Primitive Irish

Primitive Irish or Archaic Irish[1] (Irish: Gaeilge Ársa) is the oldest known form of the Goidelic languages. It is known only from fragments, mostly personal names, inscribed on stone in the ogham alphabet in Ireland and western Great Britain from around the 4th to the 7th or 8th centuries.[2]

| Primitive Irish | |

|---|---|

| Archaic Irish | |

Ogham stone from Ratass Church, 6th century AD. It reads: [A]NM SILLANN MAQ VATTILLOGG ("name of Sílán son of Fáithloga") | |

| Native to | Ireland, Isle of Man, western coast of Britain |

| Region | Ireland and Britain |

| Era | Evolved into Old Irish about the 6th century AD |

Indo-European

| |

| Ogham | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | pgl |

| Glottolog | None |

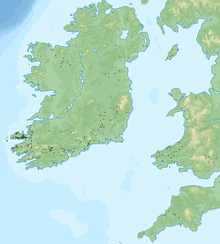

Map with original locations of orthodox ogham inscriptions already found. | |

Characteristics

Transcribed ogham inscriptions, which lack a letter for /p/, show Primitive Irish to be similar in morphology and inflections to Gaulish, Latin, Classical Greek and Sanskrit. Many of the characteristics of modern (and medieval) Irish, such as initial mutations, distinct "broad" and "slender" consonants and consonant clusters, are not yet apparent.

More than 300 ogham inscriptions are known in Ireland, including 121 in County Kerry and 81 in County Cork, and more than 75 found outside Ireland in western Britain and the Isle of Man, including more than 40 in Wales, where Irish colonists settled in the 3rd century, and about 30 in Scotland, although some of these are in Pictish. Many of the British inscriptions are bilingual in Irish and Latin; however, none show any sign of the influence of Christianity or Christian epigraphic tradition, suggesting they date from before 391, when Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire. Only about a dozen of the Irish inscriptions show any such sign.

The majority of ogham inscriptions are memorials, consisting of the name of the deceased in the genitive case, followed by MAQI, MAQQI, "of the son" (Modern Irish mic), and the name of his father, or AVI, AVVI, "of the grandson", (Modern Irish uí) and the name of his grandfather: for example DALAGNI MAQI DALI, "[the stone] of Dalagnos son of Dalos". Sometimes the phrase MAQQI MUCOI, "of the son of the tribe", is used to show tribal affiliation. Some inscriptions appear to be border markers.[3]

Grammar

The brevity of most orthodox ogham inscriptions makes it difficult to analyse the archaic Irish language in depth, but it is possible to understand the basis of its phonology and the rudiments of its nominal morphology.[4]

Nominal morphology

With the exception of a few inscriptions in the singular dative, two in the plural genitive and one in the singular nominative, most known inscriptions of nouns in orthodox ogham are found in the singular genitive, so it is difficult to fully describe their nominal morphology. The German philologist Sabine Ziegler, however, drawing parallels with reconstructions of the Proto-Celtic language morphology (whose nouns are classified according to the vowels that characterize their endings), limited the archaic Irish endings of the singular genitive to -i, -as, -os and -ais.

The first ending, -i, is found in words equivalent to the Proto-Celtic o-stem nouns. This category was also registered in the dative as -u, with a possible occurrence of the use of the nominative, also in -u. -os, in turn, is equivalent to Proto-Celtic i-stems and u-stems, while -as corresponds to ā-stems. The exact function of -ais remains unclear.[5]

Furthermore, according to Damian Mcmanus, Proto-Celtic nasal, dental, and velar stems also correspond to the Primitive Irish -as genitive, attested in names such as Glasiconas [6], Cattubuttas [7], and Lugudeccas[8].

Phonology

It is possible, through comparative study, to reconstruct a phonemic inventory for the properly attested stages of the language using comparative linguistics and the names used in the scholastic tradition for each letter of the ogham alphabet, recorded in the Latin alphabet in later manuscripts.[9][10]

Vowels

There is a certain amount of obscurity in the vowel inventory of Primitive Irish: while the letters Ailm, Onn and Úr are recognized by modern scholars as /a/, /o/ and /u/, there is some difficulty in reconstructing the values of Edad and Idad. [11] They are poorly attested, probably an artificial pair, just like peorð and cweorð of the futhorc, but probably have the respective pronunciations of /e/ and /i/. [12] There were also two diphthongs, written as ai and oi.[13]

In later stages of the language, scholastic oghamist traditions incorporated five new letters for vowels, called forfeda, corresponding to digraphs of the orthodox spelling, but these no longer corresponded to Primitive Irish sounds. [14]

