Culture of Iran

The Culture of Iran (Persian: فرهنگ ایران), also known as Culture of Persia, is one of the most influential cultures in the world. Iran is considered as one of the cradles of civilization,[1][2][3][4] and due to its dominant geo-political position and culture in the world, Iran has heavily influenced cultures and peoples as far away as Italy, Macedonia, and Greece to the West, Russia and Eastern Europe to the North, the Arabian Peninsula to the South, and the Indian subcontinent and East Asia to the East.[1][2][5] Iran's rich history has had a significant impact on the world through art, architecture, poetry, science and technology, medicine, philosophy and engineering.

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Iran |

|---|

.svg.png) |

|

|

| Iranian art |

|---|

|

| Visual arts |

| Decorative arts |

| Literature |

| Performance arts |

| Other |

An eclectic cultural elasticity has been said to be one of the key defining characteristics of the Iranian identity and a clue to its historical longevity.[6] The first sentence of prominent Iranologist Richard Nelson Frye's book on Iran reads:

- "Iran's glory has always been its culture." [7]

Furthermore, Iran's culture has manifested itself in several facets throughout the history of Iran as well as the South Caucasus, Central Asia, Anatolia, and Mesopotamia.

Art

Iran has one of the oldest, richest and most influential art heritages in the world which encompasses many disciplines including literature, music, dance, architecture, painting, weaving, pottery, calligraphy, metalworking and stonemasonry.

Iranian art has gone through numerous phases, which is evident from the unique aesthetics of Iran. From the Elamite Chogha Zanbil to the Median and Achaemenid reliefs of Persepolis to the mosaics of Bishapur.

The Islamic Golden Age brought drastic changes to the styles and practice of the arts. However, each Iranian dynasty had its own particular foci, building upon the previous dynasty's, all of which during their times were heavily influential in shaping the cultures of the world then and today.

Language

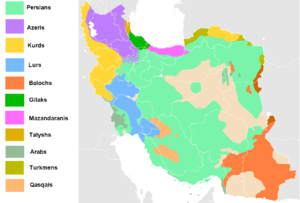

Several languages are spoken throughout Iran. Languages from the Iranian, Turkic, and Semitic language families are spoken across Iran. According to the CIA Factbook, 78% of Iranians speaks an Iranian language as their native tongue, 18% speak a Turkic language as their native tongue and 2% speak a Semitic language as their native tongue while the remaining 2% speak languages from various other groups.[8] It must be noted that although the Azerbaijanis speak a Turkic language, due to their culture, history and genetics, they are often associated with the Iranian peoples.

The predominant language and national language of Iran is Persian, which is spoken fluently across the country. Azerbaijani is spoken primarily and widely in the northwest, Kurdish and Luri are spoken primarily in the west, Mazandarani and Gilaki spoken in the regions along the Caspian Sea, Arabic primarily in the Persian Gulf coastal regions, Balochi primarily in the southeast, and Turkmen primarily in northern border regions. Smaller languages spread in other regions notably include Talysh, Georgian, Armenian, Assyrian, and Circassian, amongst others.

Ethnologue estimates that there are 86 Iranian languages, the largest among them being Persian, Pashto, and the Kurdish dialect continuum with an estimated 150-200 million native speakers of the Iranian languages worldwide.[9][10][11] Dialects of Persian are sporadically spoken throughout the region from China to Syria to Russia, though mainly in the Iranian Plateau.

Literature

The literature of Iran is one of the world's oldest and most celebrated literatures, spanning over 2500 years from the many Achaemenid inscriptions, such as the Behistun inscription, to the celebrated Iranian poets of the Islamic Golden Age and Modern Iran.[12][13][14] Iranian literature has been described as one of the great literature's of humanity and one of the four main bodies of world literature.[15][16] Distinguished Professor L.P. Elwell-Sutton described the literature of the Persian language as "one of the richest poetic literatures of the world".[17]

Very few literary works of Pre-Islamic Iran have survived, due partly to the destruction of the libraries of Persepolis by Alexander of Macedon during the era of the Achaemenids and subsequent invasion of Iran by the Arabs in 641, who sought to eradicate all non-Quranic texts.[18] This resulted in all Iranian libraries being destroyed, books either being burnt or thrown into rivers. The only way that Iranians could protect these books was to bury them but many of the texts were forgotten over time.[18] However, excavations of the hidden books indicated the Iranian love and passion for books and libraries, the Arabs couldn't suppress this Iranian zeal. As soon as circumstances permitted, the Iranians wrote books and assembled libraries.[18]

Iranian literature encompasses a variety of literature in the languages used in Iran. Modern Iranian literature includes Persian literature, Azerbaijani literature, Kurdish literature and the literature of the remaining minority languages. Persian is the predominant and official language of Iran and throughout Iran's history, it has been the nation's most influential literary language. The Persian language has been often dubbed as the most worthy language of the world to serve as a conduit for poetry.[19] Azerbaijani literature has also had a profound effect on Iran's literature with it being developed highly after Iran's first reunification in 800 years under the Safavid Empire, whose rulers themselves wrote poetry.[20] There remain a few literary works of the extinct Iranian language of Old Azeri that was used in Azerbaijan prior to the linguistic Turkification of the people of the region.[21] Kurdish literature has also had a profound impact on the literature of Iran with it incorporating the various Kurdish dialects that are spoken throughout the Middle East. The earliest works of Kurdish literature are those of the 16th-century poet Malaye Jaziri.[22]

Some notable greats of Iranian poetry which have had major global influence include the likes of Ferdowsi, Sa'di, Hafiz, Attar, Nezami, Rumi and Omar Khayyam.[23][24] These poets have inspired the likes of Goethe, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and many others.

