Turkish Kurdistan

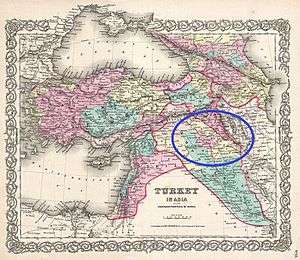

Turkish Kurdistan or Northern Kurdistan (Kurdish: Bakurê Kurdistanê) is the portion of Kurdistan under the jurisdiction of Turkey, located in the Eastern Anatolia and Southeastern Anatolia regions, where Kurds form the predominant ethnic group. The Kurdish Institute of Paris estimates that there are 20 million Kurds living in Turkey, the majority of them in Kurdistan.[1]

.png)

|

|

|

Modern history

|

Kurds generally consider southeastern Turkey (Northern Kurdistan) to be one of the four parts of a Greater Kurdistan, which also includes parts of northern Syria (Western Kurdistan), northern Iraq (Southern Kurdistan), and northwestern Iran (Eastern Kurdistan).[2]

The term Turkish Kurdistan is often associated and used in the context of Kurdish nationalism, which makes it a controversial term among proponents of Turkish nationalism. There is ambiguity about its geographical extent, and the term has different meaning depending on context. Scientific papers and news media frequently use the term.[3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10]

Geography and economy

According to Encyclopædia Britannica 13 of the 81 provinces of Turkey have Kurdish majorities: Iğdır, Tunceli, Bingöl, Muş, Ağrı, Adıyaman, Diyarbakır, Siirt, Bitlis, Van, Şanlıurfa, Mardin and Hakkâri.[11]

In 1987, the Encyclopaedia of Islam described Turkish Kurdistan, historically, as covering at least 17 provinces of Turkey: Adıyaman, Ağrı, Bingöl, Bitlis, Diyarbakır, Elazığ, Erzincan, Erzurum, Hakkâri, Kars, Malatya, Mardin, Muş, Siirt, Şanlıurfa, Tunceli and Van. The Encyclopaedia of Islam stresses at the same time that "the imprecise limits of the frontiers of Kurdistan hardly allow an exact appreciation of the area."[12] Since 1987, four new provinces—Şırnak, Batman, Iğdır and Ardahan—have been created inside the Turkish administrative system out of the territory of some of these provinces.

The region forms the south-eastern edge of Anatolia. It is dominated by high peaks rising to over 3,700 m (12,000 ft) and arid mountain plateaux, forming part of the arc of the Taurus Mountains. It has an extreme continental climate—hot in the summer, bitterly cold in the winter. Despite this, much of the region is fertile and has traditionally exported grain and livestock to the cities in the plains. The local economy is dominated by animal husbandry and small-scale agriculture, with cross-border smuggling (especially of petroleum) providing a major source of income in the border areas. Larger-scale agriculture and industrial activities dominate the economic life of the lower-lying region around Diyarbakır, the largest Kurdish-majority city in the region. Elsewhere, however, decades of conflict and high unemployment has led to extensive migration from the region to other parts of Turkey and abroad.[13]

History

Part of the Fertile Crescent of the Ancient Near East, Northern Kurdistan was quickly affected by the Neolithic Revolution that saw the spread of agriculture. In the Bronze Age, it was ruled by the Arameans, followed by the Neo-Assyrian Empire in the Iron Age. Classical antiquity saw the arrival of first Greater Armenia, then the Roman Empire. The early Muslim conquests swept over the region with the spread of Islam.

During the Middle Ages, the region came under the rule of local chieftains. In the 10th and 11th centuries, it was ruled by the Kurdish Marwanid dynasty. From the 14th century onwards, the region was mostly incorporated into the Ottoman Empire.

