Status of the Irish language

The official status of the Irish language remains high in the Republic of Ireland, and the total number of people who answered 'yes' to being able to speak Irish in April 2016 was 1,761,420, which represents 39.8 per cent of respondents out of a population of 4,921,500 (2019 estimate) in the Republic of Ireland. In Northern Ireland 104,943 identify as being able to speak Irish out of a population of 1,882,000 (2018 estimate). The official status reflects the dominance of the language in Irish cultural and social history until the nineteenth century and its role in Irish cultural identity, even though the daily use of Irish today is limited.

It has been argued that studies have consistently shown Irish to be an important part of Irish identity. It has been found, however, that while ideological support for Irish is high, actual routine use is very low, and that there is no correlation between actual personal ability with the language and its perceived value as an identity-marker.[1] Nevertheless, the language benefits from the support of activists who continue to use it as a social and cultural medium.

On 13 June 2005, Irish was made an official language of the European Union, the new arrangements coming into effect on 1 January 2007. It is, however, the least widely routinely spoken of all 24 official languages of the European Union.

Traditional Irish speakers in the areas known as the Gaeltacht have usually been considered as the core speakers of the language. Their number, however, is diminishing, and it is argued that they are being replaced in importance by fluent speakers outside the Gaeltacht. These include both second-language speakers and a small minority who were raised and educated through Irish. Such speakers are predominantly urban dwellers.

Claimed number of Irish speakers

In Ireland

In the Irish census of 2016, 1,761,420 people claimed to be able to speak the Irish language (the basic census question does not specify extent of usage, or ability level), with more females than males so identifying (968,777 female speakers (55%) compared with 792,643 males (45%)). Further to these numbers, 23.8% indicated that they never spoke the language, while a further 31.7% indicated that they only spoke it within the education system. 6.3% (111,473 people) claimed to speak it weekly, and daily speakers outside the education system numbered only 73,803, that is 1.7% of the population. Of the daily speakers, a substantial majority (53,217) lived outside the Gaeltacht.[2][3]

Some 4,130 people (0.2%) in Northern Ireland use Irish as their main home language,[4] with (according to the 2011 UK Census) 184,898 having a little knowledge of the language.

Estimates of fully native Irish language speakers in Ireland range from 40,000 to 80,000.[5][6][7]

Only 8,068 of the 2016 census forms were completed in Irish.[8] In anecdotal input, Bank of Ireland has noted that fewer than 1% of their customers use the Irish language option on their banking machines.[9]

Outside Ireland

The number of Irish speakers outside Ireland cannot be readily verified. In 2015 the United States Census Bureau released the 2009-2013 American Community Survey, providing information on "languages spoken at home." The number of Irish speakers in 2010 was given as 20,590 (with a margin of error of 1,291), the states with the largest numbers being New York (3,005), California (2,575), Massachusetts (2,445), Illinois (1,560), New Jersey (1,085) and Florida (1,015). These figures give no evidence of proficiency.[10] There is no information readily available as to the number of Irish speakers in Australia.[11] The same is true of England and Wales.[12] Statistics on languages spoken at home (as gathered in the United States and Australia) give no indication of the number of speakers who use those languages in other contexts.

Trends in usage

It has been argued that Gaeilgeoirí tend to be more highly educated than monolingual English speakers, and enjoy the benefits of language-based networking, leading to better employment and higher social status.[13] Though this initial study has been criticised for making certain assumptions,[14] the statistical evidence supports the view that such bilinguals enjoy certain educational advantages; and the 2016 Republic of Ireland census noted that daily Irish language speakers were more highly educated than the population generally in Ireland. Of those daily Irish speakers who had completed their education, 49 per cent had a third level degree or higher at university or college level. This compared to a rate of 28 per cent for the state overall.[15]

Recent research suggests that urban Irish is developing in a direction of its own and that Irish speakers from urban areas can find it difficult to understand Irish speakers from the Gaeltacht.[16] This is related to an urban tendency to simplify the phonetic and grammatical structure of the language.[16] It has been pointed out, however, that Irish speakers outside the Gaeltacht constitute a broad spectrum, with some speaking an Irish which is closely modelled on traditional versions of the language and others speaking an Irish which is emphatically non-traditional.[17]

The written standard remains the same for all Irish speakers, and urban Irish speakers have made notable contributions to an extensive modern literature.[18]

While the number of fluent urban speakers is rising (largely because of the growth of urban Irish-medium education), Irish in the Gaeltacht grows steadily weaker. The 2016 census showed that inhabitants of the officially designated Gaeltacht regions of Ireland numbered 96,090 people: down from 96,628 in the 2011 census. Of these, 66.3% claimed to speak Irish, down from 68.5% in 2011; and only 21.4% or 20,586 people said they spoke Irish daily outside the education system.[19] It was estimated in 2007 that, outside the cities, about 17,000 people lived in strongly Irish-speaking communities, about 10,000 people lived in areas where there was substantial use of the language, and 17,000 people lived in "weak" Gaeltacht communities. In no part of the Gaeltacht was Irish the only language.[20] Complete or functional monolingualism in Irish is now restricted to a relatively small number of children under school age.

A comprehensive study published in 2007 on behalf of Údarás na Gaeltachta found that young people in the Gaeltacht, despite their largely favourable view of Irish, use the language less than their elders. Even in areas where the language is strongest, only 60% of young people use Irish as the main language of communication with family and neighbours. Among themselves they prefer to use English.[21] The study concluded that, on current trends, the survival of Irish as a community language in Gaeltacht areas is unlikely. A follow-up report by the same author published in 2015 concluded that Irish would die as a community language in the Gaeltacht within a decade.[22]

In 2010 the Irish government launched the 20-Year Strategy for the Irish Language 2010-2030 which is designed to strengthen the language in all areas and greatly increase the number of habitual speakers. This includes the encouragement of Irish-speaking districts in areas where Irish has been replaced by English.[23] The 2015 independent report on the Gaeltacht commissioned by Údarás na Gaeltachta, however, does not regard this strategy as likely to be successful without a radical change in policy at national level.

