Fortified position of Liège

The fortified position of Liège was established following World War I by Belgium to block the traditional invasion corridor from Germany through Belgium to France. The Belgian experience of World War I, in which the Belgian Army held up the invading force for a week at Liège, impeding the German timetable for the conquest of France, caused Belgium to consider a refined defence strategy. Belgium upgraded the existing fortifications of Liège and extended them onto the Herve plateau closer to Germany, using the most advanced fortifications available to Belgian military technology. However, in 1936, Belgium's neutrality was proclaimed by King Leopold III of Belgium in a vain attempt to forestall another conflict, preventing France from being able to make active use of the Belgian defences and territory in the forward defence of France. At the outbreak of World War II, Belgium's defences had to resist alone until France could advance into Belgium after neutrality failed. Again the fortifications could not hold the Germans.

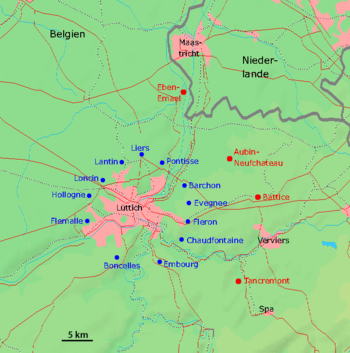

The position fortifiée de Liège (PFL) was divided into the modern defensive line, anchored on the Albert Canal by Fort Eben-Emael and extending to the south through a planned five additional forts, designated PFL I, and the ring of forts around Liège itself. Liège commanded crucial road and rail crossings of the Meuse, and remained as strategically important in the 1930s as in 1914. The modernized Liège forts were designated PFL II.

Background

With Belgium's independence in 1830 from the Netherlands, the former inherited a large amount of Napoleonic-era forts from the latter. Their integration into a new defensive strategy became part of a larger series of debates in the country that would last for decades. Strong anti-military civilian protests slowed the development a national defence strategy even during the revolutions of 1848.[1] Demolition of the legacy forts began in 1851 to save the money spent on their maintenance. That same year however Napoleon III dissolved the French National Assembly and formed the Second French Empire. Defense against an ascendant France was now the Belgian government's top priority. They adopted, also in 1851, a stratagem pioneered in 1847 by general Pierre Emmanuel Félix Chazal. The Belgian Army was to be concentrated at Antwerp, the National Redoubt, and the Meuse fortified at Namur and Liège. Six committees, meeting from 1847 to 1856 and advised by military officers and government officials, returned Chazal's judgement. His plan, now sanctioned, would remain unaltered for the rest of the century.[2]

Beginning in 1870 and ending the next year, the Franco–Prussian War had enormous geopolitical consequences. A now-united Germany in the German Empire had annexed Alsace-Lorraine from France and thus ensured another war between the two nations.[3] Belgium, itself almost pulled into the war, now had to turn its focus south. The new path for French or German soldiers into each other's nations was through the lightly defended Meuse river valley – through lightly defended southern Belgium and the unfortified French border. According to Chazal's doctrine, the forts of the Meuse were to be the fulcrum and crossing points for the army at Antwerp. At that moment, those fortresses numbered two: the citadels of Liège and Namur, which together controlled 18 out of 26 crossing over the Meuse.[4] Within Liège alone were seventeen roads with twelve bridges over the Meuse and three train stations linking seven rail lines. The heights near the city commanded not only the nearby Herve and Hesbaye plains, but a 16-kilometre (9.9 mi) gap between Liège and the Dutch border.[5] For over a decade following the Franco–Prussian War, several Belgian Ministers of War and even Otto von Bismarck urged the fortification of the Meuse. In 1882, Prime Minister Walthère Frère-Orban finally commissioned draft plans for fortresses to be built at Liège and Namur, and the strategically important crossings at Visé and Huy.[6]

The job was given to military engineer and architect Henri Alexis Brialmont, a long-term advocate of Chazal's doctrine and the builder of the National Redoubt. Already in 1882, Brialmont studied Belgium's military situation,[7] then published a treatise by that name (Situation Militaire de la Belgique).[5] Again political debate slowed the militarization of the Meuse until 31 December 1886, when Brialmont was invited conduct another study. He finished and presented his report on 15 January 1887, calling for a system of military installations around Liège and Namur similar to the one he built around Antwerp.[8] His plans were approved on 1 February 1887.[9] Yet again, funding was not secured because of political squabbling until June 1887,[10] when Brialmont was finally given a budget.[11]