Kurdish principalities of the region

A tax register (or defter) dating back to 1527, mentions an area called vilayet-i Kurdistan, which included 7 major and 11 minor emirates (or principalities). The document refers to Kurdish emirates as eyalet(state), an indication of the autonomy enjoyed by these principalities. In a Ferman (imperial decree) issued by Suleiman I, around 1533, he outlines the rules of inheritance and succession among Kurdistan beys i.e. Kurdish nobility. Hereditary succession was granted to Kurdish emirates loyal to the Ottomans, and Kurdish princes were granted autonomy within the Empire. The degree of autonomy of these emirates varied greatly and depended on their geopolitical significance. The weak Kurdish tribes were forced to join stronger ones or become a part of Ottoman sancaks (or sanjak). However, the powerful and less accessible tribes, particularly those close to the Iranian border, enjoyed high degrees of autonomy. According to a kanunname(book of law) mentioned by Evliya Çelebi, there were two administrative units different from regular sanjaks: 1) Kurdish sanjaks (Ekrad Beyliği), characterized by the hereditary rule of the Kurdish nobility and 2) Kurdish governments (hükümet). The Kurdish sanjaks like ordinary sanjaks had some military obligations and had to pay some taxes. On the other hand, the Kurdish hükümet neither pay taxes nor provided troops for the Ottoman Army. The Ottomans preferred not to interfere in their succession and internal affairs. As Evliya Çelebi has reported, by the mid-17th century the autonomy of Kurdish emirates had diminished. At this time, out of 19 sanjaks of Diyarbakir, 12 were regular Ottoman sanjaks, and the remaining were referred to as Kurdish sanjaks. Kurdish sanjaks were reported as Sagman, Kulp, Mihraniye, Tercil, Atak, Pertek, Çapakçur and Çermik. He also reported the Kurdish states or hükümets as Cezire, Egil, Genç, Palu and Hazo. In the late 18th and early 19th century, with the decline of Ottoman Empire, the Kurdish principalities became practically independent.[14]

Modern history

The Ottoman government began to assert its authority in the region in the early 19th century. Concerned with independent-mindedness of Kurdish principalities, Ottomans sought to curb their influence and bring them under the control of the central government in Constantinople. However, removal from power of these hereditary principalities led to more instability in the region from the 1840s onwards. In their place, sufi sheiks and religious orders rose to prominence and spread their influence throughout the region. One of the prominent Sufi leaders was Shaikh Ubaidalla Nahri, who began a revolt in the region between Lakes Van and Urmia. The area under his control covered both Ottoman and Qajar territories. Shaikh Ubaidalla is regarded as one of the earliest leaders who pursued modern nationalist ideas among Kurds. In a letter to a British Vice-Consul, he declared: the Kurdish nation is a people apart. . . we want our affairs to be in our hands'.'[15]

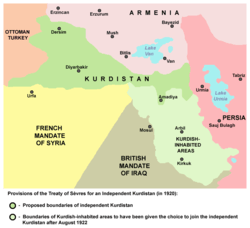

The breakup of the Ottoman Empire after its defeat in the First World War led to its dismemberment and establishment of the present-day political boundaries, dividing the Kurdish-inhabited regions between several newly created states. The establishment and enforcement of the new borders had profound effects for the Kurds, who had to abandon their traditional nomadism for village life and settled farming.[16]

Education

There has been significant conflict in Turkey over the Kurdish populations' linguistic rights. At various points in its history Turkey has enacted laws prohibiting the use of Kurdish in schools.[17]

In 2014, several Kurdish NGOs and two Kurdish political parties supported a boycott of schools in Northern Kurdistan to promote the right to education in the Kurdish language in all subjects. While Kurdish identity has become more acceptable in Turkish society, the Turkish government has only allowed the Kurdish language to be offered as an elective in schools. The government has refused to honor other demands. In several southeastern cities, Kurds have established private schools to teach classes in Kurdish but the police have been closing down these private schools.[18]

Conflict and controversy

| Part of a series on the Kurdish–Turkish conflict | ||||

| Kurdish–Turkish peace process | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