Usefulness of Irish

It has been said that, although many Irish people see the Irish language as standing for national identity and a collective pride, this is by no means true of all, and that Irish has little utility compared to English.[24] It has been claimed, however, that one of the chief benefits of studying Irish is that it enables the student to see from disparate linguistic standpoints: "The practice of weighing up arguments, forming opinions and expressing challenging concepts in another language teaches students to think outside the monolingual box".[25] It has also been claimed that since the primary language of communication is English and that under normal circumstances there is no need to speak Irish, people use Irish in order to make a cultural statement.[1]

The lack of utility has been disputed. It has been pointed out that barristers with Irish make up a large proportion of the Bar Council, and that there are at least 194 translators who work through Irish and are licensed by Foras na Gaeilge. The European Union regularly advertises competitions for positions, including those for lawyer-linguists. There is also a demand for teachers, given that there are over 370 primary and secondary Irish-medium and Gaeltacht schools. There is increasing demand for Irish-language teachers abroad, with scholarships available for travel to America and Canada. In the area of broadcast media there are many job opportunities for bilingual researchers, producers, journalists, IT and other technical specialists. Opportunities also exist for Irish-speaking actors and writers, especially in television. Many Irish speakers are employed by public relations firms because of a need for clients to be represented in the Irish media and to comply with the requirements of the Official Languages Act.[26]

Republic of Ireland

The vast majority of Irish in the Republic are, in practice, monolingual English speakers. Habitual users of Irish fall generally into two categories: traditional speakers in rural areas (a group in decline) and urban Irish speakers (a group in expansion).

The number of native Irish-speakers in Gaeltacht areas of the Republic of Ireland today is far lower than it was at independence. Many Irish-speaking families encouraged their children to speak English as it was the language of education and employment; by the nineteenth century the Irish-speaking areas were relatively poor and remote, though this very remoteness helped the language survive as a vernacular. There was also continuous outward migration of Irish speakers from the Gaeltacht (see related issues at Irish diaspora).

A more recent contributor to the decline of Irish in the Gaeltacht has been the immigration of English speakers and the return of native Irish speakers with English-speaking partners. The Planning and Development Act (2000) attempted to address the latter issue, with varied levels of success. It has been argued that government grants and infrastructure projects have encouraged the use of English:[27] "only about half Gaeltacht children learn Irish in the home... this is related to the high level of in-migration and return migration which has accompanied the economic restructuring of the Gaeltacht in recent decades".[27][28]

In an effort to stop the erosion of Irish in Connemara, the Galway County Council introduced a development plan whereby new housing in Gaeltacht areas must be allocated to English-speakers and Irish-speakers in the same ratio as the existing population of the area. Developers had to enter a legal agreement to that effect.[29]

Law and public policy

On 14 July 2003, An tUachtarán (President) signed the Official Languages Act 2003 into law. This was the first time the provision of state services through Irish had the support of law. The Office of An Coimisinéir Teanga (The Language Commissioner) was established under the Official Languages Act as an independent statutory office operating as an ombudsman's service and as a compliance agency.

In 2006 the government announced a 20-year strategy to help Ireland become a more bilingual country which was launched on 20 December 2010. This involves a 13-point plan and encouraging the use of language in all aspects of life. It aims to strengthen the language in both the Gaeltacht and the Galltacht (see 20-Year Strategy for the Irish Language 2010-2030).[30][31]

Constitution

Article 8 of the Constitution states the following:

- The Irish language as the national language is the first official language.

- The English language is recognised as a second official language.

- Provision may, however, be made by law for the exclusive use of either of the said languages for any one or more official purposes, either throughout the State or in any part thereof.

The interpretation of 8.3 has been problematical and various judgments have cast more light on this matter.

In 1983 Justice Ó hAnnluain noted that Irish is referred to in the present Constitution as 'the first official language' and that the Oireachtas itself can give priority to one language over the other. Until that time it should be assumed that Irish is the first official language, and that the citizen is entitled to require that it be used in administration.[32] In 1988 Justice Ó hAnnluain said it was fair to provide official forms in both Irish and English.[33]

In 2001 Justice Hardiman said that "the individual who seeks basic legal materials in Irish will more than likely be conscious of causing embarrassment to the officials from whom he seeks them and will certainly become conscious that his business will be much more rapidly and efficaciously dealt with if he resorts to English. I can only say that this situation is an offence to the letter and spirit of the Constitution". [34] In the same judgement he stated his opinion that it was improper to treat Irish less favourably than English in the transaction of official business.[34]

In 2009, however, Justice Charleton said that the State has the right to use documents in either language and that there is no risk of an unfair trial if an applicant understands whichever language is used.[35]

In 2010 Justice Macken said that there was a constitutional obligation to provide to a respondent all Rules of Court in an Irish language version as soon as practicable after they were published in English.[36]

The Irish text of the Constitution takes precedence over the English text (Articles 25.4.6° and 63). However, the second amendment included changes to the Irish text to align it more closely with the English text, rather than vice versa. The Constitution provides for a number of Irish language terms that are to be used even in English.

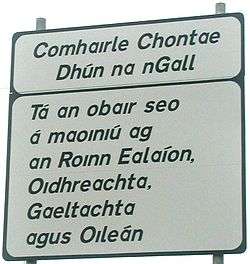

Place names

The Placenames Order/An tOrdú Logainmneacha (Ceantair Ghaeltachta) 2004 requires the original Irish placenames to be used in the Gaeltacht on all official documents, maps and roadsigns. This has removed the legal status of those placenames in the Gaeltacht in English. Opposition to these measures comes from several quarters, including some people in popular tourist destinations located within the Gaeltacht (namely in Dingle) who claim that tourists may not recognise the Irish forms of the placenames.

Following a campaign in the 1960s and early 1970s, most road-signs in Gaeltacht regions have been in Irish only. Most maps and government documents did not change, though Ordnance Survey (government) maps showed placenames bilingually in the Gaeltacht (and generally in English only elsewhere). Most commercial map companies retained the English placenames, leading to some confusion. The Act therefore updates government documents and maps in line with what has been reality in the Gaeltacht for the past 30 years. Private map companies are expected to follow suit.

Cost of Irish

In a 2011 comment on Irish education, Professor Ed Walsh deplored the fact that the State spends about €1,000,000,000 p.a. on teaching Irish, although he did not say how he had arrived at this figure. He called for a

…phased reallocation of part of the €1 billion committed each year to teaching Irish is a good place to start. All students should be introduced to the Irish language at primary level, but after that resources should be directed only to those who have shown interest and commitment. The old policies of compulsion that have so inhibited the restoration of the language should be abandoned.[37]

Professor Walsh's remarks provoked further comment for and against his suggestion.[38][39]

Much of the discussion of the cost of Irish has arisen from its official use in the European Union, particularly with regard to the translation of documents. It has been pointed out that, though the European Parliament does not supply a breakdown of costs by language, on the figures available Irish is not the most expensive to translate of the 24 languages used.[40] The total amount spent on translation of languages per year has been established at €1.1 billion, described as amounting to €2.20 per EU citizen per year. It has been argued that any extra expense incurred in translating into Irish is due to a lack of translators.[41] Such translators in many cases need specialist knowledge, especially of law. The Irish Department of Education provides courses accordingly, run by University College Cork, University College, Galway, and Kings Inns. By 2015 243 translators had been trained at a cost of €11m, and the logging of Irish terms into an international language database had cost €1.85M.[42]

Companies using Irish

People corresponding with state bodies can generally send and receive correspondence in Irish or English. The ESB, Irish Rail/Iarnród Éireann and Irish Water/Uisce Éireann have Irish-speaking customer support representatives and offer both Irish and English language options on their phone lines, along with written communication in both languages. These services are being phased in to all State organisations. The Emergency response number 112 or 999 also have agents who deal with emergency calls in both languages. All state companies are obliged to have bilingual signage and stationery and have Irish language options on their websites with the Official Languages Act 2003. InterCity (Iarnród Éireann) and Commuter (Iarnród Éireann) trains, Luas trams and Bus Éireann and Dublin Bus buses display the names of their destinations bilingually and their internal signage and automated oral announcements on their vehicles are bilingual. Tickets can be ordered from Luas ticket machines in Irish along with in some other languages. Most public bodies have Irish language or bilingual names.

