious attempt to gain Korean sovereignty on Gando. South Korea did not officially renounce claim on Gando, but the Sino-Korean boundary on South Korean national map loosely follow 1961 line except Mt. Baekdu and accept this boundary on the map as de facto boundary.

Some Koreans who maintain an irredentist claim on Gando regard Gando as Korean territory because the treaty is null and void.

The most ambitious claims include all parts of Manchuria that the Goguryeo kingdom controlled.

Mongolia

The irredentist idea that advocates cultural and political solidarity of Mongols. The proposed territory usually includes the independent state of Mongolia, the Chinese regions of Inner Mongolia (Southern Mongolia) and Dzungaria (in Xinjiang), and the Russian subjects of Buryatia. Sometimes Tuva and the Altai Republic are included as well.

South Asia

South Asia too is another region in which armed irredentist movements have been active for almost a century. Most prominent amongst them are the Naga fight for Greater Nagaland, the Chin struggle for a unified Chinland, the Sri Lankan Tamil struggle for a return of their state under Tamil Eelam and other self-determinist movements by the ethnic indigenous peoples of the erstwhile Assam both under the British and post-British Assam under India. Other such movements include Beḻagāva border dispute on Maharashtra and Karnataka border with intentions to unite all Marathi speaking people under one state since the formation of the Karnataka state and dissolution of the bilingual Bombay state.

Bangladesh

Greater Bangladesh is an assumption of several Indian intellectuals that the neighbouring country of Bangladesh has an aspiration to unite all Bengali dominated regions under their flag. These include the states of West Bengal, Tripura and Assam as well as the Andaman Islands which are currently part of India and the Burmese State of Rakhine. The theory is principally based on a widespread belief amongst Indian masses that a large number of illegal Bangladeshi immigrants reside in Indian territory. It is alleged that illegal immigration is actively encouraged by some political groups in Bangladesh as well as the state of Bangladesh to convert large parts of India's northeastern states and West Bengal into Muslim-majority areas that would subsequently seek to separate from India and join Muslim-majority Bangladesh.

Scholars have reflected that under the guise of anti-Bangladeshi immigrant movement it is actually an anti-Muslim agenda pointed towards Bangladeshi Muslims by false propaganda and widely exaggerated claims on immigrant population. In 1998, Lieutenant General S.K. Sinha, then the Governor of Assam, claimed that massive illegal immigration from Bangladesh was directly linked with "the long-cherished design of Greater Bangladesh".

India

The call for creation of Akhanda Bharata or Akhand Hindustan has on occasion been raised by some Indian right wing Hindutvadi cultural and political organisations, such as the Hindu Mahasabha, Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), Vishwa Hindu Parishad, Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).[23][24][25][50] The name of one organisation sharing this goal, the Akhand Hindustan Morcha, bears the term in its name.[51] Other major Indian non-sectarian political parties, such as the Indian National Congress, maintain a position against the partition of India .

Iran

Pan-Iranism is an ideology that advocates solidarity and reunification of Iranian peoples living in the Iranian plateau and other regions that have significant Iranian cultural influence, including the Persians, Azerbaijanis, Ossetians, Kurds, Zazas, Tajiks of Tajikistan and Afghanistan, the Pashtuns and the Baloch of Pakistan. The first theoretician was Dr Mahmoud Afshar Yazdi.[53][54][55][56][57][58]

The ideology of pan-Iranism is most often used in conjunction with the idea of forming a Greater Iran, which refers to the regions of the Caucasus, West Asia, Central Asia, and parts of South Asia that have significant Iranian cultural influence due to having been either long historically ruled by the various Iranian (Persian) empires (such as those of the Medes, Achaemenids, Parthians, Sassanians, Samanids, Timurids, Safavids, and Afsharids and the Qajar Empire),[59][60][61] having considerable aspects of Persian culture in their own culture due to extensive contact with the various Empires based in Persia (e.g., those regions and peoples in the North Caucasus that were not under direct Iranian rule), or are simply nowadays still inhabited by a significant amount of Iranic-speaking people who patronize their respective cultures (as it goes for the western parts of South Asia, Bahrain and China). It roughly corresponds to the territory on the Iranian plateau and its bordering plains.[52][62] It is also referred to as Greater Persia,[63][64][65] while the Encyclopædia Iranica uses the term Iranian Cultural Continent.[66]

Nepal

Greater Nepal involves the incorporation of the territories won by the Kingdom of Nepal at it greatest extent back to the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal.

Pakistan

Pakistani irredentism involves the incorporations of Muslim majority lands of British India under Pakistan. This is most notable in the conflict in the Jammu and Kashmir state, a Muslim majority state in India.

Western Asia

Assyria

The Assyrian homeland is a geographic and cultural region situated in Northern Mesopotamia that has been traditionally inhabited by Assyrian people. The area with the greatest concentration of Assyrians on earth is located in the Assyrian homeland, or the Assyrian Triangle, a region which comprises the Nineveh plains, southern Hakkari and the Barwari regions.[67] This is where some Assyrian groups seek to create an independent nation state.[68] The land roughly mirrors the boundaries of ancient Assyria proper, and the later Achaemenid, Seleucid, Parthian, Roman and Sassanid provinces of Assyria (Athura/Assuristan) that was extant between the 25th century BC and 7th century AD.[69]

Azerbaijan

Whole Azerbaijan is a concept of the political and historical union of territories currently and historically inhabited by Azerbaijanis or historically controlled by them.[70] Western Azerbaijan is an irredentist political concept that is used in Azerbaijan mostly to refer to Armenia. Azerbaijani statements claim that the territory of the modern Armenian republic were lands that once belonged to Azerbaijanis.[71]

Caucasus

Irredentism is acute in the Caucasus region. The Nagorno-Karabakh movement's original slogan of miatsum ('union') was explicitly oriented towards re-unification with Armenia as to the pre-Soviet status, feeding an Azerbaijani understanding of the conflict as a bilateral one between itself and an irredentist Armenia.[72][73][74][75][76] According to Prof. Thomas Ambrosio, "Armenia's successful irredentist project in the Nagorno-Karabakh region of Azerbaijan" and "From 1992 to the cease-fire in 1994, Armenia encountered a highly permissive or tolerant international environment that allowed its annexation of some 15 percent of Azerbaijani territory".[77]

