Paektu Mountain

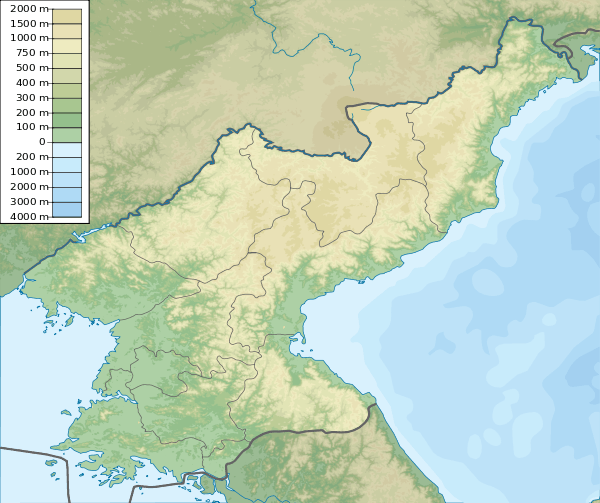

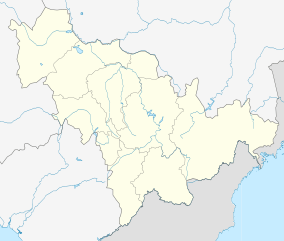

Paektu Mountain (Korean: 백두산), also known as Baekdu Mountain and in China as Changbai Mountain (simplified Chinese: 长白山; traditional Chinese: 長白山), is an active stratovolcano on the Chinese–North Korean border.[2] At 2,744 m (9,003 ft), it is the highest mountain of the Changbai and Baekdudaegan ranges. Koreans assign a mythical quality to the volcano and its caldera lake, considering it to be their country's spiritual home.[3] It is the highest mountain in North Korea, the Korean Peninsula and Northeast China.[4]

| Paektu Mountain | |

|---|---|

| 长白山 백두산 | |

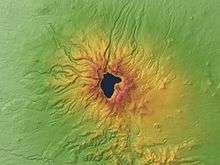

.jpg) The summit caldera of Paektu Mountain, with Heaven Lake | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 2,744 m (9,003 ft) |

| Prominence | 2,593 m (8,507 ft) |

| Listing | Country high point Ultra |

| Coordinates | 42°00′20″N 128°03′19″E |

| Geography | |

Paektu Mountain Location in North Korea  Paektu Mountain Paektu Mountain (Jilin) | |

| Location | Ryanggang, North Korea Jilin, China |

| Geology | |

| Mountain type | Stratovolcano |

| Last eruption | 1903[1] |

| Paektu Mountain | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 长白山 | ||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 長白山 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | Ever-white Mountain | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||

| Chosŏn'gŭl | 백두산 | ||||||||

| Hancha | 白頭山 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | Whitehead Mountain | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Manchu name | |||||||||

| Manchu script | ᡤᠣᠯᠮᡳᠨ ᡧᠠᠩᡤᡳᠶᠶᠠᠨ ᠠᠯᡳᠨ | ||||||||

| Romanization | Golmin Šanggiyan Alin | ||||||||

A large crater lake, called Heaven Lake, is in the caldera atop the mountain. The caldera was formed by the VEI 7 "Millennium" or "Tianchi" eruption of 946, which erupted about 100–120 km3 (24–29 cu mi) of tephra. This was one of the largest and most violent eruptions in the last 5,000 years (alongside the Minoan eruption, the Hatepe eruption of Lake Taupo in around AD 180, the 1257 eruption of Mount Samalas near Mount Rinjani and the 1815 eruption of Tambora).

The mountain plays an important mythological and cultural role in the societies and civil religions of both contemporary Korean states. For instance, it is mentioned in both of their national anthems and is depicted on the national emblem of North Korea.