Most private companies in Ireland have no formal provision for the use of Irish, but it is not uncommon for garages, cafes and other commercial establishments to display some signage in Irish.[43][44]

Daily life

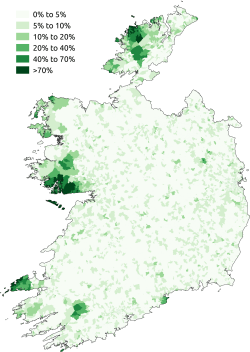

%2C_April_2006.jpg)

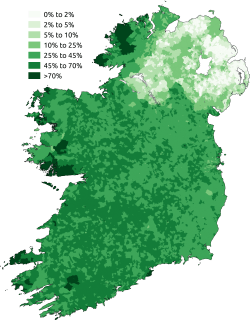

.jpg)

The population of the Republic of Ireland was shown as 4.83 million in the 2018 census. Irish is a main domestic, work or community language for approximately 2% of the population of Ireland.[45] Hiberno-English has been heavily influenced by the Irish language, and words derived from Irish, including whole phrases, continue to be a feature of English as spoken in Ireland: Slán ("goodbye"), Slán abhaile ("get home safely"), Sláinte ("good health"; used when drinking like "bottoms up" or "cheers"). The term craic has been popularised in a Gaelicised spelling: "How's the craic?" or "What's the craic?" ("how's the fun?"/"how is it going?").

Many of the main social media forum websites have Irish language options. These include Facebook, Google, Twitter, Gmail and Wordpress. Several computer software products also have an Irish language option. Prominent examples include Microsoft Office,[46] KDE,[47] Mozilla Firefox,[48] Mozilla Thunderbird,[48] OpenOffice.org,[49] and Microsoft Windows operating systems (since Windows XP SP2).[46]

An Taibhdhearc, based in Galway and founded in 1928, is the national Irish language theatre. There is also a theatre called Amharclann Ghaoth Dobhair, based in the Donegal Gaeltacht. Plays in Irish may sometimes be seen elsewhere.

In 2016 it was announced that Galway City, Dingle and Letterkenny would be the first recognised Bailte Seirbhísí Gaeltachta (Gaeltacht Service Towns) under the Gaeltacht Act 2012 subject to them adopting and implementing approved language plans.[50][51] It is expected that more areas will be designated as formal Bailte Seirbhísí Gaeltachta in the future.

In 2018 it was announced that five areas outside the Gaeltacht on the island of Ireland would be formally recognised as the first Líonraí Gaeilge (Irish Language Networks) under the Gaeltacht Act 2012. The areas in question are Belfast, Loughrea, Carn Tóchair, Ennis and Clondalkin.[52] [53][54] Foras na Gaeilge said it hoped to award the status of Líonraí Gaeilge to other areas in the future.

Partly due to work by Gael-Taca and Gaillimh le Gaeilge, there are residential areas with names in Irish in most counties in Ireland.[55] [56] Over 500 new residential areas were named in Irish during the late 1990s to late 2000s property boom in Ireland.[57][58]

Media

Radio

Irish has a significant presence in radio. RTÉ Raidió na Gaeltachta (Gaeltacht radio) has gone beyond its original brief, covering not only the Gaeltacht but also national and international news and issues. It broadcasts across the island of Ireland on FM, although the station and all of its studios are based in the Republic of Ireland. There are also two Irish language-medium community radio stations: Raidió na Life in Dublin and Raidió Fáilte in Belfast, the former being older and more recognised as an important training station for those wishing to work in radio professionally. There is also a station for young people called Raidió Rí-Rá which is available in some areas on DAB. Other community radio stations usually have at least one Irish-language programme per week, depending on the speakers available. Near FM, the community radio station covering north-east Dublin City, broadcasts "Ar Mhuin na Muice" five days a week.[59]

All stations in the Republic are obliged by the Broadcasting Act 2009 to have Irish language programming. Most commercial radio stations in the Republic have a weekly Irish language programme. RTÉ radio stations have daily Irish language programmes or news reports.

BBC Northern Ireland broadcasts an Irish-language service called Blas.[60]

Television

The Irish-language television station TG4 offers a wide variety of programming, including dramas, rock and pop shows, a technology show, travel shows, documentaries and an award-winning soap opera called Ros na Rún, with around 160,000 viewers per week.[61] In 2015 TG4 reported that overall it has an average share of 2% (650,000 daily viewers) of the national television market in the Republic of Ireland.[62] This market share is up from about 1.5% in the late 1990s. The Ofcom 2014 annual report for Northern Ireland said that TG4 had an average share of 3% of the market in Northern Ireland.[63] TG4 delivers 16 hours a day of television from an annual budget of €34.5 million.

Cúla 4 is a children's television service broadcast in the mornings and afternoons on TG4. There is also a stand-alone children's digital television channel available with the same name with the majority of programmes in Irish and with a range of home-produced and foreign dubbed programmes.

RTÉ News Now is a 24-hour digital television news service available featuring national and international news. It broadcasts mostly English language news and current affairs and also broadcasts Nuacht RTÉ the daily RTÉ 1 Irish language news television programme.

Print

Literature

Though Irish is the language of a small minority, it has a distinguished modern literature. The foremost prose writer is considered to be Máirtín Ó Cadhain (1906–1970), whose dense and complex work has been compared to that of James Joyce. Two major poets are Seán Ó Ríordáin (1907–1977) and the lyricist and scholar Máire Mhac an tSaoi (b. 1922). There are many less notable figures who have produced interesting work.

In the first half of the 20th century the best writers were from the Gaeltacht or closely associated with it. Remarkable autobiographies from this source include An tOileánach ("The Islandman") by Tomás Ó Criomhthain (1856–1937) and Fiche Bliain ag Fás ("Twenty Years A'Growing") by Muiris Ó Súilleabháin (1904–1950). Following demographic trends, the bulk of contemporary writing now comes from writers of urban background.

