Jämtland

Jämtland (Swedish: [ˈjɛ̌mːtland] (![]()

Jämtland Jamtlann | |

|---|---|

Coat of arms | |

| |

| Coordinates: 63°00′N 14°40′E | |

| Country | |

| Land | Norrland |

| Counties | Jämtland County Västernorrland County Västerbotten County |

| Area | |

| • Total | 34,009 km2 (13,131 sq mi) |

| Population (2016)[1] | |

| • Total | 115,331 |

| • Density | 3.4/km2 (8.8/sq mi) |

| Ethnicity | |

| • Language | Swedish |

| • Dialect | Jamtlandic |

| Culture | |

| • Flower | Orchid |

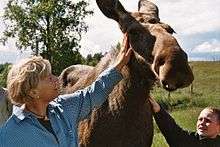

| • Animal | Moose |

| • Bird | Hawk owl |

| • Fish | Brown trout |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

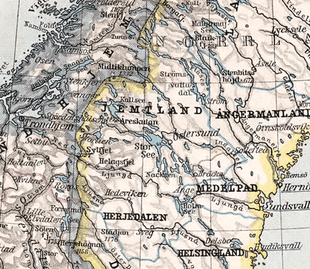

Jämtland was originally an autonomous peasant republic,[2] its own nation[2] with its own law, currency[3] and parliament. Jämtland was conquered by Norway in 1178 and stayed Norwegian for over 450 years until it was ceded to Sweden in 1645. The province has since been Swedish for roughly 370 years, though the population did not gain Swedish citizenship until 1699. The province's identity is manifested with the concept of a republic within the kingdom of Sweden, although this is only done semi-seriously.[4]

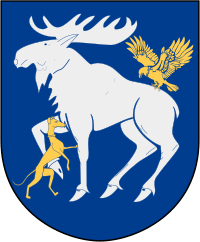

Historically, socially and politically Jämtland has been a special territory between Norway and Sweden. This in itself is symbolized in the province's coat of arms where Jämtland, the silver moose, is threatened from the east and from the west. During the unrest period in Jämtland's history (1563–1677) it shifted alignment between the two states no less than 13 times.[5]

Etymology

Jämtland's name derives from its inhabitants, the Jamts.[6] The name can be traced back to Europe's northernmost runestone, the Frösö Runestone from the 11th century, where it is found as eotalont (normalized Old Norse: Jamtaland). The root of Jamt (Old West Norse: jamti), and thus Jämtland, derives from the Proto-Germanic word stem emat- meaning persistent, efficient, enduring and hardworking.[6] The Proto-Norse prefix eota (jamta) is a genitive plural case.

It is not known how the Jamts got their name. One possible explanation is presented in the Icelandic work Heimskringla from the 13th century. In the Saga of Håkon Góði, Snorri Sturluson narrates about Kettil Jamti, a son of Anund Jarl from Sparbu in Trøndelag who fled from Norway when Harald Fairhair united the country with brute force in the 9th century. His descendants then came to bear his name. An alternative explanation comes from the excessive iron production that took place in the province before the Viking Age. A folk etymological theory is that the name ought to have something to do with the "even" (as in level or flat) parts around the lake Storsjön. This theory is based on the similarity between the Swedish words jämt (from emat-) and jämnt (from Germanic *ebna, "even").[6]

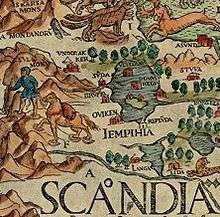

The name Jämtland with an Ä is a 20th-century Swedish alteration of the older spelling Jemtland. Localities settled by Jamtish emigrants such as Jemtland in Ringsaker, Norway and Jemtland in Maine, United States were founded before the alteration occurred. In the nearby Norwegian province of Trøndelag old settlements such as Jamtøya, Jamtgarden and Jamtåsen all use the prefix Jamt-, just like the regional name, however the Trøndersk name for Jämtland is Jamtlainn,[7] whilst the Jamtish name is Jamtland. As the d is silent the form Jamtlann is also common. The most genuine Jamtish pronunciation of the name is however the now uncommon form Jamplann [ˈjampˌlanː], deriving from older names such as Jamptaland, found in ancient documents. The regional name Jamtland has only status as an official form in Nynorsk[7] and Icelandic,[8] but is popularly used among locals which is one of the reasons as to why the regional museum was given the dialectal name Jamtli (Swedish jämtsk backsluttning),[9] "Jamtish hillside".

History

Prehistory

Some finds from the time before humans have been discovered in Jämtland, most notably the remains from a woolly mammoth in Pilgrimstad.

The first humans came to Jämtland from the west across the Keel approximately 7000-6000 BC, after the last ice age. The climate was at the time much warmer than today and trees such as oak were growing at the top of today's mountains. Several thousand archaeological remains have been located in the province, predominantly near old camp-sites, beaches and lakes. The oldest settlement found is located at Foskvattnet, not far way from the so-called Fosna culture, this settlement has been dated to 6600 BC. In Jämtland the moose was the dominant prey, which is clearly shown on petroglyphs and rock paintings in for example Gärde and Glösa. Jämtland has over 20,000 documented ancient monuments, the oldest one being an arrowhead found in Åflo near Kaxås in Offerdal parish possibly older than 8,000 years, which would make it one of the oldest Stone Age finds in all of Sweden.

Rock paintings found in Jämtland often collocates with various trapping pits and well over 10,000 pits used for hunting have been located, which is much more than any other Scandinavian region. Trapping or hunting pits were placed in areas in close proximity of the hunted animal in question, usually in known places where the animals moved. Because of this there are several places where pits have been dug separately in lines stretching on for miles throughout the landscape. Several place names in Jämtland still display the significance these pits had to the tribes.

|

|||

| Trapping pit | A moose painted with red ochre near Fångsjön | Fångsjön rock art site, dated to 2500-2000 BC | Burned rocks in northern Jämtland |

A Jamtish Neolithic culture emerged during late Roman Iron Age in Storsjöbygden, although the hunter-gatherers had come in contact with this lifestyle long before they settled down themselves. Since the hunts were rich and successful in Jämtland, it took a long time before a change occurred.

The Neolithic revolution happened quickly once initiated since the Trønders had been farmers for a long time and some of the Jamts had already begun herding. The Jamtish farmers grew first and foremost barley, although palynological study also show hemp. At the end of the 4th century a fortress, Mjälleborgen, was established on Frösön to control the iron production and trade that took place. At the same time Kurgans start appearing in the Jamtish landscape, just like in Bertnem in Trøndelag and Högom in Medelpad. The western influence from Trøndelag through Jämtland to Norrland was at the time extensive.