In the view of Nadia Milanova, Nagorno-Karabakh represents a combination of separatism and irredentism.[78] However, the area has historically been Armenian, known as the Kingdom of Artsakh or Khachen. When the Caucuses came under the rule of the Soviet Union, the land was given to Azerbaijan abruptly and arbitrarily due to pressure by Joseph Stalin, along with the ancient Armenian lands of Nakhichevan, to appease Turkey during 1919–1921. Azerbaijan's irredentism, on the other hand, is quite explicit in official statements of the Azerbaijani officials by claiming the UN member-state Republic of Armenia as Azerbaijani territory despite the absence of historical evidence of Azerbaijan existing as a separate state up until 1918. On his official meeting in Gyanja on 21 January 2014, President Ilham Aliyev said, "The present-day Armenia is actually located on historical lands of Azerbaijan. Therefore, we will return to all our historical lands in the future. This should be known to young people and children. We must live, we live and we will continue to live with this idea."[79]

Iraq

.svg.png)

After gaining independence in 1932, the Iraqi government immediately declared that Kuwait was rightfully a territory of Iraq, claiming it had been part of an Iraqi territory until being created by the British.[80]

The Qassim government held an irredentist claim to Khuzestan.[81] It also held irredentist claims to Kuwait.[82]

Saddam Hussein's government sought to annex several territories. In the Iran-Iraq War, Saddam claimed that Iraq had the right to hold sovereignty to the east bank of the Shatt al-Arab river held by Iran.[83] Iraq had officially agreed to a compromise to hold the border at the centre-line of the river in the 1975 Algiers Agreement in return for Iran to end its support for Kurdish rebels in Iraq.[83] The overthrow of the Iranian monarchy and the rise of Ruhollah Khomeini to power in 1979 deteriorated Iran-Iraq relations and following ethnic clashes within Khuzestan and border clashes between Iranian and Iraqi forces, Iraq regarded the Algiers Agreement as nullified and abrogated it and a few days later Iraqi forces launched a full-scale invasion of Iran that resulted in the Iran-Iraq War.[83] In addition, Saddam supported the Iraq-based Ahwaz Liberation Movement and their goal of breaking their claimed territory of Ahwaz away from Iran, in the belief that the movement would rouse Khuzestan's Arabs to support the Iraqi invasion.[84] In the Gulf War, Iraq occupied and annexed Kuwait before being expelled by an international military coalition that supported the restoration of Kuwait's sovereignty.

After annexing Kuwait, Iraqi forces amassed on the border with Saudi Arabia, with foreign intelligence services suspected that Saddam was preparing for an invasion of Saudi Arabia to capture or attack its oil fields that were a very short distance from the border.[85] It has been suspected that Saddam Hussein intended to invade and annex a portion of Saudi Arabia's Eastern Province on the justification that the Saudi region of Al-Hasa had been part of the Ottoman province of Basra that the British had helped Saudi Arabia conquer in 1913.[86] It is believed that Saddam intended to annex Kuwait and the Al-Hasa oil region, so that Iraq would be in control of the Persian Gulf region's vast oil production, that would make Iraq the dominant power in the Middle East.[87] The Saudi Arabian government was alarmed by Iraq's mobilization of ten heavily armed and well-supplied Iraqi army divisions along the border of Iraqi-annexed Kuwait and Saudi Arabia, and warned the United States government that they believed that Iraq was preparing for an immediate invasion of Saudi Arabia's Eastern Province.[88] The Saudi Arabian government stated that without assistance from outside forces, Iraq could invade and seize control of the entire Eastern Province within six hours.[88]

Lebanon

The Lebanese nationalism incorporates irredentist views seeking to unify all the lands of ancient Phoenicia around present day Lebanon.[89] This comes from the fact that present day Lebanon, the Mediterranean coast of Syria, and northern Israel is the area that roughly corresponds to ancient Phoenicia and as a result the majority of the Lebanese people identify with the ancient Phoenician population of that region.[90] The proposed Greater Lebanese country includes Lebanon, Mediterranean coast of Syria, and northern Israel.

Syria

The French Mandate of Syria handed over the Sanjak of Alexandretta to Turkey which turned it into Hatay Province. Syria disputes this and still regards the region as belonging to Syria.

The Syrian Social Nationalist Party, which operates in Lebanon and Syria, works for the unification of most modern states of the Levant and beyond in a single state referred to as Greater Syria.[91] The proposed Syrian country includes Israel, Syria, Jordan, and parts of Turkey, and has at times been expanded to include Iraq, Cyprus, and the Sinai peninsula.

Turkey

Misak-ı Millî is the set of six important decisions made by the last term of the Ottoman Parliament. Parliament met on 28 January 1920 and published their decisions on 12 February 1920. These decisions worried the occupying Allies, resulting in the Occupation of Constantinople by the British, French and Italian troops on 16 March 1920 and the establishment of a new Turkish nationalist parliament, the Grand National Assembly, in Ankara.

The Ottoman Minister of Internal Affairs, Damat Ferid Pasha, made the opening speech of parliament due to Mehmed VI's illness. A group of parliamentarians called Felâh-ı Vatan was established by Mustafa Kemal's friends to acknowledge the decisions taken at the Erzurum Congress and the Sivas Congress. Mustafa Kemal said "It is the nation's iron fist that writes the Nation's Oath which is the main principle of our independence to the annals of history." Decisions taken by this parliament were used as the basis for the new Turkish Republic's claims in the Treaty of Lausanne.

United Arab Emirates

The Greater and Lesser Tunbs are disputed by the United Arab Emirates against Iran.

Yemen

Greater Yemen is a theory giving Yemen claim to former territories that were held by various predecessor states that existed between the Himyarite period and 18th century. The areas claimed include parts of modern Saudi Arabia and Oman.