Contemporary Iranian literature has been influenced by classical Persian poetry, but also reflects the particularities of modern-day Iran, through writers such as Houshang Moradi-Kermani, the most translated modern Iranian author, and poet Ahmad Shamlou.[25]

Music

Iranian music has directly influenced the cultures of West Asia, Central Asia, Europe and South Asia.[26] It has mainly influenced and built up much of the musical terminology of the neighboring Turkic and Arabic cultures, and reached India through the 16th-century Persianate Mughal Empire, whose court promoted new musical forms by bringing Iranian musicians.[26]

Iran is the place of origin of complex instruments, with the instruments dating back to the third millennium BC.[27] A number of trumpets made of silver, gold, and copper were found in eastern Iran that are attributed to the Oxus civilization and date back between 2200 and 1750 BC. The use of both vertical and horizontal angular harps have been documented at the archaeological sites of Madaktu (650 BC) and Kul-e Fara (900–600 BC), with the largest collection of Elamite instruments documented at Kul-e Fara. Multiple depictions of horizontal harps were also sculpted in Assyrian palaces, dating back between 865 and 650 BC.[27]

The reign of Sassanian ruler Khosrow II is regarded as a "golden age" for Iranian music. Sassanid music is where many the many music cultures of the world trace their distant origins to. The court of Khosrow II hosted a number of prominent musicians, including Azad, Bamshad, Barbad, Nagisa, Ramtin, and Sarkash. Among these attested names, Barbad is remembered in many documents and has been named as remarkably high skilled. He was a poet-musician who developed modal music, may have invented the lute and the musical tradition that was to transform into the forms of dastgah and maqam.[27][28][29] He has been credited to have organized a musical system consisting of seven "royal modes" (xosrovāni), 30 derived modes (navā), and 360 melodies (dāstān).[27][28]

The academic classical music of Iran, in addition to preserving melody types that are often attributed to Sassanian musicians, is based on the theories of sonic aesthetics as expounded by the likes of Iranian musical theorists in the early centuries of after the Muslim conquest of the Sasanian Empire, most notably Avicenna, Farabi, Qotb-ed-Din Shirazi, and Safi-ed-Din Urmawi.[26]

Dance

Iran has a rich and ancient dance culture which extends to the sixth millennium BC. Dances from ancient artifacts, excavated at the archaeological pre-historic sites of Iran, portray a vibrant culture that mixes different forms of dances for all occasions. In conjunction with music, the artifacts depicted actors, dancers and ordinary people dancing in plays, dramas, celebrations, mourning and religious rituals with equipment such as costumes of animals or plants, masks and surrounding objects. As time progressed, this culture of dance began to develop and flourish.[30]

Iran is a multi-ethnic nation. Although the cultures of its ethnic groups are very similar and in most areas near identical, each has their own distinct and specific dance style. Iran possesses four categories of dance with these being: group dances, solo improvisational dance, war or combat dances and spiritual dances.

Typically, the group dances are often unique and named after the region or the ethnic groups with which they are associated with. These dances can be chain dances involving a group or the more common group dances mainly performed at festive occasions like weddings and Noruz celebrations which focus less on communal line or circle dances and more on solo improvisational forms, with each dancer interpreting the music in her own special way but within a specific range of dance vocabulary sometimes blending other dance styles or elements.[31]

Solo dances are usually reconstructions of the historical and court dances of the various Iranian dynasties throughout history, with the most common types being that of the Safavid and Qajar dynasties due to them being relatively newer.[31] These often are improvisational dances and utilize delicate, graceful movements of the hands and arms, such as wrist circles.[31]

War or Combat dances, imitate combat or help to train the warrior. It could be argued that men from the Zurkhaneh ("House of Strength") and their ritualized, wrestling-training movements are known as a type of dance called "Raghs-e-Pa" with the dances and actions done in the Zurkhaneh also resembling that of a martial art.[31][32]

Spiritual dances in Iran are known as "sama". There are various types of these spiritual dances which are used for spiritual purposes such as ridding the body of ill omens and evil spirits. These dances involve trance, music and complex movements. An example of such dance is that of the Balochi's called "le’b gowati", which is performed to rid a supposedly possessed person of the possessing spirit. In the Balochi language, the term "gowati" refers to psychologically ill patients who have recovered through music and dance.[33][34]

The earliest researched dances from Iran is a dance worshiping Mithra, the Zoroastrian angelic divinity of covenant, light, and oath, which was used commonly by the Roman Cult of Mithra.[35] One of the cult's ceremonies involved the sacrifice of a bull followed by a dance that promoted vigor in life.[35] The Cult of Mithra were active from the 1st Century CE to the 4th Century CE and worshiped a mystery religion inspired by the Iranian worship of Mithra. It was a rival of Christianity in the Roman Empire and was eventually suppressed in the 4th Century CE by Roman authorities in favor of Christianity.[36][37][38] This was done in order to counter the greater Iranian cultural influence that was expanding throughout the Roman empire.[37] The cult was highly adhered and respected throughout the Roman Empire with it center in Rome, and was popular throughout the western half of the empire, as far south as Roman Africa and Numidia, as far north as Roman Britain, and to a lesser extent in Roman Syria in the east.[39][40]

Architecture

The history of Iranian architecture dates back to at least 5,000 BC with characteristic examples distributed over a vast area from Turkey and Iraq to Uzbekistan and Tajikistan to the South Caucasus and Zanzibar. Currently, there are 19 UNESCO designated World Heritage Sites that were designed and constructed by Iranians, with 11 of them being located outside of Iran. Iranian architecture displays a great variety of both structure and aesthetics and despite the repeated trauma of destructive invasions and cultural shocks, the Iranian zeal and identity has always triumphed and flourished. In turn, it has greatly influenced the architecture of its invaders from the Greeks to the Arabs to the Turks.[41][42]

The traditional theme of Iranian architecture is cosmic symbolism, which depicts the communication and participation of man with the powers of heaven. This theme has not only given continuity and longevity to the architecture of Iran, but has been a primary source of its emotional character of the nation as well. Iranian architecture ranges from simple structures to "some of the most majestic structures the world has ever seen".[42][43]

