Celtiberian language

Celtiberian or Northeastern Hispano-Celtic is an extinct Indo-European language of the Celtic branch spoken by the Celtiberians in an area of the Iberian Peninsula between the headwaters of the Douro, Tagus, Júcar and Turia rivers and the Ebro river. This language is directly attested in nearly 200 inscriptions dated to the 2nd and 1st centuries BC, mainly in Celtiberian script, a direct adaptation of the northeastern Iberian script, but also in the Latin alphabet. The longest extant Celtiberian inscriptions are those on three Botorrita plaques, bronze plaques from Botorrita near Zaragoza, dating to the early 1st century BC, labelled Botorrita I, III and IV (Botorrita II is in Latin). In the northwest was another Celtic language, Gallaecian (also known as Northwestern Hispano-Celtic), that was closely related to Celtiberian. It is the only known Celtic language not to be classed as Nuclear Celtic [3].

| Celtiberian | |

|---|---|

| Northeastern Hispano-Celtic | |

| Native to | Iberian Peninsula |

| Ethnicity | Celtiberians |

| Extinct | attested 2nd to 1st century BC[1] |

| Celtiberian script | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | xce |

xce | |

| Glottolog | celt1247[2] |

Celtiberian in the context of the Paleohispanic languages | |

Overview

Enough has been preserved to show that the Celtiberian language could be called Q-Celtic (like Goidelic), and not P-Celtic like Gaulish.[4] For some, this has served to confirm that the legendary invasion of Ireland by the Milesians, preserved in the Lebor Gabála Érenn, actually happened.

Some scholars believe that Brythonic is more closely related to Goidelic than to Gaulish;[5] it would follow that the P/Q division is polyphyletic, the change from kʷ to p occurring in Brythonic and Gaulish at a time when they were already separate languages, rather than constituting a division that marked a separate branch in the "family tree" of the Celtic languages. A change from PIE kʷ (q) to p also occurred in some Italic languages and Ancient Greek dialects: compare Oscan pis, pid ("who, what?") with Latin quis, quid; or Gaulish epos ("horse") and Attic Greek ἵππος hippos with Latin equus and Mycenaean Greek i-qo. Celtiberian and Gaulish are usually grouped together as the Continental Celtic languages, but this grouping is paraphyletic too: no evidence suggests the two shared any common innovation separately from Insular Celtic.

Celtiberian exhibits a fully inflected relative pronoun ios (as does, e.g., Ancient Greek), not preserved in other Celtic languages, and the particles -kue 'and' < *kʷe (cf. Latin -que, Attic Greek τε te), nekue 'nor' < *ne-kʷe (cf. Latin neque), ekue 'also, as well' < *h₂et(i)-kʷe (cf. Lat. atque, Gaulish ate, OIr. aith 'again'), ve "or" (cf. Latin enclitic -ve and Attic Greek ἤ ē < Proto-Greek *ē-we). As in Welsh, there is an s-subjunctive, gabiseti "he shall take" (Old Irish gabid), robiseti, auseti. Compare Umbrian ferest "he/she/it shall make" or Ancient Greek δείξῃ deiksēi (aorist subj.) / δείξει deiksei (future ind.) "(that) he/she/it shall show".

Phonology

Celtiberian was a Celtic language that shows the characteristic sound changes of Celtic languages such as:[6]

PIE Consonants

- PIE *bʰ, *dʰ, *gʰ > b, d, g: Loss of Proto-Indo-European voiced aspiration.

- Celtiberian and Gaulish placename element -brigā 'hill, town, akro-polis' < *bʰr̥ǵʰ-eh₂;

- nebintor 'they are watered' < *nebʰ-i-nt-or;

- dinbituz 'he must build' < *dʰingʰ-bī-tōd, ambi-dingounei 'to build around > to enclose' < *h₂m̥bi-dʰingʰ-o-mn-ei (cf. Latin fingō 'to build, shape' < *dʰingʰ-o, Old Irish cunutgim 'erect, build up' < *kom-ups-dʰingʰ-o), ambi-diseti '(that someone) builds around > enclose' < *h₂m̥bi-dʰingʰ-s-e-ti.

- gortika 'mandatory, required' < *gʰor-ti-ka (cfr. Latin ex-horto 'exhort' < *ex-gʰor-to);

- duatir 'daughter' < *dʰugh₂tēr, duateros 'grandson, son of the daughter' (Common Celtic duxtir);

- bezom 'mine' < *bʰedʰ-yo 'that is pierced'.

