Ulster Irish

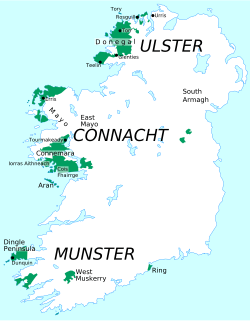

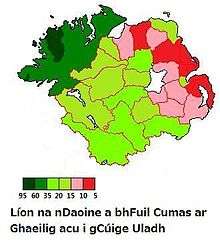

Ulster Irish (Scots: Ulstèr Erse, Irish: Canúint Uladh) is the variety of Irish spoken in the province of Ulster. It "occupies a central position in the Gaelic world made up of Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man".[1] Ulster Irish thus has more in common with Scottish Gaelic and Manx. Within Ulster there have historically been two main sub-dialects: West Ulster and East Ulster. The Western dialect is spoken in County Donegal and once was in parts of neighbouring counties, hence the name Donegal Irish. The Eastern dialect was spoken in most of the rest of Ulster and northern parts of counties Louth and Meath.[1]

History

Ulster Irish was the main language spoken in Ulster from the earliest recorded times even before Ireland became a jurisdiction in the 1300s. Since the Plantation, Ulster Irish was steadily replaced by English. The Eastern dialect died out in the 20th century, but the Western lives on in the Gaeltacht region of County Donegal. In 1808, County Down natives William Neilson and Patrick Lynch (Pádraig Ó Loingsigh) published a detailed study on Ulster Irish. Both Neilson and his father were Ulster-speaking Presbyterian ministers. When the recommendations of the first Comisiún na Gaeltachta were drawn up in 1926, there were regions qualifying for Gaeltacht recognition in the Sperrins and the northern Glens of Antrim and Rathlin Island. The report also makes note of small pockets of Irish speakers in northwest County Cavan, southeast County Monaghan, and the far south of County Armagh. However, these small pockets vanished early in the 20th century while Ulster Irish in the Sperrins survived until the 1950s and in the Glens of Antrim until the 1970s. The last native speaker of Rathlin Irish died in 1985.

Lexicon

The Ulster dialect contains many words not used in other dialects—of which the main ones are Connacht Irish and Munster Irish—or used otherwise only in northeast Connacht. The standard form of Irish is An Caighdeán Oifigiúil. In other cases, a semantic shift has resulted in quite different meanings attaching to the same word in Ulster Irish and in other dialects. Some of these words include:

- ag déanamh is used to mean "to think" as well as "to make" or "to do", síleann, ceapann and cuimhníonn is used in other dialects, as well as in Ulster Irish.

- amharc or amhanc (West Ulster), "look" (elsewhere amharc, breathnaigh and féach; this latter means rather "try" or "attempt" in Ulster)

- barúil "opinion", southern tuairim - in Ulster, tuairim is most typically used in the meaning "approximate value", such as tuairim an ama sin "about that time". Note the typically Ulster derivatives barúlach and inbharúla "of the opinion (that...)".

- bealach, ród "road" (southern and western bóthar and ród (cf. Scottish Gaelic rathad, Manx raad), and bealach "way"). Note that bealach alone is used as a preposition meaning "towards" (literally meaning "in the way of": d'amharc sé bealach na farraige = "he looked towards the sea"). In the sense "road", Ulster Irish often uses bealach mór ("big road") even for roads that aren't particularly big or wide.

- bomaite, "minute" (elsewhere nóiméad, nóimint, neómat, etc., and in Mayo Gaeltacht areas a somewhat halfway version between the northern and southern versions, is the word "móiméad", also probably the original, from which the initial M diverged into a similar nasal N to the south, and into a similar bilabial B to the north.)

