Euronext

Euronext N.V. (short for European New Exchange Technology[14]) is a European stock exchange with registered office in Amsterdam and corporate headquarters at La Défense in Greater Paris[15] which operates markets in Amsterdam, Brussels, London, Lisbon, Dublin, Oslo and Paris.[16] With around 1,500 listed companies worth €4.1 trillion in market capitalisation as of end July 2019, Euronext is the largest stock exchange in continental Europe. In addition to cash and derivatives markets, Euronext provides listing market data, market solutions, custody and settlement services.[17] Its total product offering includes equities, exchange-traded funds, warrants and certificates, bonds, derivatives, commodities and indices as well as a foreign exchange trading platform.

| |

| Traded as | Euronext: ENX CAC Mid 60 Component |

|---|---|

| ISIN | NL0006294274 |

| Industry | financial services |

| Founded | 22 September 2000 |

| Founder | Euronext Amsterdam, Euronext Brussels, Euronext Paris |

| Headquarters |

|

| Revenue | 458,500,000 euro (2014) |

Number of employees | 850 (31 March 2014) |

| Website | www |

Locations of Euronext stock exchanges (clockwise): London, Brussels, Lisbon, Paris, Amsterdam | |

| Type | Stock exchange |

|---|---|

| Location | La Défense, Greater Paris, France (headquarters) Amsterdam, Netherlands (registered office) |

| Founded | 1602 (Amsterdam Stock Exchange) 1724 (Paris Bourse) October 27, 2000 (present consortium[1][2][3][4]) |

| Key people | Stéphane Boujnah[5] (CEO Group and Chairman of the Managing Board) Anthony Attia[6][7] Maurice van Tilburg[8][9] Vincent Van Dessel[10] Isabel Ucha[11] (CEO Dublin) |

| Currency | Euro |

| No. of listings | 1,240 issuers (April 2018)[13] |

| Market cap | US$ 4.65 trillion (April 2018)[13] |

| Indices | Pan-European: Euronext 100 Dutch: AEX AMX (Midcap) AScX (Small Cap) Belgian: BEL20 French: CAC 40 CAC Next 20 CAC Mid 60 CAC Small SBF 250 Irish: ISEQ 20 Norwegian: OSEAX OBX Portuguese: PSI-20 |

| Website | Euronext.com |

Tracing its origins back to the founding of the Amsterdam Stock Exchange in 1602 by the Dutch East India Company and of the Paris Bourse in 1724 following the financial debacle of the Mississippi bubble, Euronext was founded in 2000 by the merger of the exchanges in Amsterdam, Paris and Brussels.[18] Euronext has since grown by developing services and acquiring additional exchanges and has, after being merged with the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) from 2007 to 2014 as NYSE Euronext, been spun off to once again being a standalone European exchange.

Since its IPO in 2014,[19] Euronext has expanded its European footprint and diversified its revenue streams by acquiring FastMatch,[20] a global FX spot market operator, in 2017, the Irish Stock Exchange in 2018[21] and Oslo Børs VPS, the owner of the Norwegian stock exchange, in 2019.[22]

History

Pre-merger exchanges

Amsterdam (1602–2000)

The Amsterdam Stock Exchange (Dutch: Amsterdamse effectenbeurs) was considered the oldest "modern" securities market in the world.[23] It was shortly after the establishment of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) in 1602 when equities began trading on a regular basis as a secondary market to trade its shares. Prior to that, the market existed primarily for the exchange of commodities.[24] In that year, the States General of the Netherlands granted the VOC a 21-year charter over all Dutch trade in Asia and quasi-governmental powers. The monopolistic terms of the charter effectively granted the VOC complete authority over trade defenses, war armaments, and political endeavors in Asia. The first multi-national corporation with significant resource interests was thereby established. In addition, the high level of risk associated with trade in Asia gave the VOC its private ownership structure. Following in the footsteps of the English East India Company, stock in the corporation was sold to a large pool of interested investors, who in turn received a guarantee of some future share of profits.[25] In the Amsterdam East India House alone, 1,143 investors subscribed for over ƒ3,679,915 or €100 million in today's money.[26]

The subscription terms of each stock purchase offered shareholders the option to transfer their shares to a third party. Quickly a secondary market arose in the East India House for resale of this stock through the official bookkeeper. After an agreement had been reached between the two parties, the shares were then transferred from seller to buyer in the "capital book".[26] The official account, held by the East India House, encouraged investors to trade and gave rise to market confidence that the shares weren't just being transferred on paper.[26] Thus, speculative trading immediately ensued and the Amsterdam securities market was born.

A big acceleration in the turnover rate came in 1623, after the 21-year liquidation period for the VOC ended. The terms of the initial charter called for a full liquidation after 21 years to distribute profits to shareholders. However, at this time neither the VOC nor its shareholders saw a slowing down of Asian trade, so the States General of the Netherlands granted the corporation a second charter in the West Indies.

This new charter gave the VOC additional years to stay in business but, in contrast to the first charter, outlined no plans for immediate liquidation, meaning that the money invested remained invested, and dividends were paid to investors to incentivize shareholding. Investors took to the secondary market of the newly constructed Amsterdam Stock Exchange to sell their shares to third parties.[27] These "fixed" capital stock transactions amassed huge turnover rates, and made the stock exchange vastly more important. Thus the modern securities market arose out of this system of stock exchange.

The voyage to the precious resources in the West Indies was risky. Threats of pirates, disease, misfortune, shipwreck, and various macroeconomic factors heightened the risk factor and thus made the trip wildly expensive. So, the stock issuance made possible the spreading of risk and dividends across a vast pool of investors. Should something go wrong on the voyage, risk was mitigated and dispersed throughout the pool and investors all suffered just a fraction of the total expense of the voyage.

The system of privatizing national expeditions was not new to Europe, but the fixed stock structure of the East India Company made it one of a kind. In the decade preceding the formation of the VOC, adventurous Dutch merchants had used a similar method of "private partnership" to finance expensive voyages to the East Indies for their personal gain.[28] The ambitious merchants pooled money together to create shipping partnerships for exploration of the East Indies. They assumed a joint-share of the necessary preparations (i.e. shipbuilding, stocking, navigation) in return for a joint-share of the profits.[28] These Voorcompagnieën took on extreme risk to reap some of the rewarding spice trade in the East Indies, but introduced a common form of the joint-stock venture into Dutch shipping.

Although some of these voyages predictably failed, the ones that were successful brought promise of wealth and an emerging new trade. Shortly after these expeditions began, in 1602, the many independent Voorcompagnieën merged to form the massive Dutch East India Trading Company.[28] Shares were allocated appropriately by the Amsterdam Stock Exchange and the joint-stock merchants became the directors of the new VOC.[28] Furthermore, this new mega-corporation was immediately recognized by the Dutch provinces to be equally important in governmental procedures. The VOC was granted significant war-time powers, the right to build forts, the right to maintain a standing army, and permission to conduct negotiations with Asian countries.[25] The charter created a Dutch colonial province in Indonesia, with a monopoly on Euro-Asian trade.

The rapid development of the Amsterdam Stock exchange in the mid 17th century lead to the formation of trading clubs around the city. Traders met frequently, often in a local coffee shop or inns to discuss financial transactions. Thus, "Sub-markets" emerged, in which traders had access to peer knowledge and a community of reputable traders.

These were particularly important during trading in the late 17th century, where short-term speculative trading dominated. The trading clubs allowed investors to attain valuable information from reputable traders about the future of the securities trade.[29] Experienced traders on the inside circle of these trading clubs had a slight advantage over everyone else, and the prevalence of these clubs played a major role in the continued growth of the stock exchange itself.

Additionally, similarities can be drawn between modern day brokers and the experienced traders of the trading clubs. The network of traders allowed for organized movement of knowledge and quick execution of transactions. Thus, the secondary market for VOC shares became extremely efficient, and trading clubs played no small part. Brokers took a small fee in exchange for a guarantee that the paperwork would be appropriately filed and a "buyer" or "seller" would be found. Throughout the 17th century, investors increasingly sought experienced brokers to seek information about a potential counterparty.[30]

The European Options Exchange (EOE) was founded in 1978 in Amsterdam as a futures and options exchange. In 1983 it started a stock market index, called the EOE index, consisting of the 25 largest companies that trade on the stock exchange. Forward contracts, options, and other sophisticated instruments were traded on the Amsterdam Stock Exchange well before this.[24]

In 1997 the Amsterdam Stock Exchange and the EOE merged, and its blue chip index was renamed AEX, for "Amsterdam EXchange". It is now managed by Euronext Amsterdam. On 3 October 2011, Princess Máxima opened the new trading floor of the Amsterdam Stock Exchange.[31]

The former Stock Exchange building was the Beurs van Berlage.

Although it is usually considered to be the first stock market, Fernand Braudel argues that this is not precisely true:

"It is not quite accurate to call [Amsterdam] the first stock market, as people often do. State loan stocks had been negotiable at a very early date in Venice, in Florence before 1328, and in Genoa, where there was an active market in the luoghi and paghe of Casa di San Giorgio, not to mention the Kuxen shares in the German mines which were quoted as early as the fifteenth century at the Leipzig fairs, the Spanish juros, the French rentes sur l’Hotel de Ville (municipal stocks) (1522) or the stock market in the Hanseatic towns from the fifteenth century. The statutes of Verona in 1318 confirm the existence of the settlement or forward market ... In 1428, the jurist Bartolomeo de Bosco protested against the sale of forward loca in Genoa. All evidence points to the Mediterranean as the cradle of the stock market. But what was new in Amsterdam was the volume, the fluidity of the market and publicity it received, and the speculative freedom of transactions."

— Fernand Braudel (1983)[23]

However, it is the first incarnation of what we could today recognize as a stock market.

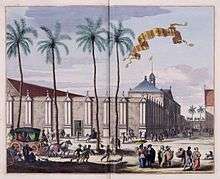

The Amsterdam Bourse, an open-air venue, was created as a commodity exchange in 1530 and rebuilt in 1608.[32] Rather than being a bazaar where goods were traded intermittently, exchanges had the advantage of being a regularly meeting market, which enabled traders to become more specialized and engage in more complicated transactions.[23][24] As early as the middle of the sixteenth century, people in Amsterdam speculated in grain and, somewhat later, in herring, spices, whale-oil, and even tulips. The Amsterdam Bourse in particular was the place where this kind of business was carried on. This institution as an open-air market in Warmoestreet, later moved for a while to the ‘New Bridge,’ which crosses the Damrak, then flourished in the ‘church square’ near the Oude Kerk until the Amsterdam merchants built their own exchange building in 1611.[33] Transactions had to be logged into the official accounts book in the East India house, indeed trading was highly sophisticated.[24] Early trading in Amsterdam in the early 16th century (1560s–1611) largely occurred by the Nieuwe Brug bridge, near Amsterdam Harbor.[34][35] Its proximity to the harbor and incoming mail made it a sensible location for traders to be the first to get the latest commercial news.[36]

Shortly thereafter, the city of Amsterdam ordered the construction of an exchange in Dam Square. It opened in 1611 for business, and various sections of the building were marked for commodity trading and VOC securities.[37] A bye-law on trade in the city dictated that trade could only take place in the exchange on weekdays from 11 a.m. to noon.[38] While only a short amount of time for trading inside the building, the window created a flurry of investors that in turn made it easier for buyers to find sellers and vice versa. Thus, the building of the stock exchange led to a vast expansion of liquidity in the marketplace. In addition, trading was continued in other buildings, outside of the trading hours of the exchange, such as the trading clubs, and was not prohibited in hours outside of those outlined in the bye-law.[38]

The location of exchange relative to the East India house was also strategic. Its proximity gave investors the luxury of walking a short distance to both register the transaction in the official books of the VOC, and complete the money transfer in the nearby Exchange Bank, also in Dam square.[38]

Brussels (1801–2000)

The Brussels Stock Exchange (French: Bourse de Bruxelles, Dutch: Beurs van Brussel) was founded in 1801 by decree of Napoleon. As part of the covering of the river Senne for health and aesthetic reasons in the 1860s and 1870s, a massive programme of beautification of the city centre was undertaken. Architect Léon-Pierre Suys, as part of his proposal for covering of the Senne, designed a building to become the centre of the rapidly expanding business sector. It was to be located on the former butter market, (itself situated on the ruins of the former Recollets Franciscan convent) on the newly created Anspach Boulevard (then called 'Central Boulevard'). The building was erected from 1868 to 1873, and housed the Brussels Stock Exchange until 1996. The Bourse is due to become a beer museum and will open to the public in 2018.[39] The building does not have a distinct name, though it is usually called simply the Bourse/Beurs. It is located on Boulevard Anspach, and is the namesake of the Place de la Bourse/Beursplein, which is, after the Grand Place, the second most important square in Brussels. The building combines elements of the Neo-Renaissance and Second Empire architectural styles. It has an abundance of ornaments and sculptures, created by famous artists, including the brothers Jacques and Joseph Jacquet, Guillaume de Groot, French sculptor Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse and his then-assistant Auguste Rodin.

Paris (1724–2000)

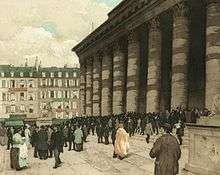

The Paris Stock Exchange (French: Bourse de Paris) was located in Palais Brongniart in the Place de la Bourse, in the II arrondissement, Paris. Historically, stock trading took place at several spots in Paris, including rue Quincampoix, rue Vivienne (near the Palais Royal), and the back of the Opéra Garnier (the Paris opera house).

In the early 19th century, the Paris Bourse's activities found a stable location at the Palais Brongniart, or Palais de la Bourse, built to the designs of architect Alexandre-Théodore Brongniart from 1808 to 1813 and completed by Éloi Labarre from 1813 to 1826.[40]

Brongniart had spontaneously submitted his project, which was a rectangular neoclassical Roman temple with a giant Corinthian colonnade enclosing a vaulted and arcaded central chamber. His designs were greatly admired by Napoleon and won Brongniart a major public commission at the end of his career. Initially praised, the building was later attacked for academic dullness. The authorities had required Brongniart to modify his designs, and after Brongniart's death in 1813, Labarre altered them even further, greatly weakening Brongniart's original intentions. From 1901 to 1905 Jean-Baptiste-Frederic Cavel designed the addition of two lateral wings, resulting in a cruciform plan with innumerable columns. According to the architectural historian Andrew Ayers, these alterations "did nothing to improve the reputation of this uninspiring monument."[40]

From the second half of the 19th century, official stock markets in Paris were operated by the Compagnie des agents de change, directed by the elected members of a stockbrokers' syndical council. The number of dealers in each of the different trading areas of the Bourse was limited. There were around 60 agents de change (the official stockbrokers). An agent de change had to be a French citizen, be nominated by a former agent or his estate, and be approved by the Minister of Finance, and he was appointed by decree of the President of the Republic. Officially, the agents de change could not trade for their own account nor even be a counterpart to someone who wanted to buy or sell securities with their aid; they were strictly brokers, that is, intermediaries. In the financial literature, the Paris Bourse is hence referred to as order-driven market, as opposed to quote-driven markets or dealer markets, where price-setting is handled by a dealer or market-maker. In Paris, only agents de change could receive a commission, at a rate fixed by law, for acting as an intermediary. However, parallel arrangements were usual in order to favor some clients' quote. The Commodities Exchange was housed in the same building until 1889, when it moved to the present Bourse de commerce.[41] Moreover, until about the middle of the 20th century, a parallel market known as "La Coulisse" was in operation.[42]

Until the late 1980s, the market operated as an open outcry exchange, with the agents de change meeting on the exchange floor of the Palais Brongniart. In 1986, the Paris Bourse started to implement an electronic trading system. This was known generically as CATS (Computer Assisted Trading System), but the Paris version was called CAC (Cotation Assistée en Continu). By 1989, quotations were fully automated. The Palais Brongniart hosted the French financial derivatives exchanges MATIF and MONEP, until they were fully automated in 1998.

Lisbon (1769–2002)

The predecessor of the Lisbon Stock Exchange (Portuguese: Bolsa de Valores de Lisboa) was created in 1769 as the Assembleia dos Homens de Negócio (Assembly of Businessmen) in the Commerce Square, in downtown Lisbon. In 1891, the Bolsa de Valores do Porto (Oporto Stock Exchange) in Oporto was founded.

After the military coup on April 25, 1974, both the Lisbon and Porto stock exchanges were closed by the revolutionary National Salvation Junta (they would be reopened a couple of years later).[43]

At the end of 2001, 65 companies were listed on BVLP-regulated markets, representing a market capitalization of Euro 96.1 billion. From January to December 2001, a total of 4.7 million futures and options contracts were traded on the BVLP market.

The Euronext Lisbon was formed in 2002 when the shares of Bolsa de Valores de Lisboa e Porto (BVLP) were acquired by Euronext and the exchange was merged into the pan-European exchange. BVLP, the Portuguese exchange, was formed in the 1990s restructuring of the Lisbon Stock Exchange association and the Porto Derivatives Exchange Association.

Dublin (1799–2018)

_p083_THE_ROYAL_EXCHANGE.jpg)

The Irish Stock Exchange (ISE; Irish: Stocmhalartán na hÉireann) was first recognised by legislation in 1799 when the Irish Parliament passed the Stock Exchange (Dublin) Act.[3] In different periods in its history, the ISE included a number of regional exchanges, including the Cork and Dublin exchanges. The first woman to be admitted to a stock exchange was, Oonah Keogh to the Dublin Stock Exchange in 1925. In 1973, the Irish exchange merged with British and other Irish stock exchanges becoming part of the International Stock Exchange of Great Britain and Ireland (now called the London Stock Exchange).

In 1995, it became independent again and in April 2014 it demutualised changing its corporate structure and becoming a plc which is owned by a number of stockbroking firms.

At the time of its demutualisation the country's main stockbrokers received shares in the €56m-valued exchange and dividing up €26m in excess cash. Davy Stockbrokers took the largest stake, at 37.5 per cent, followed by Goodbody Stockbrokers with 26.2 per cent; Investec with 18 per cent; the then Royal Bank of Scotland Group 6.3 per cent; Cantor Fizgerald 6 per cent; and Campbell O’Connor with 6 per cent.

In March 2018, Euronext completed the purchase of the ISE, and renamed the ISE as Euronext Dublin.[44]

Oslo (1818–2019)

Oslo Børs was established by a law of September 18, 1818. Trading on Oslo Børs commenced on April 15, 1819. In 1881 Oslo Børs became a stock exchange, which means securities were listed. The first listing of securities contained 16 bond series and 23 stocks, including the Norwegian central bank (Norges Bank). Oslo Børs cooperates with London Stock Exchange on trading systems. The exchange has also a partnership with the stock exchanges in Singapore and Toronto (Canada) for a secondary listing of companies. The stock exchange was privatized in 2001, and is, after the merger in 2007, 100% owned by Oslo Børs VPS Holding ASA.

The over 180-year-old stock exchange building has been the subject of many long debates about how the building should be managed and designed over the years. Several of Christiania's (the name of Oslo between 1624 and 1925) best known business men fought for years to get approved and funded the construction of a stock exchange in Christiania, the capital of Norway from 1814.

In 1823 a building committee was appointed to consider the various suggested drawings at the time. The committee chose the architect Christian H. Grosch's proposal. On July 14, 1826 the Ministry approved the final plans of drawings and budgets. In 1828 it was called Norway's first monumental building, completed on the site called Grønningen, the first public park in Christiania.

2000–2007: Euronext established

Euronext was formed on 22 September 2000 following a merger of the Amsterdam Stock Exchange,[45] Brussels Stock Exchange, and Paris Bourse, in order to take advantage of the harmonization of the financial markets of the European Union.[1][2][3][4] In December 2001, Euronext acquired the shares of the London International Financial Futures and Options Exchange (LIFFE), forming Euronext.LIFFE. In 2002 the group merged with the Portuguese stock exchange Bolsa de Valores de Lisboa e Porto (BVLP), renamed Euronext Lisbon.[3] In 2001, Euronext became a listed company itself after completing its Initial Public Offering.[46][47] Euronext acquired FastMatch, a currency trading platform, in 2017[48] and the Irish Stock Exchange in March 2018 to further expand its pan-European model.[49]

2007–2014: Merger with the New York Stock Exchange

Euronext merged with NYSE Group, Inc. on April 4, 2007 to form NYSE Euronext (NYX). On November 13, 2013 Intercontinental Exchange (NYSE: ICE), completed acquisition of NYSE Euronext.

Due to apparent moves by NASDAQ to acquire the London Stock Exchange,[50] NYSE Group, owner of the New York Stock Exchange, offered €8 billion (US$10.2b) in cash and shares for Euronext on 22 May 2006, outbidding a rival offer for the European Stock exchange operator from Deutsche Börse, the German stock market.[51] Contrary to statements that it would not raise its bid, on 23 May 2006, Deutsche Börse unveiled a merger bid for Euronext, valuing the pan-European exchange at €8.6 billion (US$11b), €600 million over NYSE Group's initial bid.[52] Despite this, NYSE Group and Euronext penned a merger agreement, subject to shareholder vote and regulatory approval. The initial regulatory response by SEC chief Christopher Cox (who was coordinating heavily with European counterparts) was positive, with an expected approval by the end of 2007.[53] The new firm, tentatively dubbed NYSE Euronext, would be headquartered in New York City, with European operations and its trading platform run out of Paris. Then-NYSE CEO John Thain, who was to head NYSE Euronext, intended to use the combination to form the world's first global stock market, with continuous trading of stocks and derivatives over a 21-hour time span. In addition, the two exchanges hoped to add Borsa Italiana (the Milan stock exchange) into the grouping.

Deutsche Börse dropped out of the bidding for Euronext on 15 November 2006, removing the last major hurdle for the NYSE Euronext transaction. A run-up of NYSE Group's stock price in late 2006 made the offering far more attractive to Euronext's shareholders.[54] On 19 December 2006, Euronext shareholders approved the transaction with 98.2% of the vote. Only 1.8% voted in favour of the Deutsche Börse offer. Jean-François Théodore, the chief executive officer of Euronext, stated that they expected the transaction to close within three or four months.[55] Some of the regulatory agencies with jurisdiction over the merger had already given approval. NYSE Group shareholders gave their approval on 20 December 2006.[56] The merger was completed on 4 April 2007, forming NYSE Euronext.

In 2008 and 2009 Deutsche Börse made two unsuccessful attempts to merge with NYSE Euronext. Both attempts did not enter into advanced steps of merger.[57][58]

In 2011, Deutsche Börse and NYSE Euronext confirmed that they were in advanced merger talks. Such a merger would create the largest exchange in history.[59] The deal was approved by shareholders of NYSE Euronext on July 7, 2011,[53] and Deutsche Börse on July 15, 2011[60] and won the antitrust approved by the US regulators on December 22, 2011.[61] On February 1, 2012, the deal was blocked by European Commission on the grounds that the new company would have resulted in a quasi-monopoly in the area of European financial derivatives traded globally on exchanges.[62][63] Deutsche Börse unsuccessfully appealed this decision.[64][65]

In 2012, Euronext announced the creation of Euronext London to offer listing facilities in the UK. As such, Euronext received in June, 2014 Recognized Investment Exchange (RIE) status from Britain's Financial Conduct Authority.[66]

2012–2014: Acquisition by Intercontinental Exchange

In December 2012 Intercontinental Exchange announced plans to acquire NYSE Euronext, owner of Euronext, in an $8.2 billion takeover. [67] The deal was approved by the shareholders of NYSE Euronext and Intercontinental Exchange on June 3, 2013.[68][69][70] The European Commission approved the acquisition on 24 June 2013 [71] and on Aug. 15, 2013 the US regulator, SEC, granted approval of the acquisition. [72][73][74] European regulators and ministries of Finance of the participating countries approved the deal and on November 13, 2013 the acquisition was completed.[75][76] The fact that ICE intends to pursue an initial public offering of Euronext in 2014[75] was always part of the deal and a positive elements for European stakeholders. After a complex series of operation within a very limited frame, Euronext became public in June 2014.

2014–present: Re-emergence as a standalone exchange

On June 20, 2014 Euronext was split from ICE through an initial public offering.[77] In order to stabilize Euronext, a consortium of eleven investors decided to invest in the company. These investors referred to as "reference shareholders" own 33.36% of Euronext's capital and have a 3 years lockup period: Euroclear, BNP Paribas, BNP Paribas Fortis, Société Générale, Caisse des Dépôts, BPI France, ABN Amro, ASR, Banco Espirito Santo, Banco BPI and Belgian holding public company Belgian Federal Holding and Investment Company (SFPI/FPIM).[78] They have 3 board seats.

Alternext is a market segment formed in 2005 by Euronext to help small and mid-class companies in the Eurozone that seek financing. This initiative was later followed by the creation of EnterNext, a subsidiary of Euronext dedicated to promoting and growing the market for SMEs.[79] In May 2017, Alternext was rebranded to Euronext Growth.[80]

Enternext was created in 2013 in order to help SMEs outline and apply a strategy most suited to support their growth. Enternext is a pan-European program and comprises over 750 SMEs, which are listed on Euronext markets in Europe.[81] Thus, EnterNext plays a key role in Euronext's strategy to become a leading capital raising center in Europe.

In June 2014, EnterNext launched two initiatives to boost SME equity research and support the technology sector. EnterNext partnered with Morningstar to increase equity research focusing on mid-size companies, especially in the telecommunications, media and technology (TMT) sector.

On 18 June 2019, Euronext announced the completion of its acquisition of the Oslo Stock Exchange.[82]

Markets

Overview

Euronext combines five national markets in Europe, trading stocks of major companies of each country participant, and manages the main national indices representing these stocks: AEX-index, BEL 20, CAC 40 and PSI 20. Blue chip traded on Euronext represent 20+ issuers included in the EURO STOXX 50® benchmark.[83] In 2012, Euronext announced it was opening a listings venue in London under Euronext London, which strengthened the competitive position of Euronext in Europe and increased its visibility.[84][85]

| Market / Segment Name | Equities[86] | Bonds[87] | ETFs[88] | Funds[89] | ETVs / ETNs[90] | Warrants, Certificates & Structured Notes[91] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alternext Amsterdam | Yes | – | – | – | – | – |

| Alternext Brussels | Yes | Yes | – | – | – | – |

| Alternext Lisbon | Yes | – | – | – | – | – |

| Alternext Paris | Yes | Yes | – | – | – | – |

| Easynext Lisbon | Yes | – | – | – | – | Yes |

| Euronext Amsterdam | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Euronext Brussels | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Euronext Dublin | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Euronext Lisbon | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | – |

| Euronext London | Yes | – | – | – | – | – |

| Euronext Paris | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | Yes | Yes |

| Marche Libre Brussels | Yes | Yes | – | – | – | – |

| Marche Libre Paris | Yes | Yes | – | – | – | Yes |

| NYSE Bondmatch | – | Yes | – | – | – | – |

| Traded But Not Listed Amsterdam | Yes | – | – | – | – | – |

| Trading Facility Brussels | Yes | – | – | – | – | – |

Derivative market

Euronext has a leading milling wheat contract which is a benchmark for wheat prices in Europe. In June 2014, Euronext signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the Dalian Commodity Exchange (DCE).[92] This agreement aims at researching the demand for commodity products in new geographic areas and developing strategies for the distribution and trading of these products in safe and orderly markets.

| Futures/Options | Amsterdam, Netherlands | Brussels, Belgium | Lisbon, Portugal | Paris, France | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commodity | Futures | Yes | – | – | Yes |

| Commodity | Options | – | – | – | Yes |

| Index | Futures | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Index | Options | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| Stock | Futures | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Stock | Options | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| ETF | Options | Yes | – | – | – |

| Currency | Futures | Yes | – | – | – |

| Currency | Options | Yes | - | – | – |

| Dividend | Futures | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Amsterdam

Brussels

The main index of the exchange is the BEL20.

Dublin

Euronext Dublin lists debt and fund securities and has 35,000 securities listed on its markets. The exchange is used by over 4,000 issuers from more than 85 countries to raise funds and access international investors.[94] A study by Indecon (international economic consultants) published in 2014 on the Irish Stock Exchange found that having a local stock market and securities industry directly supports 2,100 jobs in Ireland and is worth €207 million each year to the Irish economy. It also found that having a domestic securities industry centered on the Irish Stock Exchange generates €207m in estimated direct economic impact (measured in Gross Value Added or GDP) and €230m in direct tax for the Irish exchequer (including stamp duty on trading in Irish shares).[95] The exchange is regulated by the Central Bank of Ireland under the Markets in Financial Instruments Regulations (MiFID) and is a member of the World Federation of Exchanges and the Federation of European Stock Exchanges.

Euronext Dublin operates 4 markets – the Main Securities Market, the principal market for Irish and overseas companies; the Enterprise Securities Market (ESM), an equity market designed for growth companies; the Global Exchange Market (GEM), a specialist debt market for professional investors and the Atlantic Securities Market (ASM), a market dedicated to companies who wish to dual list in Ireland and the United States.[96]

There are currently 50 companies with shares listed on the markets of the Irish Stock Exchange.[97]

There are three markets on which for companies to list equities on the ISE:

- The Main Securities Market (MSM), suited to larger companies with substantial funding needs

- The Enterprise Securities Market (ESM), for high-growth companies raising equity in earlier stages of development

- The Atlantic Securities Market (ASM), for multinational companies that want to broaden their investor reach to include dollar and euro pools of capital in a streamlined manner

The ISE offers domestic and international membership for trading in shares, ETFs, Irish Government bonds and other securities.

The ISE's electronic trading platform is called ISE Xetra and is provided in partnership with Deutsche Börse since the ISE closed its trading floor in Anglesea Street (a listed building) Dublin 2 on 6 June 2000. Shares trading on the ISE are settled by Euroclear UK & Ireland via the CREST system and cleared by Eurex Clearing AG.

The ISE is the main centre of liquidity in Irish shares. The company with the highest turnover on the ISE in 2016 was CRH. This was followed Ryanair, Paddy Power Betfair, Bank of Ireland and Kerry Group.

Trading volumes on the exchange in 2011 were about a quarter of the 2007 peak. In June 2012, following the collapse of a stockbrokers, the Sunday Independent asked "Will there even be a stand-alone Irish equity market in five years' time? The omens are not good."[98] However this has proven not to be the case as in 2016 the number of equity trades had increased by 17.4% to 6.6m, up from 5.6m in 2015, the first time trading has reached over 6m trades and the sixth consecutive year of growth in trade numbers.

The ISE is among the leading centres globally for the listing of debt securities with statistics showing debt listings growing by more than 7% in 2016 to reach over 29,000 securities. The ISE was ranked at #2 among global exchanges according to rankings released by the World Federation of Exchanges (WFE) at the end of December 2016.[99]

The ISE offers two markets for the listing of debt securities: the Global Exchange Market (GEM), an exchange-regulated market and multilateral trading facility (MTF), for banks, companies and sovereigns listing debt, and the Main Securities Market (MSM). Major global companies listing debt on ISE's markets include Vodafone plc, Whirlpool, Canada Pension Plan Investment Board, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, Ryanair, Coca-Cola and Ferrari.

Lisbon

Euronext Lisbon trades equities, public and private bonds, participation bonds, warrants, corporate warrants, investment trust units, and exchange traded funds. The BVL General index is the exchanges official index, and includes all listed shares on the official market. Settlement is T+2. Derivatives include long-term interest rate futures, three-month Lisbor futures, stock index futures and options on the PSI-20 Stock index, and Portuguese stock futures. Trading hours are 8 a.m. to 4:30 p.m., Monday through Friday.

Oslo

The Oslo Stock Exchange (Norwegian: Oslo Børs) (OSE: OSLO) offers Norway's only regulated markets for securities trading today. The stock exchange offers a full product range including equities, derivatives and fixed income instruments. Oslo Børs is today an online market place where all trading is done through computer networks. Trading starts at 09:00am and ends at 04:30pm local time (CET) on all days of the week except weekends and holidays declared by Oslo Børs in advance. Oslo Børs can offer a unique international position related to the industries of energy, shipping and seafood.

There are three markets for listing and trading on the stock exchange: Oslo Børs is the largest market place for listing and trading in equities, equity certificates, ETPs (exchange traded funds and notes), derivatives and fixed income products. Established in 1819, first as an commodity exchange. Equities and bonds listed and traded from 1881.

Oslo Axess was established in May 2007 as an alternative to Oslo Børs for listing and trading in shares.

Nordic ABM was established in June 2005 as an alternative bond market.

Norwegian public limited companies and equivalent foreign companies can apply for their shares to be listed on Oslo Børs or Oslo Axess. It is up to the company itself to apply to be admitted to trading, but the company must meet the applicable requirements, which include the number of owners (range), number of shares, market value and history. To be listed the exchange includes strict requirements on the treatment of confidential information. Companies that meet the requirements for listing can much easier get access to capital through share issues. Many investors only invest in securities listed on a stock exchange, because those papers are easier to sell.

Indices: OBX – The index comprises the 25 most traded shares listed on Oslo Børs. The OBX index is tradable, meaning that you can buy and sell listed futures and options on the index. Put another way, you can get the same exposure by purchasing an index product as if you buy all the shares (weighted) included in the index. The rating is based on a six-month trading period. The index is adjusted every third Friday in June and December. OSEBX – The Oslo Børs Benchmark Index is an investable index containing a representative selection of all listed shares on Oslo Børs. The OSEBX is revised on a half year basis and the changes are implemented on December 1 and June 1.

Paris

Euronext Paris is France's securities market, formerly known as the Paris Bourse. It operates the MATIF futures exchange, which trades futures and options on interest rate products and commodities, and MONEP, equity and index futures and options. All products are traded electronically on the NSC system adopted by all of the Euronext members. Transactions are cleared through LCH.Clearnet. Cash settlement is T+2.[100] Trading hours are 9 am to 5:30 pm CET, Monday to Friday.

The French equities market is divided into three sections. The Premier Marché, formerly called the Official List, includes large French and foreign companies, and most Bond issues. The Second Marché, lists medium-sized companies, while nouveau marché lists fast-growing start up companies seeking capital to finance expansion, linked to Euro.nm, the European equity growth market. A fourth market, Marché Libre, is nonregulated, administered by Euronext Paris for transactions in securities not listed on the other three markets.

Euronext Paris calculates a family of indices. The CAC 40 is the exchange's benchmark, disseminated in real time. Its components are included in the broader SBF 120 Index, a benchmark for investment funds. The SBF 250 index, a benchmark for the long-term performance of equity portfolios, includes all of the SBF 120; it is structured by sector. The MIDCAC index includes 100 of the most liquid medium-size stocks on the Premier Marché and Nouveau Marché calculated on the basis of opening and closing prices, while the Second Marché index focuses on that market. Both indices are benchmarks for funds. The Nouveau Marché Index represents stocks in the growth market. The SBF-FCI index is based on a selection of convertible bonds that represent at least 70% of the total capitalization of this market, calculated twice daily. For derivatives, MONEP trades short-term and long-term stock options and futures and options on a family of Dow Jones indices. MATIF's products include commodity future and options on European rapeseed and futures on rapeseed meal, European rapeseed oil, milling wheat, corn and sunflower seeds; interest rate futures and options on the Euro notional bond, five-year Euro and three-month PIBOR (Paris Interbank Offered Rate), and futures on the 30-year Eurobond and two-year E-note, and index futures on the CAC 40.

For the fiscal year ending December 2004, Euronext Paris recorded sales of US$522 million, a −12.9% decrease in sales from 2003. Euronext Paris has a US$2.9 trillion total market capitalization of listed companies and average daily trading value of its combined markets of approximately US$102 billion/€77 billion (as of 28 February 2007).

Structure and indices

Euronext comprises cash and derivatives markets, which, as of December 2013, cover the following operational markets and segments.[101]

| Market / Segment Name | Cash / Derivatives | Country | City | MIC Code | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Euronext Amsterdam | Cash | Netherlands | Amsterdam | XAMS | |

| Alternext Amsterdam | Cash | Netherlands | Amsterdam | ALXA | |

| Traded But Not Listed Amsterdam | Cash | Netherlands | Amsterdam | TNLA | |

| Euronext EQF, Equities And Indices Derivatives | Derivatives | Netherlands | Amsterdam | XEUE | |

| Euronext IRF, Interest Rate Future And Options | Derivatives | Netherlands | Amsterdam | XEUI | |

| Euronext Brussels | Cash | Belgium | Brussels | XBRU | |

| Alternext Brussels | Cash | Belgium | Brussels | ALXB | |

| Easy Next | Cash | Belgium | Brussels | ENXB | MTF for Warrants and Certificates |

| Marche Libre Brussels | Cash | Belgium | Brussels | MLXB | |

| Trading Facility Brussels | Cash | Belgium | Brussels | TNLB | |

| Ventes Publiques Brussels | Cash | Belgium | Brussels | VPXB | |

| Euronext Brussels – Derivatives | Derivatives | Belgium | Brussels | XBRD | |

| Euronext Lisbon | Cash | Portugal | Lisbon | XLIS | |

| Alternext Lisbon | Cash | Portugal | Lisbon | ALXL | Alternext is the name of a market (MTF) organised in Portugal by Euronext Lisbon, Sociedade Gestora De Mercados Regulamentados, S.A. |

| Easynext Lisbon | Cash | Portugal | Lisbon | ENXL | |

| Mercado De Futuros E Opções | Derivatives | Portugal | Lisbon | MFOX | |

| Market Without Quotations Lisbon | Derivatives | Portugal | Lisbon | WQXL | |

| Euronext London | Cash | United Kingdom | London | XLDN | A UK regulated market aimed at international issuers complementary to the existing euronext Cash markets |

| Euronext Paris | Cash | France | Paris | XPAR | |

| Alternext Paris | Cash | France | Paris | ALXP | |

| NYSE Bondmatch | Cash | France | Paris | MTCH | Financial, corporate and covered bonds trading platform for professional investors. |

| Euronext Paris Matif | Derivatives | France | Paris | XMAT | |

| Marche Libre Paris | Cash | France | Paris | XMLI | |

| Euronext Paris Monep | Derivatives | France | Paris | XMON |

Indices

Euronext manages various country (national), as well as pan-European regional and sector and strategy indices.[102]

| Name | Symbol | Trading Currency |

|---|---|---|

| AEX All-share | AAX | EUR |

| AEX | AEX | EUR |

| Alternext All-share | ALASI | EUR |

| AMX | AMX | EUR |

| AScX | ASCX | EUR |

| BEL 20 | BEL20 | EUR |

| BEL All-share | BELAS | EUR |

| BEL CONTIN STCK NR | BELCU | EUR |

| BEL Mid | BELM | EUR |

| BEL Small | BELS | EUR |

| CAC 40 | PX1 | EUR |

| CAC All-share | PAX | EUR |

| CAC All-tradable | CACT | EUR |

| CAC Mid & small | CACMS | EUR |

| CAC Mid 60 | CACMD | EUR |

| CAC Next 20 | CN20 | EUR |

| CAC Small | CACS | EUR |

| Euronext 100 | N100 | EUR |

| EURONEXT FAS IAS | FIAS | EUR |

| NYSE Euronext Iberian | NEIBI | EUR |

| IEIF SIIC FRANCE | SIIC | EUR |

| Low Carbon 100 Europe | LC100 | EUR |

| Next 150 | N150 | EUR |

| Next Biotech | BIOTK | EUR |

| OSEO INNOVATION | NAOII | EUR |

| Private Equity Nxt | PENXT | EUR |

| PSI 20 | PSI20 | EUR |

| PSI All-share | BVLGR | EUR |

| REIT EUROPE | REITE | EUR |

| SBF – 120 | FCI | EUR |

Agreements and cooperation with partners

On September 22, 2014, Euronext announced its new partnership with DEGIRO[103] regarding the distribution of retail services of Euronext. Upon publishing the third quarter results for 2014, the partnership was seen as a plan for Euronext to compete more effectively on the Dutch retail segment.[104] They are still partners as of April 1, 2016.

Market data

Euronext's market data offerings cover markets in Paris, Amsterdam, Lisbon, London and Brussels and include Cash Markets Real-Time Data, Derivatives Real-Time Data, Index and End of Day Data, Reference Data and Historical Data.[105] Euronext also provides an Equity and Index Volatility Data Service that covers indices worldwide.[106] Investors, traders and professionals can also acquire market data from the Eurex Exchange through data providers like Quandl.[107]

Exchange members

As of March 30, 2016, Euronext has 259 members. 208 of these are trading members and the rest are trading clearance members. These members are also divided in brokers, dealers and fund agents. Not every member is authorized in every of the five countries available by Euronext.[108]

See also

- Bourse of Antwerp, the world's first financial exchange

- Economy of the European Union

- Euroclear

- Nord Pool, the pan-European energy exchange

- List of European stock exchanges

- List of stock exchanges

References

- Kingdom of the Netherlands-Netherlands: Detailed Assessment of Standards and Codes (Report). Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund. 2004-09-29. p. 136. IFM Country Report No 04/310. Retrieved 2013-12-27.

- Yutaka, Kurihara; Sadayoshi, Takaya; Nobuyoshi, Yamori (2006). Global Information Technology and Competitive Financial Alliances. Idea Group Inc. (IGI). p. 137. ISBN 9781591408833.

- Fabozzi, Frank J., ed. (2008). "Handbook of Finance, Financial Markets and Instruments". Handbook of Finance. 1. John Wiley & Sons. p. 143. ISBN 9780470391075. Retrieved 2013-12-27.

- Théodore, Jean-François (2000-09-22). "Birth of Euronext: Speech from Jean-François Théodore, Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of Euronext". Paris Europlace. Retrieved 2013-12-27.

- "Euronext nominates Santander's Boujnah as new CEO". Financial Times. 2015-09-10. Retrieved 2017-07-07.

- Alcaraz, Marina (2013-12-06). "Anthony Attia prend la tête d'Euronext en France". Les Échos (in French). Paris. Retrieved 2013-12-26.

- "Anthony Attia prend la tête d'Euronext France". Le Figaro (in French). Paris. 2013-12-06. Retrieved 2013-12-27.

- "Euronext appoints Maurice van Tilburg CEO". Finextra. 2015-02-02. Retrieved 2015-02-27.

- "Euronext appoints Maurice van Tilburg as CEO of Euronext Amsterdam" (Press release). Euronext. 2015-02-26. Retrieved 2015-02-02.

- "NYSE Euronext launches EnterNext® in Brussels" (Press release). NYSE Euronext. 2013-07-04. Archived from the original on 2013-12-28. Retrieved 2013-12-26.

- "Euronext appoints Isabel Ucha as CEO of Euronext Lisbon and CEO of Interbolsa" (Press release). Euronext. 2018-11-27. Retrieved 2019-08-23.

- "New CEO at Euronext Dublin". NYSE. 2014.

- "Monthly Reports – World Federation of Exchanges". World Federation of Exchanges. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

- Kraaijeveld, Kees (May 5, 2000). "iX, ieks of ai-iks?". de Volkskrant. Retrieved Aug 2, 2020.

- "Euronext va s'installer à la Défense en 2015". Le Figaro. Retrieved 2019-08-24.

- "Regulation". NYSE Euronext. Archived from the original on 2010-10-06. Retrieved 2010-09-23.

- "About Euronext". Euronext. Retrieved 2014-03-27.

- Joseph Penso de la Vega: Confusión de Confusiones; 1668, reprint Wiley, 1996.

- "Subscribe to read | Financial Times". www.ft.com. Retrieved Aug 2, 2020.

- "Breaking: Euronext Acquires 90% of FastMatch for $153m | Finance Magnates". Finance Magnates | Financial and business news. May 23, 2017. Retrieved Aug 2, 2020.

- "Euronext acquires 100 percent of Irish Stock Exchange in 'strategic' move".

- "Euronext completes the acquisition of Oslo Børs VPS | euronext.com". Retrieved Aug 2, 2020.

- Braudel, Fernand (1983). Civilization and capitalism 15th–18th century: The wheels of commerce. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0060150914.

- Stringham, Edward (2003). "The Extralegal Development of Securities Trading in Seventeenth Century Amsterdam". Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance. 43 (2): 321. doi:10.1016/S1062-9769(02)00153-9. SSRN 1676251.

- Vries, Jan de, and A. van der Woude. The First Modern Economy. Success, Failure, and Perseverance of the Dutch Economy, 1500–1815, (Cambridge University Press, 1997), ISBN 978-0-521-57825-7 p. 384–385

- The world’s first stock exchange: how the Amsterdam market for Dutch East India Company shares became a modern securities market, 1602–1700. L.O. The world’s first stock exchange: how the Amsterdam market for Dutch East India Company shares became a modern securities market, 1602–1700. L.O. Petram. FGw: Instituut voor Cultuur en Geschiedenis (ICG). 2011. FGw: Instituut voor Cultuur en Geschiedenis (ICG). 2011 2011 p. 2

- The world’s first stock exchange: how the Amsterdam market for Dutch East India Company shares became a modern securities market, 1602–1700. L.O. The world’s first stock exchange: how the Amsterdam market for Dutch East India Company shares became a modern securities market, 1602–1700. L.O. Petram. FGw: Instituut voor Cultuur en Geschiedenis (ICG). 2011. FGw: Instituut voor Cultuur en Geschiedenis (ICG). 2011 2011 20

- John F. Padgett, Walter W. Powell. The Emergence of Organizations and Markets. (Princeton University Press, 2012. Oct 14, 2012). ISBN 1400845556, 9781400845552 p. 227

- The world’s first stock exchange: how the Amsterdam market for Dutch East India Company shares became a modern securities market, 1602–1700. L.O. The world’s first stock exchange: how the Amsterdam market for Dutch East India Company shares became a modern securities market, 1602–1700. L.O. Petram. FGw: Instituut voor Cultuur en Geschiedenis (ICG). 2011. FGw: Instituut voor Cultuur en Geschiedenis (ICG). 2011 p.110

- The world’s first stock exchange: how the Amsterdam market for Dutch East India Company shares became a modern securities market, 1602–1700. L.O. The world’s first stock exchange: how the Amsterdam market for Dutch East India Company shares became a modern securities market, 1602–1700. L.O. Petram. FGw: Instituut voor Cultuur en Geschiedenis (ICG). 2011. FGw: Instituut voor Cultuur en Geschiedenis (ICG). 2011 p.41

- "Princess Máxima Opens new Amsterdam Trading Floor". nyx.com. Archived from the original on 5 September 2014.

- De la Vega, J. P. (1688). Fridson, Martin (ed.). Confusion de Confusiones (trans.) (1996 ed.). New York: Wiley.

- Kellenbenz, H. (1957). Introduction to Confusion de Confusiones (In M. Fridson (Ed.) Confusion de Confusiones ed.). New York: Wiley. pp. 125–146.

- J.G. van Dillen, ‘Termijnhandel te Amsterdam in de 16de en 17de eeuw’, De Economist 76 (1927) 503–523, there 503.

- The world’s first stock exchange: how the Amsterdam market for Dutch East India Company shares became a modern securities market, 1602–1700. L.O. The world’s first stock exchange: how the Amsterdam market for Dutch East India Company shares became a modern securities market, 1602–1700. L.O. Petram. FGw: Instituut voor Cultuur en Geschiedenis (ICG). 2011. FGw: Instituut voor Cultuur en Geschiedenis (ICG). 2011 p. 19

- The world’s first stock exchange: how the Amsterdam market for Dutch East India Company shares became a modern securities market, 1602–1700. L.O. The world’s first stock exchange: how the Amsterdam market for Dutch East India Company shares became a modern securities market, 1602–1700. L.O. Petram. FGw: Instituut voor Cultuur en Geschiedenis (ICG). 2011. FGw: Instituut voor Cultuur en Geschiedenis (ICG). 2011 p.19

- The world’s first stock exchange: how the Amsterdam market for Dutch East India Company shares became a modern securities market, 1602–1700. L.O. The world’s first stock exchange: how the Amsterdam market for Dutch East India Company shares became a modern securities market, 1602–1700. L.O. Petram. FGw: Instituut voor Cultuur en Geschiedenis (ICG). 2011. FGw: Instituut voor Cultuur en Geschiedenis (ICG). 2011 p. 30

- The world’s first stock exchange: how the Amsterdam market for Dutch East India Company shares became a modern securities market, 1602–1700. L.O. The world’s first stock exchange: how the Amsterdam market for Dutch East India Company shares became a modern securities market, 1602–1700. L.O. Petram. FGw: Instituut voor Cultuur en Geschiedenis (ICG). 2011. FGw: Instituut voor Cultuur en Geschiedenis (ICG). 2011 p.30

- Poel, Nana Van De. "The History Of La Bourse In 1 Minute". Culture Trip. Retrieved Aug 2, 2020.

- Ayers 2004, pp. 61–62.

- Colling, Alfred (1949). La Prodigieuse Histoire de la Bourse. Paris: Société d'éditions économiques et financières. p. 301.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- (in Portuguese) História da Bolsa de Valores de Lisboa Archived December 21, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, Millennium bcp

- "Euronext completes the acquisition of the Irish Stock Exchange – Irish Stock Exchange". www.ise.ie. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- "Amsterdam Stock Exchange". NYSE Euronext. Archived from the original on 2014-04-07. Retrieved 2014-03-27.

- Pownall, Grace; Maria Vulcheva; Xue Wang (1 March 2013). "Creation and Segmentation of the Euronext Stock Exchange and Listed Firms' Liquidity and Accounting Quality: Empirical Evidence": 7. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 4 April 2014. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Euronext – FXCM". FXCM Insights. 2016-05-04. Retrieved 2017-06-15.

- Agini, Samuel. "Euronext makes FX play with FastMatch buy". www.fnlondon.com. Retrieved 2018-12-19.

- "Euronext completes Irish Stock Exchange acquisition". Independent.ie. Retrieved 2018-12-19.

- MacDonald, A.; Manuel, G. (2006-12-12). "Nasdaq Formally Launches Bid for London Stock Exchange". The Wall Street Journal.

- "NYSE and Euronext 'set to merge'". BBC News. 2006-05-21. Retrieved 2006-05-22.

- "Deutsche Boerse outbids NYSE for Euronext merger". BBC News. May 23, 2006. Retrieved 2006-05-23.

- Lucchetti, Aaron; Macdonald, Alistair; Scannell, Kara (June 2, 2006). "NYSE, Euronext Set Plan to Form A Markets Giant". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2006-06-02.

- Taylor, Edward; Lucchetti, Aaron; Macdonald, Alistair (2006-11-15). "Deutsche Börse Is Exiting Euronext Chase". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2006-11-15.

- Lucchetti, Aaron; Macdonald, Alistair (2006-12-19). "Euronext Shareholders Approve Acquisition by NYSE". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2006-12-19.

- "Big Board Holders Back Euronext Deal". The New York Times. 2006-12-21. Retrieved 2006-12-21.

- Grant, Jeremy (2008-12-06). "Deutsche Börse pitches merger with NYSE Euronext". Financial Times. London. Retrieved 2008-12-09.

- Bunge, Jacob; Launder, William; Lucchetti, Aaron (2011-02-10). "NYSE, Deutsche Börse Talk Tie-Up as Competition Intensifies". The Wall Street Journal. Chicago: Lex Fenwick. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 2013-12-27.

- Waller, Martin (2008-12-08). "Talks to create world's biggest exchange". Times Online. London. Retrieved 2008-12-09.

- Bunge, Jacob (2011-07-15). "Deutsche Börse Wins 82% Backing for NYSE Deal". The Wall Street Journal. Chicago: Lex Fenwick. Retrieved 2013-12-27.

- Bartz, Diane (2011-12-11). "Deutsche Boerse, NYSE deal wins U.S. approval". Reuters. Washington D.C. Retrieved 2013-12-27.

- "Mergers: Commission blocks proposed merger between Deutsche Börse and NYSE Euronext" (Press release). European Commission. 2012-02-01. Retrieved 2013-12-27.

- "NYSE Euronext merger with Deutsche Boerse blocked by EU". BBC News. 2012-02-01. Retrieved 2013-12-27.

- "Deutsche Borse To Appeal EU Veto Of NYSE Euronext". International Business Times. March 20, 2012. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- Fairless, Tom (March 9, 2015). "EU Rejects Deutsche Börse Appeal Against Blocked Merger With NYSE-Euronext". Wall Street Journal. Dow Jones & Company. Retrieved January 6, 2016.

- "Euronext UK secures RIE status". FTSE Global Markets. June 4, 2014. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- McCrank, John; Jeffs, Luke (2012-12-20). "ICE to buy NYSE Euronext for $8.2 billion". Reuters. London. Retrieved 2013-12-27.

- Pisani, Bob (2013-06-03). "NYSE Euronext Shareholders Approve ICE Merger". CNBC. Retrieved 2013-12-27.

- "NYSE Euronext Shareholders Approve Acquisition by IntercontinentalExchange" (Press release). New York: NYSE Euronext. 2013-06-03. Archived from the original on 2013-12-28. Retrieved 2013-12-27.

- "IntercontinentalExchange Stockholders Approve Acquisition of NYSE Euronext" (Press release). Atlanta: ICE Intercontinental Exchange. 2013-06-03. Retrieved 2013-12-27.

- "Mergers: Commission approves acquisition of NYSE Euronext by InterContinental Exchange" (Press release). Brussels: European Commission. 2013-06-24. Retrieved 2013-12-27.

- "Self-Regulatory Organizations; New York Stock Exchange LLC; NYSE MKT LLC; NYSE Arca, Inc.; Order Granting Approval of Proposed Rule Change Relating to a Corporate Transaction in which NYSE Euronext Will Become a Wholly-Owned Subsidiary of IntercontinentalExchange Group, Inc" (PDF) (Press release). Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). 2013-08-15. Retrieved 2013-12-27.

- Bunge, Jacob (2013-08-16). "SEC Approves ICE-NYSE Deal". The Wall Street Journal. Chicago: Lex Fenwick. Retrieved 2013-12-27.

- Lynch, Sarah N.; McCrank, John (2013-08-16). McCormick, Gerald E.; Wallace, John (eds.). "SEC approves ICE's planned takeover of NYSE". Reuters. Retrieved 2013-12-27.

- "IntercontinentalExchange Completes Acquisition of NYSE Euronext" (Press release). ICE Intercontinental Exchange. 2013-11-13. Retrieved 2013-12-27.

- "ICE buys NYSE-Euronext. The end of the street". The Economist. New York: London, The Economist Newspaper Ltd. 2013 (November 16). 2013-11-16. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2013-12-27.

- "Euronext Detaches From ICE Through $1.2 Billion IPO". Bloomberg. June 20, 2014.

- "ICE to sell third of Euronext to institutions in pan-European IPO". Financial Times. May 27, 2014. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- "EnterNext, la Bourse des PME, devra convaincre". Le Monde. May 24, 2014. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- "Euronext modernises its markets to support growth of european companies | Euronext". www.euronext.com. Retrieved 2018-12-18.

- "Enternext". Europeanequities.nyx. Archived from the original on 2014-04-07. Retrieved 2014-03-27.

- https://www.euronext.com/fr/oslo-bors-vps-joins-euronext

- Euronext. "About Euronext". Archived from the original on 2014-01-12. Retrieved 2014-01-10.

- "NYSE Euronext opens 'NYSE Euronext London'". Automatedtrader. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- "NYSE Euronext to rival LSE for London listings". Reuters. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- Euronext. "Euronext Equities Product Directory". Retrieved 2014-01-11.

- Euronext. "Euronext Bonds Product Directory". Retrieved 2014-01-11.

- Euronext. "Euronext ETF Product Directory". Retrieved 2014-01-11.

- Euronext. "Euronext Funds Product Directory". Retrieved 2014-01-11.

- Euronext. "Euronext ETV/ENT Product Directory". Retrieved 2014-01-11.

- Euronext. "Euronext Warrants & Certificates Product directory". Archived from the original on 2013-10-20. Retrieved 2014-01-11.

- "Euronext signe un partenariat avec Dalian Commodity Exchange". L'Agefi. June 12, 2014. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- NYSE Euronext. "NYSE Euronext Global Derivatives Product Directory". Retrieved 2014-01-11.

- "Home Page – Official Website – Irish Stock Exchange". www.ise.ie. Retrieved 2017-03-16.

- http://www.ise.ie/Media/News-and-Events/2014/Facts-and-statistics-about-the-Irish-Stock-Exchange-its-listed-companies-and-related-securities-industry-October-2014.pdf?v=3122015

- "Equity Capital Markets: Atlantic Securities Market". Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- "Irish Stock Exchange – Companies". www.ise.ie. Retrieved 2017-03-16.

- "Bloxham won't be the last casualty of slump". Sunday Independent. 3 June 2012. Sunday Indo Business.

Will there even be a stand-alone Irish equity market in five years' time? The omens are not good.

- "World Federation of Exchanges". www.world-exchanges.org. Archived from the original on 7 March 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- "T+2 Standard settlement Lifecycle update". Euronext. 2014-07-28. Retrieved 2015-02-28.

- S.W.I.F.T. SCRL (2013-12-09). "ISO 10383 – Market Identifier Codes" (PDF). International Organization for Standardization. Retrieved 2014-01-06.

- Euronext. "Index Directory Euronext". Retrieved 2017-04-29.

- "Euronext to Partner with Degiro on Dutch Retail Investor Services". 22 September 2014.

- "Euronext Publishes Third Quarter 2014 Results". Reuters. 6 November 2014. Archived from the original on 12 April 2016.

- "Market Data | Euronext". www.euronext.com. Retrieved 2016-02-03.

- "Survey : Greeting". survey.constantcontact.com. Retrieved 2016-02-03.

- "Expanding Quandl's European Futures Data – Quandl Resource Hub". Quandl Resource Hub. Retrieved 2016-02-03.

- "Members list – EURONEXT". EURONEXT. Retrieved 2016-03-31.

External links

- Official website

- Yahoo! – Euronext NV Company Profile