Capture of Gibraltar

The Capture of Gibraltar by Anglo-Dutch forces of the Grand Alliance occurred between 1 and 4 August 1704 during the War of the Spanish Succession.[1] Since the beginning of the war the Alliance had been looking for a harbour in the Iberian Peninsula to control the Strait of Gibraltar and facilitate naval operations against the French fleet in the western Mediterranean Sea. An attempt to seize Cádiz had ended in failure in September 1702, but following the Alliance fleet's successful raid in Vigo Bay in October that year, the combined fleets of the 'Maritime Powers', the Netherlands and England, had emerged as the dominant naval force in the region. This strength helped persuade King Peter II of Portugal to sever his alliance with France and Bourbon-controlled Spain, and ally himself with the Grand Alliance in 1703 as the Alliance fleets could campaign in the Mediterranean using access to the port of Lisbon and conduct operations in support of the Austrian Habsburg candidate to the Spanish throne, the Archduke Charles, known to his supporters as Charles III of Spain.

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Gibraltar |

|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

Prince George of Hesse-Darmstadt represented the Habsburg cause in the region. In May 1704 the Prince and Admiral George Rooke, commander of the main Grand Alliance fleet, failed to take Barcelona in the name of 'Charles III'; Rooke subsequently evaded pressure from his allies to make another attempt on Cádiz. In order to compensate for their lack of success the Alliance commanders resolved to capture Gibraltar, a small town on the southern Spanish coast. Following a heavy bombardment the town was invaded by English and Dutch marines and sailors. The governor, Diego de Salinas, agreed to surrender Gibraltar and its small garrison on 4 August. Three days later Prince George entered the town with Austrian and Spanish Habsburg troops in the name of Charles III of Spain. The Grand Alliance failed in its objective of replacing Philip V with Charles III as King of Spain, but in the peace negotiations Gibraltar was ceded to Britain.

Background

At the start of the War of the Spanish Succession Portugal was nominally an ally of the Bourbons: France under Louis XIV, and Spain under his grandson, Philip V. Although not a belligerent, Portugal's harbours were closed to the enemies of the Bourbon powers – principally the vessels of England and the Dutch Republic. However, following the Anglo-Dutch naval victory at Vigo Bay in 1702 the balance of naval forces had swung in favour of the Grand Alliance. Having now the ability to cut off Portugal's food supplies and trade (particularly gold from Brazil) it was not hard for the Allied diplomats to induce King Peter II to sign the Methuen Treaties of May 1703 and join the Alliance.[8] Once Peter II had committed himself to war the Alliance fleets gained access to Portugal's harbours, in particular the port of Lisbon. In return for his allegiance Peter II had demanded military and financial aid and territorial concessions in Spain; he had also asked that the Alliance send to Lisbon Emperor Leopold I's younger son, Charles – the Alliance's Habsburg candidate to the Spanish throne – to demonstrate the earnestness of their support.[8] Known to his supporters as Charles III of Spain, the young pretender arrived in Lisbon – via London – with George Rooke's fleet on 7 March 1704, amid great celebrations.[9]

Apart from the failed Grand Alliance attempt to take Cádiz in 1702, and the subsequent attack on the Spanish treasure fleet in Vigo Bay, the war had thus far been limited to the Low Countries and Italy. With Portugal's change of allegiance, however, the war moved towards Spain. In May 1704 the court at Lisbon received news that French and Spanish troops had crossed the frontier into Portugal. This army of approximately 26,000 men under Philip V and the Duke of Berwick scored several victories on the border: Salvaterra fell on 8 May, Penha Garcia on 11 May, Philip V personally oversaw the fall of Castelo Branco on 23 May, and T'Serclaes captured Portalegre on 8 June.[10] But without supply for their forces, the coming summer heat made it impossible for them to continue with the campaign, and Philip V returned to Madrid on 16 July to a hero's welcome. However, the heat did not affect the war at sea where the Alliance was in a position of strength.[11]

Prelude

Using Lisbon as an improvised forward base Admiral Rooke's Anglo-Dutch fleet ventured into the Mediterranean Sea in May 1704. After seeing the Levant trading fleet safely through the Strait of Gibraltar Rooke headed towards Nice to put himself in touch with Victor Amadeus II, Duke of Savoy. The Grand Alliance had planned for a naval attack upon the French base at Toulon in conjunction with the Savoyard army and the rebels of the Cévennes; but with Amadeus busy defending his capital Turin from French forces, the Toulon expedition was abandoned and Rooke sailed for the Catalan capital, Barcelona.[12]

