Transylvanian Saxons

The Transylvanian Saxons (German: Siebenbürger Sachsen; Transylvanian Saxon: Siweberjer Såksen; Romanian: Sași ardeleni, sași transilvăneni/transilvani; Hungarian: Erdélyi szászok) are a people of German ethnicity who were settled in Transylvania (German: Siebenbürgen) in waves starting from the mid 12th century until the late Modern Age (more specifically mid-19th century). The Transylvanian 'Saxons' originally stemmed from Flanders, Hainaut, Brabant, Liège, Zeeland, Moselle, Lorraine, and Luxembourg, then situated in the north-western territories of the Holy Roman Empire around the 1140s.[4]

Coat of arms of the Transylvanian Saxon University in the Middle Ages | |

| Total population | |

| c. 13,000–200,000[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

(mainly Transylvania) | c. 13,000[2][3] |

| Languages | |

| |

| Religion | |

| Lutheran majority with Reformed, Catholic, and Unitarian minorities | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Germans, Luxembourgers, Flemish people, and Walloons | |

After 1918 and the dissolution of Austria-Hungary, in the wake of the Treaty of Trianon, Transylvania was joined to the Kingdom of Romania. Consequently, the Transylvanian Saxons, together with other ethnic German sub-groups in newly enlarged Romania (namely Banat Swabians, Sathmar Swabians, Bessarabia Germans, Bukovina Germans, Dobrujan Germans, and Zipser Germans), became part of that country's broader German minority. Today, relatively few still live in Romania, where the last official census carried out in 2011 indicated 36,042 Germans, out of which 11,700 were of Transylvanian Saxon descent.[5]

Historical overview

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 211,748 | — |

| 1890 | 217,640 | +2.8% |

| 1900 | 233,019 | +7.1% |

| 1910 | 244,085 | +4.7% |

| 1941 | 241,000 | −1.3% |

| 1948 | 160,000 | −33.6% |

| 1989 | 95,000 | −40.6% |

| 2003 | 14,000 | −85.3% |

| Late 19th to early 21st century statistics of Transylvanian Saxons recorded in Transylvania and, later on, Romania as a whole. | ||

The colonization of Transylvania by Germans began under the reign of King Géza II of Hungary (1141–1162). For decades, the main task of these medieval German-speaking settlers was to defend the southeastern borders of the Kingdom of Hungary against foreign invaders stemming most notably from Central Asia (e.g. Cumans and Tatars).

The first wave of settlement continued well until the end of the 13th century. Although the colonists came mostly from the western Holy Roman Empire and generally spoke Franconian dialects, they came to be collectively referred to as 'Saxons' because of Germans working for the Hungarian chancellery. Gradually, the type of medieval German once spoken by these craftsmen, guardsmen, and workers became known locally as Såksesch.

The Transylvanian Saxon population has been steadily decreasing since World War II in native Romania. Transylvanian Saxons started massively leaving the territory of present-day Romania during and after World War II, relocating initially to Austria, then predominantly to southern Germany (especially in Bavaria).

The process of emigration continued during the Communist rule in Romania. After the collapse of the Ceaușescu regime in 1989, approximately half a million of them fled to unified Germany.[6]

Nowadays, the vast majority of Transylvanian Saxons live in either Germany or Austria. Nonetheless, a sizable Transylvanian Saxon population also resides today in North America, most notably in the United States (specifically in Idaho, Ohio, and Colorado), as well as in Canada (southern Ontario more precisely).

Origins and medieval settlements

Green = main region of origin of the initial settlers

Yellow = secondary regions of origin

The initial phase of German settlement began in the expansive mid-12th century, with colonists travelling to what would become Altland or Hermannstadt Provinz, based around the city of Hermannstadt, today's Sibiu. Although the primary reason for Géza II's invitation was border defense, similar to employing the Székelys against invaders, Germans were also sought for their mining expertise and ability to develop the region's economy. Most colonists to this area came from Luxembourg and the Moselle River region (see for instance Medardus de Nympz).

A second phase of German settlement during the early 13th century consisted of settlers primarily from the Rhineland, the southern Low Countries, and the Moselle region, with others from Thuringia, Bavaria, and even from France. A settlement in northeastern Transylvania was centered on the town of Nösen, the later Bistritz (Bistrița), located on the Bistrița River. The surrounding area became known as the Nösnerland.