Design and construction

The final traditional siege of a fortress in Europe took place at Antwerp in 1832, when French high-angle artillery ignored the bastions of the city's citadel and destroyed its interior area. Artillery continued to evolve until, in the 1870s, it became rifled. Artillery was now more powerful, more accurate, and could be used from greater distances. French tests with high-explosive melinite shells in 1886 at the Fort de la Malmaison showed increased effectiveness against masonry fortifications. Combined with delayed fuzes, the shells were able to explode underground, next to the fort's masonry and destroy it. Bastion forts – the tradition in European defences for a century – were now totally obsolete. In response to artillery's increased reach, military architects began in the 1850s to build detached polygonal forts farther away from cities to protect them from bombardment. To counter its new destructive power, architects began making those forts more durable.[12][13]

In 1887, French military engineer Henri-Louis-Philippe Mougin produced plans for a "fort of the future" (Fort de l'Avenir), calling for a mostly underground fortress built of concrete and armed with artillery in retractable steel gun turrets.[14] Concrete, invented early in the 19th century, was found to be much more resistant to new artillery shells. Following its use in the upgrading of the Séré de Rivières system in 1887,[15] concrete became the standard building material for fortresses. The success of ironclad warships in the Crimean War inspired the other innovations of Mougin's design: gun turrets and metal armour.[14] The initial strides in this field were made by Germans Hermann Gruson and Maximilian Schumann, but Frenchmen like Mougin himself perfected fort gun turrets and made them retractable using counterweights. The Swiss built a prototype of Mougin's fort at Airolo,[16] and the French as well at Froideterre, near Verdun.[14] Although Mougin's plan was never adopted by the French military, Brialmont was most likely familiar with it.[17]

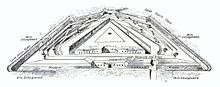

At Liège, 12 forts – six small and six large – were to be placed in a ring 7–9 kilometres (4.3–5.6 mi) from the city.[18] The circumference of the city's fortress ring was about 46 kilometres (29 mi), with a gap of around 3.8 kilometres (2.4 mi) between some of the forts,[19] held by intermediate works. The ring forts were placed away from ravines or depressions that could conceal attackers. There were also to be a fort at Visé to guard its ford over the Meuse and at Huy, half-way between Liège and Namur.[20] Construction of the Meuse forts was first estimated to cost 24 million francs,[18] and this was the sum given to Brialmont on 1 June 1887 even before his geological surveys were complete. To his consternation, no funds were allotted for Visé or Huy,[11][18] and Brialmont had to economize his plans for the forts he could build. There just two traces, a triangular or a trapezoidal shape, depending on the terrain. The fort structures were regimented similarly. There were three plans for the gorges and two for the central bunker, its casemates, and connecting galleries. The Meuse fortresses would be the first to be built entirely of concrete. The 'base' of a fort faced Liège, as did its entry ramp. During the Battle of Liège, the fortress ring was bolstered with the addition of 31 redoubts and 63 trenches, behind and in front of the forts and surrounded by barbed wire.[21]

The Belgian government opened contractor bidding in May 1888 and, on 1 July 1888, awarded the contract to the French firm Hallier, Letellier Brothers, and Jules Barratoux. Construction began on 28 July 1888 with the clearing and excavation of the sites and building of storage and work structures. Work was finished three years later, on 29 October 1891,[22] and cost a total of ₣71,600,000.[9][23] Around Liège, workers excavated 1,480,000 m3 (52,000,000 cu ft) of earth (100,000–175,000 m3 (3,500,000–6,200,000 cu ft) in the first 15 months), poured 601,140 m3 (21,229,000 cu ft) of concrete, and laid 12,720 m3 (449,000 cu ft) of brick.[24]

