Operation Veritable

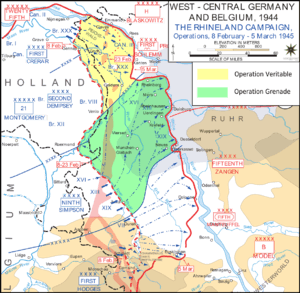

Operation Veritable (also known as the Battle of the Reichswald) was the northern part of an Allied pincer movement that took place between 8 February and 11 March 1945 during the final stages of the Second World War. The operation was conducted by Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery's Anglo-Canadian 21st Army Group, primarily consisting of the First Canadian Army under Lieutenant-General Harry Crerar and the British XXX Corps under Lieutenant-General Brian Horrocks.

Veritable was a northern pincer movement and started with XXX Corps advancing through the Reichswald (German: Imperial Forest) while the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division, in amphibious vehicles, cleared German positions in the flooded Rhine plain. The Allied advance proceeded more slowly than expected and at greater cost. This delayed the US offensive Operation Grenade, the southern pincer and at the same time allowed German forces under local German commander, Alfred Schlemm to be concentrated against the Commonwealth advance.

The fighting was hard, but the Allied advance continued. On 22 February, once clear of the Reichswald, and with the towns of Kleve and Goch in their control, the offensive was renewed as Operation Blockbuster and linked up with the U.S. Ninth Army near Geldern on 4 March after the execution of Operation Grenade.[2] Fighting continued as the Germans sought to retain a bridgehead on the west bank of the Rhine at Wesel and evacuate as many men and as much equipment as possible. Finally, on 10 March, the German withdrawal ended and the last bridges were destroyed.

Background

General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Allied Commander, had decided that the best route into Germany would be across the relatively flat lands of northern Europe, taking the industrial heartland of the Ruhr. This first required that Allied forces should close up to the Rhine along its whole length. Montgomery's 21st Army Group had established a front along the River Maas in late 1944 and had also considered several offensive operations to enlarge and defend the Nijmegen bridgehead and its important bridges (captured during the operation to capture Arnhem). One such proposal, Valediction (a development of an earlier plan; Wyvern) - an assault south-eastwards from Nijmegen between the Rhine and Maas rivers, initially had been shelved by Montgomery. A conference was convened at Maastricht on 7 December 1944 between Allied generals, to consider ways of maintaining pressure on the Germans throughout the winter. Consequently, Valediction was brought forward and allocated to the First Canadian Army. British XXX Corps were attached to the Canadians for the operation and the date was provisionally set as 1 January 1945. At this point, the name Veritable was attached to the operation in place of Valediction.[3]

In the event, Veritable was delayed by the diversion of forces to stem the German attack through the Ardennes in December, (Battle of the Bulge) and the advantages to the Allies of hard, frozen ground were lost.

The objective of the operation was to clear German forces from the area between the Rhine and Maas rivers, east of the German/Dutch frontier, in the Rhineland. It was part of Eisenhower's "broad front" strategy to occupy the entire west bank of the Rhine before its crossing. The Allied expectation was that the northern end of the Siegfried Line was less well defended than elsewhere and an outflanking movement around the line was possible and would allow an early assault against the industrial Ruhr region.

Veritable was the northern arm of a pincer movement. The southern pincer arm, Operation Grenade, was to be made by Lieutenant General William Hood Simpson's U.S. Ninth Army. The operation had complications. First, the heavily forested terrain, squeezed between the Rhine and Maas rivers, reduced Anglo-Canadian advantages in manpower and armour; the situation was exacerbated by soft ground which had thawed after the winter and also by the deliberate flooding of the adjacent Rhine flood plain.

Order of battle

Allied

At this stage, 21st Army Group consisted of the British Second Army (Lieutenant-General Miles C. Dempsey), First Canadian Army (Lieutenant-General Harry Crerar) and the U.S. Ninth Army (Lieutenant General William Simpson). In Veritable, the reinforced British XXX Corps (one of two such formations in the First Canadian Army), under Lieutenant-General Brian Horrocks, would advance through the Reichswald Forest and its adjacent flood plains to the Kleve – Goch road.

The First Canadian Army had had a severe time clearing the approaches to Antwerp during the previous autumn. It was, numerically, the smallest of the Allied armies in northern Europe and, despite its name, contained significant British units as part of its structure. For Veritable, it was further strengthened by XXX Corps. At the start of the operation, Allied deployment was, from left to right across the Allied front:

- 3rd Canadian Infantry Division (Major-General Daniel Spry)

- 2nd Canadian Infantry Division (Major-General Albert Bruce Matthews)

- 4th Canadian Armoured Division (Major-General Chris Vokes)

- 15th (Scottish) Infantry Division (Acting Major-General Colin Muir Barber)

- 53rd (Welsh) Infantry Division (Major General Robert Knox Ross)

- 51st (Highland) Infantry Division (Temporary Major-General Thomas Rennie)

Further divisions were committed as the operation progressed:

- 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division (Acting Lieutenant-General Ivor Thomas) – Part of XXX Corps' reserve at the start of the operation.

