Frans Hals

Frans Hals the Elder (UK: /hæls/,[1] US: /hɑːls, hælz, hɑːlz/,[2][3][4] Dutch: [frɑns ˈɦɑls]; c. 1582 – 26 August 1666) was a Dutch Golden Age painter, normally of portraits, who lived and worked in Haarlem.

Frans Hals | |

|---|---|

Copy of a self-portrait by Frans Hals | |

| Born | Frans Hals c. 1582 |

| Died | 26 August 1666 (aged 83–84) |

| Nationality | Dutch |

Notable work | The Gypsy Girl (1628) Laughing Cavalier (1624) |

He is known for his loose painterly brushwork, and helping introduce a lively style of painting to Dutch art. Hals played an important role in the evolution of 17th-century group portraiture.

Biography

Hals was born in 1582 or 1583 in Antwerp, then in the Spanish Netherlands, as the son of cloth merchant Franchois Fransz Hals van Mechelen (c. 1542–1610) and his second wife Adriaentje van Geertenryck.[5] Like many, Hals' parents fled during[6] the Fall of Antwerp (1584–1585) from the south to Haarlem in the new Dutch Republic in the north, where he lived for the remainder of his life. Hals studied under Flemish émigré Karel van Mander,[5][7] whose Mannerist influence, however, is barely noticeable in Hals' work.

In 1610, Hals became a member of the Haarlem Guild of Saint Luke, and he started to earn money as an art restorer for the city council. He worked on their large art collection that Karel van Mander had described in his Schilderboeck ("Painter's Book") published in Haarlem in 1604. The most notable of these were the works of Geertgen tot Sint Jans, Jan van Scorel, and Jan Mostaert that hung in the St John's Church in Haarlem. The restoration work was paid for by the city of Haarlem, since all Catholic religious art had been confiscated after the satisfactie van Haarlem had been reversed in 1578, which had formerly given Catholics equal rights to Protestants. However, the entire collection of paintings was not formally possessed by the city council until 1625, after the city fathers had decided which paintings were suitable for the city hall. The remaining art that was considered too "Roman Catholic" was sold to Cornelis Claesz van Wieringen, a fellow guild member, on the condition that he remove it from the city. It was in this cultural context that Hals began his career in portraiture, since the market had disappeared for religious themes.

The earliest known example of Hals' art is the portrait of Jacobus Zaffius (1611). His 'breakthrough' came with the life-sized group portrait The Banquet of the Officers of the St George Militia Company in 1616. His most noted portrait today is the one of René Descartes which he made in 1649.

Frans Hals married his first wife Anneke Harmensdochter around 1610. Frans was of Catholic birth, however, so their marriage was recorded in the city hall and not in church.[8] Unfortunately, the exact date is unknown because the older marriage records of the Haarlem city hall before 1688 have not been preserved.[8] Anneke was born 2 January 1590 as the daughter of bleacher Harmen Dircksz and Pietertje Claesdr Ghijblant, and her maternal grandfather, linen producer Claes Ghijblant of Spaarne 42, bequeathed the couple the grave in St Bavo's Church (Grote Kerk) where both are buried, though Frans took over 40 years to join his first wife there.[8] Anneke died in 1615, shortly after the birth of their third child and, of the three, Harmen survived infancy and one had died before Hals' second marriage.[8] As biographer Seymour Slive has pointed out, older stories of Hals abusing his first wife were confused with another Haarlem resident of the same name. Indeed, at the time of these charges, the artist had no wife to mistreat, as Anneke had died in May 1615.[9] Similarly, historical accounts of Hals' propensity for drink have been largely based on embellished anecdotes of his early biographers, namely Arnold Houbraken, with no direct evidence existing documenting such. After his first wife died, Hals took on the young daughter of a fishmonger to look after his children and, in 1617, he married Lysbeth Reyniers. They married in Spaarndam, a small village outside the banns of Haarlem, because she was already 8 months pregnant. Hals was a devoted father, and they went on to have eight children.[10]

Contemporaries such as Rembrandt moved their households according to the caprices of their patrons, but Hals remained in Haarlem and insisted that his customers come to him. According to the Haarlem archives, a schutterstuk that Hals started in Amsterdam was finished by Pieter Codde because Hals refused to paint in Amsterdam, insisting that the militiamen come to Haarlem to sit for their portraits. For this reason, we can be sure that all sitters were either from Haarlem or were visiting Haarlem when they had their portraits made.