Iranian architectural style is the combination of intensity and simplicity to form immediacy, while ornament and, often, subtle proportions reward sustained observation. Iranian architecture makes use of abundant symbolic geometry, using pure forms such as the circle and square, and plans are based on often symmetrical layouts featuring rectangular courtyards and halls. The paramount virtues of Iranian architecture are: "a marked feeling for form and scale; structural inventiveness, especially in vault and dome construction; a genius for decoration with a freedom and success not rivaled in any other architecture".[44]

The traditional architecture of Iran throughout the ages is categorized into 2 families and six following classes or styles. The two categories are Zoroastrian and Islamic, which references the eras of Pre-Islamic and Post-Islamic Iran, and the six styles, in order of their era, are: Parsian, Parthian Khorasani, Razi, Azari, Esfahani. The pre-Islamic styles draw on 3000 to 4000 years of architectural development from the various civilizations of the Iranian plateau. The post-Islamic architecture of Iran in turn, draws ideas from its pre-Islamic predecessor, and has geometrical and repetitive forms, as well as surfaces that are richly decorated with glazed tiles, carved stucco, patterned brickwork, floral motifs, and calligraphy.[45]

In addition to historic gates, palaces, bridges, buildings and religious sites which highlight the highly developed supremacy of the Iranian art of architecture, Iranian gardens are also an example of Iran's comic symbolism and unique style of combining intensity and simplicity for form immediacy.[41][43] There are currently 14 Iranian gardens that are listed as UNESCO World Heritage Sites, with 5 of them being located outside of Iran.[46] The traditional style of Iranian gardens are to represent an earthly paradise or a heaven on Earth. From the time of the Achaemenid Empire, the idea of an earthly paradise spread through Iranian literature to other cultures, with the word for paradise in the Iranian languages of Avestan, Old Persian and Median, spreading to languages across the world.[47] The style and design of the Iranian garden greatly influenced the garden styles of countries from Spain to Italy and Greece to India, with some notable examples of such gardens being the gardens of the Alhambra in Spain, Humayun's Tomb and the Taj Mahal in India, the Hellenistic gardens of the Seleucid Empire and the Ptolemies in Alexandria.[47]

Religion in Iran

Zoroastrianism was the national faith of Iran for more than a millennium before the Arab conquest. It has had an immense influence on Iranian philosophy, culture and art after the people of Iran converted to Islam.[48]

Today of the 98% of Muslims living in Iran, around 89% are Shi'a and only around 9% are Sunni. This is quite the opposite trend of the percentage distribution of Shi'a to Sunni Islam followers in the rest of the Muslim population from state to state (primarily in the Middle East) and throughout the rest of the world.

Followers of the Baha'i faith form the largest non-Muslim minority in Iran. Followers of the Baha'i faith are scattered throughout small communities in Iran, although there seems to be a large population of people who follow the Baha'i faith in Tehran. The Baha'i are severely persecuted by the Iranian government.

Followers of the Christian faith consist of around 250,000 Armenians, around 32,000 Assyrians, and a small number of Roman Catholic, Anglican, and Protestant Iranians that have been converted by missionaries in earlier centuries. Thus, Christians that live in Iran are primarily descendants of indigenous Christians that were converted during the 19th and 20th centuries. Judaism is an officially recognized faith in Iran, and in spite of the hostilities between Iran and Israel over the Palestinian issue, the millennia-old Jewish community in Iran enjoys the right to practice their religion freely as well as a dedicated seat in parliament to a representative member of their faith. In addition to Christianity and Judaism, Zoroastrianism is another officially recognized religion in Iran, although followers of this faith do not hold a large population in Iran. In addition, although there have been isolated incidences of prejudice against Zoroastrians, most followers of this faith have not been persecuted for being followers of this faith.[49]

Holidays in Iran

The Persian year begins in the vernal equinox: if the astronomical vernal equinox comes before noon, then the present day is the first day of the Persian year. If the equinox falls after noon, then the next day is the official first day of the Persian year. The Persian Calendar, which is the official calendar of Iran, is a solar calendar with a starting point that is the same as the Islamic calendar. According to the Iran Labor Code, Friday is the weekly day of rest. Government official working hours are from Saturday to Wednesday (from 8 am to 4 pm).[50]

Although the date of certain holidays in Iran are not exact (due to the calendar system they use, most of these holidays are around the same time), some of the major public holidays in Iran include Oil Nationalization Day (20 March), Nowrooz—which is the Iranian equivalent of New Years (20 March), the Prophet's Birthday and Imam Sadeq (4 June), and the Death of Imam Khomeini (5 June). Additional holidays include The Anniversary of the Uprising Against the Shah (30 January), Ashoura (11 February), Victory of the 1979 Islamic Revolution (20 January), Sizdah-Bedar—Public Outing Day to end Nowrooz (1 April), and Islamic Republic Day (2 April).

Wedding ceremonies

There are two stages in a typical wedding ritual in Iran. Usually, both phases take place in one day. The first stage is known as "Aghd", which is basically the legal component of marriage in Iran. In this process, the bride and groom, as well as their respective guardians, sign a marriage contract. This phase usually takes place in the bride's home. After this legal process is over, the second phase, "Jashn-e Aroosi" takes place. In this step, which is basically the wedding reception, where actual feasts and celebrations are held, typically lasts from about 3–7 days. The ceremony takes place in a decorated room with flowers and a beautifully decorated spread on the floor. This spread is typically passed down from mother to daughter and is composed of very nice fabric such as "Termeh" (cashmere), "Atlas" (gold embroidered satin), or "Abrisham" (silk).