- Guards Armoured Division (Temporary Major-General Allan Adair) – Part of XXX Corps' reserve at the start of the operation.

- 11th Armoured Division (Temporary Major-General George Roberts) – transferred across the Maas from the British Second Army as the operation progressed.

German

Assessments by the German High Command were that an Allied advance through the Reichswald would be too difficult and the expected assault would be by the British Second Army from the Venlo area.[4] Reserves were therefore placed to respond to this. Alfred Schlemm, the local German commander, strongly disagreed, believing, correctly, that the Reichswald was the more likely route. He acted against the assessments of his superiors and therefore ensured that the area was well fortified, strengthened the Siegfried Line defences and quietly moved some of his reserves to be nearer this line of attack which meant that fresh, elite troops were readily available to him.

- 84th Infantry Division (Major-General Heinz Fiebig)

- This was an inexperienced and under-equipped division re-formed after its destruction at Falaise in Normandy. It was augmented by the well-equipped Luftwaffe 2nd Parachute Regiment, which was placed between the western tip of the Reichswald and the Maas. Two regiments, 1062nd Grenadier Regiment and 1051st Grenadier Regiment, covered the edge of the forest facing the Allies and the 1052nd Grenadier Regiment defended the Rhine flood plain on the German right. Two more, ineffective, units were held in the rear area: the Sicherungs Battalion Münster (a small unit of elderly men used to guard static installations) and the 276th Magen ("Stomach") Battalion, whose personnel had chronic digestive ailments that made them unsuited for active roles in the defence.

- 655th Heavy Anti-Tank Battalion

- Around 36 self propelled assault guns, the only German armour immediately available in the Reichswald.

- 180th Infantry Division (Klosterkemper)

- Guarding the Maas river bank, facing the British 2nd Army.

- Elements fought in defensive positions at Kleve and Goch.

- Elements in reserve at Geldern, as a result of Schlemm's expectation of an offensive through the Reichswald.

- 47th Panzer Corps (General Heinrich Freiherr von Lüttwitz)

- Army Group H's armoured reserve, at Dülken, south-east of Venlo. After the fighting in the Ardennes, its two divisions, the 116th Panzer and the 15th Panzer Grenadier, were at just over 50 per cent strength with no more than 90 tanks between them.

- 15th Panzer Grenadier Division (Wolfgang Maucke)

- A possible reserve formation, according to Allied assessments, that might be in place within six hours of the assault.

- 346th Division (Steinmueller)

Terrain

The Allied advance was from Groesbeek (captured during Operation Market Garden) eastwards to Kleve and Goch, turning south eastwards along the Rhine to Xanten and the US advance. The whole battle area was between the Rhine and Maas rivers, initially through the Reichswald and then across rolling agricultural country.

The Reichswald is a forested area close to the Dutch-German border. The Rhine flood plain, 2–3 miles (3.2–4.8 km) wide (and which, at the time of the operation, had been allowed to flood after a wet winter), is the northern boundary of the area and the Maas flood plain is the southern boundary. The Reichswald ridge is a glacial remnant which, when wet, easily turns to mud. At the time of the operation, the ground had thawed and was largely unsuitable for wheeled or tracked vehicles and these conditions caused breakdowns to significant numbers of tanks.

Routes through the forest were a problem for the Allies, both during their advance through the forest and later for supply and reinforcements. The only main roads passed to the north (Nijmegen to Kleve) and south (Mook to Goch) of the forest - no east-west metalled route passed through it. There were three north-south routes: two radiating from Hekkens to Kranenburg (between two and five kilometres behind the German frontline) and to Kleve; and Kleve to Goch, along the eastern edge of the Reichswald. The lack of suitable roads was made worse by the soft ground conditions and the deliberate flooding of the flood plains, which necessitated the use of amphibious vehicles. The few good roads were rapidly damaged and broken up by the constant heavy traffic that they had to carry during the assaults.

The Germans had built three defence lines. The first was from Wyler to the Maas along the western edge of the Reichswald, manned by the 84th Division and the 1st Parachute Regiment; this was a "trip-wire" line intended only to delay an assault and alert the main forces. The second, beyond the forest, was Rees, Kleve, Goch and the third ran from Rees, through the Uedemer Hochwald to Geldern.

