Otto van Veen

Otto van Veen, also known by his Latinized name Otto Venius or Octavius Vaenius (1556 – 6 May 1629), was a painter, draughtsman, and humanist active primarily in Antwerp and Brussels in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century. He is known for running a large studio in Antwerp, producing several emblem books, and for being, from 1594 or 1595 until 1598, Peter Paul Rubens's teacher. His role as a classically educated humanist artist (a pictor doctus), reflected in the Latin name by which he is often known, Octavius Vaenius, was influential on the young Rubens, who would take on that role himself.[1]

Otto van Veen | |

|---|---|

Otto van Veen, by Gertruida van Veen | |

| Born | 1556 |

| Died | 6 May 1629 (aged 72 or 73) |

| Nationality | Dutch |

| Known for | Painting |

Life

Van Veen was born around 1556 in Leiden, where his father, Cornelis Jansz. van Veen (1519–1591), had been Burgomaster.[2] He probably was a pupil of Isaac Claesz van Swanenburg until October 1572, when the Catholic family moved to Antwerp, and then to Liège. He studied for a time under Dominicus Lampsonius and Jean Ramey, before traveling to Rome around 1574 or 1575. He stayed there for about five years, perhaps studying with Federico Zuccari. Carel van Mander relates that van Veen then worked at the courts of Rudolf II in Prague and William V of Bavaria in Munich, before returning to the Low Countries.[3] In Brussels, he was court painter to the governor of the Southern Netherlands, Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma until 1592, and then active in Antwerp.

After becoming a master in the Guild of St. Luke in 1593, van Veen took numerous commissions for church decorations, including altarpieces for the Antwerp cathedral and a chapel in the city hall. He also organized his studio and workshop, which included Rubens. Van Veen's connection to Brussels remained, however, and when Archduke Ernest of Austria became governor in 1594, he may have aided the archduke in acquiring important Netherlandish paintings by the likes of Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Bruegel the Elder.[4] The artist later served as dean in two prominent organizations in the city, the Guild of St. Luke in 1602, and the Romanists in 1606.

In the seventeenth century, van Veen often worked for the Archdukes Albert and Isabella, but never as their court painter.[2] Later paintings include a series of twelve paintings depicting the battles of the Romans and the Batavians,[5] based on engravings he had already published of the subject, for the Dutch States General.[6] He had two brothers who were painters; Gijsbert van Veen (1558–1630) was a respected engraver and Pieter was an amateur.[3] His daughter Gertruid was also a painter,[7] and he was the uncle of three pastellists, Pieter's children, Apollonia, Symon, and Jacobus.[8] He died in Brussels.

Arnold Houbraken considered Van Veen to be the most impressive artist and scholar of his day and put his portrait on the title print of his three volume book De groote schouburgh der Nederlantsche konstschilders en schilderessen.[9]

Emblem books

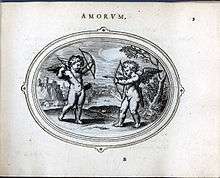

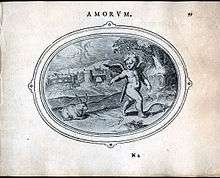

Increasingly, van Veen was active in producing Emblem books, including Quinti Horatii Flacci emblemata (1607), Amorum emblemata (1608), and Amoris divini emblemata (1615). In all these works, van Veen's skills as an artist and learned humanist are on display. The Amorum emblemata, for example, pictures 124 putti, or little cupids, enacting the mottoes and quotations from lyricists, philosophers, and ancient writers on the powers of Love. About van Veen's emblems Tina Montone has written, "In the course of the seventeenth century the Amorum emblemata was to become one of the most influential books of its time, functioning not only as a model for other Dutch and foreign emblem books, but also as a source of inspiration for many artists in other fields." [10] Some of these emblems are as relevant today as they would have to a seventeenth-century audience. A few examples of these mottoes read: "A Wished Warre: The woundes that lovers give are willingly receaved..." He goes on to quote Cicero and Seneca on this theme and depicts two Cupids exchanging arrows. Another example familiar to us today as the story of The Tortoise and the Hare (originally a fable by Aesop), is titled "Perseverance winneth: The hare and the tortes layd a wager of their speed ..." shows us a cupid and tortoise outpacing the hare and exemplifying the idea that the love which is steady and constant will ultimately win the race. [11]

Notes

- Belkin (1998): 26–28.

- Van de Velde.

- (in Dutch) Octavio van Veen in Karel van Mander's Schilderboeck, 1604, courtesy of the Digital library for Dutch literature

- Bertini (1998): 119.

- Brinio op het schild geheven Painting by Otto van Veen

- "Rijksmuseum". Archived from the original on 11 February 2012. Retrieved 18 May 2007.

- Gertruida van Veen(1602–1643) in the RKD

- Profile of Apollonia van Veen in the Dictionary of Pastellists Before 1800.

- (in Dutch) Octavio van Veen biography in De groote schouburgh der Nederlantsche konstschilders en schilderessen (1718) by Arnold Houbraken

- Montone, p. 47.

- Quotations from Veen, 1608

References

- Belkin, Kristin Lohse: Rubens. Phaidon Press, 1998. ISBN 0-7148-3412-2.

- Bertini, Giuseppe: "Otto van Veen, Cosimo Masi and the Art Market in Antwerp at the End of the Sixteenth Century." Burlington Magazine vol. 140, no. 1139. (Feb. 1998), pp. 119–120.

- Montone, Tina, "'Dolci ire, dolci sdegni, e dolci paci': The Role of the Italian Collaborator in the Making of Otto Vaenius's Amorum Emblemata," in Alison Adams and Marleen van der Weij, Emblems of the Low Countries: A Book Historical Perspective. Glasgow Emblem Studies, vol. 8. Glasgow: University of Glasgow, 2003. p.47.

- Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, Otto van Veen's Batavians defeating the Roman (sic)

- Van de Velde, Carl: "Veen [Vaenius; Venius], Otto van" Grove Art Online. Oxford University Press, [accessed 18 May 2007].

- Entry at the Netherlands Institute for Art History

- Veen, Otto van. Amorum Emblemata... Emblemes of Love, with verses in Latin, English, and Italian. Antwerp: [Typis Henrici Swingenii] Venalia apud Auctorem, 1608.

External links

- Othonis Vaenii emblemata

- Lambiek Comiclopedia article.

- Emblem Project Utrecht – 3 editions of emblem books by Otto van Veen

- Amorum Emblemata on Internet Archive.

- Vita D. Thomae Aquinatis a manuscript by Otto van Veen (1610)