The expansion of settlement was somewhat halted in the 7th century and Mjälleborgen was abandoned in the 8th century. A human migration occurred at the same time and the people concentrated themselves around Storsjön with villages such as Frösön, Brunflo, Rödön, Hackås, Lockne and Näs being larger communities. Storsjöbygden became an oasis in the middle of the Scandinavian inland, surrounded by dense forest. Horses were the only reliable means of transportation and therefore a necessity.

During the Viking Age, the settlement in the province grew. This confirms the sagas written by Snorri Sturluson, where he narrates about the Vikings who fled from Harald Fairhair and Norway and took residence in Jämtland, just like many Norwegians at the same time fled and colonized Iceland. When a climate change (which later resulted in the Medieval Warm Period) took place, Frösön acquired the position as regional centre. The warmer climate made the agriculture flourish, the stock-raising and the special inland Scandinavian herding or "livestock drifting", buföring, was developed further. This is especially true for the southern parts of Jämtland when the so-called "fell cow" was introduced. The hunt for moose and other wild animals increased during this period. Religiously the Jamts had abandoned the indigenous Germanic tribal religion in favour of the Christian faith. In religious practice, Jämtland was dominated by the older Vanir gods (Freyr, Njord, Ullr etc.), although the Æsirs were also worshiped.

As the population continued to grow, the Jamts established a Thing (assembly), just like other Germanic tribes. Jamtamót came into existence shortly after the world's oldest parliament, the Icelandic Althing, was instituted in 930 CE. Jamtamót is unique in Scandinavia since it is the only one referred to as mót instead of þing, although they have the same meaning.

Medieval period

Jämtland was Christianized in the middle of the 11th century when the Frösö Runestone appeared (the only one in the world that tells about the christening of a country), shortly after Olaf II of Norway died in the Battle of Stiklestad just west of Jämtland. During this period Jämtland turned into a Christian region and the first church, Västerhus chapel was built shortly after the runestone appeared.

According to Snorri Sturluson's Sagas the Jamts sometimes paid taxes to Norwegian kings such as Håkon Adalsteinsfostre and Øystein Magnusson for protection. The Sagas also mentions that the Jamts at one occasion also paid taxes to a king in Svealand. The Sagas reliability on the matter has been defined as low.[11] In the oldest written source for Norway, Historia Norwegiæ, it is however clearly stated that Norway borders in the north-east to Jämtland.

During the civil war era in Norway Jämtland was defeated by king Sverre of Norway after losing the Battle of Storsjön. This was the last war fought by the Jamts under their own elected leaders. The consequences of this defeat was less autonomy. Jämtland never became a fully integrated part of Norway and had the same status in the Kingdom of Norway (872–1397) as the Atlantic isles like Shetland and Orkney, even though Jämtland was connected by land with the rest of Norway. This is clearly shown when Haakon V of Norway refers to Jämtland as his "eastern realm — öystræ rikinu".

Turbulent times

After Norway was forced into a personal union with Denmark (Denmark-Norway) in 1536 Jämtland came to be governed from Copenhagen. When the reformation (Catholicism survived in some places into the 17th century) was forced upon the population when the kings took control of the church. Sweden's separation from the Kalmar Union transferred Jämtland from a central Scandinavian region into a border region between two aggressive states. This eventually led to conflict, first in 1563 during the Nordic Seven Years' War (after which Jämtland was put under the diocese of Nidaros), then in 1611 during the Kalmar War. Conflict continued and Jämtland was occupied yet again in 1644 during the Hannibal War by Swedish forces under the command of Henrik Fleming. The Swedish troops were however quickly driven out by Norwegians and locals. Sweden did however win that war in the south and received Jämtland as a part of the Treaty of Brömsebro in 1645.

After this Denmark-Norway tried to regain the province, first in 1657 (Dano-Swedish war of 1657) where the Norwegians were hailed as liberators. Then for a longer period in 1677 with the conquest of Jemtland. The Jamts conducted snapphane (guerilla) warfare against the Swedish army and during this time a Jamt from Lockne, the first known Jamtish poet, wrote a scurrilous song that was sung throughout the province during the war. It involved the Swedish governor of Jämtland and he had the song translated into Swedish from Jamtish and sent to the king. The last segment of the song was the most derisive one (direct English translation to the right):

|

We have now lived for 30 years time |

The conquest failed and once Jämtland was in Swedish hands a Swedification process began. The Diocese of Härnösand was instituted at the Swedish coast. Schools were established (to direct the Jamts away from Trondheim). The population did not receive Swedish citizenship until 1699. Thus the Jamts were the last people from an acquired territory in Sweden to become Swedish.

The Jamtish people maintained some self-governance. The Jamtamót had been transformed into a Danish landsting in the early 16th century. Even though it was banned in the end of the same century, it continued to be held in secret. After the transition to Sweden some parts were transmitted into a Swedish landsjämnadsting.

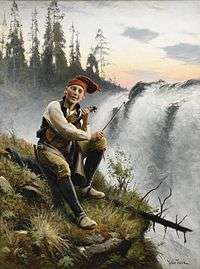

Sweden's intentions in the province were first and foremost focused on defense, which led to a burden on the Jamtish farmers. The Jamts managed to enforce a treaty in 1688 which stated that Jamts were under no circumstances obligated to defend anything but their own province. This treaty was eventually broken by king Charles XII and Jamts participated in Carl Gustaf Armfeldt's Norwegian campaign during the Great Northern War. The campaign was unsuccessful and when Charles XII died in southern Norway Armfeldt marched back to Jämtland. On New Year's Eve 1718 a massive blizzard arose and over 3,000 Caroleans succumbed in Jämtland's mountains mostly due to poor clothing. The time that followed "the Age of Liberty" brought changes to the province's agriculture, with significances such as the potato and better granaries through national politics. The standard of living was greatly improved during this period. However, the visions and ideas behind the improvements also led to one of the greatest environmental disasters in Scandinavia when the lake Ragundasjön was drained and the great rapid Gedungsen cut off, creating the so-called "dead waterfall". It was the result of a project that sought to circumvent the obstacle posed by the waterfall for timber transportation on Indalsälven.

Modern period

In order to end the free trade conducted by "faring-men" or "faring-farmers" (fælmännan or fælbönnran in dialect) Jämtland's first and only city, Östersund, was founded by Gustaf III 1786, though plans had existed since the province was seceded. It took almost one hundred years after this before the province began industrializing when the rail road Mittbanan-Meråkerbanen was established between Sundsvall, Östersund and Trondheim. This evolved the logging process and also led to more people migrating to Jämtland, not to mention all the tourists who came for the "fresh air". As a side effect the rail road also meant the end of the faring traditions. After the unsuccessful (or successful, depending on the viewer) channelling of Gedungsen Jämtland's rich forests could be used in sawmills along the coast. A great deal of the forest was sold to large corporations since for the first time in history the farmers could earn money from their forests.