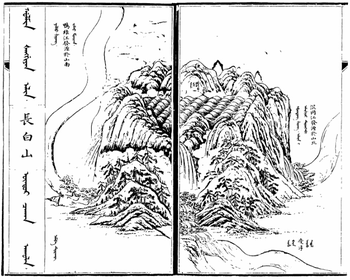

Names

The modern Korean name of the mountain, "Paektusan" or "Baekdusan", was first recorded in the 13th century historical record Goryeosa. It means "white-head mountain". In other records from the same period, the mountain was also called "Taebaeksan", which means "great-white mountain". The modern name of the mountain in Chinese, "Chángbáishān", comes from modern Manchu name of the mountain, which is "Golmin Šanggiyan Alin", which means "ever white mountain". Another Chinese name, "Báitóushān", is the transliteration of "Paektu Mountain".[5] The Mongolian name is "Ondor Tsagaan Aula", which means "lofty white mountain". In English, various authors have used nonstandard transliterations.[6]

Geography and geology

Mount Paektu is a stratovolcano whose cone is truncated by a large caldera, about 5 km (3.1 mi) wide and 850 meters (2,790 ft) deep, partially filled by the waters of Heaven Lake.[1] The lake has a circumference of 12 to 14 kilometers (7.5 to 8.7 mi), with an average depth of 213 meters (699 ft) and maximum depth of 384 meters (1,260 ft). From mid-October to mid-June, the lake is typically covered with ice. In 2011, experts in North and South Korea met to discuss the potential for a significant eruption in the near future,[7] as the volcano explodes to life every 100 years or so, the last time in 1903.[8]

The geological forces forming Mount Paektu remain a mystery. Two leading theories are first a hot spot formation and second an uncharted portion of the Pacific Plate sinking beneath Mount Paektu.[9]

The central section of the mountain rises about 3 mm (0.12 in) per year due to rising levels of magma below the central part of the mountain. Sixteen peaks exceeding 2,500 m (8,200 ft) line the caldera rim surrounding Heaven Lake. The highest peak, called Janggun Peak, is covered in snow about eight months of the year. The slope is relatively gentle until about 1,800 m (5,910 ft).

Water flows north out of the lake, and near the outlet there is a 70-meter (230 ft) waterfall. The mountain is the source of the Songhua, Tumen and Yalu rivers. The Tumen and the Yalu form the northern border between North Korea and Russia and China.

Climate

The weather on the mountain can be very erratic, sometimes severe. The annual average temperature at the peak is −4.9 °C (23.2 °F). During summer, temperatures of about 18 °C (64 °F) or higher can be reached, and during winter temperatures can drop to −48 °C (−54 °F). The lowest record temperature was −51 °C (−60 °F) on 2 January 1997. The average temperature is about −24 °C (−11 °F) in January, and 10 °C (50 °F) in July, remaining below freezing for eight months of the year. The average wind speed is 42 km/h (26 mph), peaking at 63 km/h (39 mph). The relative humidity averages 74%.

Millennium eruption

The mountain's caldera was created in 946 by the colossal (VEI 7)[10] "Millennium" or "Tianchi" eruption, one of the most violent eruptions in the last 5,000 years, comparable to the 180 AD eruption of Lake Taupo and the 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora.[11] The eruption, whose tephra has been found in the southern part of Hokkaidō, Japan, and as far away as Greenland,[12] destroyed much of the volcano's summit, leaving a caldera that today is filled by Heaven Lake.

According to the Book of Koryo History, "thunders from the heaven drum" (likely the explosions from the Millennium eruption) were heard in the city of Kaesong, and then again in the capital of ancient Korea about 450 km (280 mi) south of the volcano, which terrified the emperor so much that convicts were pardoned and set free. According to the book of Heungboksa Temple History, on 3 November of the same year, in the city of Nara (Japan), about 1,100 km (680 mi) southeast from the mountain, an event of "white ash rain" was recorded. Three months later, on 7 February 947, "drum thunders" were heard in the city of Kyoto (Japan), about 1,000 km (620 mi) southeast of Paektu.[11]

Tianwenfeng eruption

The age of the Tianwenfeng eruption is not clear, but the carbonized wood in Heifengkou's lag breccia has been dated at around 4105 ± 90 BP. This eruption formed large areas covered in yellow pumice and ignimbrite[13] and released about 23.14 million tonnes (25.51 million short tons) of SO2 into the stratosphere.[14] The bulk volume of the ejecta is at least 100 km3, making the Tianwenfeng eruption also of VEI 7. The Tianwenfeng eruption has also been recorded in Manchurian myths. Manchus described the mountain as "Fire Dragon", "Fire Demon" or "Heavenly Fire".[15]