Europe

Bulgaria

Based on the territorial definition of a historic Bulgarian state, a "Greater Bulgaria" nationalist movement has been active for more than a century that would annex most of Macedonia, Thrace, and Moesia.

Finland

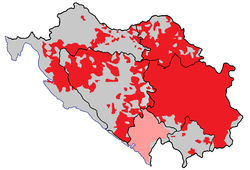

Former Yugoslavia

Some of the most violent irredentist conflicts of recent times in Europe flared up as a consequence of the break-up of the former Yugoslavian federal state in the early 1990s. The conflict erupted further south with the ethnic Albanian majority in Kosovo seeking to switch allegiance to the adjoining state of Albania.[92]

Greater Serbia is a Serbian nationalist ideology. Greater Serbia consists of Serbia, North Macedonia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro and large parts of Croatia.

France

Germany

During the debate of what was then called the German Question (die deutsche Frage) in the 19th century prior to the unification of Germany (1871), the term Großdeutschland, "Greater Germany", referred to a possible German nation consisting of the states that later comprised the German Empire and Austria. The term Kleindeutschland "Lesser Germany" referred to a possible German state without Austria. The term was later used by Germans referring to Greater Germany, a state consisting of pre–World War I Germany, Austria and the Sudetenland.

A main point of Nazi ideology was to reunify all Germans either born or living outside of Germany to create an "all-German Reich". These beliefs ultimately resulted in the Munich Agreement, which ceded to Germany areas of Czechoslovakia that were mainly inhabited by those of German descent, and the Anschluss, which ceded the entire country of Austria to Germany; both events occurred in 1938.

Greece

Following the Greek War of Independence in 1821–1832, Greece began to contest areas inhabited by Greeks, primarily against the Ottoman Empire. The Megali Idea (Great Idea) envisioned Greek incorporation of Greek-inhabited lands, but also historical lands in Asia Minor corresponding with the predominantly Greek and Orthodox Byzantine Empire and the dominions of the ancient Greeks.

The Greek quest began with the acquisition of Thessaly through the Convention of Constantinople in 1881, a failed war against Turkey in 1897 and the Balkan Wars (Macedonia, Epirus, some Aegean Islands). After World War I, Greece acquired Western Thrace from Bulgaria as per the Treaty of Neuilly-sur-Seine, but also Ionia/Smyrna and Eastern Thrace (excluding Constantinople) from the Ottoman Empire as ordained in the Treaty of Sèvres. Subsequently, Greece launched an unsuccessful campaign to further their gains in Asia Minor, but were halted by the Turkish revolution. The events culminated into the Great Fire of Smyrna, Population exchange between Greece and Turkey, and Treaty of Lausanne (1923) which returned Eastern Thrace and Ionia to the newfound Turkish Republic. The events are known as the "Asia Minor Catastrophe" to Greeks. The Ionian Islands were ceded by Britain in 1864, and the Dodecanese by Italy in 1947.

Another concern of the Greeks is the incorporation of Cyprus which was ceded by the Ottomans to the British. As a result of the Cyprus Emergency the island gained independence as the Republic of Cyprus in 1960. The failed incorporation by Greece through coup d'état and the Turkish invasion of Cyprus in 1974 led to the formation of the mostly unrecognized Northern Cyprus and has culminated into the present-day Cyprus issue.

The Aegean islands of Imbros and Tenedos which were not ceded to Greece over the course of the 20th century and where the dominant Greek community has faced persecution are also of concern.

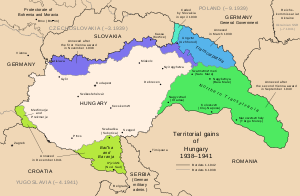

Hungary

The restoration of the borders of Hungary to their state prior to World War I, in order to unite all ethnic Hungarians within the same country once again.

Hungarian irredentism or Greater Hungary are irredentist and revisionist political ideas concerning redemption of territories of the historical Kingdom of Hungary. The idea is associated with Hungarian revisionism, targeting at least to regain control over Hungarian-populated areas in Hungary's neighbouring countries. Hungarian historians did not use the term Greater Hungary, because the "Historic Hungary" is the established term for the Kingdom of Hungary before 1920.

The Treaty of Trianon defined the borders of the new independent Hungary and, compared against the claims of the pre-war Kingdom, new Hungary had approximately 72% less land stake and about two-thirds fewer inhabitants, almost 5 million of these being of Hungarian ethnicity.[93][94] However, only 54% of the inhabitants of the pre-war Kingdom of Hungary were Hungarians before World War I.[95][96] Following the treaty's instatement, Hungarian leaders became inclined towards revoking some of its terms. This political aim gained greater attention and was a serious national concern up through the second World War.[97]

Irredentism in the 1930s led Hungary to form an alliance with Hitler's Germany. Eva S. Balogh states: "Hungary's participation in World War II resulted from a desire to revise the Treaty of Trianon so as to recover territories lost after World War I. This revisionism was the basis for Hungary's interwar foreign policy."[98]

Between November 1938 and April 1941, Hungary took full advantage of German patronage and, in four different stages, approximately doubled her size. Ethnically, these acquisitions were a mixed bag, some were populated mostly by Hungarians, while others, such as the remainder of Carpathian Ruthenia, were almost wholly non-Hungarian in composition. However, regarding partitioned Transylvania, the population was mixed, near equal between Hugarians and non-Hungarians.[99]

Hungary began with the First Vienna Award in 1938 (redeeming southern Czechoslovakia with mainly Hungarians) and the Second Vienna Award in 1940 (Northern Transylvania). Through military campaigns it gained the remainder of Carpathian Ruthenia in 1939. In 1941 it added the Yugoslav parts of Bačka, Baranja, Međimurje, and Prekmurje.