- PIE *kʷ > ku: Celtiberian changed the PIE voiceless labiovelar kʷ to ku (hence Q-Celtic), a development also observed in Old Irish and Latin. On the contrary Brythonic or P-Celtic (as well as Greek and some Italic branches like Osco-Umbrian) changed kʷ to p. -kue 'and' < *kʷe', Latin -que, Osco-Umbrian -pe 'and', neip 'and not, neither' < *ne-kʷe.

- PIE *ḱw > ku: ekuo horse (in ethnic name ekualakos) < *h₁eḱw-ālo (cf. Middle Welsh ebawl 'foal' < *epālo, Latin equus 'horse', OIr. ech 'horse' < *eko´- < *h₁eḱwo-, OBret. eb < *epo- < *h₁eḱwo-);

- kū 'dog' < *kuu < *kwōn, in Virokū, 'hound-man, male hound/wolf, werewolf' (cfr. Old Irish Ferchú < *Virokū, Old Welsh Gurcí < *Virokū 'idem.'.[7]

- PIE *gʷ > b: bindis 'legal agent' < *gʷiHm-diks (cfr. Latin vindex 'defender');[8]

- bovitos 'cow passage' < *gʷow-(e)ito (cfr. OIr bòthar 'cow passage' < *gʷow-(e)itro),[9] and boustom 'cowshed' < *gʷow-sto.

- PIE *gʷʰ > gu: guezonto < *gʷʰedʰ-y-ont 'imploring, pleading'. Common Celtic *guedyo 'ask, plead, pray', OIr. guidid, W. gweddi.

- PIE *p- > *φ- > ∅: Loss of PIE *p, e.g. *ro- (Celtiberian, Old Irish and Old Breton) vs. Latin pro- and Sanskrit pra-. ozas sues acc. pl. fem. 'six feet, unit of measure' (< *φodians < *pod-y-ans *sweks);

- aila 'stone building' < *pl̥-ya (cfr. OIr. ail 'boulder');

- vamos 'higher' < *uφamos < *up-m̥os;

- vrantiom 'remainder, rest' < *uper-n̥tiyo (cfr. Latin (s)uperans).

- Toponym Litania now Ledaña 'broad place' < *pl̥th2-ny-a.

Consonant clusters

- PIE *mn > un: as in Lepontic, Brittonic and Gaulish, but not Old Irish and seemingly not Galatian. Kouneso 'neighbour' < *kom-ness-o < *Kom-nedʰ-to (cf. OIr. comnessam 'neighbour' < *Kom-nedʰ-t-m̥o).

- PIE *pn > un: Klounia < *kleun-y-a < *kleup-ni 'meadow' (Cfr. OIr. clúain 'meadow' < *klouni). However, in Latin *pn > mn: damnum 'damage' < *dHp-no.

- PIE *nm > lm: Only in Celtiberian. melmu < *men-mōn 'intelligence', Melmanzos 'gifted with mind' < *men-mn̥-tyo (Cfr. OIr. menme 'mind' < *men-mn̥. Also occurs in modern Spanish: alma 'soul' < *anma < Lat. anima, Asturian galmu 'step' < Celtic *kang-mu.

- PIE *ps > *ss / s: usabituz 'he must excavate (lit. up/over-dig)' < *ups-ad-bʰiH-tōd, Useizu * < *useziu < *ups-ed-yō 'highest'. The ethnic name contestani in Latin (contesikum in native language), recall the proper name Komteso 'warm-hearted, friendly' (< *kom-tep-so, cf. OIr. tess 'warm' > *tep-so). In Latin epigraphy that sound its transcript with geminated: Usseiticum 'of the Usseitici' < *Usseito < *upse-tyo. However, in Gaulish and Brittonic *ps > *x (cf. Gaulish Uxama, MW. uchel, 'one six').

- PIE *pt > *tt / t: setantu 'seventh' (< *septmo-to). However in Gaulish and Insular Celtic *pt > x: sextameto 'seventh', Old Irish sechtmad (< *septmo-e-to).