Items are placed on this spread: a Mirror (of fate), two Candelabras (representing the bride and groom and their bright future), a tray of seven multi-colored herbs and spices (including poppy seeds, wild rice, angelica, salt, nigella seeds, black tea, and frankincense). These herbs and spices play specific roles ranging from breaking spells and witchcraft, to blinding the evil eye, to burning evil spirits. In addition to these herbs/spices, a special baked and decorated flatbread, a basket of decorated eggs, decorated almonds, walnuts and hazelnuts (in their shell to represent fertility), a basket of pomegranates/apples (for a joyous future as these fruits are considered divine), a cup of rose water (from special Persian roses)—which helps perfume the air, a bowl made out of sugar (apparently to sweeten life for the newlywed couple), and a brazier holding burning coals and sprinkled with wild rue (as a way to keep the evil eye away and to purify the wedding ritual) are placed on the spread as well. Finally, there are additional items that must be placed on the spread, including a bowl of gold coins (to represent wealth and prosperity), a scarf/shawl made of silk/fine fabric (to be held over the bride and groom's head at certain points in the ceremony), two sugar cones—which are ground above the bride and groom's head, thus symbolizing sweetness/happiness, a cup of honey (to sweeten life), a needle and seven strands of colored thread (the shawl that is held above the bride and groom's head is sewn together with the string throughout the ceremony), and a copy of the couple's Holy Book (other religions require different texts); but all of these books symbolize God's blessing for the couple.[51] An early age in marriage—especially for brides—is a long documented feature of marriage in Iran. While the people of Iran have been trying to legally change this practice by implementing a higher minimum in marriage, there have been countless blocks to such an attempt. Although the average age of women being married has increased by about five years in the past couple decades, young girls being married is still common feature of marriage in Iran—even though there is an article in the Iranian Civil Code that forbid the marriage of women younger than 15 years of age and males younger than 18 years of age.[52]

Persian rugs

In Iran, Persian rugs have always been a vital part of the Persian culture.

Iranians were some of the first people in history to weave carpets. First deriving from the notion of basic need, the Persian rug started out as a simple/pure weave of fabric that helped nomadic people living in ancient Iran stay warm from the cold, damp ground. As time progressed, the complexity and beauty of rugs increased to a point where rugs are now bought as decorative pieces.[53] Because of the long history of fine silk and wool rug weaving in Iran, Persian rugs are world-renowned as some of the most beautiful, intricately designed rugs available. Around various places in Iran, rugs seem to be some of the most prized possessions of the local people. Iran currently produces more rugs and carpets than all other countries in the world put together.[54]

Modern culture

Cinema

With 300 international awards in the past 10 years, Iranian films continue to be celebrated worldwide. The best known Persian directors are Abbas Kiarostami, Majid Majidi, Jafar Panahi and Asghar Farhadi.

Contemporary art

There is a resurgence of interest in Iranian contemporary artists and in artists from the larger Iranian diaspora. Key notables include Shirin Aliabadi, Mohammed Ehsai, Ramin Haerizadeh, Rokni Haerizadeh, Golnaz Fathi, Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, Parastou Forouhar, Pouran Jinchi, Farhad Moshiri, Shirin Neshat, Parviz Tanavoli, Y. Z. Kami, and Charles Hossein Zenderoudi.[55]

Music

Architecture

Cuisine

Cuisine in Iran is considered to be one of the most ancient forms of cuisine around the world. Bread is arguably the most important food in Iran, with a large variety of different bread, some of the most popular of which include: nan and hamir, which are baked in large clay ovens (also called "tenurs"). In Iranian cuisine, there are many dishes that are made from dairy products. One of the most popular of which includes yoghurt ("mast")—which has a specific fermentation process that is widely put to use amongst most Iranians. In addition, mast is used to make soup and is vital in the production of oil. In addition to these dairy products, Iranian cuisine involves a lot of dishes cooked from rice. Some popular rice dishes include boiled rice with a variety of ingredients such as meats, vegetables, and seasonings ("plov") including dishes like chelo-horesh, shish kebab with rice, chelo-kebab, rice with lamb, meatballs with rice, and kofte (plain boiled rice). In addition, Iranian cuisine is famous for its sweets. One of the most famous of which includes "baklava" with almonds, cardamom, and egg yolks. Iranian sweets typically involve the use of honey, cinnamon, lime juice, and sprouted wheat grain. One very popular dessert drink in Iran, "sherbet sharbat-portagal", is made from a mixture of orange peel and orange juice boiled in thin sugar syrup and diluted with rose water. Just like the people of many Middle Eastern countries the most preferred drink of the people of Iran is tea (without milk) or "kakhve-khana".[56]

Sports

- The game of Polo originated with Iranian tribes in ancient times and was regularly seen throughout the country until the revolution of 1979 where it became associated with the monarchy. It continues to be played, but only in rural areas and discreetly. Recently, as of 2005, it has been acquiring an increasingly higher profile. In March 2006, there was a highly publicised tournament and all significant matches are now televised.

- The Iranian Zoor Khaneh

Women in Persian culture

Since the 1979 Revolution, Iranian women have had more opportunities in some areas and more restrictions in others. One of the striking features of the Revolution was the large scale participation of women from traditional backgrounds in demonstrations leading up to the overthrow of the monarchy. The Iranian women who had gained confidence and higher education during the Pahlavi era participated in demonstrations against the Shah to topple the monarchy. The culture of education for women was established by the time of revolution so that even after the revolution, large numbers of women entered civil service and higher education,[57] and in 1996 fourteen women were elected to the Islamic Consultative Assembly. In 2003, Iran's first woman judge during the Pahlavi era, Shirin Ebadi, won the Nobel Peace Prize for her efforts in promoting human rights.

According to a UNESCO world survey, at the primary level of enrollment Iran has the highest female to male ratio in the world among sovereign nations, with a female to male ratio of 1.22 : 1.00.[58] By 1999, Iran had 140 female publishers, enough to hold an exhibition of books and magazines published by women.[59] As of 2005, 65% of Iran's university students and 43% of its salaried workers were women.[60] and as of early 2007 nearly 70% of Iran's science and engineering students are women.[61] This has led to many female school and university graduates being under-utilized. This is beginning to have an effect on Iranian society and was a contributing factor to protests by Iranian youth.