.png) | ||||

|

History

|

||||

|

Primary concerns |

||||

|

International brokers |

||||

|

Proposals |

||||

Kurds generally consider southeastern Turkey to be one of the four parts of a Greater Kurdistan, which also includes parts of northern Syria (Rojava or Western Kurdistan), northern Iraq (Southern Kurdistan), and northwestern Iran (Eastern Kurdistan).[19]

There has been a long-running separatist conflict in Turkey which has cost 30,000 lives, on both sides. The region saw several major Kurdish rebellions during the 1920s and 1930s. These were forcefully put down by the Turkish authorities and the region was declared a closed military area from which foreigners were banned between 1925 and 1965. The use of Kurdish language was outlawed, the words Kurds and Kurdistan were erased from dictionaries and history books, and the Kurds were only referred to as Mountain Turks.[20]

In 1983, a number of provinces were placed under martial law in response to the activities of the militant separatist Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK).[21] A guerrilla war took place through the rest of the 1980s and into the 1990s. By 1993, the total number of security forces involved in the struggle in southeastern Turkey was about 200,000, and the conflict had become the largest counter-insurgency in the Middle East,[22] in which much of the countryside was evacuated, thousands of Kurdish-populated villages were destroyed, and numerous extra judicial summary executions were carried out by both sides.[13] More than 37,000 people were killed in the violence and hundreds of thousands more were forced to leave their homes.[23] The situation in the region has since eased following the capture of the PKK leader Abdullah Öcalan in 1999 and the introduction of a greater degree of official tolerance for Kurdish cultural activities, encouraged by the European Union.[16] However, some political violence is still ongoing and the Turkish–Iraqi border region remains tense.[24]

The 1965 Census: ethnic groups and languages

Turkish Kurdistan is inhabited predominantly by ethnic Kurds, with Turkish, Arab and Assyrian minorities.[25][26]

In the census of 1965, Kurdish-speakers made up the majority in Ağrı, Batman, Muş, Bingöl, Tunceli, Bitlis, Mardin, Şanlıurfa, Hakkâri, Siirt, Şırnak, and Van, and the plurality in Diyarbakır.[25][26]

Since the 1990s, forced immigration from the southeast has brought millions of Kurds to cities like Istanbul, Ankara and Izmir.[18]

| Mother tongue[25] | Populationa | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Kurdish | 1,149,166 | 60.8% |

| Turkish | 535,880 | 28.4% |

| Arabic | 124,586 | 6.6% |

| Zazaki | 60,326 | 3.2% |

| Other | 19,965 | 1.1% |

| Total | 1,889,923 | 100% |

- Notes

^a The source is the Turkish 1965 census. The provinces included are: Ağrı, Bitlis, Diyarbakır, Hakkari, Mardin, Siirt (including Batman and Şırnak) and Van.[25]

See also

References

- The Kurdish Population by the Kurdish Institute of Paris, 2017 estimate. "The territory, which the Kurds call Northern Kurdistan (Bakurê Kurdistanê), has 14.2 million inhabitants in 2016. According to several surveys, 86% of them are Kurds... So in 2016, there are about 12.2 million Kurds still living in Kurdistan in Turkey. We know that there are also strong Kurdish communities in the big Turkish metropolises like Istanbul, Izmir, Ankara, Adana, and Mersin. The numerical importance of this "diaspora" is estimated according to sources at 7 to 10 million... Assuming an average estimate of 8 million Kurds in the Turkish part of Turkey, thus arrives at the figure of 20 million Kurds in Turkey."

- Kurdish Awakening: Nation Building in a Fragmented Homeland, (2014), by Ofra Bengio, University of Texas Press

- de Vos, Hugo; Jongerden, Joost; van Etten, Jacob (2008). "Images of war: Using satellite images for human rights monitoring in Turkish Kurdistan". Disasters. 32 (3): 449–466. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7717.2008.01049.x. PMID 18958914.

