July Revolution

The French Revolution of 1830, also known as the July Revolution (révolution de Juillet), Second French Revolution or Trois Glorieuses in French ("Three Glorious [Days]"), led to the overthrow of King Charles X, the French Bourbon monarch, and the ascent of his cousin Louis Philippe, Duke of Orléans, who himself, after 18 precarious years on the throne, would be overthrown in 1848. It marked the shift from one constitutional monarchy, under the restored House of Bourbon, to another, the July Monarchy; the transition of power from the House of Bourbon to its cadet branch, the House of Orléans; and the replacement of the principle of hereditary right by popular sovereignty. Supporters of the Bourbon would be called Legitimists, and supporters of Louis Philippe Orléanists.

| Part of the Bourbon Restoration and the Revolutions of 1830 | |

Liberty Leading the People by Eugène Delacroix: an allegorical painting of the July Revolution. | |

| Date | 26–29 July 1830 |

|---|---|

| Location | France |

| Also known as | The July Revolution |

| Participants | French society |

| Outcome |

|

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of France | ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

20th century

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Timeline | ||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

Background

After Napoleonic France's defeat and surrender in May 1814, Continental Europe, and France in particular, was in a state of disarray. The Congress of Vienna met to redraw the continent's political map. Many European countries attended the Congress, but decision-making was controlled by four major powers: the United Kingdom, represented by its Foreign Secretary Viscount Castlereagh; the Austrian Empire, represented by the Chief Minister Prince Metternich; Russia, represented by Emperor Alexander I; and Prussia, represented by King Frederick William III.

France's foreign minister, Charles Maurice de Talleyrand, also attended the Congress. Although France was considered an enemy state, Talleyrand was allowed to attend the Congress because he claimed that he had only cooperated with Napoleon under duress. He suggested that France be restored to her "legitimate" (i.e. pre-Napoleonic) borders and governments—a plan that, with some changes, was accepted by the major powers. France was spared large annexations and returned to its 1791 borders. The House of Bourbon, deposed by the Revolution, was restored to the throne in the person of Louis XVIII. The Congress, however, forced Louis to grant a constitution, La Charte constitutionnelle.

Charles X's reign

On 16 September 1824, after a lingering illness of several months, the 68-year-old Louis XVIII died childless. Therefore, his younger brother, Charles, aged 66, inherited the throne of France. On 27 September Charles X made his state entry into Paris to popular acclaim. During the ceremony, while presenting the King the keys to the city, the comte de Chabrol, Prefect of the Seine, declared: "Proud to possess its new king, Paris can aspire to become the queen of cities by its magnificence, as its people aspire to be foremost in its fidelity, its devotion, and its love."[1]

Eight months later, the mood of the capital had sharply worsened in its opinion of the new king. The causes of this dramatic shift in public opinion were many, but the main two were:

- The imposition of the death penalty for anyone profaning the Eucharist (see Anti-Sacrilege Act).

- The provisions for financial indemnities for properties confiscated by the 1789 Revolution and the First Empire of Napoleon—these indemnities to be paid to anyone, whether noble or non-noble, who had been declared "enemies of the revolution."

Critics of the first accused the king and his new ministry of pandering to the Catholic Church, and by so doing violating guarantees of equality of religious belief as specified in La Charte.

The second matter, that of financial indemnities, was far more opportunistic than the first. This was because, since the restoration of the monarchy, there had been demands from all groups to settle matters of property ownership: to reduce, if not eliminate, the uncertainties in the real estate market[2] both in Paris and in the rest of France. But opponents, many of whom were frustrated Bonapartists, began a whispering campaign that Charles X was only proposing this in order to shame those who had not emigrated. Both measures, they claimed, were nothing more than clever subterfuge meant to bring about the destruction of La Charte.