Irish has also proved to be an excellent vehicle for scholarly work, though chiefly in such areas as Irish-language media commentary and analysis, literary criticism and historical studies.

There are several publishing houses, among them Coiscéim and Cló Iar-Chonnacht, which specialise in Irish-language material and which together produce scores of titles every year.

Religious texts

The Bible has been available in Irish since the 17th century through the Church of Ireland. In 1964 the first Roman Catholic version was produced at Maynooth under the supervision of Professor Pádraig Ó Fiannachta and was finally published in 1981.[64] The Church of Ireland Book of Common Prayer of 2004 is available in an Irish-language version.

Periodicals

Irish has an online newspaper called Tuairisc.ie which is funded by Foras na Gaeilge and advertisers.[65] This replaces previous Foras na Gaeilge-funded newspapers which were available both in print and online. The newspapers Foinse (1996-2013) and Gaelscéal (2010-2013) ceased publication in 2013.[66] Between 1984 and 2003 there was a Belfast-based Irish language weekly newspaper Lá which relaunched as Lá Nua and ran as a daily national newspaper between 2003 and 2008 and had a readership of several thousand. The board of Foras na Gaeilge announced they were ending funding to the newspaper in late 2008 and the newspaper folded soon after.[67]

The Irish News has two pages in Irish every day. The Irish Times publishes the Irish-language page "Bileog" on Mondays and other articles in Irish in the section Treibh. The Irish Independent publishes an Irish language supplement called "Seachtain" on Wednesdays and the Irish Daily Star publish an article in Irish on Saturdays. The immigrants' newspaper Metro Éireann also has an article in Irish every issue, as do many local papers throughout the country.

Several magazines are published in the language. These include the "flagship" monthly review Comhar,[68] devoted to new literature and current affairs, the literary magazine Feasta, which is a publication of the Gaelic League (Conradh na Gaeilge), and An tUltach, a magazine of the Ulster branch of Conradh na Gaeilge. A quarterly magazine An Gael,[69] similar to Comhar, is published in North America. The only culture and lifestyle magazine in Irish directed chiefly to a younger readership is Nós.[70]

Contemporary music and comedy

The revival of Irish traditional folk music in the sixties may initially have hindered the creation of contemporary folk and pop music in Irish. Traditional music, though still popular, now shares the stage with modern Irish-language compositions, a change due partly to the influence of Seachtain na Gaeilge. Yearly albums of contemporary song in Irish now appear, though most are translations from the English. The artists have included Mundy, The Frames, The Coronas, The Corrs, The Walls, Paddy Casey, Kíla, Luan Parle, Gemma Hayes, Bell X1 and comedian/rapper Des Bishop. The Irish-language summer college Coláiste Lurgan has made popular video versions in Irish of English-language pop songs.[71]

There are two Irish-language radio programmes series specialising in popular music that are broadcast on many of the generally English medium commercial radio stations in Ireland, both created by Digital Audio Productions: Top 40 Oifigiúil na hÉireann and Giotaí. Top 40 Oifigiúil na hÉireann (Ireland's Official Top 40) was first broadcast in 2007.

It has become increasingly common to hear Irish top 40 hits presented in Irish by radio stations normally associated with English: East Coast FM, Flirt FM, Galway Bay FM, LM FM, Midwest Radio, Beat 102 103, Newstalk, Red FM, Spin 1038, Spin South West and Wired FM.

Electric Picnic, a music festival attended by thousands, features DJs from the Dublin-based Irish-language radio station Raidió na Life, as well as celebrities from Irish-language media doing sketches and comedy. Dara Ó Briain and Des Bishop are among the latter, Bishop (an American by origin) having spent a well-publicised year in the Conamara Gaeltacht to learn the language and popularise its use.

Education

Gaeltacht schools

There are 127 Irish-language primary and 29 secondary schools in the Gaeltacht regions, with over 9,000 pupils at primary level and over 3,000 at secondary being educated through Irish. There are also around 1,000 children in Irish language preschools or Naíonraí in the regions.

In Gaeltacht areas education has traditionally been through Irish since the foundation of the state in 1922. A growing number of schools now teach through English, given that the official Gaeltacht boundaries no longer reflect linguistic reality. Even when most students were brought up with Irish, the language was taught only as an L2 (second) language, with English being taught as an L1 (first) language. Professor David Little commented:

..the needs of Irish as L1 at post-primary level have been totally ignored, as at present there is no recognition in terms of curriculum and syllabus of any linguistic difference between learners of Irish as L1 and L2.

In 2015 Minister for Education and Skills Jan O'Sullivan TD announced that there would be a comprehensive change in the instruction and teaching of Irish in Gaeltacht schools which would include an updated curriculum for students and more resources. In 2016 Taoiseach Enda Kenny launched the State Policy on Gaeltacht Education 2017-2022. As a result, new students in most Gaeltacht schools are now taught the language as a new Irish Junior Certificate subject tailored for L1 speakers.[72] It is expected that a new Irish language Leaving Certificate subject for L1 speakers will come into the same schools in 2020. The policy represents a fundamental change in education in the Gaeltacht, and allows schools which teach through English to opt out of being classed as Gaeltacht schools.

Irish-medium education outside the Gaeltacht

There has been rapid growth in a branch of the State-sponsored school system (mostly urban) in which Irish is the language of instruction. Such schools (known as Gaelscoileanna at primary level) are found both in middle-class and disadvantaged areas. Their success is due to limited but effective community support and a professional administrative infrastructure.[73]

In 1972, outside official Irish-speaking areas, there were only 11 such schools at primary level and five at secondary level but as of 2019 there are now 180 Gaelscoileanna at primary level and 31 Gaelcholáistí and 17 Aonaid Ghaeilge (Irish language units within English-medium schools) at second level.[74] These schools educate over 50,000 students and there is now at least one in each of the 32 traditional counties of Ireland. There are also over 4,000 children in Irish-medium preschools or Naíonraí outside the Gaeltacht.

These schools have a high academic reputation, thanks to committed teachers and parents. Their success has attracted other parents who seek good examination performance at a moderate cost. The result has been termed a system of "positive social selection," with such schools giving exceptional access to tertiary education and so to employment - an analysis of "feeder" schools (which supply students to third level institutions) has shown that 22% of the Irish-medium schools sent all their students on to tertiary level, compared to 7% of English-medium schools.[75]

Since September 2017 new students in Irish language-medium secondary schools have been taught a new L1 Irish language subject for their Junior Certificate which is specially designed for schools teaching through Irish. It is expected that a new L1 Irish language subject for Leaving Certificate students in Irish-medium schools will be introduced in 2020.