During recent decades, Iranian women have had significant presence in Iran's scientific movement, art movement, literary new wave and contemporary Iranian cinema. Women account for 60% of all students in the natural sciences, including one in five PhD students.[62]

Traditional holidays/celebrations

Iranians celebrate the following days based on a solar calendar, in addition to important religious days of Islamic and Shia calendars, which are based on a lunar calendar.

- Nowruz (Iranian New Year) - Starts from 21 March

- Sizdah be dar (Nature Day)

- Jashn-e-Tirgan (Water Festival)

- Jashn-e-Sadeh (Fire Festival)

- Jashn-e-Mehregan (Autumn Festival)

- Shab-e-Yalda (Winter Feast)

- Charshanbeh Suri

Traditional cultural inheritors of the old Persia

Like the Persian carpet that exhibits numerous colors and forms in a dazzling display of warmth and creativity, Persian culture is the glue that bonds the peoples of western and central Asia. The South Caucasus and Central Asia "occupy an important place in the historical geography of Persian civilization.” Much of the region was included in the Pre-Islamic Persian empires, and many of its ancient peoples either belonged to the Iranian branch of the Indo-European peoples (e.g. Medes and Soghdians), or were in close cultural contact with them (e.g. the Armenians).[63] In the words of Iranologist Richard Nelson Frye:

- Many times I have emphasized that the present peoples of central Asia, whether Iranian or Turkic speaking, have one culture, one religion, one set of social values and traditions with only language separating them.

The Culture of Persia has thus developed over several thousand years. But historically, the peoples of what are now Iran, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Turkey, Georgia, and Afghanistan are related to one another as part of the larger group of peoples of the Greater Iranian cultural and historical sphere. The Northern Caucasus is well within the sphere of influence of Persian culture as well, as can be seen from the many remaining relics, ruins, and works of literature from that region.(e.g. 1) (e.g. 2)

Iran is filled with tombs of poets and musicians, such as this one belonging to Rahi Mo'ayeri. An illustration of Iran's deep artistic heritage.

Iran is filled with tombs of poets and musicians, such as this one belonging to Rahi Mo'ayeri. An illustration of Iran's deep artistic heritage.

Craftsmanship in Iranian Architecture. An excellent animation depicting the intricate details of the traditional interior design: (click).

Craftsmanship in Iranian Architecture. An excellent animation depicting the intricate details of the traditional interior design: (click). An ancient ice house, called a yakhchal, built in ancient times for storing ice during summers.

An ancient ice house, called a yakhchal, built in ancient times for storing ice during summers.

Contributions to humanity in ancient history

From the humble brick, to the windmill, Persians have mixed creativity with art and offered the world numerous contributions.[64][65] What follows is a list of just a few examples of the cultural contributions of Greater Iran.

- (10,000 BC) - Earliest known domestication of the goat.[66][67][68][69]

- (6000 BC) - The modern brick.[70] Some of the oldest bricks found to date are Persian, from c. 6000 BC.

- (5000 BC) - Invention of wine. Discovery made by University of Pennsylvania excavations at Hajji Firuz Tepe in northwestern Iran.[71]

- (5000 BC) - Invention of the Tar (lute), which led to the development of the guitar.[72][73]

- (3000 BC) - The ziggurat. The Sialk ziggurat, according to the Cultural Heritage Organization of Iran, predates that of Ur or any other of Mesopotamia's 34 ziggurats.

- (3000 BC) - A game resembling backgammon appears in the east of Iran.[74]

- (1400 BC - 600 BC) - Zoroastrianism: where the first prophet of a monotheistic faith arose according to some scholars,[75] claiming Zoroastrianism as being "the oldest of the revealed credal religions, which has probably had more influence on mankind directly or indirectly, more than any other faith".[76][77]

- (576 BC - 529 BC) - The Cyrus Cylinder: The world's first charter of human rights.[78]

- (521 BC) - The game of Polo.[79]

- (500 BC) - First Banking System of the World, at the time of the Achaemenid, establishment of Governmental Banks to help farmers at the time of drought, floods, and other natural disasters in form of loans and forgiveness loans to restart their farms and husbandries. These Governmental Banks were effective in different forms until the end of Sassanian Empire before invasion of Arabs to Persia.

- (500 BC) - The word Check has a Persian root in old Persian language. The use of this document as a check was in use from Achaemenid time to the end of Sassanian Empire. The word of [Bonchaq, or Bonchagh] in modern Persian language is new version of old Avestan and Pahlavi language "Check". In Persian it means a document which resembles money value for gold, silver and property. By law people were able to buy and sell these documents or exchange them.

- (500 BC) - World's oldest staple.

- (500 BC) - The first taxation system (under the Achaemenid Empire).

- (500 BC) - "Royal Road" - the first courier post.[80]

- (500 BC) - Source for introduction of the domesticated chicken into Europe.

- (500 BC) - First cultivation of spinach.

- (400 BC) - Yakhchals, ancient refrigerators. (See picture above)

- (400 BC) - Ice cream.[81]

- (250 BC) - Original excavation of a Suez Canal, begun under Darius, completed under the Ptolemies.[82]

- (50 AD) - Peaches, a fruit of Chinese origin, were introduced to the west through Persia, as indicated by their Latin scientific name, Prunus persica, from which (by way of the French) we have the English word "peach."[83]

- (271 AD) - Academy of Gundishapur - The first hospital.[84]

- (700 AD) - The cookie.

- (700 AD) - The windmill.[85]

- (864 AD - 930 AD) - First systematic use of alcohol in Medicine: Rhazes.[86]

- (1000 AD) - Tulips were first cultivated in medieval Persia.[87]

- (1000 AD) - Introduction of paper to the west.[88]

- (935 AD - 1020 AD) - Ferdowsi writes the Shahnama (Book of Kings) that resulted in the revival of Iranian culture and the expansion of the Iranian cultural sphere.