After defeat in 1945, the borders of Hungary as defined by the Treaty of Trianon were restored, except for three Hungarian villages that were transferred to Czechoslovakia. These villages are today administratively a part of Bratislava.[100]

Italy

Italy's territorial claims were on the basis of re-establishing a Romanesque Empire, a fourth shore according to the concept of Mare Nostrum (Latin for 'Our Sea') and traditional ethnic borders. Evident in Italy's rapid takeover of surrounding territories under Fascist leader Benito Mussolini and claims following the collapsed 1915 Treaty of London and 1919 Treaty of Versailles which established feelings of betrayal. Mussolini and Hitler's similarities including a joint hatred towards the French and wanting to expand their territories brought the two leaders together, solidified in the Pact of Steel and later WW2. By 1942 Italy had conquered Abyssinia (modern day Ethiopia and Eritrea), Libya, much of the north coast of Egypt, and what is now Somalia. And – on the European continent, and with significant German assistance, – Istria, Dalmatia, Albania, Slovenia, Croatia, Macedonia, and France's Corsica; Malta was also bombed. Underlying tensions remained with France, over its territories of Corsica, Nice and Savoy.

North Macedonia

Some Macedonian nationalists promoted the irredentist concept of a United Macedonia (Macedonian: Обединета Македонија, romanized: Obedineta Makedonija) among ethnic Macedonian nationalists, which involves territorial claims on the northern province of Macedonia in Greece, but also in Blagoevgrad Province ("Pirin Macedonia") in Bulgaria, Albania, and Serbia. The United Macedonia concept aims to unify the transnational region of Macedonia in the Balkans (which they claim as their homeland and which they assert was wrongfully divided under the Treaty of Bucharest in 1913), into a single state under Macedonian domination, with the Greek city of Thessaloniki (Solun in the Slavic languages) as its capital.[101][102]

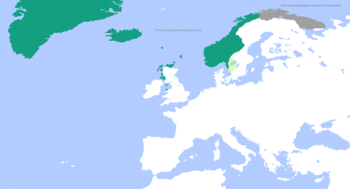

Norway

The Kingdom of Norway maintains some claim to territories lost at the dissolution of the Denmark–Norway union. The Old Kingdom of Norway, which was the Norwegian territories at its maximum extent, included Iceland, the settleable areas of Greenland, the Faroe Islands and Northern Isles (today part of Scotland). Under Danish sovereignty since they established a hegemonic position in the Kalmar Union, the territories were considered as Norwegian colonies. When in the Treaty of Kiel in 1814, Norway's territories were transferred from Denmark to Sweden, the territories of Iceland, Greenland, and the Faroe Islands were maintained by Denmark.

In 1919, Norway declared sovereignty over an area in Eastern Greenland in the Ihlen Declaration, which led to a dispute with Denmark that was not settled until 1933, by the Permanent Court of International Justice. Norway formerly included the provinces Jämtland, Härjedalen, Idre-Särna (lost since the Second Treaty of Brömsebro), and Bohuslän (lost since the Treaty of Roskilde), which were ceded to Sweden after Danish defeats in wars such as the Thirty Years' War and Second Northern War.

Poland

Kresy ("Borderlands") are the eastern lands that formerly belonged to Poland. In 1921, Polish troops crossed the Curzon Line and seized large Ukrainian and Belorussian territories, and also seized 7 percent of Lithuania's territory in 1920. These territories were re-annexed by the Soviet Union in 1939 under the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, and include major cities, like Lviv (Ukraine), Vilnius (the capital of Lithuania), and Hrodna (Belarus). Even though Kresy, or the Eastern Borderlands, are no longer Polish territories, the area is still inhabited by a significant Polish minority, and the memory of the Polish Kresy is still cultivated. The attachment to the "myth of Kresy", the vision of the region as a peaceful, idyllic, rural land, has been criticized in Polish discourse.[103]

In January, February and March 2012, the Centre for Public Opinion Research conducted a survey, asking Poles about their ties to the Kresy. It turned out that almost 15% of the population of Poland (4.3–4.6 million people) declared that they had either been born in the Kresy, or had a parent or a grandparent who came from that region. Numerous treasures of Polish culture remain and there are numerous Kresy-oriented organizations. There are Polish sports clubs (Pogoń Lwów, and formerly FK Polonia Vilnius), newspapers (Gazeta Lwowska, Kurier Wileński), radio stations (in Lviv and Vilnius), numerous theatres, schools, choirs and folk ensembles. Poles living in Kresy are helped by Fundacja Pomoc Polakom na Wschodzie, a Polish government-sponsored organization, as well as other organizations, such as The Association of Help of Poles in the East Kresy (see also Karta Polaka). Money is frequently collected to help those Poles who live in the Kresy, and there are several annual events, such as a Christmas Package for a Polish Veteran in Kresy, and Summer with Poland, sponsored by the Association "Polish Community", in which Polish children from Kresy are invited to visit Poland.[104] Polish language handbooks and films, as well as medicines and clothes are collected and sent to Kresy. Books are most often sent to Polish schools which exist there—for example, in December 2010, The University of Wrocław organized an event called Become a Polish Santa Claus and Give a Book to a Polish Child in Kresy.[105] Polish churches and cemeteries (such as Cemetery of the Defenders of Lwów) are renovated with money from Poland.

Portugal

Portugal does not recognize Spanish sovereignty over the territory of Olivenza, ceded to Spain during the Napoleonic Wars.[106]

Romania

Romanian nationalists lay claims to Greater Romania, but especially to Moldova, most of the territory which was part of the country between 1918 and 1940. Moldovan language is the Soviet name for the Romanian language. There is some (but not universal) support by Moldovans for a peaceful and voluntary reunion with Romania, not least because (having joined the European Union), the economy has burgeoned and Romanian citizens have gained freedom of movement in Europe. Also Russian irredentism in Transnistria has caused alarm and resentment.

Russia

The annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation in 2014 was based on a claim of protecting ethnic Russians residing there. Crimea was part of the Russian Empire from 1783 to 1917, after which it enjoyed a few years of autonomy until it was made part of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (which was a part of the Soviet Union) from 1921 to 1954 and then transferred to Soviet Ukraine (which also was a part of the Soviet Union) in 1954. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Crimea still remained part of Ukraine until February 2014. Russia declared Crimea to be part of the Russian Federation in March 2014, and effective administration commenced. The Russian regional status is not currently recognised by the UN General Assembly and by many countries.