In the late 19th century the province was struck by social movements. In Jämtland the "free minded" Good Templar movement (a part of the temperance movement) came to dominate completely, in fact, the movement drew its strongest support (in relation to the population) in Jämtland in the entire world, and it was also here, in Östersund, that the world's largest order house was built. Jämtland failed to industrialize, mostly due to the residents opposition to industries, which were seen as the destroyers of society. Keeping Jämtland as a clean environment, but also making it a region of raw material extraction. Due to the rail road the city of Östersund quickly grew with settlers arriving from the countryside and southern Sweden, giving it the true character of a city, rather than a mere village with city status. The rise of Östersund brought a more excessive trade than before, handicrafts etc. Just like in the rest of the Western world a modernisation process started in the 20th century. New items such as cars, fridges, television etc. made their way into people's lives.

With the establishment of the socialist Folkhemmet (the people's home) and the Rehn-Meidner model Jämtland became a true neglected area in Sweden. The model deemed it necessary to concentrate the Swedish population in cities, at the coast and in the south. Jämtland an inland region in Norrland with the largest part of the population living in the countryside in Sweden was by far the most unprofitable region one could imagine. When the politics were launched Jämtland experienced the largest population loss in modern Swedish history. Local companies were forced into bankruptcy and unemployed people were encouraged to move to cities at the coast or in the south through subsidies and governmental commercials. At the same time taxes were rising and the public sector growing. Opposition to the loss of population and the centralist plans among officials regarding Jämtland County led to the creation of the Republic of Jamtland (see below).

Subdivision and law

Jämtland was originally divided into four parts, so called farthings (fjalingan or fjålingan in Jamtish), just like Iceland (fjórðungr in Icelandic). This division is similar to the hundred subdivision the rest of Scandinavia had. Just like on Iceland these farthings were named after cardinal directions. Exactly how the borders for each farthing went is unknown although it has been suggested that they all reached Storsjön in the center of the province. The eastern farthing at Brunflo, the western from Trångsviken to the Rödö peninsula and the south farthing from Oviken and Hackås and southwards. The northern farthing is assumed to have covered all the northern parts in addition to all the islands in Storsjön (like Frösön, Norderön, Andersön etc.) and Mörsil plus Hallen parish all the way to Oviksfjällen.

The farthings were lesser administrative regions, more or less juridical districts with their own assemblies, all parallel with the common assembly on Frösön. The old law used in Jämtland is the so-called Jamtish Law, referred to in old documents as e.g. Jamptskum laughom. Old documents also makes reference to a specific law book — Jamskre loghbok.[12] The law book has never been recovered and it is assumed to have been destroyed in the 16th century, or never having existed at all. Nevertheless, the Jamtish law was either the same, or strongly influenced by the Frostating law applied on Trøndelag.

When Magnus the law-mender became the king of Norway he instituted a national law for Norway in 1276, however Jämtland was not applied by this law. Jämtland came under this law either in 1365 or in the middle of the 16th century.[13] The divisions by farthings were replaced in the 16th century by Court Districts, shortly after Jämtland got its own Norwegian law thing.

- Court Districts in Jämtland

- Berg Court District

- Brunflo Court District

- Hackås Court District

- Hallen Court District

- Hammerdal Court District

- Lits Court District

- Offerdal Court District

- Oviken Court District

- Ragunda Court District

- Revsund Court District

- Rödön Court District

- Sunne Court District

- Undersåker Court District

There is also an historical subdivision of Jämtland in Jamtlandic. One area is referred to as Nol i bygdom "the north countryside" and consist of Lit-Hammerdal and the area further north. Sö i bygdom "the south countryside" or Sunna sjön consists of the area just south of Storsjön; Oviken, Berg, Sunne and Hallen. Öst i bygdom (also ast, äst, ust, åst etc. instead of "öst") for eastern Jämtland, mainly Ragunda, Revsund and Brunflo. Opp i lännan "up in the lands" refers to western Jämtland, Undersåker and Offerdal. Fram på lännan "the front", "central lands" or in på lännan "in on the lands" consists of the area around Storsjön like Frösön, Rödön etc. A person from this area is called a framlänning "front lander".

Churches

After the conversion to Christianity several parishes (so called socknar, related to "seek") were established in Jämtland, these are now replaced by over 40 församlingar, meaning "assemblage". These are organized by so-called kontrakt "contracts", collaboration units within the Swedish church's each diocese. Jämtland is a part of the Härnösand diocese, established two years after Jämtland was ceded to Sweden. In Jämtland there are five contracts; Bräcke-Ragunda, Krokom-Åre, Strömsund and Östersund's contract, along with Berg-Härjedalen. Although only half of the parishes in the last one are actually located in Jämtland, the rest are located in Härjedalen.

When the first churches were established in Jämtland during the medieval period they were done so by a small number of farmers. Estimations show that there were seldom more than 30 to 40 farmers in each parish. In some cases, like in Kyrkås, Marby and Norderö parish the farmers were probably 20 or less. These original parishioners built churches that's lasted for centuries, many are still existing and functioning today. This is quite remarkable given that they built these churches in stones, much larger than their ordinary timber houses and in a material the parishioners were not accustomed to (given that they only used timber). The churches became a matter of concern for every parishioner, the centre in each parish. Everybody had to help build them and their descendants had to maintain them, this carried on for generations. Families have decorated the churches throughout history with various ornaments and art such as valuable inventories, wood carvings, paintings (predominantly biblical illustrations), textiles, silver and tin along with various handicrafts. Almost the entire older popular culture in Jämtland is tied to the churches. Making them the core of Jämtland's cultural heritage.[14]

The churches have symbolized a connection between Jämtland's population through generations and this is still the case for many today. People are joined together through cheerful moments such as christening, Holy Matrimony, confirmation, through crisis and mournful times like funerals. In Jämtland-Härjedalen the free church movement did not become near as widespread as in the rest of Sweden. Because of this Jämtland and Härjedalen have a large number of members in the Swedish church since nine out of ten in fact are members. Although nowadays church attendance is much lower, back then every parishioner gathered on the Sabbath because no one was allowed to work. Within each parish distinctive customs, bunads and dialects developed because of this, especially the dialects are known to differ from parish to parish in Jämtland.

Jämtland also had a great deal of equality between each parishioner, Jämtland lacked a nobility and there are no noble family coats of arms nor authorial marks in the churches, which is very common in the rest of Sweden. Jämtland also lacked a specific "bench order" (an order based on rank that defined where you were allowed to sit in the church), something that other churches had. In Jämtland the principle "among farmers no other rank except age and life-time"[15] applied.