Hals' work was in demand through much of his life, but he lived so long that he eventually went out of style as a painter and experienced financial difficulties. In addition to his painting, he worked as a restorer, art dealer, and art tax expert for the city councilors. His creditors took him to court several times, and he sold his belongings to settle his debt with a baker in 1652. The inventory of the property seized mentions only three mattresses and bolsters, an armoire, a table, and five pictures[11] (these were by himself, his sons, van Mander, and Maarten van Heemskerck).[12] Left destitute, he was given an annuity of 200 florins in 1664 by the municipality.[11]

The Dutch nation fought for independence during the Eighty Years' War,[11] and Hals was a member of the local schutterij, a military guild. He included a self-portrait in his 1639 painting of the St Joris company, according to its 19th-century painting frame. (It has not been possible to confirm this.) It was not common for ordinary members to be painted, as that privilege was reserved for the officers. Hals painted the company three times. He was also a member of a local chamber of rhetoric, and in 1644 he became chairman of the Guild of St Luke.

Frans Hals died in Haarlem in 1666 and was buried in the city's St Bavo's Church. He had been receiving a city pension, which was highly unusual and a sign of the esteem with which he was regarded. After his death, his widow applied for aid and was admitted to the local almshouse, where she later died.

Artistic career

Hals is best known for his portraits, mainly of wealthy citizens such as Pieter van den Broecke and Isaac Massa, whom he painted three times. He also painted large group portraits for local civic guards and for the regents of local hospitals. He was a Dutch Golden Age painter who practiced an intimate realism with a radically free approach. His pictures illustrate the various strata of society: banquets or meetings of officers, guildsmen,[11] local councilmen from mayors to clerks, itinerant players and singers, gentlemen, fishwives, and tavern heroes. In his group portraits, such as The Banquet of the Officers of the St Adrian Militia Company in 1627, Hals captures each character in a different manner. The faces are not idealized and are clearly distinguishable, with their personalities revealed in a variety of poses and facial expressions.

Hals was fond of daylight and silvery sheen, while Rembrandt used golden glow effects based upon artificial contrasts of low light in immeasurable gloom. Both men were painters of touch, but of touch on different keys – Rembrandt was the bass, Hals the treble. Hals seized a moment in the life of his subjects with rare intuition. What nature displayed in that moment he reproduced thoroughly in a delicate scale of color and with mastery over every form of expression. He became so clever that exact tone, light and shade, and modeling were obtained with a few marked and fluid strokes of the brush.[11] He became a popular portrait painter, and painted the wealthy of Haarlem on special occasions. He won many commissions for wedding portraits (the husband is traditionally situated on the left, and the wife situated on the right). His double portrait of the newly married Olycans hang side by side in the Mauritshuis, but many of his wedding portrait pairs have since been split up and are rarely seen together.

Wedding portraits

Portrait of Jacob Pietersz Olycan (1596–1638), 1625, Mauritshuis.

Portrait of Jacob Pietersz Olycan (1596–1638), 1625, Mauritshuis. Portrait of Aletta Hanemans (1606–1653), bride of Jacob Olycan, 1625, Mauritshuis.

Portrait of Aletta Hanemans (1606–1653), bride of Jacob Olycan, 1625, Mauritshuis. Paulus van Beresteyn, 1629, Louvre.

Paulus van Beresteyn, 1629, Louvre. Catharina Both van der Eem, bride of Paulus Beresteyn, 1629, Louvre.

Catharina Both van der Eem, bride of Paulus Beresteyn, 1629, Louvre. Joseph Coymans (1591–1660), the husband of Dorothea Berck, 1644, Wadsworth Atheneum.

Joseph Coymans (1591–1660), the husband of Dorothea Berck, 1644, Wadsworth Atheneum. Dorothea Berck (1593–1684), wife of Joseph Coymans, 1644, Private Collection.

Dorothea Berck (1593–1684), wife of Joseph Coymans, 1644, Private Collection. Portrait of Stephan Geraedts, husband of Isabella Coymans, 1652, Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp.

Portrait of Stephan Geraedts, husband of Isabella Coymans, 1652, Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp. Isabella Coymans, wife of Stephan Geraedts, 1652, Private Collection.

Isabella Coymans, wife of Stephan Geraedts, 1652, Private Collection.