Russian irredentism also includes southeastern and coastal Ukraine, known as Novorossiya, a term from the Russian Empire.

Serbia

Serbian irredentism is manifested in "Greater Serbia". Used in the context of the Yugoslav wars, however, the Serbian struggle for Serbs to remain united in one country does not quite fit the term "irredentism".[107] In the 19th century, Pan-Serbism sought to unite all of the Serb people across the Balkans, under Ottoman and Habsburg rule. Some intellectuals sought to unite all South Slavs (regardless of religion) into a Serbian state. Serbia had gained independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1878. Bosnia and Herzegovina, annexed by the Austrians in 1908, was viewed of as a part of the Serbian homeland. Serbia directed its territorial aspirations to the south, as the north and west was held by Austria. Macedonia was divided between Serbia and Greece after the Balkan Wars.

In 1914, aspirations were directed towards Austria-Hungary. A government policy sought to incorporate all Serb-inhabited areas, and other South Slavic areas, thereby laying the foundation of Yugoslavia.[108] With the establishment of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (later Yugoslavia), the Serbs now lived united in one country.[107] During the breakup of Yugoslavia, the Serb political leadership in break-away Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina declared their territories to be part of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (Serbia and Montenegro).

The project of unification of Serb-inhabited areas in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina during the Yugoslav wars (see United Serb Republic) ultimately failed. The Croatian Operation Storm ended large-scale combat and captured most of the Republic of Serbian Krajina, while the Dayton Agreement ended the Bosnian War. Bosnia and Herzegovina was established as a federal republic, made up by two separate entities, one being Serb-inhabited Republika Srpska. There has since been calls by Bosnian Serb politicians for the secession of Republika Srpska, and possible unification with Serbia.

After the Kosovo War (1998–99), Kosovo became a UN protectorate, still de jure part of Serbia. The Albanian-majority Kosovo assembly unilaterally declared the independence of Kosovo in 2008, and its status is since disputed.

North America

Mexico

In the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848) following the Mexican–American War (1845–48), Mexico ceded claims to what is now the Western and Southwestern United States to the United States (see Mexican Cession). The Cortina and Pizaña uprisings of 1859 and 1915 were influenced by irredentist ideas and the "proximity of the international boundary".[109] The unsuccessful Pizaña uprising "was the last major armed protest on the part of Texas-Americans" (Tejanos).[110] This 1915 uprising and the Plan of San Diego that preceded it marked the high point in Mexican irredentist sentiments.[111][112]

In the early years of the Chicano Movement (El Movimiento) in the 1960s and 1970s, some movement figures "were political nationalists who advocated the secession of the Southwest from the Anglo republic of the United States of America, if not fully, at least locally with regard to Chicano self-determination in local governance, education and means of production".[113] For example, in the 1970s, Reies Tijerina and his group La Alianza, espoused various separatist, secessionist, or irredentist beliefs.[114] The Plan Espiritual de Aztlán, written during the First Chicano National Youth Conference in 1969, also stated "the fundamental Chicano nationalist goal of reclaiming Aztlán"—a reference to ancient Mexican myth—as "the rightful homeland of the Chicanos".[113] However, "Most Chicano nationalists ... did not express the extreme desire for secession from the United States, and the nationalism they expressed weighed more heavily toward the broadly cultural than the explicitly political."[113]

Today, there is virtually no Mexican-American support for "separatist policies of self-determination".[115] "Ethnonational irredentism by Mexicans in territories seized by the United States" following the Mexican–American War "declined after the failure of several attempted revolts at the end of the nineteenth century, in favor of internal ... struggles for immigrant and racial civil rights" in the United States.[116] Neither the Mexican government nor any significant Mexican-American group "makes irredentist claims upon the United States".[117] In the modern era, there "has been no evidence of irredentist sentiments among Mexican-Americans, even in such formerly Mexican territories as Southern California, ... nor of disloyalty to the United States, nor of active interest in the politics of Mexico".[118]

Border disputes and state expansionism loosely related to irredentist claims

Afghanistan

The Afghan border with Pakistan, known as the Durand Line, was agreed to by Afghanistan and British India in 1893. The Pashtun tribes inhabiting the border areas were divided between what have become two nations; Afghanistan never accepted the still-porous border and clashes broke out in the 1950s and 1960s between Afghanistan and Pakistan over the issue. All Afghan governments of the past century have declared, with varying intensity, a long-term goal of re-uniting all Pashtun-dominated areas under Afghan rule,[119][120] although no other country in the world accepts Afghanistan's unilateral claim that the Durand Line is in dispute. Afghan claims over Pakistani territory have negatively affected Afghanistan–Pakistan relations.

Korea

Since their founding, both Korean states have disputed the legitimacy of the other. North Korea's constitution stresses the importance of reunification, but, while it makes no similar formal provision for administering the South, it effectively claims its territory as it does not diplomatically recognise the Republic of Korea, deeming it an "entity occupying the Korean territory".

South Korea's constitution also claims jurisdiction over the entire Korean peninsula. It acknowledges the division of Korea only indirectly by requiring the president to work for reunification. The Committee for the Five Northern Korean Provinces, established in 1949, is the South Korean authority charged with the administration of Korean territory north of the Military Demarcation Line (i.e., North Korea), and consists of the governors of the five provinces, who are appointed by the President. However the body is purely symbolic and largely tasked with dealing with Northern defectors; if reunification were to occur the Committee would be dissolved and new administrators appointed by the Ministry of Unification.[121]

Pakistan

Pakistan has from its inception sought to have the territory of Kashmir incorporated into it. This singular demand has predominated Pakistan's policy strategy and decision-making as well as its diplomacy, throughout its existence. Pakistan's dispute with India over the territory of Kashmir stems from events leading up to the 1948 war between the 2 countries.

See also

References

- Kornprobst, Markus (2008-12-18). Irredentism in European Politics: Argumentation, Compromise and Norms. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89558-3.

- "Irredentism". Merriam_Webster dictionary. Retrieved 14 February 2020.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 14 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 840.