An Foras Pátrúnachta is the largest patron body of Gaelscoileanna in the Republic of Ireland.

Irish summer colleges

There are 47 Irish-language summer colleges.[76] These supplement the formal curriculum, providing Irish language courses, and giving students the opportunity to be immersed in the language, usually for a period of three weeks. Some courses are college-based but generally make use of host families in Gaeltacht areas under the guidance of a bean an tí for second level students. Students attend classes, participate in sports, art, drama, music, go to céilithe and other summer camp activities through the medium of Irish. As with conventional schools, the Department of Education establishes the boundaries for class size and teacher qualifications. Over 25,000 second level students from all over Ireland attend Irish-language summer colleges in the Gaeltacht every Summer. Irish language summer colleges for second level students in the Gaeltacht are supported and represented at national level by CONCOS. There are also shorter courses for adults and third level students in a number of colleges.

Irish in English-medium schools

The Irish language is a compulsory subject in government-funded schools in the Republic of Ireland and has been so since the early days of the state. At present the language must be studied throughout secondary school, but students need not sit the examination in the final year. It is taught as a second language (L2) at second level, to native (L1) speakers and learners (L2) alike.[77] English is offered as a first (L1) language only, even to those who speak it as a second language. The curriculum was reorganised in the 1930s by Father Timothy Corcoran SJ of UCD, who could not speak the language himself.[78]

In recent years the design and implementation of compulsory Irish have been criticised with growing vigour for their ineffectiveness.[79] In March 2007, the Minister for Education, Mary Hanafin, announced that more attention would be given to the spoken language, and that from 2012 the percentage of marks available in the Leaving Certificate Irish exam would increase from 25% to 40% for the oral component.[80] This increased emphasis on the oral component of the Irish examinations is likely to change the way Irish is examined.[81][82] Despite this, there is still a strong emphasis on the written word at the expense of the spoken, involving analysis of literature and poetry and the writing of lengthy essays and stories in Irish for the (L2) Leaving Certificate examination.

Extra marks of 5–10% marks are awarded to students who take some of their examinations through Irish, though this practice has been questioned by the Irish Equality Authority.[83]

It is possible to gain an exemption from learning Irish on the grounds of time spent abroad or a learning disability, subject to Circular 12/96 (primary education) and Circular M10/94 (secondary education) issued by the Department of Education and Science. In the three years up to 2010 over half the students granted an exemption from studying Irish for the Leaving Certificate because of a learning difficulty sat or intended to sit for other European language examinations such as French or German.[84]

The Royal Irish Academy's 2006 conference on "Language Policy and Language Planning in Ireland" found that the study of Irish and other languages in Ireland was declining. It was recommended, therefore, that training and living for a time in a Gaeltacht area should be compulsory for teachers of Irish. No reference was made to the decline of the language in the Gaeltacht itself. The number of second level students doing "higher level" Irish for the Irish Leaving Certificate increased from 15,937 in 2012 to 23,176 (48%) in 2019.[85][86][87]

Debate concerning compulsory Irish

The abolition of compulsory Irish for the Leaving Certificate has been a policy advocated twice by Fine Gael, a major Irish party which more recently won power in the 2011 general election as part of a coalition with the Labour Party. This policy was the cause of disapproving comment by many Irish language activists before the election.[88]

In 2005 Enda Kenny, leader of Fine Gael, called for the language to be made an optional subject in the last two years of secondary school. Kenny, despite being a fluent speaker himself (and a teacher), stated that he believed that compulsory Irish has done the language more harm than good. The point was made again in April 2010 by Fine Gael's education spokesman Brian Hayes, who said that forcing students to learn Irish was not working, and was actually driving young people away from real engagement with the language. The question provoked a public debate, with some expressing resentment of what they saw as the coercion involved in compulsory Irish.[89] Fine Gael now places primary emphasis on improved teaching of Irish, with greater emphasis on oral fluency rather than the rote learning that characterises the current system.

In 2014 just over 7,000 students chose not to sit their Irish Leaving Cert exams, down from almost 14,000 in 2009.[90]

In 2007 the Government abolished the requirement for barristers and solicitors to pass a written Irish language examination before becoming eligible to commence professional training in the Kings Inns or Blackhall Place. A Government spokesman said it was part of a move to abolish requirements which were no longer practical or realistic.[91] The Bar Council and Law Society run compulsory oral Irish language workshops as part of their professional training courses.

Irish at tertiary level in Ireland

There are third level courses offered in Irish at all universities (UCC, TCD, UCD, DCU, UL, NUIM, NUIG, TUD, UU, QUB) and most also have Irish language departments.

The national Union of Students in Ireland has a full-time Irish language officer. Most universities in the Republic have Irish-language officers elected by the students.

University College Cork (UCC) maintains a unique site where old texts of Irish relevance in several languages, including Irish, are available in a scholarly format for public use.[92]

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland, known in Irish as Tuaisceart Éireann, has no official languages but Irish is recognised as a minority language. According to the 2011 UK Census, in Northern Ireland 184,898 (10.65%) claim to have some knowledge of Irish, of whom 104,943 (6.05%) can speak the language to varying degrees - but it is the home language of just 0.2% of people.(see Irish language in Northern Ireland). Areas in which the language remains a vernacular are referred to as Gaeltacht areas.

There are 36 Gaelscoileanna, two Gaelcholáistí and three Aonaid Ghaeilge (Irish-language units) in English-medium secondary schools in Northern Ireland.

Attitudes towards the language in Northern Ireland traditionally reflect the political differences between its two main communities. The language has been regarded with suspicion by Unionists, who have associated it with the Roman Catholic-majority Republic, and more recently, with the Republican movement in Northern Ireland itself. Many republicans in Northern Ireland, including Sinn Féin President Gerry Adams, learned Irish while in prison, a development known as the Jailtacht.[93] Laws passed by the Parliament of Northern Ireland, and still in force, state that only English could be used in public street signs, but Irish and Ulster Scots are used by businesses with bilingual (Irish/English) and trilingual (Irish/English/Ulster Scots) signage seen.

Irish was taught in Catholic secondary schools (especially by the Christian Brothers) but not taught at all in the controlled sector, mostly attended by Protestant pupils. Irish-medium schools, however, known as Gaelscoileanna, were founded in Belfast and Derry. These schools and the Gaelscoileanna movement has since expanded to across much of Northern Ireland similar to its expansion in the Republic of Ireland. An Irish-language newspaper called Lá (later called Lá Nua) produced by The Andersonstown News Group (later called Belfast Media Group) was also established in Belfast in 1984 and ran as a daily newspaper between 2003 and 2008. The paper is no longer produced due to a decision by Foras na Gaeilge to cease funding it in late 2008. BBC Radio Ulster began broadcasting a nightly half-hour programme in Irish in the early 1980s called Blas ("taste, accent") and BBC Northern Ireland also showed its first TV programme in the language in the early 1990s. BBC Northern Ireland now have an Irish Language Department in their headquarters in Belfast.