Up to this time, thanks to the popularity of the constitution and the Chamber of Deputies with the people of Paris, the king's relationship with the élite—both of the Bourbon supporters and Bourbon opposition—had remained solid. This, too, was about to change. On 12 April, propelled by both genuine conviction and the spirit of independence, the Chamber of Deputies roundly rejected the government's proposal to change the inheritance laws. The popular newspaper Le Constitutionnel pronounced this refusal "a victory over the forces of counter-revolutionaries and reactionism."[3]

The popularity of both the Chamber of Peers and the Chamber of Deputies skyrocketed, and the popularity of the king and his ministry dropped. This became unmistakable when on 16 April 1827, while reviewing the Garde Royale in the Champ de Mars, the king was greeted with icy silence, many of the spectators refusing even to remove their hats. Charles X "later told [his cousin] Orléans that, 'although most people present were not too hostile, some looked at times with terrible expressions'."[4]

Because of what it perceived to be growing, relentless, and increasingly vitriolic criticism of both the government and the Church, the government of Charles X introduced into the Chamber of Deputies a proposal for a law tightening censorship, especially in regard to the newspapers. The Chamber, for its part, objected so violently that the humiliated government had no choice but to withdraw its proposals.

On 17 March 1830, the majority in the Chamber of Deputies passed a motion of no confidence, the Address of the 221, against the king and Polignac's ministry. The following day, Charles dissolved parliament, and then alarmed the Bourbon opposition by delaying elections for two months. During this time, the liberals championed the "221" as popular heroes, whilst the government struggled to gain support across the country as prefects were shuffled around the departments of France. The elections that followed returned an overwhelming majority, thus defeating the government. This came after another event: on the grounds that it had behaved in an offensive manner towards the crown, on 30 April the king abruptly dissolved the National Guard of Paris, a voluntary group of citizens and an ever reliable conduit between the monarchy and the people. Cooler heads were appalled: "[I] would rather have my head cut off", wrote a noble from the Rhineland upon hearing the news, "than have counseled such an act: the only further measure needed to cause a revolution is censorship."[5]

That came on Sunday, 25 July 1830 when he set about to alter the Charter of 1814 by decree. These decrees, known as the July Ordinances, dissolved the Chamber of Deputies, suspended the liberty of the press, excluded the commercial middle-class from future elections, and called for new elections. On Monday 26 July, they were published in the leading conservative newspaper in Paris, Le Moniteur. On Tuesday 27 July, the revolution began in earnest Les trois journées de juillet, and the end of the Bourbon monarchy.

The Three Glorious Days

Monday, 26 July 1830

It was a hot, dry summer, pushing those who could afford it to leave Paris for the country. Most businessmen could not, and so were among the first to learn of the Saint-Cloud "Ordinances", which banned them from running as candidates for the Chamber of Deputies, membership of which was indispensable to those who sought the ultimate in social prestige. In protest, members of the Bourse refused to lend money, and business owners shuttered their factories. Workers were unceremoniously turned out into the street to fend for themselves. Unemployment, which had been growing through early summer, spiked. "Large numbers of... workers therefore had nothing to do but protest."[6]

While newspapers such as the Journal des débats, Le Moniteur, and Le Constitutionnel had already ceased publication in compliance with the new law, nearly 50 journalists from a dozen city newspapers met in the offices of Le National. There they signed a collective protest, and vowed their newspapers would continue to run.[7]

That evening, when police raided a news press and seized contraband newspapers, they were greeted by a sweltering, unemployed mob angrily shouting, "À bas les Bourbons!" ("Down with the Bourbons!") and "Vive la Charte!" ("Long live the Charter!"). Armand Carrel, a journalist, wrote in the next day's edition of Le National:

France... falls back into revolution by the act of the government itself... the legal regime is now interrupted, that of force has begun... in the situation in which we are now placed obedience has ceased to be a duty... It is for France to judge how far its own resistance ought to extend.[8]

Despite public anger over the police raid, Jean-Henri-Claude Magin, the Paris Préfet de police, wrote that evening: "the most perfect tranquility continues to reign in all parts of the capital. No event worthy of attention is recorded in the reports that have come through to me."[9]

Tuesday, 27 July 1830: Day One

Throughout the day, Paris grew quiet as the milling crowds grew larger. At 4:30 pm commanders of the troops of the First Military division of Paris and the Garde Royale were ordered to concentrate their troops, and guns, on the Place du Carrousel facing the Tuileries, the Place Vendôme, and the Place de la Bastille. In order to maintain order and protect gun shops from looters, military patrols throughout the city were established, strengthened, and expanded. However, no special measures were taken to protect either the arm depots or gunpowder factories. For a time, those precautions seemed premature, but at 7:00 pm, with the coming of twilight, the fighting began. "Parisians, rather than soldiers, were the aggressor. Paving stones, roof tiles, and flowerpots from the upper windows... began to rain down on the soldiers in the streets".[10] At first, soldiers fired warning shots into the air. But before the night was over, twenty-one civilians were killed. Rioters then paraded the corpse of one of their fallen throughout the streets shouting "Mort aux Ministres! À bas les aristocrates!" ("Death to the ministers! Down with the aristocrats!")

