Italian irredentism in Switzerland

Italian irredentism in Switzerland was a political movement that promoted the unification to Italy of the Italian-speaking areas of Switzerland during the Risorgimento.

History

In the early 19th century the ideals of unification in a single Nation of all the territories populated by Italian speaking people created the Italian irredentism.

In southern Switzerland those ideals were minimally followed until the creation of the Kingdom of Italy in 1861 and up to World War I.

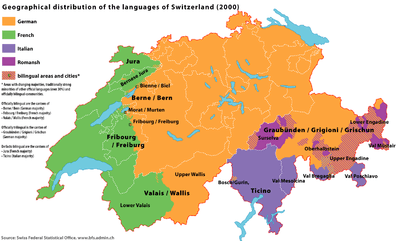

Following the rise to power of Italian Fascism, however, the initial moderate irredentism started to change to one full of aggression: the same Benito Mussolini created in the early 1930s the Partito Fascista Ticinese (Ticino Fascist Party).[1] The main ideal of this party was to bring the Italian frontier up to the Gottardo Pass (Catena mediana delle Alpi [2]) in the Alps through political unrest and possible referendums (supported, in case of need, by the Italian Army).[3]

In 1934 was done a small tentative by the Ticino fascists: the March on Bellinzona", similar to the March on Rome. But it was successfully contrasted by socialist organizations, like "Liberi e Svizzeri" of Guglielmo Canevascini, promoted even by the Swiss government.[4]

Successively, in the 1935 elections the fascists obtained just 2% of the votes and since then their movement faded away to less than 100 members.[5]

Before World War II the Italian irredentism in Switzerland was reduced to have followers mainly between the descendants of Italians emigrated to Ticino at the end of the 19th century, but was ruled and promoted by a small group of ticino intellectuals with their active newspapers and propaganda.

The most important of these intellectuals was Teresina Bontempi, who created the magazine L'Adula. She denounced in her writings, together with Rosetta Colombi, the germanization of Canton Ticino promoted by the Swiss government.[6] Indeed, the German-speaking population in Canton Ticino went from 2.6% in 1837 to 5.34% in 1920 and nearly 10% in 1940.

As a consequence of this political activity she was involved in continuous problems with the Swiss government, that finally jailed her in 1936.[7] She was forced to move to Italy as a political refugee after some months.

The most renowned fascist born in Canton Ticino was Aurelio Garobbio, who tried to imitate Gabriele D'Annunzio with his organization called Giovani Ticinesi.[8] After 1935 Garobbio was the main responsible of the Italian irredentism in Switzerland and was with Mussolini until his death in spring 1945, when tried to organize a last fascist area of defense in Valtellina next to Ticino.[9]

See also

- Italia irredenta

- Italian immigration to Switzerland

- Risorgimento

- Swiss Italians

- Teresina Bontempi

Notes

- Fra Roma e Berna, di Mauro Cerutti (in Italian) Archived 2011-08-30 at the Wayback Machine

- Map of "Catena mediana delle Alpi" as possible northern Italian border in Switzerland

- rossi, Contechnet.it massimo. "Italia-Svizzera: la storia dal 1861 al 2011". Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- M. Cerutti, Fra Roma e Berna. La Svizzera italiana nel ventennio fascista, p. 465.

- "Il cattolicesimo ticinese e i fascismi: la Chiesa e il partito conservatore ticinese nel periodo tra le due guerre mondiali". Saint-Paul. 1 January 1999. Retrieved 12 January 2017 – via Google Books.

- "Il sogno irredentista del Ticino (in Italian)". Archived from the original on 2016-03-10. Retrieved 2015-01-12.

- Ilse Shneiderfranken.Le industrie del Canton Ticino. Belinzona, 1937

- Garobbio, Aurelio. Gabriele D'Annunzio e i «Giovani Ticinesi»: le vicende de «L'Adula» p. 45

- Rocco, Giuseppe (1 January 1992). "Com'era rossa la mia valle: una storia di antiresistenza in Valtellina". GRECO & GRECO Editori. Retrieved 12 January 2017 – via Google Books.

Bibliography

- Cerutti, Mauro. Fra Roma e Berna. La Svizzera nel ventennio fascista. Edizioni Franco Angeli. Milano, 1986.

- Crespi, Ferdinando. Ticino irredento. La frontiera contesa. Dalla battaglia culturale dell'"Adula" ai piani d'invasione. Edizioni Franco Angeli. Milano, 2004.

- Dosi, Davide. ll cattolicesimo ticinese e i fascismi: la Chiesa e il partito conservatore ticinese nel periodo tra le due guerre mondiali. Editore Saint-Paul. Lugano, 1999 ISBN 2827108569

- Garobbio, Aurelio. Gabriele D'Annunzio e i «Giovani Ticinesi»: le vicende de «L'Adula», Editore Centro Studi Atesini. Trento, 1988.

- Lurati, Ottavio. Dialetto e italiano regionale nella Svizzera italiana. Lugano, 1976.

- Schneiderfranken, Ilse. Le industrie del Canton Ticino. Bellinzona, 1937.

- sulle quattro valli italofone (Mesolcina, Calanca, di Poschiavo, Bregaglia) e su Bivio, Vignoli, Giulio, I territori italofoni non appartenenti alla Repubblica Italiana agraristica. Giuffrè, Milano, 1995.