Reconquista (Mexico)

The Reconquista ("reconquest") is a term that is used (not exclusively) to describe the vision by different individuals, groups, and/or nations that the Southwestern United States should be politically or culturally reconquered by Mexico. These opinions are often formed on the basis that those territories had been claimed by Spain for centuries and had been claimed by Mexico from 1821 until being ceded to the United States in the Texas annexation (1845) and the Mexican Cession (1848), as a consequence of the Mexican–American War.[1]

Background

The term Reconquista means "reconquest", and is an analogy to the Christian Reconquista of Moorish Iberia, as the areas of greatest Mexican immigration and cultural diffusion are conterminous with the territories the United States gained from Mexico in the 19th century.[2]

Cultural views

Mexican writers

In a 2001 article on Latin American web portal Terra entitled "Advancement of the Spanish language and Hispanics is like a Reconquista (Reconquest)", Elena Poniatowska said:

A US media outlet recently stated that in some places like Los Angeles, if you didn't speak Spanish, you were "out". It's sort of a reconquista (reconquest) of lost territories that have Spanish names and were once Mexican.

[With a cordial tone, taking pauses, and with a smile on her lips, the Mexican writer commented with satisfaction the change that is happening in the US with regards to the perception of Hispanics and the progress of the Latino community in migratory movements]

The people of the cockroach, of the flea, who come from poverty and misery, are slowly advancing towards the United States and devouring it. I do not know what is to become of all this [in reference to the supposed racism that can ostensibly still be perceived in the US and other countries], but it [racism] seems to be an innate illness in mankind.[3]

In his keynote address at the Second International Congress of the Spanish language held in Valladolid, Spain, in 2003 entitled "Unity and Diversity of Spanish, Language of Encounters", with regards to "reconquista", Carlos Fuentes said:

Well, I've just used an English expression (a reference to having said 'brain trust' in the preceding paragraph) and that brings me back to the American continent, where 400 million men and women, from the Río Bravo to Cape Horn, speak Spanish in what were the domains of the Spanish Crown for 300 years; but in a continent, where, in the north of Mexico, in the United States, another 35 million people also speak Spanish, and not only in the territory that belonged to New Spain first and Mexico until 1848—that southwestern border that extends from Texas to California—but to the north Pacific of Oregon, to the midwest of Chicago and even to the east coast of New York City.

For that reason, one speaks of a reconquista (reconquering) of the old territories of the Spanish Empire in North America. But we must call attention to the fact that we need to go beyond the number of how many people speak Spanish to the question of whether or not Spanish is competitive in the fields of science, philosophy, computer science, and literature in the entire world, an issue brought up recently by Eduardo Subirats.

We can answer in the negative, that no, in the field of science, despite having prominent scientists, we cannot add, so says the great Colombian man of science, Manuel Elkin Patarroyo, we do not have, in Ibero-America, more than 1% of the scientists of the world.[4]

In another part of his discourse, Fuentes briefly returns to his idea of "reconquista":

It is interesting to note the appearance of a new linguistic phenomenon that Doris Sommer of Harvard University, calls with grace and precision, 'the continental mixture,' spanglish or espanglés, since, sometimes, the English expression is used, and, at other times, the Spanish expression, is a fascinating frontier phenomenon, dangerous, at times, always creative, necessary or fatal like the old encounters with Náhuatl (Aztec language), for example, thanks to the Spanish language and some other languages, we can today say chocolate, tomato, avocado, and if one does not say wild turkey (guajolote), one can say turkey (pavo), that is why the French converted our word of American turkey (guajolote) into fowl of the Indies, oiseaux des Indes o dindon, while the English people, completely disoriented with regards to geography, give it the strange name of Turkey (name of the country), turkey (bird), but, perhaps due to some ambitions that are not confessable in the Mediterranean, and from Gibraltar to the Bosforus strait.

In summary, reconquista today, but, pre-factum, re-conquest - will take us to factum. The Conquest and Colonization of the Americas by way of Spain's military and its humanities was a multiple paradox. It was a catastrophe for the indigenous communities, notable for the great Indian civilizations of Mexico and Peru.

But a catastrophe, cautions María Zambrano, is only catastrophic if nothing redeeming comes of it.

From the catastrophe of the Conquest, all of us were born, the indigenous-iberian-americans. Immediately, we were mestizos, women and men of Indian blood, Spanish, and, later, African. We were Catholics, but our Christianity was in the syncretic refuge of the indigenous and African cultures. And we speak Spanish, but we gave it an American, Peruvian, Mexican inflection to the language ... the Spanish language stopped being the language of Empire, and it turned into something much more ... [it became] the universal language of recognition between the European and indigenous cultures ...[4]

Thus, Poniatowska and Fuentes' concept of reconquista can be viewed as a metaphor for the linguistic tendencies by a diverse group of peoples who share a common and historical connection to the Spanish language within the Americas over the course of 500 years, which, incidentally, includes the border region of the Southwest United States.