One witness wrote:

[I saw] a crowd of agitated people pass by and disappear, then a troop of cavalry succeed them... In every direction and at intervals... Indistinct noises, gunshots, and then for a time all is silent again so for a time one could believe that everything in the city was normal. But all the shops are shut; the Pont Neuf is almost completely dark, the stupefaction visible on every face reminds us all too much of the crisis we face....[11]

In 1828, the city of Paris had installed some 2,000 street lamps. These lanterns were hung on ropes looped-on-looped from one pole to another, as opposed to being secured on posts. The rioting lasted well into the night until most of them had been destroyed by 10:00 PM, forcing the crowds to slip away.

Wednesday, 28 July 1830: Day Two

Fighting in Paris continued throughout the night. One eyewitness wrote:

It is hardly a quarter past eight, and already shouts and gun shots can be heard. Business is at a complete standstill.... Crowds rushing through the streets... the sound of cannon and gunfire is becoming ever louder.... Cries of "À bas le roi !', 'À la guillotine!!" can be heard....[12]

Charles X ordered Maréchal Auguste Marmont, Duke of Ragusa, the on-duty Major-General of the Garde Royale, to repress the disturbances. Marmont was personally liberal, and opposed to the ministry's policy, but was bound tightly to the King because he believed such to be his duty; and possibly because of his unpopularity for his generally perceived and widely criticized desertion of Napoleon in 1814. The king remained at Saint-Cloud, but was kept abreast of the events in Paris by his ministers, who insisted that the troubles would end as soon as the rioters ran out of ammunition.

Marmont's plan was to have the Garde Royale and available line units of the city garrison guard the vital thoroughfares and bridges of the city, as well as protect important buildings such as the Palais Royal, Palais de Justice, and the Hôtel de Ville. This plan was both ill-considered and wildly ambitious; not only were there not enough troops, but there were also nowhere near enough provisions. The Garde Royale was mostly loyal for the moment, but the attached line units were wavering: a small but growing number of troops were deserting; some merely slipping away, others leaving, not caring who saw them.

In Paris, a committee of the Bourbon opposition, composed of banker-and-kingmaker Jacques Laffitte, Casimir Perier, Generals Étienne Gérard and Georges Mouton, comte de Lobau, among others, had drawn up and signed a petition in which they asked for the ordonnances to be withdrawn. The petition was critical "not of the King, but his ministers", thereby countering the conviction of Charles X that his liberal opponents were enemies of his dynasty.[13]

After signing the petition, committee members went directly to Marmont to beg for an end to the bloodshed, and to plead with him to become a mediator between Saint-Cloud and Paris. Marmont acknowledged the petition, but stated that the people of Paris would have to lay down arms first for a settlement to be reached. Discouraged but not despairing, the party then sought out the king's chief minister, de Polignac – "Jeanne d'Arc en culottes". From Polignac they received even less satisfaction. He refused to see them, perhaps because he knew that discussions would be a waste of time. Like Marmont, he knew that Charles X considered the ordonnances vital to the safety and dignity of the throne of France. Thus, the King would not withdraw the ordonnances.

At 4 pm, Charles X received Colonel Komierowski, one of Marmont's chief aides. The colonel was carrying a note from Marmont to his Majesty:

Sire, it is no longer a riot, it is a revolution. It is urgent for Your Majesty to take measures for pacification. The honour of the crown can still be saved. Tomorrow, perhaps, there will be no more time... I await with impatience Your Majesty's orders.[14]

The king asked Polignac for advice, and the advice was to resist.