Recent events

After these major eruptions, Mount Paektu had at least three smaller eruptions, which occurred in 1668, 1702, and 1903, likely forming the Baguamiao ignimbrite, the Wuhaojie fine pumice, and the Liuhaojie tuff ring.[16]

In 2011, the Government of North Korea invited volcanologists James Hammond of Imperial College, London and Clive Oppenheimer of the University of Cambridge, to study the mountain for recent volcanic activity. Their project was continuing in 2014 and expected to last for another "two or three years".[17][18]

Flora and fauna

There are five known species of plants in the lake on the peak, and some 168 have been counted along its shores. The forest on the Chinese side is ancient and almost unaltered by humans. Birch predominates near the tree line, and pine lower down, mixed with other species. There has been extensive deforestation on the lower slopes on the North Korean side of the mountain.

The area is a known habitat for Siberian tigers, bears, wolves, and wild boars.[19] The Ussuri dholes may have been extirpated from the area. Deer in the mountain forests, which cover the mountain up to about 2,000 meters (6,600 ft), are of the Paekdusan roe deer kind. Many wild birds such as black grouse, owls, and woodpecker are known to inhabit the area. The mountain has been identified by BirdLife International as an Important Bird Area (IBA) because it supports a population of scaly-sided mergansers.[20]

History

The mountain has been worshipped by the surrounding peoples throughout history. Both the Koreans and Manchus consider it sacred, especially the Heaven Lake in its crater.[21]

China

The mountain was first recorded in the Chinese Classic of Mountains and Seas under the name Buxian Shan (Chinese: 不咸山). It is also called Shanshan Daling (Chinese: 單單大嶺) in the Book of the Later Han. In the New Book of Tang, it was called Taibai Shan (Chinese: 太白山).[22] The current Chinese name Changbai Shan was first used in the Liao dynasty (907–1125) of the Khitans[23] and then the Jin dynasty (1115–1234) of the Jurchens.[24] The Jin dynasty bestowed the title "the King Who Makes the Nation Prosperous and Answers with Miracles" (Chinese: 興國靈應王) on the sanshin ("mountain spirit") in 1172 and it was promoted to "the Emperor Who Cleared the Sky with Tremendous Sagehood" (Chinese: 開天宏聖帝) in 1193.

The Manchu clan Aisin Gioro, which founded the Qing dynasty in China, claimed their progenitor Bukūri Yongšon was conceived near Paektu Mountain.

Koreas

The mountain has been considered sacred by Koreans throughout history. According to Korean mythology, it was the birthplace of Dangun, the founder of the first Korean kingdom, Gojoseon (2333–108 BC), whose parents were said to be Hwanung, the Son of Heaven, and Ungnyeo, a bear who had been transformed into a woman.[25] Many subsequent kingdoms of Korea, such as Buyeo, Goguryeo, Balhae, Goryeo and Joseon worshiped the mountain.[26][27]

The Goryeo dynasty (935–1392) first called the mountain Paektu,[28] recording that the Jurchens across the Yalu River were made to live outside of Mount Paektu. The Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910) recorded volcanic eruptions in 1597, 1668, and 1702. In the 15th century, King Sejong the Great strengthened the fortification along the Tumen and Yalu rivers, making the mountain a natural border with the northern peoples.[29] Some Koreans claim that the entire region near Mount Paektu and the Tumen River belongs to Korea and parts of it were illegally given away by Japanese colonialists to China through the Gando Convention.

Dense forest around the mountain provided bases for Korean armed resistance against the Japanese occupation, and later communist guerrillas during the Korean War. Kim Il-sung organized his resistance against the Japanese forces there, and North Korea claims that Kim Jong-il was born there,[30] although records outside of North Korea suggest that he was actually born in the Soviet Union.[31][32]

North Korea uses the mythology of the mountain to promote government projects, such as the Paektusan rocket and the Paektusan computer.[33][34] The peak has been featured on the state emblem of North Korea since 1993, as defined in Article 169 of the Constitution, which describes Mt. Paektu as "the sacred mountain of the revolution".[35] The mountain is often referred to in slogans such as: "Let us accomplish the Korean revolution in the revolutionary spirit of Paektu, the spirit of the blizzards of Paektu!"[36] North Korean media also celebrates natural phenomena witnessed at the mountain as portentous.[37]

It is also mentioned in the national anthems of both Koreas and in the Korean folk song "Arirang".