In 2006 Raidió Fáilte Northern Ireland's first Irish language community radio station started broadcasting to the Greater Belfast Area and is one of only two Irish language community radio stations on the island of Ireland, the other being Raidió na Life in Dublin. In October 2018 the station moved to a new building on the junction of the Falls Road and the Westlink motorway.[94][95]

The Ultach Trust was established with a view to broadening the appeal of the language among Protestants, although DUP politicians like Sammy Wilson ridiculed it as a "leprechaun language".[96] Ulster Scots, promoted by some loyalists, was, in turn, ridiculed by nationalists and even some Unionists as "a DIY language for Orangemen".[97]

Irish received official recognition in Northern Ireland for the first time in 1998 under the Good Friday Agreement's provisions on "parity of esteem". A cross-border body known as Foras na Gaeilge was established to promote the language in both Northern Ireland and the Republic, taking over the functions of the previous Republic-only Bord na Gaeilge. The Agreement (and subsequent implementation measures and memoranda) also contained specific provisions regarding the availability of the Irish language television service TG4 signal in Northern Ireland. In 2001, the British government ratified the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages in respect to Irish in Northern Ireland. In March 2005, TG4 began broadcasting from the Divis transmitter near Belfast, as a result of an agreement between the Department of Foreign Affairs in the Republic of Ireland and the UK Northern Ireland Office. Following Digital Switchover for terrestrial television transmissions in both parts of Ireland in 2012, TG4 is now carried on Freeview HD for viewers in Northern Ireland (channel 51) as well as to those households in Border areas that have spillover reception of the ROI Saorview platform (channel 104). TG4 also continues to be available on other TV delivery platforms across Northern Ireland: Sky (channel 163) and Virgin Cable customers in Belfast (channel 877).

Belfast City Council has designated the Falls Road area (from Milltown Cemetery to Divis Street) as the Gaeltacht Quarter of Belfast, one of the four cultural quarters of the city. There are a growing number of Irish-medium schools throughout Northern Ireland (e.g. see photo above). Forbairt Feirste work with the business sector across Belfast to promote the Irish language in the business sector and have been very successful in Nationalist areas.

In February 2018 Foras na Gaeilge announced that Belfast and Carn Tóchair in Derry are going to be designated as being two of the first formal Líonraí Gaeilge (Irish Language Networks) outside the Gaeltacht. The other areas to be designated as the first formal Líonraí Gaeilge are Loughrea, Ennis and Clondalkin.

Under the St Andrews Agreement, the UK Government committed to introduce an Irish Language Act. Although a consultation document on the matter was published in 2007, the restoration of devolved government by the Northern Ireland Assembly later that year meant that responsibility for language transferred from London to Belfast. In October 2007, the then Minister of Culture, Arts and Leisure, Edwin Poots MLA announced to the Assembly that he did not intend to bring forward an Irish language Bill. The debate over a proposed Acht na Gaeilge or Irish Language Act has been a central bone of contention between Sinn Féin and the DUP since early 2017 in their efforts to reestablish the Northern Ireland Executive.[98][99]

Outside Ireland

Irish is no longer used as a community language by the Irish diaspora. It is still used, however, by Irish-speaking networks. In Canada such speakers have a gathering place called the Permanent North American Gaeltacht, the only designated Gaeltacht outside Ireland. Irish has retained a certain status abroad as an academic subject. It is also used as a vehicle of journalism and literature. A small number of activists teach and promote the language in countries to which large numbers of Irish have migrated.

Irish is taught as a degree subject in a number of tertiary institutions in North America and northern and eastern Europe, and at the University of Sydney in Australia, while the University of Auckland in New Zealand teaches it as an extension course. It is also an academic subject in several European universities, including Moscow State University.

The organisation Coláiste na nGael[100] plays a major part in fostering the Irish language in Britain. North America has several groups and organisations devoted to the language. Among these are Daltaí na Gaeilge and the North American Gaeltacht. In the Antipodes the main body is the Irish Language Association of Australia, based in Melbourne.[101] The websites maintained by these groups are supplemented by a number of sites and blogs maintained by individuals.

Irish-language publications outside Ireland include two online publications: a quarterly American-based journal called An Gael,[69] and a fortnightly newsletter from Australia called An Lúibín.[102]

Irish at tertiary level internationally

In 2009 the Irish government announced funding for third-level institutions abroad who offer or wish to offer Irish language courses. There are thirty such universities where the Irish language is taught to students. Furthermore, scholarships for international studies in the Irish language can be attained by the Fulbright Commission and Ireland Canada University Foundation.[103][104]

- Great Britain

England:

- St Mary's University College, Twickenham London

- Liverpool

- University of Sheffield

- Cambridge In 2007 the University started offering courses in Modern Irish in addition to Medieval Irish.[105]

Scotland:

Wales:

- Continental Europe

Austria:

Czech Republic:

- Charles University in Prague

France:

Germany:

- Leipzig

- Freiburg

- Bonn

- Berlin

- Halle

- Mannheim

- Marburg

- Ruhr University Bochum

- Scoil Teangacha Nua-Cheilteacha (SKSK)

- Volkshochschule Buxtehude

- Münchner Volkshochschule

Netherlands:

Norway:

Poland:

Sweden:

- Uppsala

Russia:

- Moscow

- North America

Canada:

United States of America:

- Pittsburgh

- Harvard incl. Harvard Extension School

- Berkeley

- Notre Dame

- Wisconsin-Madison

- Marquette

- Arizona

- Marylhurst

- Boston University

- Saint Thomas

- New York University

- Fordham University

- University of St. Thomas (Texas)

- Ireland Institute of Pittsburgh (Pennsylvania)

- Glucksman, Ireland House, New York

- Daltaí na Gaeilge

- University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

- Australia

- Asia

China:

Mobile education

On St. Patrick's Day 2014 the language learning app Duolingo announced the release of its new Irish language learning course. As of April 2018 the course had been downloaded by 4.27 million users and as of early 2019 has 961,000 active learners.[106][107] Data from 2016 showed 53% of learners were from the U.S; 23% were from Ireland; 10% were from the U.K and 5% were from Canada.[108]

In 2016 Irish President Michael D. Higgins lauded the seven volunteers who worked with Duolingo to produce the curriculum, calling their contribution "an act of both national and global citizenship."[108] President Higgins went on to say that he hoped the impact of the Duolingo project would catch the attention of the rest of the Irish Government and boost its confidence in the success of language revitalization efforts.[108]

See also

- Irish language

- Official Languages Act 2003

- Gaeltacht – Irish speaking regions in Ireland.

