Fort de Boncelles

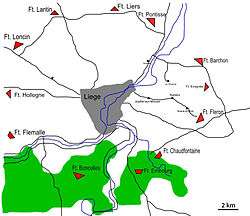

The Fort de Boncelles is one of twelve forts built as part of the Fortifications of Liège in the late 19th century in Belgium. It was built between 1881 and 1884 according to the plans of General Henri Alexis Brialmont. Contrasting with the French forts built in the same era by Raymond Adolphe Séré de Rivières, the fort was built exclusively of unreinforced concrete, a new material, rather than masonry. The fort was heavily bombarded by German artillery in the Battle of Liège. Boncelles was upgraded in the 1930s to become part of the fortified position of Liège in an attempt to forestall or slow an attack from Germany. It saw action in 1940 during the Battle of Belgium, and was captured by German forces. It is abandoned and partly buried, surrounded by housing.

| Fort de Boncelles | |

|---|---|

| Part of Fortifications of Liège | |

| Seraing, Belgium | |

Air intake tower | |

Fort de Boncelles | |

| Coordinates | 50.5791°N 5.52869°E |

| Type | Fort |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by | Belgium |

| Open to the public | No |

| Condition | Abandoned, partly buried |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1881 |

| Materials | Unreinforced concrete |

| Battles/wars | Battle of Liège, Battle of Belgium |

Description

The Fort de Boncelles is located about 8.3 kilometres (5.2 mi) south of the center of Liège.

The fort forms an isosceles triangle whose base is 300 metres (980 ft) long and whose sides measure 235 metres (771 ft). A 6-metre (20 ft) deep by 8-metre (26 ft) ditch encircles the fort. The principal armament was concentrated in the central massif. The ditches were defended in enfilade by 57mm guns in casemates resembling counterscarp batteries, firing at shot traps at the other end of the ditch.[1] It is one of the larger forts of Liège.

With the exception of the Fort de Loncin, the Belgian forts made little provision for the daily needs of their wartime garrisons, locating latrines, showers, kitchens and the morgue in the fort's counterscarp, a location that would be untenable in combat. This would have profound effects on the forts' ability to endure a long assault. The service areas were placed directly opposite the barracks, which opened into the ditch in the rear of the fort (i.e., in the face towards Liège), with lesser protection than the two "salient" sides.[1] The Brialmont forts placed a weaker side to the rear to allow for recapture by Belgian forces from the rear, and located the barracks and support facilities on this side, using the rear ditch for light and ventilation of living spaces. In combat heavy shellfire made the rear ditch untenable, and German forces were able to get between the forts and attack them from the rear.[2]

The Brialmont forts were designed to be protected from shellfire equaling their heaviest guns: 21 cm.[3] The top of the central massif used 4 metres (13 ft) of unreinforced concrete, while the caserne walls, judged to be less exposed, used 1.5 metres (4.9 ft).[4] Under fire, the forts were damaged by 21 cm fire and could not withstand heavier artillery.[5]

Armament

Boncelles' armament included a two rotating Grüsonwerke turrets with two 21 cm guns, a15cm Creusot turret with twin guns and two 12 cm Châtillon-Commentry turret with two guns, all for distant targets. Four retractable 57 mm Grüsonwerke gun turrets were provided for local defense. The fort also mounted an observation turret with a searchlight. Eight rapid-fire 57 mm Grüsonwerke guns were provided in casemates for the defense of the ditches and the postern, as well as two mobile guns.[6]

The fort's heavy guns were German, typically Krupp, while the turret mechanisms were from a variety of sources. The fort was provided with signal lights to permit communication with the neighboring Fort de Flémalle across the Meuse and Fort d'Embourg across the Ourthe. The guns were fired using black powder rather than smokeless powder, producing choking gas in the confined firing spaces that spread throughout the fort.[7]

First World War

Boncelles first came under attack on 6 August 1914. Because the Liège fortifications had proved to be unexpectedly stubborn, the Germans brought heavy siege artillery to bombard the forts with shells far larger than they were designed to resist. Boncelles resisted until the 14th, when it was unable to continue to resist due to the asphyxiating fumes that permeated the fort.[8]

In 1915 the Germans undertook an improvement program for the Liège positions, modifying entrances, adding concrete cover and adding metal decking under concrete ceilings. Non-structural improvements included forced ventilation and moving latrines, kitchens and the bakery into the main fort.[6]

Fortified Position of Liège

Boncelle's armament was upgraded in the 1930s to become part of the Fortified Position of Liège II, which was planned to deter a German incursion over the nearby border.[9][10] Protection was substantially increased. This was accompanied by improvements to ventilation, protection, sanitary facilities, communications and electrical power. A fortified air intake tower was provided to improve ventilation.[11]

Second World War

The fort was bombarded from the air and by artillery in May 1940 by the Germans, killing the commandant, Numa Charlier, and others of the garrison. The fort was taken on May 16: it did not surrender.[12][13] The Germans occupied the fort until 1944, using it as an anti-aircraft position. It became a military depot after the war, and was sold to the commune of Seraing in 1983.[14][13]

Present

The fort is mostly buried and inaccessible, tightly hemmed in by housing that follows the trace of the former ditch. Only the postern, central massif, air intake tower and two nearby bunkers remain. The site includes a memorial to the dead of World Wars I and II, and a small cemetery.[14][15][13] A museum opened next to the fort at the end of 2012.[16]

References

- Donnell, Clayton (2007). The Forts of the Meuse in World War I. Osprey. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-84603-114-4.

- Donnell, p. 36

- Donnell, p. 52

- Donnell, p. 12

- Donnell, pp. 45-48

- Puelinckx, Jean. "Boncelles (fort de)". Index des fortifications belges (in French). fortiff.be.

- Donnell, p. 17

- Donnell, pp. 45-49

- Donnell, pp. 55-56

- Kauffmann, p. 105

- Puelinckx, Jean. "Barchon entre deux guerres". Index des fortifications belges (in French). fortiff.be.

- Puelinckx, Jean. "Mai 1940 à Pontisse". Index des fortifications belges (in French). fortiff.be.

- Donnell, p. 61

- Puelinckx, Jean. "Barchon (Historique de)". Index des fortifications belges (in French). fortiff.be.

- Puelinckx, Jean. "Barchon (fort de)". Index des fortifications belges (in French). fortiff.be.

- "Le Fort de Boncelles". Cite de Seraing. Archived from the original on 3 July 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

Bibliography

- Donnell, Clayton, The Forts of the Meuse in World War I, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, 2007, ISBN 978-1-84603-114-4.

- Kauffmann, J.E., Jurga, R., Fortress Europe: European Fortifications of World War II, Da Capo Press, USA, 2002, ISBN 0-306-81174-X.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fort de Boncelles. |

- La Tour d'Air, museum scheduled to open at the end of 2012 (in French)

- Fort de Boncelles at fortiff.be (in French)