- PIE *gs > *ks > *ss / s: sues 'six' < *sweks;

- Desobriga 'south/right city' (Celts oriented looking east) < *dekso-*bʰr̥ǵʰa; **'Nertobris 'strength town' < *h₂ner-to-*bʰr̥ǵʰs;

- es- 'out of, not' < *eks < *h₁eǵʰs (cf. Lat. ex-, Common Celtic exs-, OIr. ess-). In Latin epigraphy that sound its transcript with geminated: Suessatium < *sweks- 'the sixth city' (cfr. Latin Sextantium)[10]

- Dessicae < *deks-ika. However, in Gaulish *ks > *x: Dexivates.

- PIE *gt > *kt > *tt / t: ditas 'constructions, buildings' < *dʰigʰ-tas (= Latin fictas);

- loutu 'load' < *louttu < *louktu < *leugʰ-tu;

- litom 'it is permitted', ne-litom 'it is not permitted' (< *l(e)ik-to, cf. Latin licitum < *lik-e-to). But Common Celtic *kt > *xt: luxtu < *louktu < *leugʰ-tu, OIr. lucht.

- Celtiberian Retugenos 'right born, lawful' < *h₃reg-tō-genos, Gaulish Rextugenos. In Latin epigraphy that sound its transcript with geminated: Britto 'noble' < *brikto < *bʰr̥ǵʰ-to.

- Bruttius 'fruitful' < *bruktio < *bʰruHǵ-t-y-o (cfr. Latin Fructuosus 'profitable').

- PIE *st > *st: against Gaulish, Irish and Welsh (where the change was *st > ss) preservation of the PIE cluster *st. Gustunos 'excellent' < *gustu 'excellence' < *gus-tu. Old Irish gussu 'excellence' (cfr. Fergus < *viro-gussu), Gaulish gussu (Lezoux Plate, line 7).

Vowels

- PIE *e, *h₁e > e: Togoitei eni 'in Togotis' < *h₁en-i (cf. Lat. in, OIr. in 'into, in'), somei eni touzei 'inside of this territory', es- 'out of, not' < *eks < *h₁eǵʰs (cf. Lat. ex-, Common Celtic exs-, OIr. ess-), esankios 'not enclosed, open' lit. 'unfenced' < *h₁eǵʰs-*h₂enk-yos, treba 'settlement, town', Kontrebia 'conventus, capital' < *kom-treb-ya (cf. OIr. treb, W. tref 'settlement'), ekuo horse < *h₁ekw-os, ekualo 'horseman'.

- PIE *h₂e > a: ankios 'fenced, enclosed' < *h₂enk-yos, Ablu 'strong' < *h₂ep-lō 'strength', augu 'valid, firm' < *h₂ewg-u, adj. 'strong, firm, valid'.

- PIE *o, *Ho > o: olzui (dat.sing.) 'for the last' (< *olzo 'last' < *h₂ol-tyo, cf. Lat. ultimus < *h₂ol-t-m̥o. OIr. ollam 'master poet' < *oltamo < *h₂ol-t-m̥), okris 'mountain' (< *h₂ok-r-i, cf. Lat. ocris 'mountain', OIr. ochair 'edge' < *h₂ok-r-i), monima 'memory' (< *monī-mā < *mon-eye-mā).

- PIE *eh₁ > ē > ī?. This Celtic reflex isn't well attested in Celtiberian. e.g. IE *h3rēg'-s meaning "king, ruler" vs. Celtiberian -reiKis, Gaulish -rix, British rix, Old Irish, Old Welsh, Old Breton ri meaning "king". In any case, the maintenance of PIE ē = ē is well attested in dekez 'he did' < *deked < *dʰeh₁k-et, identical to Latin fecit.

- PIE *eh₂ > ā: dāunei 'to burn' < *deh₂u-nei (Old Irish dóud, dód 'burn' < *deh₂u-to-), silabur sāzom 'enough money, a considerable amount of money' (< *sātio < *she₂t-yo, Common Celtic sāti 'sufficiency', OIr. sáith), kār 'friendship' (< *keh₂r, cf. Lat. cārus 'dear' < *keh₂r-os, Irish cara 'friend', W. caru 'love' < *kh₂r-os).

- PIE *eh₃, *oH > a/u: Celtic *ū in final syllables and *ā in non-final syllables, e.g. IE *dh3-tōd to Celtiberian datuz meaning 'he must give'. dama 'sentence' < *dʰoh₁m-eh₂ 'put, dispose' (cfr. Old Irish dán 'gift, skill, poem', Germanic dōma < *dʰoh₁m-o 'verdict, sentence').

- PIE *Hw- > w-: uta 'conj. and, prep. besides' (< *h₂w-ta, 'or, and', cfr, Umb. ute 'or', Lat. aut 'or' (< *h₂ew-ti).