- Gaeltacht Act 2012

- Údarás na Gaeltachta

- Bailte Seirbhísí Gaeltachta – Gaeltacht Service Towns

- Líonraí Gaeilge – Irish Language Networks

- 20-Year Strategy for the Irish Language 2010-2030

- List of Irish language media

- Gaelscoil – Irish language-medium school

- Gaelcholáiste – Irish language-medium secondary school

- Gaeloideachas

- An Chomhairle um Oideachas Gaeltachta & Gaelscolaíochta

- Irish language in Northern Ireland

- Irish language outside Ireland

- List of organisations in Irish Language Movement

- Scottish Gaelic

References

- Carty, Nicola. "The First Official Language? The status of the Irish language in Dublin" (PDF).

- title="Just 6.3% of Gaeilgeoirí speak Irish on a weekly basis"|publisher=Journal.ie|date=23 November 2017|url=https://www.thejournal.ie/census-irish-education-3712741-Nov2017/%7Caccess-date=14 April 2020

- https://www.cso.ie/en/media/csoie/releasespublications/documents/population/2017/The_Irish_language.pdf

- "The role of the Irish language in Northern Ireland's deadlock". The Economist. 12 April 2017. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- Bratt Paulston, Christina. Linguistic Minorities in Multilingual Settings: Implications for Language Policies. J. Benjamins Pub. Co. p. 81.

- Pierce, David (2000). Irish Writing in the Twentieth Century. Cork University Press. p. 1140.

- Ó hÉallaithe, Donncha (1999). "Native speakers". Cuisle.

- http://www.cso.ie/en/media/csoie/releasespublications/documents/population/2017/7._The_Irish_language.pdf

- "Roghnaítear an Ghaeilge do níos lú ná 1 faoin gcéad de na hidirbhearta ar ATManna Bhanc na hÉireann". Tuairisc.ie. 4 October 2016. Archived from the original on 6 October 2016. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- Irish Gaelic speakers in the United States: https://names.mongabay.com/languages/Irish_Gaelic.html

- Australia, Language spoken at home: https://profile.id.com.au/australia/language

- Language in England and Wales: 2011: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/culturalidentity/language/articles/languageinenglandandwales/2013-03-04

- "Language and Occupational Status: Linguistic Elitism in the Irish Labour Market". The Economic and Social Review. Ideas.repec.org. 40: 435–460. 2009. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- "Beo! - Meán Fómhair 2014". Beo.ie. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- "Irish Language and the Gaeltacht - CSO - Central Statistics Office".

- Brian Ó Broin. "Schism fears for Gaeilgeoirí". Irishtimes.com. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- Interview with Dr John Walsh entitled "Nuachainteoirí," 4 April 2014: Technology.ie: https://technology.ie/nuachainteoiri-podchraoladh/

- "Gach leabhar Gaeilge i gCló - Irish Books". Litriocht.com. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- http://www.cso.ie/en/media/csoie/releasespublications/documents/population/2017/7._The_Irish_language.pdf

- https://web.archive.org/web/20090105154755/http://www.oceanfm.ie/onair/donegalnews.php?articleid=000002629. Archived from the original on 5 January 2009. Retrieved 1 June 2010. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Staidéar Cuimsitheach Teangalaíoch ar Úsáid na Gaeilge sa Ghaeltacht: Piomhthátal agus Moltaí" (PDF). Pobail.ie. 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 February 2011. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- "Nuashonrú ar an Staidéar Cuimsitheach Teangeolaíoch ar Úsáid na Gaeilge sa Ghaeltacht: 2006–2011" (PDF). udaras.ie. 2015. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- Rosita Boland: “Can anybody truthfully say that Irish is a necessary language? I do not like having my national identity pinned to a language I never use and cannot speak,” Irish Times, 30 May 2016: https://www.irishtimes.com/life-and-style/people/broadside-can-anybody-truthfully-say-that-irish-is-a-necessary-language-1.2663495

- Peter Weakliam, “Why Study Irish?”, University Times, November 2015: http://www.universitytimes.ie/2015/11/why-study-irish/

- Gradireland: Careers with Irish: https://gradireland.com/sites/gradireland.com/files/public/english-language.pdf

- "The state has anglicised the Gaeltacht by encouraging the immigration of English-speakers". Homepage.ntlworld.com. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- The Irish Language in a Changing Society: Shaping The Future, p. xxvi.

- "Majority of new Spiddal apartments held for Irish speakers," Irish Times, 12 July 2004: https://www.irishtimes.com/news/majority-of-new-spiddal-apartments-held-for-irish-speakers-1.1148723

- "Govt announces 20-year bilingual strategy - RTÉ News". RTÉ.ie. 19 December 2006. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- Government of Ireland, "Statement on the Irish Language 2006" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 May 2011. (919 KB). Retrieved on 13 October 2007.

- [Translation] The State (Mac Fhearraigh) v. Mac Gamhna (1983) T.É.T.S 29

- Ó Murchú v. Registrar of Companies and the Minister for Industry and Trade [1988] I.R.S.R (1980–1998) 42

- [Translation] Hardiman, J. – Judicial Review – Supreme Court. Ref : Ó Beoláin v.Fahy [2001] 2 I.R. 279

- Charleton J., The High Court,[2009] IEHC 188

- Macken J., The Supreme Court,[2010] IESC 26

- "Finding the muscle to fix our failing education system". Irishtimes.com. 25 January 2011. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- "Plan for optional Leaving Cert Irish". The Irish Times. 2 February 2011.

- "Fixing the education system". The Irish Times. 2 February 2011.

- Letter by Liadh Ní Riada, former MEP and budget coordinator on the EU budgets committee: “Cost of translating EU documents,” Irish Times, 6 September 2017: https://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/letters/cost-of-translating-eu-documents-1.3210283

- http://retro-digital.com/taking-look-irish-language-busting-myths-cool-statistics/

- Anne Cahill, “Gaeilge to become a full working language of the European Union,” Irish Examiner, 9 March 2016: https://www.irishexaminer.com/ireland/gaeilge-to-become-a-full-working-language-of-the-european-union-386308.html

- Éanna Ó Caollaí (22 March 2014). "Tesco puts the fada back into shopping". Irishtimes.com. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- "Get bilingual and get more notice for your local business". Advertiser.ie. 24 October 2013. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- http://www.cso.ie/en/media/csoie/releasespublications/documents/population/2017/7._The_Irish_language.pdf

- "Windows XP Pacáiste Comhéadan Gaeilge" (in Irish). Microsoft. Archived from the original on 9 June 2007. Retrieved 19 June 2007.