Nationalist Front of Mexico

The fringe group Nationalist Front of Mexico opposes what it sees as Anglo-American cultural influences[5] and rejects the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, as well as what its members consider the "American occupation" of territory formerly belonging to Mexico and now form the southwestern United States.

On its website, the front states:

We reject the occupation of our nation in its northern territories, an important cause of poverty and emigration. We demand that our claim to all the territories occupied by force by the United States be recognized in our Constitution, and we will bravely defend, according to the principle of self-determination to all peoples, the right of the Mexican people to live in the whole of our territory within its historical borders, as they existed and were recognized at the moment of our independence.[6]

Charles Truxillo

A prominent advocate of Reconquista was Chicano activist and adjunct professor Charles Truxillo (1953–2015)[7] of the University of New Mexico (UNM), who envisioned a sovereign Hispanic nation called the República del Norte (Republic of the North) that would encompass Northern Mexico, Baja California, California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas.[8] He supported the secession of US Southwestern states to form an independent Chicano nation, arguing that the Articles of Confederation gave individual states full sovereignty and thus the legal right to secede.[7][9]

Truxillo, who taught at UNM's Chicano Studies Program on a yearly contract, suggested in an interview that "Native-born American Hispanics feel like strangers in their own land."[9] He said, "We remain subordinated. We have a negative image of our own culture, created by the media. Self-loathing is a terrible form of oppression. The long history of oppression and subordination has to end" and that on both sides of the US–Mexico border "there is a growing fusion, a reviving of connections ... Southwest Chicanos and Norteno Mexicanos are becoming one people again."[9] Truxillo stated that Hispanics who have achieved positions of power or otherwise are "enjoying the benefits of assimilation" are most likely to oppose a new nation, explaining that

There will be the negative reaction, the tortured response of someone who thinks, "Give me a break. I just want to go to Wal-Mart." But the idea will seep into their consciousness, and cause an internal crisis, a pain of conscience, an internal dialogue as they ask themselves: "Who am I in this system?"[9]

Truxillo believed that the República del Norte would be brought into existence by "any means necessary" but that it was unlikely to be formed by civil war but rather by the electoral pressure of the future majority Hispanic population in the region.[9][10] Truxillo added that he believed it's his job to help develop a "cadre of intellectuals" to think about how this new state can become a reality.[9]

In 2007, the UNM reportedly decided to stop renewing Truxillo's yearly contract. Truxillo claimed that his "firing" was due to his radical beliefs, arguing that "Tenure is based on a vote from my colleagues. Few are in favor of a Chicano professor advocating a Chicano nation state."[11]

José Ángel Gutiérrez

In an interview with In Search of Aztlán on 8 August 1999, José Ángel Gutiérrez, a political science professor at the University of Texas at Arlington, stated that:

We're the only ethnic group in America that has been dismembered. We didn't migrate here or immigrate here voluntarily. The United States came to us in succeeding waves of invasions. We are a captive people, in a sense, a hostage people. It is our political destiny and our right to self-determination to want to have our homeland [back]. Whether they like it or not is immaterial. If they call us radicals or subversives or separatists, that's their problem. This is our home, and this is our homeland, and we are entitled to it. We are the host. Everyone else is a guest. ... It is not our fault that whites don't make babies, and blacks are not growing in sufficient numbers, and there's no other groups with such a goal to put their homeland back together again. We do. Those numbers will make it possible. I believe that in the next few years, we will see an irredentists movement, beyond assimilation, beyond integration, beyond separatism, to putting Mexico back together as one. That's irridentism [sic]. One Mexico, one nation.[12]

In an interview with the Star-Telegram in October 2000, Gutiérrez stated that many recent Mexican immigrants "want to recreate all of Mexico and join all of Mexico into one. And they are going to do that, even if it's just demographically ... They are going to have political sovereignty over the Southwest and many parts of the Midwest."[13] In a videotape made by the Immigration Watchdog website (as cited in The Washington Times), Gutiérrez is quoted as saying, "We are millions. We just have to survive. We have an aging white America. They are not making babies. They are dying. It's a matter of time. The explosion is in our population."[8] In a subsequent interview with The Washington Times in 2006, Gutiérrez backtracked and said there was "no viable" Reconquista movement, and blamed interest in the issue on closed-border groups and "right-wing blogs".[8]