Protection

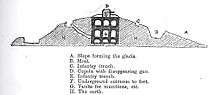

Brialmont designed the Meuse forts to withstand the power of the heaviest artillery of his day: 21-centimetre (8.3 in) pieces whose shells put out 240 metric tons (240 long tons; 260 short tons) of force. As a response to the 1886 melinite tests, he covered the masonry in the walls with a thick layer of concrete which itself was then covered with 3 metres (9.8 ft) of soil.[25] The mixtures of concrete used, of which there were two,[11][lower-alpha 1] were determined by testing at the Fort de Brasschaat.[15] Concrete was poured into wooden frames and left in place for over two weeks. Once dry, mortar would be brushed over the concrete until smoothed on the interior, and covered in soil on the exterior. The vulnerability of a structure determined the thickness of the concrete protecting it; the gorge wall of a barrack was 1.5 m (4.9 ft) thick, while the exposed top of the massif was 4 m (13 ft) thick. Protection against infantry was offered by a sea of barbed wire on the glacis around the ditch and the casemates of the gorge, housing 5.7 cm cannons and garrison infantry. These troops were also to be mustered in the massif for a sortie in case of a hostile infantry assault.[27]

The German siege artillery that engaged the Meuse forts in World War I generated an excess of 3,600 metric tons (3,500 long tons; 4,000 short tons) of force. Compounding the deficit between modern artillery and the Meuse forts was that concrete could not be poured at night because of a lack of illumination equipment.[28] Left to dry overnight, concrete poured the day before would not fully bond with the concrete of the next day. The consequences of this were severe. The explosion that annihilated the Fort de Loncin in August 1914 dislocated many different layers of concrete, resulting in immense damage to the entire fort.[29] Later French and German works inspired by the Meuse forts did not suffer the same issue because of proper equipment and illumination at night.[18] The relative thinness of the gorge front concrete would allow the Belgian Army to, in the event of a fort's capture, shell it from the city—from behind. The concrete and armour around the windows would be thus eroded until shells were exploding inside the barracks, forcing the garrison deeper within. The Imperial German Army, by entering Liège and Namur while attacking their forts, were able to do exactly this and to devastating effect.[30]

Armament

The Meuse forts were armed with a total of 171 gun turrets,[23][29] whose manufacture, transportation, and installation costed ₣24,210,775 in total.[23][lower-alpha 2] They were made of steel and placed in a concrete well in the massif or main redoubt. A turret itself sat on top a set of rollers, allowing it to turn 360°, and moved up and down its well with tracks running the length of the well. While smaller turrets could completely retract into the fortress, larger-calibre guns could not because of the length of their barrels. A steel collar protected the lip of the turret well and prevented the displacement of the turret in case the nearby concrete was damaged.[31] In October 1912, a cycle of artillery tests held in Russia and attended by Belgian officials showed this not to be the case. 15 cm shells could jam the turret in place, while 28 cm shells could entirely dislodge them from battery.[19]

The turret and therefore the guns within were moved, aimed, and fired from within the turret. This was done either by an observer within the gun directly, or indirectly with the use of a graduated ring that showed 1/20ths of a degree. According to Brialmont's specifications, a gun turret could make a complete rotation in 1.5 minutes, and three rotations in five minutes. Once the right angle and elevation was found, a brake was engaged to hold the turret in place. Ordinance was hoisted in a basket with a manual elevator to the gun, which was fitted with a hydraulic recoil brake containing 80% glycerine and 20% water. The turret was kept under negative pressure using a manual ventilator to expel fumes from the gun and to keep fumes from incoming shells out of the fort. In case of a malfunction, a gun could be removed and replaced within a few hours. Munitions were held beneath the turrets in separate form and without cartridge casings for larger-calibre guns and in a complete shell for 5.7 cm guns. Every one of the Meuse forts' guns used black powder and were never modified to use a smokeless alternative.[32]

The smallest artillery employed in the Meuse forts was the 5.7-centimetre (2.2 in) Nordenfelt cannon, used to evaporate attacking infantry at close range. These were usually mounted on a wheeled triangular carriage but sometimes in turret form. In large forts, there were nine 5.7 cm guns in casemates – two in each gorge casemate, four in the head casemate, and one in the casemate guarding the entry ramp. In small forts, there were also nine 5.7 cm guns. Four were placed in gorge ditch casemates near the entrance, while another defended the ramp. Trapezoidal forts of either size had two of their nine 5.7 cm guns in the casemaste defending the fourth angle of the fort. Large forts had four 5.7 cm turrets, while small forts had three. These all contained a singe gun, crewed by six men, and exclusively fired grapeshot. The casemate guns were produced by Cockerill and Krupp, while the turret versions were manufactured by Gruson.[33]