Accompanying Rooke was Prince George of Hesse-Darmstadt who had enjoyed popularity amongst the Catalans as their governor at the end of the Nine Years' War. The Prince was the great exponent of the Barcelona plan; he had been in touch with the dissidents within Catalonia and counted on the appearance of the fleet to encourage a rising in favour of 'Charles III'.[13] On 30 May, under cover of the ships’ guns, Prince George landed with 1,200 English and 400 Dutch marines; but the governor of Barcelona, Don Francisco de Velasco, had managed to keep the city's disaffected elements quiet and Philip V's partisans on the alert. Moreover, the dissidents were incensed by the size of the Alliance force and had expected the personal appearance of 'Charles III'.[14] Ultimatums for Velesco to surrender on pain of bombardment were ignored, and the plans for an insurrection from within the city's walls failed to materialize. Rooke, fearing an attack from a French squadron, was impatient for departure. Prince George could do little more than order his local followers – a thousand in all – to disperse to their homes. The marines embarked on 1 June without loss.[15]

Meanwhile, the comte de Toulouse, one of Louis XIV’s illegitimate sons, was sailing towards the Straits with the fleet from Brest. News from Lisbon of the French manoeuvres reached Rooke on 5 June. Determined to prevent the junction of the Toulon and Brest fleets Rooke decided to risk a battle. However, owing to the foul bottoms of the Anglo-Dutch ships the swifter French fleet escaped Rooke's pursuit and arrived safely in Toulon; thenceforth, Toulouse became the commander of the enlarged French fleet, now known as the Grand Fleet of France. Rooke could not venture within range of the Toulon forts nor risk attack from a superior force so far from any port of refuge. He therefore turned back towards the Straits where the arrival of an English squadron under Cloudesley Shovell had put the Allies on a numerical parity with the French.[16]

Rooke met Shovell on 27 June off Lagos. Peter II and ‘Charles III’ sent word from Lisbon that they now wished another attempt to be made on Cádiz.[17] Methuen believed the place to be ungarrisoned and easy to take, but the admirals in the fleet remained sceptical,[18] especially when considering that they were not on this occasion carrying a force comparable to the failed attempt there two years earlier. Cádiz, however, was not the only potential target. As the Alliance fleet lay off Tetuan on the Barbary Coast, a council of war aboard Rooke's flagship discussed the need to please the two kings and save their own reputations. On 28 July the Alliance commanders considered the proposal of Prince George, now commander-in-chief of Alliance forces in the peninsula, for an attack on Gibraltar.[19]

The idea of attacking Gibraltar was old and widely spread. The ‘Rock’ had caught the attention of Oliver Cromwell, and later William III's and Queen Anne’s ministers had marked it for England. The Moors had previously shown interest in the Rock and fortified it with a castle whose ruins still remained. Emperor Charles V had added many other works; but its immediate operational benefit was negligible.[20] Gibraltar had little trade and its anchorage was unprotected – there was no question, at this time, of basing a fleet there.[21] Gibraltar was finally selected for its strategic value, weak garrison and to encourage the rejection of Philip V (the Bourbon Claimant) in favour of Charles III (the Habsburg claimant).[22]

Battle

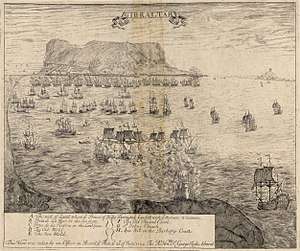

The Grand Alliance fleet crossed from Tetuan on 30 July; by 1 August Rooke, flying his flag in the Second Rate Royal Katherine, stood at the entrance to the bay while Admiral George Byng’s squadron (16 English under Byng and six Dutch ships under Rear Admiral Paulus van der Dussen) anchored inside, ranging themselves within the line of defences from the Old to the New Mole. The council of war had decided that Prince George would land with 1,800 English and Dutch marines on the isthmus under cover of a naval bombardment.[17] The marines landed at the head of the bay, and met with no resistance except for a small body of cavalry. They cut off Gibraltar from the mainland while the enemy on the nearby hills were dispersed by fire from two ships sent to the east of the rock.[24]