- cá huair, "when?" (Connacht cén uair; Munster cathain, cén uair)

- caidé (cad é) atá?, "what is?" (Connacht céard tá; Munster cad a thá, cad é a thá, dé a thá, Scottish Gaelic dé tha)

- cál, "cabbage" (southern gabáiste; Scottish Gaelic càl)

- caraidh, "weir" (Connacht cara, standard cora)

- cluinim, "I hear" (southern cloisim, but cluinim is also attested in South Tipperary and is also used in Achill and Erris in North and West Mayo). In fact, the initial c- tends to be lenited even when it is not preceded by any particle (this is because there was a leniting particle in Classical Irish: do-chluin yielded chluin in Ulster)

- doiligh, "hard"-as in difficult (southern deacair), crua "tough"

- druid, "close" (southern and western dún; in other dialects druid means "to move in relation to or away from something", thus druid ó rud = to shirk, druid isteach = to close in) although druid is also used in Achill and Erris

- eallach, "cattle" (southern beithíoch = "one head of cattle", beithígh = "cattle", "beasts")

- eiteogaí, "wings" (southern sciatháin)

- fá, "about, under" (standard faoi, Munster fé, fí and fá is only used for "under"; mar gheall ar and i dtaobh = "about"; fá dtaobh de = "about" or "with regard to")

- falsa, "lazy" (southern and western leisciúil, fallsa = "false, treacherous") although falsa is also used in Achill and Erris

- faoileog, "seagull" (standard faoileán)

- fosta, "also" (standard freisin)

- Gaeilg, Gaeilig, Gaedhlag, Gaeilic, "Irish" (standard and Western Gaeilge, Southern Gaoluinn, Manx Gaelg, Scottish Gaelic Gàidhlig) although Gaeilg is used in Achill and was used in parts of Erris and East Connacht

- geafta, "gate" (standard geata)

- gairid, "short" (southern gearr)

- gamhain, "calf" (southern lao and gamhain) although gamhain is also used in Achill and Erris

- gasúr, "boy" (southern garsún; garsún means "child" in Connemara)

- girseach, "girl" (southern gearrchaile and girseach)

- gnóitheach, "busy" (standard gnóthach)

- inteacht, an adjective meaning "some" or "certain" is used instead of the southern éigin. Áirithe also means "certain" or "particular".

- mothaím is used to mean "I hear, perceive" as well as "I feel" (standard cloisim) but mothaím generally refers to stories or events. The only other place where mothaím is used in this context is in the Irish of Dún Caocháin and Ceathrú Thaidhg in Erris but it was a common usage throughout most of northern and eastern Mayo, Sligo, Leitrim and North Roscommon

- nighean, "daughter" (standard iníon; Scottish Gaelic nighean)

- nuaidheacht, "news" (standard nuacht, but note that even Connemara has nuaíocht)

- sópa, "soap" (standard gallúnach, Connemara gallaoireach)

- stócach, "youth", "young man", "boyfriend" (Southern = "gangly, young lad")

- tábla, "table" (western and southern bord and clár, Scottish Gaelic bòrd)

- tig liom is used to mean "I can" as opposed to the standard is féidir liom or the southern tá mé in ann. Tá mé ábalta is also a preferred Ulster variant. Tig liom and its derivatives are also commonly used in the Irish of Joyce Country, Achill and Erris

- the word iontach "wonderful" is used as an intensifier instead of the prefix an- used in other dialects.

Words generally associated with the now dead East Ulster Irish include:[1]

- airigh (feel, hear, perceive) - but also known in more southern Irish dialects

- ársuigh, more standardized ársaigh (tell) - but note the expression ag ársaí téamaí "telling stories, spinning yearns" used by the modern Ulster writer Séamus Ó Grianna.

- coinfheasgar (evening)

- corruighe, more standardized spelling corraí (anger)

- frithir (sore)

- go seadh (yet)

- márt (cow)

- práinn (hurry)

- toigh (house)

- tonnóg (duck)

In other cases, a semantic shift has resulted in quite different meanings attaching to the same word in Ulster Irish and in other dialects. Some of these words include:

- cloigeann "head" (southern and western ceann; elsewhere, cloigeann is used to mean "skull")

- capall "mare" (southern and western láir; elsewhere, capall means "horse")

Phonology

The phonemic inventory of Ulster Irish (based on the dialect of Gweedore[2]) is as shown in the following chart (see International Phonetic Alphabet for an explanation of the symbols). Symbols appearing in the upper half of each row are velarized (traditionally called "broad" consonants) while those in the bottom half are palatalized ("slender"). The consonants /h, n, l/ are neither broad nor slender.