The rest of a fort's arsenal was contained in turrets and the makeup of a fort's armament depended on its size. Large forts received a single 15 cm turret sporting two guns, two two-gun 12 cm turrets, and two one-gun 21 cm turrets. Small forts had two one-gun 12 cm turrets and a one-gun 21 cm turret. These were produced by Gruson, Creusot, Saint-Chamond, Ateliers de la Meuse, and Chatillon-Commentry. Additional guns were supplied by Marcinelle-Couillet, but only at the Fort de Boncelles and the large forts at Namur, and by Vanderkerhove, unique to Liège's large forts. All of the forts possessed a 60 cm searchlight in a turret produced by Ateliers de la Meuse.[34]

Garrison and utilities

The Meuse forts were garrisoned by a mix of infantry, artillerymen, engineers, and support staff. During peacetime, they lived in temporary wooden barracks on the surface that were to be dismantled or burned if war broke out. During hostilities the garrison moved into the gorge caserne, eight to twelve men to a room. Power was supplied by a steam engine apparatus in the lower levels of a fort's massif, although petrol lamps lit most of a fort. About 80 t (79 long tons; 88 short tons) of coal and 3,500 l (770 imp gal; 920 US gal) of petroleum were stored within a fort. The primary means of communication between the forts were above telegraph or telephone fires operated by civilians. Latrines were poorly planned and ventilation nonexistent, except at the Fort de Loncin. The drainage system was also poorly designed. Water was pulled from underground wells or collected during and after rains in a cistern to be used by the fort. During the Battle of Liège, shell fire created debris that blocked the water pipes to the engine room, or flooded the munitions rooms and living areas.[35]

World War I

%2C_page_143_-_BL.jpg)

War came in 1914, and Liège became the early focus of German attack on the way to France. The forts were known to have shortcomings in their ability to resist heavy artillery, and had never been modernised.[36] During the Battle of Liège the forts were pounded by heavy German artillery of 21 cm, 28 cm and 42 cm. The forts had never been designed to resist such heavy artillery. The bombardment exposed the forts' shortcomings in living arrangements, sanitation, ventilation, construction and protection, culminating with the explosion of the Fort de Loncin under bombardment. Even before this the forts had begun to surrender one by one as they became uninhabitable and unable to respond to attack. German forces defeated the troops assigned to defend the intervals between forts, penetrating to Liège and taking it before the first fort had surrendered.[37]

The forts' mission was to delay the progress of an enemy for the time required for the Belgian Army to mobilise. Left to themselves, the forts were planned to resist a siege for about a month, based on estimates made in 1888. In 1914 the forts were completely outclassed by the much more powerful German artillery, which included the enormous Big Bertha 42 cm howitzer. It was therefore a surprise that the forts resisted as long and as successfully as they did. However, the forts' poor ability to deal with powder gases, pulverized dust and the stench from inadequate sanitary facilities became a determining factor in the endurance of the forts' garrisons. None of the forts, apart from the Fort de Loncin, possessed forced ventilation.[38]

The Belgian forts made little provision for the daily needs of their wartime garrisons, locating latrines, showers, kitchens and the morgue in the fort's counterscarp, a location that would be untenable in combat. This had profound effects on the forts' ability to endure a long assault. These service areas were placed directly opposite the barracks, which opened into the ditch in the rear of the fort (i.e. in the face towards Liège), with lesser protection than the two "salient" sides. This arrangement was calculated to place a weaker side to the rear to allow for recapture by Belgian forces from the rear, and in an age where mechanical ventilation was in its infancy, allowed natural ventilation of living quarters and support areas. However, the concept proved disastrous in practice. Heavy shellfire made the rear ditch untenable, and German forces were able to get between the forts and attack them from the rear. The massive German bombardments drove men into the central massif, where there were insufficient sanitary facilities for 500 men, rendering the air unbreathable, while the German artillery destroyed the forts from above and from the rear.[39]