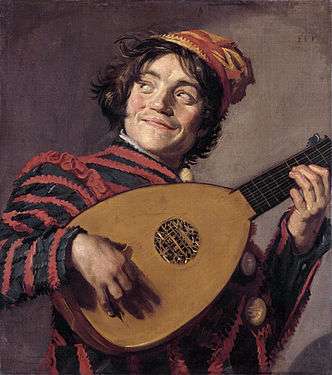

The only record of his work in the first decade of his independent activity is an engraving by Jan van de Velde copied from the lost portrait of The Minister Johannes Bogardus. Early works by Hals show him as a careful draughtsman capable of great finish yet spirited, such as Two singing boys with a lute and a music book and Banquet of the Officers of the St George Militia (1616). The flesh that he painted is pastose and burnished, less clear than it subsequently became. Later, he became more effective, displayed more freedom of hand and a greater command of effect.[11]

During this period, he painted the full-length portrait of Madame van Beresteyn (Louvre) and a full-length portrait of Willem van Heythuyzen leaning on a sword. Both these pictures are equalled by the other Banquet of the Officers of the St George Militia (with different portraits) and the same militia in 1627 and Banquet of the Officers of the St Hadrian Militia of 1633. A similar painting with the date of 1639 suggests some study of Rembrandt masterpieces, and a similar influence is apparent in a group portrait of 1641 representing the regents of the St Elisabeth Gasthuis and in his 1639 portrait of Maria Voogt at Amsterdam.[11]

From 1620 till 1640, he painted many double portraits of married couples on separate panels, the man on the left panel and his wife on the right panel. Only once did Hals portray a couple on a single canvas: Couple in a garden: Wedding portrait of Isaac Abrahamsz. Massa and Beatrix van der Laan, (c. 1622, Rijksmuseum Amsterdam).

His style changed throughout his life. Paintings of vivid color were gradually replaced by pieces where one color dominated: black. This was probably due to the sober dress of his Protestant sitters, more than any personal preference. One simple way to observe this change is to look at all of the portraits that he painted through the years with his trademark pose leaning over the back of a chair:

1626

1626 1631

1631 1633

1633 1635

1635 1645

1645 1645

1645.jpg) 1655

1655 1665

1665

Portrait painter

Later in his life, his brush strokes became looser, fine detail becoming less important than the overall impression. His earlier pieces radiated gaiety and liveliness, while his later portraits emphasized the stature and dignity of the people portrayed. This austerity is displayed in Regents of the St Elizabeth Hospital in 1641 and, two decades later, The Regents and Regentesses of the Old Men's Almshouse (c. 1664), which are masterpieces of color, though in substance all but monochromes. His restricted palette is particularly noticeable in his flesh tints, which became greyer from year to year, until finally the shadows were painted in almost absolute black, as in the Tymane Oosdorp.[11]

This tendency coincides with the period when Hals was less popular among the wealthy, and some historians have suggested that a reason for his predilection for black and white pigment was the low price of these colors as compared with the costly lakes and carmines.[11] Both conclusions are probably correct, however, because Hals did not travel to his sitters, unlike his contemporaries, but let them come to him. This was good for business because he was exceptionally quick and efficient in his own well-fitted studio, but it was bad for business when Haarlem fell on hard times.

As a portrait painter, Hals had scarcely the psychological insight of a Rembrandt or Velázquez, though in a few works, like the Admiral de Ruyter, the Jacob Olycan, and the Albert van der Meer paintings, he reveals a searching analysis of character which has little in common with the instantaneous expression of his so-called character portraits. In these, he generally sets upon the canvas the fleeting aspect of the various stages of merriment, from the subtle, half ironic smile that quivers round the lips of the curiously misnamed Laughing Cavalier to the imbecile grin of the Malle Babbe. To this group of pictures belong Baron Gustav Rothschilds Jester, the Bohemienne and the Laughing Fisherboy, whilst the Portrait of the Artist with his Second Wife, and the somewhat confused group of the Beresteyn Family at the Louvre show a similar tendency. Far less scattered in arrangement than this Beresteyn group, and in every respect one of the most masterly of Hals' achievements is the group called The Painter and his Family, which was almost unknown until it appeared at the winter exhibition at the Royal Academy in 1906.[11]

Many of Hals' works have disappeared, but it is not known how many. According to the Frans Hals catalog raisonné, 1974, 222 paintings can be ascribed to Hals. This list was compiled by Seymour Slive in 1970−1974 who also wrote an exhibition catalogue in 1989 and produced an update to his catalog raisonné work in 2014. In 1989 another authority on Hals, Claus Grimm, disagreed with Slive and published a lower list of 145 paintings in his Frans Hals. Das Gesamtwerk.