- (980 AD - 1037 AD) - Avicenna, a physician, writes The Canon of Medicine one of the foundational manuals in the history of modern medicine.

- (1048 AD - 1131 AD) - Khayyam, one of the greatest polymaths of all time, presents a theory of heliocentricity to his peers. His contributions to laying the foundations of algebra are also noteworthy.

- (1207 AD - 1273 AD) - Rumi writes poetry and in 1997, the translations were best-sellers in the United States.[89]

- Algebra and Trigonometry: Numerous Iranians were directly responsible for the establishment of Algebra, the advancement of Medicine and Chemistry, and the discovery of Trigonometry.[90]

- Qanat, subterranean aqueducts.

- Wind catchers, ancient air residential conditioning.

See also

- Iranian Cultural Heritage Organization (ICHO)

- International Rankings of Iran in Culture

- Encyclopædia Iranica (30-volume encyclopaedia of Iran's culture; edited and published by Columbia University & funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities)

- Higher education in Iran

- Cinema of Iran

- Iranian calendar

- Iranian continent

- Iranian Studies

- Taarof

- Qahr and Ashti

- Media of Iran

- Museums in Iran

- Persian cuisine

- Persian theatre

- Persian names

- Persian women

- Persianate

- Persianization

- Persophilia, the admiration of Iranians and their culture

- Taarof (Persian form of civility emphasizing both deference and social rank)

References

- Oelze, Sabine (13 April 2017). "How Iran became a cradle of civilization". DW. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- Bakhtiyar, Afshin (2014). Iran the Cradle of Civilization. Gooya House of Cultural Art. ISBN 978-9647610032.

- "Iran – Cradle of Civilisation". Drents Museum. 12 April 2018. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- Kermanshah, A Cradle of Civilization, September 28, 2007. Retrieved 4 July 2019

- "Persian Influence on Greek Culture". Livius.org. 7 November 2018. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- Milani, A. Lost Wisdom. 2004.ISBN 0-934211-90-6 p.15

- Greater Iran, Mazda Publishers, 2005. ISBN 1568591772 xi

- "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". Cia.gov. Archived from the original on 2012-02-03. Retrieved 2019-07-01

- Windfuhr, Gernot. The Iranian Languages. Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group.

- "Ethnologue report for Iranian". Ethnologue.com.

- Eberhard, David M., Gary F. Simons, and Charles D. Fennig (eds.). 2019. Ethnologue: Languages of the World. Twenty-second edition. Dallas, Texas: SIL International. Online version: http://www.ethnologue.com.

- Spooner, Brian (1994). "Dari, Farsi, and Tojiki". In Marashi, Mehdi (ed.). Persian Studies in North America: Studies in Honor of Mohammad Ali Jazayery. Leiden: Brill. pp. 177–178.

- Spooner, Brian (2012). "Dari, Farsi, and Tojiki". In Schiffman, Harold (ed.). Language policy and language conflict in Afghanistan and its neighbors: the changing politics of language choice. Leiden: Brill. p. 94.

- Campbell, George L.; King, Gareth, eds. (2013). "Persian". Compendium of the World's Languages (3rd ed.). Routledge. p. 1339.

- Arberry, Arthur John (1953). The Legacy of Persia. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 200. ISBN 0-19-821905-9.

- Von David Levinson; Karen Christensen, Encyclopedia of Modern Asia, Charles Scribner's Sons. 2002, vol. 4, p. 480

- Elwell-Sutton, L.P. (trans.), In search of Omar Khayam by Ali Dashti, Columbia University Press, 1971, ISBN 0-231-03188-2

- Kent, Allen; Lancour, Harold; Daily, Jay E. (1975). Encyclopedia of Library and Information Science: Volume 13. pp. 23, 24. ISBN 9780824720131.

- Emmerick, Ronald Eric (23 February 2016). "Iranian languages". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- Doerfer, Gerhard (15 December 1991). "CHAGHATAY LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- Yarshater, E. (15 December 1988). "AZERBAIJAN vii. The Iranian Language of Azerbaijan". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- Kreyenbroek, Philip G. (20 July 2005). "KURDISH WRITTEN LITERATURE". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 1 July 2019

- C. A. (Charles Ambrose) Storey and Franço de Blois (2004), "Persian Literature - A Biobibliographical Survey: Volume V Poetry of the Pre-Mongol Period", RoutledgeCurzon; 2nd revised edition (June 21, 2004). p. 363: "Nizami Ganja’i, whose personal name was Ilyas, is the most celebrated native poet of the Persians after Firdausi. His nisbah designates him as a native of Ganja (Elizavetpol, Kirovabad) in Azerbaijan, then still a country with an Iranian population, and he spent the whole of his life in Transcaucasia; the verse in some of his poetic works which makes him a native of the hinterland of Qom is a spurious interpolation."

- Franklin Lewis, Rumi Past and Present, East and West, Oneworld Publications, 2000. How is it that a Persian boy born almost eight hundred years ago in Khorasan, the northeastern province of greater Iran, in a region that we identify today as Central Asia, but was considered in those days as part of the Greater Persian cultural sphere, wound up in Central Anatolia on the receding edge of the Byzantine cultural sphere, in which is now Turkey, some 1500 miles to the west? (p. 9)

- HOUSHMAND, Zara, "Iran", in Literature from the "Axis of Evil" (a Words Without Borders anthology), ISBN 978-1-59558-205-8, 2006, pp.1-3

- "IRAN xi. MUSIC". Encyclopædia Iranica. 30 March 2012. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- Lawergren, Bo (20 February 2009). "MUSIC HISTORY i. Pre-Islamic Iran". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- "BĀRBAD". Encyclopædia Iranica. III. December 15, 1988. pp. 757–758.

- ČAKĀVAK, Encyclopædia Iranica. IV. December 15, 1990. pp. 649–650.

(Pers. navā, Ar. laḥn, naḡma, etc.)