Continued immigration from the Empire expanded the area of the Saxons further to the east. Settlers from the Hermannstadt region spread into the Hârtibaciu River valley (Harbachtal) and to the foot of the Cibin (German: Zibin) and Sebeș (German: Mühlbacher) mountains.

The latter region, centered around the city of Mühlbach (Sebeș), was known as Unterwald. To the north of Hermannstadt they settled what they called the Weinland including the village of Nympz (Latin for Nemșa / Nimesch) near Mediasch (Mediaș). Allegedly, the term Saxon was applied to all Germans of these historical regions because the first German settlers who came to the Kingdom of Hungary were either poor miners or groups of convicts from Saxony.[7]

In 1211 King Andrew II of Hungary invited the Teutonic Knights to settle and defend the Burzenland in the southeastern corner of Transylvania. To guard the mountain passes of the Carpathians (Karpaten) against the Cumans, the Knights constructed numerous castles and towns, including the major city of Kronstadt (Brașov). Alarmed by the Knights' rapidly expanding power, in 1225 Andrew II expelled the Order, which henceforth relocated to Prussia in 1226, although the colonists remained in Burzenland. The Kingdom of Hungary's medieval eastern borders were therefore defended in the northeast by the Nösnerland Saxons, in the east by the Hungarian border guard tribe of the Székelys, in the southeast by the castles built by the Teutonic Knights and Burzenland Saxons, and in the south by the Altland Saxons.

Medieval organization

Legal organization

Although the knights had left Transylvania, the Saxon colonists remained, and the king allowed them to retain the rights and obligations included within the Diploma Andreanum of 1224 by Andrew II of Hungary. This document conferred upon the German population of the territory between Draas (Drăușeni) and Broos (Orăștie) both administrative and religious autonomy and obligations towards the kings of Hungary. The territory that was colonized by Germans covered an area of about 30,000 km2. The region was called as Royal Lands or Saxon Lands (German: Königsboden; Hungarian: Királyföld; Romanian: Pământul crăiesc; Latin: Fundus Regius). During the reign of King Charles I of Hungary (probably 1325-1329), the Saxons were organized in the Saxon Chairs (or seats):

| Heraldry | Seat | City |

|---|---|---|

|

Repser Stuhl | Reps/Räppes (Rupea, Kőhalom) |

|

Grossschenker Stuhl | Groß-Schenk/Schoink (Cincu, Nagysink) |

|

Schässburger Stuhl | Schäßburg/Schäsbrich (Sighișoara, Segesvár) |

|

Mühlbacher Stuhl | Mühlbach/Melnbach (Sebeș, Szászsebes) |

|

Brooser Stuhl | Broos (Orăștie, Szászváros) |

|

Hermannstädter Hauptstuhl | Hermannstadt/Härmeschtat (Sibiu, Nagyszeben) |

|

Reussmarkter Stuhl | Reussmarkt/Reismuert (Miercurea Sibiului, Szerdahely) |

|

Mediascher Stuhl | Mediasch/Medwesch (Mediaș, Medgyes) |

|

Schelker Stuhl | Marktschelken (Șeica Mare, Nagyselyk) |

Religious organizations

Along with the Teutonic Order, other religious organizations important to the development of German communities were the Cistercian abbeys of Igrisch (Romanian: Igriș) in the Banat region respectively Kerz (Romanian: Cârța) in Fogarasch (Romanian: Făgăraș). The earliest religious organization of the Saxons was the Provostship of Hermannstadt (now Sibiu), founded 20 December, 1191. In its early years, it included the territories of Hermannstadt, Leschkirch (Romanian: Nocrich), and Groß-Schenk (Romanian: Cincu), the areas that were colonized the earliest by ethnic Germans in the region.

Under the influence of Johannes Honterus, the great majority of the Transylvanian Saxons embraced the new creed of Martin Luther during the Protestant Reformation (almost all became Lutheran Protestants, with very few Calvinists), while other minor segments of the Transylvanian Saxon society remained staunchly Catholic (of Latin Rite, more specifically) or were converted to Catholicism later on. Nonetheless, one of the consequences of the Reformation was the emergence of an almost perfect equivalence, in the Transylvanian context, of the terms Lutheran and Saxon, with the Lutheran Church in Transylvania being de facto a "Volkskirche", i.e. the "national church" of the Transylvanian Saxons.