Each parish also had an assembly, where every parishioner was present and decisions were only taken unanimously. If they were not able to come to a mutual understanding the matter had to rest and be resumed later until everybody agreed. In the community houses the village's prominent people, so called byalag, gathered to decide on mutual concerns such as split-rail fences, ditch construction and agricultural related stuff. The central figure in each district was the priest. He dealt with most matters since he was in contact with every parishioner. He meddled in conflicts and gave advice and comfort in various situations. Besides preaching and informing the priest was also a farmer himself, often a forerunner in the field. The priest did not always go the authority's errand, sometimes he tried to help his fellow parishioners fend off extra taxes and military services.[16]

Gallery

The medieval fortification next to Brunflo's church

The medieval fortification next to Brunflo's church Bodda Prayerhouse

Bodda Prayerhouse Interior from the old church of Marby

Interior from the old church of Marby Old church of Åsarne

Old church of Åsarne

The large church in Östersund

The large church in Östersund Revsund church with service visitor's stables

Revsund church with service visitor's stables Church of Hackås

Church of Hackås Old church of Ragunda

Old church of Ragunda Kolåsen Sami Chapel

Kolåsen Sami Chapel Church of Häggenås

Church of Häggenås Church of Kall

Church of Kall

Sami people

In Jämtland there are also Sami people. The Sami in Jämtland are Southern Sami people and speak Southern Sami (or åarjelsaemien giele, as it is known in Southern Sami), a language mutually unintelligible with the other Sami languages. The Sami in Jämtland have historically been referred to as "Lapps" and sometimes by using the vague word "Finns" (supposedly related to English "find", see Fenni), though they prefer to call themselves Sami. There have been Sami peoples in Jämtland from pre-historic times; exactly how many, however, is disputed.[17] The northernmost part of Jämtland, Frostviken, is originally a Sami area, historically referred to as a Finnmark. However, the ancestors to the Sami people who live south of this area today probably did not come to the area before the 16th century,[18] when large-scale reindeer herding began, leading to a nomadic lifestyle among the Sami people. This also led to several conflicts in court between Sami people in Jämtland and the land owners. At the dawn of the 20th century, the Swedish state had an official policy which stated that "Lapp should be Lapp" and that they should all live a "traditional" Sami life and not integrate in the society. This has now changed and only a minority are in fact reindeer-herders. The Sami people in Jämtland are closely connected to their brethren living in Trøndelag, and a distinctive feature of the Southern Sami culture is the yoik called vuoille.

Heraldry

The arms are represented with a ducal coronet. Blazon:

- I blått fält en gående älg av silver med en lyftande falk på ryggen och i posten åtföljd av en vänstervänd, upprest hund, båda av guld.[19][20]

English translation:

- "In a blue field, a walking moose of silver [with red antlers] with a striking falcon on its back accompanied by a reared hound in front, both of gold."

The coat of arms of Jämtland, created for Karl X Gustav's funeral, derived from a seal which had been granted to Jämtland in 1635 by the Danish king.[19] The beasts on this seal were difficult to identify. (Is the primary animal a deer, moose or reindeer? Is it a dog, wolf or bear? An eagle or a falcon?) The identity of these animals as a moose between a dog and a falcon was settled in 1884. According to popular perception, these represent Jämtland torn between Norway and Sweden, though obviously this meaning was not officially assigned by any royal authority.[19] Svante Höglin claimed the scene to portray a moose hunted by a trained hunting dog and falcon, and in 1935 the coat of arms was revised, adding a collar and a bell to aid in identifying the dog and the falcon, respectively.[19] Strangely, the revised blazon does not mention the moose's attire although the prototype in the Riksheraldikerämbetet (Swedish National Heraldry Office) is provided with secondary colours for the antlers, beak, hooves and claws.[19]

Jämtland's first seal was the one depicted above from the medieval period. It was abolished after the Nordic Seven Years' War and the second seal of Jämtland was used between 1575-1614. This seal contained two Olav-axes and was also abolished after a Swedish occupation, the one during the Kalmar War. When Jämtland became Swedish it was not suitable to use one of the older seals with such a strong Norwegian influence as a basis for a new Swedish coat of arms. So the latest seal was used instead, even though it was in fact of Danish origin.

Arms of the Jämtland Air Force Wing

Arms of the Jämtland Air Force Wing Arms of Jämtland County

Arms of Jämtland County

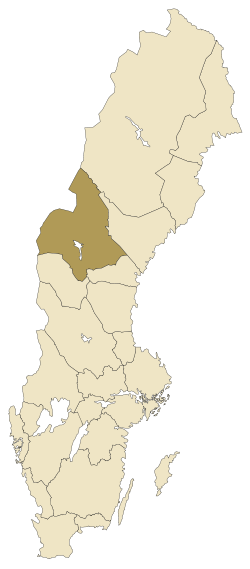

Current administration

Just like every other historical province of Sweden Jämtland serves no administrative purposes, but serves as an historical, geographical and cultural region. Jämtland makes up three quarters of the Swedish administrative province Jämtland County, though a small uninhabited part in northern Jämtland is a part of Västerbotten County and the area around Överturingen is a part of Västernorrland County. The landsting, County Council, is an elected assembly and the successor of Jamtamót. This County Council was the role model for the rest of the Swedish County Councils when they were established in 1863.[21]

The province is also divided into primarily seven municipalities; Berg Municipality, Bräcke Municipality, Krokom Municipality, Ragunda Municipality, Strömsund Municipality, Åre Municipality and Östersund Municipality. The uninhabited part in northern Jämtland belongs to Dorotea Municipality and the area around Överturingen is a part of Ånge Municipality.

Though, even if these municipalities and the county are serving as administrative regions most Jamts still identify themselves with the parishes and with Jämtland as a province.

Physical geography

Jämtland is a large land-locked province in the heart of the Scandinavian peninsula in northern Europe. Jämtland stretches 315 kilometers in north-south direction and 250 kilometers in east-west direction and is equal in size with e.g. Ireland. Jämtland's western border is made out by Kölen which stretches throughout the province from north to south with branches into the landscape's southeastern parts. The fell massif is broken at some places by large valleys stretching all the way to the Norwegian Sea. These valleys have been used for centuries as paths connecting Jämtland to the west. The valleys were particularly heavily used during pilgrimages to Nidaros, the fourth most visited pilgrimage site during the medieval period. In fact no less than three pilgrim roads went through Jämtland.

The entire province is more or less a highland region with the highest peak being Storsylen, a peak in the Sylan mountain range with an altitude of 1 728 meters above sea level. Though this is not the highest peak in the mountain range, since that peak is in fact located on the other side of the border. Another large peak in Jämtland worthy of mention is Åreskutan (1 420 meters above sea level). The lowest point in the province is as low as 35 meters above sea level and is located in the eastern part of Jämtland.