Prince George summoned the governor, Don Diego de Salinas, to surrender in the name of Charles III. He refused, and the garrison pledged its allegiance to Philip V. Although the governor was determined to resist he knew he did not have the means to do so: his earlier requests for reinforcements and military stores had always been in vain.[5] By his own account, Don Diego had ‘no more than fifty-six men of whom there were not thirty in service’ and could count on a few hundred civilian militia ‘of such bad quality that before they [the Allied fleet] arrived they began to run away.’ In addition, he had 100 cannon of various kinds but few were in a state to be fired, and fewer still had gunners to fire them.[5]

2 August passed in preliminaries. Don Diego, who in Trevelyan's words was prepared to ‘die like a gentleman’, sent back his defiant reply to the summons to surrender.[5] Byng's squadron warped themselves in along the sea front as close as the depth permitted and Captain Jumper brought the Lenox within actual musket range of the New Mole. These operations were carried out in a dead calm, and were not impeded by a few shots from the Spanish batteries. At midnight Captain Edward Whitaker of the Dorsetshire led a party against a French privateer anchored at the Old Mole which had been firing at the marines on the isthmus.[24]

About 05:00 the following day, 3 August, Byng's squadron of 22 ships fired in earnest on the crumbling walls and forts.[25] Tens of thousands of shells were fired in the attack. The actual damage done was small in proportion to the expenditure of the shot, but in view of the possible approach of the French fleet the job had to be done quickly or not at all.[24] Captain Whitaker acted as Byng's aide-de-camp, carrying his instructions from ship to ship, including the final order to cease firing six hours after they had begun.[25] As the smoke lifted Captain Jumper at the southern end of the line could discern the New Mole and the fort that commanded its abutment on the land. The defenders of the fort appeared to have fled, and Whitaker and Jumper agreed that a landing could be effected there unopposed. Rooke granted the request to attack, and a flotilla of row-boats raced for the New Mole.[25]

Landing

As the Grand Alliance prepared for their assault the priests, women, and children who had taken refuge at the chapel of Europa Point at southern end of the peninsula, began to return to their homes in the town. An English ship fired a warning shot in front of the civilian column forcing them back out of harm's way, but the shot was mistaken by the rest of the fleet as a signal to resume fire, and the bombardment began again. Under cover of the guns the landing party did its work.[25]

The foremost sailors clambered into the breached and undefended fort at the New Mole; however, by accident or design the magazine at the fort blew up. Some of the landing party carried lighted gun-matches and, according to Trevelyan, had forgotten the possibility of a powder-magazine. Whatever the cause of the explosion the Alliance suffered between 100–200 casualties.[26] A momentary panic ensued, for the survivors suspected an enemy-laid trap had caused the disaster. There was a rush for the boats, but at this critical moment Captain Whitaker arrived with reinforcements.[24] The landing was supported by a number of Catalan volunteers, for whom one of Gibraltar's main spots, Catalan Bay, bears its name.[27] Within a few minutes the attackers had rallied and proceeded north along the deserted ramparts of the seafront towards Gibraltar. On arriving near Charles V's southern wall of the town, Whitaker halted the sailors and hoisted the Union Flag in a bastion on the shore.[28]

Byng now came ashore with several hundred more seamen. Thus was the town invested by Byng in the south, as well as on its stronger northern side where the marines had landed with Prince George. Meanwhile, the party of the women and children stranded at Europa Point had been captured by English sailors. Rooke had given orders that the prisoners were not to be ill-treated, but the desire to recover these women was a further inducement for the defenders to end their resistance.[29] On 4 August, seeing all was lost, Don Diego agreed to terms that guaranteed the lives and property of those committed to his care.[30] Under the capitulation French subjects were taken prisoner, while any Spaniard who would take an oath of allegiance to 'Charles III' as King of Spain could remain in the town with religion and property guaranteed.