Operation Veritable (Battle of the Reichswald)

Preparations for the operations were complicated by the poor condition of the few routes into the concentration area, its small size, the need to maintain surprise and, therefore, the need to conceal the movements of men and materiel. A new rail bridge was constructed that extended rail access to Nijmegen, a bridge was built across the Maas at Mook and roads were repaired and maintained.[5] Elaborate and strict restrictions were placed on air and daytime land movements; troop concentrations and storage dumps were camouflaged.

Operation Veritable was planned in three separate phases:

"Phase 1 The clearing of the Reichswald and the securing of the line Gennep-Asperden-Cleve.

"Phase 2 The breaching of the enemy's second defensive system east and south-east of the Reichswald, the capture of the localities Weeze-Üdem-Kalkar-Emmerich and the securing of the communications between them.

"Phase 3 The 'break-through' of the Hochwald 'lay-back' defence lines and the advance to secure the general line Geldern-Xanten."[6]

The operation started as an infantry frontal assault, with armoured support, against prepared positions, in terrain that favoured the defenders. On 7 February more than 750 RAF heavy bombers deluged Kleve and Goch with high explosive.[7][8] In order to reduce the defenders' advantages, a large scale artillery bombardment was employed, the biggest British barrage since the Second Battle of El Alamein. Men were literally deafened for hours by the noise of 1,034 guns.[9] It was hoped that this would not only destroy the German defences throughout the Reichswald but also destroy the defenders' morale and their will to fight. Air raids were also undertaken to isolate the battle area from further reinforcement.[10]

Operation Veritable began on 8 February 1945, at 10:30 five infantry divisions, 50,000 men with 500 tanks, attacked in line – respectively from the north, the 3rd and 2nd Canadian, the 15th (Scottish) in the center and the 53rd (Welsh) and 51st (Highland) on the right.[11] The next day the Germans released water from the largest Roer dam, sending water surging down the valley, and irreparably jammed the sluices to ensure a steady flow for many days. The next day they added to the flooding by doing the same to dams further upstream on the Roer and the Urft. The river rose at two feet an hour and the valley downstream to the Maas stayed flooded for about two weeks.

XXX Corps advanced with heavy fighting along the narrow neck of land between the Meuse and the Waal east of Nijmegen, but Operation Grenade had to be postponed for two weeks when the Germans released the waters from the Roer dams and river levels rose. The U.S. Ninth Army was unable to move and no military actions could proceed across the Roer until the water subsided. During the two weeks of flooding, Hitler forbade Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt to withdraw east behind the Rhine, arguing that it would only delay the inevitable fight. Rundstedt was ordered to fight where his forces stood. The imposed American standstill allowed German forces to be concentrated against the Anglo-Canadian assault.

At first, XXX Corps made rapid progress across most of its front but after the first day, German reinforcements appeared and violent clashes were reported with a regiment of the 6th Parachute Division and armored detachments. Horrocks ordered the 43rd (Wessex) Division to advance past Kleve into the German rear. This resulted in the greatest traffic jam in the history of modern warfare. With only one road available, units of the 43rd, 15th and Canadian divisions became inextricably mixed in a column 10 miles (16 km) long.[12] Two "natural" impediments to the Allied advance, flooding and the dense forest, failed to disrupt it.

The 15th Division had orders to capture Kleve, but on the night of 9 February they were held up on the outskirts. The 47 Panzer Corps under General Heinrich Freiherr von Lüttwitz was directed to Kleve and the Reichswald. On 11 February the 15th had cleared the town. Having expanded the front line to 14 miles (23 km), the II Canadian Corps, with the 2nd and 3rd Divisions and the 4th Armoured Division, became responsible for the drive along the Rhine to Kalkar and Xanten. XXX Corps were to operate on the right and take Goch before swinging towards the Rhine and linking with the Americans – once Operation Grenade had been launched.[13]

The 3rd Division used Buffalo amphibious vehicles to move through the flooded areas; the water rendered the German field defences and minefields ineffective and isolated their units on islands where they could be picked off, one by one. XXX Corps had rehearsed forest warfare tactics and were able to bring armour forward with them (despite a high rate of damage due to the natural conditions combined with the age of the tanks).[14] The German defences had not anticipated such tactics, so these tanks, including Churchill Crocodile flame-throwers, had great shock value.