Consonants

The consonant inventory of Primitive Irish is reconstructed by celtologist Damian McManus as follows:[15][16]

| Bilabial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Labiovelar[lower-alpha 1] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ||||||||

| Stop | b[lower-alpha 2] | t | d | k | ɡ | kʷ | ɡʷ | |||

| Fricative[lower-alpha 3] | s, st [lower-alpha 4] | |||||||||

| Approximant | j[lower-alpha 5] | w | ||||||||

| Lateral | l | |||||||||

| Trill | r | |||||||||

The letters Cért, Gétal and Straif, respectively transliterated as q, ng (or gg) and z, were known by the ancient scholastic oghamists as foilceasta (questions) due to the obsolescence of their original pronunciations: the first two, /kʷ/ and /gʷ/, had merged with plain velars in Old Irish, and the third, probably /st/, merged with /s/.[17][18] However, evidence of the original distinction between Straif and Sail was still present into the Old Irish period, as the séimhiú (lenition) of /s/ produced /f/ for lexemes with original Straif but /h/ for lexemes with original Sail.[19]

The letter Úath or hÚath, transliterated as h, although not counted among the foilceasta, also presented particular difficulties due to apparently being a silent letter. It was probably pronounced as /j/ in an early stage of Primitive Irish, disappearing before the transition to Old Irish.[20]

Transition to Old Irish

Old Irish, written from the 6th century onward, has most of the distinctive characteristics of Irish, including "broad" and "slender" consonants, initial mutations, some loss of inflectional endings, but not of case marking, and consonant clusters created by the loss of unstressed syllables, along with a number of significant vowel and consonant changes, including the presence of the letter p, reimported into the language via loanwords and names.

As an example, a 5th-century king of Leinster, whose name is recorded in Old Irish king-lists and annals as Mac Caírthinn Uí Enechglaiss, is memorialised on an ogham stone near where he died. This gives the late Primitive Irish version of his name (in the genitive case), as MAQI CAIRATINI AVI INEQAGLAS.[21] Similarly, the Corcu Duibne, a people of County Kerry known from Old Irish sources, are memorialised on a number of stones in their territory as DOVINIAS.[22] Old Irish filed, "poet (gen.)", appears in ogham as VELITAS.[23] In each case the development of Primitive to Old Irish shows the loss of unstressed syllables and certain consonant changes.

These changes, traced by historical linguistics, are not unusual in the development of languages but appear to have taken place unusually quickly in Irish. According to one theory given by John T. Koch,[21] these changes coincide with the conversion to Christianity and the introduction of Latin learning. All languages have various registers or levels of formality, the most formal of which, usually that of learning and religion, changes slowly while the most informal registers change much more quickly, but in most cases are prevented from developing into mutually unintelligible dialects by the existence of the more formal register. Koch argues that in pre-Christian Ireland the most formal register of the language would have been that used by the learned and religious class, the druids, for their ceremonies and teaching. After the conversion to Christianity the druids lost their influence, and formal Primitive Irish was replaced by the then Upper Class Irish of the nobility and Latin, the language of the new learned class, the Christian monks. The vernacular forms of Irish, i.e. the ordinary Irish spoken by the upper classes (formerly 'hidden' by the conservative influence of the formal register) came to the surface, giving the impression of having changed rapidly; a new written standard, Old Irish, established itself.

References

| For a list of words relating to Primitive Irish, see the Primitive Irish language category of words in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- In Old Irish, these consonants had disappeared. The stops merged with their simple velar counterparts, while /w/ became /f/.

- The sound /p/ was absent in Primitive Irish, but a letter in scholastic ogham was created for the late introduction of this sound, called Pín, Ifín or Iphín, the only forfeda with a consonant value, although often used as an equivalent to the digraphs io, ía and ia in Latin spelling. In early loanwords, the Latin letter P was incorporated as Q, for example Primitive Irish QRIMITIR from Latin presbyter.

- The fricatives /f, v, θ, ð, x, ɣ, h, and β̃/ emerged by the 5th century with the advent of phonetic séimhiú (lenition). In turn, their non-lenited counterparts occasionally and inconsistently became geminates.

- The sound /s/ in scholastic ogham was represented by two letters: Sail and Straif, the latter probably representing a previously distinct sound such as /st/ or /sw/. However, the two sounds had likely merged by the Old Irish period, except in their respective lenited forms.

- Lost in later stages.

- Koch, John T. (2006). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 986–1390. ISBN 978-1-85109-440-0.

- Edwards, Nancy (2006). The Archaeology of Early Medieval Ireland. Routledge. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-415-22000-2.