.jpg)

Biertan fortified church (German: Birthälm) was the see of the Lutheran Evangelical Bishop in Transylvania between 1572 and 1867.

Biertan fortified church (German: Birthälm) was the see of the Lutheran Evangelical Bishop in Transylvania between 1572 and 1867.

Fortification of the towns

The Mongol invasion of 1241–42 devastated much of the Kingdom of Hungary. Although the Saxons did their best to resist, many settlements were destroyed. In the aftermath of the invasion, many Transylvanian towns were fortified with stone castles and an emphasis was put on developing towns economically. In the Middle Ages, about 300 villages were defended by Kirchenburgen, or fortified churches with massive walls. Though many of these fortified churches have fallen into ruin, nowadays south-eastern Transylvania region has one of the highest numbers of existing fortified churches from the 13th to 16th centuries[8] as more than 150 villages in the area count various types of fortified churches in good shape, seven of them being included in the UNESCO World Heritage under the name of Villages with fortified churches in Transylvania. The rapid expansion of cities populated by the Saxons led to Transylvania being known in German as Siebenbürgen and Septem Castra in Latin, referring to seven of the fortified towns (see Historical names of Transylvania), most likely:

- Nösen/Bistritz (Bistrița)

- Hermannstadt (Sibiu)

- Klausenburg (Cluj-Napoca)

- Kronstadt (Brașov)

- Mediasch (Mediaș)

- Mühlbach (Sebeș)

- Schässburg (Sighișoara)

Other potential candidates for this list include:

Other notable urban Saxon settlements include:

Hermannstadt (Romanian: Sibiu)

Hermannstadt (Romanian: Sibiu)- Klausenburg (Romanian: Cluj-Napoca)

_-_center.jpg) Kronstadt (Romanian: Brașov)

Kronstadt (Romanian: Brașov)- Bistritz (Romanian: Bistrița)

- Mediasch (Romanian: Mediaș)

Mühlbach (Romanian: Sebeș)

Mühlbach (Romanian: Sebeș) Schässburg (Romanian: Sighișoara)

Schässburg (Romanian: Sighișoara).jpg) Sächsisch-Regen (Romanian: Reghin)

Sächsisch-Regen (Romanian: Reghin) Broos (Romanian: Orăștie)

Broos (Romanian: Orăștie) Heltau (Romanian: Cisnădie)

Heltau (Romanian: Cisnădie) Rosenau (Romanian: Râșnov)

Rosenau (Romanian: Râșnov) Reps (Romanian: Rupea)

Reps (Romanian: Rupea)

Status of privileged class

Along with the largely Hungarian-Transylvanian nobility and the Székelys, the Transylvanian Saxons were members of the Unio Trium Nationum (or 'Union of the Three Nations'), which was a charter signed in 1438. This agreement preserved a considerable degree of political rights for the three aforementioned groups but excluded the largely Hungarian and Romanian peasantry from political life in the principality.

During the Protestant Reformation, most Transylvanian Saxons converted to Lutheranism. As the semi-independent Principality of Transylvania was one of the most religiously tolerant states in Europe at the time, the Saxons were allowed to practice their own religion (meaning that they enjoyed religious autonomy). However, the Habsburgs still promoted Roman Catholicism to the Saxons during the Counter Reformation, but the vast majority of them remained staunchly Lutheran.

Warfare between the Habsburg Monarchy and Hungary against the Ottoman Empire from the 16th–18th centuries decreased the population of Transylvanian Saxons. All throughout this period of time, the Saxons in Transylvania served as administrators and military officers. When the Principality of Transylvania came under Austrian-Habsburg control, a smaller third phase of settlement took place in order to revitalise their demographics.

This wave of settlement included exiled Protestants from Upper Austria (the Transylvanian Landlers namely), who were given land near Hermannstadt (Sibiu). The predominantly German-populated Hermannstadt was a noteworthy cultural center within Transylvania back in the day, while Kronstadt (Brașov) represented a vital political center for the Transylvanian Saxons.

Loss of elite status

Emperor Joseph II attempted to revoke the Unio Trium Nationum in the late 18th century. His actions were aimed at the political inequality within Transylvania, especially the political strength of the Saxons.