The standard sidearm for the Korean People's Army is the BeakDuSan pistol (CZ-75) which is named after Mt. Peaktu. [38]

Disputes and agreements

Historical

According to Annals of the Joseon Dynasty, the Yalu and Tumen Rivers were set as the borders in the era of the founder of Joseon Dynasty, Taejo of Joseon (1335–1408).[39] Because of the continuous entry of Korean people into Gando, a region in Manchuria that lay north of the Tumen, Manchu and Korean officials surveyed the area and negotiated a border agreement in 1712. To mark the agreement, they built a monument describing the boundary at a watershed, near the south of the crater lake at the mountain peak. The interpretation of the inscription caused a territorial dispute from the late 19th century to the early 20th century, and is still disputed by academics today. The 1909 Gando Convention between China and Japan, when Korea was under Japanese rule, recognized the area north and east as Chinese territory.

Recent

In 1962, China and North Korea negotiated a border treaty to resolve their undemarcated land border. China received 40% of the crater lake and North Korea kept the remaining land[40], holding approximately 54.5% of the territory and gaining around 230 sq.kms.[41]

Some South Korean groups argue that recent activities conducted on the Chinese side of the border, such as economic development, cultural festivals, infrastructure development, promotion of the tourism industry, attempts at registration as a World Heritage Site, and bids for a Winter Olympic Games, are an attempt to claim the mountain as Chinese territory (Both the People's Republic of China and the Republic of China (Taiwan) claims the region's territory as their own).[42][43] These groups object to China's use of the name Mount Changbai.[24] Some groups also regard the entire mountain as Korean territory that was given away by North Korea in the Korean War.[43]

During the 2007 Asian Winter Games, which were held in Changchun, China, a group of South Korean athletes held up signs during the award ceremony which stated "Mount Paektu is our territory". Chinese sports officials delivered a letter of protest on the grounds that political activities violated the spirit of the Olympics and were banned in the charter of the International Olympic Committee and the Olympic Council of Asia. The head of the Korea Olympic Committee responded by claiming that the incident was accidental and held no political meaning.[44][45][46]

The 2007 official National Atlas of Korea[47] shows the boundary as per the 1962 agreement, roughly splitting the mountain and the caldera lake. South Korea claims the caldera lake and the inside part of the ridge.[48]

Sightseeing

In addition to domestic tourists, most international visitors, including many South Koreans, climb the mountain from the Chinese side, though it is also a popular tourist destination for visitors to North Korea. The Chinese tourism area is classified as a AAAAA scenic area by the China National Tourism Administration.[49]

There are a number of monuments on the North Korean side of the mountain. Paektu Spa is a natural spring and is used for bottled water. Pegae Hill is a camp site of the Korean People's Revolutionary Army 조선인민혁명군 (Korean: 조선인민혁명군) allegedly led by Kim Il-sung during their struggle against Japanese colonial rule. Secret camps are also now open to the public. There are several waterfalls, including the Hyongje Falls which splits into two about a third of the way from the top. In 1992, on the occasion of the 80th birthday of Kim Il-sung, a gigantic sign consisting of metal letters reading "Holy mountain of the revolution" was erected on the side of the mountain. North Koreans claim that there are 216 steps leading to the top of the mountain, symbolizing Kim Jong-il's 16 February birth date, but in reality there are more.[50]

Mount Paektu's location

Mount Paektu's location- Waterfall

- Hot springs

River

River Heaven Lake in winter

Heaven Lake in winter- North slope

See also

References

- "Baekdusan". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- Andy Coghlan (15 April 2016). "Waking supervolcano makes North Korea and West join forces". NewScientist. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- Choe Sang-Hun (26 September 2016). "For South Koreans, a Long Detour to Their Holy Mountain". The New York Times. New York.

- Ehlers, Jürgen; Gibbard, Philip (2004). Quaternary Glaciations: South America, Asia, Africa, Australasia, Antarctica. Elsevier.

The Changbai Mountain is the highest (2570 m a.s.l.) in north-eastern China (42°N, 128°E) on the border between China and Korea.