| Consonant phonemes |

Labial | Coronal | Dorsal | Glottal | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilabial | Labio- dental |

Labio- velar |

Dental | Alveolar | Alveolo- palatal |

Palatal | Velar | |||||||||||

| Plosive | pˠ pʲ | bˠ bʲ |

t̪ˠ | d̪ˠ |

ṯʲ | ḏʲ |

c | ɟ |

k | ɡ |

||||||||

| Fricative/ Approximant |

fˠ fʲ | vʲ |

w |

sˠ | ʃ | ç | j |

x | ɣ |

h | ||||||||

| Nasal | mˠ mʲ |

n̪ˠ |

n | ṉʲ |

ɲ |

ŋ |

||||||||||||

| Tap | ɾˠ ɾʲ |

|||||||||||||||||

| Lateral approximant |

l̪ˠ |

l | ḻʲ |

|||||||||||||||

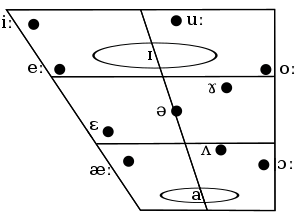

The vowels of Ulster Irish are as shown on the following chart. These positions are only approximate, as vowels are strongly influenced by the palatalization and velarization of surrounding consonants.

The long vowels have short allophones in unstressed syllables and before /h/.

In addition, Ulster has the diphthongs /ia, ua, au/.

Some characteristics of the phonology of Ulster Irish that distinguish it from the other dialects are:

- The only broad labial continuant is the approximant [w]. In other dialects, fricative [vˠ] is found instead of or in addition to [w]. No dialect makes a phonemic contrast between the approximant and the fricative, however.

- There is a three-way distinction among coronal nasals and laterals: /n̪ˠ ~ n ~ ṉʲ/, /l̪ˠ ~ l ~ ḻʲ/ as there is in Scottish Gaelic, and there is no lengthening or diphthongization of short vowels before these sounds and /m/. Thus, while ceann "head" is /cɑːn/ in Connacht and /caun/ in Munster, in Ulster it is /can̪ˠ/ (compare Scottish Gaelic /kʲaun̪ˠ/

- /ɔː/ corresponds to the /oː/ of other dialects. The Ulster /oː/ corresponds to the /au/ of other dialects.

- Long vowels are shortened when in unstressed syllables.

- /n/ is realized as [r] (or is replaced by /r/) after consonants other than [s]. This happens in Connacht and Scottish Gaelic as well.

- Orthographic -adh in unstressed syllables is always [u] (this includes verb forms), as it is in the Scottish Gaelic dialect of Cowal and most of Sutherland.[3]

- Unstressed orthographic -ach is pronounced [ax], [ah], or [a].

- According to Ó Dochartaigh (1987), the loss of final schwa "is a well-attested feature of Ulster Irish". This has led to words like fada being pronounced [fˠad̪ˠ].[4]

Differences between the Western and Eastern sub-dialects of Ulster include the following:

- In West Ulster and most of Ireland, the vowel written ea is pronounced [a] (e.g. fear [fʲaɾˠ]), but in East Ulster it is pronounced [ɛ] (e.g. fear /fʲɛɾˠ/ as it is in Scottish Gaelic (/fɛɾ/). J. J. Kneen comments that Scottish Gaelic and Manx generally follow the East Ulster pronunciation. The name Seán is pronounced [ʃɑːnˠ] in Munster and [ʃæːnˠ] in West Ulster, but [ʃeːnˠ] in East Ulster, whence anglicized spellings like Shane O'Neill and Glenshane.[1]

- In East Ulster, th or ch in the middle of a word tends to vanish and leave one long syllable. William Neilson wrote that this happens "in most of the counties of Ulster, and the east of Leinster".[1]

- In East Ulster, /x/ at the end of words (as in loch) tends to be much weaker. For example, amach may be pronounced [əˈmˠæ] and bocht pronounced [bˠɔt̪ˠ]. Neilson wrote that this is found "in all the country along the sea coast, from Derry to Waterford".[1]