Other views

Felipe Gonzáles, a professor at the University of New Mexico (UNM), who is director of UNM's Southwest Hispanic Research Institute, has stated that while there is a "certain homeland undercurrent" among New Mexico Hispanics, the "educated elites are going to have to pick up on this idea [of a new nation] and run with it and use it as a point of confrontation if it is to succeed." Juan José Peña of the Hispano Round Table of New Mexico believes that Mexicans and Mexican Americans currently lack the political consciousness to form a separate nation, stating that "Right now, there's no movement capable of undertaking it."[9][14]

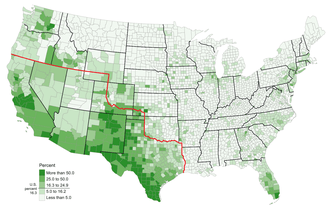

Illegal immigration into the southwest states is sometimes viewed as a form of reconquista, in light of the fact that Texas statehood was preceded by an influx of US settlers into that Mexican province until United States citizens outnumbered Mexicans 10–1 and were able to take over governance of the area. The theory is that the reverse will happen as Mexicans eventually become so numerous in that region that they can wield substantial influence, including political power.[15] Even if not intended, some analysts say the significant demographic shift in the American Southwest may result in "a de facto reconquista."[8]

A May 2006 Zogby poll reported that 58 percent of Mexicans believe that the southwestern US belongs to Mexico.[16]

The American political scientist Samuel P. Huntington, a proponent of the widespread popularity of Reconquista, stated in 2004 that:

Demographically, socially and culturally, the reconquista (re-conquest) of the Southwest United States by Mexican immigrants is well under way. [However, a] meaningful move to reunite these territories with Mexico seems unlikely ... No other immigrant group in U.S. history has asserted or could assert a historical claim to U.S. territory. Mexicans and Mexican-Americans can and do make that claim.[17]

The neoliberal political writer Mickey Kaus has remarked,

Reconquista is a little—a little extreme. If you talk to people in Mexico, I'm told, if you get them drunk in a bar, they'll say we're taking it back, sorry. That's not an uncommon sentiment in Mexico, so why can't we take it seriously here? ... This is like a Quebec problem if France was next door to Canada.[18]

Other Hispanic rights leaders say that Reconquista is nothing more than a fringe movement. Nativo Lopez, president of the Mexican American Political Association in Los Angeles, when asked about the concept of Reconquista by a reporter, responded "I can't believe you're bothering me with questions about this. You're not serious. I can't believe you're bothering with such a minuscule, fringe element that has no resonance with this populace."[8]

Reconquista sentiments are often jocularly referred to by media targeted to Mexicans, including a recent Absolut Vodka ad that generated significant controversy in the United States for its printing of a map of pre–Mexican–American war Mexico.[19] Reconquista is a recurring theme in contemporary fiction and non-fiction,[20] particularly among far-right authors.[21]

The National Council of La Raza, the largest national Hispanic civil rights and advocacy organization in the United States, has stated on its website that it "has never supported and does not endorse the notion of a Reconquista (the right of Mexico to reclaim land in the southwestern United States) or Aztlán."[22]

In an editorial written in Investor's Business Daily, it said efforts by past Mexican government officials to influence the 2016 election was a form of "reconquista".[23] This view was not shared in an editorial in the American Thinker, which pointed towards Californio independence from Mexico in the mid-19th century.[24]

Real approaches

Historical

In 1915, the capture of Basilio Ramos (an alleged supporter of the Mexican dictator Victoriano Huerta) in Brownsville, Texas, revealed the existence of the Plan of San Diego, which stated goal was to reconquer the southwestern United States in order to gain domestic support in Mexico for Huerta. However, other theories point that "the plan" was created to push the US into supporting Venustiano Carranza, a major leader of the Mexican revolution (which ultimately occurred).

In 1917, according to the intercepted Zimmermann Telegram, in exchange for joining Germany as an ally against the United States during World War I, Germany was ready to assist Mexico to "reconquer" its lost territories of Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona.

Modern

For Chicanos in the 1960s, the term, although not invoked, was understood as taking back "Aztlán", by spray painting as many Mexican images as they could on any wall or sign they could find.

In the late 1990s to early 2000s, as US census data showed that the population of Mexican Americans in the Southwestern United States had increased, the term was popularized by contemporary Mexican intellectuals, such as Carlos Fuentes, Elena Poniatowska, and President Vicente Fox,[8][17][25] who spoke of Mexican immigrants maintaining their culture and Spanish language in the United States as they migrated in greater numbers to this area.