- Rudolf Thurneysen, A Grammar of Old Irish, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1946, pp. 9–11; Dáibhí Ó Cróinín, Early Medieval Ireland 400–1200, Longman, 1995, pp. 33–36, 43; James MacKillop, Dictionary of Celtic Mythology, Oxford University Press, 1998, pp. 309–310

- Stifler 2010 p.56

- Ziegler 1994 p.53-92

- McManus 1991 p.102

- McManus 1991 p.108

- McManus 1991 p.116

- Stifler 2010 p.56

- McManus 1991 p.38-39

- McManus 1991 pp.36-38

- McManus 1988 pp.163-165

- Stifler 2010 p.58

- McManus 1991 pp.141-146

- McManus 1991 pp.36-39

- Stifler 2010 p.58

- McManus 1991 p.182

- Ziegler 1994 pp.11-12

- Stifler 2006 p.30

- McManus 1991 pp.36-37

- John T. Koch, "The conversion and the transition from Primitive to Old Irish", Emania 13, 1995

- Dáibhí Ó Cróinín, Early Medieval Ireland 400–1200, Longman, 1995, p. 44

- Rudolf Thurneysen, A Grammar of Old Irish, p. 58-59

Bibliography

- Carney, James (1975), "The Invention of the Ogom Cipher", Ériu, Dublin: Royal Irish Academy, 26: 53–65, ISSN 0332-0758

- Conroy, Kevin (2008), Celtic initial consonant mutations – nghath and bhfuil?, Boston: Boston College, hdl:2345/530

- Eska, Joseph (2009) [1993], "The Emergence of the Celtic Languages", in Martin J. Ball; Nicole Müller (eds.), The Celtic Languages, London/New York: Routledge, pp. 22–27, ISBN 978-0415422796

- Fanning, T.; Ó Corráin, D. (1977), "An Ogham stone and cross-slab from Ratass church", Journal of the Kerry Archaeological and Historial Society, Tralee (10): 14–8, ISSN 0085-2503

- Harvey, Anthony (1987), "The Ogam Inscriptions and Their Geminate Consonant Symbols", Ériu, Dublin: Royal Irish Academy, 38: 45–71, ISSN 0332-0758

- Jackson, Kenneth (1953), Language and history in early Britain: a chronological survey of the Brittonic languages 1st to 12th c. A.D., Edimburgo: Edinburgh University Press

- Koch, John (2006), Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia, ISBN 1851094407, retrieved 14 February 2018

- Koch, John (1995), "The Conversion of Ireland and the Emergence of the Old Irish Language, AD 367–637", Emania, Navan Resarch Group (13): 39–50, ISSN 0951-1822, retrieved 15 February 2018

- MacKillop, James (1998), Dictionary of Celtic Mythology, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0198691572

- McManus, Damian (1983), "A chronology of the Latin loan-words in Early Irish", Ériu, Dublin: Royal Irish Academy, 34: 21–71, ISSN 0332-0758

- McManus, Damian (1991), "A Guide to Ogam", Maynooth Monographs, Maynooth: An Sagart (4), ISBN 1870684176

- McManus, Damian (1988), "Irish letter-names and their kennings", Ériu, Dublin: Royal Irish Academy, 39: 127–168, ISSN 0332-0758

- Nancy, Edwards (2006), The Archaeology of Early Medieval Ireland, Abingdon: Routledge, ISBN 9780415220002

- Ó Cróinín, Dáibhí (1995), "Early Medieval Ireland 400–1200", Longman History of Ireland, Harlow: Longman, ISBN 0582015650, retrieved 15 February 2018

- Richter, Michael (2005), "Medieval Ireland: The Enduring Tradition", New Gill History of Ireland, London: Gill & MacMillan (1), ISBN 0717132935, retrieved 20 February 2018

- Schrijver, Peter (2015), "Pruners and trainers of the Celtic family tree: The rise and development of Celtic in the light of language contact", Proceedings of the XIV International Congress of Celtic Studies, Maynooth University 2011, Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, pp. 191–219, ISBN 978-1855002296

- Stifter, David (2009) [1993], "Early Irish", in Martin J. Ball; Nicole Müller (eds.), The Celtic Languages, London/New York: Routledge, pp. 55–116, ISBN 978-0415422796

- Stifter, David (2006), Sengoidelc: Old Irish For Beginners, Syracuse,NY: Syracuse University Press, p. 30, ISBN 978-0815630722

- Stokes, Whitley (2002) [1886], "Celtic Declension", in Daniel Davis (ed.), The development of Celtic linguistics, 1850-1900, 5, New York: Routledge, ISBN 0415226996

- Thurneysen, Rudolf (1946), A Grammar of Old Irish, Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies

- Ziegler, Sabine (1994) [1991], Die Sprache der altirischen Ogam-Inschriften, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN 3525262256, retrieved 16 February 2018