- Bozeman., Adda Bruemmer (1949). Regional Conflicts Around Geneva: An Inquiry Into the Origin, Nature, and Implications of the Neutralized Zone of Savoy and of the Customs-free Zones of Gex and Upper Savoy. Geneva. ISBN 9780804705127.

- "Irredenta". Free Dictionary.

- "WAR AND NATION: IDENTITY AND THE PROCESS OF STATE-BUILDING IN SOUTH AMERICA (1800-1840)". Leverhulme Trust. University of Kent. Retrieved 28 September 2019.

- "CONSTITUTION OF THE ARGENTINE NATION". pp. Temporary Provisions. Archived from the original on 2011-06-04. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- "Argentina presses claim to Falkland Islands, accusing UK of colonialism". CNN. Retrieved 2012-01-08.

- "Constitución Nacional" (in Spanish). 22 August 1994. Archived from the original on June 17, 2004. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- "Constitution of the Argentine Nation". 22 August 1994. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- Christophe Jaffrelot (2004). A History of Pakistan and Its Origins. Anthem Press. p. 42. ISBN 9781843311492.

- "Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy : His Life". thedailynewnation.com. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- CAPÍTULO CUARTO, REIVINDICACIÓN MARÍTIMA. Artículo 267. I. El Estado boliviano declara su derecho irrenunciable e imprescriptible sobre el territorio que le dé acceso al océano Pacífico y su espacio marítimo. II. La solución efectiva al diferendo marítimo a través de medios pacíficos y el ejercicio pleno de la soberanía sobre dicho territorio constituyen objetivos permanentes e irrenunciables del Estado boliviano.Constitution of Bolivia Archived 2017-10-24 at the Wayback Machine

- "The One-China Principle and the Taiwan Issue". PRC Taiwan Affairs Office and the Information Office of the State Council. 2005. Archived from the original on 13 February 2006. Retrieved 2006-03-06.

- Horton, Chris (2 September 2018). "Once a Cold War Flashpoint, a Part of Taiwan Embraces China's Pull". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- "Treaty of Shimonoseki". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2018. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- Wright, David Curtis (2011-01-01). The History of China. ABC-CLIO. p. 113. ISBN 9780313377488.

In May 1985 a short lived republic was declared in Taiwan...

- "Republic of Formosa. Most Short-Lived Government That Has Ever Existed". Sacramento Daily Record-Union. Sacramento. 20 July 1895. p. 8.

Denby confirms the statement made that a republican form of government was instituted, and says: "This republic will pass into history as the most short-lived government that ever existed. ......"

- "Taiwan". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2019. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- The National Assembly abolished in 2005, which transfer power to the Legislative Yuan. The Legislative Yuan hold the power for decide to have a referendum about the changes of territory.

- UN General Assembly, Forty-ninth session: Agenda item 36 Archived May 27, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Security Council S/PV. 1888 para 247 S/11967 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-03-17. Retrieved 2006-11-13.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) "Archived copy". Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-03-17. Retrieved 2013-10-21.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Yale H. Ferguson and R. J. Barry Jones, Political space: frontiers of change and governance in a globalizing world, page 155, SUNY Press, 2002, ISBN 978-0-7914-5460-2

- Sucheta Majumder, "Right Wing Mobilization in India", Feminist Review, issue 49, page 17, Routledge, 1995, ISBN 978-0-415-12375-4

- Ulrika Mårtensson and Jennifer Bailey, Fundamentalism in the Modern World (Volume 1), page 97, I.B.Tauris, 2011, ISBN 978-1-84885-330-0

- McIntyre, Angus (1973). "The 'Greater Indonesia' Idea of Nationalism in Malaysia and Indonesia". Modern Asian Studies. 7 (1): 75–83. doi:10.1017/S0026749X0000439X.

- Mark Landler (6 December 2017). "Trump Recognizes Jerusalem as Israel's Capital and Orders U.S. Embassy to Move". The New York Times.

- The Committee Office, House of Commons. "Answer to Q257 at the FAC hearing". Publications.parliament.uk. Retrieved 2013-08-05.

- "Agreement to resolve the controversy over the frontier between Venezuela and British Guiana (Treaty of Geneva, 1966)" (PDF). United Nations.

- "404 Error Page" (PDF). www.da.mod.uk.

- Bogdani, Mirela; John Loughlin (2007). Albania and the European Union: the tumultuous journey towards integration. IB Taurus. p. 230. ISBN 978-1-84511-308-7. Retrieved 2010-05-28.

- Likmeta, Besar (17 November 2010). "Poll Reveals Support for 'Greater Albania'". Balkan Insight.

- "Balkan Monitor: Insights and Perceptions: Voices of The Balkans" (PDF). Gallup. 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 December 2010.

- Albania celebrates 100 years of independence, yet angers half its neighbors Associated Press, November 28, 2012.

- "Armenia: Internal Instability Ahead" (PDF). Yerevan/Brussels: International Crisis Group. 18 October 2004. p. 8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 11 June 2014.

The Dashnaktsutiun Party, which has a major following within the diaspora, states as its goals: "The creation of a Free, Independent, and United Armenia. The borders of United Armenia shall include all territories designated as Armenia by the Treaty of Sevres as well as the regions of Artzakh [the Armenian name for Nagorno-Karabakh], Javakhk, and Nakhichevan".

- Hovannisian, Richard G. (2008). The Armenian Genocide: Cultural and Ethical Legacies. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-4128-3592-3.

- Jones, Adam (2013). Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction. Routledge. p. 114. ISBN 978-1-134-25981-6.

- Theriault, Henry (6 May 2010). "The Global Reparations Movement and Meaningful Resolution of the Armenian Genocide". The Armenian Weekly. Archived from the original on 10 May 2010.

- Stepanyan, S. (2012). "Հայոց ցեղասպանության ճանաչումից ու դատապարտումից մինչև Հայկական հարցի արդարացի լուծում [From the Recognition and Condemnation of the Armenian Genocide to the Just Resolution of the Armenian Question]". Lraber Hasarakakan Gitutyunneri (in Armenian). Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences (1): 34. ISSN 0320-8117.