Although his actions were ultimately rescinded, many Saxons began to see themselves as being a small minority opposed by nationalist Romanians and Hungarians. Although they remained a rich and influential group, the Saxons were no longer a dominant class within Modern Age Transylvania.

The Hungarians, on the other hand, supported complete unification of Transylvania with the rest of Hungary. Stephan Ludwig Roth, a pastor who led the German support for Romanian political rights, was executed by Hungarian radicals during the revolution.

Although the Hungarian control over Transylvania was defeated by Austrian and Imperial Russian forces in 1849, the Ausgleich compromise between Austria and Hungary in 1867 did not marry well for the political rights of the Saxons. After the end of World War I, on 8 January 1919 the representatives of the Transylvanian Saxons decided to support the unification of Transylvania with the Kingdom of Romania.

They were promised full minority rights, but many wealthy Saxons lost part of their land in the land reform process that was implemented in the whole of Romania after World War I. Taking into account the rise of Adolf Hitler in Germany, many Transylvanian Saxons became staunch supporters of National Socialism, the Evangelical Lutheran Church very much losing its influence in the community.

World War II and afterwards

In February 1942, respectively in May 1943, Germany concluded agreements with Hungary, respectively with Romania, following which the Germans who were fit for military service, although Hungarian citizens (in Northern Transylvania, entered the composition of the Hungarian state through the Second Vienna Award) or Romanian citizens (in Southern Transylvania, remaining part of Romania), could be incorporated into the regular German military units, into the Waffen-SS and into war-producing enterprises or into the Organisation Todt.

As a result of these agreements, approximately 95% of the members of the German ethnic group who were fit for military service (Transylvanian Saxons and Banat Swabians) voluntarily enrolled into the Waffen-SS units (approximately 63,000 people), with several thousand serving in the special units of the SS Security Service (SD-Sonderkommandos), of which at least 2,000 ethnic Germans were enrolled in the concentration camps (KZ-Wachkompanien), of which at least 55% served in extermination camps, predominantly in Auschwitz and Lublin.[9][10][11] About 15% of the Romanian ethnic Germans who served in the Waffen-SS died in the war, with only a few thousand survivors returning to Romania.[12]

When Romania signed a peace treaty with the Soviets in 1944, the German military began withdrawing the Saxons from Transylvania; this operation was most thorough with the Saxons of the Nösnerland (Bistrița area). Around 100,000 Germans fled before the Soviet Red Army, but Romania did not conduct the expulsion of Germans as did neighboring countries at war's end. However, more than 70,000 Germans from Romania were arrested by the Soviet Army and sent to labour camps in contemporary Ukraine for alleged cooperation with Nazi Germany.

Because they are considered Auslandsdeutsche ("Germans from abroad") by the German government, the Saxons have the right to German citizenship under the law of return. Numerous Saxons have emigrated to Germany, especially after the fall of the Eastern Bloc in 1989 and are represented by the Association of Transylvanian Saxons in Germany. Due to this emigration from Romania the population of Saxons is dwindling. At the same time, especially after Romania's accession into NATO and the EU, many Transylvanian Saxons are returning from Germany, reclaiming property lost to the former Communist regime and/or starting up small and medium-sized enterprises. The Saxons remaining in Romania are represented by the Democratic Forum of Germans in Romania (FDGR/DFDR), the political party that gave Romania its fifth president, Klaus Iohannis.

Culture

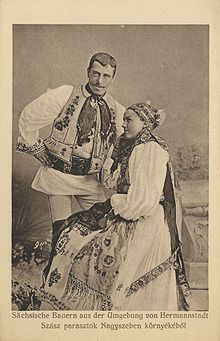

Before their expulsion from Communist Romania, the Transylvanian Saxons formed distinct communities in towns and villages, where they maintained ethnic tradition characterized by specific customs, folklore, way of life, and distinctive clothing style (i.e. national costumes). One of the traditions held was "Neighborhood" (Nachbarschaften) in which many households formed a small supporting community. This, according to some scholars, is of ancient German origin.

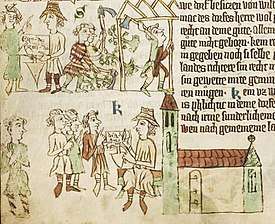

Upper part: the locator (with a special hat) receives the foundation charter from the landlord. The settlers clear the forest and build houses. Lower part: the locator acts as the judge in the village.