Syllabic resonants and laryngeals

- PIE *n̥ > an / *m̥ > am: arganto 'silver' < *h₂r̥gn̥to (cf. OIr. argat and Latin argentum). kamanom 'path, way' *kanmano < *kn̥gs-mn̥-o (cf. OIr. céimm, OW. cemmein 'step'), decameta 'tithe' < *dekm̥-et-a (cf. Gaulish decametos 'tenth', Old Irish dechmad 'tenth'), dekam 'ten' (cf. Lat. decem, Common Celtic dekam, OIr. deich < *dekm̥), novantutas 'the nine tribes', novan 'nine' < *h₁newn̥ (cf. Lat. novem, Common Celtic novan, OW. nauou < *h₁newn̥), ās 'we, us' (< *ans < *n̥s, Old Irish sinni < *sisni, *snisni 'we, us', cf. German uns < *n̥s), trikanta < *tri-kn̥g-ta, lit. 'three horns, three boundaries' > 'civil parish, shire' (modern spanish Tres Cantos.

- Like Common Celtic and Italic (SCHRIJVER 1991: 415, McCONE 1996: 51 and SCHUMACHER 2004: 135), PIE *CHC > CaC (C = any consonant, H = any laringeal): datuz < *dh₃-tōd, dakot 'they put' < *dʰh₁k-ont, matus 'propitious days' < *mh₂-tu (latin mānus 'good' < *meh₂-no, Old Irish maith 'good' < *mh₂-ti).

- PIE *CCH > CaC (C = any consonant, H = any laringeal): Magilo 'prince' (< *mgh₂-i-lo, cf. OIr. mál 'prince' < *mgh₂-lo).

- PIE *r̥R > arR and *l̥R > alR (R = resonant): arznā 'part, share' < *φarsna < *parsna < *pr̥s-nh₂. Common Celtic *φrasna < *prasna < *pr̥s-nh₂, cf. Old Irish ernáil 'part, share'.

- PIE *r̥P > riP and *l̥P > liP (P = plosive): briganti PiRiKanTi < *bʰr̥ǵʰ-n̥ti. silabur konsklitom 'silver coined' < *kom-skl̥-to 'to cut'.

- PIE *Cr̥HV > CarV and *Cl̥HV > CalV: sailo 'dung, slurry' *salyo < *sl̥H-yo (cf. Lat. saliva < *sl̥H-iwa, OIr. sal 'dirt' < *sl̥H-a), aila 'stone building' < *pl̥-ya (cf. OIr. ail 'boulder'), are- 'first, before' (Old Irish ar 'for', Gaulish are 'in front of', < *pr̥h₂i. Lat. prae- 'before' < *preh₂i).

- Like Common Celtic (JOSEPH 1982: 51 and ZAIR 2012: 37), PIE *HR̥C > aRC (H = any laringeal, R̥ any syllabic resonant, C = any consonant): arganto 'silver' < *h₂r̥gn̥to, not **riganto.

Exclusive developments

- Affrication of the PIE groups -*dy-, -*dʰy-. -*ty- > z/th (/θ/) located between vowels and of -*d, -*dʰ > z/th (/θ/) at the end of the word: adiza 'duty' < *adittia < *h₂ed-d(e)ik-t-ya; Useizu 'highest' < *ups-ed-yō; touzu 'territory' < *teut-yō; rouzu 'red' < *reudʰy-ō; olzo 'last' < *h₂ol-tyo; ozas 'feet' < *pod-y-ans; datuz < *dh₃-tōd; louzu 'free' (in: LOUZOKUM, MLH IV, K.1.1.) < *h₁leudʰy-ō (cf. Oscan loufir 'free man', Russian ljúdi 'men, people'.

Morphology

Noun cases[11][12]

- arznā 'part, share' < *parsna < *pr̥s-nh₂. Common Celtic *φrasna < *prasna

- veizos 'witness' < *weidʰ-yo < *weidʰ- 'perceive,see' / vamos 'higher' < *up-m̥os

- gentis 'son, descendance' < *gen-ti. Common Celtic *genos 'family'

- loutu 'load' < *louttu < *louktu < *leugʰ-tu. Common Celtic luxtu < *louktu < *leugʰ-tu (oir. lucht).