Արդի ժամանակներում Հայկական հարցը իր էությամբ նպատակամղված է Թուրքիայի կողմից արևմտահայության բնօրրան, ցեղասպանության և տեղահանության ենթարկված Արևմտյան Հայաստանը` հայրենիքը կորցրած հայերի ժառանգներին և Հայաստանի Հանրապետությանը վերադարձնելուն:

- Ambrosio 2001, p. 146: "... Armenia's successful irrendentist project in the Nagorno-Karabakh region of Azerbaijan."

- Hughes, James (2002). Ethnicity and Territory in the Former Soviet Union: Regions in Conflict. London: Cass. p. 211. ISBN 978-0-7146-8210-5.

Indeed, Nagorno-Karabakh is de facto part of Armenia.

- Africa Research, Ltd (1966). Africa Research Bulletin, Volume 3. Blackwell. p. 597. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- Barrington, Lowell, After Independence: Making and Protecting the Nation in Postcolonial and Postcommunist States, (University of Michigan Press: 2006), p.115

- http://www.bundesheer.at/pdf_pool/publikationen/hasa03.pdf

- "Swazi History - Olden Times - Swaziland National Trust Commission". www.sntc.org.sz.

- "BORDER RESTORATION COMMITTEE". Times of Swaziland. November 25, 2013.

- 金得榥,「백두산과 북방강계」, 사사연, 1987, 27쪽

- 북한연구소, 북한총람 (1982) 85쪽.

- Border Disputes with China and North Korea. http://chinaperspectives.revues.org/806

- Suda, Jyoti Prasad (1953). India, Her Civic Life and Administration. Jai Prakash Nath & Co. Retrieved 23 July 2014.

Its members still swear by the ideal of Akhand Hindustan.

- Hindu Political Parties. General Books. 30 May 2010. ISBN 9781157374923.

- "IRAN i. LANDS OF IRAN". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- Professor Richard Frye states: The Turkish speakers of Azerbaijan are mainly descended from the earlier Iranian speakers, several pockets of whom still exist in the region (Frye, Richard Nelson, "Peoples of Iran", in Encyclopedia Iranica).

- Swietochowski, Tadeusz. "AZERBAIJAN, REPUBLIC OF", Vol. 3, Colliers Encyclopedia CD-ROM, 02-28-1996: "The original Persian population became fused with the Turks, and gradually the Persian language was supplanted by a Turkic dialect that evolved into the distinct Azerbaijani language."

- Golden, P.B. "An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples", Otto Harrosowitz, 1992. "The Azeris of today are an overwhelmingly sedentary, detribalized people. Anthropologically, they are little distinguished from the Iranian neighbor"

- de Planhol, Xavier. "Iran i. Lands of Iran". Encyclopedia Iranica.

The toponymy, with more than half of the place names of Iranian origin in some areas, such as the Sahand, a huge volcanic massif south of Tabriz, or the Qara Dagh, near the border (Planhol, 1966, p. 305; Bazin, 1982, p. 28) bears witness to this continuity. The language itself provides eloquent proof. Azeri, not unlike Uzbek (see above), lost the vocal harmony typical of Turkish languages. It is a Turkish language learned and spoken by Iranian peasants.

- "Thus Turkish nomads, in spite of their deep penetration throughout Iranian lands, only slightly influenced the local culture. Elements borrowed by the Iranians from their invaders were negligible."(X.D. Planhol, LANDS OF IRAN in Encyclopedia Iranica)

- История Востока. В 6 т. Т. 2. Восток в средние века. Глава V. — М.: «Восточная литература», 2002. — ISBN 5-02-017711-3. Excerpt: "Говоря о возникновении азербайджанской культуры именно в XIV-XV вв., следует иметь в виду прежде всего литературу и другие части культуры, органически связанные с языком. Что касается материальной культуры, то она оставалась традиционной и после тюркизации местного населения. Впрочем, наличие мощного пласта иранцев, принявших участие в формировании азербайджанского этноса, наложило свой отпечаток прежде всего на лексику азербайджанского языка, в котором огромное число иранских и арабских слов. Последние вошли и в азербайджанский, и в турецкий язык главным образом через иранское посредство. Став самостоятельной, азербайджанская культура сохранила тесные связи с иранской и арабской. Они скреплялись и общей религией, и общими культурно-историческими традициями." (History of the East. 6 v. 2. East during the Middle Ages. Chapter V. – M.: «Eastern literature», 2002. – ISBN 5-02-017711-3.). Translation: "However, the availability of powerful layer of Iranians took part in the formation of the Azerbaijani ethnic group, left their mark primarily in the Azerbaijani language, in which a great number of Iranian and Arabic words. The latter included in the Azeri, and Turkish language primarily through Iranian mediation."

- Marcinkowski, Christoph (2010). Shi'ite Identities: Community and Culture in Changing Social Contexts. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 83. ISBN 978-3-643-80049-7.

- "Interview with Richard N. Frye (CNN)". 2007. Archived from the original on 2016-04-23. Retrieved 2017-04-19.

- Frye, Richard Nelson (October 1962). "Reitzenstein and Qumrân Revisited by an Iranian". The Harvard Theological Review. 55 (4): 261–268. doi:10.1017/S0017816000007926. JSTOR 1508723.

I use the term Iran in an historical context [...] Persia would be used for the modern state, more or less equivalent to "western Iran". I use the term "Greater Iran" to mean what I suspect most Classicists and ancient historians really mean by their use of Persia – that which was within the political boundaries of States ruled by Iranians

- Dialect, Culture, and Society in Eastern Arabia: Glossary. Clive Holes. 2001. Page XXX. ISBN 90-04-10763-0

- Lange, Christian (19 July 2012). Justice, Punishment and the Medieval Muslim Imagination. Cambridge Studies in Islamic Civilization. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107404618.

I further restrict the scope of this study by focusing on the lands of Iraq and greater Persia (including Khwārazm, Transoxania, and Afghanistan).

