Theophanu

Theophanu (German pronunciation: [te.ofaˈnuː]; also Theophania, Theophana, or Theophano; Medieval Greek Θεοφανώ;[1] c. AD 955 – 15 June 991) was empress of the Holy Roman Empire by marriage to Emperor Otto II, and regent of Empire during the minority of their son, Emperor Otto III, from 983 until her death in 991. She was the niece of the Byzantine Emperor John I Tzimiskes.

| Theophanu | |

|---|---|

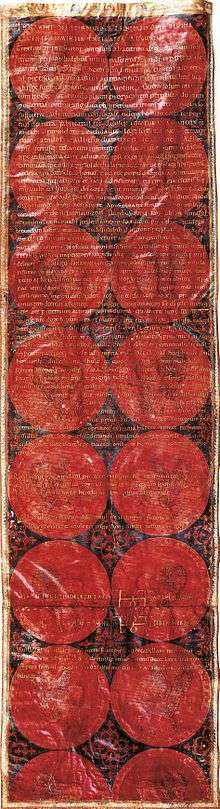

Christ blessing Otto (left) and Theophano (right), ivory book cover, dated 982/3, Musée de Cluny, Paris. | |

| Empress consort of the Holy Roman Empire | |

| Tenure | 973–983 |

| Queen consort of Germany | |

| Tenure | 972–983 |

| Coronation | 14 April 972 |

| Predecessor | Adelaide of Italy |

| Successor | Cunigunde of Luxembourg |

| Born | c. 955 possibly Constantinople |

| Died | 15 June 991 Nijmegen |

| Spouse | Otto II, Holy Roman Emperor (m. 972; died 983) |

| Issue more... | Adelaide I, Abbess of Quedlinburg Sophia I, Abbess of Gandersheim Mathilde, Countess Palatine of Lorraine Otto III, Holy Roman Emperor |

| Father | Constantine Skleros |

| Mother | Sophia Phokas |

Early life

According to the marriage certificate issued on 14 April 972 Theophanu is identified as the neptis (niece or granddaughter) of Emperor John I Tzimiskes (925–976, reigned 969–976) who was of Armenian descent. She was of distinguished noble heritage: the Vita Mahthildis identifies her as augusti de palatio and the Annales Magdeburgenses describe her as Grecam illustrem imperatoriae stirpi proximam, ingenio facundam.[2] Recent research tends to concur that she was most probably the daughter of Tzimiskes' brother-in-law (from his first marriage) Constantine Skleros (c. 920–989) and cousin Sophia Phokas, the daughter of Kouropalatēs Leo Phokas, brother of Emperor Nikephoros II (c. 912–969).[3][4][5][6]

Marriage

Theophanu was not born in the purple as the Ottonians would have preferred. The Saxon chronicler Bishop Thietmar of Merseburg writes that the Ottonian preference was for Anna Porphyrogenita, a daughter of late Emperor Romanos II. Theophanu's uncle John I Tzimiskes had overthrown his predecessor Nikephoros II Phokas in 969. Theophanu was escorted back to Rome for her wedding by a delegation of German and Italian churchmen and nobles. When the Ottonian court discovered Theophanu was not a scion of the Macedonian dynasty, as had been assumed, Otto I was told by some to send Theophanu away. His advisors believed that Theophanu's relation to the usurper John Tzimiskes would invalidate the marriage as a confirmation of Otto I as Holy Roman Emperor.[7]. He was persuaded to allow her to stay when it was pointed out that John Tzimiskes had wed Theodora, a member of the Macedonian dynasty and sister to Emperor Romanos II.[8] John was therefore was a Macedonian, by marriage if not by birth. Otto I must have been convinced, because Theophanu and Otto's heir, Otto II, were married on 14 April 972.

Otto I was told by some to send Theophanu away, on account of the notion that her questionable imperial origin would not legitimize the emperorship.[7]

A reference by the Pope to Emperor Nikephoros II as "Emperor of the Greeks"[9] in a letter while Otto's ambassador, Bishop Liutprand of Cremona, was at the Byzantine court, had destroyed the first round of marriage negotiations.[10] With the ascension of John I Tzimiskes, who had not been personally referred to other than as Roman Emperor, the treaty negotiations were able to resume. However, not until a third delegation led by Archbishop Gero of Cologne arrived in Constantinople, were they successfully completed. After the marriage negotiations completed, Theophanu and Otto II were married by Pope John XIII in April 972 and she was crowned as Holy Roman Empress the same day in Rome. According to Karl Leysers' book Communications and Power in Medieval Europe: Carolingian and Ottonian, Otto I's choice was not "to be searched for in the parlance of high politics" as his decision was ultimately made on the basis of securing his dynasty with the birth of the next Ottonian emperor.[7]

Empress

Otto II succeeded his father on 8 May 973. Theophanu accompanied her husband on all his journeys, and she is mentioned in approximately one quarter of the emperor's formal documents - evidence of her privileged position, influence and interest in affairs of the empire. It is known that she was frequently at odds with her mother-in-law, Adelaide of Italy, which caused an estrangement between Otto II and Adelaide. According to Abbot Odilo of Cluny, Adelaide was very happy when "that Greek woman" died.[11]

The Benedictine chronicler Alpert of Metz describes Theophanu as being an unpleasant and chattery woman.[11] Theophanu was also criticized for having introduced new luxurious garments and jewelry into France and Germany.[12] The theologian Peter Damian even asserts that Theophanu had a love affair with John Philagathos, a Greek monk who briefly reigned as Antipope John XVI.[13]

Otto II died suddenly on 7 December 983 at the age of 28, probably from malaria.[14] His three-year-old son, Otto III, had already been appointed King of the Romans during a diet held on Pentecost of that year at Verona. At Christmas, Theophanu had him crowned by the Mainz archbishop Willigis at Aachen Cathedral, with herself ruling as Empress Regent on his behalf. Upon the death of Emperor Otto II, Bishop Folcmar of Utrecht released his cousin, the Bavarian duke Henry the Quarrelsome from custody.[14] Duke Henry allied with Archbishop Warin of Cologne and seized his nephew Otto III in spring 984, while Theophanu was still in Italy. Nevertheless he was forced to surrender the child to his mother, who was backed by Archbishop Willigis of Mainz and Bishop Hildebald of Worms.

Regency

Theophanu ruled the Holy Roman Empire as regent for a span of five years, from May 985 to her death in 991, despite early opposition by the Ottonian court. In fact, many queens in the tenth century, on an account of male rulers dying early deaths, found themselves in power, creating an age of greater diversity. During her regency, Theophanu brought from her native east, a culture of royal women at the helm of a small amount of political power, something that the West--of which she was in rule of--had remained generally opposed to for centuries before her regency. Theophanu and her mother-in-law, Adelaide, are known during the empress' regency to have butted heads frequently--Adelaide of Italy is even quoted as referring to her as "that Greek empress."[15] Theophanu's rivalry with her mother-in-law, according to historian and author Simon Maclean, is overstated. Theophanu's "Greekness" was not an overall issue, moreover, there was a grand fascination with the culture surrounding Byzantine court in the west that slighted most criticisms to her Greek origin.[15]

Theophanu did not remain merely as an image of the Ottonian empire, but as an influence within the Holy Roman Empire. She intervened within the governing of the empire a total of seventy-six times during the reign of her husband Otto II—perhaps a foreshadowing of her regency.[7] Her first act as regent was in securing her son, Otto III, as the heir to the Holy Roman Empire. Theophanu also placed her daughters in power by giving them high positions in influential nunneries all around the Ottonian-ruled west, securing power for all her children.[7] She welcomed ambassadors, declaring herself "imperator" or "imperatrix", as did her relative contemporaries Irene of Athens and Theodora; the starting date for her reign being 972, the year of her marriage to the late Otto II.[16] Though never donning any armor, she also waged war and sought peace agreements throughout her regency.[17] Theophanu's regency is a time of considerable peace, as the years 985-991 passed without major crises. Though the myth of Theophanu's prowess as imperator could be an overstatement, according to historian Gerd Althoff, royal charters present evidence that magnates were at the core of governing the empire. Althoff remarks this as unusual, seeing that kings or emperors in the middle ages rarely shared such a large beacon of empirical power with nobility.[18]

Due to illness beginning in 988, Theophanu eventually died at Nijmegen and was buried in the Church of St. Pantaleon near her wittum in Cologne in 991.[19] The chronicler Thietmar eulogized her as follows: "Though [Theophanu] was of the weak sex she possessed moderation, trustworthiness, and good manners. In this way she protected with male vigilance the royal power for her son, friendly with all those who were honest, but with terrifying superiority against rebels."[20]

Because Otto III was still a child, his grandmother Adelaide of Italy took over the regency until Otto III became old enough to rule on his own.

Issue

- Adelaide I, Abbess of Quedlinburg and Gandersheim, born 973/974, died 1045.

- Sophia I, Abbess of Gandersheim and Essen, born October 975,[21] died 1039.

- Mathilde, born summer 978, died 1025; who married Ezzo, count palatine of Lotharingia.

- Otto III, Holy Roman Emperor, born end June/early July 980.

- A daughter, a twin to Otto, who died before October 8, 980.

References

- Θεοφανώ is a Greek diminutive of Θεοφάνεια "Theophany". G. S. Henrich, "Theophanu oder Theophano? Zur Geschichte eines 'gespaltenen' griechischen Frauennamensuffixes' in: Euw and Schreiner (eds.), Kaiserin Theophanu II (1991), 88–99.

- Hlawitschka, p.146

- Hlawitschka, pp. 145-153.

- Schwab (2009), p. 14

- Davids (2002), pp. 79–80

- Settipani, pp. 244-245.

- Leyser, Karl (1994). Communication and Power in Medieval Europe: The Carolingian and Ottonian Centuries. London, England: The Hambledon press. pp. 156–163. ISBN 1-85285-013-2.

- Norwich, John Julius (1993). Byzantium: The Apogee. London: Penguin. p. 220.

- Paul Collins. The Birth of the West: Rome, Germany, France, and the creation of Europe in the tenth century. p. 264, citing Liutprand of Cremona in The Works of Liutprand of Cremona, translation by F.A. Wright, London: George Routledge, 1930.

- Collins,page 264

- Davids (2002), p. 53.

- Davids (2002), p. 54.

- Davids (2002), pp. 56.

- Davids (2002), pp. 18, 36.

- Maclean, Simom (2017). Ottonian Queenship. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978--0--19--880010--1.

- Davids (2002), pp. 26, 38.

- Wangerin, Laura (December 2014). "Empress Theophanu, Sanctity, and Memory in Early Medieval Saxony". Central European History. 47: 716–717. doi:10.1017/s0008938914001927. JSTOR 43965083.

- Althoff, Gerd (2003). Otto III. University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press. pp. 40–42. ISBN 0-271-02232-9.

- Althoff, p.50.

- Davids (2002), p. 46.

- Seibert, Hubertus (1998). Otto II. Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB) Volume 19 (in German). Historische Kommission, Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften (BAdW). pp. 660–662.

Sources

- Davids, Adelbert. The Empress Theophano: Byzantium and the West at the turn of the first millennium, 2002. ISBN 0-521-52467-9

- Hlawitschka, Eduard, Die Ahnen der hochmitteralterlichen deutschen Konige, Kaiser und ihrer Gemahlinnen, Ein kommentiertes Tafelwerk, Band I: 911-1137, Teil 2, Hannover 2006. ISBN 978-3-7752-1132-1

- Hans K. Schulze, Die Heiratsurkunde der Kaiserin Theophanu, Hannover 2007 ISBN 978-3-7752-6124-1

- Schwab, Sandra (2009). Theophanu: eine oströmische Prinzessin als weströmische Kaiserin (in German). GRIN Verlag. ISBN 978-3-640-27041-5.

- Settipani, Christian, Continuité des élites à Byzance durant les siècles obscurs. Les princes caucasiens et l'Empire du VIe au IXe siècle, Boccard, Paris 2006. ISBN 978-2-7018-0226-8

- Sotiriades, Moses, "Theophanu, die Prinzessin aus Ost-Rom" in: von Steinitz, Peter (Editor), Theophanu, Regierende Kaiserin des Westreichs, Freundeskreis St. Pantaleon 2000. ISBN 3980519716

- Paul Collins. The Birth of the West: Rome, Germany, France, and the creation of Europe in the tenth century. Public Affairs, 2013. ISBN 978-1-61039-013-2

- Althoff, Gerd. ' 'Otto III' ', trans. Phyllis G. Jestice, 2003. ISBN 978-0-271-02401-1

External links

- Women's Biography: Theophanu, empress, contains several letters received by Theophanu.

| Royal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Adelaide of Italy |

Queen consort of Germany 972–983 |

Succeeded by Cunigunde of Luxembourg |

| Empress consort of the Holy Roman Empire 973–983 | ||