Approximately 8 per cent of Jämtland's area is covered by water and the province has two larger streams, Ljungan and Indalsälven (also known as Jämtlandsälven). Both of which emanates from the Scandinavian Mountains and drains several lakes on their way eastwards to lower altitudes.

Climate

Jämtland has a temperate climate and belongs to the temperate zone's northernmost area. The climate in Jämtland is both humid continental and subarctic, depending on the location. The climate is greatly affected by the Norwegian Sea and the Atlantic Ocean, due to several mountain passes in Scandinavian mountain range.

In western Jämtland mild winters with excessive precipitation are common. This is because of the warm winds brought to the area by the Gulf Stream. The average precipitation in the Jamtish Fells is roughly 1 000 millimetres per year, with Skäckerfjällen as extreme with about 1 500 mm. The precipitation rates in the middle of the province are much more moderate. In fact the central and eastern parts of Jämtland have precipitation shortages, in Storsjöbygden the annual averages is as low as 500 mm. Due to the warm winds the temperature during the winters reaches its maximum in the fell region with about -7-8°C in Storlien and the environs. The coldest winter temperatures are found in the province's outskirts like Börtnan with roughly -11 °C. Maximum temperatures in the summer months average from the 14 °C in Jämtland's eastern parts to around 11 °C in the fell region. Though on certain mountain peaks the averages are usually as low as 5 °C.

The highest (34.0 °C) and lowest (-45.8 °C) temperatures ever recorded in Jämtland were found in its easternmost parts near Hammarstrand in 1947 and 1950.

Blizzards are common in Jämtland, and especially in the fell region. The most notable blizzard is the one that arose on New Year's Eve 1718 (see above). The heaviest winds in Jämtland may gust to 55 metres/s.

Wildlife

Flora

The Jamtish flora is heavily characterized by temperate coniferous forest, taiga, a forest inhabited by Norway spruce and pine trees. Among the two the Norway spruce is more common. The Norway spruce actually grows most densely in Jämtland together with the southern parts of Lapland. Here roughly 60 percent of the forests consist of spruces.

In Jämtland over 2,300 mineral-rich marshes (wetlands) containing a very high pH level have been located. These marshes cover an area of 550 square kilometers. 400 of these marshes are also very rich in chalk and because of the chalk-rich soil Jämtland displays the largest concentration of these type of marshes on the entire European continent. The chalk-rich soil has attracted several chalk-dependent plants, such as orchids, in Jämtland there are 19 different kinds of orchids.

Each province in Sweden has symbols associated with them and Jämtland's provincial flower is an extremely rare orchid, the Gymnadenia nigra, an orchid that's only common in the province and a few other places in central Scandinavia. Several kinds of berries are found in Jämtland like e.g. bilberry (blåbär), lingonberry (lyngbär) and cloudberry (referred to as mylhta in Jämtland).

Fauna

Due to the diversified natural environment in Jämtland it displays a great deal of different animals. The animal most commonly associated with Jämtland is (as already hinted) the moose. It is Jämtland's provincial animal and is referred to in dialect as simply djur, "animal". Moose may be found throughout Jämtland but to a lesser extent in the mountainous area in the province's eastern parts and in the north.

However northern Jämtland is the most densely populated brown bear habitat in the world. The brown bear (bjenn in Jamtish) is also more or less common throughout Jämtland. Other large predators in Jämtland include the cat gaupa (Eurasian lynx), the filfras meaning the glutton (wolverine) and smaller such as the Arctic fox. Jämtland has had populations of wolves (skrågg, gråbein) from time to time after it practically became extinct in Scandinavia during the 20th century. There are however currently no wolves with an established territory in Jämtland. There is also one large raptor in the province, the golden eagle.

The last native beaver in Sweden was shot in northern Jämtland 1871 at Bjurälven (bjur or björ is the Jamtish word for beaver). It was also in Jämtland that the beaver was reintroduced in Sweden from Norway in 1922. The current beaver population is quite large and common. Among the smaller mammals inhabiting Jämtland that are rare in the rest of Scandinavia are e.g. the taiga shrew and the northern birch mouse. The læmel, Norway lemming is also present in Jämtland and the latest major population boom usual for this species occurred in 2001.

Jämtland is inhabited by several mammals from the weasel family. Besides the already mentioned wolverine the oter, otter, is widespread in the province and common near several streams, the least or snow weasel exists, along with planted, released and escaped minks. The province is also home to the pine marten and the ermine. These mammals have often been hunted for their valuable fur, for Jämtland this is especially true for the ermine.

Among the deer the moose is as already stated common. Other deer are roe deer, red deer and reindeer, in the shape of Sami herds or wilded originally tame reindeers.

The provincial fish is the brown trout which is found together with common whitefish, grayling, European perch, Arctic char, burbot, salmon and the carnivorous northern pike. Roughly 250 types of birds have been observed in Jämtland. The species presence greatly varies, in the fells bluethroat, long-tailed skua, Eurasian dotterel, ptarmigan, Lapland and snow bunting are found. The forested region is inhabited by species such as hazel hen, black grouse, capercaillie, Siberian jay, three-toed woodpecker and rustic bunting. Several different types of owls dwells in the province and the provincial owl is the northern hawk owl.

Economy

The first humans came to Jämtland after the last ice age and later switched to a more agricultural lifestyle. Though the agriculture could not sustain the population so it was combined with a great deal of trading, hunting and iron production. When the rise of industrialism begun, Jämtland was one of the few Swedish regions that never became fully industrialized. Instead Jämtland supplied the Norrlandic coast with raw materials, mainly lumber. The focus in Jämtland's economy was directed towards tourism after the construction of the railroad, starting with the "clean air tourists" who came to experience the fresh air, to see the snow clad fells, the waterfalls and the natural environment. Today the tourism in Jämtland is dominated by winter sports and especially alpine skiing in various facilities in Åre, Bydalen, Storlien, Klövsjö, etc.

As Jämtland never industrialized the agricultural sector is larger compared to the rest of Sweden. In Jämtland County this sector employs 4,4 per cent of the labour force compared to 1,8 per cent for Sweden as whole.[22] Just like the rest of Sweden the public sector in Jämtland is large and the high taxes fund the public welfare.

Jämtland has large concentrations of uranium and deposits of e.g. gold, zinc, mica, silver, lead, iron and copper have been found. However, the only mines of importance in Jämtland's history are the former copper mines in Fröå and Huså.

Jämtland is heavily dominated by many small businesses and together with Härjedalen Jämtland has the second highest number of company owners in Sweden (in relation to the population), the highest number of enterprising women[23] and by far the most cooperatives.[24] Östersund is the centre of trade and commerce in Jämtland.