- duater 'daughter' < *dʰugh₂tēr. Common Celtic duxtir.

| Case | Singular | Plural | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ā-stem | o-stem | i-stem | u-stem | r-stem | ā-stem | o-stem | i-stem | u-stem | r-stem | ||

| Nominative | *arznā | *veizos / *vamos (n. *-om) | *gentis | *loutus | *duater | *arznās / *arznī | *veizoi (n *-a) | *gentis | *loutoves | *duateres | |

| Accusative | *arznām | *veizom | *gentim | *loutum | *duaterem | *arznās < -*ams | *veizus < *-ōs < -*oms | *gentīs < -*ims | *loutūs < -*ums | *duaterēs < -*ems | |

| Genitive | *arznās | *veizo | *gentes[13] | ? | *duateros | *arznaum | *veizum < *weidʰ-y-ōm | *gentizum < *isōm | *loutoum < *ewōm | ? | |

| Dative | *arznāi | *veizūi < *weidʰ-y-ōi | *gentei | *loutuei[14] | ? | ? | *veizubos | ? | ? | ? | |

| Ablative | *arznaz[15] | *veizuz < *weidʰ-y-ōd / *vamuz < *up-m̥ōd | *gentiz | *loutuez | *duaterez < -*ed | ? | *veizubos | ? | ? | ? | |

| Locative | *arznai | *veizei | *gentei | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | |

There is also a potential Vocative case, however this is very poorly attested, with only an ambiguous -e ending for o-stem nouns being cited in literature.

Demonstrative pronouns[16]

| Case | Singular | Plural | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| masculine | feminine | neuter | masculine | feminine | neuter | ||

| Nominative | *so: so viros 'this man' | *sa: sa duater 'this daughter' | *soz: soz bezom < *so-d *bʰedʰ-yom 'this mine'. | *sos < *so-s ? | *sas < *sa-s ? | *soizos < so-syos < *so-sy-os ? | |

| Accusative | *som: 'to this' | *sam: 'to this' | *sozom < *so-sy-om? | *sus < *sōs < *so-ms | *sās < *sa-ms | *soizus < so-syōs < *so-sy-oms ?? | |

| Genitive | ? | ? | ? | soum < *so-ōm 'of these' | saum < *sa-ōm 'of these' | soizum < *so-sy-ōm 'of these' | |

| Dative | somui < *so-sm-ōi 'for this' | somai < *so-sm-ai 'for this' | ? | ? | ? | ? | |

| Locative | somei < *so-sm-ei 'from this' | samei < *sa-sm-ei 'from this' | ? | ? | ? | ? | |

Sample texts

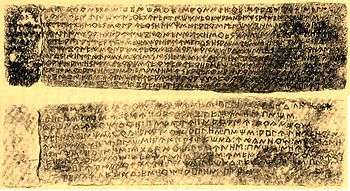

- First Botorrita plaque side A, Botorrita, Saragossa. (K.01.01.A).

- trikantam : bergunetakam : togoitos-kue : sarnikio (:) kue : sua : kombalkez : nelitom

- nekue [: to-ver-daunei : litom : nekue : daunei : litom : nekue : masnai : dizaunei : litom : soz : augu

- aresta[lo] : damai : uta : oskues : stena : verzoniti : silabur : sleitom : konsklitom : gabizeti

- kantom [:] sanklistara : otanaum : togoitei : eni : uta : oskuez : boustom-ve : korvinom-ve

- makasiam-ve : ailam-ve : ambidiseti : kamanom : usabituz : ozas : sues : sailo : kusta : bizetuz : iom

- asekati : [a]mbidingounei : stena : es : vertai : entara : tiris : matus : dinbituz : neito : trikantam

- eni : oisatuz : iomui : listas : titas : zizonti : somui : iom : arznas : bionti : iom : kustaikos

- arznas : kuati : ias : ozias : vertatosue : temeiue : robiseti : saum : dekametinas : datuz : somei

- eni touzei : iste : ankios : iste : esankios : uze : areitena : sarnikiei : akainakubos

- nebintor : togoitei : ios : vramtiom-ve : auzeti : aratim-ve : dekametam : datuz : iom : togoitos-kue

- sarnikio-kue : aiuizas : kombalkores : aleites : iste : ires : ruzimuz : Ablu : ubokum

- soz augu arestalo damai [17]

- all this (is) valid by order of the competent authority

- 'all this' soz (< *sod) 'final, valid' augo (< *h₂eug-os 'strong, valid', cf. Latin augustus 'solemn').