Battle of Liège

In the Battle of Liège the Liège fortifications fulfilled their role, stopping the German army long enough to allow the Belgian and French armies to mobilize. The battle revealed shortcomings in the performance of the forts and in the Belgian strategy. The forts themselves suffered from inherent weakness of construction through poor understanding of concrete technology, as well as overall inadequate protection for the garrison and ammunition stores from heavy-caliber artillery bombardment. Unbreathable air from bombardment, the fort's own gun gases and from human waste compelled the surrender of most of the positions. However, the days-long delay caused by the fortress ring allowed the Belgian, and more importantly, the French armies to complete their mobilizations. Had the Germans captured Liège as they had hoped, by a bold stroke, the German army could have been in Paris before France could organize its defence at the First Battle of the Marne.[40]

Position Fortifiée de Liège (PFL)

The Fortified Position of Liège was conceived by a commission charged with recommending options for the rebuilding of Belgium's defences. The 1927 report recommended the construction of a line of new fortifications to the east of the Meuse. Work was seriously delayed by budget crises, forcing work on all fortifications but Eben-Emael to be delayed. Work finally began on the forts at Battice, Aubin-Neufchâteau and Tancrémont in 1933. Two other planned positions were never pursued, with Aubin-Neufchâteau taking over the role of forts planned at Mauhin and Les Waides.[41] There were five layers to the system:

- Positions avancées: 66 small bunkers positioned close to the border as a delaying position.

- PFL I: Four modern forts supported by 178 bunkers.

- PFL II: The southern and eastern portions of the Brialmont fortress ring around Liège, modernized and provided with interval bunkers and anti-tank obstacles. There were 62 infantry shelters and 6 forts in this section.

- PFL III: Small fortifications defending three crossings of the Meuse, comprising 42 bunkers on the eastern side of the river.

- PFL IV: Three layers of defences on the west side of the Meuse, comprising a line on the Meuse with 31 bunkers, a line on the Albert Canal with nine bunkers, and ten bunkers with the Forts de Pontisse and Flémalle.[42]

PFL II

The Belgians initially rebuilt eight forts of the ring to the south and east of Liège, with later work on the west side of the fortress ring. It was not possible to repair the Fort de Loncin, which had been completely destroyed by its own magazines in 1914. The improvements addressed the shortcomings revealed by the Battle of Liège, allowing the fortress ring to be a backstop to the primary line of fortifications farther east. The Liège ring was designated PFL II,[43] although the forts on the west side of the river were part of PFL IV.[42]

Improvements included replacing 21 cm howitzers with longer-range 15 cm guns, 150mm howitzers with 120mm guns, and adding machine guns. Generating plants, ventilation, sanitation and troop accommodations were improved, as well as communications. The work incorporated alterations that had already been made by the Germans during their occupation of the forts in World War I. Most notably, the upgraded forts received defended air intake towers, intended to look like water towers, that could function as observation posts and emergency exits.[43]

PFL I

Four new forts were built about 20 kilometres (12 mi) to the east of Liège, of a planned six. In contrast to the ring of forts protecting Liège, the new fortification line was similar in concept to the French Maginot Line: a series of positions in a line along the frontier, intended to prevent an enemy advance into Belgian territory, rather than to defend a specific strong point.[44][45] This new line was designated PFL I, the primary defence line against an advance from Germany, as well as a German advance through Dutch territory at Maastricht. Fort Eben-Emael was positioned to defend the water obstacle of the Albert Canal and to anchor the northern end of the line, with a field of fire all the way north to Maastricht. The Fort de Battice occupied the second strategic point on the main road and rail lines from Aachen. The forts de Tancrémont and Aubin-Neufchâteau filled in the intervals. The cancelled Fort de Sougné-Remouchamps was to be similar to the smaller forts, while plans for two small forts at Comblain-du-Pont and Les Waides were abandoned early in the planning process. The big forts had as many as 2000 men, the smaller 600.[46]