- Gobineau, Joseph Arthur; O'Donoghue, Daniel. Gobineau and Persia: A Love Story. ISBN 1-56859-262-0. Archived from the original on 2011-07-23. O'Donoghue: "... all set in the greater Persia/Iran which includes Afghanistan".

- Shiels, Stan (2004). Stan Shiels on centrifugal pumps: collected articles from "World Pumps" magazine. Elsevier. pp. 11–12, 18. ISBN 1-85617-445-X. Shiels: "During the Sassanid period the term Eranshahr was employed to denote the region also known as Greater Iran ..." Also: "... the Abbasids, who with Persian assistance assumed the Prophet's mantle and transferred their capital to Baghdad three years later; thus, on a site close to historic Ctesiphon and even older Babylon, the caliphate was established within the bounds of Greater Persia."

- "Columbia College Today". columbia.edu. Archived from the original on 27 November 2015. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- The Origins of War: From the Stone Age to Alexander the Great By Arther Ferrill – p. 70

- Minorities in the Middle East: a history of struggle and self-expression By Mordechai Nisan

- Donabed, Sargon (1 February 2015). Reforging a Forgotten History: Iraq and the Assyrians in the Twentieth Century. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9780748686056 – via Google Books.

- "Diaspora agrees to reintegrate Iranian Azerbaijan in Republic of Azerbaijan". abc.az. Archived from the original on 5 February 2016. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- "Present-day Armenia located in ancient Azerbaijani lands – Ilham Aliyev". News.Az. October 16, 2010. Archived from the original on July 21, 2015.

- Patrick Barron. "Dr Laurence Broers, The resources for peace: comparing the Karabakh, Abkhazia and South Ossetia peace processes, Conciliation Resources, 2006". C-r.org. Retrieved 2014-05-21.

- CRIA. "Fareed Shafee, Inspired from Abroad: The External Sources of Separatism in Azerbaijan, Caucasian Review of International Affairs, Vol. 2 (4) – Autumn 2008, pp. 200–211". Cria-online.org. Archived from the original on 2011-10-03. Retrieved 2014-05-21.

- What is Irredentism? Archived 2014-02-22 at the Wayback Machine SEMP, Biot Report #224, USA, June 21, 2005

- "Saideman, Stephen M. and R. William Ayres, For Kin and Country: Xenophobia, Nationalism and War, New York, N.Y.: Columbia University Press, 2008" (PDF). Retrieved 2014-05-21.

- Irredentism enters Armenia's foreign policy, Jamestown Foundation Monitor Volume: 4 Issue: 77, Washington DC, April 22, 1998

- Prof. Thomas Ambrosio, Irredentism: ethnic conflict and international politics, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001

- Milanova, Nadia (2003). "The Territory-Identity Nexus in the Conflict over Nagorno Karabakh". Flensburg, Germany: European Centre for Minority Issues. p. 2. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

The conflict over Nagorno Karabakh, defined as an amalgam of separatism and irredentism ...

- "President.Az -". en.president.az. Archived from the original on 2016-08-20. Retrieved 2016-08-15.

- Duiker, William J; Spielvogel, Jackson J. World History: From 1500. 5th edition. Belmont, California, USA: Thomson Wadsworth, 2007. Pp. 839.

- Helen Chapin Metz. Iraq A Country Study. Kessinger Publishing, 2004 Pp. 65.

- Raymond A. Hinnebusch. The international politics of the Middle East. Manchester, England, UK: Manchester University Press, 2003 Pp. 209.

- Erik Goldstein, Erik (Dr.). Wars and Peace Treaties: 1816 to 1991. P133.

- Kevin M. Woods, David D. Palkki, Mark E. Stout. The Saddam Tapes: The Inner Workings of a Tyrant's Regime, 1978-2001. Cambridge University Press, 2011. Pp. 131-132

- Nathan E. Busch. No End in Sight: The Continuing Menace of Nuclear Proliferation. Lexington, Kentucky, USA: University of Kentucky Press, 2004. Pp. 237.

- Amatzia Baram, Barry Rubin. Iraq's Road To War. New York, New York, USA: St. Martin's Press, 1993. Pp. 127.

- Sharad S. Chauhan. War On Iraq. APH Publishing, 2003. Pp. 126.

- Middle East Contemporary Survey, Volume 14; Volume 1990. Pp. 606.

- Kaufman, Asher (30 June 2014). Reviving Phoenicia: The Search for Identity in Lebanon. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9781780767796 – via Google Books.

- Kamal S. Salibi, "The Lebanese Identity" Journal of Contemporary History 6.1, Nationalism and Separatism (1971:76–86).

- Pipes, Daniel (August 1988). "Radical Politics and the Syrian Social Nationalist Party". International Journal of Middle East Studies. Retrieved 2017-01-28.

- Chazan, Naomi (1991). Irredentism and international politics. Lynne Rienner Publishers. ISBN 9781555872212.

- Fenyvesi, Anna (2005). Hungarian language contact outside Hungary: studies on Hungarian as a minority language. John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 2. ISBN 90-272-1858-7. Retrieved 2011-08-15.

- "Treaty of Trianon". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- A magyar szent korona országainak 1910. évi népszámlálása. Első rész. A népesség főbb adatai. (in Hungarian). Budapest: Magyar Kir. Központi Statisztikai Hivatal (KSH). 1912.

- Anstalt G. Freytag & Berndt (1911). Geographischer Atlas zur Vaterlandskunde an der österreichischen Mittelschulen. Vienna: K. u. k. Hof-Kartographische. "Census December 31st 1910"

- "HUNGARY". Hungarian Online Resources (Magyar Online Forrás). Archived from the original on 2010-11-24. Retrieved 2011-02-13.

- Eva S. Balogh, "Peaceful Revision: The Diplomatic Road to War." Hungarian Studies Review 10.1 (1983): 43-51. online

- Balogh, p. 44.

- Mark Pittaway, "National socialism and the production of German–Hungarian borderland space on the eve of the second world war." Past & Present 216.1 (2012): 143-180.

- Greek Macedonia "not a problem", The Times (London), August 5, 1957