Sicambri

The Sicambri, also known as the Sugambri or Sicambrians, were a Celtic people or Germanic people who during Roman times lived on the east bank of the Rhine river, in what is now Germany, near the border with the Netherlands. They were first reported by Julius Caesar, who described them as Germanic (Germani), though he did not necessarily define this in terms of language.

Whether or not the Sicambri spoke a Germanic or Celtic language, or something else, is not certain, because they lived in the so-called Nordwestblock zone where these two language families came into contact and were both influential.

By the 3rd century the region, in which they and their neighbours had lived, had become part of the territory of the Franks, which was a new name that possibly represented a new alliance of older tribes, possibly including the Sicambri. Many Sicambri had however been moved into the Roman empire by this time.

History

The Sicambri appear in history around 55 BC, during the time of conquests of Gaul by Julius Caesar and his expansion of the Roman Empire. Caesar wrote in his Commentarii de Bello Gallico that near the confluence of the Rhine and Meuse River a battle took place in the land of the Menapii with a large number of Tencteri and Usipetes, who then proceeded to move south. When these two peoples were routed by Caesar, their cavalry escaped and found asylum back across the river with the Sicambri. Caesar then built a bridge across the river to punish the Sicambri. In 53 BC, Caesar confronted a raiding army of Sicambri who had crossed the Rhine to take advantage of the Roman war with the Eburones.

When Caesar defeated the Eburones, he invited all of the peoples that were interested to destroy the remainder. The Sicambri responded to Caesar's call. They took large amounts of cattle, slaves and plunder. Caesar commented that "these men are born for war and raids". "No swamp or marsh will stop them". After the raid on the Eburones they moved on against the Romans. They destroyed some of Caesar's units, in revenge for his campaign against them, and when the remains of the legion withdrew into the city of Atuatuca, the Sicambri went back across the Rhine.

Suetonius says that Augustus moved the Sicambri, presumably only a part of them, to the west bank of the Rhine, like the Ubii.[1]

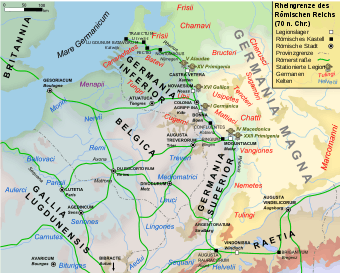

Claudius Ptolemy located the Sicambri, together with the Bructeri Minores, at the most northern part of the Rhine and south of the Frisii who inhabit the coast north of the river. Strabo located the Sicambri next to the Menapii, “who dwell on both sides of the river Rhine near its mouth, in marshes and low thorny woods. It is opposite to these Menapii that the Sicambri are situated". Strabo describes them as Germanic, and that beyond them are the Suevi and other peoples.[2]

Strabo mentions the positions of the Sicambri and Menapii near the Rhine, with the Suevi further inland, as described by Caesar, and perhaps this is intended to represent the historical positions.[3] Elsewhere Strabo mentions that the Rhine valley Germans have been mainly displaced: "there are but few remaining, and some portion of them are Sicambri". He apparently understood their position on the Rhine to literally be on the coast.[4] With the German wars still on-going in his time, he describes them as being one of the most well-known Germanic tribes in his time.[5]

In 16 BC their leader Melo, brother of Baetorix, organised a raid and defeated a Roman army under the command of Marcus Lollius, which sparked a reaction from the Roman Empire and helped start the series of Germanic Wars. Later the Sicambri under Deudorix, son of Baetorix, joined the rebellion of Arminius which subsequently annihilated the 3 Roman legions of Publius Quinctilius Varus.

In 12BC and 11 BC, the reported wars of Nero Claudius Drusus show that the tribe was living to the south of the Lippe river, with the Usipetes now settled to their north.[6] In 9 BC the Sicambri battled the Romans in an alliance with the Cherusci and Suevi and lost. At least a part was forced to move to the south side of the lower Rhine, where they possibly merged into Romanized populations such as the Tungri or Cugerni.[7]

The main part of the Sicambri "migrated deep into the country anticipating the Romans" according to Strabo. It has been suggested that the Marsi were a part of the Sicambri who managed to stay east of the Rhine after most had been moved from the area to join the Eburones and other Germani cisrhenani.[8]

In 26 AD some Sicambrian auxiliaries allied to Rome were involved in crushing an uprising of Thracian tribesmen.[9] By the time of Rome's conflict with the British Silures, Tacitus reports that the Sicambri were able to be mentioned as an historical example of a tribe who "had been formerly destroyed or transplanted into Gaul".[10]

Martial, in his Liber De Spectaculis, a series of epigrams written to celebrate the games in the Colosseum under Titus or Domitian, noted the attendance of numerous peoples, including the Sicambri: "With locks twisted into a knot, are come the Sicambrians..."[11]

Language

Like the Cimbri, and like their neighbours across the Rhine, the Eburones, many names of Sicambrian leaders end in typical Celtic suffixes like -rix (Baetorix, Deudorix, etc.). If the Sicambri were not Celtic speakers themselves, this could also indicate intense contacts with Celtic peoples across the Rhine in Gaul.