While the organization of the overall defensive line mimicked the Maginot Line, the design of the individual forts was conservative. In contrast to the French fortifications, distributed along a single main gallery in the fort palmé concept, the Belgian forts remained a set of powerfully-armed, tightly grouped combat blocks surrounded by a defended ditch. Eben-Emael and Battice featured 120mm gun turrets with a range of 18 kilometres (11 mi), and all four forts were equipped with 75mm gun turrets (10 kilometres (6.2 mi)) and French 81mm mortars in pit emplacements.[47] Eben-Emael, with its site along the artificial cliff of the Albert Canal cutting, was the only fort to be equipped with artillery casemates. The sheer face also provided a naturally-defended location for the fort's air intakes. The new forts featured extreme levels of concrete and armour protection, with between 3.5 metres (11 ft) and 4.5 metres (15 ft) of concrete cover and up to 450 millimetres (18 in) of armour on turrets. Learning from World War I, the intervals between forts were liberally supplied with observation positions and infantry shelters.[48]

Second World War battles

The Belgian command was counting on Eben-Emael to be the key defense of the northern frontier at Liège. It naturally attracted the first German attacks. Its enormous dimensions dictated an unconventional attack strategy, using airborne troops. The fort was attacked on 10 May 1940 and rendered ineffective in a few hours by a team of 75 men armed with new shaped-charge explosives. Ineffective Belgian defense of the fort's surface allowed the German assault team to use their explosive charges to destroy or render the fort's gun turrets and machine gun cloches uninhabitable.[49]

With Eben-Emael out of action, the Germans could attack the other new forts with more conventional means, continuing attacks from 10 May. The forts of both PFL I and II attempted to support each other with covering fire, but to little effect. The PFL I forts quickly fell, with Battice and Aubin-Neufchâteau surrendering on 22 May. Tancrémont was bypassed.[50]

The PFL II forts were assaulted starting 12 May after Belgian field forces retreated from Liège. Isolated, the forts fought on. Fort de Flémalle came under air attack on 15 May, surrendering the next day. On 18 May Fort de Barchon was assaulted by the same infantry battalion that had attacked Eben-Emael, supported by a 420mm howitzer. The fort surrendered the same day, as did Fléron and Pontisse. Evengnée surrendered on 20 May. The other forts to the south were bypassed and surrendered on 28 May, part of the general Belgian surrender. Tancrémont held out until the next day, the last fort to surrender.[49]

During the Second World War Eben-Emael was abandoned, apart from use for propaganda films and weapons effects experiments, including armor-piercing shells. Battice and Aubin-Neufchâteau were also used for these experiments.

Present day

Of the dozen Brialmont forts, seven are open to the public and may be visited – Loncin, Lantin, Flémalle, Hollogne, Pontisse, Barchon and Embourg. Chaudfontaine may also be visited under certain circumstances, but has not been rehabilitated. The Fort de Loncin has since the explosion of 15 August 1914, been a military cemetery and memorial. The Fort de Lantin has been extensively restored, and since it was not re-armed between the wars, it presents the appearance of an 1888 fort.[51]

Other forts have been partially buried (Fléron, Boncelles) and are not visitable, apart from the air intake tower of Boncelles. Others are supply depots for the Belgian Army.[51]

The four inter-war forts are in varying states of preservation, though all may be visited. Tancrémont is notably intact, with all equipment present.[51][52] Eben-Emael and the others remain military property, but Eben-Emael is administered by the Association Fort Eben-Emael as a museum.[53]

See also

- Fortified Position of Namur

- National redoubt of Belgium, Antwerp

- Battle of Liège

- Battle of Belgium

Notes

- The first was for the foundations, and the second was for the masonry walls and vaulting. Both were mixed on-site from Portland cement, 300,000 metric tons (300,000 long tons; 330,000 short tons) of which was produced in Belgium and France, and locally sourced gravel and sand, dredged from the Meuse.[26]

- Gruson, a German firm, had offered ₣17,409,378 to be the sole supplier for the Meuse forts, but the Belgian government was pressured by French and Belgian firms into splitting the contract. This was done to allow the Belgian companies access to the technology of their French and German counterparts.[23]

Citations

- Draper 2018, pp. 157–58.

- Draper 2018, pp. 158, 160–61, 163, 165.

- Varley 2008, pp. 62–80.

- Draper 2018, pp. 167–69, 172, 175.

- Donnell 2007, p. 8.

- Draper 2018, pp. 169–70.

- Draper 2018, pp. 166–67, 170.

- Draper 2018, pp. 171–72.

- Donnell 2007, p. 6.