- "KDE Irish Gaelic translation". kde.ie. Archived from the original on 4 July 2007. Retrieved 11 July 2007.

- "Firefox in Irish". mozdev.org. Retrieved 19 June 2007.

- "Bogearra den scoth, chomh maith agus a bhí sé ariamh, anois as Gaeilge" (in Irish). openoffice.org. Retrieved 19 June 2007.

- "Dúchas, Daingean Uí Chúis website". Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- "Letterkenny announced as Gaeltacht Service Town - Donegal Now". Archived from the original on 2 March 2018. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- "Ennis Recognised As Líonra Gaeilge- Clare FM". Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- "Irish-speaking areas in north set for official status for first time- The Irish News". Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- "Historical Step for Irish Language Speaking Communities outside of the Gaeltacht- Foras na Gaeilge". Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- "Irish and bilingual names for new residential areas- Near FM (16.4.19)". Near FM.

- "Sunday Times (Ireland) article on Gael-Taca: log in required".

- "Irish Times obituary of Pádraig Ó Cuanacháin (2008) …". The Irish Times.

- "Riomhthionscadal cónaithe Gaeilge / Irish language residential e-project (From 2009) …". Darren J. Prior website.

- "Ar Mhuin na Muice- Near FM". YouTube.

- "Northern Ireland - Irish Language - Blas". BBC.co.uk. 17 October 2014. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- Watson, Iarfhlaith (30 June 2016). "Irish-language broadcasting: history, ideology and identity" (PDF). Media, Culture & Society. 24 (6): 739–757. doi:10.1177/016344370202400601. hdl:10197/5633.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 27 April 2015. Retrieved 7 May 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- http://stakeholders.ofcom.org.uk/binaries/research/cmr/cmr14/NI_2.pdf

- An Bíobla Naofa (Maynooth 1981)

- "Schmidt agus Gatland i mbun na cleasaíochta cheana, ach ní haon cúis mhagaidh an comhtholgadh". Tuairisc.ie.

- 'An Ghaeilge: bás nó beatha?', Derry Journal, 1 November 2013.

- "nuacht.com". Nuacht.com. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- "Comhar Teoranta". Iriscomhar.com. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- "An Gael - Irisleabhar Idirnáisiúnta na Gaeilge". Angaelmagazine.com. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- "NÓS". nos.ie. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- A link is available at Coláiste Lurgan: lurgan.biz.

- "28 October, 2016 - Government Launches Policy on Gaeltacht Education 2017-2022" (Press release).

- "Gaelscoileanna – Irish Medium Education". Gaelscoileanna.ie. 22 February 1999. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- "Scoileanna : Gaelscoileanna – Irish Medium Education". Gaelscoileanna.ie. 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- "Language and Occupational Status: Linguistic Elitism in the Irish Labour Market". The Economic and Social Review. Ideas.repec.org. 40: 446. 2009. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20100125231552/http://www.irishsummercolleges.com/about.htm. Archived from the original on 25 January 2010. Retrieved 3 June 2010. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Language in the Post-Primary Curriculum" (PDF). Ncca.ie. November 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- Professor R. Comerford, Ireland (Hodder Books, London 2003) p145.

- "The University Times | Head-to-Head: The Irish Language Debate". Universitytimes.ie. 21 February 2011. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- Department of Education & Science, 11 March 2007, Minister Hanafin announces increase in marks for Oral Irish to 40% in exams. Retrieved on 13 October 2007.

- Independent, 12 July 2007. Pupils lap up hi-tech learning of Irish. Retrieved on 13 October 2007.

- Learnosity, National Council for Curriculum and Assessment: Ireland Archived 1 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 13 October 2007.

- "Landmark Decision for Leaving Certificate Students with Dyslexia" (Press release). The Equality Authority. 22 November 2006. Archived from the original on 28 December 2013. Retrieved 19 June 2007.

- "Irish exempt students sit for other languages". The Irish Times. 14 April 2010. Retrieved 2 June 2010.

- "More students taking higher level subjects and fewer failing"- The Irish Times 16.8.17".

- "An riachtantas Gaeilge do na coláistí múinteoireachta bainte amach ag 88% de dhaltaí Ardteiste"- Tuairisc.ie 18.8.18".

- "Number of candidates at each level and breakdown of candidates by grade awarded in each subject- State Examinations Commission Leaving Cert. (2017-2019) 16.8.17" (PDF).

- Donncha Ó hÉallaithe Donncha Ó hÉallaithe. "Beo! - Litir Oscailte Chuig Enda Kenny T.D". Beo.ie. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- "Ultach " 'Compulsory' Irish". Irishtimes.com. 15 April 2010. Archived from the original on 18 July 2012. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- "More is more as number of students taking Irish and science increase". The Irish Times. 13 August 2014.

- "Compulsory Irish rule to be lifted for lawyers". Irish Independent. 21 November 2007.

- "CELT: The online resource for Irish history, literature and politics". Ucc.ie. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- Allen Feldman. Formations of Violence: The Narrative of the Body and Political Terror in Northern Ireland.U of Chicago P, 1991. Chapter 3.

- "'NÍL FOIRGNEAMH RAIDIÓ NÍOS FEARR IN ÉIRINN' Raidió Fáilte ag craoladh ó stiúideo úrnua- NÓS". Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- "Raidió Fáilte in 2018- Raidió na Life & Near FM podcast". Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- "Unionist fear of Irish must be overcome". newshound.com, quoting Irish News. 6 February 2003. Retrieved 19 June 2007.

- "The rich heritage of Ulster Scots culture". newshound.com, quoting Irish News. 16 November 2002. Retrieved 19 June 2007.

- "Northern Ireland Assembly divided by Irish language". BBC News Northern Ireland. 28 June 2017.

- "SF/DUP impasse over substantive issues remains as NI talks adjourn". RTÉ News. 27 June 2017.

- "Irish language in Britain and London". Colaiste-na-ngael.com. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20110711062635/http://www.gaeilgesanastrail.com/. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 3 June 2010. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Cumann Gaeilge na hAstráile". Gaeilgesanastrail.com. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- "Ireland Canada University Foundation". Icuf.ie. 17 October 2013. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20131113065345/http://www.gaeilge.ie/The_Irish_Language/The_Irish_Language_Abroad.asp. Archived from the original on 13 November 2013. Retrieved 6 July 2013. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Irish becomes subject at Cambridge University". BreakingNews.ie. 5 January 2007. Retrieved 19 June 2007.

- "Duolingo website register".

- "Tweet by Duolingo on St. Patricks Day 2018".

- "Ar fheabhas! President praises volunteer Duolingo translators". The Irish Times. Retrieved 14 June 2017.