Upper part: the locator (with a special hat) receives the foundation charter from the landlord. The settlers clear the forest and build houses. Lower part: the locator acts as the judge in the village. National costumes of the Saxons, Germany 2015

National costumes of the Saxons, Germany 2015 The "community chest" in which the Saxon fraternity held their documents

The "community chest" in which the Saxon fraternity held their documents The "community badge" (Nachbarschaft Convener)

The "community badge" (Nachbarschaft Convener) The historical coat of arms of the Transylvanian Saxons

The historical coat of arms of the Transylvanian Saxons Alternative coat of arms of the Transylvanian Saxons

Alternative coat of arms of the Transylvanian Saxons

See also

- Germans

- Germans of Romania

- Villages with fortified churches in Transylvania

- List of fortified churches in Transylvania

- List of Transylvanian Saxon localities

- List of Transylvanian Saxons

- Transylvanian Saxon dialect

- Siebenbürgenlied

- Transylvanian Museum

- Seat (territorial administrative unit)

- The Pied Piper of Hamelin is said to have been inspired by a migration of Germans to Transylvania.[13]

- Flight and expulsion of Germans (1944–1950)

References

- The lowest figure indicates approximate contemporary distribution in Transylvania, central Romania, whereas the highest one applies worldwide.

- Nowotnick, Michaela (2016-12-30). "Herbst über Siebenbürgen". Neue Zürcher Zeitung.

- Romanian 2011 population census

- Prof. Jan de Maere: FLANDRENSES, MILITES ET HOSPITES" A HISTORY OF TRANSYLVANIA (2013) Link:

- http://www.recensamantromania.ro/rezultate-2/, table no. 8

- McGrath, Stephen (10 September 2019). "The last of Transylvania's Saxons". BBC. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- K. Gündisch, "Autonomie de stări și regionalitate în Ardealul medieval, în Transilvania și sașii ardeleni" în istoriografie, Asociația de Studii Transilvane, Sibiu, Heidelberg, 2001, pp. 33–53.

- Villages with Fortified Churches in Transylvania. UNESCO World Heritage Centre 1992–2010

- Paul Milata: Zwischen Hitler, Stalin and Antonescu. Rumäniendeutsche in der Waffen-SS, Böhlau Verlag Köln, Weimar, Wien 2007, ISBN 978-3-412-13806-6, p. 262

- Jan Erich Schulte, Michael Wildt (Hg.), Die SS nach 1945: Entschuldungsnarrative, populäre Mythen, europäische Erinnerungsdiskurse, V&R unipress, Göttingen, 2018, p.384-385

- Paul Milata, Motive rumäniendeutscher Freiwilliger zum Eintritt in die Waffen-SS in Die Waffen-SS, Neue Forschungen, Series; Krieg in der Geschichte, Volume: 74, ISBN 9783657773831, Verlag Ferdinand Schöningh, 2014, pp. 216-217

- Paul Milata: Zwischen Hitler, Stalin and Antonescu. Rumäniendeutsche in der Waffen-SS, Böhlau Verlag Köln, Weimar, Wien 2007, ISBN 978-3-412-13806-6

- Wolfgang Mieder. The Pied Piper: A Handbook. Greenwood Press, 2007. p. 67. ISBN 0-313-33464-1. Accessed via Google Books September 3, 2008.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Transylvanian Saxons. |

- Unsere Deutsche Wurzeln/Our German Roots - Namensemantik (Deutung) der Siebenbürgisch-Sächsiche Familliennamen (Surnames) (in German)

- Map and list of Transylvanian Saxon villages

- An Outline of Transsilvanian-Saxon History by Klaus Popa, MA

- The History of Transylvania and the Transylvania Saxons by Dr. Konrad Gündisch

- Transylvanian Saxon surnames

- Transylvanian placenames in different languages (in German)

- General site on the Transylvanian Saxons (in German)

- General forum for the Transylvanian Saxons (in German)

- Alliance of Transylvanian Saxons

- 'Hover & Hear' pronunciations in the Transylvanian Saxon language as spoken in Honigberg (Hărman), and compare with equivalents in English and other Germanic languages.

- Article in the academic journal Nationalities Papers on Transylvanian Saxon identity between 1933 and 1944