Operation Blockbuster

Once the Reichswald had been taken, the Allied forces paused to regroup before continuing their advance towards the Hochwald forested ridge, plus Xanten to the east of it, and the US 9th Army. This stage was Operation Blockbuster. As planned, it would start on 22 February when the 15th (Scottish) Division would attack woods north-east of Weeze, to be followed two days later on the 24th when the 53rd (Welsh) Division would advance southwards from Goch, take Weeze and continue south-westward. Finally, the II Canadian Corps would launch, on 26 February, the operation intended to overcome the German defences based on the Hochwald and then exploit to Xanten.[15]

By the time the waters from the Roer dams had subsided and the US 9th Army was able to cross the Roer on 23 February, other Allied forces were also close to the Rhine's west bank. Rundstedt's divisions which had remained on the west bank of the Rhine were cut to pieces in the Rhineland and 230,000 men were taken prisoner.[16]

Aftermath

After the battle, 34 Armoured Brigade conducted a review of its own part in the forest phase of the battle, in order to highlight the experiences of the armoured units and learn lessons.[14]

After the war, Eisenhower commented this "was some of the fiercest fighting of the whole war" and "a bitter slugging match in which the enemy had to be forced back yard by yard". Montgomery wrote "the enemy parachute troops fought with a fanaticism un-excelled at any time in the war" and "the volume of fire from enemy weapons was the heaviest which had so far been met by British troops in the campaign."[17]

See also

Notes

Footnotes

- First Canadian Army losses from "8 February ... [to] ... 10 March were ... 1,049 officers and 14,585 other ranks; the majority of these were British soldiers". Canadian losses amounted to 379 officers and 4,925 other ranks, the vast majority being lost during Operation Blockbuster. Total allied losses in Operations Veritable/Blockbuster and Grenade amounted to 22,934 men.[1]

- Canadian First Army captured 22,239 prisoners during the operation, and the intelligence section estimated the number of German soldiers killed or made "long-term wounded" to have amounted to 22,000 men. In conjunction with Operation Grenade, the combined allied effort inflicted approximately 90,000 casualties on the German army.[1]

Citations

- Stacey, Chap 19, p. 522

- "Geilenkirchen to the Rhine". A Short History of the 8th Armoured Brigade. 2000. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

- Stacey, Chapter 17, pp 436 - 439

- Stacey, Chap 18, p 463

- Stacey, Chap 17, p 458

- Stacey, Chap 18, p 464

- Note, Kleve was bombed by a force of 295 Lancasters and 10 Mosquitoes of No. 1 and No. 8 Groups, Goch by 292 Halifaxes, 156 Lancasters and 16 Mosquitoes of No. 4, No. 6 and No. 8 Groups. The attack on Goch was stopped after 155 aircraft had bombed as the smoke from the resulting fires on the ground was stopping the Master Bomber from controlling the remaining crews bombing accurately. The attack on Kleve had been offered to Horrocks by the RAF, and he had accepted the offer, and was later to state it was "the most terrible decision I had ever taken in my life".

- Everitt, Chris; Middlebrook, Martin (2 April 2014). The Bomber Command War Diaries: An Operational Reference Book. ISBN 9781473834880.

- War Monthly (1976). Operation Veritable: A dirty slogging-match in the mud of the Rhineland, by William Moore (p. 2).

- Stacey, Chap 18, pp 465-466

- War Monthly (1976). Operation Veritable: A dirty slogging-match in the mud of the Rhineland, by William Moore (p. 3).

- War Monthly (1976). Operation Veritable: A dirty slogging-match in the mud of the Rhineland, by William Moore (pp. 3–5).

- War Monthly (1976). Operation Veritable: A dirty slogging-match in the mud of the Rhineland, by William Moore (p. 5).

- Veale, MC, Lt-Col P.N. "REPORT ON 34 ARMOURED BRIGADE OPERATIONS: The Reichswald Forest Phase, 8 to 17 February 1945". Retrieved 3 October 2013.

- Stacey, Chap 19

- Stacey, Chap 19, p 524

- Thacker, Toby (2006). The End of the Third Reich. Stroud: Tempus Publishing. pp. 92–93. ISBN 0-7524-3939-1.

References

- Stacey, Colonel Charles Perry; Bond, Major C.C.J. (1960). Official History of the Canadian Army in the Second World War: Volume III. The Victory Campaign: The operations in North-West Europe 1944–1945. The Queen's Printer and Controller of Stationery Ottawa.

- Chapter 17 "Winter on the Maas - 9 November 1944-7 February 1945". Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- Chapter 18: "The Battle of the Rhineland: Part I: Operation "VERITABLE", 8–21 February 1945". Retrieved 26 May 2009.

- Chapter 19: "The Battle of the Rhineland; Part II: Operation "BLOCKBUSTER", 22 February-10 March 1945". Retrieved 28 May 2009.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Operation Veritable. |