- ISBN 7-5031-2136-X p. 31

- Examples: Paektu-san ("Paektu-san: North Korea". Retrieved 4 October 2010.) (Korean 백두산("백두산: North Korea". Retrieved 4 October 2010.)), Ch'ang Pai ("Ch'ang Pai: China". Retrieved 4 October 2010.), Chang-pai Shan,("Chang-pai Shan: China". Retrieved 4 October 2010.), Chōhaku-san ("Chōhaku-san: China". Retrieved 4 October 2010.), Hakutō ("Hakutō: China". Retrieved 4 October 2010.), Hakutō-san("Hakutō-san: China". Retrieved 4 October 2010.), Hakutō-zan ("Hakutō-zan: China". Retrieved 4 October 2010.), Paik-to-san ("Paik-to-san: China". Retrieved 4 October 2010.), Mount Paitoushar ("Mount Paitoushar: China". Retrieved 4 October 2010.), Paitow Shan ("Paitow Shan: China". Retrieved 4 October 2010.), Pei-schan ("Pei-schan: China". Retrieved 4 October 2010.), and Bai Yun Feng.

- Sam Kim, Yonhap (22 March 2011). "S. Korea agrees to talks on possible volcano in N. Korea". Yonhap News Agency. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- "Vigil at North Korea's Mount Doom". Science Magazine. Retrieved 16 December 2012.

- "NERC - Science without borders".

- "Changbaishan". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- Pan, Bo; Xu, Jiandong (2013). "Climatic impact of the Millennium eruption of Changbaishan volcano in China: New insights from high-precision radiocarbon wiggle-match dating" (PDF). Geophysical Research Letters. 40 (1): 54–59. Bibcode:2013GeoRL..40...54X. doi:10.1029/2012GL054246.

- Sigl, M (2015). "Timing and climate forcing of volcanic eruptions for the past 2,500 years". Nature. 523 (7562): 543–49. Bibcode:2015Natur.523..543S. doi:10.1038/nature14565. PMID 26153860.

- 刘, 若新 (1998). 长白山天池火山近代喷发 (in Chinese). 科学出版社. ISBN 9787030062857.

- Zhengfu, Guo (2002). "The mass estimation of volatile emission during 1199–1200 AD eruption of Baitoushan volcano and its significance". Science in China Series D: Earth Sciences. 45 (6): 530. doi:10.1360/02yd9055.

- Wei, Haiquan (2001). "Chinese Myths and Legends for Tianchi Volcano Eruption". Acta Petrologica et Mineralogica.

- Wei, Haiquan (2013). "Review of eruptive activity at Millennium volcano, Paektusan, northeast China: implications for possible future eruptions". Bull Volcanol. 75 (4). Bibcode:2013BVol...75..706W. doi:10.1007/s00445-013-0706-5.

- "Rumbling volcano sees N. Korea warm to the West". CBS News. 16 September 2014.

- Hammond, James (9 February 2016). "Understanding Volcanoes in Isolated Locations". Science & Diplomacy. 5 (1).

- Gomà Pinilla, D. (2004). Border Disputes between China and North Korea. China Perspectives 2004(52): 1−9.

- "Mount Paekdu". Important Bird Areas factsheet. BirdLife International. 2013. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

- Fravel, M. Taylor (2008). Strong Borders, Secure Nation: Cooperation and Conflict in China's Territorial Disputes. Princeton University Press. pp. 321–2. ISBN 978-1-4008-2887-6.

- Second Canonical Book of the Tang Dynasty. 《新唐書.北狄渤海傳》:"契丹盡忠殺營州都督趙翽反,有舍利乞乞仲象者,與靺鞨酋乞四比羽及高麗餘種東走,度遼水,保太白山之東北,阻奧婁河,樹壁自固。" (English translation: Khitan general Jinzhong Li killed Hui Zhao, the commanding officer of Yin Zhou. Officer Dae Jung-sang, with Mohe chieftain Qisi Piyu and Goguryeo remnants, escaped to the east, crossed Liao River, guarded the northeast part of the Grand Old White Mountain, blocked Oulou River, built walls to protect themselves.)

- "Records of Khitan Empire". 《契丹國志》:"長白山在冷山東南千餘里......禽獸皆白。"(English translation: "Changbai Mountain is a thousand miles to the southeast of Cold Mountain...Birds and animals there are all white.")