- 'of the competent authority' arestalos (< *pr̥Hi-steh₂-lo 'competent authority' < *pr̥Hi-sto 'what is first, authority', gen. sing.)

- 'by order' damai (< *dʰoh₁m-eh₂ 'stablishing, dispose', instrumental fem. sing.).

- (Translation: Prosper 2006)

- saum dekametinas datuz somei eni touzei iste ankios iste es-ankios

- of these, he will give the tax inside of this territory, so be fenced as be unfenced

- 'of these' (saum < *sa-ōm) 'the tithes, the tax' (dekametinas)

- 'he will pay, will give' (datuz) 'inside, in' (eni < *h₁en-i)

- 'of this' (somei loc. sing. < *so-sm-ei 'from this')

- 'territory' (touzei loc. sing. < *touzom 'territory' < *tewt-yo)

- 'so (be) fenced' iste ankios 'as (be) unfenced' iste es-ankios

- (Transcription Jordán 2004)

- togoitei ios vramtiom-ve auzeti aratim-ve dekametam datuz

- In Togotis, he who draws water either for the green or for the farmland, the tithe (of their yield) he shall give

- (Translation: De Bernardo 2007)

- Great inscription from Peñalba de Villastar, Teruel. (K.03.03).

- eni Orosei

- uta Tigino tiatunei

- erecaias to Luguei

- araianom komeimu

- eni Orosei Ekuoisui-kue

- okris olokas togias sistat Luguei tiaso

- togias

- eni Orosei uta Tigino tiatunei erecaias to Luguei araianom comeimu eni Orosei Ekuoisui-kue okris olokas togias sistat Luguei

- in Orosis and the surroundings of Tigino river, we dedicate the fields to Lugus. In Orosis and Equeiso the hills, the vegetable gardens and the houses are dedicated to Lugus

- 'in' eni (< *h₁en-i) 'Orosis' Orosei (loc. sing. *oros-ei)

- 'and' uta(conj. cop.) 'of Tigino (river)' (gen. sing. *tigin-o) 'in the surroundings' (loc. sing. *tiatoun-ei < *to-yh₂eto-mn-ei)

- 'the furrows > the land cultivated' erekaiās < *perka-i-ans acc. pl. fem.) 'to Lugus' to Luguei

- araianom (may be a verbal complement: properly, totally, *pare-yanom, cfr. welsh iawn) 'we dedicate' komeimu (< *komeimuz < *kom-ei-mos-i, present 3 p.pl.)

- 'in' eni 'Orosis' (Orosei loc. sing.) 'in Ekuoisu' (Ekuoisui loc. sing.) '-and' (-kue <*-kʷe)

- 'the hills' (okris < *h₂ok-r-eyes. nom. pl.) 'the vegetable gardens' (olokas < *olkās < *polk-eh₂-s, nom. pl.) '(and) the roofs > houses' (togias < tog-ya-s, nom. pl.)

- 'are they (dedicated)' sistat (< *sistant < *si-sth₂-nti, 3 p.pl.) 'to Lug' (Lugue-i dat.)

- (Transcription: Meid 1994, Translation: Prosper 2002[18])

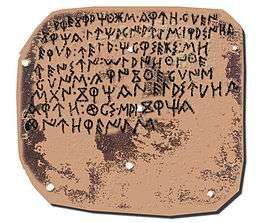

- Bronze plaque of Torrijo del Campo, Teruel.

- kelaunikui

- derkininei : es

- kenim : dures : lau

- ni : olzui : obakai

- eskenim : dures

- useizunos : gorzo

- nei : lutorikum : ei

- subos : adizai : ekue : kar

- tinokum : ekue : lankikum

- ekue : tirtokum : silabur

- sazom : ibos : esatui

- Lutorikum eisubos adizai ekue Kartinokum ekue Lankikum ekue Tirtokum silabur sazom ibos esatui (datuz)

- for those of the Lutorici included in the duty, and also of the Cartinoci, of the Lancici and of the Tritoci, must give enough money to settle the debt with them.

- 'for those included ' (eisubos < *h1epi-s-o-bʰos)

- 'of the Lutorici' (lutorikum gen. masc. pl.)