- Nevo, E; Beiles, A; Kaplan, D (24 September 1987). "Genetic diversity and environmental associations of wild emmer wheat, in Turkey". Heredity. 61: 31–45. doi:10.1038/hdy.1988.88.

- Van Bruinessen, M (1988). "Between guerrilla war and political murder: The Workers' Party of Kurdistan" (PDF). Middle East Report. 153: 40–50. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- Deborah, Rund; Tirza, Cohen; Dvora, Filon; Carol, Dowling; Tina, Warren; Igal, Barak; Eliezer, Rachmilewitz; Haig, Kazazian; Ariella, Oppenheim (1991). "Evolution of a genetic disease in an ethnic isolate: beta-thalassemia in the Jews of Kurdistan". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 88 (1): 310–314. Bibcode:1991PNAS...88..310R. doi:10.1073/pnas.88.1.310. PMC 50800. PMID 1986379.

- van Bruinessen, Martin (1996). "Kurds, Turks and the Alevi revival in Turkey". Middle East Report. 200 (200): 7–10. doi:10.2307/3013260. JSTOR 3013260.

- E. Fuller, Graham (1993). "The Fate of the Kurds". Foreign Affairs. 72 (2): 108–121. doi:10.2307/20045529. JSTOR 20045529.

- MICHAEL, GUNTER (2004). "The Kurdish Question in Perspective". World Affairs. 166 (4): 197–205. doi:10.3200/WAFS.166.4.197-205. JSTOR 20672696.

- Davis, P.H. (1995). "Lake Van and Turkish Kurdistan: A Botanical Journey". The Geographical Journal. 122 (2): 156–165. doi:10.2307/1790844. JSTOR 1790844.

- "Kurdistan | region, Asia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- Khanam, R. (2005). Encyclopaedic Ethnography of Middle-East and Central Asia. A-I, V. 1. Global Vision Publishing House. p. 470. ISBN 9788182200623.

- van Bruinessen, Martin. "Kurdistan." Oxford Companion to the Politics of the World, 2nd edition. Joel Krieger, ed. Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Ozoglu, Hakan. State-Tribe Relations: Kurdish Tribalism in the 16th- and 17th- Century Ottoman Empire, pp.15,18–22,26, British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, 1996

- Dahlman, Carl. The Political Geography of Kurdistan, Eurasian Geography and Economics, Vol. 43, No. 4, 2002, p.278

- "Kurd," Encyclopædia Britannica. Ultimate Reference Suite. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, 2007.

- Hassanpour, Amir (1996). "The Non-Education of Kurds:A Kurdish Perspective". International Review of Education. 42 (4): 367–379. Bibcode:1996IREdu..42..367H. doi:10.1007/bf00601097.

- "Kurdish identity becomes more acceptable in Turkish society", Al-Monitor, 2014

- Kurdish Awakening: Nation Building in a Fragmented Homeland, (2014), by Ofra Bengio, University of Texas Press

- G. Chaliand, A.R. Ghassemlou, M. Pallis, A People Without A Country, 256 pp., Zed Books, 1992, ISBN 1-85649-194-3, p.58

- "Kurd," Hutchinson Unabridged Encyclopedia including Atlas, 2005.

- "Turkey," Encyclopædia Britannica. Ultimate Reference Suite. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, 2007.

- "Kurdish rebels kill Turkey troops", BBC News, 8 May 2007.

- "Turkish soldiers killed in blast", BBC News, 24 May 2007.

- Heinz Kloss & Grant McConnel, Linguistic composition of the nations of the world, vol,5, Europe and USSR, Québec, Presses de l'Université Laval, 1984, ISBN 2-7637-7044-4

- Ahmet Buran Ph.D., Türkiye'de Diller ve Etnik Gruplar, 2012

External links

- Maps of Kurdish Regions by GlobalSecurity.org

- Map of Kurdish Population Distribution by GlobalSecurity.org

.jpg)