- Taheri, Sadreddin (2012). "Dance, Play, Drama; a Survey of Dramatic Actions in Pre-Islamic Artifacts of Iran". Honarhay-e Ziba. Tehran, Iran.

- Laurel Victoria, Gray (2007). "A Brief Introduction to Persian Dance". Central Asian, Persian, Turkic, Arabian and Silk Road Dance Culture. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- Nashepour, Peyman. "A brief about Persian dance". Official Website of Dr. Peyman Nasehpour. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- Friend, Robyn C. (2002). "Spirituality in Iranian Music and Dance Conversations with Morteza Varzi". The Best of Habibi, A Journal for Lovers of Middle Eastern Dance and Arts. 18. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- Oakling (May 2, 2003). "Bandari". everything2. Retrieved 3 July 2019

- Kiann, Nima (2000). "Persian Dance and It's Forgotten History". Les Ballets Persans. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- Hopfe, Lewis M. (1 September 1994). Uncovering Ancient Stones. US. pp. 147. ISBN 9780931464737.

Today more than four hundred locations of Mithraic worship have been identified in every area of the Roman Empire. Mithraea have been found as far west as Britain and as far east as Dura Europas. Between the second and fourth centuries C.E. Mithraism may have vied with Christianity for domination of the Roman world.

- Hopfe, Lewis M.; Richardson, Henry Neil (September 1994). "Archaeological Indications on the Origins of Roman Mithraism".

- Martin, Luther H.; Beck, Roger (December 30, 2004). "Foreword". Beck on Mithraism: Collected Works With New Essays. Ashgate Publishing. pp. xiii. ISBN 978-0-7546-4081-3.

However, the cult was vigorously opposed by Christian polemicists, especially by Justin and Tertullian, because of perceived similarities between it and early Christianity. And with the anti-pagan decrees of the Christian emperor Theodosius during the final decade of the fourth century, Mithraism disappeared from the history of religions as a viable religious practice.

- Lewis M. Hopfe, "Archaeological indications on the origins of Roman Mithraism", in Lewis M. Hopfe (ed). Uncovering ancient stones: essays in memory of H. Neil Richardson, Eisenbrauns (1994), pp. 147–158. p. 156: "Beyond these three Mithraea [in Syria and Palestine], there are only a handful of objects from Syria that may be identified with Mithraism. Archaeological evidence of Mithraism in Syria is therefore in marked contrast to the abundance of Mithraea and materials that have been located in the rest of the Roman Empire. Both the frequency and the quality of Mithraic materials is greater in the rest of the empire. Even on the western frontier in Britain, archaeology has produced rich Mithraic materials, such as those found at Walbrook. If one accepts Cumont’s theory that Mithraism began in Iran, moved west through Babylon to Asia Minor, and then to Rome, one would expect that the cult left its traces in those locations. Instead, archaeology indicates that Roman Mithraism had its epicenter in Rome. Wherever its ultimate place of origin may have been, the fully developed religion known as Mithraism seems to have begun in Rome and been carried to Syria by soldiers and merchants. None of the Mithraic materials or temples in Roman Syria except the Commagene sculpture bears any date earlier than the late first or early second century. [footnote in cited text: 30. Mithras, identified with a Phrygian cap and the nimbus about his head, is depicted in colossal statuary erected by King Antiochus I of Commagene, 69–34 BCE. (see Vermaseren, CIMRM 1.53–56). However, there are no other literary or archaeological evidences to indicate that the religion of Mithras as it was known among the Romans in the second to fourth centuries AD was practiced in Commagene]. While little can be proved from silence, it seems that the relative lack of archaeological evidence from Roman Syria would argue against the traditional theories for the origins of Mithraism."

- Clauss, M., The Roman cult of Mithras, pages 26 and 27

- Arthur Upham Pope. Introducing Persian Architecture. Oxford University Press. London. 1971.

- Arthur Upham Pope. Persian Architecture. George Braziller, New York, 1965. p.266

- Nader Ardalan and Laleh Bakhtiar. Sense of Unity; The Sufi Tradition in Persian Architecture. 2000. ISBN 1-871031-78-8

- Arthur Upham Pope. Persian Architecture. George Braziller, New York, 1965. p.10

- Sabk Shenasi Mi'mari Irani (Study of styles in Iranian architecture), M. Karim Pirnia. 2005. ISBN 964-96113-2-0

- https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1372 "The Persian Garden" (1372) at World Heritage Site website

- Fakour M., Achaemenid Gardens [1]; CAIS-Online - Accessed 4 July 2019

- Shaul Shaked, From Zoroastrian Iran to Islam, 1995; and Henry Corbin, En Islam Iranien: Aspects spirituels et philosophiques (4 vols.), Gallimard, 1971-3.

- "Iran Index of Religion". About.com.

- "Iran Holidays 2013". Q++ Studio.

- "Persian Wedding Traditions and Customs". Farsinet.com.

- Momeni, Djamehid (August 1972). "The Difficulties of Changing the Age at Marriage in Iran". Journal of Marriage and Family. 34 (3): 545–551. doi:10.2307/350454. JSTOR 350454.

- Opie, James (1981). Tribal Rugs of Southern Persia. Portland, OR. p. 47.

- "Persian Rugs, Persian Carpets, and Oriental Rugs". Farsinet.com.

- Esman, Abigail R. (10 January 2011). "Forbes: Why Today's Iranian Art is One of your best investments".

- "Iranian National Cuisine". The Great Silk Road. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011.

- "Adult education offers new opportunities and options to Iranian women". Ungei.org. 6 March 2006. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

- "Girls to boys ratio, primary level enrolment statistics - countries compared". NationMaster. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

- The Last Great Revolution by Robin Wright c2000, p.137

- Ebadi, Shirin, Iran Awakening : A Memoir of Revolution and Hope by Shirin Ebadi with Azadeh Moaveni, Random House, 2006 (p.210)

- Masood, Ehsan (2 November 2006). "Islam and Science: An Islamist revolution". Nature. 444 (7115): 22–25. Bibcode:2006Natur.444...22M. doi:10.1038/444022a. PMID 17080057. S2CID 2967719.