Sicambri as poetic name for Salian Franks

In Roman and Merovingian times, it was a custom to declare panegyrics. These poetic declarations were held for fun or propaganda to entertain guests and please rulers. Those panegyrics played an important role in the transmission of culture. One of the ritual customs of these poetic declarations is the use of archaic names for contemporary things. Romans were often called Trojans, and Salian Franks were called Sicambri. An example of this custom is remembered by the 6th-century historian Gregory of Tours (II, 31), who states that the Merovingian Frankish leader Clovis I, on the occasion of his baptism into the Catholic faith, was addressed as a Sicamber by Saint Remigius, the officiating bishop of Rheims. At the crucial moment of Clovis' baptism, Remigius declared, "Now you must bend down your head, you proud Sicamber. Honour what you have burnt. Burn what you have honoured." It is likely that this recalled a link between the Sicambri and the Salian Franks, who were Clovis' people.

More examples of Salians being called Sicamber can be found in the Panegyrici Latini, Life of King Sigismund, Life of King Dagobert and other old texts.

Sicambri in Frankish mythology

An anonymous work of 727 called Liber Historiae Francorum states that following the fall of Troy, 12,000 Trojans led by chiefs Priam and Antenor moved to the Tanais (Don) river, settled in Pannonia near the Sea of Azov and founded a city called Sicambria. In just 2 generations from the fall of Troy (by modern scholars dated in the late Bronze Age 1550-1200 BC) they arrived in the late 4th century AD at the Rhine. A variation of this story can also be read in Fredegar, and similar tales continue to crop up repeatedly throughout obscure, mediaeval-era European literature.

These stories have obvious difficulties. Historians, including eyewitnesses like Caesar, have given us accounts that place the Sicambri firmly at the delta of the Rhine, and archaeologists have confirmed ongoing settlement of peoples. Furthermore, the myth does not come from the Sicambri themselves, but from later Franks, and includes an incorrect geography.

Literature

- Heinrich, Johannes (2005). "Sugambrer". In Beck, Heinrich; Geuenich, Dieter; Steuer, Heiko (eds.). Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde [Dictionary of Germanic antiquity studies] (in German). 30. Berlin, New York: de Gruyter. ISBN 3110183854.

- Bruno Krüger (Hrsg.), Die Germanen – Geschichte und Kultur der germanischen Stämme in Mitteleuropa. Ein Handbuch in zwei Bänden. Bd. 1, 4. Auflage, Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1983 (Publications of the Central Institute for Ancient History and Archaeology of the Academy of Sciences of the GDR, Bd. 4).

- Alexander Sitzmann, Friedrich E. Grünzweig, Hermann Reichert (Hrsg.): Die altgermanischen Ethnonyme. Fassbaender, Wien 2008, ISBN 978-3-902575-07-4.

- Reinhard Wolters, Die Schlacht im Teutoburger Wald. Arminius, Varus und das römische Germanien. Beck, München 2008, ISBN 978-3-406-57674-4.

See also

- List of Germanic peoples

- Cimmerians

Notes

- Suetonius, Divus Augustus 21

- Strabo, "3", Geography, IV

- Strabo Book 4 chapter 3

- Strabo book 7 chap 1

- book 7 chap 2.

- Cassius Dio 54.32.

- Florus, II.30 (also here). Also see Orosius.

- J. N. Lanting & J. van der Plicht (Dec 15, 2010). "De ¹⁴C Chronologie van de Nederlandse Pre- en Protohistorie VI". Palaeohistoria. Barkhuis. 51/52. ISBN 9789077922736. Retrieved 2015-04-25.

- Tacitus, The Annals 4.47

- Tacitus, Annals, 12.39.

- Martial, Liber de spectaculis, epigram 3, line 9.

Sources

- Julius Caesar - Commentarii de Bello Gallico, particularly Book 6, Chapter 35

- Martial - Liber De Spectaculis, 3

- Tacitus - Annals

- Strabo - Geography

- Ptolemy - The Geography

- Fredegar - The 4th book of the chronicle of Fredegar with its continuations, translated by J. M. Wallace-Hadrill. Books on Demand, reprint 2005.

- Ian Wood - The Merovingian Kingdoms. Pearson Education, 1994.

External links

- Le mythe de l'origine troyenne (in French)

- Archaeological search for Sicambria (in Hungarian)