It is not known whether Hals ever painted landscapes, still lifes or narrative pieces, but it is unlikely. His debut for Haarlem society in 1616 with his large group portrait for the St George militia shows all three disciplines, but if that painting was his signboard for future commissions, it seems he was subsequently only hired for portraits. Many artists in the 17th century in Holland opted to specialise, and Hals also appears to have been a pure portrait specialist.

Painting technique

Hals was a master of a technique that utilized something previously seen as a flaw in painting, the visible brushstroke. The soft curling lines of Hals' brush are always clear upon the surface: "materially just lying there, flat, while conjuring substance and space in the eye."[13] Lively and exciting, the technique can appear "ostensibly slapdash"[13] – people often think that Hals 'threw' his works 'in one toss' (aus einem Guss) onto the canvas. This impression is not correct. True, the odd work was largely put down without underdrawings or underpainting ('alla prima'), but most of the works were created in successive layers, as was customary at that time. Sometimes a drawing was made with chalk or paint on top of a grey or pink undercoat, and was then more or less filled in, in stages. It does seem that Hals usually applied his underpainting very loosely: he was a virtuoso from the beginning. This applies, of course, particularly to his genre works and his somewhat later, mature works. Hals displayed tremendous daring, great courage and virtuosity, and had a great capacity to pull back his hands from the canvas, or panel, at the moment of the most telling statement. He didn't 'paint them to death', as many of his contemporaries did, in their great accuracy and diligence whether requested by their clients or not.

In the 17th century his first biographer, Schrevelius wrote: "An unusual manner of painting, all his own, surpassing almost everyone," on Hals' painting methods. For that matter, schematic painting was not Hals' own idea (the approach already existed in 16th century Italy), and Hals was probably inspired by Flemish contemporaries, Rubens and Van Dyck, in his painting method.

As early as the 17th century, people were struck by the vitality of Hals' portraits. For example, Haarlem resident Theodorus Schrevelius noted that Hals' works reflected 'such power and life' that the painter 'seems to challenge nature with his brush'. Centuries later Vincent van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo: 'What a joy it is to see a Frans Hals, how different it is from the paintings – so many of them – where everything is carefully smoothed out in the same manner.' Hals chose not to give a smooth finish to his painting, as most of his contemporaries did, but mimicked the vitality of his subject by using smears, lines, spots, large patches of color and hardly any details.

It was not until the 19th century that his technique had followers, particularly among the Impressionists. Pieces such as The Regentesses of the Old Men's Alms House and the civic guard paintings demonstrate this technique to the fullest.

Influence

Frans influenced his brother Dirck Hals (born at Haarlem, 1591–1656), who was also a painter.[14] Additionally, five of his sons became painters:

- Harmen Hals (1611–1669)

- Frans Hals the Younger (1618–1669)

- Jan Hals (1620–1654)

- Reynier Hals (1627–1672)

- Nicolaes Hals (1628–1686)

Though most of his sons became portrait painters, some of them took up still life painting or architectural studies and landscapes. Still lifes formerly attributed to his son Frans II have since been re-attributed to other painters, however.[5][15] Hals painted a young woman reaching into a basket in a still life market scene by Claes van Heussen.[16]

Other contemporary painters who took inspiration from Hals were, with the main cities they were based in:

- Jan Miense Molenaer (1609–1668), Haarlem and Amsterdam

- Judith Leyster (wife of Molenaer) (1609–1660), Haarlem and Amsterdam

- Adriaen van Ostade (1610–1685), Haarlem

- Adriaen Brouwer (1605–1638), mostly Antwerp

- Johannes Cornelisz Verspronck (1597–1662), Haarlem

- Bartholomeus van der Helst (1613–1670), Amsterdam

- Cornelis de Bie (1621–1664), Amsterdam

Hals had a large workshop in Haarlem and many students, though 19th century biographers questioned some of his pupils, since their painting styles were so dissimilar to Hals. In his De Groote Schouburgh (1718–21), Arnold Houbraken mentions Philips Wouwerman, Adriaen Brouwer, Pieter Gerritsz van Roestraten, Adriaen van Ostade and Dirck van Delen as students. Vincent Laurensz van der Vinne was also a student, according to his diary with notes left by his son Laurens Vincentsz van der Vinne. Roestraten was not only a student (the Haarlem archives contain a notarised document, which supports this fact), but he also became a son-in-law of Hals when he married his daughter Adriaentje. The Haarlem portrait painter, Johannes Verspronck, one of about 10 competing portraitists in Haarlem at the time, possibly studied for some time with Hals.