- Neilson wrote that the "ancient pronunciation" of broad bh and mh as [vˠ], especially at the beginning or end of a word "is still retained in the North of Ireland, as in Scotland, and the Isle of Man", whereas "throughout Connaught, Leinster and some counties of Ulster, the sound of [w] is substituted". However, broad bh or mh may become [w] in the middle of a word (for example in leabhar).[1]

Morphology

Initial mutations

Ulster Irish has the same two initial mutations, lenition and eclipsis, as the other two dialects and the standard language, and mostly uses them the same way. There is, however, one exception: in Ulster, a dative singular noun after the definite article is lenited (e.g. ar an chrann "on the tree") (as is the case in Scottish and Manx), whereas in Connacht and Munster, it is eclipsed (ar an gcrann), except in the case of den, don and insan, where lenition occurs in literary language. Both possibilities are allowed for in the standard language.

Verbs

Irish verbs are characterized by having a mixture of analytic forms (where information about person is provided by a pronoun) and synthetic forms (where information about number is provided in an ending on the verb) in their conjugation. In Ulster and North Connacht the analytic forms are used in a variety of forms where the standard language has synthetic forms, e.g. molann muid "we praise" (standard molaimid, muid being a back formation from the verbal ending -mid and not found in the Munster dialect, which retains sinn as the first person plural pronoun as do Scottish Gaelic and Manx) or mholfadh siad "they would praise" (standard mholfaidís). The synthetic forms, including those no longer emphasised in the standard language, may be used in short answers to questions.

The 2nd conjugation future stem suffix in Ulster is -óch- (pronounced [ah]) rather than -ó-, e.g. beannóchaidh mé [bʲan̪ˠahə mʲə] "I will bless" (standard beannóidh mé [bʲanoːj mʲeː]).

Some irregular verbs have different forms in Ulster from those in the standard language. For example:

- (gh)níom (independent form only) "I do, make" (standard déanaim) and rinn mé "I did, made" (standard rinne mé)

- tchíom [t̠ʲʃiːm] (independent form only) "I see" (standard feicim, Southern chím, cím (independent form only))

- bheiream "I give" (standard tugaim, southern bheirim (independent only)), ní thabhram or ní thugaim "I do not give" (standard only ní thugaim), and bhéarfaidh mé/bheirfidh mé "I will give" (standard tabharfaidh mé, southern bhéarfad(independent form only))

- gheibhim (indpependent form only) "I get" (standard faighim), ní fhaighim "I do not get"

- abraim "I say, speak" (standard deirim, ní abraim "I do not say, speak", although deir is used to mean "I say" in a more general sense.)

Particles

In Ulster the negative particle cha (before a vowel chan, in past tenses char - Scottish Gaelic/Manx chan, cha do) is sometimes used where other dialects use ní and níor. The form is more common in the north of the Donegal Gaeltacht. Cha cannot be followed by the future tense: where it has a future meaning, it is followed by the habitual present. It triggers a "mixed mutation": /t/ and /d/ are eclipsed, while other consonants are lenited. In some dialects however (Gweedore), cha eclipses all consonants, except b- in the forms of the verb "to be", and sometimes f- :

| Ulster | Standard | English |

|---|---|---|

| Cha dtuigim | Ní thuigim | "I don't understand" |

| Chan fhuil sé/Cha bhfuil sé | Níl sé (contracted from ní fhuil sé) | "He isn't" |

| Cha bhíonn sé | Ní bheidh sé | "He will not be" |

| Cha phógann muid/Cha bpógann muid | Ní phógaimid | "We do not kiss" |

| Chan ólfadh siad é | Ní ólfaidís é | "They wouldn't drink it" |

| Char thuig mé thú | Níor thuig mé thú | "I didn't understand you" |

In the Past Tense, some irregular verbs are lenited/eclipsed in the Interrogative/Negative that differ from the standard, due to the various particles that may be preferred :-

| Interrogative | Negative | English |

|---|---|---|

| An raibh tú? | Cha raibh mé | "I was not" |

| An dtearn tú? | Cha dtearn mé | "I did not do, make" |

| An dteachaigh tú? | Cha dteachaigh mé | "I did not go" |

| An dtáinig tú? | Cha dtáinig mé | "I did not come" |

| An dtug tú? | Cha dtug mé | "I did not give" |

| Ar chuala tú? | Char chuala mé | "I did not hear" |

| Ar dhúirt tú? | Char dhúirt mé | "I did not say" |

| An bhfuair tú? | Chan fhuair mé | "I did not get" |

| Ar rug tú? | Char rug mé | "I did not catch, bear" |

| Ar ith tú? | Char ith mé | "I did not eat" |

| Ar chígh tú/An bhfaca tú? | Chan fhaca mé | "I did not see" |

Syntax

The Ulster dialect uses the present tense of the subjunctive mood in certain cases where other dialects prefer to use the future indicative:

- Suigh síos anseo aige mo thaobh, a Shéimí, go dtugaidh (dtabhairidh, dtabhraidh) mé comhairle duit agus go n-insidh mé mo scéal duit.

- Sit down here by my side, Séimí, till I give you some advice and tell you my story.

The verbal noun can be used in subordinate clauses with a subject different from that of the main clause:

- Ba mhaith liom thú a ghabháil ann.

- I would like you to go there.

Music

Some notable Irish singers who sing songs in the Ulster Irish dialect include Kneecap, Lillis Ó Laoire, Maighread Ní Dhomhnaill, Mairéad Ní Mhaonaigh and Pádraigín Ní Uallacháin.

Literature

Notable Ulster Irish writers include Micí Mac Gabhann, Seosamh Mac Grianna, Peadar Toner Mac Fhionnlaoich, Cosslett Ó Cuinn, Niall Ó Dónaill, Séamus Ó Grianna, Brian Ó Nualláin, Colette Ní Ghallchóir and Cathal Ó Searcaigh.

See also

- Ulster Scots dialects

- Mid Ulster English

- Scottish Gaelic

- Irish language in Northern Ireland

References

- Ó Duibhín, Ciarán. The Irish Language in County Down. Down: History & Society. Geography Publications, 1997. pp.15-16

- Ní Chasaide, Ailbhe (1999). "Irish". Handbook of the International Phonetic Association. Cambridge University Press. pp. 111–16. ISBN 0-521-63751-1.

- Ó Broin, Àdhamh. "Essay on Dalriada Gaelic" (PDF). Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- PlaceNames NI: Townland of Moyad Upper

Basic Irish Conversation and Grammar by A.J. Hughes (Ben Madigan Press) Book & 2 CDs in the Ulster dialect

Irish day by day A.J. Hughes book & 2 CDs in Ulster dislect

Published literature

- ‘AC FHIONNLAOICH, Seán: Scéal Ghaoth Dobhair. Foilseacháin Náisiúnta Teoranta, Baile Átha Cliath 1981 (stair áitiúil) Gaoth Dobhair

- MAC A’ BHAIRD, Proinsias: Cogar san Fharraige. Scéim na Scol in Árainn Mhóir, 1937-1938. Coiscéim, Baile Átha Cliath 2002 (béaloideas) Árainn Mhór

- MAC CIONAOITH, Maeleachlainn: Seanchas Rann na Feirste - Is fann guth an éin a labhras leis féin. Coiscéim, Baile Átha Cliath 2005 (béaloideas) Rann na Feirste

- MAC CUMHAILL, Fionn (= Mánus): Na Rosa go Brách. An Gúm, Baile Átha Cliath 1997 (úrscéal) Na Rosa

- Slán Leat, a Mhaicín. Úrscéal do Dhaoine Óga. An Gúm, Baile Átha Cliath 1998 (úrscéal) Na Rosa

- Gura Slán le m’Óige. Oifig an tSoláthair, Baile Átha Cliath 1974 (úrscéal) Na Rosa

- MAC GABHANN, Micí: Rotha Mór an tSaoil. Seán Ó hEochaidh a scríobh, Proinsias Ó Conluain a chuir in eagar. Cló IarChonnachta, Indreabhán 1996/1997 (dírbheathaisnéis) Ulaidh

- MAC GIOLLA DOMHNAIGH, Gearóid agus Gearóid STOCKMAN (Eag.): Athchló Uladh. Comhaltas Uladh, Béal Feirste 1991 (béaloideas) Oirthear Uladh: Aontroim, Reachrainn