- 'and also' (ekue <*h₂et(i)kʷe) 'of the Cartinoci' (kartinokum)

- 'and also' (ekue) 'of the Lancici' (lankikum) 'and also' (ekue) 'of the Tritoci' (tirtokum)

- 'in the assignment, in the duty' (adizai loc. fem. sing. < *adittia < *ad-dik-tia. Cfr. Latin addictio 'assignment'),

- 'money' (silabur) 'enough' (sazom < *sātio < *seh₂t-yo)

- 'to settle the debt' (esatui < *essato < *eks-h₂eg-to. Cfr. Latin ex-igo 'demand, require' and exactum 'identical, equivalent')

- 'for them' (ibus < *i-bʰos, dat.3 p.pl.)

- 'must give' (datuz < *dh₃-tōd).

- (Transcription and Translation: Prosper 2015)

Cortono plaque. Unknown origin.

Cortono plaque. Unknown origin. Luzaga plaque (Guadalajara).

Luzaga plaque (Guadalajara)..jpg)

.jpg) Fröhner tessera. Unknown origin.

Fröhner tessera. Unknown origin.

See also

- Celtiberian script

- Botorrita plaque

- Gallaecian language

- Gaulish language

- Lepontic language

- Iberian scripts

- Continental Celtic languages

- Pre-Roman peoples of the Iberian Peninsula

- Lusitanian language

References

- Celtiberian at MultiTree on the Linguist List

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Celtiberian". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- https://glottolog.org/resource/languoid/id/nucl1715

- Mallory, J. P. (1989). In Search of the Indo-Europeans. Thames & Hudson. p. 106. ISBN 0-500-05052-X.

- McCone, Kim (1996). Towards a Relative Chronology of Ancient and Medieval Celtic Sound Change. Maynooth: Dept. of Old and Middle Irish, St. Patrick's College. ISBN 0-901519-40-5.

- Koch, John (2005). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABL-CIO. pp. 1465–66. ISBN 978-1-85109-440-0. Retrieved June 10, 2011.

- Lambert, Pierre-Yves. "Francisco Villar, M.a Pilar Fernandez Álvarez, ed. Religión, lengua y cultura prerromanas de Hispania, Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca, 2001 (Acta Salmanticensia, Estudios Filológicos, 283). = Actas del VIII Coloquio internacional sobre lenguas y culturas prerromanas de la Península Ibérica (11-14 mai 1999, Salamanque)". In: Etudes Celtiques, vol. 35, 2003. p. 393. [www.persee.fr/doc/ecelt_0373-1928_2003_num_35_1_2242_t1_0386_0000_2]

- De Bernardo, P. "La gramática celtibérica del bronce de Botorrita. Nuevos Resultados". In Palaeohispanica 9 (2009), pp. 683-699.

- Schmidt, K. H. "How to define celtiberian archaims?". in Palaeohispanica 10 (2010), pp. 479-487.

- De Bernardo Stempel, Patrizia 2009 "El nombre -¿céltico?- de la Pintia vaccea". BSAA Arqueología Nº. 75, (243-256).

- Wodtko, Dagmar S. "An outline of Celtiberian grammar" 2003

- Václav, Blažek (2013-07-04). "Gaulish language". digilib.phil.muni.cz. Retrieved 2018-10-20.

- Gorrochategui, Joaquín 1991 "Descripción y posición lingiiistica del celtibérico" in "Memoriae L. Mitxelena magistri sacrum vol I (3-32)". Ed. Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea

- Beltrán Lloris, F. Jordán Cólera, C. Marco Simón, F. 2005 "Novedades epigráficas en Peñalba de Villastar (Teruel)". Palaeohispánica: Revista sobre lenguas y culturas de la Hispania antigua Nº. 5, 911-956: ENIOROSEI Dat. sg. de un tema en -i. LVGVEI, Dat. sg. de un tema en -u. ERECAIAS, Gen .sg. de un tema en -a, TIASO, Gen. sg. de un tema en -o

- Villar Liébana, F. 1996 "Fonética y Morfología Celtibéricas". La Hispania prerromana : actas del VI Coloquio sobre lenguas y culturas prerromanas de la Península Ibérica (339-378): 1) filiación expresada mediante genitivo y cuya desinencia es -as < (*-ās) y 2) origen que se expresa mediante ablativo, cuya desinencia es -az < (*-ād)

- Jordán Cólera, Carlos "La forma verbal cabint del bronce celtibérico de Novallas". En Emerita, Revista de Lingüística y Filología Clásica LXXXII 2, 2014, pp. 327-343

- Prósper, Blanca María 2006 "Soz auku arestalo tamai. La segunda línea del bronce de Botorrita y el anafórico celtibérico". Palaeohispánica: Revista sobre lenguas y culturas de la Hispania antigua, Nº. 6 (139-150).