Population

With the exception of the city of Östersund and its surrounding areas, Jämtland is a very sparsely populated region. In Jämtland as a whole, there are only 3.4 people per square kilometre, and the population of 115,331[1] is unevenly distributed, with more than half its population (approximately 60 000) living in the Östersund area.

In Jämtland County (including the province of Härjedalen) the number of people living outside an urban area is 34% of the total population, making Jämtland one of the largest rural regions in Scandinavia. Most people in Jämtland live in Storsjöbygden, the area around lake Storsjön which includes Jämtland's only chartered city, Östersund, founded 1786 (now including Frösön), Krokom, Ås, Svenstavik, Nälden and Jämtland's second largest town Brunflo. This region is actually quite densely populated. The largest urban areas outside Storsjöbygden are primly the municipality seats Strömsund, Järpen, Bräcke and Hammarstrand, along with towns such as Hammerdal, Lit, and the ski resort Åre.

A resident or native of Jämtland is commonly referred to as Jamt (Swedish: jämte).

Famous natives

- Kjell Albin Abrahamson, journalist and author

- Georg Adlersparre, army commander, revolutionary leader of 1809

- Ann-Margret, actress, singer

- Ulf Dahlén, ice hockey player

- Alx Danielsson, racing driver

- Alexander Edler, ice hockey player (Vancouver Canucks)

- Allan Edwall, actor and author

- Gunder Hägg, runner

- Emma Härdelin, singer in bands Garmarna and Triakel

- Peja Lindholm, curler

- Henrik Lundqvist, ice hockey player (New York Rangers)

- Bodil Malmsten, novelist

- Magnus Nilsson, chef (Fäviken)

- Annika Norlin, pop artist

- Anna Ottosson, alpine skier

- Helge Palmcrantz, inventor

- Pehr Wilhelm Wargentin, astronomer and father of Statistics Sweden

- Hans Blix former UNMOVIC chairman

- Örjan Sandler Olympic bronze medalist in speed skating

- Sigvard Ericsson Olympic gold and silver medalist in speed skating

Culture

The culture of Jämtland has been greatly affected by the fact that Jämtland's never had an upper class, since the population have mostly consisted of free sovereign farmers with wide connections and a strong regional identity.[25] This has been the case for many generations. When Christian IV of Denmark punished the Jamts severely after having sworn the Swedish king their allegiance (see above) by turning them into tenant farmers and abolished their seal, he told them to stay put on their farms. They did not heed this call but instead sought help from their own organized advisors and "the land's defense", an insolence that further outraged the Danish king. Jämtland started out free and remained autonomous during its time as a Norwegian dependency. Because of Jämtland's historical background the local culture shows great similarities with the Norwegian farm culture.

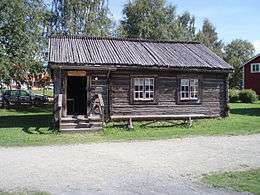

Today, the history of Jämtland is exhibited in the regional museum Jamtli in Östersund. The museum consists of an open-air section with historical buildings, as well as an indoor museum which houses exhibitions about the region's cultural history, from the Stone Age until modern times. Local history has been very popular in Jämtland for over 100 years, due to the extensive cultural home ground movement that emerged in the late 19th and early 20th century. The movement founded Jamtli to preserve the cultural heritage.

Lifestyle

The culture in Jämtland has been marked by the stages in human development; the hunting-gathering stage, the semi-nomadic herding stage, the fully agricultural stage and the modern technological stage.

Remnants from the hunter-gathering stage is first and foremost hunting itself. Jämtland's population remained in this stage for a very long time due to the hunters ability to sustain the population. Today the moose hunt is regarded by many Jamts as the major holiday of the year. When the first humans came to Jämtland they brought dogs with them as helpers. The local dog, Jämthund, is a canine breed eponymous to Jämtland. Even if it is not explicitly stated, popular perception holds that the dog depicted in the coat of arms is of that breed. The Jämthund is often described having a wolf-like appearance.

One of the first things Tacitus mentions in his work Germania is that the Germanic people treasure their animals above all else. Tacitus also concludes that the Germanic people found cultivation repulsive. Instead, he states, the Germanic people devote themselves to food and sleep and besides that they prefer to remain idle. All of this, to certain extents, applied to Jämtland. When the people of Jämtland settled down they relied mostly on pastoralism (transhumance). Their animals were the source of wealth and they were therefore loved by their owners. This love for the livestock has manifested itself in the dialect, a male nipple is called bokkjen (the buck) and a female nipple is known as geita (the goat).

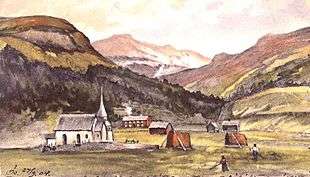

In Jämtland the Scandinavian inland transhumance, buföring, has always been more important than cultivation. In fact it was crucial to take care of the livestock and supply them with food, and rewarding. Every summer for several weeks, from May to September, gjetaran (herd boys) and butøusan (herd girls, bu is cognate to "booth") followed and guarded kreka, the critter, on their way to a grazing land on higher altitudes where several critter houses had been raised. The common animals taken out on these journeys were gjettran (Jämtland goats) and kynnan (the fell cows) a white, brisk and headstrong cow race, lacking horns. It was a hard work and it depended on cooperation between males and females. This lifestyle lived on for thousand years and it was first in the 1950s it became obsolete. This tradition has however been resurrected as of late, mostly for touristic purposes.

When the population settled down the society greatly changed, first coexisting with the older societies, later absorbing them. Trade became much more important, a political institution elected by the people came into existence, the very same institution whose successor is the current County Council. Jämtland got its name and a somewhat hierarchical social structure emerged, though, as already pointed out, Jämtland never had an upper class. Strong families such as Skanke and Blix did exist though and on the countryside in Jämtland people still live in networks of relatives, families. Where they provide a second social security for many, in the rest of Sweden and in e.g. Östersund this has completely or almost entirely been replaced by public welfare.

Cuisine

Much of Jämtland's cuisine is remnant from the herding stage. Just like other Scandinavians, it is common among Jamts to drink milk throughout their entire life. There are many different types of Jamtish dairy products, especially cheese, since it was by far the easiest way to conserve milk. Mesost is particularly associated with Jämtland and also e.g. a local variant of cottage cheese called grynost. In Jämtland there are several small dairies in the villages, most famous is the one in Skärvången. Other products associated with Jämtland are the soft whey butter, long fil, kjesfil, flautgröt "cream porridge", tunnbröd, a version of palt called kams, klobb etc.

The ancient practice of brewing Julöl (yule beer) persists even today with the microbrewery Jämtlands Bryggeri in Pilgrimstad.

Local projects such as the internet portal Food of Jämtland and the trading mark Smakriket Jämtland'' (the "taste realm" Jämtland) are two major contributors in marketing, preserving and developing the cuisine of Jämtland.