In terms of style, the closest to Hals' work is the handful of paintings that are ascribed to Judith Leyster, which she often signed. She also 'qualifies' as a possible student, as does her husband, the painter Jan Miense Molenaer.

Two centuries after his death, Hals received a number of 'posthumous' students. Claude Monet, Édouard Manet, Charles-François Daubigny, Max Liebermann, James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Gustave Courbet, and in the Netherlands, Jacobus van Looy and Isaac Israëls are some of the Impressionists and realists who have delved deeply into the work of Hals by making study copies of his work and further building on his techniques and style. Lovis Corinth named Hals as his biggest influence.[17] Many artists travelled to the Frans Hals Museum in Haarlem (since 1913 on the Groot Heiligland, and before that in the Town Hall), where several of his most important works are kept.

Legacy

Hals' reputation waned after his death and for two centuries he was held in such poor esteem that some of his paintings, which are now among the proudest possessions of public galleries, were sold at auction for a few pounds or even shillings. The portrait of Johannes Acronius realized five shillings at the Enschede sale in 1786. The portrait of the man with the sword at the Liechtenstein gallery sold in 1800 for 4, 5s.[11]

Starting at the middle of the 1860s his prestige rose again thanks to the efforts of critic Théophile Thoré-Bürger.[18] With his rehabilitation in public esteem came the enormous rise in value, and, at the Secretan sale in 1889, the portrait of Pieter van den Broecke was bid up to 4,420 francs, while in 1908 the National Gallery paid 25,000 pounds for the large family group from the collection of Lord Talbot de Malahide.[11]

Hals' work remains popular today, particularly with young painters who can find many lessons about practical technique from his unconcealed brushstrokes.[13] Hals' works have found their way to countless cities all over the world and into museum collections. From the late 19th century, they were collected everywhere—from Antwerp to Toronto, and from London to New York. Many of his paintings were then sold to American collectors.

A primary collection of his work is displayed in the Frans Hals Museum in Haarlem.

The Hals crater on Mercury is named in his honor.[19]

Hals was pictured on the Netherlands' 10-guilder banknote of 1968.[20]

The Banquet of the Officers of the St George Militia Company in 1616 appears on the restaurant wall in the 1989 Peter Greenaway film The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover.[21]

Catharina Hooft with her Nurse, c. 1619–1620

Catharina Hooft with her Nurse, c. 1619–1620

Three Children with a Goat Cart, c. 1620

Three Children with a Goat Cart, c. 1620 Portrait of a Man, 1630

Portrait of a Man, 1630- Jacobus Zaffius, 1611

Yonker Ramp and his sweetheart, 1623

Yonker Ramp and his sweetheart, 1623 Married Couple in a Garden, 1622

Married Couple in a Garden, 1622 Peeckelhaeringh, c. 1628–1630

Peeckelhaeringh, c. 1628–1630 The Mulatto, 1627

The Mulatto, 1627- Portrait of a Man Holding a Skull, c. 1615

Portrait of a Woman, 1644

Portrait of a Woman, 1644 The Merry Drinker, c. 1628–1630

The Merry Drinker, c. 1628–1630

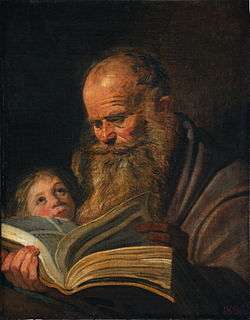

St Matthew, c. 1625

St Matthew, c. 1625 The Rommel Pot Player, c. 1618–1622

The Rommel Pot Player, c. 1618–1622

_-_Nationalmuseum_-_18571.tif.jpg) Daniel van Aken

Daniel van Aken.jpg) Portrait of René Descartes, c. 1649

Portrait of René Descartes, c. 1649

| External video | |

|---|---|

| |

Public collections (selection)

- Amsterdam Museum

- Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem

- Frick Collection, New York City

- Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerpen

- Louvre, Paris

- Mauritshuis, Den Haag

- Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

- Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam;[24]

- Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.[25]

- Kenwood House.[26]

References

- "Hals, Frans". Lexico UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- "Hals". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- "Hals". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- "Hals". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- Frans Hals iat the Netherlands Institute for Art History (in Dutch)

- Liedtke, Walter (August 2011). "Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History". metmuseum.org. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- Slive, Seymour, Frans Hals, and P. Biesboer (1989). Frans Hals. Munich: Prestel. p. 379.