In March 2015, at the midst of the War in Ukraine, when the US was planning on supporting Ukraine to fight against Russia, Dukuvakha Abdurakhmanov, the speaker of the Chechen parliament, threatened to arm Mexico against the United States and questioned the legal status of the territories of California, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, Utah, Colorado and Wyoming.[26]

See also

References

- Grillo, Ioan (2011). El Narco: Inside Mexico's Criminal Insurgency. New York: Bloomsbury Press (published 2012). pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-1-60819-504-6.

- Bailey, Richard W. (2012). Speaking American: A History of English in the United States. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 182. ISBN 978-0-19-517934-7.

- "Poniatowska: 'Avance de español e hispanos es como una reconquista'" [Advancement of Spanish Language and of Hispanics is Like a Reconquista] (in Spanish). Terra. 2001. Archived from the original on 29 December 1996. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- Fuentes, Carlos (2003). "Unidad y diversidad del español, lengua de encuentros" [Unity and Diversity of the Spanish Lanuguage, Language of Encounters]. Congresos de la Lengua (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 22 April 2008. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- "Neonazismo a la Mexicana" [Neonazism, Mexican Style]. Revista Proceso (in Spanish). 22 September 2008. Archived from the original on 5 April 2012. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- "Norma programática" (in Spanish). Vanduardia Nacional Mexicanista. 2011. Archived from the original on 13 February 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- "Remembering Dr. Charles Truxillo". UNM Continuing Education Blog. Albuquerque, New Mexico: University of New Mexico. 9 February 2015. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- "Mexican Aliens Seek to Retake 'Stolen' Land". The Washington Times. 16 April 2006. Archived from the original on 14 October 2008. Retrieved 14 February 2013.

- "Professor Predicts 'Hispanic Homeland'". Kingman Daily Miner. 120 (74). Kingman, Arizona. Associated Press. 2 February 2000. p. 11. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- Tancredo Praises Cuesta's Book Exposing Hispanic Autonomy Arising From Immigration, Prleap.com (reprinted on Wexico.com), 30 April 2007.

- Nealy, Michelle J. (20 November 2007). "Chicano Nationalist Professor Fired Despite Student Protests of Censorship". DiverseEducation.com. Retrieved 6 December 2010.

- "In Search of Aztlán: José Angel Gutiérrez Interview". In Search of Aztlán. 8 August 1999. Archived from the original on 7 August 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- Melendez, Michelle (18 October 2000). "Interview of La Raza Unida Party Founder Jose Angel Gutierrez". Star-Telegram. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 25 July 2018 – via www.aztlan.net.

- "Hispano Round Table de Nuevo México". www.nmhrt.org.

- The Bulletin - Philadelphia's Family Newspaper - 'Absolut' Arrogance Archived 16 April 2000 at the Wayback Machine

- "American Views of Mexico and Mexican Views of the U.S." NumbersUSA. Zogby. 25 May 2006. Archived from the original on 16 April 2000. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- Huntington, Samuel P. (2004). "The Hispanic Challenge". Foreign Policy. No. 141. p. 42. doi:10.2307/4147547. ISSN 0015-7228. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- Gillespie, Nick (2010). "Unions 'Own the Democratic Party'". Reason. Vol. 42 no. 4. Escondido, California. ISSN 0048-6906. Archived from the original on 16 April 2000. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- "U.S. Vodka-Maker Teases Absolut over Mexico Ad". Albuquerque Journal. Albuquerque, New Mexico. Archived from the original on 16 April 2000. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- The Second Mexican-American War (The Guns, Ammo and Alcohol Trilogy Book 1). – 21 September 2012 by Les Harris (Author).

The Aztlan Protocol: Return of an Old World Order. – 26 October 2014 by Aldéric Au (Author). - Buchanan, Patrick J. (2006). State of Emergency: The Third World Invasion and Conquest of America.

- "Reconquista and Segregation". National Council of La Raza. Archived from the original on 16 July 2010. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- "Mexico's Ballot-Box Reconquista". Investor's Business Daily. 21 March 2016. Archived from the original on 16 April 2000. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- Windchy, Eugene G. (16 June 2016). "'Reconquista' Is the Wrong Term". American Thinker. El Cerrito, California. Archived from the original on 16 April 2000. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- Monjas, Javier (18 April 2006). "La otra 'Reconquista': Las protestas migratorias en Estados Unidos potencian a movimientos de recuperación de la tierra 'robada' a México en medio de las apocalípticas advertencias de Samuel Huntington sobre el fin del 'sueño americano'" (in Spanish). Nuevo Digital Internacional. Archived from the original on 16 April 2000. Retrieved 14 February 2013.

- Clinch, Matt (27 March 2015). "Chechnya Threatens to Arm Mexico against US". CNBC. Archived from the original on 16 April 2000. Retrieved 26 July 2018.