- Koenig, R. (2000). "Iranian Women Hear the Call of Science". Science. sciencemag.org. 290 (5496): 1485. doi:10.1126/science.290.5496.1485. PMID 17771221. Retrieved 13 January 2016.

- Edmund Herzing, Iran and the former Soviet South, The Royal Institute of International Affairs, 1995, ISBN 1-899658-04-1 p.48

- Iran's contribution to the world civilization. A.H. Nayer-Nouri. 1969. Tehran, General Dept. of Publications, Ministry of Culture and Arts. OCLC number: 29858074 Perry–Castañeda Library Reprinted in 1996 under the title: سهم ارزشمند ایران در فرهنگ جهان

- "The effect of Persia's culture and civilization on the world" (Taʼ̲sīr-i farhang va tamaddun-i Īrān dar jahān). Abbās Qadiyānī (عباس قدياني). Tehran. 2005. Intishārāt-i Farhang-i Maktūb. ISBN 964-94224-4-7 OCLC 70237532

- Zeder, M.A. (2001). "A metrical analysis of a collection of modern goats (Capra hircus aegargus and c.h. hircus) from Iran and Iraq: Implications for the study of caprine domestication". Journal of Archaeological Science. 28: 61–79. doi:10.1006/jasc.1999.0555. S2CID 11815276.

- Zeder, M.A. (2008). "Domestication and early agriculture in the Mediterranean Basin: Origins, diffusuion, and impact". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (33): 11597–11640. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10511597Z. doi:10.1073/pnas.0801317105. PMC 2575338. PMID 18697943.

- Zeder, M.A.; Hesse, B. (2000). "The initial domestication of goats(capra hircus) in the Zagros mountains 10,000 years ago". Science. 287 (5461): 2254–2257. Bibcode:2000Sci...287.2254Z. doi:10.1126/science.287.5461.2254. PMID 10731145.

- MacHugh, D.E.; Bradley, D.G. (2001). "Livestock genetic origins : Goats buck the trend". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 98 (10): 5382–5384. Bibcode:2001PNAS...98.5382M. doi:10.1073/pnas.111163198. PMC 33220. PMID 11344280.

- Arthur Upham Pope, Persian Architecture, 1965, New York, p.15

- Link: University of Pennsylvania "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 16 December 2008. Retrieved 2009-07-31.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Cultural Sociology of the Middle East, Asia, and Africa: An Encyclopedia Volume 2. Stanton AL. p.166

- .Miller L. Music and Song in Persia (RLE Iran B): The Art of Avaz Routledge 2012 p.5-8

- Richard Foltz. Iran in World History. Oxford University Press. 2015

- Abbas Milani. Lost Wisdom. 2004. Mage Publishers. p.12. ISBN 0-934211-90-6

- Mary Boyce, "Zoroastrians", London, 1979, 1.

- Notes:

- Zoroastrianism had an important impact on Judaism, and thus indirectly, on Christianity and Islam.

- Zoroaster himself was not an ethnic Persian, but (possibly) an ethnic Bactrian who were closely related to Persians.

- Arthur Henry Robertson and J. G. Merrills, Human Rights in the World: An Introduction to the Study of the International, Political Science, Page 7, 1996; Paul Gordon Lauren, The Evolution of International Human Rights: Visions Seen, Political Science, Page 11, 2003; Xenophon and Larry Hedrick, Xenophon's Cyrus the Great: The Arts of Leadership and War, History, Page xiii, 2007

- Link: BBC http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/middle_east/4272210.stm

- Links:

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 7 September 2005. Retrieved 2007-03-05.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- http://www.infoplease.com/ce6/history/A0839873.html

- Links:

- Cotton candy.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2 June 2008. Retrieved 2005-02-01.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- http://www.mmdtkw.org/VAncientInventions.html

- Links:

- http://www.uh.edu/engines/epi1257.htm

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 7 September 2005. Retrieved 2007-03-05.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Link: http://www.birdnature.com/nov1899/peach.html

- Elgood, Cyril. A medical history of Persia, Cambridge University Press, 1951, p. 173

- Links:

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 15 January 2012. Retrieved 21 January 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Link: http://www.free-definition.com/Abu-Bakr-Mohammad-Ibn-Zakariya-al-Razi.html Archived 11 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Links:

- Link: "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 29 November 2013. Retrieved 11 April 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Refer to article by the Christian Science Monitor - http://www.csmonitor.com/1997/1125/112597.us.us.3.html.

- See:

- Hill, Donald. Islamic Science and Engineering. May 1994. Edinburgh University Press. p.10

- Sardar, Ziauddin. Introducing Mathematics. Totem Books. 1999.

Further reading

- Michael C. Hillman. Iranian Culture. 1990. University Press of America. ISBN 0-8191-7694-X

- Iran: At War with History, by John Limbert, pub. 1987, a book of socio-cultural customs of The Islamic Republic of Iran

- George Ghevarghese Joseph.The Crest of the Peacock: The Non-European Roots of Mathematics. July 2000. Princeton U Press.

- Welch, S.C. (1972). A king's book of kings: the Shah-nameh of Shah Tahmasp. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 9780870990281.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Culture of Iran. |

- Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance Of Iran Official Website

- Secretariat of The High Council of The Cultural Revolution

- Islamic Republic of Iran Physical Education Organization

- Islamic Republic of Iran Academy of The Arts

- Islamic Republic of Iran International Center for Dialogue Among Civilizations

- Culture of Iran - parstimes.com

- Culture of Iran

- Cultural Research Bureau of Iran

- Iran Institute for Humanities and Cultural Studies

- Iran a cultural profile

- The Culture of Iran

- Persian Language (Persian)

- Iran: Cultural and Historical Zones

Videos

.jpg)