Aftermath

Orders were issued to respect civilians[31] as the Grand Alliance hoped to win over the population to their cause. Officers tried to maintain control but (as had happened two years previously in the raid on Cádiz) discipline broke down and the men[32] ran amok.[33] There were numerous incidents of rape, all Catholic churches but one (the Parish Church of St. Mary the Crowned, now the Cathedral) were desecrated or converted into military storehouses, and religious symbols such as the statue of Our Lady of Europe were damaged and destroyed. Angry Spanish inhabitants took violent reprisals against the occupiers. English and Dutch soldiers and sailors were attacked and killed, and their bodies were thrown into wells and cesspits.[34] After order was restored,[35][36] despite the surrender agreement promising property and religious rights,[37] most of the population left with the garrison on 7 August citing loyalty to Philip.[38] Several factors influenced the decision including the expectation of a counterattack[39] and the violence[40] during the capture, which ultimately proved disastrous for the Habsburg cause.[41] The subsequent siege failed to dislodge the Habsburg forces and the refugees settled around Algeciras and the hermitage of San Roque.[42] The Alliance's conduct aroused anger in Spain against the 'heretics', and once again the chance of winning over Andalusians to the Imperial cause was lost. Prince George was the first to complain, which was resented by Byng who had led the fighting and who in turn blamed the Prince and his few Spanish or Catalan supporters.[2] Rooke complained in a letter home that the Spaniards were so exasperated against the Alliance that ‘they use the prisoners they take as barbarously as the Moors’.[43] Spain attempted to retake Gibraltar in 1727 and most notably in 1779, when it entered the American Revolutionary War on the American side as an ally of France.[44]

The capture of Gibraltar was recognised as a great achievement in Lisbon and by all the trading interests in the Mediterranean.[2] A month after its capture Secretary of State Sir Charles Hedges described it as 'of great use to us [the English] for securing our trade and interrupting the enemy's'.[45] With the English navy established on the Straits the piratical Moors of the Barbary Coast became reluctant to attack English merchant shipping, and allied themselves with Queen Anne.[45] However, Gibraltar's immediate use as a port was limited for it could only take a few ships at a time, and ministers did not think they could keep it unless a garrison could be found for its security.[2] John Methuen recommended an English garrison. This was supplied by the marines that had helped take the place, and by several companies of regular troops. Gibraltar was, therefore, held by English troops and at English cost – but it was in 'Charles III's' name. A year later the Austrian candidate wrote to Queen Anne about “Ma ville de Gibraltar”. If he had succeeded in his attempt to ascend the throne in Madrid the difficulty of keeping Gibraltar for England would have been politically very great.[43]

The Alliance fleet returned to Tetuan to water. Before fresh orders came from Lisbon there was news of the approach of the French Grand Fleet under Toulouse. In an attempt by the French to retake Gibraltar, the one full-dress naval engagement of the war was fought off Málaga on 24 August; afterwards, French and Spanish troops battered at the land approaches, defended by a small garrison of sailors, soldiers, and marines.[45] In 1711, the British and French Governments started secret negotiations to end the war leading to the cession of Gibraltar to the British by the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713,[46] which remains a British overseas territory to this day.

See also

Notes

- All dates in the article are in the Gregorian calendar (unless otherwise stated). The Julian calendar as used in England after 1700 differed by eleven days. Thus, the main attack on Gibraltar began on 3 August (Gregorian calendar) or 23 July (Julian calendar). In this article (O.S) is used to annotate Julian dates with the year adjusted to 1 January. See the article Old Style and New Style dates for a more detailed explanation of the dating issues and conventions.

- Francis: The First Peninsular War: 1702–1713, 115

- Kramer, Johannes (1986). English and Spanish in Gibraltar. Buske Verlag, p.10, note 9. ISBN 3-87118-815-8

- 22 ships of the line(Byng’s squadron, 16 English and 6 Dutch) took part in the bombardment.

- Trevelyan: England Under Queen Anne: Blenheim, 410

- Francis: The First Peninsular War: 1702–1713, 114. Gibraltar garrison held 80 men. Militia and inhabitants supplied another 350. (Sources vary slightly)

- Trevelyan: England Under Queen Anne: Blenheim, 414. Almost all these casualties were taken when the fort near the New Mole blew up.

- Bromley: The New Cambridge Modern History VI: The Rise of Great Britain and Russia 1688–1725, 418

- Kamen: Philip V of Spain: The King who Reigned Twice, 33

- Lynn: The Wars of Louis XIV: 1667–1714, 295–96

- Kamen: Philip V of Spain: The King who Reigned Twice, 38

- Trevelyan: England Under Queen Anne: Blenheim, 405

- Francis: The First Peninsular War: 1702–1713, 104

- Stanhope: History of the War of the Succession in Spain, 97. Velasco had been governor of Catalonia in 1697 at the time of the French siege, and had lately been reappointed.

- Francis: The First Peninsular War: 1702–1713, 107

- Trevelyan: England Under Queen Anne: Blenheim, 406

- Le Fevre & Harding: Precursors of Nelson: British Admirals of the Eighteenth Century, 68

- Francis: The First Peninsular War: 1702–1713, 109. A naval reconnaissance confirmed Rooke’s opinion about the supposed weakness of the port’s defences.

- Francis: The First Peninsular War: 1702–1713, 109

- Stanhope: History of the War of the Succession in Spain, 98

- Roger: The Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain 1649–1815, 169

- Sir William Godfrey Fothergill Jackson (1987). The Rock of the Gibraltarians: A History of Gibraltar. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-8386-3237-6.

Consideration was given to what other project might be undertaken by Rooke's powerful fleet of fifty-two English and ten Dutch ships of the line. In the debate, three reasons were given for selecting Gibraltar as the target: the place was indifferently garrisoned; its possession would be of great value during the war; and its capture would encourage the Spaniards in southern Spain to declare in favour of the Habsburgs.

- Kamen: Philip V of Spain: The King who Reigned Twice. 39

- Francis: The First Peninsular War: 1702–1713, 110

- Trevelyan: England Under Queen Anne: Blenheim, 411

- Stanhope puts the figure at 40 dead and 60 wounded: Trevelyan states 200 casualties: Francis states that 40 sailors were killed and 'a few Spaniards'.

- Bronchud, Miguel (2007). The Secret Castle: The Key to Good and Evil. DigitalPulp Publishing.com, p.112. ISBN 0-9763083-9-8

- Trevelyan: England Under Queen Anne: Blenheim, 412. The Union Flag had been in frequent use since the Union of the Crowns of England and Scotland in 1603.

- Francis: The First Peninsular War: 1702–1713, 111

- "Why is Gibraltar British?". The Great Siege Gibraltar. Gibraltar Heritage Trust. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- George Hills (1974). Rock of contention: a history of Gibraltar. Hale. p. 165. Retrieved 7 April 2011.Ormonde issued a proclamation. "They were come not to invade or conquer any part of Spain or to make any acquisitions for Her Majesty Queen Anne...but rather to deliver Spaniards from the mean subjection into which a small and corrupt party of men have brought them by delivering up that former glorious monarchy to the dominion of the perpetual enemies of it, the French" He laid particular stress on the respect that was to be shown to priests and nuns - "We have already ordered under pain of death of officers and soldiers under out command not to molest any person of what rank or quality so ever in the exercise of their religion in any manner whatsoever.

- G. T. Garratt (March 2007). Gibraltar and the Mediterranean. Lightning Source Inc. p. 44. ISBN 9781406708509. Retrieved 7 April 2011.One has but to read the books left to us by the sailors to realize the peculiar horror of the life between-decks. Cooped up there, like sardines in a tin, were several hundreds of men, gathered by force and kept together by brutality. A lower-deck was the home of every vice, every baseness and every misery

- David Francis (1 April 1975). The First Peninsular War: Seventeen-Two to Seventeen-Thirteen. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 115. ISBN 9780312292607. Retrieved 7 April 2011.But some of the sailors, before they could be recalled to their ships broke loose in the town and plundered the inhabitants

- Jackson, p. 99.

- George Hills (1974). Rock of contention: a history of Gibraltar. Hale. p. 175. Retrieved 7 April 2011."Great disorders", he found, "had been committed by the boats crews that came on shore and marines; but the General Officers took great care to prevent them, by continually patrolling with their sergeants, and sending them on board their ships and punishing the marines

- Allen Andrews (1958). Proud fortress; the fighting story of Gibraltar. Evans. p. 35. Retrieved 7 April 2011.a few of them hanged as rioters after the sacking. One Englishman had to throw dice with a Dutchman to determine who should hang pour encourager les autres. They stood under the gallows and diced on a drum. The Englishman threw nine to the Dutchman's ten, and suffered execution before his mates.

- Sir William Godfrey Fothergill Jackson (1987). The Rock of the Gibraltarians: a history of Gibraltar. Farleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 99. ISBN 9780838632376. Retrieved 7 April 2011. Article V promised freedom of religion and full civil rights