- Prósper, Blanca M. 2002: «La gran inscripción rupestre celtibérica de Peñalba de Villastar. Una nueva interpretación», Palaeohispanica 2, pp. 213-226.

Sources

- Alberro, Manuel. The celticisation of the Iberian Peninsula, a process that could have had parallels in other European regions. In: Etudes Celtiques, vol. 35, 2003. pp. 7-24. [DOI: https://doi.org/10.3406/ecelt.2003.2149]; www.persee.fr/doc/ecelt_0373-1928_2003_num_35_1_2149

- Anderson, James M. "Preroman indo-european languages of the hispanic peninsula" . In: Revue des Études Anciennes. Tome 87, 1985, n°3-4. pp. 319-326. [DOI: https://doi.org/10.3406/rea.1985.4212]; [www.persee.fr/doc/rea_0035-2004_1985_num_87_3_4212]

- Hoz, Javier de. "Lepontic, Celtiberian, Gaulish and the archaeological evidence". In: Etudes Celtiques. vol. 29, 1992. Actes du IXe congrès international d'études celtiques. Paris, 7-12 juillet 1991. Deuxième partie : Linguistique, littératures. pp. 223-240. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3406/ecelt.1992.2006

- Hoz, Javier de. (1996). The Botorrita first text. Its epigraphical background; in: Die größeren altkeltischen Sprachdenkmäler. Akten des Kolloquiums Innsbruck 29. April - 3. Mai 1993, ed. W. Meid and P. Anreiter, 124–145, Innsbruck.

- Jordán Cólera, Carlos: (2004). Celtibérico. . University of Zaragoza, Spain.

- Joseph, Lionel S. (1982): The Treatment of *CRH- and the Origin of CaRa- in Celtic. Ériu n. 33 (31-57). Dublín. RIA.

- Lorrio, Alberto J. "Les Celtibères: archéologie et culture". In: Etudes Celtiques. vol. 33, 1997. pp. 7-36. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3406/ecelt.1997.2109

- Luján, Eugenio R. "Celtic and Celtiberian in the Iberian peninsula". In: E. Blasco et al. (eds.). Iberia e Sardegna. Le Monnier Universitá. 2013. pp. 97-112. ISBN 978-88-00-74449-2

- Luján, Eugenio R.; Lorrio, Alberto J. "Un puñal celtibérico con inscripción procedente de Almaraz (Cáceres, España)". In: Etudes Celtiques, vol. 43, 2017. pp. 113-126. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3406/ecelt.2017.1096

- McCone, Kim.(1996): Towards a relative chronology of ancient and medieval Celtic sound change Maynooth Studies in Celtic Linguistics 1. Maynooth. St. Patrick's College.

- Meid, Wolfgang. (1994). Celtiberian Inscriptions, Archaeolingua, edd. S. Bökönyi and W. Meid, Series Minor, 5, 12–13. Budapest.

- Schrijver, Peter (1991): The reflexes of the Proto-Indo-European laryngeals in Latin. Amsterdam. Ed. Rodopi.

- Schumacher, Stefan (2004): Die keltischen Primärverben: ein vergleichendes, etymologisches und morphologisches Lexikon. Innsbrucker Beiträge zur Sprachwissenschaft vol. 110. Universität Innsbruck.

- Untermann, Jürgen. (1997): Monumenta Linguarum Hispanicarum. IV Die tartessischen, keltiberischen und lusitanischen Inschriften, Wiesbaden.

- Velaza, Javier (1999): Balance actual de la onomástica personal celtibérica, Pueblos, lenguas y escrituras en la Hispania Prerromana, pp. 663–683.

- Villar, Francisco (1995): Estudios de celtibérico y de toponimia prerromana, Salamanca.

- Zair, Nicholas. (2012): The Reflexes of the Proto-Indo-European Laryngeals in Celtic. Leiden. Ed. Brill.

Further reading

- Simón Cornago, Ignacio; Jordán Cólera, Carlos Benjamín. "The Celtiberian S. A New Sign in (Paleo)Hispanic Epigraphy". In: Tyche 33 (2018). pp. 183-205. ISSN 1010-9161

External links

| For a list of words relating to Celtiberian, see the Celtiberian language category of words in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |