Same-sex marriage in the Netherlands

Same-sex marriage in the Netherlands has been legal since 1 April 2001.[1][2] A bill for the legalisation of such marriages was passed in the House of Representatives by 109 votes to 33 on 12 September 2000 and by the Senate by 49 votes to 26 on 19 December 2000. The law took effect on 1 April, which made the Netherlands the first country in the world to legalize same-sex marriage.

|

Civil unions and registered partnerships |

|

See also

|

|

Notes

* Not yet in effect or automatic deadline set by judicial body for same-sex marriage to become legal |

|

LGBT portal |

Unregistered partnership

Unregistered partnerships or informal cohabitation (samenwonen) occurs when same-sex or opposite-sex couples live together as a couple but choose to keep the legal status of their relationship unregistered or informal. This means all worldwide assets that belong to a single party remain the sole property of the party with no legal entitlement by the other party, whether owned before or acquired during the relationship. The couple can record a contract (samenlevingscontract) with a notary to receive some limited financial benefits, including for tax and pension purposes. However, the benefits are limited, e.g. the father or non-biological mother is not automatically recognized as a parent after the birth of a child, and upon the death of one of the partners, the other partner is not considered an heir.[3][4] This legal status of unregistered partnership is respected by Dutch courts.[5]

Registered partnership

On 1 January 1998, registered partnerships (Dutch: geregistreerd partnerschap)[lower-alpha 1] were introduced in Dutch law. The partnerships were meant for same-sex couples as an alternative to marriage, though they can also be entered into by opposite-sex couples, and in fact about one third of the registered partnerships between 1999 and 2001 were of opposite-sex couples.[9] In law, registered partnerships and marriage convey the same rights and duties, especially after some laws were changed to remedy inequalities with respect to inheritance and some other issues.[5]

Partnerships have become particularly common among Dutch couples, with about 18,000 new partnerships registered every year.[10]

Same-sex marriage

Legislative action

As early as the mid-1980s, a group of gay rights activists, headed by Henk Krol – then editor-in-chief of the Gay Krant – asked the government to allow same-sex couples to marry. Parliament decided in 1995 to create a special commission, which was to investigate the possibility of same-sex marriages. At that moment, the Christian Democrats (Christian Democratic Appeal) were not part of the ruling coalition for the first time since the introduction of full democracy. The special commission finished its work in 1997 and concluded that civil marriage should be extended to include same-sex couples. After the election of 1998, the Kok Government promised to tackle the issue. In September 2000, the final legislation draft was debated in the Dutch Parliament.

The marriage bill passed the House of Representatives by 109 votes to 33 on 12 September 2000.[11][12][13]

| Party | Voted for | Voted against | Absent (Did not vote) |

|---|---|---|---|

| G Labour Party (PvdA) | 41

|

1

|

3

|

| G People's Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD) | 36

|

– | |

| Christian Democratic Appeal (CDA) | 3

|

24

|

2

|

| G Democrats 66 (D66) | 14

|

– | – |

| GroenLinks (GL) | – | 1

| |

| Socialist Party (SP) | – | – | |

| Christian Union (CU) | – | – | |

| Reformed Political Party (SGP) | – | – | |

| Total | 109 | 33 | 8 |

- a. Was originally a member of the Reformatory Political Federation (RPF).

- b. Was originally a member of the Reformed Political League (GPV).

The Senate approved the bill on 19 December 2000 by 49 to 26 votes.[15][16] Only the Christian parties, which held 26 of the 75 seats at the time, voted against the bill. Although the Christian Democratic Appeal would form the next government, they did not indicate any intention to repeal the law.

| Party | Voted for | Voted against |

|---|---|---|

| Christian Democratic Appeal (CDA) | – | 20

|

| G People's Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD) | 19

|

– |

| G Labour Party (PvdA) | 15

|

– |

| GroenLinks (GL) | 8

|

– |

| G Democrats 66 (D66) | 4

|

– |

| Christian Union (CU) | – | |

| Socialist Party (SP) | 2

|

– |

| Reformed Political Party (SGP) | – | |

| Independent Senate Group (OSF) | 1

|

– |

| Total | 49 | 26 |

- a. Was originally a member of the Reformed Political League (GPV).

- b. Was originally a member of the Reformatory Political Federation (RPF).

The main article of the law changed article 1:30 of the Civil Code to read as follows:

- Een huwelijk kan worden aangegaan door twee personen van verschillend of van gelijk geslacht.

- (A marriage can be entered into by two persons of opposing or the same sex)

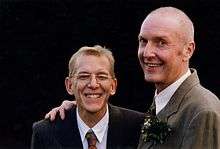

The law came into effect on 1 April 2001, and on that day four same-sex couples were married by the Mayor of Amsterdam, Job Cohen,[18][19] who became a registrar specifically to officiate at the weddings. A few months earlier, Mayor Cohen had been junior Minister of Justice of the Netherlands and was responsible for putting the new marriage and adoption laws through Parliament.

In Dutch, same-sex marriage is known as huwelijk tussen personen van gelijk geslacht or commonly homohuwelijk.[20][21]

Requirements and rights

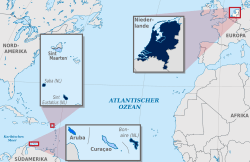

Dutch law requires that either partner have Dutch nationality or have residency in the Netherlands. The marriageable age in the Netherlands is 18, or below 18 with parental consent. The law is only valid in the European territory of the Netherlands and on the Caribbean islands of Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba, but does not apply to the other constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Netherlands.[22]

The single legal difference between same-sex marriages and heterosexual marriages was that, in the former case, parentage by both partners was not automatic. The legal mother of a child is its biological mother (article 1:198 of the civil law) and the father is (in principle) the man she is married to when the child is born. Moreover, the father must be a man (article 1:199). The other partner could thus become a legal mother only through adoption. Only in the case when a biological father did not become a parent (e.g. in case of artificial insemination by lesbian couples), would both female spouses obtain parental authority automatically (article 1:253sa). In December 2013, the Dutch Parliament changed this and allowed automatic parenthood for lesbian couples. The new law, which came into effect on 1 April 2014, allows the co-mother who is married to – or has a registered partnership with – the mother to be automatically recognized as the legal mother if the sperm donor was initially anonymous. In the case of a known donor, the biological mother decides whether the donor or the co-mother is the child's second legal parent.[23][24]

On 6 April 2016, Minister of Foreign Affairs Bert Koenders and Minister of Security and Justice Ard van der Steur confirmed the Dutch position that like other couples same-sex couples who are not Dutch residents or nationals cannot marry in the country. They said it will lead to practical and legal problems and could even be dangerous to some participants. The move came after the Liberal Democratic Party had asked the ministers to look into allowing non-resident foreigners to take advantage of the Netherlands' same-sex marriage law.[25]

Religious denominations

Since the mid-1960s, religious solemnizations of same-sex relationships have taken place in some Dutch churches.[26] The Dutch Remonstrants were Europe's first Christian denomination to officially allow such solemnizations in 1986.[27] Also, the Protestant Church in the Netherlands, the largest Protestant denomination in the Netherlands, has allowed their congregations to perform same-sex marriages since 2004.[28]

Aruba, Curaçao and Sint Maarten

In Aruba,[29] Curaçao,[30] and Sint Maarten,[30] separate civil codes exist in which rules for marriage are laid down and it is not possible to perform a same-sex marriage in these constituent countries.

All territories of the Kingdom of the Netherlands register same-sex marriages performed in the Netherlands proper as a result of a Dutch Supreme Court ruling. The Supreme Court ruled that all vital records recorded in the Kingdom of the Netherlands were valid throughout the Kingdom; this was based on its interpretation of the Charter for the Kingdom of the Netherlands. However, subsequent rulings have established that same-sex marriages are not automatically entitled to the same privileges (e.g., social security) extended to married couples of the opposite sex.[31][32][33]

Aruba legalised registered partnerships for both same-sex and opposite-sex couples in October 2016.[34]

Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba

Same-sex marriage became legal in Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba, which are three special municipalities of the Netherlands (also known as the Caribbean Netherlands), following the entry into force of a law enabling same-sex couples to marry there on 10 October 2012.[35][36]

Opposition

After the Dutch Parliament legalized same-sex marriage, the Protestant Church in the Netherlands permitted individual congregations to decide whether or not to bless such relationships as a union of love and faith before God, and in practice many churches now conduct such ceremonies.[37]

In 2007, controversy arose when the new Balkenende Government announced in its policy statement that officials who object to same-sex marriage on principle may refuse to marry such couples.[38] Some Socialist and Liberal dominated municipal councils opposed this policy, claiming that the job of a registrar is to marry all couples, not only opposite-sex couples.[39] The opposition parties stated that if a registrar opposed same-sex marriages, they should not hold that post.[40] The municipality of Amsterdam announced that they would not comply with this policy, and that registrars there would still be obliged to marry same-sex couples. In reaction to this, many other municipalities announced their rejection of this proposal as well. The Balkenende Government claimed that this issue lay solely within the remit of the central government. In practice, municipalities could decide whether or not to hire registrars who object to marrying same-sex couples.[41]

Before 2014, civil servants could refuse to marry same-sex couples as long as the municipality ensured that other civil servants were available to solemnize the marriage. In 2014, a law was passed that made it illegal for all marriage officiants to refuse their services to same-sex couples.[42]

Statistics

According to provisional figures from Statistics Netherlands, for the first six months, same-sex marriages made up 3.6% of the total number of marriages: a peak of around 6% in the first month followed by around 3% in the remaining months, about 1,339 male couples and 1,075 female couples in total.[43] By June 2004, more than 6,000 same-sex marriages had been performed in the Netherlands.[44]

In March 2006, Statistics Netherlands released estimates on the number of same-sex marriages performed each year: 2,500 in 2001, 1,800 in 2002, 1,200 in 2004, and 1,100 in 2005.[45]

From 2001 to 2011, 14,813 same-sex marriages were performed; 7,522 between two women and 7,291 between two men. In the same period, there were 761,010 heterosexual marriages. There were also 1,078 same-sex divorces.[46]

From 2001 to 2015, approximately 21,330 same-sex couples wed in the Netherlands. Of these, 11,195 were female couples and 10,135 were male couples.[43]

Public opinion

According to an Ifop poll, conducted in May 2013, 85% of the Dutch population supported allowing same-sex couples to marry and adopt children.[47]

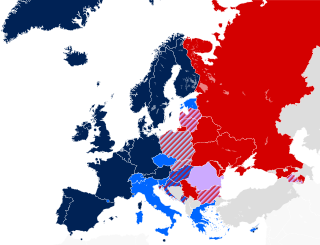

The 2015 Eurobarometer found that 91% of the Dutch population thought that same-sex marriage should be allowed throughout Europe, 7% were against.[48]

A Pew Research Center poll, conducted between April and August 2017 and published in May 2018, showed that 86% of Dutch people supported same-sex marriage, 10% were opposed and 4% didn't know or refused to answer.[49] When divided by religion, 95% of religiously unaffiliated people, 90% of non-practicing Christians and 60% of church-attending Christians supported same-sex marriage.[50] Opposition was also 10% among 18-34-year-olds.[51]

The 2019 Eurobarometer found that 92% of Dutch thought same-sex marriage should be allowed throughout Europe, 8% were against.[52]

See also

Notes

- West Frisian: registrearre partnerskip;[6]

Papiamento: union civil;[7]

Limburgish: geregistreerd partnersjap.[8]

References

- "Gay Marriage Goes Dutch". CBS News. Associated Press. 1 April 2001. Archived from the original on 28 January 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- "Same-Sex Marriage Legalized in Amsterdam". CNN. 1 April 2001. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- "Samenwonen". Notaris.nl (in Dutch). Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- "Wat zet ik in een samenlevingscontract?". Het Juridisch Loket (in Dutch). Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- Waaldijk, Kees. "Major legal consequences of marriage, cohabitation and registered partnership for different-sex and same-sex partners in the Netherlands" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- "Registrearre partnerskip hieltyd populêrder yn Fryslân". Omrop Fryslân (in Western Frisian). 25 August 2017.

- "Amienda pa permiti Union Civil casi no tin deferencia cu matrimonio". Diario Aruba (in Papiamento). 16 August 2016.

- "Heugem en Randwiek 9 jannewarie 1959 en 5 kier 11 plus twie" (PDF). www.dewaterratte.nl (in Limburgish).

- Dunbar, William. "Equal marriage around the world". Independent. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- "Privacy settings". myprivacy.dpgmedia.net.

- "Dutch Legislators Approve Full Marriage Rights for Gays". The New York Times. 13 September 2000. Archived from the original on 13 March 2016. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- "Netherlands legalizes gay marriage". BBC News. 12 September 2000. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- "Dutch legalise gay marriage". BBC News. 12 September 2000. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- "Aan de orde zijn de stemmingen in verband met het wetsvoorstel Wijziging van Boek 1 van het Burgerlijk Wetboek in verband met de openstelling van het huwelijk voor personen van hetzelfde geslacht (Wet openstelling huwelijk) (26672)" (in Dutch). Retrieved 31 January 2017.

- "Same-Sex Dutch Couples Gain Marriage and Adoption Rights". The New York Times. 20 December 2000. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- "Dutch gays allowed to marry". BBC News. 19 December 2000. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- "Aan de orde is de stemming over het wetsvoorstel Wijziging van Boek 1 van het Burgerlijk Wetboek in verband met de openstelling van het huwelijk voor personen van hetzelfde geslacht (Wet openstelling huwelijk) (26672)" (in Dutch). Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- "World's first legal gay weddings". Television New Zealand. 1 April 2001. Archived from the original on 5 February 2010. Retrieved 8 October 2009.

- "Dutch gay couples exchange vows". BBC News. 1 April 2001. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- "Huwelijk tussen personen van gelijk geslacht" (in Dutch). Government of the Netherlands. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011.

- "Frans homohuwelijk blijft verboden" (in Dutch). Nederlandse Omroep Stichting. 18 January 2011. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- "Getting married in the Netherlands". Expatica.

- "New law on lesbian parenthood and transgender individuals". Ru.nl. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- "Wet lesbisch ouderschap treedt in werking" (in Dutch). Government of the Netherlands. 1 April 2014. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- "Dutch gay marriage rights restricted to locals, wedding tourism ruled out". Dutch News. 6 April 2016.

- Bos, David J. (2 September 2017). ""Equal rites before the law": religious celebrations of same-sex relationships in the Netherlands, 1960s–1990s". Theology & Sexuality. 23 (3): 188–208. doi:10.1080/13558358.2017.1351123 – via Taylor and Francis+NEJM.

- "Remonstrants and Boomsma receive homo emancipation prize". Trouw (in Dutch). 25 January 2010. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- Andries, Jan (4 January 2007). "HET HOMOHUWELIJK EN DE KERK" (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- "Burgerlijk wetboek (Aruba), boek 1" (in Dutch). Government of Aruba. Archived from the original on 14 April 2011. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- "Burgerlijk wetboek van de Nederlandse Antillen, boek 1" (in Dutch). Government of the Netherlands. 31 August 2006. Archived from the original on 27 April 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- "hoger beroep zaak BM9524" (in Dutch). Jure.nl. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- "hoger beroep zaak BL1992" (in Dutch). Jure.nl. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- "hoger beroep zaak BI9335" (in Dutch). Jure.nl. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- "Parlement neemt amendement geregistreerd partnerschap aan". Caribisch Netwerk (in Dutch). 8 September 2016.

- "Burgerlijk wetboek BES, boek 1" (in Dutch). Government of the Netherlands. Archived from the original on 4 April 2016. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- "Aanpassingswet openbare lichamen Bonaire, Sint Eustatius en Saba" (in Dutch). Government of the Netherlands. 1 September 2010. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- "The Uniting Protestant Churches in the Netherlands and homosexuality". National Service Centre PCN. November 2004. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011.

- "Ambtenaren kunnen homo-huwelijk weigeren". FOK! (in Dutch). 2 March 2007. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- "PvdA en GroenLinks: ambtenaren mogen homohuwelijk niet weigeren". Algemeen Dagblad (in Dutch). 17 March 2007. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 17 October 2009.

- "Alle ambtenaren moeten homo's trouwen". Elsevier (in Dutch). 15 February 2007. Archived from the original on 6 February 2016.

- "Amsterdam wil sluiten homohuwelijk verplichten". Elsevier (in Dutch). 13 February 2007. Archived from the original on 9 March 2016.

- "Eerste Kamer der Staten-Generaal - Initiatiefvoorstel-Pia Dijkstra en Schouw Gewetensbezwaren ambtenaren van de burgerlijke stand (33.344)". www.eerstekamer.nl.

- "Lesbian couples likelier to break up than male couples". Cbs.nl. 30 March 2016. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- "Homosexual unions slowly gain momentum in Europe". GlobalGayz. Archived from the original on 17 August 2011.

- Thornberry, Malcolm (20 March 2006). "Netherlands' Gay Marriages Level Off". 365gay News. Archived from the original on 21 March 2006. Retrieved 17 October 2009.

- "Ten years of same-sex marriage: a mixed blessing". Radio Netherlands Worldwide. 1 April 2011. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- "Enquête sur la droitisation des opinions publiques européennes" (PDF). Ifop (in French). 16–29 May 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 February 2016. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- "Special Eurobarometer 437" (PDF). Eurobarometer. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 January 2016. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- Religion and society, Pew Research Center, 29 May 2018

- Being Christian in Western Europe, Pew Research Center, 29 May 2018

- Eastern and Western Europeans Differ on Importance of Religion, Views of Minorities, and Key Social Issues, Pew Research Center, 2017

- "Eurobarometer on Discrimination 2019: The social acceptance of LGBTI people in the EU". TNS. European Commission. p. 2. Retrieved 23 September 2019.