Thursday, 29 July 1830: Day Three

"They (the king and ministers) do not come to Paris", wrote the poet, novelist and playwright Alfred de Vigny, "people are dying for them ... Not one prince has appeared. The poor men of the guard abandoned without orders, without bread for two days, hunted everywhere and fighting."[15]

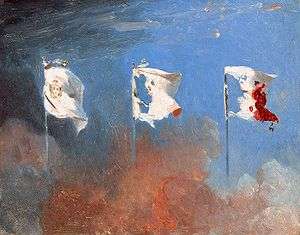

Perhaps for the same reason, royalists were nowhere to be found; perhaps another reason was that now the révoltés were well organized and very well armed. In only a day and a night, over 4,000 barricades had been thrown up throughout the city. The tricolor flag of the revolutionaries – the "people's flag" – flew over buildings, an increasing number of them important buildings.

Marmont lacked either the initiative or the presence of mind to call for additional troops from Saint-Denis, Vincennes, Lunéville, or Saint-Omer; neither did he ask for help from reservists or those Parisians still loyal to Charles X. The Bourbon opposition and supporters of the July Revolution swarmed to his headquarters demanding the arrest of Polignac and the other ministers, while supporters of the Bourbon and city leaders demanded he arrest the rioters and their puppet masters. Marmont refused to act on either request, instead awaiting orders from the king.

By 1:30 pm, the Tuileries Palace had been sacked. "A man wearing a ball dress belonging to the duchesse de Berry, with feathers and flowers in his hair, screamed from a palace window: 'Je reçois! Je reçois!' ('I receive! I receive!') Others drank wine from the palace cellars."[16] Earlier that day, the Louvre had fallen, even more quickly. The Swiss Guards, seeing the mob swarming towards them, and manacled by the orders of Marmont not to fire unless fired upon first, ran away. They had no wish to share the fate of a similar contingent of Swiss Guards back in 1792, who had held their ground against another such mob and were torn to pieces. By mid-afternoon, the greatest prize, the Hôtel de Ville, had been captured. The amount of looting during these three days was surprisingly small; not only at the Louvre—whose paintings and objets d'art were protected by the crowd—but the Tuileries, the Palais de Justice, the Archbishop's Palace, and other places as well.

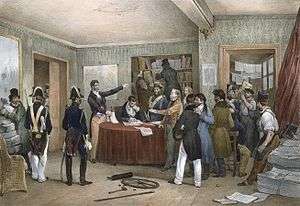

A few hours later, politicians entered the battered complex and set about establishing a provisional government. Though there would be spots of fighting throughout the city for the next few days, the revolution, for all intents and purposes, was over.

Result

The revolution of July 1830 created a constitutional monarchy. On 2 August, Charles X and his son the Dauphin abdicated their rights to the throne and departed for Great Britain. Although Charles had intended that his grandson, the Duke of Bordeaux, would take the throne as Henry V, the politicians who composed the provisional government instead placed on the throne a distant cousin, Louis Philippe of the House of Orléans, who agreed to rule as a constitutional monarch. This period became known as the July Monarchy. Supporters of the exiled senior line of the Bourbon dynasty became known as Legitimists.

The July Column, located on Place de la Bastille, commemorates the events of the Three Glorious Days.

This renewed French Revolution sparked an August uprising in Brussels and the Southern Provinces of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, leading to separation and the establishment of the Kingdom of Belgium. The example of the July Revolution also inspired unsuccessful revolutions in Italy and the November Uprising in Poland.

Two years later, Parisian republicans, disillusioned by the outcome and underlying motives of the uprising, revolted in an event known as the June Rebellion. Although the insurrection was crushed within less than a week, the July Monarchy remained doubtfully popular, disliked for different reasons by both Right and Left, and was eventually overthrown in 1848.

Gallery

.jpg) Jean-Baptiste Goyet, Une Famille Parisienne (le 28 Juillet 1830), 1830.

Jean-Baptiste Goyet, Une Famille Parisienne (le 28 Juillet 1830), 1830. Jean-Baptiste Goyet, Une Famille Parisienne (le 30 Juillet 1830), 1830.

Jean-Baptiste Goyet, Une Famille Parisienne (le 30 Juillet 1830), 1830.