- MAC GRIANNA, Seosamh: An Druma Mór. An Gúm, Baile Átha Cliath 1991 (úrscéal) Na Rosa

- Pádraic Ó Conaire agus Aistí Eile. An Gúm, Baile Átha Cliath 1986 (aistí) Na Rosa

- Dá mBíodh Ruball ar an Éan. An Gúm, Baile Átha Cliath 1992 (úrscéal gan chríochnú) Na Rosa

- Mo Bhealach Féin. An Gúm, Baile Átha Cliath 1997 (dírbheathaisnéis) Na Rosa

- MAC MEANMAN, Seán Bán: An Chéad Mhám. Coiscéim, Baile Átha Cliath 1990 (gearrscéalta) Lár Thír Chonaill

- An Dara Mám. Coiscéim, Baile Átha Cliath 1991 (gearrscéalta) Lár Thír Chonaill

- An Tríú Mám. Coiscéim, Baile Átha Cliath 1992 (aistí) Lár Thír Chonaill

- Cnuasach Céad Conlach. Coiscéim, Baile Átha Cliath 1989 (béaloideas) Lár Thír Chonaill

- McGLINCHEY, CHARLES: An Fear Deireanach den tSloinneadh. Patrick Kavanagh a bhreac síos. Eag. Desmond Kavanagh agus Nollaig Mac Congáil. Arlen House, Gaillimh 2002 (dírbheathaisnéis) Inis Eoghain

- NIC AODHÁIN, Medhbh Fionnuala (Eag.): Báitheadh iadsan agus tháinig mise. Coiscéim, Baile Átha Cliath 1993 (finscéalta) Tír Chonaill

- NIC GIOLLA BHRÍDE, Cáit: Stairsheanchas Ghaoth Dobhair. Coiscéim, Baile Átha Cliath 1996/1997 (seanchas, béaloideas, cuimhní cinn) Na Rosa

- Ó BAOIGHILL, Pádraig: An Coileach Troda agus scéalta eile. Coiscéim, Baile Átha Cliath 1993 (gearrscéalta) Na Rosa

- Óglach na Rosann. Coiscéim, Baile Átha Cliath 1994 (beathaisnéis) Na Rosa

- Cuimhní ar Dhochartaigh Ghleann Fhinne. Coiscéim, Baile Átha Cliath 1994 (aistí beathaisnéise) Na Rosa

- Nally as Maigh Eo. Coiscéim, Baile Átha Cliath 1998 (beathaisnéis) Na Rosa

- Gaeltacht Thír Chonaill - Ó Ghleann go Fánaid. Coiscéim, Baile Átha Cliath 2000 (seanchas áitiúil) Na Rosa

- Srathóg Feamnaí agus Scéalta Eile. Coiscéim, Baile Átha Cliath 2001 (gearrscéalta) Na Rosa

- Ceann Tìre/Earraghàidheal. Ár gComharsanaigh Ghaelacha. Coiscéim, Baile Átha Cliath 2003 (leabhar taistil)

- Amhráin Hiúdaí Fheidhlimí agus Laoithe Fiannaíochta as Rann na Feirste. Pádraig Ó Baoighill a chuir in eagar, Mánus Ó Baoill a chóirigh an ceol. Preas Uladh, Muineachán 2001

- Gasúr Beag Bhaile na gCreach. Coiscéim, Baile Átha Cliath 2004

- (Eag.) Faoi Scáth na Mucaise. Béaloideas Ghaeltachtaí Imeallacha Thír Chonaill. Coiscéim, Baile Átha Cliath 2005

- Ó BAOILL, Dónall P. (Eag.):Amach as Ucht na Sliabh, Imleabhar 1. Cumann Staire agus Seanchais Ghaoth Dobhair i gcomhar le Comharchumann Forbartha Ghaoth Dobhair. Gaoth Dobhair 1992 (béaloideas) Gaoth Dobhair

- …Imleabhar 2. Cumann Staire agus Seanchais Ghaoth Dobhair i gcomhar le Comharchumann Forbartha Gh. D. Gaoth Dobhair 1996 (béaloideas) Gaoth Dobhair