Some of the newest merchandises in Jämtland are a sparkling wine made of birch sap and a sausage called Jämtlandsfalu, wilderness juice, the snaps kallsup and tunnbröd chips.

Folklore

The folklore of Jämtland mostly correspond to Scandinavian folklore as whole, although the folklore is seldom regarded as popular belief nowadays, with one major exception, Storsjöodjuret.

According to legend it is believed that Storsjön (literally the Great Lake) harbors a large lake creature, Storsjöodjuret. There are many witness reports but the creature's existence remains to be established conclusively. Regardless of any proven existence, Storsjöodjuret was officially placed under the protection of a degree issued in 1986 by the County Administrative Board to guarantee its safety from hunters and fortune seekers, the protection was lifted in November 2005.[26] The first description of Storsjöodjuret was made in this tale from 1635;

A long, long time ago two trolls, Jata and Kata, stood on the shores of the Great Lake brewing a concoction in their cauldrons. They brewed and mixed and added to the liquid for days and weeks and years. They knew not what would result from their brew but they wondered about it a great deal. One evening there was heard a strange sound from one of their cauldrons. There was a wailing, a groaning and a crying, then suddenly came a loud bang. A strange animal with a black serpentine body and a cat-like head jumped out of the cauldron and disappeared into the lake. The monster enjoyed living in the lake, grew unbelievably larger and awakened terror among the people whenever it appeared. Finally, it extended all the way round the island of Frösön, and could even bite its own tail. Ketil Runske bound the mighty monster with a strong spell which was carved on a stone and raised on the island of Frösön. The serpent was pictured on the stone. Thus was the spell to be tied till the day someone came who could read and understand the inscription on the stone.

Puken is a magical ball of yarn summoned by a witch to draw objects to her. It often steals milk to the witch by milking cows.[27]

Just like in the rest of the world dragons have been known for a long time. In Jämtland they resemble brooms, that flies quickly and strikes down where treasuries are buried.[28]

Sjörå is a keeper of freshwater, that master fish, aas and lakes. It is similar to the Jamtish skogskjæringa "wife of the forest". A being that, at day, takes the appearance of a rauvtjuksa "red tail", a bird seen as ominous in Jamtish folklore. When in physical form her tail is always apparent. She tries to lure men to have sexual intercourse with her. The skogsrå is not the same creature as skogskjæringa in Jamtish folklore, it is the keeper of the forest and master all the animals in it. It takes on the shape of a moose during hunting season, and grows larger and larger if hit by bullets and eventually forces the hunters out. It can however, be slain with a silver bullet.[29]

Tomten is a common creature, it is quite tall and has an eye in the middle of his forehead. It is the keeper of barns and a very capricious being, though he usually brings luck.[30]

The Nix, Näkkjen, is a common mythical creature, in Jämtland it refers to a male water spirit whose music was dangerous to women. Each year in the town of Hackås in southern Jämtland an annual traditional music contest Årets Näck is held where each contestant impersonates the Nix.

In Jämtland the vættir/dwarves goes by the name jolbyggar "earth builders". They herd large white goats and cows and live underground, they are considered innocuous though sometimes they exchange an unbaptized child for a so-called bytningsbarn. They are commonly associated with the grazing lands.[30] They also go by the names småruskan, smågubban and småtussan.

Folk costumes

Jämtland has several different types of folk costumes or bunads. Unlike certain regions in Scandinavia a unitary bunad did not exist in Jämtland's parishes, with the exception of Hammerdal parish with its brown-striped clothing.

Usually Jämtland is divided into three different clothing parts, the North Jamtish (Hammerdal), the East Jamtish (Ragunda) and the Great Jamtish area, covering the rest and the majority of Jämtland.

The North Jamtish clothing part is typically influenced by the folk costumes of northern Ångermanland and to a lesser degree Lapland, with the exception of Frostviken parish settled by Trønders in the 18th century. The East Jamtish part is the least old-fashioned of the three with many changes done to the costumes through time, making them closer to the kind used at the Swedish coast, rather than the others in Jämtland. The Great Jamtish part has typically old-fashioned and conservative homogeneous bunads with blue socks, red knitted caps among the males, dark bounded caps for ladies and coloured for girls. The skirts are usually of a single colour and the men have blue or black hodden coats, with yellow chamois leather pants made from moose skin.

Dialects

The genuine dialect of Jämtland is Jamtish. The speakers of the dialect refer to it as Jamska ([ˈjamskɐ]), which is a definite form that translates to English as "the Jamtish". However, due to the lack of a well-established English name of the dialect both Jamtish and Jamtlandic are used.

Jamtish is in fact a group of dialects and there are distinctive dialects in every parish. Though they are usually classified in four groups; framlänningsmålet "the Central Jamtish tongue", opplänningsmålet (spoken in Western Jämtland), Southwest Jamtish and Northern Jamtish. The dialects in eastern Jämtland are sometimes considered as a fifth group of Jamtish, but also as dialects more related to the Swedish dialects spoken in Ångermanland. In the very north of Jämtland lidmål, a version of Trøndersk, is spoken. Jamtish is spoken by 50 000 people at most living in Jämtland and in other areas of Sweden, particularly the capital Stockholm.

|

Where d'you find a life of ease, green grass Where d'you think the bugs don't bite It's to the east of the waning moon |

Language

Even if the Jamtish official status is a dialect many Jamtish people see it as an own language. There are multiple activists that are trying to make the Swedish government recognise Jamtish as a minority language just as Yiddish or Sami have become one. The claimers say to look at the different words and pronunciations of them. Whether or not it is its own language has been widely debated since the early 20th century.

Provincial character

Historically each province in Sweden has been known for a specific provincial character or volksgeist. This was a field of intense research in Sweden earlier but is viewed somewhat unmodern and considered prejudice today.

The provincial character of Jämtland was often portrayed as cheerful and the population have historically been known for their hospitality. Before the dawn of the railway it was common among farmers to leave their doors unlocked when the annual summer journey to the critter houses was due, often with the table set with food for travelers.

The faring traditions of Jämtland are also very characteristic. The Jamts were known to neglect the agriculture and instead take on long trading journeys all over Scandinavia to various markets such as the ancients ones in Levanger and Gregorius market on Frösön. This was regarded as sheer pleasure in itself and not as something they were obligated to do. In the middle of the 18th century Jämtland's population was roughly 20 000 and it was common that over 1 000 Jamts were present during Marsimartnan in Levanger, it is also claimed that the city was built solely on spikes from Jämtland before the fire in the 19th century. The journeys took place during the winters when the landscape was more accessible (when swamps, lakes and tarns froze to ice) and was conducted by males, which left the females in complete charge of the household and the property. The journeys were well-organized expeditions and no one traveled alone. These traditions has awarded the Jamt with traits such as enterprising and energetic. The Jamts' attempts to avoid tariffs were very successful which greatly angered Swedish officials through time. These journeys eventually stopped once the railway came, though it has recently been renewed by locals. Some say that the heritage from this age lives on, given the high number of enterprises per capita.