- Frederick Sayer (1862). The history of Gibraltar and of its political relation to events in Europe. Saunders. p. 115. Retrieved 4 February 2011.Letter Of The Authorities To King Philip V. 115 Sire, The loyalty with which this city has served all the preceding kings, as well as your Majesty, has ever been notorious to them. In this last event, not less than on other occasions, it has endeavoured to exhibit its fidelity at the price of lives and property, which many of the inhabitants have lost in the combat; and with great honour and pleasure did they sacrifice themselves in defence of your Majesty, who may rest well assured that we who have survived (for our misfortune), had we experienced a similar fate, would have died with glory, and would not now suffer the great grief and distress of seeing your Majesty, our lord and master, dispossessed of so loyal a city. Subjects, but courageous as such, we will submit to no other government than that of your Catholic Majesty, in whose defence and service we shall pass the remainder of our lives; departing from this fortress, where, on account of the superior force of the enemy who attacked it, and the fatal chance of our not having any garrison for its defence, except a few poor and raw peasants, amounting to less than 300, we have not been able to resist the assault, as your Majesty must have already learnt from the governor or others. Our just grief allows us to notice no other fact for the information of your Majesty, but that all the inhabitants, and each singly, fulfilled their duties in their several stations; and our governor and alcalde have worked with the greatest zeal and activity, without allowing the horrors of the incessant cannonading to deter them from their duties, to which they attended personally, encouraging all with great devotion. May Divine Providence guard the royal person of your Majesty, Gibraltar, August 5th (N. S.), 1704.

- David Francis (1 April 1975). The First Peninsular War: Seventeen-Two to Seventeen-Thirteen. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 115. ISBN 9780312292607. Retrieved 7 April 2011. ...plundered the inhabitants. Partly on account of this, partly because they expected Gibraltar to be retaken soon, all the inhabitants except a very few...chose to leave

- Sir William Godfrey Fothergill Jackson (1987). The Rock of the Gibraltarians: a history of Gibraltar. Farleigh Dickinson University Press. pp. 99–100. ISBN 9780838632376. Retrieved 7 April 2011. Although Article V promised freedom or religion and full civil rights to all Spaniards who wished to stay in Habsburg Gibraltar, few decided to run the risk of remaining in the town. Fortresses changed hands quite frequently in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The English hold on Gibraltar might be only temporary. When the fortunes of war changed, the Spanish citizens would be able to re-occupy their property and rebuild their lives. ... Hesse's and Rooke's senior officers did their utmost to impose discipline, but the inhabitants worst fears were confirmed: women were insulted and outraged; Roman Catholic churches and institutions were taken over as stores and for other military purposes ...; and the whole town suffered at the hands of the ship's crew and marines who came ashore. Many bloody reprisals were taken by inhabitants before they left, bodies of murdered Englishmen and Dutchmen being thrown down wells and cesspits. By the time discipline was fully restored, few of the inhabitants wished or dared to remain.

- David Francis (1 April 1975). The First Peninsular War: Seventeen-Two to Seventeen-Thirteen. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 115. ISBN 9780312292607. Retrieved 7 April 2011. So the damage was done and the chance of winning the adherence of the Andalusians was lost.

- Sir William Godfrey Fothergill Jackson (1987). The Rock of the Gibraltarians: a history of Gibraltar. Farleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 100. ISBN 9780838632376. Retrieved 7 April 2011.

- Trevelyan: England Under Queen Anne: Blenheim, 414

- "Gibraltar." Microsoft Encarta 2006 [DVD]. Microsoft Corporation, 2005.

- Trevelyan: England Under Queen Anne: Blenheim, 415

- Sir William Godfrey Fothergill Jackson (1987). The Rock of the Gibraltarians: a history of Gibraltar. Farleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 113. ISBN 9780838632376. Retrieved 7 April 2011.

References

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Bromley, J. S. (ed.) (1971). The New Cambridge Modern History VI: The Rise of Great Britain and Russia 1688–1725. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-07524-6

- Francis, David (1975). The First Peninsular War: 1702–1713. Ernest Benn Limited. ISBN 0-510-00205-6

- Kamen, Henry (2001). Philip V of Spain: The King who Reigned Twice. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-08718-7

- Jackson, William G. F. (1986). The Rock of the Gibraltarians. Cranbury, NJ: Associated University Presses. ISBN 0-8386-3237-8.

- Le Fevre, Peter & Harding, Richard (eds.) (2000). Precursors of Nelson: British Admirals of the Eighteenth Century. Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1-86176-062-0

- Lynn, John A (1999). The Wars of Louis XIV: 1667–1714. Longman. ISBN 0-582-05629-2

- Roger, N.A.M. (2006). The Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain 1649–1815. Penguin ISBN 0-14-102690-1

- Stanhope, Philip (1836). History of the War of the Succession in Spain. London

- Trevelyan, G. M. (1948). England Under Queen Anne: Blenheim. Longmans, Green & Co.

.svg.png)