- Ó COLM, Eoghan: Toraigh na dTonn. Cló IarChonnachta, Indreabhán 1995 (cuimhní cinn, stair áitiúil) Toraigh/Machaire an Rabhartaigh

- Ó DONAILL, Eoghan: Scéal Hiúdaí Sheáinín. An Gúm, Baile Átha Cliath 1997 (beathaisnéis agus béaloideas) Na Rosa

- Ó DONAILL, Niall: Na Glúnta Rosannacha. Oifig an tSoláthair, Baile Átha Cliath 1974 (stair áitiúil) Na Rosa

- Seanchas na Féinne. An Gúm, Baile Átha Cliath 1998 (miotaseolaíocht) Na Rosa

- Ó GALLACHÓIR, Pádraig: Seachrán na Mic Uí gCorra. Coiscéim, Baile Átha Cliath 2008 (úrscéal)

- Ó GALLCHÓIR, Tomás: Séimidh agus scéalta eile. Coiscéim, Baile Átha Cliath 1996 Na Rosa

- Ó GRIANNA, Séamus (= “Máire”): Caisleáin Óir. Cló Mercier, Baile Átha Cliath 1994 (úrscéal) Na Rosa

- Castar na Daoine ar a Chéile. Scríbhinní Mháire 1. Eagarthóir: Nollaig Mac Congáil. Coiscéim, Baile Átha Cliath 2002 (úrscéal, altanna) Na Rosa

- Cith is Dealán. Cló Mercier, Baile Átha Cliath agus Corcaigh 1994 (gearrscéalta) Na Rosa

- Cora Cinniúna 1-2. An Gúm, Baile Átha Cliath 1993 (gearrscéalta) Na Rosa

- Cúl le Muir agus scéalta eile. Oifig an tSoláthair, Baile Átha Cliath 1961 (gearrscéalta) Na Rosa

- Na Blianta Corracha. Scríbhinní Mháire 2. Eagarthóir: Nollaig Mac Congáil. Coiscéim, Baile Átha Cliath 2003 (altanna) Na Rosa

- Nuair a Bhí Mé Óg. Cló Mercier, Baile Átha Cliath agus Corcaigh 1986 (dírbheathaisnéis) Na Rosa

- An Sean-Teach. Oifig an tSoláthair, Baile Átha Cliath 1968 (úrscéal) Na Rosa

- Tairngreacht Mhiseoige. An Gúm, Baile Átha Cliath 1995 (úrscéal) Na Rosa

- Ó LAIGHIN, Donnchadh C.: An Bealach go Dún Ulún. Scéalta Seanchais agus Amhráin Nuachumtha as Cill Charthaigh. Cló Iar-Chonnachta, Indreabhán, Conamara 2004 Cill Charthaigh

- Ó SEARCAIGH, Cathal: Seal i Neipeal. Cló Iar-Chonnachta, Indreabhán, Conamara 2004 (leabhar taistil) Gort an Choirce

- Ó SEARCAIGH, Séamus: Beatha Cholm Cille. An Gúm, Baile Átha Cliath 1997 Na Rosa

- Laochas - Scéalta as an tSeanlitríocht. An Gúm, Baile Átha Cliath 1945/1984/1996 (miotaseolaíocht) Na Rosa

- ÓN tSEANAM ANALL - Scéalta Mhicí Bháin Uí Bheirn. Mícheál Mac Giolla Easbuic a chuir in eagar. Cló Iar-Chonnachta, Indreabhán, Conamara 2008. Cill Chárthaigh

- SCIAN A CAITHEADH LE TOINN Scéalta agus amhráin as Inis Eoghain agus cuimhne ar Ghaeltacht Iorrais. Cosslett Ó Cuinn a bhailigh, Aodh Ó Canainn agus Seosamh Watson a chóirigh. Coiscéim, Baile Átha Cliath 1990 (béaloideas) Tír Eoghain

- UA CNÁIMHSÍ, Pádraig: Idir an Dá Ghaoth. Sáirséal Ó Marcaigh, Baile Átha Cliath 1997 (stair áitiúil) Na Rosa

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Gaelic resources focusing on Ulster Irish (in Irish)

- A yahoogroup for learners of Ulster Irish

- Oideas Gael (based in Sliabh Liag)