References

- Mansel, Philip, Paris Between Empires (St. Martin's Press, New York 2001) p.198

- Mansel, Philip, Paris Between Empires (St. Martin Press, New York 2001) p.200

- Ledré, Charles La Presse à l'assaut de la monarchie. (1960). p.70.

- Marie Amélie, 356; (17 April 1827); Antonetti, 527.

- Duc de Dolberg, Castellan, II, 176 (letter 30 April 1827)

- Mansel, Philip, Paris Between Empires (St. Martin Press, New York 2001) p. 238

- Mansel, 2001, p.238

- Pinkey, 83–84; Rémusat, Mémoires II, 313–314; Lendré 107

- Pickney, David. The French Revolution of 1830 (Princeton 1972), p. 93.

- Mansel, Philip, Paris Between Empires, (St. Martin Press, New York 2001) p.239.

- Olivier, Juste, Paris en 1830, Journal (27 July 1830) p.244.

- Olivier, Juste, Paris en 1830, Journal (28 July 1830) p. 247.

- Mansel, Philip, Paris Between Empires (St. Martin Press, New York 2001) p.245.

- Mansel, Philip, Paris Between Empires (St. Martin Press, New York 2001) p.247.

- de Vigny, Alfred, Journal d'un poète, 33, (29 July 1830).

- Mémoires d'outre-tombe, III, 120; Fontaine II, 849 (letter of 9 August 1830).

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to French Revolution of 1830. |

- Berenson, Edward. Populist religion and left-wing politics in France, 1830–1852 (Princeton University Press, 2014).

- Collingham, Hugh AC, and Robert S. Alexander. The July monarchy: a political history of France, 1830–1848. Longman Publishing Group, 1988.

- Fortescue, William. France and 1848: The end of monarchy (Routledge, 2004).

- Hone, William (1830). Full Annals of the Revolution in France, 1830 ... Illustrated with engravings (Second ed.). London: Thomas Tegg.

- Howarth, T.E.B. Citizen King: Life of Louis-Philippe (1975).

- Lucas-Dubreton, Jean. The Restoration and the July Monarchy (1923) pp. 174–368.

- Newman, Edgar Leon, and Robert Lawrence Simpson. Historical Dictionary of France from the 1815 Restoration to the Second Empire (Greenwood Press, 1987) online edition

- Pilbeam, Pamela (June 1989). "The Economic Crisis of 1827–32 and the 1830 Revolution in Provincial France". The Historical Journal. 32 (2): 319–338. doi:10.1017/S0018246X00012176.

- Pilbeam, Pamela (December 1983). "The 'Three Glorious Days': The Revolution of 1830 in Provincial France". The Historical Journal. 26 (4): 831–844. doi:10.1017/S0018246X00012711.

- Pinkney, David H. (1961). "A New Look at the French Revolution of 1830". Review of Politics. 23 (4): 490–506. doi:10.1017/s003467050002307x. JSTOR 1405706.

- Pinkney, David H. (1973). The French Revolution of 1830. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691052021.

- Price, Roger (December 1974). "Legitimist Opposition to the Revolution of 1830 in the French Provinces". The Historical Journal. 17 (4): 755–778. doi:10.1017/S0018246X00007895.

- Rader, Daniel L. The Journalists and the July Revolution in France: The Role of the Political Press in the Overthrow of the Bourbon Restoration, 1827–1830 (Springer, 2013).

- Reid, Lauren. "Political Imagery of the 1830 Revolution and the July Monarchy." (2012).

Primary sources

- Collins, Irene, ed. Government and society in France, 1814–1848 (1971) pp. 88–176. Primary sources translated into English.

- Olchar E. Lindsann, ed. Liberté, Vol. II: 1827-1847 (2012) pp 105–36; ten original documents in English translation regarding July Revolution online free

In French and German

- Antonetti, Guy (2002). Louis-Philippe. Paris: Librairie Arthème Fayard. ISBN 2-213-59222-5.

- Schmidt-Funke, Julia A. (2011). "Die 1830er Revolution als europäisches Medienereignis". European History Online (in German). Institute of European History, Mainz. OCLC 704840169. Retrieved 21 February 2013.