- Anneke Harmensdr in Nieuwe gegevens betreffende Anneke Harmansdr., de eerste echtegonte van Frans Hals, by M. Thierry de Bye Dolleman working from research by C.A. de Goederen-van Hees, pp. 249-257, Haerlem : jaarboek 1973, ISSN 0927-0728, on the website of the North Holland Archives

- Slive, Seymour, Frans Hals, and Pieter Biesboer (1989). Frans Hals. Munich: Prestel. p. 376.

- see Hals biography in the Web Gallery of Art

-

- Slive, Seymour, Frans Hals, and P. Biesboer (1989). Frans Hals. Munich: Prestel. p. 406.

- Schjeldahl, Peter (8 August 2011). "Haarlem Shuffle: The Fast World of Frans Hals". The New Yorker. Condé Nast: 74–75. Retrieved 26 November 2011.(subscription required)

- Encyclopædia Britannica 1911 quote: "Quite in another form, and with much of the freedom of the elder Hals, Dirk Hals, his brother, painted festivals and ballrooms. But Dirk had too much of the freedom and too little of the skill in drawing which characterized his brother."

- Encyclopædia Britannica 1911 quote: "Of the master's numerous family members only Frans Hals the Younger (1618–1669) is notable, with paintings of cottages and poultry. A table laden with gold and silver dishes, cups, glasses and books, is considered one of his finest works."

- Young woman with a display of fruit and vegetables in the RKD

- Lovis Corinth A Feast of Painting, p17, Prestel, Vienna, 2009 ISBN 978-3-901508-64-6. ISBN 978-3-7913-4378-5

- Johnson, Paul. Art: A New History, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2003, p.369

- "Hals". Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature. NASA. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- Cuhaj, George S., ed. (2012). 2013 Standard Catalog of World Paper Money. Krause Publications. p. 713. ISBN 1440229562. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- Travers, Peter (6 April 1990). "The Cook, The Thief, His Wife and Her Lover". RollingStone. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- "Hals' Singing Boy with Flute". Smarthistory at Khan Academy. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- "Hals's Malle Babbe". Smarthistory at Khan Academy. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- Collection Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen

- Collection Rijksmuseum

Further reading

- (in Dutch) Frans Hals biography in De groote schouburgh der Nederlantsche konstschilders en schilderessen (1718) by Arnold Houbraken, courtesy of the Digital library for Dutch literature

- Seymour Slive: Frans Hals, 3 Volumes (oeuvre catalogue), New York / London 1970–1974

- Frans Hals (exhibition catalogue Washington/London/Haarlem, 1989.

- Claus Grimm published his Frans Hals. Das Gesamtwerk in 1989 (Stuttgart/Zürich; also translated into Dutch and English).

- N. Middelkoop and A. van Grevenstein, Frans Hals. Leven, werk, restauratie (Life, work and restorations) (Haarlem Amsterdam 1988). This work gives an account of restorations of the riflemen's pieces, but it also gives a picture of Hals' life and work.

- Antoon Erftemeijer; 2004 : Frans Hals in het Frans Hals Museum, Amsterdam/Gent (in Dutch, English and French), in which various chapters are devoted to Hals' life, his predecessors, portrait painting in the Golden Age, Hals' painting technique and other subjects. Many pictures with close-ups in this book show Hals' works in great detail.

- Christopher Atkins (2004) Frans Hals's Virtuoso Brushwork, Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek 2003, Zwolle, pp. 281–309).

Parts of this article are excerpts of The Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem, July 2005 by Antoon Erftemeijer, Frans Hals Museum curator.

- Henry R. Lew (2018) "imaging the World", Hybrid Publishers, Chapter 9 Frans Hals.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Frans Hals. |

- 27 paintings by or after Frans Hals at the Art UK site

- Frans Hals Museum in Haarlem

- Frans Hals Works, Biography and Style

- The National Gallery

- The Wallace Collection

- Web Gallery of Art (large collection of pictures and extensive biography)

- Frans Hals at zeno.org (in German)

- Olga's Gallery

- Works and literature on Frans Hals

- Walter Liedtke, "Frans Hals: Style and Substance" (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2011)