- "Canonical History Records of the Jurchen Jin Dynasty". 《金史.卷第三十五》:"長白山在興王之地,禮合尊崇,議封爵,建廟宇。""厥惟長白,載我金德,仰止其高,實惟我舊邦之鎮。" (English translation: "Changbai Mountain is in old Jurchen land, highly respectful, suitable for building temples. Only the Changbai Mountain can carry Jurchen Jin Dynasty's spirit; It is so high; It is a part of our old land.")

- Cumings, Bruce (2005). Korea's Place in the Sun: A Modern History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 22–25. ISBN 978-0-393-32702-1.

- "Korea Britannica" (in Korean). Enc.daum.net. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- Song, Yong-deok (2007). "The recognition of mountain Baekdu in the Koryo dynasty and early times of the Joseon dynasty". History and Reality V.64.

- Goryeosa (King Gwangjong reign, 959)

- "Yahoo Korea Encyclopedia". Yahoo!. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- "Moved". Korea-dpr.com. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- Sheets, Lawrence (12 February 2004). "A Visit to Kim Jong Il's Russian Birthplace". NPR.

- "Profile: Kim Jong-il". BBC News. 16 January 2009.

- Cumings, Bruce (2005). Korea's Place in the Sun: A Modern History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 28, 435. ISBN 978-0-393-32702-1.

- Jager, Sheila Miyoshi (2013). Brothers at War – The Unending Conflict in Korea. London: Profile Books. pp. 464–65. ISBN 978-1-84668-067-0.

- Socialist Constitution of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (PDF). Amended and supplemented on April 1, Juche 102 (2013), at the Seventh Session of the Twelfth Supreme People's Assembly. Pyongyang: Foreign Languages Publishing House. 2014. p. 35. ISBN 978-9946-0-1099-1.CS1 maint: others (link)

- "Decoding North Korea's fish and mushroom slogans". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- "Wonders of nature". Korean Central News Agency. 12 July 1997. Archived from the original on 12 October 2014.

- https://www.dailynk.com/english/mt-paektu-handgun-gifted-by-former-supreme-leader-vanishes/

- (in Korean and Chinese) 朝鮮王朝実録太祖8卷4年(1395年)12月14日 "以鴨綠江爲界。""以豆滿江爲界。"

- Fravel, M. Taylor (1 October 2005). "Regime Insecurity and International Cooperation: Explaining China's Compromises in Territorial Disputes". International Security. 30 (2): 46–83. doi:10.1162/016228805775124534. ISSN 0162-2889.

- 역사비평 (Historical Criticism), Fall 1992

- Chosun Archived 17 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- Donga.

- "China Upset with 'Baekdu Mountain' Skaters". Chosunilbo. Archived from the original on 29 March 2007. Retrieved 15 March 2007.

'There are no territorial disputes between China and South Korea. What the Koreans did this time hurt the feelings of the Chinese people and violated the spirit of the Olympic Charter and the Olympic Council of Asia,' the official said, according to the China News.

- The Korea Times, "Seoul Cautious Over Rift With China". Retrieved 2 February 2007

- "Sports World Korea". Yahoo! News. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- National Geographic Information Institute, Ministry of Construction and Transportation, The National Atlas of Korea, Gyeonggi-do, (South) Korea, 2007, p. 14, http://www.ngii.go.kr

- 네이버 뉴스 라이브러리 (in Korean). Newslibrary.naver.com. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- "AAAAA Scenic Areas". China National Tourism Administration. 16 November 2008. Archived from the original on 4 April 2014. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- Bärtås, Magnus; Ekman, Fredrik (2014). Hirviöidenkin on kuoltava: Ryhmämatka Pohjois-Koreaan [All Monsters Must Die: An Excursion to North Korea] (in Finnish). Translated by Eskelinen, Heikki. Helsinki: Tammi. pp. 82–86. ISBN 978-951-31-7727-0.

Further reading

- Hetland, E.A.; et al. (2004). "Crustal structure in the Changbaishan volcanic area, China, determined by modeling receiver functions". Tectonophysics. 386 (3–4): 157–75. Bibcode:2004Tectp.386..157H. doi:10.1016/j.tecto.2004.06.001.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Baekdu Mountain. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Baekdu Mountains. |

| Chinese Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Chinese Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Chinese Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Chinese Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- "Changbaishan". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- Virtual Tour: 360 degree interactive panorama of Mount Paektu (DPRK 360, September 2014)

- The Scenery of Mt. Paektu at Naenara

- A slide show about Paektusan (in German)