- Draper 2018, pp. 172, 173–175.

- Donnell 2007, p. 9.

- Donnell 2007, pp. 4–5.

- Donnell 2013, pp. 7, 8.

- Donnell 2007, p. 5.

- Donnell 2013, p. 8.

- Donnell 2013, p. 10.

- Donnell 2013, p. 12.

- Draper 2018, p. 172.

- Kaufmann & Kaufmann 2014, p. 89.

- Donnell 2007, pp. 30, 32, 35.

- Donnell 2007, pp. 5, 9, 21, 33.

- Donnell 2007, pp. 6, 9, 12.

- Draper 2018, p. 173.

- Donnell 2007, p. 9, 10, 12.

- Draper 2018, pp. 172–73.

- Donnell 2007, pp. 9, 12.

- Donnell 2007, pp. 9, 12–13, 35, 36.

- Draper 2018, pp. 172, 173.

- Donnell 2007, p. 13.

- Donnell 2007, p. 36.

- Donnell 2007, pp. 14–15.

- Donnell 2007, pp. 14–15, 16–17.

- Donnell 2007, pp. 13, 16, 35.

- Donnell 2007, pp. 16, 17.

- Donnell 2007, p. 17, 19–20, 36.

- Dunstan 2005, p. 4.

- Donnell 2007, pp. 19, 36, 49, 52–53.

- Donnell 2007, pp. 6, 17, 18.

- Donnell 2007, pp. 32, 26, 52–53.

- Donnell 2007, pp. 52–54.

- Dunstan 2005, pp. 11–12.

- Bloock 2005.

- Kaufmann & Jurga 2002, p. 100.

- Kaufmann & Jurga 2002, p. 103.

- Dunstan 2005, pp. 10–12.

- Kaufmann & Jurga 2002, p. 109.

- Kaufmann & Jurga 2002, p. 114.

- Kaufmann & Jurga 2002, pp. 108–110.

- Kaufmann & Jurga 2002, pp. 115–116.

- Kaufmann & Jurga 2002, pp. 116–117.

- Donnell 2007, pp. 57–61.

- "Nouveaux forts". P.F.L. (in French). Centre Liègeois d'Histoire et d'Archéologie Militaire. Archived from the original on 11 March 2012. Retrieved 26 October 2010.

- Dunstan 2005, p. 60.

References

- Bloock, Bernard Vanden (2005). "Border Defences". Belgian Fortifications, May 1940. orbat.com. Archived from the original on 19 January 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Draper, Mario (2018). The Belgian Army and Society from Independence to the Great War. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9783319703862.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Donnell, Clayton (2007). The Forts of the Meuse in World War I. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84603-114-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Donnell, Clayton (2013). Breaking the Fortress Line 1914. Pen and Sword. ISBN 9781473830127.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dunstan, Simon (2005). Fort Eben Emael. The key to Hitler's victory in the West. Illustrated by Hugh Johnson. Osprey. ISBN 978-1841768212.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kaufmann, J.E.; Kaufmann, H.W. (2014). The Forts and Fortifications of Europe 1815–1945: The Neutral States: The Netherlands, Belgium and Switzerland. Pen and Sword. ISBN 9781783463923.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kaufmann, J E; Jurga, Robert M (2002). Fortress Europe: European Fortifications of World War II. Da Capo. ISBN 978-0306811746.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Romanych, Marc; Rupp, Martin (2013). 42cm "Big Bertha" and German Siege Artillery of World War I. Illustrated by Henry Morshead. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78096-017-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Varley, Karine (2008). "The Taboos of Defeat: Unmentionable Memories of the Franco-Prussian War in France, 1870–1914". In Macleod, Jenny (ed.). Defeat and Memory: Cultural Histories of Military Defeat in the Modern Era. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-51740-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Kaufmann, J.E.; Donnell, Clayton (2004). Modern European Military Fortifications, 1870–1950: A Selective Annotated Bibliography. Greenwood Publishing. ISBN 9780313316470.

External links

- Centre Liégeois d’Histoire et d’Archéologie Militaire (in French)

- Indexe des Fortifications Belges at fortiff.be (in French)

- Fort Eben-Emael "Fortissimus" site

- Fort de Tancrémont (in French)