Republic of Jamtland

In the 1960s, an independence movement calling itself the "Republic of Jamtland" was created by humorist/actor/director Yngve Gamlin. Motivated on paper as an attempt to return the province to Jamtlandic control, the republic was given some form of recognition in 1967 when Mr. Gamlin was invited to an event for visiting statesmen hosted by Swedish prime minister Tage Erlander. Described in some sources as a form of criticism against centralized Swedish government and in others as a marketing ploy, it is likely that both played some part in its foundation (Republic officials typically describe it as "51 percent serious"). The republic has a self-styled flag and national anthem (Jämtlandssången) and the independence movement hosts the annual Storsjöyran event in the capital, Östersund.

Sports

Football in the province is administered by Jämtland-Härjedalens Fotbollförbund. The clubs overseen by the association include Myssjö-Ovikens IF.

References

- Ekerwald, Carl-Göran (2004). Jämtarnas historia intill 1319. Östersund: Jengel - Förlaget för Jemtlandica.

- Persson, Margareta; Per-Lennart Persson; Bo Oscarsson; Berta Magnusson; Nils Simonsson (1986). Dä glöm fell int Jamska. Offerdal: Margareta Persson.

- Nils-Arvid Bringéus; Karl Johan Eklund; Gunnar Olof Hyltén-Cavallius; et al. (1963). Björkquist, Lennart (ed.). Jämten 1964. Östersund: Heimbygdas Förlag.

- Steinar Imsen; Kerstin Modin; et al. (1995). Rentzhog, Sten (ed.). Jämten 1996. Östersund: Jamtli/Jämtlands läns museum.

- Carl-Göran Ekerwald; Ville Roempke; Frans Järnankar; et al. (1996). Rentzhog, Sten (ed.). Jämten 1997. Östersund: Jamtli/Jämtlands läns museum.

- Hans Westlund; Håkan Larsson; Merete Røskaft; et al. (1999). Rentzhog, Sten (ed.). Jämten 2000. Östersund: Jamtli/Jämtlands läns museum.

- Rumar, Lars (1998). Historia kring Kölen. Östersund: Jamtli/Jämtlands läns museum.

Notes

- "Folkmängd i landskapen den 31 december 2016" (in Swedish). Statistics Sweden. March 21, 2017. Retrieved 2017-11-27.

- Ekerwald, Carl-Göran (2004). Jämtarnas historia (in Swedish), 124. "Svaret är att Jämtland före 1178 var ett självständigt bondesamfund, "dei vart verande ein nasjon för seg sjöl", för att nu citera Halfdan Koht.. Jämtland var en bonderepublik.."

- Jämtland - Turism Archived 2015-10-06 at the Wayback Machine, bracke.se

- Historien om Republiken Jämtland, lamgo.se

- Jamtamot i Uppsala, jamtamot.org

- Hellquist, Elof (1922). Svensk etymologisk ordbok. Stockholm: Gleerups förlag. p. 285.

- "Jamtlandsvegen" (in Norwegian). Verdal Historielag. Archived from the original on 2009-01-08. Retrieved 2008-06-27.

- Oscarsson, Bo (1986). "1000 år av frihet", in Margareta Persson: Dä glöm fell int jamska (in Swedish). Offerdal: Margareta Persson, 20.

- "Jamtlis historia" (in Swedish). Jamtli. Retrieved 2008-06-27.

- Ekerwald, Carl-Göran (2004). Jämtarnas historia, 163.

- Ekerwald, Carl-Göran (2004). Jämtarnas historia, 123.

- Ekerwald, Carl-Göran (2004). Jämtarnas historia, 117.

- Ekerwald, Carl-Göran (2004). Jämtarnas historia, 154.

- Rentzhog, Sten (1996). "Tidernas Kyrka", in Sten Rentzhog: Jämten 1997 (in Swedish), 23.

- Rentzhog, Sten (1996). "Tidernas Kyrka", in Sten Rentzhog: Jämten 1997 (in Swedish), 29. "bönder emellan ingen annan rang än ålder och levnadsår"

- Rentzhog, Sten (1996). "Tidernas Kyrka", in Sten Rentzhog: Jämten 1997 (in Swedish), 30.

- Rumar, Lars (1998). Historia kring Kölen (in Swedish), 50.

- The article Jämtland, in the encyclopædia Nationalencyklopedin.

- Nevéus, Clara (1992). Ny Svensk Vapenbok (in Swedish). Ill. by Jacques de Wærn. Stockholm, Sweden: Streiffert & Co Bokförlag. p. 24.

- "Jämtland". Heraldisk Databas (in Swedish). Swedish Heraldry Society. Retrieved 2013-08-18.

- Larsson, Håkan (1999). "Jämtlands landsting modell för hela landet?", in Sten Rentzhog: Jämten 2000 (in Swedish), 98-100.

- "Sysselsatta per bransch" (in Swedish). Regionfakta.com. Archived from the original on 2007-11-28. Retrieved 2008-02-23.

- Godin, Lisbeth. "Jämtlandskvinnor mest företagsamma i landet" (in Swedish). Confederation of Swedish Enterprise. Archived from the original on 2007-12-21. Retrieved 2008-02-23.

- Trapp, Mikael. "Kooperativ är i ropet och jämtarna är bäst" (in Swedish). Östersunds-Posten. Archived from the original on February 26, 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-23.

- Ekerwald, Carl-Göran (2004). Jämtarnas historia, 27.

- Scotsman.com

- Bringéus, Nils-Arvid (1963). "Folktraditioner från Jämtland" in Lennart Björkquist: Jämten 1964 (in Swedish), 94

- Bringéus, Nils-Arvid (1963). "Folktraditioner från Jämtland" in Lennart Björkquist: Jämten 1964 (in Swedish), 94-95

- Bringéus, Nils-Arvid (1963). "Folktraditioner från Jämtland" in Lennart Björkquist: Jämten 1964 (in Swedish), 96-97

- Bringéus, Nils-Arvid (1963). "Folktraditioner från Jämtland" in Lennart Björkquist: Jämten 1964 (in Swedish), 98

- "Triakel Songs from 63 Degrees N". NorthSide - Nordic Roots Music. Archived from the original on 2008-05-21. Retrieved 2008-07-02.

External links

- Jamtland - Official tourist site of Jämtland & Härjedalen

- Experience Winter in Jämtland Härjedalen - Tourist info

- Jamtland - history and language

- Jämtland Wildflowers